Indulging in Smartphones in Times of Stress: A Moderated Mediation Model of Experiential Avoidance and Trait Mindfulness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Perceived Stress and Problematic Smartphone Use

1.2. Experiential Avoidance as a Mediator

1.3. Trait Mindfulness as a Moderator

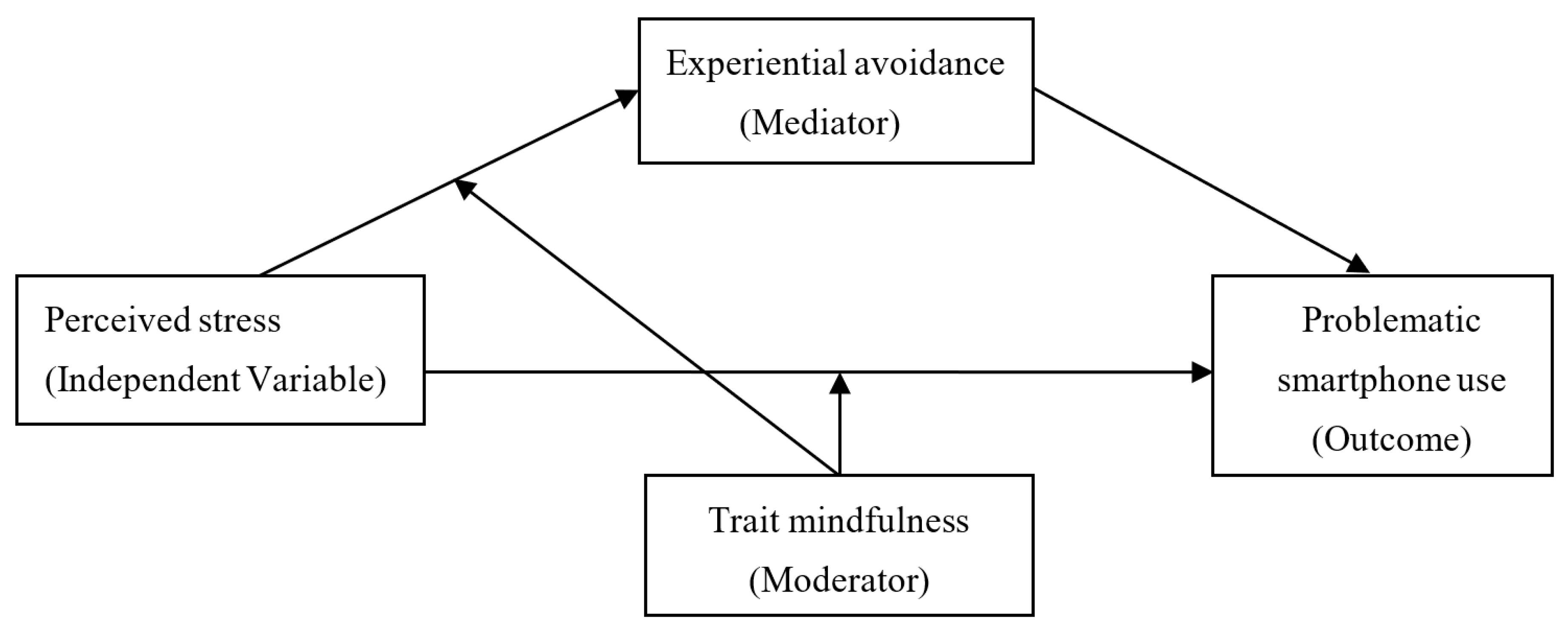

1.4. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Stress

2.2.2. Problematic Smartphone Use

2.2.3. Experiential Avoidance

2.2.4. Trait Mindfulness

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Testing of Common Method Biases

