The Relationship between Personality Traits and COVID-19 Anxiety: A Mediating Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Big Five Personality Traits and COVID-19 Anxiety

1.1.2. Big Five Personality Traits and Sleep Quality

1.1.3. Sleep Quality and COVID-19 Anxiety

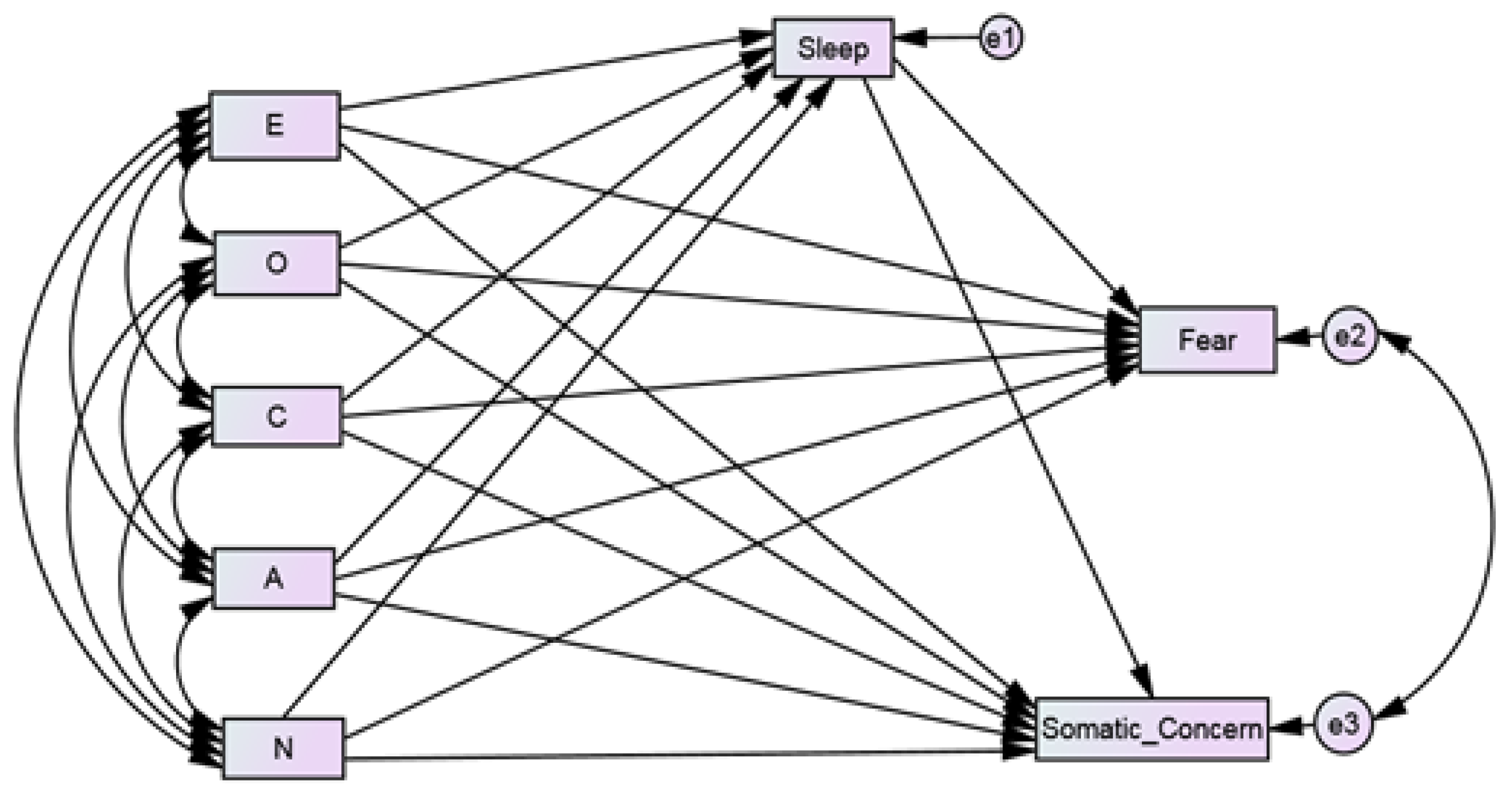

1.2. The Present Study

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design, Data Collection, and Procedures

