1. Introduction

Social media has countless users worldwide and the number is constantly growing. The definition of social media varies [

1]; according to [

2], the definitions of social media presented in the literature and the commonalities among current social media services are: (1) social media services are currently Web 2.0 Internet-based applications; (2) user-generated content is the lifeblood of social media; (3) individuals and groups create user-specific profiles in an app designed and maintained by a social media service; and (4) social media services facilitate the development of social networks online by connecting a profile with those of other individuals or/and groups. Social media functionalities are not only traditionally designed for social networking purposes, but are also widely used for business and work purposes. Hence, many available social media platforms are widely used by organizations for official purposes, including Facebook, WeChat, DingTalk, WhatsApp, Twitter, blogs, YouTube, and photo-sharing sites [

3,

4].

Social media usage at work is regarded as a form of computer-mediated communication adopted by employees for work-related purposes [

4,

5], personal use [

6,

7] or both [

8,

9]. The rising trend of social media use at work has influenced employees to connect with social media, as it integrates with the routine activities of employees’ lives that directly affect their behavior [

10]. Abundant research has discovered that social media use at work could enhance individual job performance, job satisfaction, job productivity, and work engagement as well as strengthen and maintain professional networks within or outside organizations [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Despite the potential benefits of using social media, scholars from several disciplines, including health, psychology, and computer–human behavior, have started to recognize the need to understand the potentially harmful and unintended consequences of social media usage in the workplace. As such, [

15] mentioned that technology usage could have negative effects once it exceeds optimal-level usage. Individuals who continuously use social media tend to suffer from social media overload [

16,

17]. With the growing number of social media users and their activity levels, a large volume of information and communication can be generated that requires users to process it, which indirectly leads to the issues of overload on social media users [

18]. This unpleasant condition is more likely regarded as a major techno-stressor that could negatively impact employees’ job performance [

7,

19]. Hence, there is a phenomenon of social media overload becoming more common, in parallel with social media growth.

Considering social media overload as the antecedent of the adverse outcomes of social media usage, the literature on social media overload has shown the indirect effect on technostress, social media fatigue, and social media exhaustion that subsequently lead to adverse outcomes, such as poor academic performance [

20,

21], discontinuous usage intention [

4,

22], and psychological issues [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Moreover, [

27] found that employees who experienced social media overload suffered from social media exhaustion, leading to low job performance. Undoubtedly, social media overload can act as a specific stressor for technology use that induces strain, leading to adverse behavioral, psychological, and physiological outcomes.

Despite the existing body of knowledge, our understanding of social media overload is still constrained by some persisting gaps in the social media literature. The potential work-related consequences of social media stressors, especially in innovative job performance, remain understudied [

19,

22]. Most prior studies on social media overload concentrated more on general social media users [

28,

29,

30] and students [

31,

32] rather than employees. Furthermore, studies on the different dimensions of overload remain scarce [

30]. In the context of social media, the technostress associated with social media use has been studied primarily through the consequences of behavioral and psychological response [

33,

34,

35,

36] and little attention, to date, has been paid to the potential work-related outcomes, such as innovative job performance. Thus, this study provides a detailed investigation into how the association between social media use at work and social media overload can induce psychological strain that interferes with employees’ innovative job performance. The study focuses specifically on the use of WhatsApp in the Malaysian context.

