Research on the Impact of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Engagement Behaviors in Virtual Brand Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Intercustomer Social Support and CEBs

2.2. Mediation of Self-Efficacy

2.3. Moderation of Interdependent Self-Construal

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Common Method Bias

4. Results

4.1. Measurement of Model

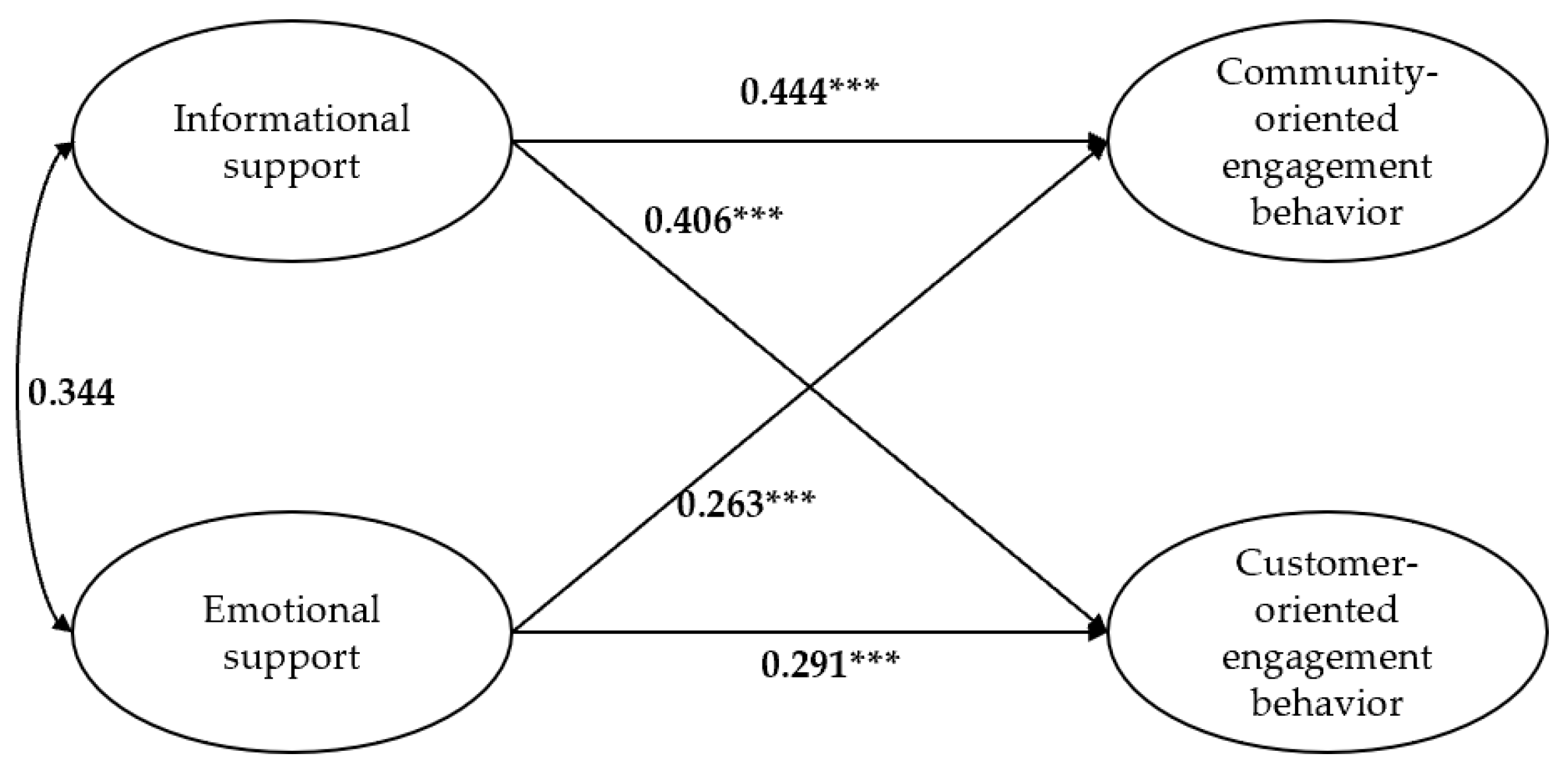

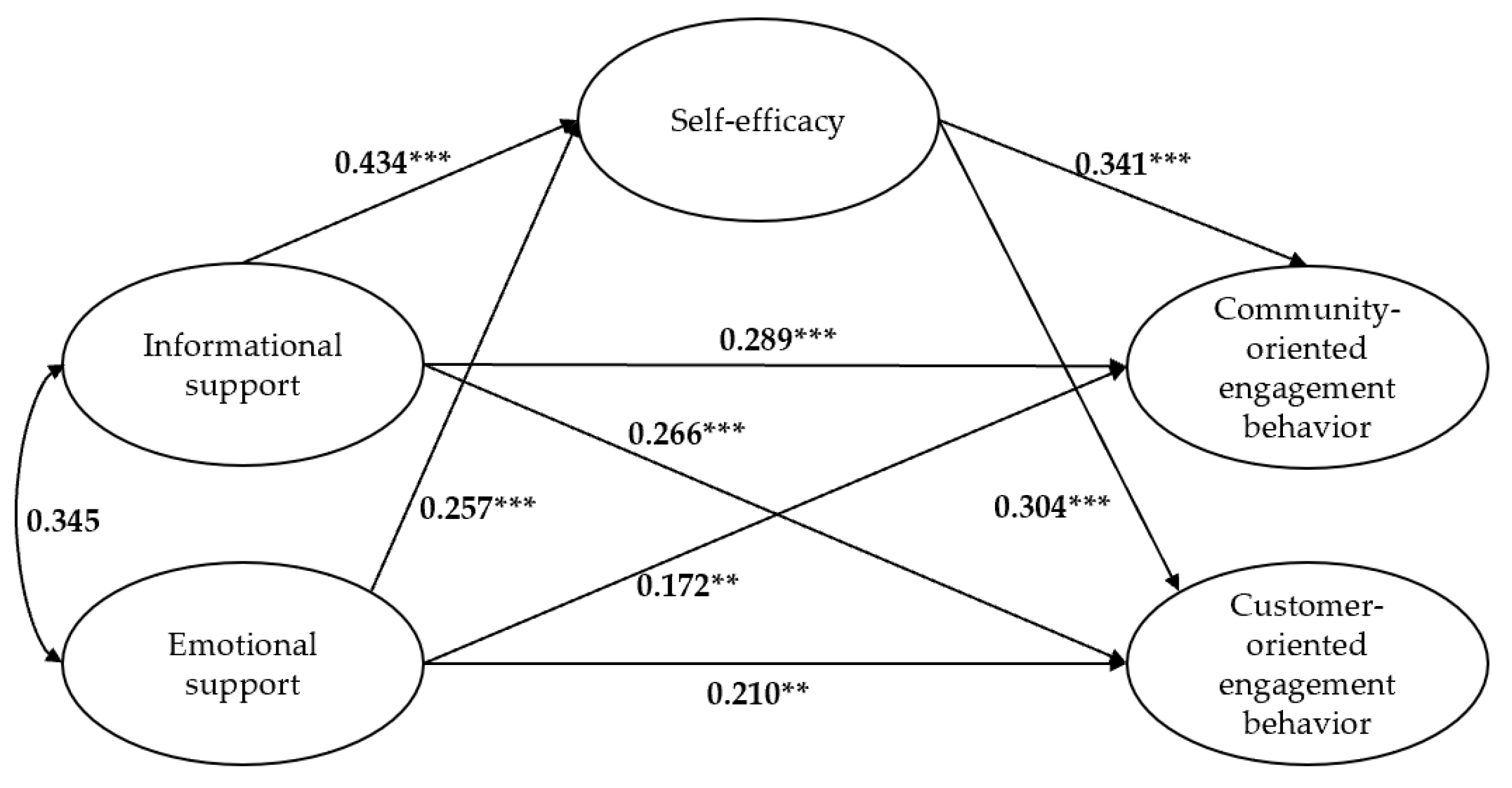

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Part I:

| Questionnaire Description |

| A virtual brand community is a virtual platform for users to interact and communicate around a certain brand on the network. Including but not limited to official forums such as Xiaomi Community, Club of Huawei, VIVO Community, OPPO Community, Lenovo Community, Weifeng Network, Club Canon, Lancome Community, as well as official Weibo, WeChat official account, and so on established around a certain brand. |

- Part II: Academic Scale

- (1) Indicate the extent to which you agree/disagree with the following statements.

| Strongly Disagree | Neutral | Strongly Agree | ||

| 1 | In the community, some customers would offer suggestions when I needed help. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 2 | In the community, some customers gave me information to help me overcome the problem. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 3 | In the community, some customers helped me discover the course and provided me with suggestions to solve the problem. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 4 | In the community, some customers told me the way to solve the problem. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 5 | When I am faced with difficulties, some customers on the community are on my side with me. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 6 | When I am faced with difficulties, some customers on the community comforted and encouraged me. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 7 | When I am faced with difficulties, some customers on the community listened to me talk about my private feelings. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 8 | Some customers on the community expressed interest and concern in my well-being. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

- (2) Indicate the extent to which you agree/disagree with the following statements.

| Strongly Disagree | Neutral | Strongly Agree | ||

| 9 | In order to receive the service smoothly, I do some necessary things. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 10 | In order to receive the service smoothly, I do what the brand community requires. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 11 | In order to receive the service smoothly, I do what the brand community expects of me. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 12 | I usually cooperate with the brand community workers. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 13 | If the brand’s community staff makes a mistake, I will give feedback. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 14 | I provide constructive suggestions to the brand community to improve its services. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 15 | I recommend the brand community to people interested in the brand. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 16 | I recommend this brand community to my family and friends. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 17 | I promote the positive aspects of the brand community to others. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 18 | I help other customers understand the brand better. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 19 | I help other customer if necessary. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 20 | I explain to other customers which services are provided by the brand community. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

- (3) Indicate the extent to which you agree/disagree with the following statements.

| Strongly Disagree | Neutral | Strongly Agree | ||

| 21 | I have the confidence to use the various functions of the community in the absence of guidance. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 22 | I am confident that I can provide valuable knowledge. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 23 | I have the necessary skills, experience, and insights to provide valuable knowledge. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 24 | I have the confidence to respond or comment on the information and articles from other members of the community. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

- (4) Indicate the extent to which you agree/disagree with the following statements.

| Strongly Disagree | Neutral | Strongly Agree | ||

| 25 | My happiness depends on the happiness of my fellows in this community. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 26 | I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of the group I am in. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 27 | It is important for me to maintain harmony with members of the community. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 28 | I often have the feeling that my relationships with others are more important than my own accomplishments. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

| 29 | It is important to me to respect decisions made by the group in the community. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | ||

- Part III: Basic Personal Information

- 1. Gender

- □ Men □ Women

- 2. Age

- □ Under 20 □ 21–30 □ 31–40 □ Over 41

- 3. Educational level

- □ High school/technical secondary school and below

- □ Associated degrees

- □ Undergraduate degrees

- □ Postgraduate degrees

- 4. Occupation

- □ Civil servant □ Company manager □ Ordinary employees of the enterprise

- □ Student □ Freelancer □ Retired □ Others

- Thank you for completing this survey.