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

3.3. Testing for Mediation Effect

3.4. Testing for Moderated Mediation

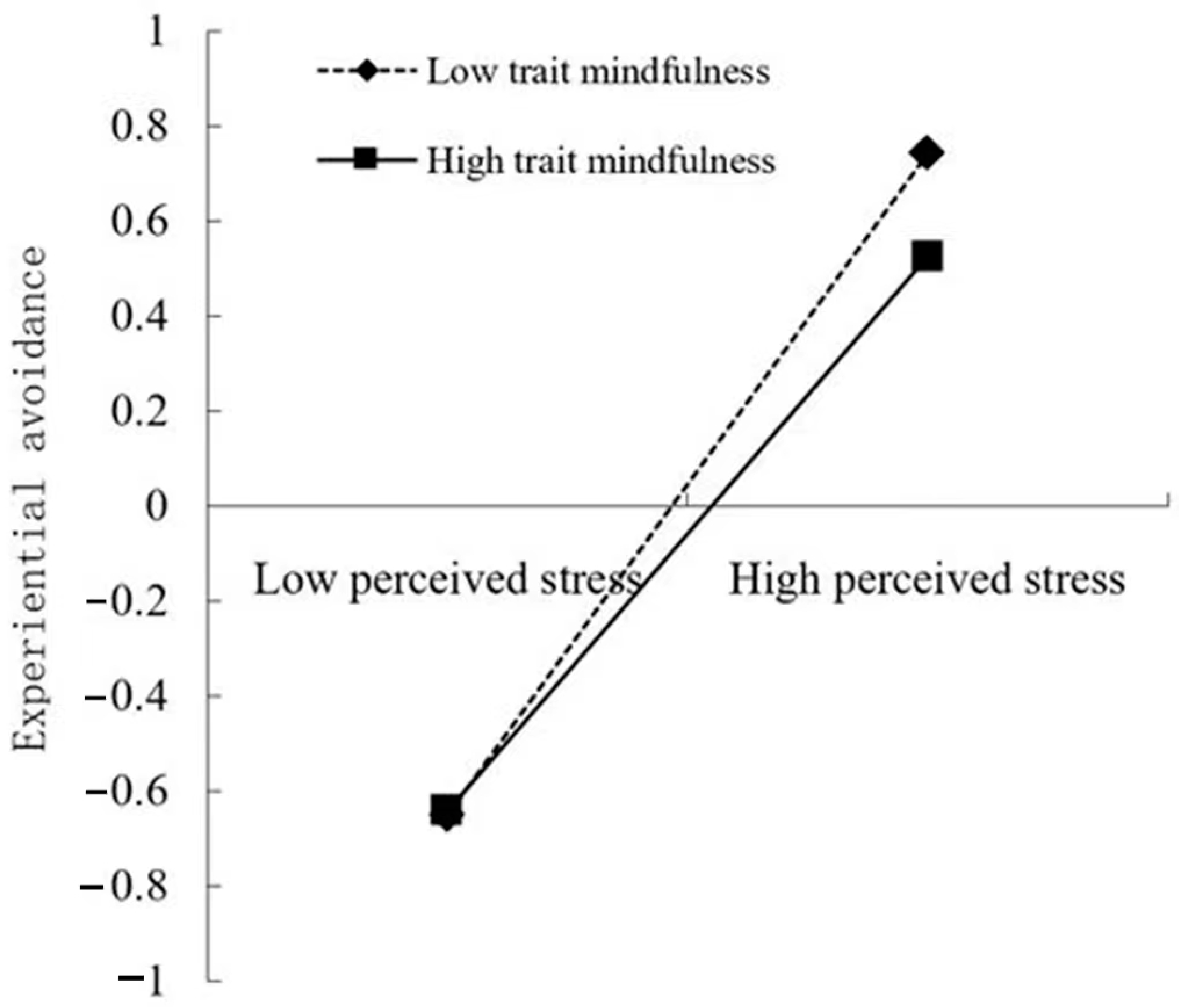

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediating Role of Experiential Avoidance

