Service Orientation and Customer Performance: Triad Perspectives of Sales Managers, Sales Employees, and Customers

Abstract

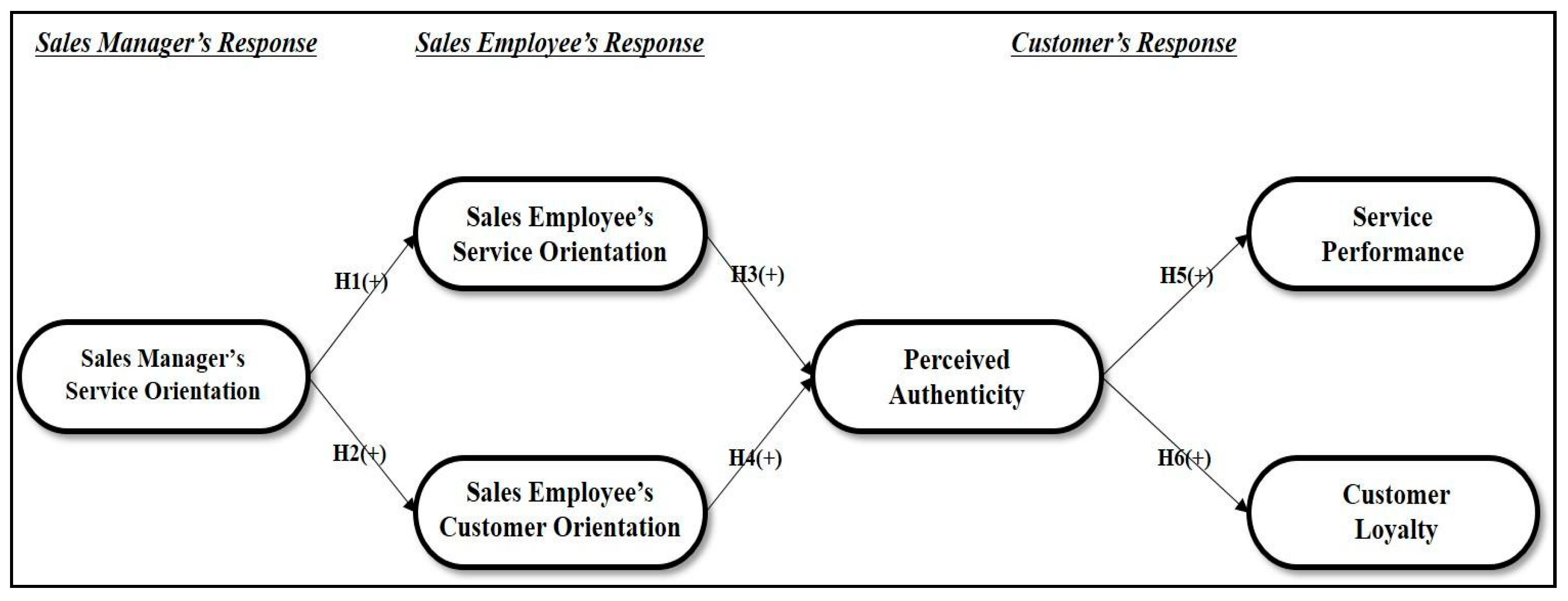

1. Introduction

- Does the service orientation of department store managers affect the individual-level service and customer orientation of sales employees?

- Do sales employees’ service and customer orientation positively impact customers to perceive service authenticity, thus resulting in effective service performance and customer loyalty?

2. Literature Overview and Derivation of Hypotheses

2.1. Service Orientation

2.2. Customer Orientation

2.3. Perceived Authenticity

2.4. Understanding Customer Performance: Service Performance and Customer Loyalty

2.5. Customer Loyalty

2.6. Research Model

2.7. Hypotheses

2.7.1. Relationship between Sales Managers’ and Employees’ Service Attitudes

2.7.2. Sales Employees’ Service and Customer Orientation and Perceived Authenticity

2.7.3. Perceived Authenticity and Customer Performance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Sampling Procedure and Data Collection

3.3. Validity and Reliability

4. Results

4.1. Hypothesis Testing

4.2. Additional Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- I treat each customer as if they were my only customer.

- My job is to sell a product, not deal with post-sale problems a buyer might encounter (reversed).

- The amount of money involved determines the attention I devote to a customer (reversed).

- The amount of time and number of calls required to obtain a sale are unimportant.

- I consider myself very customer oriented.

- I think customer interaction contributes to my personal development in this company.

- I enjoy interacting with customers.

- I always have the customers’ best interests in mind.

- Customer orientation is very important within my job.

