Social Media Exposure and Left-behind Children’s Tobacco and Alcohol Use: The Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Parent–Child Contact

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Media Exposure and Tobacco and Alcohol Use

1.2. Deviant Peer Affiliation as a Mediator

1.3. The Moderating Role of Materialism

1.4. Gender Differences

1.5. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Social Media Exposure

2.2.2. Deviant Peer Affiliation

2.2.3. Parent–Child Contact

2.2.4. Tobacco and Alcohol Use

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Social Media Exposure and Tobacco and Alcohol Use

4.2. Deviant Peer Affiliation as a Mediator

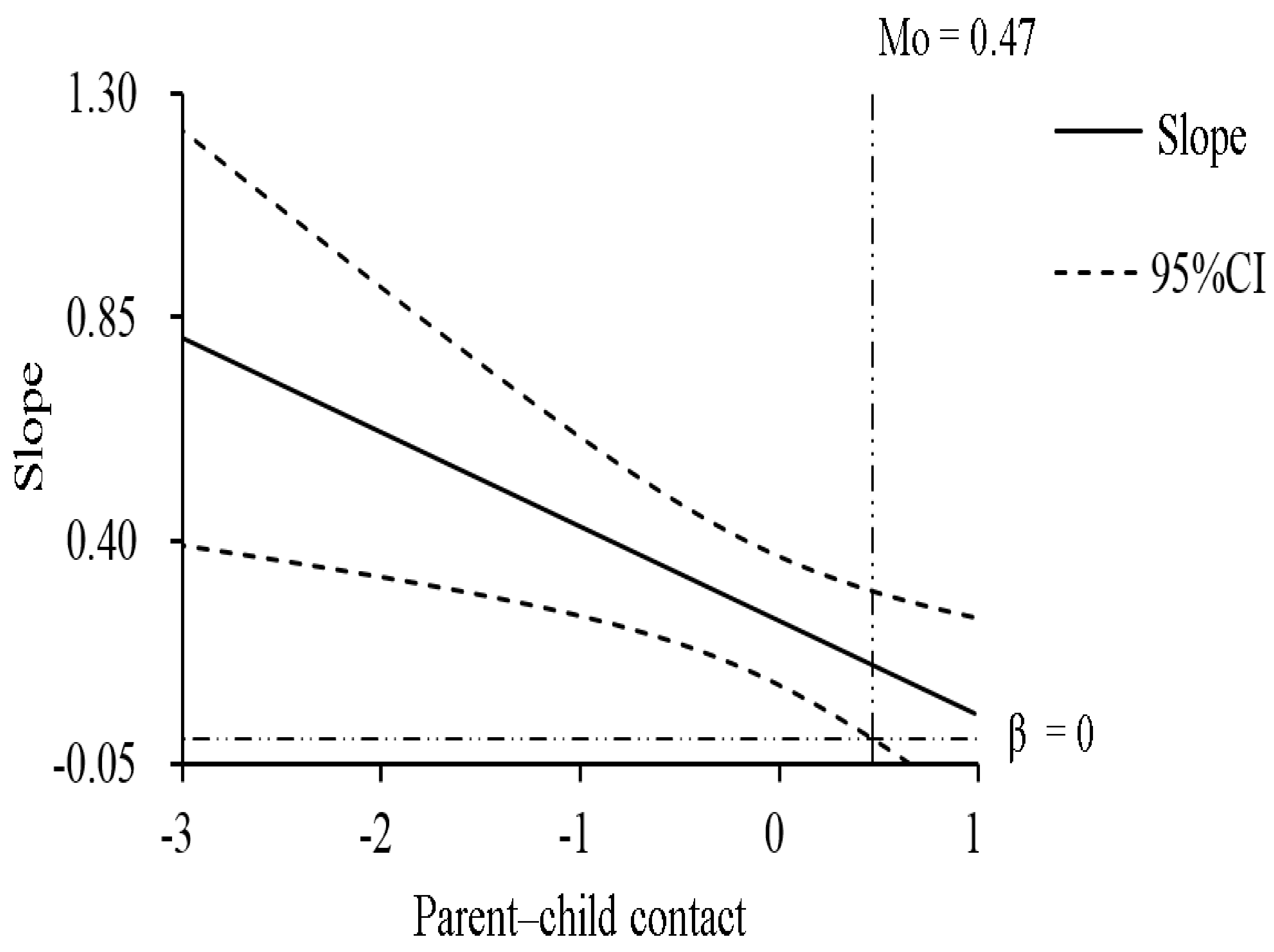

4.3. Parent–Child Contact as a Moderator

5. Implications and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, X.J.; Zhou, Z.K.; Wang, Y.; Fan, C.Y. Loneliness of children left in rural areas and its relation to peer relationship. J. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 33, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Association of Social Security. Pictures Shows the Data of Left-Behind Children in Rural Areas in 2018. 2018. Available online: http://www.caoss.org.cn/1article.asp?id=3258 (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Guo, B.C.; Zhao, M.X.; Feng, Z.Z.; Chen, X. The chain mediating role of cognitive styles and alienation between life events and depression among rural left-behind children in poor areas in Southwest China. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 306, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Xie, X.C.; Heath, M.A.; Zhou, Z.K. Psychological development and educational problems of left-behind children in rural China. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2015, 36, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanore, M.; Mazzucato, V.; Siegel, M. ‘Left behind’ but not left alone: Parental migration & the psychosocial health of children in Moldova. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 132, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.M.; Zhao, C.X.; Qi, Y.J.; He, F.; Huang, X.N.; Tian, X.B.; Sun, J.; Zheng, Y. Emotional and behavioral problems of left-behind children in impoverished rural China: A comparative cross-sectional study of fourth-grade children. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Gao, H.; Xu, G.Z. Investigation on influencing factors of smoking behavior among primary school students in Ningbo, Zhejiang province. In Proceedings of the 5th China Congress on Health Education and Health Promotion, Beijing, China, 9–11 November 2012; pp. 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Jiang, G.H.; Zhu, C.F. Investigation on alcohol drinking behavior of adolescent students in Tianjin city. Chin. J. Prev. Control Chronic Dis. 2014, 22, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.B.; Gao, M.; Ma, S.F.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.X.; Wang, M.; Su, P.Y. Relationship between onset of cigarette smoking or alcohol use in early age and multiple health-risk behaviors among middle school students in Hefei. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2004, 25, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lin, L.; Lu, J.; Cai, J.; Zhou, X. Mental health and substance use in urban left-behind children in China: A growing problem. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, C.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, S.; Chu, J.; Medina, A. Parental migration and smoking behavior of left-behind children: Evidence from a survey in rural Anhui, China. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, L.P.; Kim, J.H.; Congdon, N.; Lau, J.; Griffiths, S. The impact of parental migration on health status and health behaviors among left behind adolescent school children in China. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Smith, M.; Wolf, E.; Huang, H.M.; Chen, P.G.; Lee, L.; Emanuel, E.J. Media exposure and tobacco, illicit drugs, and alcohol use among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Subst. Abuse 2010, 31, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.H. Adolescents’ Use of Social Media: An Empirical Study of Affiliation Motive, Online Social Capital, and Sexual Opinions Dissemination. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, J.B.; Triu, P.; Ellison, N.B. Social media elements, ecologies, and effects. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 471–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M.A.; Whitehill, J.M. # Wasted: The intersection of substance use behaviors and social media in adolescents and young adults. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 9, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L.; Leung, L. Migrant parenting and mobile phone use: Building quality relationships between Chinese migrant workers and their left-behind children. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 2017, 12, 925–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.F.; Bao, N.; Zhou, Z.K.; Fan, C.Y.; Kong, F.C.; Sun, X.J. The impact of self-presentation in online social network sites on life satisfaction: The effect of positive affect and social support. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2015, 31, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, J.; Spradling, M. Americans’ perspectives on online media warning labels. Behav. Sci. 2019, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.C.; Unger, J.B.; Soto, D.; Fujimoto, K.; Pentz, M.A.; Jordan-Marsh, M.; Valente, T.W. Peer influences: The impact of online and offline friendship networks on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgate, E.C.; Holliday, J. Identity, influence, and intervention: The roles of social media in alcohol use. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 9, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beullens, K.; Schepers, A. Display of alcohol use on Facebook: A content analysis. Cyberpsych. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.A.; Briner, L.R.; Williams, A.; Brockman, L.; Walker, L.; Christakis, D.A. A content analysis of displayed alcohol references on a social networking web site. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 47, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Shanahan, J. The state of cultivation. J. Broadcast. Electron. 2010, 54, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Salmon, C.T.; Pang, J.S.; Cheng, W.J. Media exposure and smoking intention in adolescents: A moderated mediation analysis from a cultivation perspective. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.; Yang, J.; Cho, E. How social media influence college students’ smoking attitudes and intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, J.S.; Miles, J.N.; D’Amico, E.J. Cross-lagged associations between substance use-related media exposure and alcohol use during middle school. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013, 53, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gardner, M.; Steinberg, L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.M.; Chong, M.Y.; Cheng, A.T.A.; Chen, T.H.H. Correlates of family, school, and peer variables with adolescent substance use in Taiwan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2594–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.J.; Li, D.P.; Gu, C.H.; Zhao, L.Y.; Bao, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.H. Parental control and adolescents’ problematic internet use: The mediating effect of deviant peer affiliation. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2014, 3, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Li, D.; Jia, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y. Peer victimization and problematic internet use in adolescents: The mediating role of deviant peer affiliation and the moderating role of family functioning. Addict. Behav. 2019, 96, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Trucco, E.M.; Colder, C.R.; Wieczorek, W.F. Vulnerability to peer influence: A moderated mediation study of early adolescent alcohol use initiation. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambron, C.; Kosterman, R.; Catalano, R.F.; Guttmannova, K.; Hawkins, J.D. Neighborhood, family, and peer factors associated with early adolescent smoking and alcohol use. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Yoon, S.; Yoon, M.; Snyder, S.M. Developmental trajectories of deviant peer affiliation in adolescence: Associations with types of child maltreatment and substance use. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 105, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.J.; Zaharakis, N.M.; Rusby, J.C.; Westling, E.; Flay, B.R. A longitudinal study predicting adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use by behavioral characteristics of close friends. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2017, 31, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tickle, J.J.; Sargent, J.D.; Dalton, M.A.; Beach, M.L.; Heatherton, T.F. Favourite movie stars, their tobacco use in contemporary movies, and its association with adolescent smoking. Tobacco Control 2001, 10, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beullens, K.; Vandenbosch, L. A conditional process analysis on the relationship between the use of social networking sites, attitudes, peer norms, and adolescents’ intentions to consume alcohol. Media Psychol. 2016, 9, 310–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, D.M.; Stock, M.L. Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: The roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011, 25, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Cin, S.; Worth, K.A.; Gerrard, M.; Gibbons, F.X.; Stoolmiller, M.; Wills, T.A.; Sargent, J.D. Watching and drinking: Expectancies, prototypes, and friends’ alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.Y.; Chu, X.W.; Niu, G.F.; Sun, X.J.; Lian, S.L.; Yao, L.S.; Yang, P.F.; Zhao, D.M. Self-disclosure on social networking sites and adolescents’ life satisfaction: A moderated mediation model. J. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 41, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete, J.; Araya, R. Individual and contextual factors associated with tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use among Chilean adolescents: A multilevel study. J. Adolesc. 2017, 56, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.M.; Puplampu, P. A conceptual framework for understanding the effect of the Internet on child development: The ecological techno-subsystem. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 2008, 34, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daspe, M.; Reout, A.; Ramos, M.C.; Shapiro, L.A.S.; Margolin, G. Deviant peers and adolescent risky behaviors: The protective effect of nonverbal display of parental warmth. J. Res. Adolesc. 2018, 29, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.Y. Maternal attachment, parental monitoring and adolescent smoking and drinking behavior. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 1995, 3, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi, T. Causes of Delinquency; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L. Research for the Influence of Left-Behind Children’s Individual Development for the Reason of Parent-Child Separation—Take Ningxia H Primary School for Example. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, T.; Dai, B.R. Quality of life status and influencing factor of left-behind children in rural areas. China J. Health Psychol. 2019, 27, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Diao, H.; Ran, M.; Yang, J.W.; Yang, L.J.; Li, T. Quality of life among left-behind adolescents in rural Chongqing. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2018, 39, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, J.J.; Yu, C.F.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lu, Z.H. Exposure to community violence and externalizing problem behavior among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2017, 33, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.J.; Yu, Y.P.; Ng, T.K. A study on the moderating effect of family functioning on the relationship between deviant peer affiliation and delinquency among Chinese adolescents. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2013, 3, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Luo, F.; Ren, P. Effects of neighborhood, parental monitoring and deviant peers on adolescent problem behaviors. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2017, 33, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.X.; Li, Q.Y.; Wang, L.W.; Lin, L.Y.; Zhang, W.X. Latent profile analysis of left-behind adolescents’ psychosocial adaptation in rural China. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1146–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, S.C.; LaBrie, J.W.; Froidevaux, N.M.; Witkovic, Y.D. Different digital paths to the keg? How exposure to peers’ alcohol-related social media content influences drinking among male and female first-year college students. Addict. Behav. 2016, 57, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Chaput, J.P. Use of social networking sites and alcohol consumption among adolescents. Public Health 2016, 139, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.Y. Parental monitoring and peer pressure: Gender differences in deviant behavior of middle school students. J. Weifang Eng. Vocat. Coll. 2019, 32, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal, M.P.; Chassin, L. Peer influence on adolescent alcohol use: The moderating role of parental support and discipline. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2000, 4, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.F.; Li, Z.X.; Wang, C.X.; Ma, X.T.; Sun, X.J.; Zhou, Z.K. The influence of online parent-child communication on left-behind Junior high school students’ social adjustment: A moderated mediation model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 678–685. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.S.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Y.Q.; Zhu, C.Y.; Sun, H.L. Influence of parent-adolescent communication on behavioral problems of left-behind children. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 22, 1118–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, B.J.; Li, D.P.; Chen, Q.S.; Wang, Y.H. Sensation seeking and tobacco and alcohol use among adolescents: A mediated moderation model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2011, 4, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wen, Z.L.; Liang, D.M.; Li, N.N. Moderation effect analyses based on multiple linear regression. J. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 38, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, K.C.; Scull, T.M.; Kupersmidt, J.B. Media as a “Super Peer”: How adolescents interpret media messages predicts their perception of alcohol and tobacco use norms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, A.W.; Widaman, K.F.; Marlatt, G.A. Expectancy models of alcohol use. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H. Research into media exposure behaviors of left-behind children in rural areas from the perspective of media as substitutes. High. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 8, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.P. Research on ways of media literacy education for rural left-behind children in the omni-media era. Sci. Educ. Art. Collects 2017, 3, 116–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Youth & Children Research Center. A Research Report on the Situation of Left-Behind Children in Rural China. Available online: http://qnzz.youth.cn/zhuanti/10wdmgxlt/jcsj/201412/t20141202_6150438.htm (accessed on 1 December 2014).

