Impact of Staff Localization on Turnover: The Role of a Foreign Subsidiary CEO

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review of Subsidiary Staffing

2.2. Literature Reviews of Psychological Contract and Turnover

2.3. Hypothesis Deveopment

2.3.1. Staff Localization and Turnover

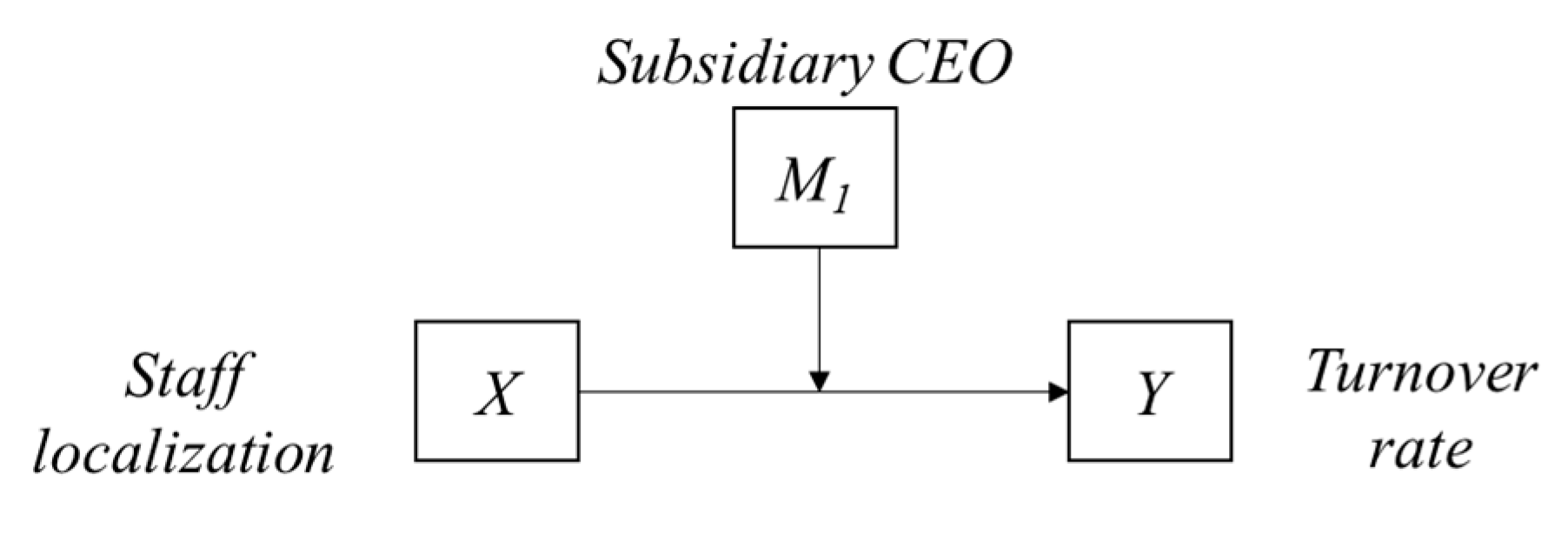

2.3.2. Moderating Effect of a Foreign Subsidiary CEO’s Nationality

3. Method

3.1. Case Setting and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Instrument

3.3. Analytic Procedure

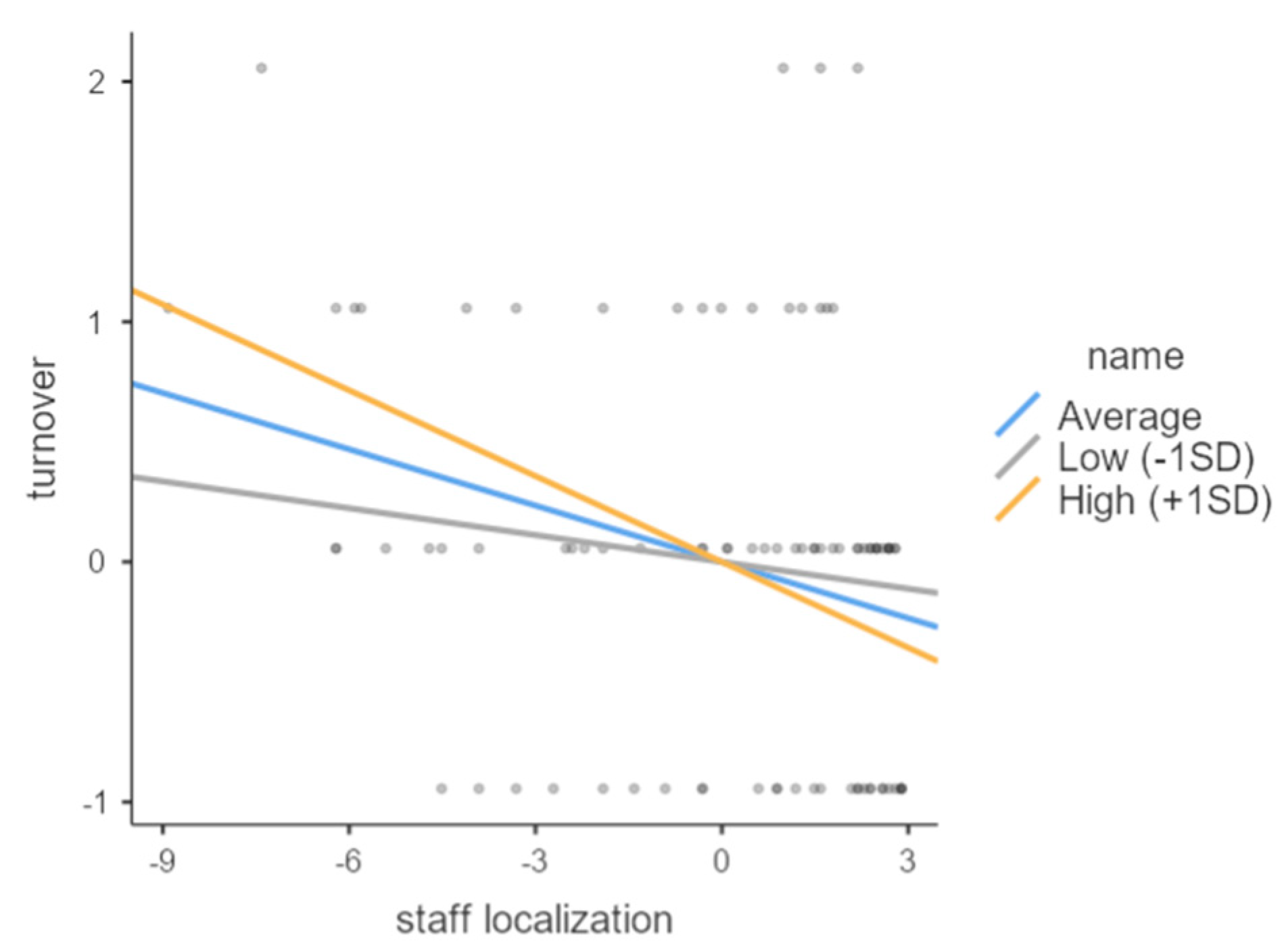

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Results

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, Y.-T.; Gyamfi, N.Y.A. Cultural Contingencies of Resources: (Re)Conceptualizing Domestic Employees in the Context of Globalization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2022. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Lamond, D. A critical review of human resource management studies (1978–2007) in the People’s Republic of China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 2194–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A. The link between organizational elements, perceived external prestige and performance. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2004, 6, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.B.; Choi, S.J.; Zhang, L. Determinants of Staff Localization in Headquarters-Subsidiary-Subsidiary Relationships. Sustainability 2021, 14, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2003 FDI Policies for Development: National and International Perspectives; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, M.G.; Buckley, M.R. Managing Inpatriates: Building a Global Core Competency. J. World Bus. 1997, 32, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayol-Song, L. The Reasons behind Management Localization: A Case Study of China. J. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2001, 17, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.; Pak, Y.S. Staff localization strategy and host country nationals’ turnover intention. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 1916–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Shuanglin, L.; Vai, I.L. Foreign direct investment and economic performance in transition economies: Evidence from China. Post-Communist Econ. 2004, 16, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitotsuyanagi-Hansel, A.; Froese, F.J.; Pak, Y.S. Lessening the divide in foreign subsidiaries: The influence of localization on the organizational commitment and turnover intention of host country nationals. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, A.K.; Froese, F.J.; Achteresch, A.; Behrens, S. Expatriates’ influence on the affective commitment of host country nationals in China: The moderating effects of individual values and status characteristics. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2017, 11, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A.; Shaffer, M.A.; Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P. Going places: Roads more and less travelled in research on expatriate experiences. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 23, 199–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencturk, E.F.; Aulakh, P.S. The use of process and output controls in foreign markets. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1995, 26, 755–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.; Morrison, A. Implementing Global Strategy: Characteristics of Global Subsidiary Mandates. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1992, 23, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Liu, X.; Gao, L.; Xia, E. Expatriates, subsidiary autonomy and the overseas subsidiary performance of MNEs from an emerging economy. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 29, 1799–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.J. Entrepreneurship in multinational corporations: The characteristics of subsidiary initiatives. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailey, J. Localisation and Expatriation: The Continuing Role of Expatriates in Developing Countries; School of Management, Working Paper; EISAM Workshop: Cranfield, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Peltokorpi, V.; Sekiguchi, T.; Yamao, S. Expatriate justice and host country nationals’ work outcomes: Does host country nationals’ language proficiency matter? J. Int. Manag. 2021, 27, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakiants, I.; Dorner, G. Using social media and online collaboration technology in expatriate management: Benefits, challenges, and recommendations. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 63, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, J. A business case for localization. Int. Hum. Resour. J. 2003, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Selmer, J. Staff localization and organizational characteristics: Western business operations in China. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2003, 10, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Oliveria RTd Barker, M.; Moeller, M.; Nguyen, T. Expatriate family adjustment: How organisational support on international assignments matters. J. Int. Manag. 2022, 28, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield. 2014 Global Mobility Trends Survey; Brookfield Global Relocation Services: Burr Ridge, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, L. The use of expatriate managers in international joint ventures. J. Comp. Int. Manag. 2004, 7, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Swati, L.K. China’s Impeding Talent Shortage. China Business; Asia Times Online Ltd.: Hong Kong, China, 2006; Available online: http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China_Business/HE06Cbos.html (accessed on 6 July 2006).

