Fear of Losing Jobs during COVID-19: Can Psychological Capital Alleviate Job Insecurity and Job Stress?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping

2.2. Perceptions of Job Insecurity and Job Stress

2.3. The Role of Psychological Capital

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Survey Measures

3.3. Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

3.4. Analytic Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Multilevel Considerations

4.2. Measurement Models

4.3. Structural Models

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, A. How COVID-19 Is Impacting the Banking Workforce. International Banker. Available online: https://internationalbanker.com/banking/how-covid-19-is-impacting-the-banking-workforce/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- The Nation Thailand. Over 800 Thai Bank Branches Shuttered during Past Year. The Nation Thailand. 24 April 2022. Available online: https://www.nationthailand.com/business/40014873 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Baicu, C.G.; Gârdan, I.P.; Gârdan, D.A.; Epuran, G. The Impact of COVID-19 on Consumer Behavior in Retail Banking. Evidence from Romania. Manag. Mark. 2020, 15 (Suppl. S1), 534–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, M.; Liu, L.; Mysore, M. McKinsey & Company: COVID-19— Implications for Business; Internatioanl Parking & Mobility Institute: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.parking-mobility.org/2020/04/06/mckinsey-company-covid-19-implications-for-business/ (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Sverke, M.; Hellgren, J.; Näswall, K. No Security: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Job Insecurity and Its Consequences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.K.; Kramer, A.; Pak, S. Job Insecurity and Subjective Sleep Quality: The Role of Spillover and Gender. Stress Health 2021, 37, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H.; Näswall, K. ‘Objective’ vs ‘Subjective’ Job Insecurity: Consequences of Temporary Work for Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Four European Countries. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2003, 24, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staufenbiel, T.; König, C.J. A Model for the Effects of Job Insecurity on Performance, Turnover Intention, and Absenteeism. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Spiegelaere, S.; Van Gyes, G.; De Witte, H.; Niesen, W.; Van Hootegem, G. On the Relation of Job Insecurity, Job Autonomy, Innovative Work Behaviour and the Mediating Effect of Work Engagement. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2014, 23, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K. Job Insecurity and Health: The Moderating Role of Workplace Control. Stress Med. 1996, 12, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Othman, A.; Wahab, M.N.A.; Safaria, T. Religious Coping, Job Insecurity and Job Stress among Javanese Academic Staff: A Moderated Regression Analysis. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2010, 2, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Ali, F. Job Insecurity, Subjective Well-Being and Job Performance: The Moderating Role of Psychological Capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, L.; Rosenblatt, Z. Job Insecurity: Toward Conceptual Clarity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lansisalmi, H.; Peiro, J.M.; Kivimaki, M., IV. Collective Stress and Coping in the Context of Organizational Culture. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2000, 9, 527–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisel, W.D.D.; Probst, T.M.M.; Chia, S.L.L.; Maloles, C.M.M.; König, C. The Effects of Job Insecurity on Job Satisfaction, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Deviant Behavior, and Negative Emotions of Employees. International Studies of Management and Organization. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2010, 40, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jamal, M. Job Stress and Job Performance Controversy: An Empirical Assessment. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1984, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. From Psychological Stress to the Emotions: A History of Changing Outlooks. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1993, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.E.; Decotiis, T.A. Organizational Determinants of Job Stress. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1983, 32, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuler, R.S. Definition and Conceptualization of Stress in Organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1980, 25, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve, M.; Schuster, C.; Albareda, A.; Losada, C. The Effects of Doing More with Less in the Public Sector: Evidence from a Large-Scale Survey. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.E.; Park, C.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, S. The Stress-Induced Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism and Hospitality Workers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 31327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Malik, M.I.; Qureshi, S.S. Work Stress Hampering Employee Performance during COVID-19: Is Safety Culture Needed? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Quintana, T.; Nguyen, H.; Araujo-Cabrera, Y.; Sanabria-Díaz, J.M. Do Job Insecurity, Anxiety and Depression Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic Influence Hotel Employees’ Self-Rated Task Performance? The Moderating Role of Employee Resilience. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Arasli, H.; Kilic, H. Effect of Job Insecurity on Frontline Employee’s Performance: Looking through the Lens of Psychological Strains and Leverages. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1724–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Varley, D.; Allgar, V.L.; de Beurs, E. Workplace Stress, Presenteeism, Absenteeism, and Resilience Amongst University Staff and Students in the COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 588803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Liu, X.; Fang, R. Evaluation of the Correlation between Job Stress and Sleep Quality in Community Nurses. Medicine 2020, 99, e18822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Thayer, J.F.; Vedhara, K. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive Psychological Capital: Measurement and Relationship with Performance and Satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiesa, R.; Fazi, L.; Guglielmi, D.; Mariani, M.G. Enhancing Substainability: Psychological Capital, Perceived Employability, and Job Insecurity in Different Work Contract Conditions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, S.; Neves, P. Job Insecurity and Work Outcomes: The Role of Psychological Contract Breach and Positive Psychological Capital. Work Stress 2017, 31, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S.; Mishra, U.S.; Mishra, B.B. Can Psychological Capital Reduce Stress and Job Insecurity? An Experimental Examination with Indian Evidence. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ren, Z.; Wang, Q.; He, M.; Xiong, W.; Ma, G.; Fan, X.; Guo, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. The Relationship between Job Stress and Job Burnout: The Mediating Effects of Perceived Social Support and Job Satisfaction. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.J. A Resources–Demands Approach to Sources of Job Insecurity: A Multilevel Meta-Analytic Investigation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2020, 26, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, S.; Martin, A.; Scott, J.; Sanderson, K. Advancing Conceptualization and Measurement of Psychological Capital as a Collective Construct. Hum. Relat. 2015, 68, 925–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.H.; Kao, K.Y. Beyond Individual Job Insecurity: A Multilevel Examination of Job Insecurity Climate on Work Engagement and Job Satisfaction. Stress Health 2021, 38, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Probst, T.M. A Multilevel Examination of Affective Job Insecurity Climate on Safety Outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sora, B.; Caballer, A.; Peiró, J.M.; Silla, I.; Gracia, F.J. Moderating Influence of Organizational Justice on the Relationship between Job Insecurity and Its Outcomes: A Multilevel Analysis. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2010, 31, 613–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrek, S.; Cullen, M.R. Job Insecurity during Recessions: Effects on Survivors’ Work Stress. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Skaff, M.M.K. Stress and the Life Course: A Paradigmatic Alliance. Gerontologist 1996, 36, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debus, M.E.; König, C.J.; Kleinmann, M. The Building Blocks of Job Insecurity: The Impact of Environmental and Person-Related Variables on Job Insecurity Perceptions. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, A.C.; Landis, R.S.; Pierce, C.A.; Earnest, D.R. Why Do Employees Worry about Their Jobs? A Meta-Analytic Review of Predictors of Job Insecurity. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Peterson, S.J. The Development and Resulting Performance Impact of Positive Psychological Capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2010, 21, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heaney, C.A.; Israel, B.A.; House, J.S. Chronic Job Insecurity among Automobile Workers: Effects on Job Satisfaction and Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 38, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C.; Bobko, P. Content, Causes, and Consequences of Job Insecurity: A Theory-Based Measure and Substantive Test. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 803–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M. Job insecurity. In Handbook of Organizational Behavior; Cooper, C.L., Barling, J., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 178–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren, J.; Sverke, M.; Isaksson, K. A Two-Dimensional Approach to Job Insecurity: Consequences for Employee Attitudes and Well-Being. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Huang, G.H.; Ashford, S.J. Job Insecurity and the Changing Workplace: Recent Developments and the Future Trends in Job Insecurity Research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Witte, H. Job Insecurity: Review of the International Literature on Definitions, Prevalence, Antecedents and Consequences. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2005, 31, a200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abildgaard, J.S.; Nielsen, K.; Sverke, M. Can Job Insecurity Be Managed? Evaluating an Organizational-Level Intervention Addressing the Negative Effects of Restructuring. Work Stress 2018, 32, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackmore, C.; Kuntz, J.R. Antecedents of Job Insecurity in Restructuring Organisations: An Empirical Study. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2011, 40, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, T. Technology Usage, Expected Job Sustainability, and Perceived Job Insecurity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 138, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Saenz Molina, J.; Saenz, J.; Federal, M. “Forced Automation” by COVID-19? Early Trends from Current Population Survey Data; Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Erebak, S.; Turgut, T. Anxiety about the Speed of Technological Development: Effects on Job Insecurity, Time Estimation, and Automation Level Preference. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2021, 32, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.; Curtis, C.; Ryan, B. Examining the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Hotel Employees through Job Insecurity Perspectives. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingmont, D.N.J.; Alexiou, A. The Contingent Effect of Job Automating Technology Awareness on Perceived Job Insecurity: Exploring the Moderating Role of Organizational Culture. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Malik, M.; Sarwat, N. Consequences of Job Insecurity for Hospitality Workers amid COVID-19 Pandemic: Does Social Support Help? J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 957–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemteanu, M.S.; Dinu, V.; Dabija, D.C. Job Insecurity, Job Instability, and Job Satisfaction in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, K.T.; Tsai, A.C.; Weiser, S.D.; Benabou, S.E.; Nagata, J.M. Job Insecurity and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Among U.S. Young Adults During COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Låstad, L.; Näswall, K.; Berntson, E.; Seddigh, A.; Sverke, M. The Roles of Shared Perceptions of Individual Job Insecurity and Job Insecurity Climate for Work- and Health-Related Outcomes: A Multilevel Approach. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2018, 39, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sora, B.; Caballer, A.; Peiró, J.M.; de Witte, H. Job Insecurity Climate’s Influence on Employees’ Job Attitudes: Evidence from Two European Countries. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2009, 18, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Luthans, K.W.; Luthans, B.C. Positive Psychological Capital: Beyond Human and Social Capital. Bus. Horiz. 2004, 47, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. A Resource Perspective on the Work-Home Interface: The Work-Home Resources Model. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Snyder, C.R.; Rand, K.L.; Sigmon, D.R. Hope theory. In The Oxford Handbook of Hope; Gallagher, M.W., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieselbach, T.; Beelmann, G.; Wagner, O. Job Insecurity and Successful Re-Employment: Examples from Germany. In Coping with Occupational Transitions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 115–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Pajares, F. The development of academic self-efficacy. In Development of Achievement Motivation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Vogelgesang, G.R.; Lester, P.B. Developing the Psychological Capital of Resiliency. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2006, 5, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources and Disaster in Cultural Context: The Caravans and Passageways for Resources. Psychiatry 2012, 75, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Tooley, E.M.; Christopher, P.J.; Kay, V.S. Resilience as the Ability to Bounce Back from Stress: A Neglected Personal Resource? J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabenu, E.; Yaniv, E. Psychological Resources and Strategies to Cope with Stress at Work. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2017, 10, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, D.D. Resilience and the ability to anticipate. In Resilience Engineering in Practice: A Guidebook; Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2011; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Fulford, D. Optimism. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Dispositional Optimism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seligman, M.E.P. The prediction and prevention of depression. In The Science of Clinical Psychology: Accomplishments and Future Directions; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Connor-Smith, J. Personality and Coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ohlin, B. Psycap 101: Your Guide to Increasing Psychological Capital. Positive Psychological. Available online: https://positivepsychology.com/psychological-capital-psycap/ (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. Coping as a Mediator of Emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M.; Gailey, N.J.; Jiang, L.; Bohle, S.L. Psychological Capital: Buffering the Longitudinal Curvilinear Effects of Job Insecurity on Performance. Saf. Sci. 2017, 100, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Oke, A. Authentically Leading Groups: The Mediating Role of Collective Psychological Capital and Trust. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.M.; Chen, T.J. Collective Psychological Capital: Linking Shared Leadership, Organizational Commitment, and Creativity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H. Arbeidsethos En Jobonzekerheid: Meting En Gevolgen Voor Welzijn, Tevredenheid En Inzet Op Het Werk [Work Ethic and Job Insecurity: Assessment and Consequences for Wellbeing, Satisfaction and Performance at Work]. In Van Groep Naar Gemeenschap [From Group to Community]; Bouwen, K., De Witte, H., Witte, D., Taillieu, T., Eds.; Garant: Leuven, Belgium, 2000; pp. 325–350. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. Perceived Stress in a Probability Sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health; PsycNET, Spacapan, S., Oskamp, S., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.H.L.; Chan, D.K.S. Who Suffers More from Job Insecurity? A Meta-Analytic Review. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 272–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, E. Model Fit Evaluation in Multilevel Structural Equation Models. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hox, J.J.; Maas, C.J.M.; Brinkhuis, M.J.S. The Effect of Estimation Method and Sample Size in Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling. Stat. Neerl. 2010, 64, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zyphur, M.J.; Zhang, Z. A General Multilevel SEM Framework for Assessing Multilevel Mediation. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- LeBreton, J.M.; Senter, J.L. Answers to 20 Questions about Interrater Reliability and Interrater Agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Personality, Affect, and Behavior in Groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, J. Use of Partial Least Squares (PLS) in Strategic Management Research: A Review of Four Recent Studies. Strateg. Manag. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K. Job Insecurity: An Integrative Review and Agenda for Future Research. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1911–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, S.W.J.; Klein, K.J. A Multilevel Approach to Theory and Research in Organizations: Contextual, Temporal, and Emergent Processes. In Multilevel Theory, Research and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 3–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bilotta, I.; Cheng, S.K.; Ng, L.C.; Corrington, A.R.; Watson, I.; King, E.B.; Hebl, M.R. Softening the Blow: Incorporating Employee Perceptions of Justice into Best Practices for Layoffs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. Policy 2020, 6, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Greenberg, J. The Impact of Layoffs on Survivors: An Organizational Justice Perspective. Appl. Soc. Psychol. Organ. Settings 2015, 45, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D. Functional Relations Among Constructs in the Same Content Domain at Different Levels of Analysis: A Typology of Composition Models. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychology Capital | 4.68 | 0.95 | (0.95) | ||||||||

