Frontline Service Employees’ Profiles: Exploring Individual Differences in Perceptions of and Reactions to Workplace Incivility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background Literature

2.1. Workplace Incivility and Job Outcomes

2.2. The Role of Individual Characteristics and Personality Traits

2.3. Workplace Social Supports

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Procedure

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

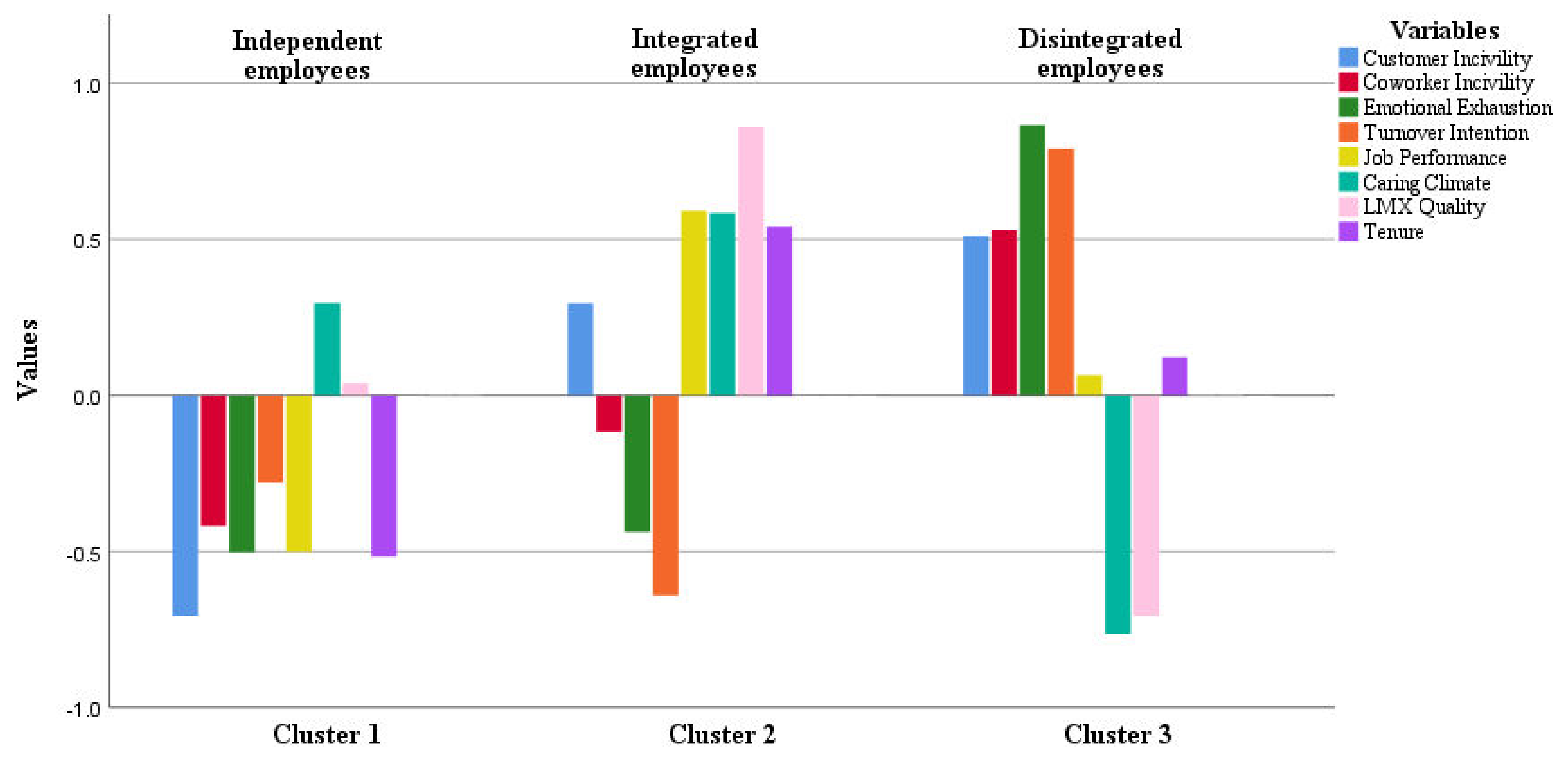

4.1. Independent Employees

4.2. Integrated Employees

4.3. Disintegrated Employees

5. Discussion

6. Knowledge and Research Implications

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Shah, S.I. Frontline employees’ high-performance work practices, trust in supervisor, job-embeddedness and turnover intentions in hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1436–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Bonn, M.A.; Cho, M. The relationship between customer incivility, restaurant frontline service employee burnout and turnover intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Reio, T.G., Jr.; Bang, H. Reducing turnover intent: Supervisor and co-worker incivility and socialization-related learning. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2013, 16, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskin, M.; Surucu, O.A. The role of polychronicity and intrinsic motivation as personality traits on frontline employees’ job outcomes. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Admin. 2016, 8, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A.; Karatepe, O.M. Frontline hotel employees’ psychological capital, trust in organization, and their effects on nonattendance intentions, absenteeism, and creative performance. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 2019, 28, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, A.H. Investigating factors that influence employees’ turnover intention: A review of existing empirical works. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sliter, M.; Sliter, K.; Jex, S. The employee as a punching bag: The effect of multiple sources of incivility on employee withdrawal behavior and sales performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.C.; Koopman, J.; Gabriel, A.S.; Johnson, R.E. Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when and why incivility begets incivility. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1620–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arasli, H.; Hejraty Namin, B.; Abubakar, A.M. Workplace incivility as a moderator of the relationships between polychronicity and job outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1245–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Moon, T.W.; Han, S.J. The effect of customer incivility on service employees’ customer orientation through double-mediation of surface acting and emotional exhaustion. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2015, 25, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Cosby, D.M. A model of workplace incivility, job burnout, turnover intentions, and job performance. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alola, U.V.; Olugbade, O.A.; Avci, T.; Öztüren, A. Customer incivility and employees’ outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Jex, S.; Wolford, K.; McInnerney, J. How rude! Emotional labor as a mediator between customer incivility and employee outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.; Porath, C. The Cost of Bad Behavior: How Incivility Ruins Your Business and What You Can Do about It; Portfolio: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.Y.; Chen, H.L. Role of Leader–Member Exchange in the Relationship between Customer Incivility and Deviant Work Behaviors: A Moderated Mediation Model. In Reimagining: The Power of Marketing to Create Enduring Value; Society for Marketing Advances: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kalafatoğlu, Y.; Turgut, T. Individual and organizational antecedents of trait mindfulness. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2019, 16, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, F.H.; Cheng, B.S.; Kuo, C.C.; Huang, M.P. Stressors, withdrawal, and sabotage in frontline employees: The moderating effects of caring and service climates. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 755–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felblinger, D.M. Incivility and bullying in the workplace and nurses’ shame responses. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2008, 37, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.M.; Andersson, L.M.; Porath, C.L. Workplace incivility. In Counterproductive Workplace Behavior: Investigations of Actors Targets; Fox, S., Spector, P.E., Eds.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, L.; Holmvall, C.M.; O’Brien, L.E. The influence of workload and civility of treatment on the perpetration of email incivility. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 46, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Namin, B.H.; Harazneh, I.; Arasli, H.; Tunç, T. Does gender moderate the relationship between favoritism/nepotism, supervisor incivility, cynicism and workplace withdrawal: A neural network and SEM approach. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Bonn, M.A.; Han, S.J.; Lee, K.H. Workplace incivility and its effect upon restaurant frontline service employee emotions and service performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2888–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Newness, K.; Duniewicz, K. How abusive supervision affects workplace deviance: A moderated-mediation examination of aggressiveness and work-related negative affect. J. Bus. Psychol. 2016, 31, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.T.; Lin, C.P. Assessing ethical efficacy, workplace incivility, and turnover intention: A moderated-mediation model. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.M.; Lelchook, A.M.; Clark, M.A. A meta-analysis of the interrelationships between employee lateness, absenteeism, and turnover: Implications for models of withdrawal behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 678–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartline, M.D.; Witt, T.D. Individual differences among service employees: The conundrum of employee recruitment, selection, and retention. J. Relationsh. Market. 2004, 3, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odermatt, I.; König, C.J.; Kleinmann, M.; Bachmann, M.; Röder, H.; Schmitz, P. Incivility in meetings: Predictors and outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xiao, C.; He, J.; Wang, X.; Li, A. Experienced workplace incivility, anger, guilt, and family satisfaction: The double-edged effect of narcissism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 154, 109642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmon, A.F.; Pearson, J.C. Family business employees’ family communication and workplace experiences. J. Family Bus. Manag. 2013, 3, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milam, A.C.; Spitzmueller, C.; Penney, L.M. Investigating individual differences among targets of workplace incivility. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Qian, J.; Qu, Y. My Fault? Coworker Incivility and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Moderating Role of Attribution Orientation on State Guilt. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 2524–2531. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G. Role making processes within complex organizations. In Handbook of Industrial Organizational Psychology; Dunnnette, M.D., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1201–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Liden, R.C.; Maslyn, J.M. Multidimensionafity of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medler-Liraz, H. Negative affectivity and tipping: The moderating role of emotional labor strategies and leader-member exchange. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Sparrowe, R.T. An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Koo, D.W. Linking LMX, engagement, innovative behavior, and job performance in hotel employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 2, 3044–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Leiter, M.P. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory Research, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhu, Y.; Park, C. Leader–member exchange, sales performance, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment affect turnover intention. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2018, 46, 1909–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Mishra, M.; Pandey, S.K.; Ghosh, K. Can leader-member exchange social comparison elicit uncivil employee behavior? The buffering role of aggression-preventive supervisor behavior. Int. J. Conflict Manag. 2020, 32, 422–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Wang, H.; Kirkman, B.L.; Li, N. Understanding the curvilinear relationships between LMX differentiation and team coordination and performance. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 559–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.J.; Liden, R.C.; Glibkowski, B.C.; Chaudhry, A. LMX differentiation: A multilevel review and examination of its antecedents and outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.B.; Victor, B.; Bronson, J.W. The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychol. Rep. 1993, 73, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parboteeah, K.P.; Kapp, E.A. Ethical climates and workplace safety behaviors: An empirical investigation. J. Bus. Eth. 2008, 80, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Deshpande, S.P. The impact of caring climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on job performance of employees in a China’s insurance company. J. Bus. Eth. 2014, 124, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Stress, Culture, and Community. In The Psychology and Conceptualizing Stress; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative Quantitative Methods, 3rd ed.; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Daskin, M. Antecedents of extra-role customer service behaviour: Polychronicity as a moderator. Anatolia 2015, 26, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Runyan, R.C. Hospitality marketing research: Recent trends and future directions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.L.; Holmvall, C.M. The development and validation of the Incivility from Customers Scale. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.J.; Hine, D.W. Development and validation of the uncivil workplace behavior questionnaire. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandura, T.A.; Graen, G.B. Moderating effects of initial leader-member exchange status on the effects of a leadership intervention. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Occup. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Boles, J.S. Employee behavior in a service environment: A model and test of potential differences between men and women. J. Market. 1998, 62, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchel, J.O. The effect of intentions, tenure, personal, and organizational variables on managerial turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 742–751. [Google Scholar]