References

- Muniz, A.M.; O’Guinn, T.C. Brand Community. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 27, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Valck, K.; van Bruggen, G.H.; Wierenga, B. Virtual Communities: A Marketing Perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 47, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Ilic, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Liu, R.J.; Zhong, X.J.; Zhang, R. Web of Science-Based Virtual Brand Communities: A Bibliometric Review between 2000 and 2020. Internet Res. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.-H.; Cheng, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Hong, X.-C. Does Social Perception Data Express the Spatio-Temporal Pattern of Perceived Urban Noise? A Case Study Based on 3137 Noise Complaints in Fuzhou, China. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 201, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Fu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Zheng, W. Impact of Power on Uneven Development: Evaluating Built-up Area Changes in Chengdu Based on Npp-Viirs Images (2015–2019). Land 2022, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.; Stavros, C.; Dobele, A.R. The Levers of Engagement: An Exploration of Governance in an Online Brand Community. J. Brand Manag. 2019, 26, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tong, D.; Huang, J.; Zheng, W.; Kong, M.; Zhou, G. What Matters in the E-Commerce Era? Modelling and Mapping Shop Rents in Guangzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 123, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Paruthi, M.; Islam, J.; Hollebeek, L.D. The Role of Brand Community Identification and Reward on Consumer Brand Engagement and Brand Loyalty in Virtual Brand Communities. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 46, 10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Baron, R.A. Interactions in Virtual Customer Environments: Implications for Product Support and Customer Relationship Management. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Rahman, M.; Voola, R.; De Vries, N. Customer Engagement Behaviours in Social Media: Capturing Innovation Opportunities. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Lin, X.; Wei, H. How Does Online Brand Community Value Influence Consumer’s Continuous Participation? The Moderating Role of Brand Knowledge. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2019, 22, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.G.; Ma, S.; Li, D.H. Customer Participation in Virtual Brand Communities: The Self-Construal Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.E.; Donthu, N.; MacElroy, W.H.; Wydra, D. How to Foster and Sustain Engagement in Virtual Communities. Calif Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 80–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, A.G.; Diop, P.A. Impact Drivers of Customer Brand Engagement and Value Co-Creation in China: A Prioritization Approach. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2017, 3, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verleye, K.; Gemmel, P.; Rangarajan, D. Managing Engagement Behaviors in a Network of Customers and Stakeholders: Evidence from the Nursing Home Sector. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Sotheara, H.; Virak, M. The Values of Virtual Brand Community Engagement of Facebook Brand Page. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2017, 3, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Sotheara, H.; Virak, M. Virtual Community Engagement on Facebook Brand Page. J. Int. Bus. Res. Mark. 2016, 2, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.; Yan, G. Analyzing Intention to Purchase Brand Extension Via Brand Attribute Associations Mediating and Moderating Role of Emotional Consumer-Brand Relationship and Brand Commitment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, A.L.; Parasuraman, A.; Bowen, D.E.; Patricio, L.; Voss, C.A. Service Research Priorities in a Rapidly Changing Context. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Shekhar, V.; Lassar, W.M.; Chen, T. Customer Engagement Behaviors: The Role of Service Convenience, Fairness and Quality. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.H.; Sun, H.; Chang, Y.P. Effect of Social Support on Customer Satisfaction and Citizenship Behavior in Online Brand Communities: The Moderating Role of Support Source. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2004, 47, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Black, H.G.; Vincent, L.H.; Skinner, S.J. Customers Helping Customers: Payoffs for Linking Customers. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Shervani, T.A.; Fahey, L. Market-Based Assets and Shareholder Value: A Framework for Analysis. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, R.; Catalan, S.; Pina, J.M. Intergenerational Differences in Customer Engagement Behaviours: An Analysis of Social Tourism Websites. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, M.; So, J. Influence of Social Identity on Self-Efficacy Beliefs through Perceived Social Support: A Social Identity Theory Perspective. Commun. Stud. 2016, 67, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyorat, K.; Alden, D.L. Self-Construal and Need-for-Cognition Effects on Brand Attitudes and Purchase Intentions in Response to Comparative Advertising in Thailand and the United States. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.K. The Role of Self-Construal in Consumers’ Electronic Word of Mouth (Ewom) in Social Networking Sites: A Social Cognitive Approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.F.; Dwyer, P.C.; Fuglestad, P.; Kim, J.; Maki, A.; Snyder, M.; Terveen, L. Encouraging Online Engagement: The Role of Interdependent Self-Construal and Social Motives in Fostering Online Participation. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018, 133, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Hardin, E.E.; Gercek-Swing, B. The What, How, Why, and Where of Self-Construal. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 142–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.; Goode, S.; Hart, D. Individualist and Collectivist Factors Affecting Online Repurchase Intentions. Internet Res. 2010, 20, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H.; Kaufman, G. Self-Construal, Social Support, and Loneliness in Japan. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.Y.; Huang, S.-C.; Mair, J. A Transformative Service View on the Effects of Festivalscapes on Local Residents’ Subjective Well-Being. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumaker, S.A.; Brownell, A. Toward a Theory of Social Support: Closing Conceptual Gaps. J. Soc. Issues 1984, 40, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doha, A.; Elnahla, N.; McShane, L. Social Commerce as Social Networking. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Anaya-Sanchez, R.; Liebana-Cabanillas, F. Analyzing the Effect of Social Support and Community Factors on Customer Engagement and Its Impact on Loyalty Behaviors toward Social Commerce Websites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 105980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Massiah, C.A. When Customers Receive Support from Other Customers—Exploring the Influence of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Voluntary Performance. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 9, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, N.S.; Buchanan, H.; Aubeeluck, A. Social Support in Cyberspace: A Content Analysis of Communication within a Huntington’s Disease Online Support Group. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 68, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.P.; Ho, Y.T.; Li, Y.W.; Turban, E. What Drives Social Commerce: The Role of Social Support and Relationship Quality. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Sherman, D.K.; Kim, H.S.; Jarcho, J.; Takagi, K.; Dunagan, M.S. Culture and Social Support: Who Seeks It and Why? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.Y.; Hua, L.L.; Chen, S.P.; Zhang, X.W. Research on Virtual Community Quality, Relationship Quality and Customer Engagement Behavior. J. Chang. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 21, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.L.; Chang, K.C.; Chen, M.C. The Impact of Website Quality on Customer Satisfaction and Purchase Intention: Perceived Playfulness and Perceived Flow as Mediators. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2012, 10, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Shanmugam, M.; Powell, P.; Love, P.E.D. A Study on the Continuance Participation in on-Line Communities with Social Commerce Perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 96, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, H.G. Network Drivers of Intercustomer Social Support. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations, Lexington, Kentucky, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.M.; Huang, H.Y.; Cheng, H.L.; Sun, P.C. Understanding Online Community Citizenship Behaviors through Social Support and Social Identity. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auh, S.; Bell, S.J.; McLeod, C.S.; Shih, E. Co-Production and Customer Loyalty in Financial Services. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Canevello, A. Creating and Undermining Social Support in Communal Relationships: The Role of Compassionate and Self-Image Goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Liu, R.J.; Lee, M.; Chen, J.W. When Will Consumers Be Ready? A Psychological Perspective on Consumer Engagement in Social Media Brand Communities. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Russell, D.W. Type of Social Support and Specific Stress: Toward a Theory of Optimal Matching. In Social Support: An Interactional View; Sarason, B.R., Sarason, I.G., Pierce., G.R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1900; Volume 3, pp. 319–366. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, D.J. Communicating Social Support; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Wessels, S. Self-Efficacy; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Assessing Motivation of Contribution in Online Communities: An Empirical Investigation of an Online Travel Community. Electron. Mark. 2003, 13, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C.; Gaertner, L.; Toguchi, Y. Pancultural Self-Enhancement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Maheswaran, D. The Effects of Self-Construal and Commitment on Persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.G.; Liu, J.P. Know Yourself: A Review of Related Studies on Self-Construal. J. Fujian Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 1, 160–167+172. [Google Scholar]