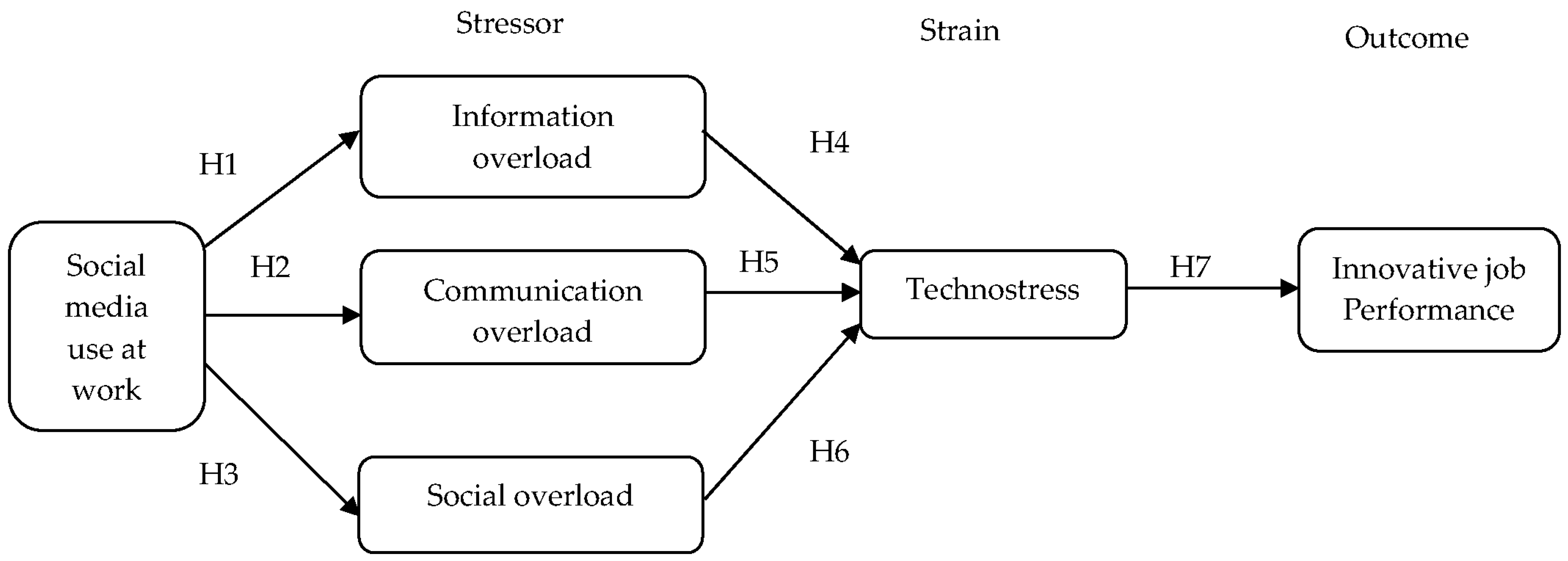

The growing number of social media users, especially WhatsApp users, among employees has led to the phenomenon of social media overload. A large volume of information, communication, and social interaction may be generated from personal or work purposes, or both, which requires employees to process this information indirectly and excessively. Facing the same problems as other emerging technologies, social media use in the workplace has become contentious [

9]. In addition, previous studies have shown inconsistent or mixed findings regarding whether social media use at work can increase or hinder employees’ job performance [

1,

3,

27,

37]. This study argues that this is a critical gap, because personal social media and smartphone use have significantly increased during working hours [

38]. In consequence, employees cannot cope with this stressful situation, which may induce employee strain that turns into technostress. Hence, this study explores this undesirable situation by adapting the stressor–strain–outcome (SSO) model. Through the SSO model, the relationships between the different dimensions of social media overload are tested for their influence on technostress and, subsequently, the impact of social media overload on employees’ innovative job performance.

4. Results

4.1. Data Preparation

Data screening and cleaning will result in data exclusion. The reasons for data to be excluded are because of the straight lining, missing values, and redundant responses from the same respondents. The first step in data cleaning is checking the blank response among the collected responses. To treat the blank responses, this study used the formula COUNTBLANK (item1 to item28) in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, DC, USA) before transferring the data into SPSS. The results found no blank response in the data, confirming the respondents answered all questions. Thus, no missing value data issues were reported in this study since the questions in the Google form were arranged in mandatory responses. The data were automatically stored in the Google form. Hence, treatment for missing values is not implemented in this study.