- Sales employees in the shop seemed phony or fake (reversed).

- The sales employee said things that made me think they were not expressing their true thoughts (reversed).

- The sales employee had a fake smile (reversed).

- The sales employees understand the specific needs of customers.

- The sales employees can “put themselves in the customers’ place”.

- The employees do more than what is expected for customers.

- The employees deliver an excellent service quality that is difficult to find in other shops.

- If possible, I will return to this shop in the future.

- I will recommend this shop to other people.

- I will warn people about this shop.

References

- Veloso, C.M.; Ribeiro, H.; Alves, S.R.; Fernandes, P.O. Determinants of customer satisfaction and loyalty in the traditional retail service. Econ. Soc. Dev. (Book Proc.) 2017, 15, 470–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulou, I.; Petrou, A. Service quality and store performance: Some evidence from Greece. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2005, 15, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, M.F.; Sosianika, A. Retail service quality scale in the context of Indonesian traditional market. Int. Bus. Glob. 2018, 21, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.; Gaynor, M.; Morton, F.S. Do increasing markups matter? Lessons from empirical industrial organization. J. Econ. Perspect. 2019, 33, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, A.; He, Z.; West, D.S. An empirical analysis of tenant location patterns near department stores in planned regional shopping centers. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.C.; Heyman, J.E. We’ve shopped before: Exploring instructions as an influence on mystery shopper reporting. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanczyk-Hugiet, E.; Licharski, J.M.; Piorkowska, K. The dynamics of interfirm relationships along the industry life cycle: Theoretical background and conceptual framework. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2019, 18, 767–792. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, S.S.; Reddy, A.V. A conceptual study of mystery shopping as an ancillary method for customer surveys. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2016, 16, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, Y.; Rhie, J. The relationship between emotional labor status and workplace violence among toll collectors. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 29, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wen, C.; George, B.; Prybutok, V.R. Consumer heterogeneity, perceived value, and repurchase decision-making in online shopping: The role of gender, age, and shopping motives. J. Electron. Com. Res. 2016, 17, 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, R.D.; Tseng, H.C.; Lee, Y.C. Impact of service orientation on frontline employee service performance and consumer response. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2010, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.J.; Kranzler, A.; Parker, S.J.; Kash, V.M.; Weissberg, R.P. The complementary perspectives of social and emotional learning, moral education, and character education. In Handbook of Moral and Character Education; Nucci, L., Narvaez, D., Krettenauer, T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 248–266. [Google Scholar]