| 2. Job Insecurity | 2.77 | 1.06 | −0.15 ** | (0.88) | |||||||

| 3. Job Stress | 2.75 | 0.89 | −0.05 | 0.45 ** | (0.88) | ||||||

| 4. Gender | - | - | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 | - | |||||

| 5. Age | 33.90 | 7.23 | 0.15 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.13 ** | |||||

| 6. Education | - | - | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.27 ** | ||||

| 7. Tenure (years) | 7.79 | 6.57 | 0.13 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.05 | 0.80 ** | 0.24 ** | |||

| 8. Salary (Baht) | - | - | 0.08 | −0.11 * | −0.13 ** | 0.01 | 0.12 ** | 0.07 | 0.08 ** | ||

| 9. Contract Types | - | - | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.24 ** | −0.15 ** | 0.20 | −0.02 | |

| 10. Hierarchical Positions | - | - | −0.01 | −0.19 ** | −0.23 ** | 0.03 | 0.51 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.21 ** |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Collective Psychological Capital | 4.68 | 0.50 | (0.96) | ||

| 2. Job insecurity Climate | 2.77 | 0.62 | −0.15 | (0.94) | |

| 3. Collective Job Stress | 2.75 | 0.51 | −0.10 | 0.70 ** | (0.92) |

| Latent Constructs and Manifest Indicators | Loadings within Level N = 520 | Loadings between Level N = 53 |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological capital | (0.93; 0.98) | (1.00; 1.00) |

| 1. Self-efficacy | 0.929 | 1.007 |

| 1.1 I feel confident in representing my work area in meetings with management. | 0.801 | 0.880 |

| 1.2 I feel confident contributing to discussions about the organization’s strategy. | 0.806 | 0.984 |

| 1.3 I feel confident presenting information to a group of colleagues | 0.874 | 0.971 |

| 2. Hope | 0.988 | 1.000 |

| 2.1 If I should find myself in a jam at work, I could think of many ways to get out of it | 0.846 | 0.989 |

| 2.2 Right now, I see myself as being successful at work | 0.805 | 0.988 |

| 2.3 I can think of many ways to reach my current work goals. | 0.879 | 1.000 |

| 2.4 At this time, I am meeting the work goals that I have set for myself | 0.836 | 0.981 |

| 3. Resilience | 0.994 | 0.983 |

| 3.1 I can be “on my own,” so to speak, at work if I have to. | 0.861 | 1.004 |

| 3.2 I can get through difficult times at work because I’ve experienced difficulty before | 0.837 | 0.988 |

| 4. Optimism | 0.943 | 1.021 |

| 4.1 I always look on the bright side of things regarding my job. | 0.847 | 0.956 |

| 4.2 I am optimistic about what will happen to me in the future as it pertains to work. | 0.892 | 0.960 |

| Job Insecurity | (0.62; 0.86) | (0.87; 0.96) |

| 1. Chances are, I will soon lose my job. | 0.798 | 0.945 |

| 2. I am not sure whether I can keep my job. | 0.605 | 0.779 |

| 3. I feel insecure about the future of my job. | 0.864 | 1.011 |

| 4. I think I might lose my job in the near future. | 0.850 | 0.982 |

| Job Stress | (0.57; 0.90) | (0.93; 0.99) |

| 1. In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | 0.749 | 0.974 |

| 2. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? | 0.758 | 0.941 |

| 3. In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and “stressed”? | 0.788 | 0.961 |

| 4. In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | 0.722 | 0.913 |

| 5. In the last month, how often have you been able to control irritations in your life? (Reverse-coded) | 0.680 | 0.994 |

| 6. In the last month, how often have you been angered because of things that were outside of your control? | 0.821 | 1.002 |

| 7. In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them? | 0.769 | 0.980 |