2.2. Measures for the Study

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Information

2.2.2. Big Five Inventory-10(BFI-10)

2.2.3. COVID-19 Pandemic Anxiety Scale (COVID-19 PAS)

2.2.4. Sleep Quality Scale (SQS)

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

3.2. Testing for Common Method Bias

3.3. Descriptive Analysis

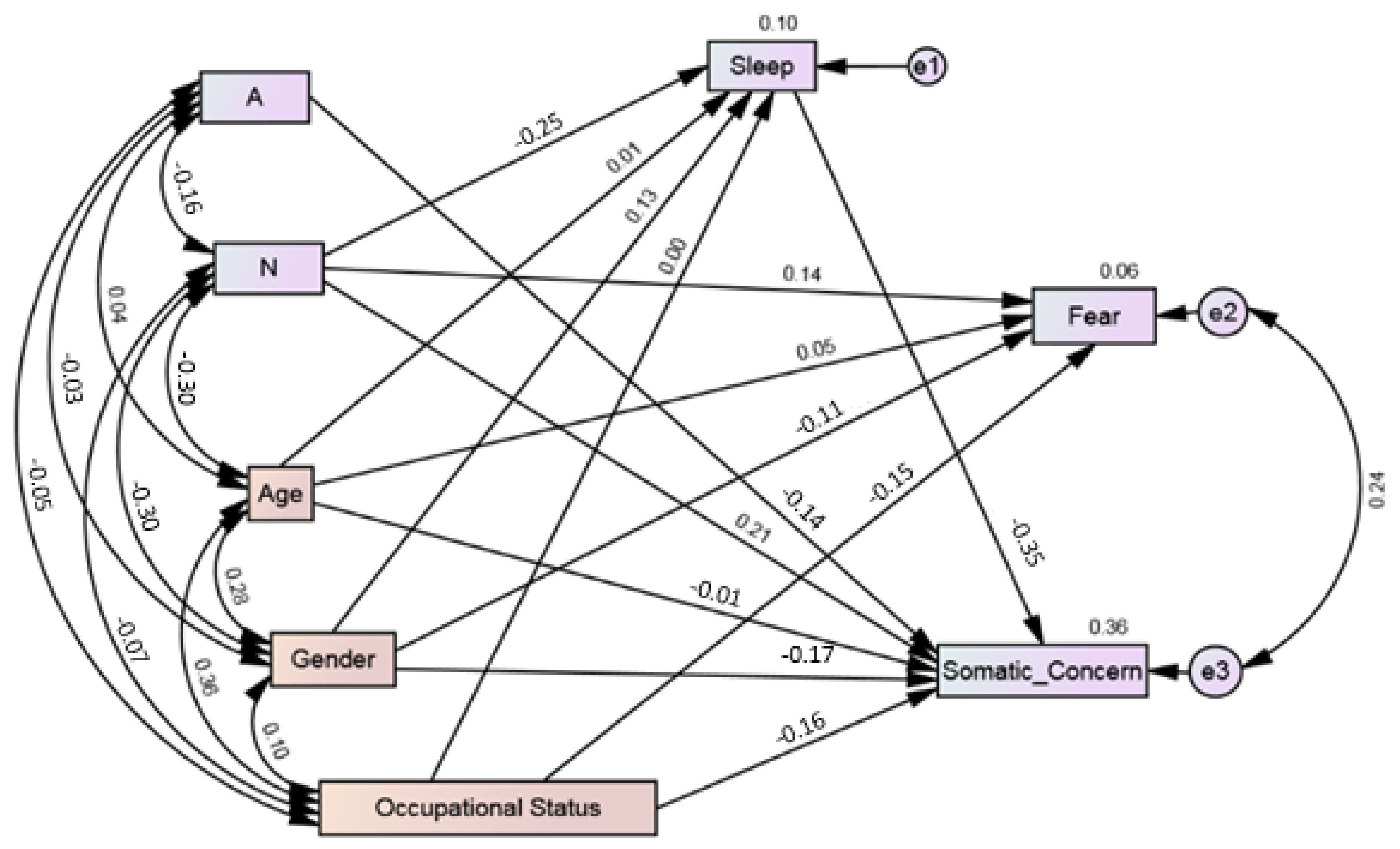

3.4. Path Analysis: Direct and Indirect Associations

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, V.V.; Tankha, G.; Seth, S.; Timple, T.S. Construction and preliminary validation of the COVID-19 Pandemic Anxiety Scale. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 1, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Guo, L.; Yu, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshar, H.; Roohafza, H.R.; Keshteli, A.H.; Mazaheri, M.; Feizi, A.; Adibi, P. The association of personality traits and coping styles according to stress level. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2015, 20, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Personality in Adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory Perspective, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Komulainen, E.; Meskanen, K.; Lipsanen, J.; Lahti, J.M.; Jylha, P.; Melartin, T.; Wichers, M.; Isometsa, E.; Ekelund, J. The effect of personality on daily life emotional processes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranieri, J.; Guerra, F.; Cilli, E.; Caiazza, I.; Gentili, N.; Ripani, B.; Di Giacomo, D. Buffering effect of e-learning on Generation Z undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study during the second COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikcevic, A.V.; Marino, C.; Kolubinski, D.C.; Leach, D.; Spada, M.M. Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 15, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, M. Neuroticism as a marker of vulnerability to COVID-19 infection. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 710–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokrkon, A.; Nicoladis, E. How personality traits of neuroticism and extroversion predict the effects of the COVID-19 on the mental health of Canadians. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 14, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotov, R.; Gamez, W.; Schmidt, F.; Watson, D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 768–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otonari, J.; Nagano, J.; Morita, M.; Budhathoki, S.; Tashiro, N.; Toyomura, K.; Kono, S.; Imai, K.; Ohnaka, K.; Takayanagi, R. Neuroticism and extraversion personality traits, health behaviours, and subjective well-being: The Fukuoka Study (Japan). Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K.; Judge, T.A. Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next? Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2001, 9, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.L.; Zmora, R.; Finlay, J.M.; Jutkowitz, E.; Gaugler, J.E. Do big five personality traits moderate the effects of stressful life events on health trajectories? Evidence from the health and retirement study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Jobe, M.C.; Mathis, A.A.; Gibbons, J.A. Incremental validity of coronaphobia: Coronavirus anxiety explains depression, generalized anxiety, and death anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, F.; Wei, C.; Jia, Y.; Shang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Personality and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic: Testing the mediating role of perceived threat and efficacy. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 168, 110351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroencke, L.; Geukes, K.; Utesch, T.; Kuper, N.; Back, M.D. Neuroticism and emotional risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Pers. 2020, 89, 104038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modersitzki, N.; Phan, L.V.; Kuper, N.; Rauthmann, J.F. Who is impacted? Personality predicts individual differences in psychological consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2021, 12, 1110–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengual, N.P.; Aragones-Barbera, I.