The authors of [

77] explained that straight lining occurs when respondents provide identical answers to the questions using the same response scale. This study treated the straight-lining assessment by applying the formula standard deviation function in Microsoft Excel 2016. Using the formula of STDEV (item1 to item28), 2 of 208 responses were detected with straight lining with zero values. Therefore, these two responses were excluded from further analysis, leaving 206 remaining responses to be analyzed.

4.2. Demographic Information

Table 3 presents the demographic information of the 206 respondents. With reference to gender, 46.1 percent (95) were male, whereas 53.9 percent (111) were female. In terms of education, the majority of respondents (57.8 percent) are Bachelor’s degree holders and Master’s degree holders (23.3 percent). Furthermore, 28.2 percent of respondents have worked for more than 11–15 years and 6–10 years (19.9 percent). The social media platforms frequently used are WhatsApp (88.3 percent) and Facebook (5.8 percent). As expected, Malaysian employees mostly use WhatsApp as a medium to communicate and interact for work-related purposes due to the compliance, internalization, and identification that influenced the employees to use WhatsApp in their routine work. In addition, The Digital News Report (2017) found that Malaysians are the world’s largest users of WhatsApp at 51%. This result suggests that the predominantly utilized social media platform by Malaysian employees in the workplace is WhatsApp.

4.3. Common Method Bias

A statistical remedy was employed in this study to manage common method bias, which is common in behavioral research [

78,

79]. As such, [

80] suggested that in PLS-SEM, a full collinearity test can be used to assess common method bias and a variance inflation value (VIF) below 3.3 indicates the dataset does not suffer common method bias. There is no significant issue in the dataset, as the VIF values of all constructs are lower than 3.3, as shown in

Table 4.

4.4. Measurement Model

The measurement model is the first stage of using PLS-SEM that specifies the relations between the latent variable (construct) and its indicator (manifest variable). The purpose of measurement model analysis is to ensure all the required relationships between the latent variables and the indicator are met by the model assessment [

75]. For construct reliability and validity, the convergent validity is evaluated by assessing the factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability are for the internal consistency reliability [

74,

81].

Table 5 shows that all the factor loadings exceed the minimum of required value 0.6 for an exploratory study [

82]. Meanwhile, the Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability for all constructs were higher than the required value of 0.7 [

82].

Table 5 presents the measurement model’s construct validity and reliability.

Discriminant validity is essential to ensure that each variable is distinct and not related to each other [

74]. This study applied the Heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlation, which has better performance in measuring the discriminant validity in variance-based SEM compared to the cross-loadings and Fornell Larcker criterion [

83]. The authors of [

84] stated that a cut-off value of HTMT for conceptually dissimilar constructs is less than 0.85, while conceptually similar constructs are less than 0.9, establishing the discriminant validity that reliably distinguishes between those pairs of latent variables, depending on the study context.

Table 6 shows that all the correlation values are below 0.85, suggesting that the variables in this study possess satisfactory discriminant validity.

4.5. Structural Model

This study implemented Mardia’s multivariate kurtosis to measure the normality of data. As [

85] suggested, this study uses the online tool to calculate univariate/multivariate skewness and kurtosis at

http://webpower.psychstat.org/models/kurtosis/ (accessed on 2 August 2022). The results indicate that data were not multivariate normal, as shown by the skewness (

β = 8.351,

p < 0.01) and kurtosis (

β = 62.962,

p < 0.01). This calls for using a nonparametric analysis tool, SmartPLS 3.2.8, to perform bootstrapping.

Following the suggestion of [

70], a 5000 bootstrapping re-sampling technique was performed to assess the structural model based on the path coefficient and statistical significance [

86]. To test the model with different research hypotheses, the path coefficient of exogenous to endogenous variables by the

β-value,

t-values, and squared multiple correlation (R

2) values of explained variance on the endogenous variable were evaluated.