- Mangus, S.M.; Bock, D.E.; Jones, E.; Folse, J.A.G. Gratitude in buyer-seller relationships: A dyadic investigation. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2017, 37, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, R.A.; Bush, A.J. Exploring buyer-seller dyadic perceptions of technology and relationships: Implications for sales 2.0. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2016, 10, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, S.; Iacobucci, D. Antecedents and consequences of adaptive selling confidence and behavior: A dyadic analysis of salespeople and their customers. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; McFarland, R.G.; Kwon, S.; Son, S.; Griffith, D.A. Understanding governance decisions in a partially integrated channel: A contingent alignment framework. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sias, P.M. Organizing Relationships: Traditional and Emerging Perspectives on Workplace Relationships; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, S.M.; Chory, R.M.; Craw, E.S.; Jones, H.E. Blended work/life relationships: Organizational communication involving workplace peers, friends, and lovers. Commun. Res. Trends. 2021, 40, 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah, M.I.; Othman, A.K.; Hassan, F. Elucidating salespeople’s market orientation, proactive service behavior and organizational culture in the B2B banking sector: A Malaysian perspective. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1033–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroise, L.; Prim-Allaz, I.; Teyssier, C. Financial performance of servitized manufacturing firms: A configuration issue between servitization strategies and customer-oriented organizational design. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 71, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.T.; Dubinsky, A.J.; Lim, C.U. Manufacturer support for a partially integrated channel in South Korea: Power-dependence vs. marketing effectiveness perspective. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2013, 30, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremler, D.D.; Gwinner, K.P. Customer-employee rapport in service relationships. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 3, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dolen, W.; De Ruyter, K.; Lemmink, J. An empirical assessment of the influence of customer emotions and contact employee performance on encounter and relationship satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A.S.; Enz, C.A. The role of emotions in service encounters. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Groth, M.; Paul, M.; Gremler, D.D. Are all smiles created equal? How emotional contagion and emotional labor affect service relationships. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkington, J.J.; Schneider, B. Some correlates of experienced job stress: A boundary role study. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 22, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienhart, J.R.; Gregoire, M.B.; Downey, R.G.; Knight, P.K. Service orientation of restaurant employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1992, 11, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, R.S.; Timmerman, J.E. Service orientation and performance: An organizational perspective. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartline, M.D.; Ferrell, O.C. The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.P.; Hegde, P.G. Employee attitude towards customers and customer care challenges in banks. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2004, 22, 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C.; Barrows, C.W. Service orientation: Antecedents, outcomes, and implications for hospitality research and practice. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 1413–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Müller, M.; Klarmann, M. When should the customer really be king? On the optimum level of salesperson customer orientation in sales encounters. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, E.; Deretti, S.; Kato, H.T. Linking organizational service orientation to retailer profitability: Insights from the service-profit chain. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popli, S.; Rizvi, I.A. Leadership style and service orientation: The catalytic role of employee engagement. J. Serv. Theor. Pract. 2017, 27, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellesson, M.; Salomonson, N. It takes two to interact–Service orientation, negative emotions, and customer phubbing in retail service work. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.W.; Tang, Y.Y. Promoting service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors in hotels: The role of high-performance human resource practices and organizational social climates. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.J.; Liang, R.D.; Tung, W.; Chang, C.S. Structural relationships among organisation service orientation, employee service performance, and consumer identification. Serv. Ind. J. 2008, 28, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. The effects of organizational service orientation on person-organization fit and turnover intent. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheysari, H.; Rasli, A.; Jamshidi, M.H.M.; Roghanian, P.; Haghkhah, A. Fostering market orientation and service orientation culture in banking industry. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 2, 12617–12625. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Singh, S.N.; Li, Y.J.; Mishra, S.; Ambrose, M.; Biernat, M. Effects of employees’ positive affective displays on customer loyalty intentions: An emotions-as-social-information perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamolampros, P.; Korfiatis, N.; Chalvatzis, K.; Buhalis, D. Job satisfaction and employee turnover determinants in high contact services: Insights from employees’ online reviews. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimun, S.; Fernandes, A.A.R. The mediation effect of customer satisfaction in the relationship between service quality, service orientation, and marketing mix strategy to customer loyalty. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Bahman Teimouri, R.; Kiliç, H.; Aghaei, I. Effects of service orientation on job embeddedness in hotel industry. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, K. Service orientation in delivery: Perspectives from employees, customers, and managers. Serv. Mark. Q. 2014, 35, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamaki, M.; Hakala, H.; Partanen, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. The performance impact of industrial services and service orientation on manufacturing companies. J. Serv. Theor. Pract. 2015, 25, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojasalo, J. Managing customer expectations in professional services. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2001, 11, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Singh, S.; Pathak, P. An exploratory study on factors contributing to job dissatisfaction of retail employees in India. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadi, M.; Suuroja, M. Training retail sales personnel in transition economies: Applying a model of customer-oriented communication. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2006, 13, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Leong, J.K.; Lee, Y. Effect of service orientation on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention of leaving in a casual dining chain restaurant. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, M.T.; Ready, K.J.; Embaye, A.B. The effects of employee recognition, pay, and benefits on job satisfaction: Cross country evidence. J. Bus. Econ. 2013, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, F.; Chen, T. Do performance approach-oriented individuals generate creative ideas? The roles of outcome instrumentality and task persistence. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner Beitelspacher, L.; Glenn Richey, R.; Reynolds, K.E. Exploring a new perspective on service efficiency: Service culture in retail organizations. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, R.; Weitz, B.A. The SOCO scale: A measure of the customer orientation of salespeople. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarideh, N. The investigation of effect of customer orientation and staff service-oriented on quality of service, customer satisfaction and loyalty in hyper star stores. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2016, 5, 1837–1841. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.K.; Song, H.J.; Lee, H.M.; Lee, S.; Bernhard, B.J. The impact of CSR on casino employees’ organizational trust, job satisfaction, and customer orientation: An empirical examination of responsible gambling strategies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, H.; Zare, A.; Nasiri, M.; Asdnzhad, M. Examine the relationship between customer orientation and organizational citizenship behavior. Landsc. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Khuwaja, U.; Ahmed, K.; Abid, G.; Adeel, A. Leadership and employee attitudes: The mediating role of perception of organizational politics. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1720066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Tavitiyaman, P.; Kim, W.G. The effect of management commitment to service on employee service behaviors: The mediating role of job satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, H.; Hwang, J. Sustainable growth for the self-employed in the retail industry based on customer equity, customer satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Saura, I.; Berenguer Contrí, G.; Cervera Taulet, A.; Moliner Velázquez, B. Relationships among customer orientation, service orientation and job satisfaction in financial services. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2005, 16, 497–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.B.; Grigoriou, N.; Fuxman, L.; Reisel, W.D.; Hack-Polay, D.; Mohr, I. A generational study of employees’ customer orientation: A motivational viewpoint in pandemic time. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. Authenticity. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 382–394. [Google Scholar]