4.2. The Moderating Role of Trait Mindfulness

5. Strength and Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 50th China Statistical Report on Internet Development. 2022. Available online: https://www.chinajusticeobserver.com/a/china-releases-50th-statistical-report-on-domestic-internet-development (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Le Busque, B.; Mingoia, J. Getting social: Postgraduate students use of social media. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensmann, S.; Whiteside, A.L. “It Helped to Know I Wasn’t Alone”: Exploring Student Satisfaction in an Online Community with a Gamified, Social Media-Like Instructional Approach. Online Learn. 2022, 26, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.Q.; Cheng, J.L.; Li, Y.Y.; Yang, X.Q.; Zheng, J.W.; Chang, X.W.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L.; Sun, Y.; et al. Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 92, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermand, M.; Benyamina, A.; Donnadieu-Rigole, H.; Petillion, A.; Amirouche, A.; Romeo, B.; Karila, L. Addictive Use of Online Sexual Activities and its Comorbidities: A Systematic Review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2020, 7, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.P.; Wang, P.C.; Lei, L. Trait anger and cyberbullying among young adults: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and moral identity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, L.; You, X.Q.; Huang, J.; Yang, R.J. Who overuses Smartphones? Roles of virtues and parenting style in Smartphone addiction among Chinese college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.F.; Guan, J.L.; Chen, H.H.; Huang, S.J.; Liu, B.J.; Chen, X.H. The Relationship between Trait Fear of Missing Out and Smartphone Addiction in College Students: A Mediating and Moderating Model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 30, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Rees, P.; Wildridge, B.; Kalk, N.J.; Carter, B.J.B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: A systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Billieux, J.; Maurage, P.; Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Can Disordered Mobile Phone Use Be Considered a Behavioral Addiction? An Update on Current Evidence and a Comprehensive Model for Future Research. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2015, 2, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, Y.H.; Chian, C.L.; Lin, P.H.; Chang, L.R.; Ko, C.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Lin, S.H. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Smartphone Addiction. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, M.; Hawi, N.S. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratan, Z.A.; Parrish, A.M.; Bin Zaman, S.; Alotaibi, M.S.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Smartphone Addiction and Associated Health Outcomes in Adult Populations: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawi, N.S.; Samaha, M. Relationships among smartphone addiction, anxiety, and family relations. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2017, 36, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, K.; Akgonul, M.; Akpinar, A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.G.; Park, J.; Kim, H.T.; Pan, Z.H.; Lee, Y.; McIntyre, R.S. The relationship between smartphone addiction and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity in South Korean adolescents. Ann. Gen. Psychiatr. 2019, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanković, M.; Nešić, M.; Čičević, S.; Shi, Z. Association of smartphone use with depression, anxiety, stress, sleep quality, and internet addiction. Empirical evidence from a smartphone application. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 168, 110342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volungis, A.M.; Kalpidou, M.; Popores, C.; Joyce, M. Smartphone Addiction and Its Relationship with Indices of Social-Emotional Distress and Personality. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 1209–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.J.; Park, J.W. The Influence of Stress on Internet Addiction: Mediating Effects of Self-Control and Mindfulness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.H.; Ma, Y.T.; Zhong, Q.S. The Relationship Between Adolescents’ Stress and Internet Addiction: A Mediated-Moderation Model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.L.; Wang, H.Z.; Hu, T.Q.; Gentile, D.A.; Gaskin, J.; Wang, J.L. The relationship between perceived stress and problematic social networking site use among Chinese college students. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.B.; Ni, X.L.; Niu, G.F. Perceived Stress and Short-Form Video Application Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 747656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Building on the foundation of general strain theory: Specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2001, 38, 319–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Zhang, D.J.; Yang, X.J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Fan, C.Y.; Zhou, Z.K. Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction in Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, H.L.; Zhang, B.; Mao, H.L.; Hu, R.T.; Jiang, H.B. Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction among college students during the 2019 coronavirus disease: The mediating roles of rumination and the moderating role of self-control. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 185, 111222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Levin, M.E.; Plumb-Vilardaga, J.; Villatte, J.L.; Pistorello, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Contextual Behavioral Science: Examining the Progress of a Distinctive Model of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy. Behav. Ther. 2013, 44, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roemer, L.; Orsillo, S.M. An acceptance-based behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. In Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fifth Edition: A Step-by-Step Treatment Manual, 5th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 206–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Wilson, K.G.; Gifford, E.V.; Follette, V.M.; Strosahl, K. Experiential avoidance and behaviour disorder: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 1152–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochefort, C.; Baldwin, A.S.; Chmielewski, M. Experiential Avoidance: An Examination of the Construct Validity of the AAQ-II and MEAQ. Behav. Ther. 2018, 49, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walser, R.D.; Hayes, S.C. Acceptance and trauma survivors: Applied issues and problems. In Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies for Trauma; Follette, V.M., Ruzek, J.I., Abueg, F.R., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 256–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen, J.R. Short-term pain for long-term gain: The role of experiential avoidance in the relation between anxiety sensitivity and emotional distress. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015, 30, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.E.; MacLane, C.; Daflos, S.; Seeley, J.; Hayes, S.C.; Biglan, A.; Pistorello, J. Examining psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic process across psychological disorders. J. Contextual. Behav. Sci. 2014, 3, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kingston, J.; Clarke, S.; Remington, B. Experiential Avoidance and Problem Behavior: A Mediational Analysis. Behav. Modif. 2010, 34, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmquist, J.; Shorey, R.C.; Anderson, S.; Stuart, G.L. Experiential Avoidance and Bulimic Symptoms among Men in Residential Treatment for Substance Use Disorders: A Preliminary Examination. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2018, 50, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckner, J.D.; Zvolensky, M.J.; Farris, S.G.; Hogan, J. Social Anxiety and Coping Motives for Cannabis Use: The Impact of Experiential Avoidance. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Oliva, C.; Piqueras, J.A. Experiential Avoidance and Technological Addictions in Adolescents. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiz-Ruano, A.M.; Lopez-Salmeron, M.D.; Puga, J.L. Experiential avoidance and excessive smartphone use: A Bayesian approach. Adicciones 2020, 32, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuru, T.; Celenk, S. The Relationship Among Anxiety, Depression, and Problematic Smartphone Use in University Students: The Mediating Effect of Psychological Inflexibility. Alpha Psychiatry 2021, 22, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorday, J.Y.; Bardeen, J.R. Problematic Smartphone Use Influences the Relationship Between Experiential Avoidance and Anxiety. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2022, 25, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.P.; Yen, C.F.; Liu, T.L. Predicting Effects of Psychological Inflexibility/Experiential Avoidance and Stress Coping Strategies for Internet Addiction, Significant Depression, and Suicidality in College Students: A Prospective Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wersebe, H.; Lieb, R.; Meyer, A.H.; Hofer, P.; Gloster, A.T. The link between stress, well-being, and psychological flexibility during an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy self-help intervention. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2018, 18, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Xie, J.Y.; Owusua, T.; Chen, Z.H.; Wang, J.G.; Qin, C.X.; He, Q.N. Is psychological flexibility a mediator between perceived stress and general anxiety or depression among suspected patients of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19)? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2021, 183, 111132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Kanekar, A.; Batra, K.; Hayes, T.; Lakhan, R. Introspective Meditation before Seeking Pleasurable Activities as a Stress Reduction Tool among College Students: A Multi-Theory Model-Based Pilot Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.Y.; Chen, Y.H. Effect of stress perception of COVID-19 and psychological flexibility on depression in college students: A moderated mediation model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 28, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkush, F.T.; Kachooei, M.; Vahidi, E. The relationship between shame and internet addiction among university students: The mediating role of experiential avoidance. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2022, 27, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garey, L.; Farris, S.G.; Schmidt, N.B.; Zvolensky, M.J. The role of smoking-specific experiential avoidance in the relation between perceived stress and tobacco dependence, perceived barriers to cessation, and problems during quit attempts among treatment-seeking smokers. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2016, 5, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go. There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Piatkus: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.A.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, J.T.; Braun, S.E.; Freeman, S.P.; McDaniel, M.A.; Brown, K.W. Meta-Analytic Evidence for Effects of Mindfulness Training on Dimensions of Self-Reported Dispositional Mindfulness. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomlinson, E.R.; Yousaf, O.; Vitterso, A.D.; Jones, L. Dispositional Mindfulness and Psychological Health: A Systematic Review. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.J.; Zhou, Z.K.; Liu, Q.Q.; Fan, C.Y. Mobile Phone Addiction and Adolescents’ Anxiety and Depression: The Moderating Role of Mindfulness. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.L.; Qian, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.P.; Zhang, Y.H. Mindfulness and cell phone dependence: The mediating role of social adaptation. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2021, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, I. Relationships Between Early Maladaptive Schemas and Smartphone Addiction: The Moderating Role of Mindfulness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.K.; Ding, J.E.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.F.; Liu, M.B.; Fu, H. A pilot study of a group mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for smartphone addiction among university students. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.C.Y.; Lee, R.L.T. Effects of a group mindfulness-based cognitive programme on smartphone addictive symptoms and resilience among adolescents: Study protocol of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parsons, E.M.; Dreyer-Oren, S.E.; Magee, J.C.; Clerkin, E.M. Evaluating the indirect effects of trait mindfulness facets on state tripartite components through state rumination and state experiential avoidance. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2019, 207, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Ramirez-Valles, J.; Maton, K.I. Resilience among urban African American male adolescents: A study of the protective effects of sociopolitical control on their mental health. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1999, 27, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Yang, X.J.; Hu, Y.T.; Zhang, C.Y.; Nie, Y.G. How and when is family dysfunction associated with adolescent mobile phone addiction? Testing a moderated mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 111, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, H.C.; Overall, N.C. Dispositional mindfulness attenuates the link between daily stress and depressed mood. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 35, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Sampedro, A. Does the acting with awareness trait of mindfulness buffer the predictive association between stressors and psychological symptoms in adolescents? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017, 105, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. Psychological flexibility and COVID-19 burnout in Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2022, 24, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, G.X.; Lei, G.H.; Xiao, Q.; Cao, X.C.; Bian, Y.R.; Xie, S.M.; et al. Psychological stress of medical staffs during outbreak of COVID-19 and adjustment strategy. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1962–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, G. Perceived stress in a prob-ability sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health; Spacapan, S., Oska-mp, S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Tian, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S. Reliability and validity of the perceived stress scale short form (PSS-10) for Chinese college students. Psychol. Explor. 2021, 41, 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Luk, T.T.; Wang, M.P.; Shen, C.; Wan, A.; Chau, P.H.; Oliffe, J.; Viswanath, K.; Chan, S.S.; Lam, T.H. Short version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale in Chinese adults: Psychometric properties, sociodemographic, and health behavioral correlates. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, J.; Ji, Y.; Zhu, Z.H. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the acceptance and action questionnaire-second edition (AAQ-I) in college students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2013, 27, 873–877. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, T.; Chen, C.; Chen, S. Validation of a Chinese version of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire and development of a short form based on item response theory. Curr. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; McGonagle, A. Four Research Designs and a Comprehensive Analysis Strategy for Investigating Common Method Variance with Self-Report Measures Using Latent Variables. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 31, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.C.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Jiang, H.B.; Cheng, Y. Global Prevalence of Mobile Phone Addiction: A Meta-Analysis. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2021, 19, 802–808. [Google Scholar]