Table 7 shows the result of R

2, f

2, and Q

2; meanwhile,

Table 8 displays the structural analysis results and decision on hypotheses, while

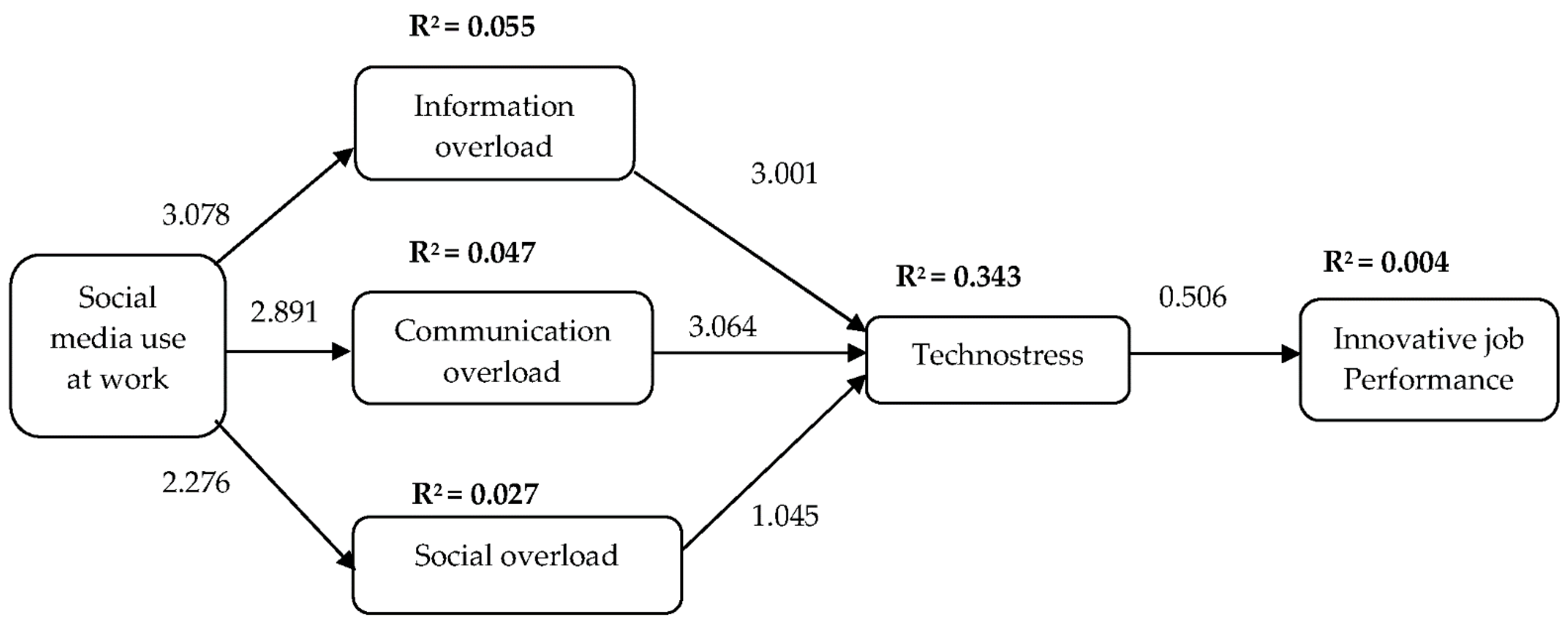

Figure 2 illustrates the structural path.

The result shows that five of the seven proposed hypotheses were supported. As hypothesized, H1, H2, and H3 were supported as social media use at work has a positive influence on information overload (β = 0.234, t = 3.078), communication overload (β = 0.216, t = 2.891), and social overload (β = 0.164, t = 2.276). The R2 of the three variables are 0.055 (Q2 = 0.031), 0.047 (Q2 = 0.031), and 0.027 (Q2 = 0.017), denoting that social media use at work explained 5.5%, 4.7%, and 2.7% of the variance, respectively. Next, H4 and H5 were accepted, which posited that information overload (β = 0.342, t = 3.001) and communication overload (β = 0.343, t = 3.064) showed a significant positive effect on employees’ technostress; meanwhile, social overload on employees’ technostress was not significant (β = −0.089, t = 1.045), thus, rejecting H6. The R2 was 0.343 (Q2 = 0.270), indicating that the three overloads explained 34.3% of the variance on technostress. Lastly, H7 (β = 0.065, t = 0.506) demonstrated that technostress was found to be insignificant towards innovative job performance among employees, with an R2 of 0.004 (Q2 = 0.000), which indicates that technostress explained 0.4% of the variance in innovative performance.