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Moliner-Albero, A.R. The relationship of fear of death between neuroticism and anxiety during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 648498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, I.; de Lima, M.P.; Matos, M.; Figueiredo, C. Personality and subjective well-being: What hides behind global analyses? Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 105, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, A.; Graziano, W.G.; Branch, S.E.; Habashi, M.M.; Ngambeki, I.; Evangelou, D. Person and thing orientations: Psychological correlates and predictive utility. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013, 4, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wijngaards, I.; de Zilwa, S.C.M.; Burger, M.J. Extraversion moderates the relationship between the stringency of COVID-19 protective measures and depressive symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 568907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.F.; Vgontzas, A.N. Insomnia and its impact on physical and mental health. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2013, 15, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Wu, C.; Gan, Y.; Qu, X.; Lu, Z. Insomnia and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Potvin, O.; Lorrain, D.; Belleville, G.; Grenier, S.; Préville, M. Subjective sleep characteristics associated with anxiety and depression in older adults: A population-based study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofi, F.; Cesari, F.; Casini, A.; Macchi, C.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F. Insomnia and risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S.; Magee, C.A.; Vella, S.A. Personality, hedonic balance and the quality and quantity of sleep in adulthood. Psychol. Health 2016, 31, 1091–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellini, N.; Duggan, K.A.; Sarlo, M. Perceived sleep quality: The interplay of neuroticism, affect, and hyperarousal. Sleep Health 2017, 3, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duggan, K.A.; Friedman, H.S.; McDevitt, E.A.; Mednick, S.C. Personality and healthy sleep: The importance of conscientiousness and neuroticism. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, E.K.; Watson, D. General and specific traits of personality and their relation to sleep and academic performance. J. Pers. 2002, 70, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hintsanen, M.; Puttonen, S.; Smith, K.; Tornroos, M.; Jokela, M.; Pulkki-Raback, L.; Hintsa, T.; Merjonen, P.; Dwyer, T.; Raitakari, O.T.; et al. Five-factor personality traits and sleep: Evidence from two population-based cohort studies. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, V.; Peck, K.; Mallya, S.; Lupien, S.J.; Fiocco, A.J. Subjective sleep quality as a possible mediator in the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms in middle-aged adults. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.G.; Moroz, T.L. Personality vulnerability to stress-related sleep disruption: Pathways to adverse mental and physical health outcomes. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Cho, J.; Chang, Y.; Ryu, S.; Shin, H.; Kim, H.L. Association between personality traits and sleep quality in young Korean women. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.R.; Bayard, S.; Križan, Z.; Terracciano, A. Personality and sleep quality: Evidence from four prospective studies. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkovic, A.; Vukasovic, T.; Bratko, D. Sleep duration and personality in Croatian twins. J. Sleep Res. 2014, 23, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cankurtaran, D.; Tezel, N.; Ercan, B.; Yildiz, S.Y.; Akyuz, E.U. The effects of COVID-19 fear and anxiety on symptom severity, sleep quality, and mood in patients with fibromyalgia: A pilot study. Adv. Rheumatol. 