- Singelis, T.M. The Measurement of Independent and Interdependent Self-Construals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B.; Pantaleo, G.; Mummendey, A. Unique Individual or Interchangeable Group Member? The Accentuation of Intragroup Differences Versus Similarities as an Indicator of the Individual Self Versus the Collective Self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Bacon, P.L.; Morris, M.L. The Relational-Interdependent Self-Construal and Relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.D.; Gao, L.L.; Sheng, Z.Y.; Ma, J.J.; Guo, X.H.; Lippke, S.; Gan, Y.Q. Interdependent Self-Construal Moderates the Relationship between Pro-Generation Investment and Future Orientation: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 1008–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Markus, H.R. Deviance or Uniqueness, Harmony or Conformity? A Cultural Analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; De Cremer, D.; van den Bos, K.; Chen, Y.-R. The Influence of Interdependent Self-Construal on Procedural Fairness Effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 96, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.; Xu, Z.; CHEN, K.-m.; JIANG, Y. On Cross-Lagged Regression Mediated by Social Support: A Longitudinal Study on Effect of Interdependence Self-Construal on Mental Health. J. Southwest China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 45, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Z.Q.; Yang, Z.X.; Ling, X.H. Interdependent Self-Construal Matters in the Community Context: Relationships of Self-Construal with Community Identity and Participation. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 45, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak, C.; Vallen, B.; Sen, S. You Like What I Like, but I Don’t Like What You Like: Uniqueness Motivations in Product Preferences. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, V.; Schwayer, L.M.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E.; Wanisch, A.T. Consumers’ Self-Construal: Measurement and Relevance for Social Media Communication Success. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 959–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, R.W.; Roeder, U.R.; van Baaren, R.B.; Brandt, A.C.; Hannover, B. Don’t Stand So Close to Me–The Effects of Self-Construal on Interpersonal Closeness. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma-Kellams, C.; Blascovich, J. Inferring the Emotions of Friends Versus Strangers: The Role of Culture and Self-Construal. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H. The Psychological Mechanism of Customer Brand Engagement Behaviors: A Self-Determinant Theory Perspective. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 785. [Google Scholar]

- Zhihong, L.; Duffield, C.; Wilson, D. Research on the Driving Factors of Customer Participation in Service Innovation in a Virtual Brand Community. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2015, 7, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.; Qu, H.L. Drivers and Resources of Customer Co-Creation: A Scenario-Based Case in the Restaurant Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 64, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Huang, S.C.T.; Tsai, C.Y.D.; Lin, P.Y. Customer Citizenship Behavior on Social Networking Sites the Role of Relationship Quality, Identification, and Service Attributes. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Psychology press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mathwick, C.; Wiertz, C.; De Ruyter, K. Social Capital Production in a Virtual P3 Community. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 34, 832–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Finan, L.; Ko, I.; Koh, J.; Kim, K. The Influence of on-Line Brand Community Characteristics on Community Commitment and Brand Loyalty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2008, 12, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 119 | 40.6 |

| Women | 174 | 59.4 |

| Age range | ||

| Under 20 | 17 | 5.8 |

| From 21 to 30 | 149 | 50.9 |

| From 31 to 40 | 102 | 34.8 |

| Over 41 | 25 | 8.5 |

| Educational level | ||

| High school/technical secondary school and below | 17 | 5.8 |

| Associated degrees | 57 | 19.5 |

| Undergraduate degrees | 172 | 58.7 |

| Postgraduate degrees | 47 | 16.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Civil servant | 12 | 4.1 |