5. Discussion

The study utilized the SSO model to examine how social media use at work predicts social media stressors (information overload, communication overload, and social overload), strain (technostress), and, subsequently, relationship on their innovative job performance. First, the study presented the new outcomes since WhatsApp is a predominant social media platform that predicts social media overloads in the Malaysian workplace. The finding discovered its influence on information overload, communication, and social overload. Based on the findings, H1 (

t = 3.078), H2

(t = 2.891), and H3 (

t = 2.276) showed a

t-value of more than 1.65 and these hypotheses were supported as WhatsApp use at work positively influences information overload, communication overload, and social overload. Even though the findings revealed that the impact of WhatsApp usage is very mild on the three stressors, nevertheless, it significantly stimulates social-media-related overload statistically, hence, contributing to users’ technostress. Consistent with prior studies [

16,

19], pervasive social media access led to technology overload. Due to the integration of social media into work life, employees experience challenges in balancing their professional and private life because work responsibilities may be accessible anywhere and at any time [

87]. With the wide range of social features in social media, a large volume of information, communication, and social interaction may be generated for personal and professional reasons, necessitating employees to process and attend to, indirectly leads to social media overload.

Additionally, H4 (

t = 3.001) and H5 (

t = 2.891) were accepted as a t-value of more than 1.65, positing that information overload and communication overload significantly positively affected employees’ technostress. The findings of this study show that information overload and communication overload contributed to the pervasive phenomenon of technostress among Malaysian employees. As anticipated, these findings are in line with previous studies and highlight the adverse consequence of information overload and communication overload on individuals’ psychological well-being [

18,

30,

54]. Employees who experience information and communication overload are unable to keep up with the high volume of information and communication generated by WhatsApp, as it exceeds their cognitive abilities to process it. This undesirable condition would influence employees’ execution and decision-making capability, resulting in technostress [

88].

Meanwhile, social overload on employees’ technostress was not significant as

t = 1.045,

t-value < 1.65, thus, rejecting H6. This study found that social overload did not contribute to employees’ technostress. Therefore, this finding is inconsistent with past studies [

30,

35,

67]. Social overload mainly focuses on private activities that can be ignored temporarily during work hours and processed later in the desired sequence, contrary to information overload and communication overload, which must be handled immediately at work due to the association with work tasks [

19]. In addition, H7 (

t = 0.506) was rejected, indicating a

t-value < 1.65, demonstrating that technostress was found insignificant towards innovative job performance among Malaysian employees. This result suggests that employees showed effective coping strategies for minimizing, tolerating, and coping with technostress related to exceptional work or social demands from WhatsApp at the workplace. With good coping abilities, this strain and technostress had no effect on employees’ innovative job performance. Hence, employees can show their creative and critical thinking by producing, adopting, promoting, and implementing novel ideas.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

By employing the SSO model, this study contributes to the theoretical understanding of the role of social media use among employees in government departments. The present study provides an essential extension of current research in the form of a detailed theoretical understanding of the psychological mechanism underlying employees’ work behavior, specifically in innovative job performance. In addition, this study examines the process of how WhatsApp use at work plays a significant role in employee’s innovative job performance from the perspective of SSO. The outcome provides a meaningful theoretical contribution to the literature on work-related stress and the effects of WhatsApp use on employee outcomes at the workplace.