2021, 61, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Zhao, R.; Xiao, Q.; Zhuo, Y.; Yu, J.; Meng, X. The effect of mental health on sleep quality of frontline medical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak in China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, B.; Bylsma, L.M.; Morris, B.H.; Rottenberg, J. Poor reported sleep quality predicts low positive affect in daily life among healthy and mood-disordered persons. J. Sleep Res. 2010, 19, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.G.; Reider, B.D.; Whiting, A.B.; Prichard, J.R. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrae, C.S.; McNamara, J.P.; Rowe, M.A.; Dzierzewski, J.M.; Dirk, J.; Marsiske, M.; Craggs, J.G. Sleep and affect in older adults: Using multilevel modeling to examine daily associations. J. Sleep Res. 2008, 17, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nyer, M.; Farabaugh, A.; Fehling, K.; Soskin, D.; Holt, D.; Papakostas, G.I.; Pedrelli, P.; Fava, M.; Pisoni, A.; Vitolo, O.; et al. Relationship between sleep disturbance and depression, anxiety, and functioning in college students. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Hardway, C. Daily variation in adolescents’ sleep, activities, and psychological well-being. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneita, Y.; Yokoyama, E.; Harano, S.; Tamaki, T.; Suzuki, H.; Munezawa, T.; Nakajima, H.; Asai, T.; Ohida, T. Associations between sleep disturbance and mental health status: A longitudinal study of Japanese junior high school students. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A.M.; Reitz, E.; Dekovic, M.; van den Wittenboer, G.L.; Stoel, R.D. Longitudinal relations between sleep quality, time in bed and adolescent problem behaviour. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Zan, M.C.H.; Cho, M.J.; Fenton, J.I.; Hsiao, P.Y.; Hsiao, R.; Keaver, L.; Lai, C.C.; Lee, H.; Ludy, M.J.; et al. Increased resilience weakens the relationship between perceived stress and anxiety on sleep quality: A moderated mediation analysis of higher education students from 7 countries. Clocks Sleep 2020, 2, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Webb, T.L.; Martyn-St James, M.; Rowse, G.; Weich, S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 60, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltz, J.S.; Rogge, R.D.; Pugach, C.P.; Strang, K. Bidirectional associations between sleep and anxiety symptoms in emerging adults in a residential college setting. Emerg. Adulthood 2017, 5, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, P.K.; Roberts, R.M.; Harris, J.K. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep 2013, 36, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zung, W.W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 1971, 12, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J. Res. Pers. 2007, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.J.; John, O.P. Short and extra-short forms of the Big Five Inventory–2: The BFI-2-S and BFI-2-XS. J. Res. Pers. 2017, 68, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.V.; Tankha, G.; Shelly; Seth, S.; Apeksha; Timple, T.S. COVID-19 Pandemic Anxiety Scale. [PsycTESTS. Database record] 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353701992_COVID_19_Pandemic_Anxiety_Scale_COVID-19_PAS-10 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Snyder, E.; Cai, B.; DeMuro, C.; Morrison, M.F.; Ball, W.A. New single-item Sleep Quality Scale: Results of psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic primary insomnia and depression. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mardia, K.V. Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika 1970, 57, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Wu, E.J.C. EQS 6.1 for Windows User’s Guide; Multivariate Software: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nevitt, J.; Hancock, G.R. Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2001, 8, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Stine, R.A. Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| S. No. | Socio-Demographic Variable | N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gender | Females | 183 | 61.80 |