| Company manager | 46 | 15.7 |

| Ordinary employees of the enterprise | 109 | 37.2 |

| Student | 102 | 34.8 |

| Freelancer | 10 | 3.4 |

| Retired | 6 | 2.0 |

| Others | 8 | 2.7 |

| Type of VBCs | ||

| Electronic product VBCs | 100 | 34.1 |

| Automobile VBCs | 32 | 10.9 |

| Cosmetics VBCs | 82 | 28.0 |

| Game VBCs | 57 | 19.5 |

| Others | 22 | 7.5 |

| Total | 293 | 100 |

| Construct | Item | Loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informational support | IS1 | 0.695 | 0.853 | 0.593 | 0.852 |

| IS2 | 0.767 | ||||

| IS3 | 0.843 | ||||

| IS4 | 0.767 | ||||

| Emotional support | ES1 | 0.787 | 0.851 | 0.588 | 0.850 |

| ES2 | 0.771 | ||||

| ES3 | 0.777 | ||||

| ES4 | 0.732 | ||||

| Self-efficacy | SE1 | 0.772 | 0.883 | 0.654 | 0.882 |

| SE2 | 0.798 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.861 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.801 | ||||

| Interdependent self-construal | ISC1 | 0.816 | 0.915 | 0.682 | 0.914 |

| ISC2 | 0.798 | ||||

| ISC3 | 0.812 | ||||

| ISC4 | 0.857 | ||||

| ISC5 | 0.845 | ||||

| Community-oriented engagement behavior | COOEB1 | 0.661 | 0.890 | 0.576 | 0.889 |

| COOEB2 | 0.790 | ||||

| COOEB3 | 0.765 | ||||

| COOEB4 | 0.764 | ||||

| COOEB5 | 0.779 | ||||

| COOEB6 | 0.788 | ||||

| Customer-oriented engagement behavior | CUOEB1 | 0.682 | 0.859 | 0.505 | 0.859 |

| CUOEB2 | 0.738 | ||||

| CUOEB3 | 0.664 | ||||

| CUOEB4 | 0.665 | ||||

| CUOEB5 | 0.741 | ||||

| CUOEB6 | 0.766 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Informational support | 0.770 | |||||

| 2 Emotional support | 0.288 ** | 0.767 | ||||

| 3 Community-oriented engagement behavior | 0.459 ** | 0.358 ** | 0.759 | |||

| 4 Customer-oriented engagement behavior | 0.413 ** | 0.360 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.711 | ||

| 5 Self-efficacy | 0.450 ** | 0.358 ** | 0.496 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.809 | |

| 6 Interdependent self-construal | 0.237 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.320 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.269 ** | 0.826 |

| Point Estimate | SE | Z | Bias-Corrected 95%CI | Percentile 95%CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||