- Ando, N. The Effect of Localization on Subsidiary Performance in Japanese Multinational Corporations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1995–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Mahoney, J.T. Why a Multinational Firm Chooses Expatriates: Integrating Resource-Based, Agency and Transacton Cost Perspectives. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmier, S.; Broughers, L.E.; Beamish, P.W. Expatriate or Local? Predicting Japanese, Subsidiary Expatriates Staffing Strategies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1607–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.S.; Song, J.J.; Wong, C.S.; Chen, D. The Antecedents and Consequences of Successful Localization. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.; Sofka, W. Liability of Foreignness as a Barrier to Knowledge Spillovers: Lost in Translation? J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Butler, J.; Choi, A. Successful localization programs in China: An important element in strategy implementation. J. World Bus. 2004, 39, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmer, J. Expatriates’ hesitation and the localization of Western business operations in China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. 2004, 15, 1094–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmer, J. Psychological barriers to adjustment of Western business expatriates in China: Newcomers vs. long stayers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. 2004, 15, 794–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailey, J. The expatriate myth: Cross-cultural perceptions of expatriate managers. Int. Exec. 1996, 38, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamani, M. Changed Identities: The Challenge of the New Generation in Saudi Arabia; Royal Institute of International Affairs: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, P.; Brewster, C.; Chung, C. Globalizing Human Resource Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman, I.; Lasserre, P.; Ching, P.S. Developing Managerial Resources in China; Financial Times: Hong Kong, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moideenkutty, U.; Murthy, Y.; Al-Lamky, A. Localization HRM practices and financial performance: Evidence from the Sultanate of Oman. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2016, 26, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banai, M.; Harry, W. Boundaryless global careers: The international itinerants. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2004, 34, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scullion, H.; Brewster, C. The management of expatriates: Messages from Europe? J. World Bus. 2001, 36, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.S. Globalizing People through International Assignments; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harzing, A.W. The persistent myth of high expatriate failure rates. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1995, 6, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, W.; Collings, D.G. Localisation: Societies, Organisations and Employees; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen, H.B.; Black, J.S. Antecedents to commitment to a parent company and a foreign operation. Acad. Manag. Ann. 1992, 35, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J. Localizing management in foreign-invested enterprises in China: Practical, cultural, and strategic perspectives. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 883–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Justice in social exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. Complex Organizations: A Sociological Reader, Holt; Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, H. Reciprocation: The relationship between man and organization. Adm. Sci. Q. 1965, 9, 370–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wayne, S.J.; Glibkowski, B.C.; Bravo, J. The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 647–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C. Trust and the psychological contract. Empl. Relat. 2007, 29, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, S. The effect of International Staffing practices on subsidiary staff retention in multinational corporations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G. Social Behavior; Harcourt Brace Jonvanovich: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Aselage, J.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: A theoretical integration. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Psychology; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M. Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1989, 2, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. The psychology of the employment relationship: An analysis based on the psychological contract. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 53, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnley, W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Re-examining the effects of psychological contract violations: Unmet expectations and job dissatisfaction as mediators. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sull, D.; Sull, C.; Zweig, B. Toxic Culture Is Driving the Great Resignation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2022. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/toxic-culture-is-driving-the-great-resignation/ (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Robinson, S.L.; Rousseau, D.M. Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Kraatz, M.S.; Rousseau, D.M. Changing obligations and the psychological contract: A longitudinal study. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.S.; Wong, C.-S.; Wang, K.D. An empirical test of the model on managing the localization of human resources in the People’s Republic of China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 15, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.S.; Law, K. Managing localization of human resources in the PRC: A practical model. J. World Bus. 1999, 34, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glebbeek, A.C.; Bax, E.H. Is high employee turnover really harmful? An empirical test using company records. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtom, B.C.; Mitchell, T.R.; Lee, T.W.; Eberly, M.B. Turnover and retention research: A glance at the past, a closer review of the present, and a venture into the future. In Academy of Management Annals; Walsh, J.P., Brief, A.P., Eds.; Routledge: Essex, UK, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 231–274. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley, W.H. Some unanswered questions in turnover and withdrawal research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.; Denisi, A.S. Host country national reactions to expatriate pay policies: A model and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidman, N.; Elisha, D. What generates the violation of psychological contracts at multinational corporations? A contextual exploratory study. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2016, 16, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohria, N.; Ghoshal, S. Differentiated fit and shared values: Alternatives for managing headquarters-subsidiary relations. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, M.; Johanson, J. Managing internationalization in business networks. In Managing Networks in International Business; Forsgren, M., Johanson, J., Eds.; Gordon & Breach: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yamin, M.O.; Andersson, U. Subsidiary importance in the MNC: What role does internal embeddedness play? Int. Bus. Rev. 2011, 20, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickley, M.; Karim, S. Managing institutional distance: Examining how firm-specific advantages impact foreign subsidiary CEO staffing. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, P.M.; Nohria, N. Influences on human resource management practices in multinational corporations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1994, 25, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Deloof, M.; Jorissen, A. Active boards of directors in foreign subsidiaries. Corp. Gov. 2011, 19, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Govindarajan, V. Knowledge flows and the structure of control within multinational corporations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 768–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suazo, M.M.; Martínez, P.G.; Sandoval, R. Creating psychological and legal contracts through human resource practices: A signaling theory perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.J.; Hendry, C. Ordering top pay: Interpreting the signals. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1443–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraimer, M.; Bolino, M.; Mead, B. Themes in expatriate and repatriate research over four decades: What do we know and what do we still need to learn? Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchait, P.; Cho, S.H. The impact of human resource management practices on intention to leave of employees in the service industry in India: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1228–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Chua, C.H.; Caligiuri, P.; Cerdin, J.L.; Taniguchi, M. Predictors of turnover intentions in learning-driven and demand-driven international assignments: The role of repatriation concerns, satisfaction with company support, and perceived career advancement opportunities. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D.; Schneider, M.J.; Popovich, D.L.; Bakamitsos, G.A. Mean centering helps alleviate “micro” but not “macro” multicollinearity. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 1308–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Sparrow, P.; Bozkurt, Ö. South Korean MNEs’ international HRM approach: Hybridization of global standards and local practices. J. World Bus. 2014, 49, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmert, M.; Cross, A.; Cheng, Y.; Kim, J.J.; Kohlbacher, F.; Kotosaka, M. The distinctiveness and diversity of entrpereneurial ecosystems in China, Japan, and South Korea: An exploratory analysis. Asian Bus. Manag. 2019, 18, 211–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, F.J. Doing Business in Korea; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S.; Rivero, J.C. Organizational characteristics as predictors of personnel practices. Pers. Psychol. 1989, 42, 727–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P.; Griffeth, R.W. Employee Turnover; South-Western: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J.P. Alternative pay practices and employee turnover: An organization economics perspective. Group Organ. Manag. 2000, 25, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Morrison, A.; Hulland, J. Structural and competitive determinants of a global integration strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; SAGE: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard, J.; Wan, C.K.; Turrisi, R. The detection and interpretation of interaction effects between continuous variables in multiple regression. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1990, 25, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutaula, S.; Gilliani, A.; Leonidou, L.C.; Palihawadana, D. Exploring frontline employee-customer linkages: A psychological contract perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manamgnet 2022, 33, 1848–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.R.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.W. How Leaders’ Positive Feedback Influences Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Mediating Role of Voice Behavior and Job Autonomy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-H.; Liao, Y.-S. Expatriate CEO assignment: A study of multinational corporations’ subsidiaries in Taiwan. Int. J. Manpow. 2009, 30, 853–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Shen, J. Antecedents and consequences of host-country nationals’ attitudes and behaviors toward expatriates: What we do and do not know. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kang, S.W.; Choi, S.B. Servant Leadership and Creativity: A Study of the Sequential Mediating Roles of Psychological Safety and Employee Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 807070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, M.; Rochford, E. Psychological contract breach and turnover intention: The moderating effects of social status and local ties. Ir. J. Manag. 2017, 36, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, R.L. New perspectives on human resource management in a global context. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.G.; Scullion, H.; Morley, M. Changing patterns of global staffing in the multinational enterprise: Challenges to conventional expatriate assignments and emerging alternatives. J. World Bus. 2007, 42, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-G.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. Leader’s Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility and Team Members’ Psychological Well-Being: Mediating Effects of Value Congruence Climate and Pro-Social Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachani, S. Problems of foreign subsidiaries of SMEs compared with large companies. Int. Bus. Rev. 2005, 14, 145–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, B. Do CEO characteristics explain firm performance in India? J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarova, L.; Jo, S.-J. Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Impact of Environmental Transformational Leadership and GHRM. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. The role of grit in organizational performance during a pandemic. Fron. Psychol. 2022, 13, 929517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Steven, B.; Kim, Y.S. Diversity climate on turnover intentions: A sequential mediating effect of personal diversity value and affective commitment. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-R.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Abusive Supervision and Employee’s Creative Performance: A Serial Mediation Model of Relational Conflict and Employee Silence. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeb, D.; Sakakibara, M.; Mahmood, I. From the Editors: Endogeneity in international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J. Does “familiness” enhance or reduce firms’ willingness to engage in partnership with rivals? Empirical evidence from South Korean savings banks. Asian Bus. Manag. 2021. Advance online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, B.; Lee, J.H. Regression-based mediation analysis: A formula for the bias due to an unobserved precursor variable. J. Korean. Stat. Soc. 2021, 50, 1058–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antecedents | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| -Planning and selection of expatriate (Fryxell et al., 2004 [31]) -Willingness of expatriate to train local managers (Selmer, 2004a [32]) -Identified selection, recruitment and retention of suitable local employees (Selmer, 2004b [33]) -Local government, local managers and a firm’s parent company (Hailey, 1996 [34]) -Fears of growing unemployment and economic and demographic factors (Yamani, 2000 [35]) -Clear preference of restricting jobs for the locals (Sparrow et al., 2016 [36]) | -Cost reduction, local market knowledge, and retention of local managers (Bjorkman et al., 1997 [37]) -Cost reduction, avoidance of expatriation drawbacks, a deepening of local knowledge, and development and retention of local managerial talents (Fayol-song, 2011 [7]) -Cost reduction by 50% (Hauser, 2003 [20]) -Average ratio of market value to book value (Moideenkutty et al., 2016 [38]) -Cost effectiveness (Banai and Harry, 2004 [39]; Scullion and Brewster, 2001 [40]; Black, 1999 [41]; Harzing, 1995 [42]) -High performance compared to expatriates (Harry and Collings [43], 2006; Gregersen and Black, 1992 [44]; Gamble, 2000 [45]) |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Staff localization | 97.1 | 2.93 | - | ||