- Niu, G.F.; Wu, Y.; Yan, L. The influence of discrimination perception on mobile phone addiction of left-behind children: The mediating role of deviant peer interaction and the moderating role of self-control. J. Yangtze Univ. 2020, 43, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.J.; Zhang, L.; Ren, Y.L.; Xiao, L.X.; Zhang, Q.H. Parent—Child cohesion, basic psychological needs satisfaction, and emotional adaptation in left—behind children in China: An indirect effects model. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.Y. Research on the Relationship between Problem Behavior and Parent-Child Communication of Junior Middle School. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.J.; Shang, L. Reliability and validity of adolescent risk-taking questionnaire-risk behavior scale (ARQ-RB) in middle school students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2011, 8, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.F.; Chai, H.Y.; Li, Z.X.; Wu, L.; Sun, X.J.; Zhou, Z.K. Online parent-child communication and left-behind children’s subjective well-being: The effects of parent-child relationship and gratitude. Child. Indic. Res. 2022, 13, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartanto, A.; Quek, F.Y.; Tng, G.Y.Q.; Yong, J.C. Does social media use increase depressive symptoms? A reverse causation perspective. Front. Psychiatry. 2021, 12, 641934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Left-Behind Children Psychological Conditions White Paper. Available online: http://www.sxlsngo.com/schooladmin/audio/index/type/2 (accessed on 16 October 2018).