- Chóliz, M.J.A. Mobile phone addiction: A point of issue. Addiction 2010, 105, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. The Influence of Adolescents’ Daily Stress and Self-esteem on Smart Phone Addiction. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 13, 1753–1768. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, P.; Zhao, S.; Li, D.; Huang, M.; Liu, G. The Effect of Perceived Stress on College Students’ Mobile Phone Addiction:A Serial Mediation Effect of Self-Control and Learning Burnout. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holmberg, J.; Kemani, M.K.; Holmstrom, L.; Ost, L.-G.; Wicksell, R.K. Evaluating the psychometric characteristics of the Work-related Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (WAAQ) in a sample of healthcare professionals. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2019, 14, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change; Guilford press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Galla, B.M.; Tsukayama, E.; Park, D.; Yu, A.; Duckworth, A.L. The mindful adolescent: Developmental changes in nonreactivity to inner experiences and its association with emotional well-being. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-P.; Ko, C.-H.; Kaufman, E.A.; Crowell, S.E.; Hsiao, R.C.; Wang, P.-W.; Lin, J.-J.; Yen, C.-F. Association of stress coping strategies with Internet addiction in college students: The moderating effect of depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 62, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Hao, Z.H.; Lu, G. A survey of the psychological stress of Chinese undergraduates and postgraduates. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 32, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E. Commentary: Mediation Analysis, Causal Process, and Cross-Sectional Data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | 1 | ||||

