Toxic Leadership and Project Success: Underpinning the Role of Cronyism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

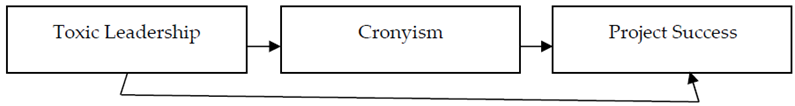

1.2. Toxic Leadership and Project Success

1.3. Cronyism as a Mediator

2. Methodology

2.1. Sampling and Data Collection

2.2. Survey Instrument

2.2.1. Cronyism

2.2.2. Toxic Leadership

2.2.3. Project Success

3. Data Analysis and Results

3.1. Measurement Model/CFA Analysis

3.2. Structural Model Analysis

4. Discussion

Managerial and Practical Implications

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilir, C.; Yafez, E. Project success/failure rates in Turkey. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2021, 9, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahie, A.M.; Osman, A.A.; Omar, A.A. The role of project management in achieving project success: Empirical study from local NGOs in Mogadishu-Somalia. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2017, 7, 14844. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, D.; Fatima, T.; Jahanzeb, S. Cronies, procrastinators, and leaders: A conservation of resources perspective on employees’ responses to organizational cronyism. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2022, 31, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, T.; Ljung, L. Projektledningsmetodik; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2004; pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.R.; Huang, C.F.; Wu, K.S. The association among project manager’s leadership style, teamwork and project success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2011, 29, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Florez-Perez, L.; Anjam, M.; Khwaja, M.G.; Ul-Huda, N. At the end of the world, turn left: Examining toxic leadership, team silence and success in mega construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Wang, L.; Yu, M.; Müller, R.; Sun, X. Transformational leadership and project team members’ silence: The mediating role of feeling trusted. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 845–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Malik, M.I.; Malik, M.K. Toxic Leadership and Safety Performance: Does Organizational Commitment act as Stress Moderator? Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1960246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, A.; Arif, M. Employee silence as mediator in the relationship between toxic leadership behavior and organizational learning. Abasyn J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 10, 294–310. [Google Scholar]

- Indradevi, R. Toxic leadership over the years—A review. Purushartha-J. Manag. Ethics Spiritual. 2016, 9, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Whicker, M.L. Toxic Leaders: When Organizations Go Bad; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 1996; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vreja, L.O.; Balan, S.; Bosca, L.C. Toxic leadership. An evolutionary perspective. In Proceedings of the International Management Conference, Bucharest, Romania, 3–4 November 2016; Volume 10, pp. 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Shahzad, F.; Hussain, I.; Yongjian, P.; Khan, M.M.; Iqbal, Z. The Outcomes of Organizational Cronyism: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 805262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman-Blumen, J. Toxic leadership: A conceptual framework. In Handbook of Top Management Teams; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kusy, M.; Holloway, E. Toxic Workplace: Managing Toxic Personalities and Their Systems of Power; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.E. Toxic Leadership in Educational Organizations. Educ. Lead. Rev. 2014, 15, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, R.M. The Dysfunction Junction: The Impact of Toxic Leadership on Follower Effectiveness. Ph.D. Thesis, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 2017; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Veldsman, T.H.; Johnson, A.J. Leadership: Perspectives from the Front Line; KR Publishing: Waukesha, WI, USA, 2016; pp. 12–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman-Blumen, J. The Allure of Toxic Leaders: Why We Follow Destructive Bosses and Corrupt Politicians—And How We Can Survive Them; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tekiner, M.A.; Aydın, R. Analysis of Relationship Between Favoritism and Officer Motivation: Evidence from Turkish Police Force. Inquiry 2016, 1, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, K.L.; Bligh, M.C. The aftermath of organizational corruption: Employee attributions and emotional reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 823–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zha, H.; Song, L. Learning social infectivity in sparse low-rank networks using multi-dimensional hawkes processes. Artif. Intell. Stat. 2013, 31, 641–649. [Google Scholar]