| 2. Turnover | 2.19 | 0.98 | −0.29 ** | - | |

| 3. CEO nationality | 0.64 | 0.48 | −0.19 * | 0.24 * | - |

| 4. Size | 2.97 | 1.46 | 0.29 * | −0.19 * | −0.05 |

| Variables | Turnover | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Control variable | ||||

| Size | −0.131 | −0.080 | −0.086 | −0.072 |

| Independent variable | ||||

| Staff localization | −0.085 * | −0.075 * | −0.72 * | |

| Moderating variable | ||||

| CEO’s nationality | 0.483 * | 0.510 ** | ||

| Moderating variable | ||||

| Staff localization × CEO’s nationality | −0.132 * | |||

| ΔR2 | 0.058 | 0.051 | 0.030 | |

| R2 | 0.037 | 0.095 | 0.147 | 0.177 |

| F | 3.364 * | 4.536 * | 4.878 ** | 4.519 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J. Impact of Staff Localization on Turnover: The Role of a Foreign Subsidiary CEO. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100402

Lee J. Impact of Staff Localization on Turnover: The Role of a Foreign Subsidiary CEO. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(10):402. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100402

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Joonghak. 2022. "Impact of Staff Localization on Turnover: The Role of a Foreign Subsidiary CEO" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 10: 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100402

APA StyleLee, J. (2022). Impact of Staff Localization on Turnover: The Role of a Foreign Subsidiary CEO. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100402