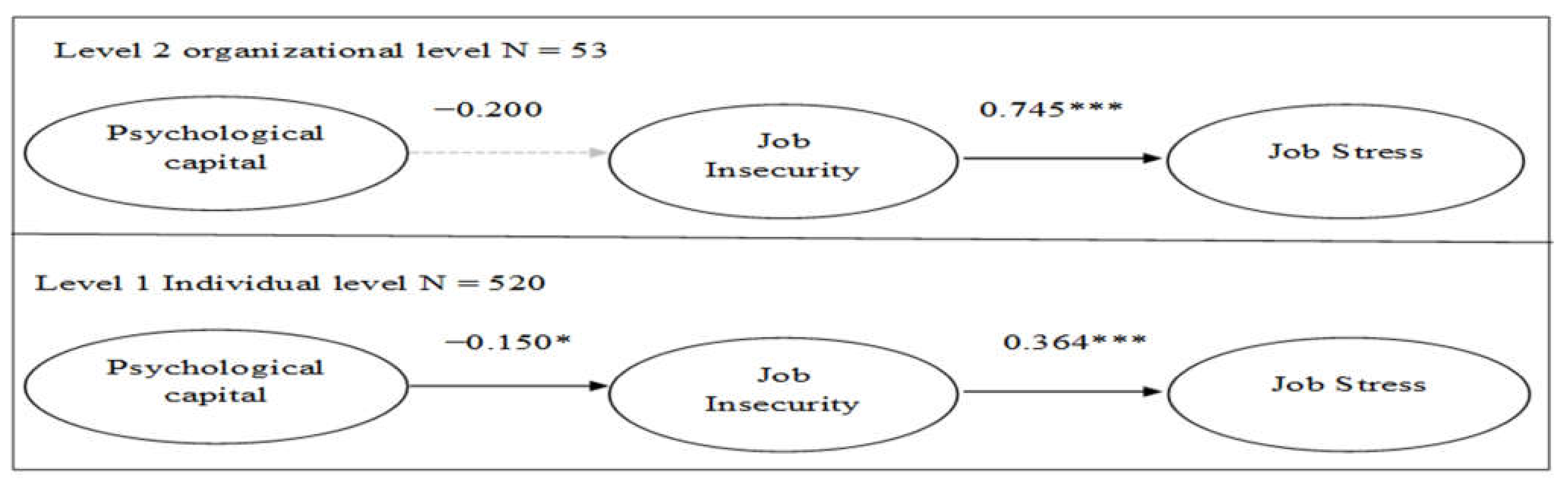

| Estimated Paths | Within Level (N = 520) | Between Level (N = 53) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | b | b | b | |

| Job Insecurity | Job Stress | Job Insecurity | Job Stress | |

| Main Analyses | ||||

| Psychological Capital | −0.150 * | - | −0.200 | - |

| Job insecurity | - | 0.364 *** | - | 0.745 *** |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Gender (1 = female) | −0.087 | 0.184 * | - | - |

| Age | −0.042 | −0.003 | - | - |

| Education | 0.020 | −0.077 | - | - |

| Tenure | −0.165 * | 0.003 | - | - |

| Salary | −0.047 | −0.001 | - | - |

| Contract types (1 = permanent) | −0.005 | −0.252 | - | - |

| Positions (1 = senior) | −0.143 * | −0.167 * | - | - |

| Explained variance (R2) | ||||

| Job insecurity | 0.113 ** | - | 0.037 | - |

| Job Stress | - | 0.291 *** | - | 0.668 ** |

| Mediated Paths | Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCL | ULCL | |||

| Within level (N = 520) | ||||

| Psychological Capital → Job insecurity → Job stress | −0.054 * | 0.027 | −0.099 | −0.015 |

| Between level (N = 53) | ||||

| Psychological Capital → Job insecurity → Job stress | −0.149 | 0.225 | −0.582 | 0.262 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, B.; Potipiroon, W. Fear of Losing Jobs during COVID-19: Can Psychological Capital Alleviate Job Insecurity and Job Stress? Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12060168

Peng B, Potipiroon W. Fear of Losing Jobs during COVID-19: Can Psychological Capital Alleviate Job Insecurity and Job Stress? Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(6):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12060168

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Bangxin, and Wisanupong Potipiroon. 2022. "Fear of Losing Jobs during COVID-19: Can Psychological Capital Alleviate Job Insecurity and Job Stress?" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 6: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12060168

APA StylePeng, B., & Potipiroon, W. (2022). Fear of Losing Jobs during COVID-19: Can Psychological Capital Alleviate Job Insecurity and Job Stress? Behavioral Sciences, 12(6), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12060168