- Khatri, N.; Tsang, E.W.; Begley, T.M. Cronyism: A cross-cultural analysis. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khouri, A.M.; Bal, J. Electronic government in the GCC countries. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2007, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, P.; Mota, C. Perceptions of success and failure factors in information technology projects: A study from Brazilian companies. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 119, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, D.C. The Relationship between Information Technology Project Manager Personality Type and Project Success. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2008; pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ekeh, P.P. Social Exchange Theory: The Two Traditions; Heinemann: London, UK, 1974; pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Vischer, J.C. The effects of the physical environment on job performance: Towards a theoretical model of workspace stress. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2007, 23, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfong, J.D. Organizational Culture and Information Technology (IT) Project Success and Failure Factors: A Mixed-Methods Study Using the Competing Values Framework and Schein’s Three Levels Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Saybrook University, Pasadena, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, K.L. Leader toxicity: An empirical investigation of toxic behavior and rhetoric. Leadership 2010, 6, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, N.; Tsang, E.W. Antecedents and consequences of cronyism in organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amunkete, S.; Rothmann, S. Authentic leadership, psychological capital, job satisfaction and intention to leave in state-owned enterprises. J. Psychol. Afr. 2015, 25, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipton, H.; Sanders, K.; Atkinson, C.; Frenkel, S. Sense-giving in health care: The relationship between the HR roles of line managers and employee commitment. Hum. Res. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, A.; Hogan, R.; Kaiser, R.B. The toxic triangle: Destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.E. Toxic leadership. Millenn. Rev. 2004, 84, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N. Leader-member exchange (LMX) theory: The relational approach to leadership. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 407–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, K.H. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide)—Fifth Edition. Proj. Manag. J. 2013, 44, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, J.T.; Lereim, J. Management of project contingency and allowance. Cost Eng. 2005, 47, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, R.; Jugdev, K. Critical success factors in projects: Pinto, Slevin, and Prescott-the elucidation of project success. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2012, 5, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrnhur, A.J.; Levy, O.; Dvir, D. Mapping the dimensions of project success. Proj. Manag. J. 1997, 28, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Thite, M. Leadership styles in information technology projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2000, 18, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H.; Keshavarzsaleh, A. A theoretical review on IT project success/failure factors and evaluating the associated risks. In Mathematical and Computational Methods in Electrical Engineering; WSEAS Press: Attica, Greece, 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P. Transforming Economics: Perspectives on the Critical Realist Project; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2004; pp. 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Roy-Girard, D. Toxins in the workplace: Affect on organizations and employees. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadadian, Z.; Zarei, J. Relationship between toxic leadership and job stress of knowledge workers. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2016, 11, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Q.L. A Comprehensive Review of Toxic Leadership; Air War College, Air University Maxwell AFB: Montgomery, AL, USA, 2016; pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bagi, S. When leaders burn out: The causes, costs and prevention of burnout among leaders’. Interdiscip. Perspect. Int. Leadersh. 2013, 20, 261–289. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, J.P.; Pae, H.A.; Bausmith, S.C.; O’Connor, D.M. Project CREATE: State-wide partnership for producing highly qualified special education teachers. Publ. Law 2001, 107, 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.A. Development and Validation of the Toxic Leadership Scale. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Veldsman, T.H. How toxic leaders destroy people as well as organisations. The Conversation, 14 January 2016; 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Priest, N.; Williams, D.R. Racial discrimination and racial disparities in health. In The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health; Major, B., Dovidio, J.F., Link, B.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Maheshwari, G.C. Toxic leadership: Tracing the destructive trail. Int. J. Manag. 2014, 5, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K.J.; Kacmar, K.M.; Zivnuska, S.; Shaw, J.D. The impact of political skill on impression management effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboyassin, N.A.; Abood, N. The effect of ineffective leadership on individual and organizational performance in Jordanian institutions. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2013, 23, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.F.; Bonial, R.; Vanhove, A.; Kedharnath, U. Leading across cultures in the human age: An empirical investigation of intercultural competency among global leaders. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, D.W. The Effect of Toxic Leadership. Strategy Research Project, United States Army War College. 2012. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA560645.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Erdem, B.; Karataş, A. The effects of cronyism on job satisfaction and intention to quit the job in hotel enterprises: The case of three, four and five star hotels in muğla, turkey. Manas Sos. Araştırmalar Derg. 2015, 4, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Arasli, H.; Tumer, M. Nepotism, Favoritism and Cronyism: A study of their effects on job stress and job satisfaction in the banking industry of north Cyprus. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2008, 36, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.C.; Kleiner, B.H. Nepotism. Work Study 1994, 43, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, H.F.; Maghrabi, A.S.; Raggad, B.G. Assessing the perceptions of human resource managers toward nepotism. Int. J. Manpow. 1998, 19, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.R.; McAbee, S.T.; Hebl, M.R.; Rodgers, J.R. The impact of interpersonal discrimination and stress on health and performance for early career STEM academicians. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, S.; Bashir, S.; Khan, A.K. Examining organizational cronyism as an antecedent of workplace deviance in public sector organizations. Public Pers. Manag. 2017, 46, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büte, M. The effects of nepotism and favoritism on employee behaviors and human resources practices: A research on Turkish public banks. TODAĐE’s Rev. Public Adm. 2011, 5, 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, N.; Qureshi, R. Khandan and Talluqat as social capital for women’s career advancement in Pakistan: A study of NGO sector in Islamabad. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Gender Research, Porto, Portugal, 12–13 April 2018; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2018; pp. 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cingoz, A.; Akilli, H.S. A study on examining the relationship among cronyism, self-reported job performance, and organizational trust. In Proceedings of the 2015 WEI International Academic Conference, Vienna, Austria, 12–15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shabbir, B.; Siddique, H. Impact of Nepotism, Cronyism, and Favoritism on Organizational Performance with a Strong Moderator of Religiosity. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2017, 8, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Asgharian, R.; Anvari, R.; Ahmad, U.N.U.B.; Tehrani, A.M. The mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between workplace friendships and turnover intention in Iran hotel industry. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philibin, C.A.N.; Griffiths, C.; Byrne, G.; Horan, P.; Brady, A.M.; Begley, C. The role of the public health nurse in a changing society. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, T.K.P.; Bradley, R.B. Ethical cronyism: An insider approach for building guanxi and leveraging business performance in China. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2020, 26, 124–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.Y.; Chow, C.W.; Loi, R. The interactive effect of LMX and LMX differentiation on followers’ job burnout: Evidence from tourism industry in Hong Kong. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2018, 29, 1972–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayajenh, A.F.; Maghrabi, A.S.; Al-Dabbagh, T.H. Research note: Assessing the effect of nepotism on human resource managers. Int. J. Manpow. 1994, 15, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, M. Organizational cronyism: A scale development and validation from the perspective of teachers. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R. IT project management: Infamous failures, classic mistakes, and best practices. MIS Q. Exec. 2007, 6, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Qual. Res. 1981, 18, 199–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan, I. Impact of Abusive Leadership on Project Success with Mediating Role of Workplace Deviance and Moderating Role of Agreeableness. Ph.D. Thesis, Capital University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2020; pp. 71–99. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, M.; Ali, R. Transformational versus transactional leadership styles and project success: A meta-analytic review. Eur. Manag. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M.A. Leadership and organizational distress: Review of literature. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J. Influence of nurse managers’ toxic leadership behaviours on nurse-reported adverse events and quality of care. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtulmuş, B.E. Toxic leadership and workplace bullying: The role of followers and possible coping strategies. In The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Well-Being; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pimenta, F.X.E. Toxicity at Work Place: Coping Strategies to Reduce Toxins at Work Place. ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, I.M.; Bilal, A.R.; Fatima, T.; Mohammed, Z.J. Does organizational cronyism undermine social capital? Testing the mediating role of workplace ostracism and the moderating role of workplace incivility. Career Dev. Int. 2021, 26, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergen, A.; Ozbilgin, M.F. Understanding the followers of toxic leaders: Toxicillusiono and personal uncertainty. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N. Sifarish, sycophants, power and collectivism: Administrative culture in Pakistan. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2004, 70, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 165 | 68.8 |