- Windgassen, S.; Moss-Morris, R.; Goldsmith, K.; Chalder, T. The importance of cluster analysis for enhancing clinical practice: An example from irritable bowel syndrome. J. Mental Health 2018, 27, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, C.B. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Perez, M.A.; Nunez-Anton, V. Cellwise residual analysis in two-way contingency tables. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2003, 63, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, T.M.; Schumacker, R.E. Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: Post hoc and planned comparison procedures. J. Exp. Educ. 1995, 64, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, S.W.; Hung, W.T.; Chiu, C.K.; Lin, C.P.; Hsu, Y.C. To quit or not to quit Understanding turnover intention from the perspective of ethical climate. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, M.A.; Boswell, W.R.; Roehling, M.V.; Boudreau, J.W. An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, I.; Waseem, M.; Sikander, S.; Rizwan, M. The relationship of turnover intention with job satisfaction, job performance, leader member exchange, emotional intelligence and organizational commitment. Int. J. Learn. Dev. 2014, 4, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.A.; Ritter, K.J. Applying adaptation theory to understand experienced incivility processes: Testing the repeated exposure hypothesis. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.J.; Troth, A. Emotional intelligence and leader member exchange: The relationship with employee turnover intentions and job satisfaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2011, 32, 260–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chai, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, T. How workplace incivility influences job performance: The role of image outcome expectations. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 57, 445–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, P.M.; De Cooman, R.; Mol, S.T. Dynamics of psychological contracts with work engagement and turnover intention: The influence of organizational tenure. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y. Can “bad” stressors spark “good” behaviors in frontline employees? Incorporating motivation and emotion. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 33, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n = 291) | Percentage (100%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 98 | 33.7 |

| Female | 193 | 66.3 | |

| Tenure | 6–11 months | 65 | 22.3 |

| 1–3 years | 132 | 45.4 | |

| 4–5 years | 50 | 17.2 | |

| More than 5 years | 44 | 15.1 | |

| Industry | Hotel | 190 | 65.3 |

| Restaurant | 101 | 34.7 | |

| Supervising position | Yes | 74 | 25.4 |

| No | 217 | 74.6 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Customer incivility | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Coworker incivility | 0.29 ** | - | |||||||||

| 3. Emotional exhaustion | 0.28 ** | 0.28 ** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Job performance | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.06 | - | |||||||

| 5. Turnover intention | 0.08 | 0.17 ** | 0.52 ** | −0.02 | - | ||||||

| 6. LMX quality | −0.09 | −0.16 ** | −0.39 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.49 ** | - | |||||

| 7. Caring climate | −0.13 * | −0.25 ** | −0.36 ** | 0.06 | −0.45 ** | 0.53 ** | - | ||||

| 8. Gender | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.13 * | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.12 * | −0.12 * | - | |||

| 9. Tenure | 0.19 ** | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.14 * | −0.002 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.06 | - | ||

| 10. Industry | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.07 | −0.17 ** | 0.08 | 0.03 | - | |

| 11. Supervising position | −0.06 | −0.13 * | −0.05 | −0.24 ** | −0.09 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.25 ** | −0.04 | - |

| Variables | Clusters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Independent Employees | (2) Integrated Employees | (3) Disintegrated Employees | |

| Customer incivility | Low | Medium | High |

| Coworker incivility | Low | Medium | High |

| Emotional exhaustion | Low | Medium | High |

| Job performance | Low | High | Medium |

| Turnover intention | Medium | Low | High |

| LMX quality | Medium | High | Low |

| Caring climate | Medium | High | Low |

| Personal Characteristics and Working Conditions | Clusters | Overall (n = 291) | Between Clusters | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Independent Employees (n = 108) | (2) Integrated Employees (n = 80) | (3) Disintegrated Employees (n = 103) | Post Hoc Tests (Bonferroni Correction) | |||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | Mean (SD) | χ2 | p | p | p | p | |

| Gender (M/SD) | (0.59/0.49) | (0.61/0.49) | (0.78/0.42) | 0.66 (0.47) | 16.95 | *** | *** | 0.81 | *** | |||

| Male | 44 | 40.70 | 31 | 38.75 | 23 | 22.30 | ||||||

| Female | 64 | 59.30 | 49 | 61.25 | 80 | 77.70 | ||||||

| Tenure | (1.75/0.77) | (2.78/0.90) | (2.37/0.96) | 2.25 (0.97) | 44.26 | *** | ||||||