| 2. Perceived stress | 2.77 | 0.59 | −0.10 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. Experiential avoidance | 3.29 | 1.17 | −0.09 * | 0.67 *** | 1 | ||

| 4. Trait mindfulness | 3.08 | 0.34 | −0.02 | −0.40 *** | −0.31 *** | 1 | |

| 5. Problematic smartphone use | 3.31 | 1.10 | −0.15 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.41 *** | −0.23 *** | 1 |

| Predictors | Model 1 (Problematic Smartphone Use) | Model 2 (Experiential Avoidance) | Model 3 (Problematic Smartphone Use) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | 95% CI | β | SE | t | 95% CI | β | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| Gender | −0.24 | 0.07 | −3.49 *** | [−0.37, −0.10] | −0.06 | 0.06 | −1.03 | [−0.17, 0.05] | −0.22 | 0.67 | −3.35 ** | [−0.35, −0.09] |

| Perceived stress | 0.40 | 0.03 | 12.15 *** | [0.34,0.47] | 0.66 | 0.03 | 24.43 *** | [0.61, 0.72] | 0.25 | 0.04 | 5.71 *** | [0.16, 0.33] |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.23 | 0.04 | 5.34 *** | [0.14, 0.32] | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.21 | |||||||||

| F | 84.74 *** | 304.07 *** | 68.06 *** | |||||||||

| Predictors | Model 1 (Experiential Avoidance) | Model 2 (Problematic Smartphone Use) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | 95% CI | β | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| Gender | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.82 | [−0.16, 0.06] | −0.23 | 0.07 | −3.46 *** | [−0.36, −0.10] |

| Perceived stress | 0.64 | 0.03 | 21.66 *** | [0.58, 0.70] | 0.22 | 0.05 | 4.90 *** | [0.13, 0.31] |

| Trait mindfulness | −0.05 | 0.03 | −1.75 | [−0.11, 0.01] | −0.08 | 0.04 | −2.21 * | [−0.15, −0.01] |

| Trait mindfulness × Perceived stress | −0.06 | 0.02 | −2.76 ** | [−0.10, −0.02] | −0.004 | 0.02 | −0.16 | [−0.05, 0.04] |

| Experiential avoidance | 0.22 | 0.04 | 5.14 *** | [0.14, 0.31] | ||||

| R2 | 0.45 | 0.22 | ||||||

| F | 156.72 *** | 41.98 *** | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Wang, E. Indulging in Smartphones in Times of Stress: A Moderated Mediation Model of Experiential Avoidance and Trait Mindfulness. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120485

Zhang J, Wang E. Indulging in Smartphones in Times of Stress: A Moderated Mediation Model of Experiential Avoidance and Trait Mindfulness. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(12):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120485

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Junjie, and Enna Wang. 2022. "Indulging in Smartphones in Times of Stress: A Moderated Mediation Model of Experiential Avoidance and Trait Mindfulness" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 12: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120485

APA StyleZhang, J., & Wang, E. (2022). Indulging in Smartphones in Times of Stress: A Moderated Mediation Model of Experiential Avoidance and Trait Mindfulness. Behavioral Sciences, 12(12), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120485