| Female | 75 | 31.2 | |

| Age (years) | 26–35 | 88 | 36.7 |

| 36–45 | 101 | 42.1 | |

| 46–55 | 51 | 21.2 | |

| Education | Below graduation | 38 | 15.8 |

| Graduation | 44 | 18.3 | |

| Masters | 158 | 65.9 | |

| Experience (years) | Less than 1 | 71 | 29.6 |

| 1–5 | 93 | 38.8 | |

| 6–10 | 33 | 13.7 | |

| 11–15 | 23 | 9.6 | |

| 15 and more | 20 | 8.3 |

| Construct | Loading | C.R. | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxic leadership | 0.975 | 0.770 | |

| TL1 | 0.764 | ||

| TL2 | 0.792 | ||

| TL3 | 0.862 | ||

| TL4 | 0.799 | ||

| TL5 | 0.775 | ||

| TL6 | 0.883 | ||

| TL7 | 0.766 | ||

| TL8 | 0.789 | ||

| TL9 | 0.766 | ||

| TL10 | 0.876 | ||

| TL11 | 0.832 | ||

| TL12 | 0.763 | ||

| TL13 | 0.761 | ||

| TL14 | 0.855 | ||

| TL15 | 0.783 | ||

| Cronyism | 0.966 | 0.727 | |

| CR1 | 0.870 | ||

| CR2 | 0.701 | ||

| CR3 | 0.776 | ||

| CR4 | 0.889 | ||

| CR5 | 0.752 | ||

| CR6 | 0.862 | ||

| CR7 | 0.779 | ||

| CR8 | 0.754 | ||

| CR9 | 0.897 | ||

| Project success | 0.969 | 0.744 | |

| PS1 | 0.875 | ||

| PS2 | 0.858 | ||

| PS3 | 0.868 | ||

| PS4 | 0.863 | ||

| PS5 | 0.873 | ||

| PS6 | 0.874 | ||

| PS7 | 0.870 | ||

| PS8 | 0.812 | ||

| PS9 | 0.855 | ||

| PS10 | 0.881 | ||

| PS11 | 0.866 |

| Constructs | TL | CR | PS |

|---|---|---|---|

| TL | 0.877 | ||

| CR | 0.702 | 0.852 | |

| PS | 0.492 | 0.521 | 0.862 |

| Relationship | Coefficient | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| TL--->PS (direct) | −0.542 | 0.000 |

| TL--->PS | 0.634 | 0.000 |

| TL--->CR--->PS | 0.327 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saleem, F.; Malik, M.I.; Hyder, S.; Perveen, A. Toxic Leadership and Project Success: Underpinning the Role of Cronyism. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110427

Saleem F, Malik MI, Hyder S, Perveen A. Toxic Leadership and Project Success: Underpinning the Role of Cronyism. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(11):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110427

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaleem, Farida, Muhammad Imran Malik, Shabir Hyder, and Ambrin Perveen. 2022. "Toxic Leadership and Project Success: Underpinning the Role of Cronyism" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 11: 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110427

APA StyleSaleem, F., Malik, M. I., Hyder, S., & Perveen, A. (2022). Toxic Leadership and Project Success: Underpinning the Role of Cronyism. Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110427