| 6–11 months | 46 | 42.60 | 2 | 2.50 | 17 | 16.50 | *** | *** | 0.58 | |||

| 1–3 years | 46 | 42.60 | 37 | 46.25 | 49 | 47.60 | 0.63 | 0.18 | 0.33 | |||

| 4–5 years | 13 | 12.00 | 18 | 22.50 | 19 | 18.45 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.74 | |||

| More than 5 years | 3 | 2.80 | 23 | 28.75 | 18 | 17.50 | *** | *** | 0.71 | |||

| Industry | (1.44/0.50) | (1.14/0.35) | (1.41/0.49) | 1.35 (0.48) | 9.00 | ** | ** | 0.49 | ** | |||

| Hotel | 60 | 55.60 | 69 | 86.25 | 61 | 59.20 | ||||||

| Restaurant | 48 | 44.40 | 11 | 13.75 | 42 | 40.80 | ||||||

| Supervising position | (1.91/0.29) | (1.55/0.50) | (1.73/0.45) | 1.75 (0.44) | 100.20 | *** | *** | *** | 0.10 | |||

| Yes | 10 | 9.25 | 36 | 45.00 | 28 | 27.20 | ||||||

| No | 98 | 90.75 | 44 | 55.00 | 75 | 72.80 | ||||||

| Main Variables | Clusters | Overall (n = 291) | Between Clusters | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Independent Employees (n = 108) | (2) Integrated Employees (n = 80) | (3) Disintegrated Employees (n = 103) | Post Hoc Tests (Tukey) | |||||||

| 1 to 2 | 1 to 3 | 2 to 3 | ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M (SD) | p | p | p | |

| Customer incivility | 2.09 | 0.57 | 2.86 | 0.63 | 3.03 | 0.72 | 2.64 (0.77) | *** | *** | 0.20 |

| Coworker incivility | 1.38 | 0.41 | 1.55 | 0.48 | 1.90 | 0.58 | 1.61 (0.54) | 0.06 | *** | *** |

| Emotional exhaustion | 2.20 | 0.74 | 2.27 | 0.75 | 3.58 | 0.83 | 2.71 (1.01) | 0.83 | *** | *** |

| Job performance | 3.06 | 0.68 | 3.83 | 0.61 | 3.46 | 0.62 | 3.41 (0.71) | *** | *** | *** |

| Turnover intention | 2.80 | 0.88 | 2.43 | 0.70 | 3.84 | 0.75 | 3.06 (0.98) | ** | *** | *** |

| LMX quality | 3.70 | 0.60 | 4.34 | 0.58 | 3.12 | 0.66 | 3.67 (0.78) | *** | *** | *** |

| Caring climate | 3.71 | 0.76 | 3.96 | 0.65 | 2.76 | 0.76 | 3.44 (0.89) | ** | *** | *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Namin, B.H.; Marnburg, E.; Bakkevig Dagsland, Å.H. Frontline Service Employees’ Profiles: Exploring Individual Differences in Perceptions of and Reactions to Workplace Incivility. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12030076

Namin BH, Marnburg E, Bakkevig Dagsland ÅH. Frontline Service Employees’ Profiles: Exploring Individual Differences in Perceptions of and Reactions to Workplace Incivility. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(3):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12030076

Chicago/Turabian StyleNamin, Boshra H., Einar Marnburg, and Åse Helene Bakkevig Dagsland. 2022. "Frontline Service Employees’ Profiles: Exploring Individual Differences in Perceptions of and Reactions to Workplace Incivility" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 3: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12030076

APA StyleNamin, B. H., Marnburg, E., & Bakkevig Dagsland, Å. H. (2022). Frontline Service Employees’ Profiles: Exploring Individual Differences in Perceptions of and Reactions to Workplace Incivility. Behavioral Sciences, 12(3), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12030076