| indirect effects | |||||||

| IS→SE→COOEB | 0.148 ** | 0.052 | 2.846 | 0.066 | 0.274 | 0.056 | 0.258 |

| IS→SE→CUOEB | 0.132 ** | 0.049 | 2.694 | 0.055 | 0.251 | 0.046 | 0.236 |

| ES→SE→COOEB | 0.088 * | 0.041 | 2.146 | 0.028 | 0.192 | 0.022 | 0.181 |

| ES→SE→CUOEB | 0.078 * | 0.037 | 2.108 | 0.024 | 0.175 | 0.017 | 0.161 |

| direct effects | |||||||

| IS→COOEB | 0.289 ** | 0.101 | 2.861 | 0.095 | 0.484 | 0.101 | 0.488 |

| IS→CUOEB | 0.266 ** | 0.104 | 2.558 | 0.063 | 0.471 | 0.063 | 0.471 |

| ES→COOEB | 0.172 * | 0.083 | 2.072 | 0.020 | 0.345 | 0.013 | 0.337 |

| ES→CUOEB | 0.210 ** | 0.081 | 2.593 | 0.064 | 0.379 | 0.061 | 0.376 |

| total effects | |||||||

| IS→COOEB | 0.437 *** | 0.085 | 5.141 | 0.263 | 0.597 | 0.268 | 0.603 |

| IS→CUOEB | 0.398 *** | 0.093 | 4.280 | 0.212 | 0.577 | 0.211 | 0.577 |

| ES→COOEB | 0.259 ** | 0.088 | 2.943 | 0.095 | 0.437 | 0.087 | 0.430 |

| ES→CUOEB | 0.289 ** | 0.088 | 3.284 | 0.117 | 0.460 | 0.119 | 0.463 |

| Predictor Variables | Community-Oriented Engagement Behavior | Customer-Oriented Engagement Behavior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |

| Gender | −0.059 | −0.022 | −0.015 | −0.051 | −0.014 | −0.005 |

| Age | 0.019 | −0.072 | −0.069 | 0.116 * | 0.033 | 0.037 |

| Education | 0.064 | 0.091 | 0.089 | −0.008 | 0.019 | 0.016 |

| Occupation | −0.094 | −0.068 | −0.066 | −0.063 | −0.043 | −0.040 |

| Community type | −0.033 | −0.039 | −0.039 | −0.079 | −0.090 | −0.090 |

| IS | 0.403 *** | 0.413 *** | 0.337 *** | 0.348 *** | ||

| ISC | 0.241 *** | 0.296 *** | 0.254 *** | 0.320 *** | ||

| IS*ISC | 0.131 * | 0.156 ** | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.024 | 0.256 | 0.014 | 0.031 | 0.209 | 0.019 |

| F | 1.403 | 50.630 *** | 5.508 * | 1.824 | 39.252 *** | 7.444 ** |

| TOL | 0.945–0.983 | 0.903–0.960 | 0.753–0.960 | 0.945–0.983 | 0.903–0.960 | 0.753–0.960 |

| VIF | 1.017–1.058 | 1.042–1.107 | 1.042–1.328 | 1.017–1.058 | 1.042–1.107 | 1.042–1.328 |

| Predictor Variables | Community-Oriented Engagement Behavior | Customer-Oriented Engagement Behavior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | |

| Gender | −0.059 | 0.018 | 0.018 | −0.051 | 0.028 | 0.035 |

| Age | 0.019 | −0.013 | −0.013 | 0.116* | 0.086 | 0.078 |

| Education | 0.064 | 0.074 | 0.074 | −0.008 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

| Occupation | −0.094 | −0.083 | −0.083 | −0.063 | −0.051 | −0.044 |

| Community type | −0.033 | −0.094 | −0.094 | −0.079 | −0.140 ** | −0.146 ** |

| ES | 0.298 *** | 0.299 *** | 0.311 *** | 0.347 *** | ||

| ISC | 0.273 *** | 0.275 *** | 0.268 *** | 0.320 *** | ||

| ES*ISC | 0.006 | 0.164 ** | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.024 | 0.189 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.195 | 0.022 |

| F | 1.403 * | 34.316 *** | 0.012 | 1.824 | 35.967 *** | 8.339 ** |

| TOL | 0.945–0.983 | 0.914–0.964 | 0.822–0.962 | 0.945–0.983 | 0.914–0.964 | 0.822–0.962 |

| VIF | 1.017–1.058 | 1.037–1.095 | 1.040–1.217 | 1.017–1.058 | 1.037–1.095 | 1.040–1.217 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, S. Research on the Impact of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Engagement Behaviors in Virtual Brand Communities. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010031

Li X, Yang C, Wang S. Research on the Impact of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Engagement Behaviors in Virtual Brand Communities. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xuexin, Congcong Yang, and Shulin Wang. 2023. "Research on the Impact of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Engagement Behaviors in Virtual Brand Communities" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010031

APA StyleLi, X., Yang, C., & Wang, S. (2023). Research on the Impact of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Engagement Behaviors in Virtual Brand Communities. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010031