| Males | 113 | 38.20 | ||

| 2. | Marital Status | Married | 149 | 50.34 |

| Unmarried | 138 | 46.62 | ||

| Others | 9 | 3.04 | ||

| 3. | Education | Higher secondary | 74 | 25.00 |

| Undergraduate | 7 | 2.360 | ||

| Graduate | 103 | 34.80 | ||

| Postgraduate | 100 | 33.78 | ||

| PhD | 12 | 4.05 | ||

| 4. | Occupational Status | Not employed | 168 | 56.76 |

| Employed | 129 | 43.24 |

| Total | Females | Males | t | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (N = 296) | (n = 183) | (n = 113) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Extraversion | 6.35 | 2.23 | 6.17 | 2.41 | 6.65 | 1.88 | −1.77 | 0.078 |

| Conscientiousness | 7.16 | 1.73 | 7.02 | 1.65 | 7.39 | 1.82 | −1.79 | 0.075 |

| Neuroticism | 5.95 | 2.13 | 6.44 | 2.17 | 5.15 | 1.81 | 5.30 | 0.000 |

| Openness | 6.79 | 1.56 | 6.79 | 1.63 | 6.79 | 1.43 | 0.00 | 0.997 |

| Agreeableness | 7.76 | 1.71 | 7.80 | 1.71 | 7.70 | 1.70 | 0.51 | 0.611 |

| Sleep | 6.80 | 2.34 | 6.43 | 2.45 | 7.42 | 2.01 | −3.60 | 0.000 |

| Fear | 5.90 | 3.62 | 6.33 | 3.58 | 5.20 | 3.59 | 2.62 | 0.009 |

| Somatic Concern | 2.35 | 2.54 | 2.99 | 2.79 | 1.32 | 1.61 | 5.80 | 0.000 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion (1) | 1 | |||||||

| Conscientiousness (2) | 0.243 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Neuroticism (3) | −0.252 ** | −0.327 ** | 1 | |||||

| Openness (4) | −0.002 | −0.067 | 0.009 | 1 | ||||

| Agreeableness (5) | 0.186 ** | 0.053 | −0.163 ** | 0.045 | 1 | |||

| Sleep (6) | 0.146 * | 0.146 * | −0.295 ** | 0.052 | 0.083 | 1 | ||

| Fear (7) | −0.046 | −0.074 | 0.171 ** | −0.021 | −0.116 * | −0.091 | 1 | |

| Somatic Concern (8) | −0.244 ** | −0.268 ** | 0.401 ** | −0.076 | −0.208 ** | −0.470 ** | 0.318 ** | 1 |

| Model Pathways | Direct | Indirect via Sleep | Total Effects | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| β | Lower | Upper | p | β | Lower | Upper | p | β | Lower | Upper | p | |

| E → F | 0.013 | −0.096 | 0.136 | 0.747 | −0.001 | −0.022 | 0.007 | 0.496 | 0.012 | −0.102 | 0.130 | 0.791 |

| O → F | −0.022 | −0.157 | 0.088 | 0.627 | −0.001 | −0.018 | 0.006 | 0.451 | −0.023 | −0.163 | 0.088 | 0.608 |

| C→ F | −0.014 | −0.130 | 0.117 | 0.845 | −0.001 | −0.016 | 0.007 | 0.561 | −0.016 | −0.130 | 0.109 | 0.813 |

| A→ F | −0.109 | −0.213 | 0.011 | 0.071 | −0.001 | −0.017 | 0.005 | 0.546 | −0.110 | −0.215 | 0.010 | 0.065 |

| N → F | 0.115 | −0.010 | 0.232 | 0.081 | 0.005 | −0.028 | 0.036 | 0.723 | 0.121 | −0.003 | 0.236 | 0.055 |

| E → SC | −0.086 | −0.181 | 0.021 | 0.095 | −0.020 | −0.072 | 0.019 | 0.299 | −0.106 | −0.209 | 0.009 | 0.068 |

| O → SC | −0.068 | −0.172 | 0.023 | 0.130 | −0.019 | −0.060 | 0.020 | 0.340 | 0.086 | −0.194 | 0.011 | 0.083 |

| C→ SC | −0.109 | −0.214 | 0.007 | 0.062 | −0.017 | −0.064 | 0.027 | 0.390 | −0.126 | −0.234 | −0.011 | 0.029 |

| A → SC | −0.142 | −0.245 | −0.050 | 0.004 | −0.012 | −0.049 | 0.024 | 0.541 | −0.154 | −0.262 | −0.051 | 003 |

| N → SC | 0.167 | 0.057 | 0.289 | 0.007 | 0.075 | −0.038 | 0.124 | 0.002 | 0.243 | 0.131 | 0.361 | 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, V.V.; Tankha, G. The Relationship between Personality Traits and COVID-19 Anxiety: A Mediating Model. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12020024

Kumar VV, Tankha G. The Relationship between Personality Traits and COVID-19 Anxiety: A Mediating Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, V. Vineeth, and Geetika Tankha. 2022. "The Relationship between Personality Traits and COVID-19 Anxiety: A Mediating Model" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12020024

APA StyleKumar, V. V., & Tankha, G. (2022). The Relationship between Personality Traits and COVID-19 Anxiety: A Mediating Model. Behavioral Sciences, 12(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12020024