It is possible that employees who use WhatsApp at work may be oblivious to the potential fallout from their social media usage. They view WhatsApp as an integral part of their daily life. Considering the fact that Malaysia constitutes the highest number of internet users in the Southeast Asian region, employees should have a greater insight and understanding of WhatsApp usage and its dual consequences (positive or negative) at the workplace. Employees may implement measures to regulate their habits on WhatsApp use in order to avoid adverse consequences on their work behavior, particularly innovative job performance. In addition, the findings of this study offer management with guidance to adopt an emerging and popular technology, social media, especially WhatsApp, as a medium to foster innovativeness among employees. Such a measure can effectively provide practical insights for management to create new strategies in mitigating issues of personal social media usage at work. In addition, management is able to reinforce existing guidelines or policies surrounding the usage of WhatsApp at work to promote better routine and innovative performance, thus, benefiting organizations and ensuring psychological and mental health for a work–life balance among employees.

6.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Work

Although this study offers valuable insights, certain limitations should also be acknowledged and addressed for future studies. First, given the pervasiveness of social media overload and its effects on employees’ innovative job performance, our findings imply that future research should pay closer attention to social media overload, its antecedents, and its outcomes in other types of organizational settings (i.e., private, large corporate organization) or specific industries, such as manufacturing, services, and education. Different contexts would provide a detailed and different understanding of adapting to social media usage, which might influence employees’ innovative job performance.

Second, this study highlighted solely on the negative consequences of social media use at work. Future studies should explore both the harmful and beneficial effects of social media use at work by integrating two theories/models (e.g., the SSO model and social capital theory). We believe that researchers in other disciplines can improve the understanding of social media use at work and employees’ outcomes by combining theories from different, multiple perspectives.

Third, this study performed a cross-sectional design, in which data were collected from a single source response. Although the statistical result revealed no evidence of common method bias, it is possible that respondents might be unable to provide accurate information when responding to sensitive questions about their physical and mental health. Future scholars should consider applying a mixed-method design by adding interview sessions or observation to accurately measure employees’ technostress and innovative job performance.

Next, this study was carried out with users who predominantly utilized WhatsApp as their medium for work-related purposes. Hence, the findings might be restrained and impractical to other social media platforms. Furthermore, the generalizability of the current study is somewhat limited because the interaction on WhatsApp is often limited to close contacts or specific social groups and not intended for the public at large [

20]. Therefore, scholars should consider replicating the study method in different social media platforms at work, either for combined or exclusive usage. Then, the different platforms would produce an exact effect of social media usage at work on social media overloads.

This study also has geographical limitations that prevent generalization to other countries. Since this study was performed in Malaysia, the findings only apply to users with comparable demographic information and similar work culture. Thus, scholars should use this model as a foundation for future studies on similar respondents from different countries to strengthen the results’ validity and reliability.

Lastly, future scholars should consider conducting a cross-sectional or longitudinal study by reversing causation in the relationship between social media and stress, especially in the workplace setting. This study focused on the roles of social media toward technostress issues by discussing the consequences of social media use at work. To gain a clear picture of the social-media–technostress link, the direction of social media causing psychological well-being problems might instead be reversed. As [

89] mentioned, future research needs to move toward a deeper analysis of the reverse possibility underlying social media use.

Overall, this study presents the exact mechanism of crucial roles of WhatsApp use at work and its influence on employees’ innovative performance. The discussion of the findings shows that most of the hypotheses are congruent with prior studies. This study suggests that WhatsApp use at work mildly predicts social media overloads, including information overload, communication overload, and social overload. Furthermore, the findings found that these overloads, except social overload, induced employees’ technostress. However, this strain indicates that technostress has not significantly affected employees’ innovative performance. The findings of this study provide an essential extension of prior knowledge on the conceptual relationships for social media overloads that were empirically validated in terms of technostress and employee outcomes. Moreover, the outcomes of this study will be of immense benefit to both employees and employers in enhancing the association between social media use at work and increasing employees’ innovative job performance.