| Boys | Girls | Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M (SD) | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1. Social media exposure | 1.68 (0.84) | 1.55 (0.67) | 1 | 0.28 *** | −0.11 | 0.30 *** |

| 2. Deviant peer affiliation | 1.48 (0.68) | 1.26 (0.47) | 0.25 *** | 1 | −0.14 * | 0.27 *** |

| 3. Parent–child contact | 3.93 (1.01) | 4.02 (1.00) | −0.03 | −0.08 | 1 | −0.11 |

| 4. Tobacco and alcohol use | 1.25 (0.62) | 1.04 (0.17) | 0.27 *** | 0.30 *** | −0.04 | 1 |

| Regression Equation | Fitting Index | Significance of Coefficients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Predictors | R2 | F | b | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

| Deviant peer affiliation | 0.14 | 8.86 *** | |||||

| Age | 0.11 *** | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.16 | |||

| Duration of being left behind | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.09 | |||

| Type of being left behind | 0.08 | 0.14 | −0.19 | 0.35 | |||

| Social media exposure | 0.18 *** | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.30 | |||

| Tobacco and alcohol use | 0.18 | 5.82 *** | |||||

| Age | 0.07 * | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.12 | |||

| Duration of being left behind | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.11 | |||

| Type of being left behind | 0.02 | 0.11 | −0.17 | 0.20 | |||

| Social media exposure (SME) | 0.17 ** | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.31 | |||

| Deviant peer affiliation (DPA) | 0.24 *** | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.39 | |||

| Parent–child contact (PCC) | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.20 | |||

| SME × PCC | 0.08 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.23 | |||

| DPA × PCC | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.10 | 0.13 | |||

| Regression Equation | Fitting Index | Significance of Coefficients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Predictors | R2 | F | b | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

| Deviant peer affiliation | 0.12 | 5.87 *** | |||||

| Age | 0.06 * | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.11 | |||

| Duration of being left behind | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.08 | |||

| Type of being left behind | −0.08 | 0.13 | −0.37 | 0.22 | |||

| Social media exposure | 0.22 *** | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.34 | |||

| Tobacco and alcohol use | 0.20 | 5.51 *** | |||||

| Age | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.03 | |||

| Duration of being left behind | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.13 | |||

| Type of being left behind | −0.07 | 0.16 | −0.33 | 0.19 | |||

| Social media exposure (SME) | 0.25 *** | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.41 | |||

| Deviant peer affiliation (DPA) | 0.32 *** | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.50 | |||

| Parent–child contact (PCC) | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.20 | 0.10 | |||

| SME × PCC | −0.22 ** | 0.08 | −0.38 | −0.06 | |||

| DPA × PCC | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.13 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, L.; Yao, L.; Guo, Y. Social Media Exposure and Left-behind Children’s Tobacco and Alcohol Use: The Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Parent–Child Contact. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080275

Wu L, Yao L, Guo Y. Social Media Exposure and Left-behind Children’s Tobacco and Alcohol Use: The Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Parent–Child Contact. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(8):275. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080275

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Li, Liangshuang Yao, and Yuanxiang Guo. 2022. "Social Media Exposure and Left-behind Children’s Tobacco and Alcohol Use: The Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Parent–Child Contact" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 8: 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080275

APA StyleWu, L., Yao, L., & Guo, Y. (2022). Social Media Exposure and Left-behind Children’s Tobacco and Alcohol Use: The Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Parent–Child Contact. Behavioral Sciences, 12(8), 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080275