- Southworth, S.S.; Ha-Brookshire, J. The impact of cultural authenticity on brand uniqueness and willingness to try: The case of Chinese brands and US consumers. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2016, 28, 724–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V.; O’Sullivan, M. Smiles when lying. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X. Existential authenticity and destination loyalty: Evidence from heritage tourists. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, A.T.; Paul, M. Is this smile for real? The role of affect and thinking style in customer perceptions of frontline employee emotion authenticity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Sung, B.; Phau, I.; Lim, A. Communicating authenticity in packaging of Korean cosmetics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, M.; Hanks, L. Consumption authenticity in the accommodations industry: The keys to brand love and brand loyalty for hotels and Airbnb. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C. Multisensory brand experiences and brand love: Myth or reality? In Advances in Marketing, Customer Relationship Management, and E-Services; Rodrigues, C., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeer, A.A.; He, Y.; Abrar, M. The influence of brand experience on brand authenticity and brand love: An empirical study from Asian consumers’ perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 33, 1123–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, S.; Amos, C.; Fawcett, A.M.; Knemeyer, A.M.; Fawcett, S.E. Please clap! How customer service quality perception affects the authenticity of sustainability initiatives. J. Mark. Theor. Pract. 2017, 25, 396–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B.; Farrelly, F.J. The quest for authenticity in consumption: Consumers’ purposive choice of authentic cues to shape experienced outcomes. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Rubenstein, A.L.; Long, D.M.; Odio, M.A.; Buckman, B.R.; Zhang, Y.; Halvorsen-Ganepola, M.D.K. A meta-analytic structural model of dispositional affectivity and emotional labor. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 47–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelet, J.E.; Durrieu, F.; Lick, E. Label design of wines sold online: Effects of perceived authenticity on purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Liu, Y.; Namkung, Y. Effects of authentic atmospherics in ethnic restaurants: Investigating Chinese restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 23, 662–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, B.R. Effects of service authenticity, customer participation and customer-perceived service climate on customers’ service evaluation. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 33, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, J.E.; Combs, L.J. Product performance and consumer satisfaction: A new concept: An empirical study examines the influence of physical and psychological dimensions of product performance on consumer satisfaction. J. Mark. 1976, 40, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, K.; Lu, C.S. Organizational motivation, employee job satisfaction and organizational performance: An empirical study of container shipping companies in Taiwan. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2018, 3, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Chuang, A. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing employee service performance and customer outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Maxham III, J.G. Employee versus supervisor ratings of performance in the retail customer service sector: Differences in predictive validity for customer outcomes. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Shekhar, V.; Lassar, W.M.; Chen, T. Customer engagement behaviors: The role of service convenience, fairness and quality. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiri, L.A.; Guan Cheng, K.T.G.; Sambasivan, M.; Sidin, S.M. Integration of standardization and customization: Impact on service quality, customer satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; O’Donnell, M.; Robertson, D. Achieving employee commitment for continuous improvement initiatives. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015, 35, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburayya, A.; Marzouqi, A.A.; Alawadhi, D.; Abdouli, F.; Taryam, M. An empirical investigation of the effect of employees’ customer orientation on customer loyalty through the mediating role of customer satisfaction and service quality. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 2147–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adly, M.I. Modelling the relationship between hotel perceived value, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Customer orientation: Effects on customer service perceptions and outcome behaviors. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Wang, X.; Loureiro, S.M.C. The influence of brand experience and service quality on customer engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R.; Wymer, W.; Risk, A.; Taking, W. A risk worth taking: Perceived risk as moderator of satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness-to-pay premium price. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva Kanakaratne, M.; Bray, J.; Robson, J. The influence of national culture and industry structure on grocery retail customer loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Lang, C. Service employee dress: Effects on employee-customer interactions and customer-brand relationship at full-service restaurants. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Nguyen, M. Engaging and retaining customers with AI and employee service. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.H.W.; Rauschnabel, P.A.; Marimuthu, M.; Thurasamy, R.; Nguyen, B. Why do satisfied customers defect? A closer look at the simultaneous effects of switching barriers and inducements on customer loyalty. J. Serv. Theor. Pract. 2017, 27, 616–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Qin, Y.S.; Mitson, R. Engaging startup employees via charismatic leadership communication: The importance of communicating “vision, passion, and care”. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.Y.Y.; Tong, J.L.Y.; Lien, B.Y.H.; Hsu, Y.C.; Chong, C.L. Ethical work climate, employee commitment and proactive customer service performance: Test of the mediating effects of organizational politics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelham, A.M.; Kravitz, P. An exploratory study of the influence of sales training content and salesperson evaluation on salesperson adaptive selling, customer orientation, listening, and consulting behaviors. J. Strateg. Mark. 2008, 16, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.K.; Sachdeva, A.; Gupta, A. Treat employees like customers for an achievement culture: An intrinsic service quality perspective from Indian SMEs. J. Ind. Eng. Adv. 2017, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Tang, C. How does training improve customer service quality? The roles of transfer of training and job satisfaction. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.K.; Wu, M. Effects of online retailer after delivery services on repurchase intention: An empirical analysis of customers’ past experience and future confidence with the retailer. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Yoo, J.J.; Arnold, T.J. Service climate as a moderator of the effects of customer-to-customer interactions on customer support and service quality. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Busser, J.; Choi, H. Service climate: How does it affect turnover intention? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Chi, N.W.; Gremler, D.D. Emotion cycles in services: Emotional contagion and emotional labor effects. J. Serv. Res. 2019, 22, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, S.J.; Mun, S.; Whang, M. Measurement of emotional contagion using synchronization of heart rhythm pattern between two persons: Application to sales managers and sales force synchronization. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 200, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gursoy, D.; Chen, J.S. Validating a tourism development theory with structural equation modeling. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.M.; Duan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Lü, K.; Chen, S. The impact of online celebrity in livestreaming e-commerce on purchase intention from the perspective of emotional contagion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Fisk, G.M.; Mattila, A.S.; Jansen, K.J.; Sideman, L.A. Is “service with a smile” enough? Authenticity of positive displays during service encounters. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 96, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, K.S.; Coulter, R.A. Determinants of trust in a service provider: The moderating role of length of the relationship. J. Serv. Mark. 2002, 16, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, G.M.; Hampton, D.L. Relationship of professionalism, rewards, market orientation, and job satisfaction among medical professionals. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1042–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F. The microeconomics of customer relationships. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2006, 47, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Toya, K.; Lepak, D.P.; Hong, Y. Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olk, S.; Lindenmeier, J.; Tscheulin, D.K.; Zogaj, A. Emotional labor in a non-isolated service encounter–The impact of customer observation on perceived authenticity and perceived fairness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeren, D.; Kara, A. Effects of brand heritage on intentions to buy of airline services: The mediating roles of brand trust and brand loyalty. Sustainability 2020, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, T.W.; Peters, C.; Shelton, J. The consumer quest for authenticity: The multiplicity of meanings within the MG subculture of consumption. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjahjaningsih, E.; Ningsih, D.H.U.; Utomo, A.P. The effect of service quality and product diversity on customer loyalty: The role of customer satisfaction and word of mouth. J. Asian Fin. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. An exploratory study on drivers and deterrents of collaborative consumption in travel. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sias, P.M. Exclusive or Exclusory: Workplace Relationships, Ostracism, and Isolation. Problematic Relationships in the Workplace; Harden Fritz, J.M., Omdahl, B.L., Eds.; Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R.; Sheriff, K.; Owen, K. Conceptualising and measuring consumer authenticity online. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia-Palacios, L.; Pérez-López, R.; Polo-Redondo, Y. How situational circumstances modify the effects of frontline employees’ competences on customer satisfaction with the store. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.-Y.; Li, Q.-L. Research on the influence of brand authenticity of agricultural products on brand evangelism. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Social Sci. Ed.) 2020, 3, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Keillor, B.D.; Parker, R.S.; Pettijohn, C.E. Sales force performance satisfaction and aspects of relational selling: Implications for sales managers. J. Mark. Theor. Pract. 1999, 7, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.J.; Arnold, T.J. Customer orientation, engagement, and developing positive emotional labor. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 1272–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.J.; Arnold, T.J. Frontline employee authenticity and its influence upon adaptive selling outcomes. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2397–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsted, K. The service experience in two cultures: A behavioral perspective. J. Retailing. 1997, 73, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asubonteng, P.; McCleary, K.J.; Swan, J.E. SERVQUAL revisited: A critical review of service quality. J. Serv. Mark. 1996, 10, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.L.; Arnould, E.J.; Deibler, S.L. Consumers’ emotional responses to service encounters. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1995, 6, 34–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Agut, S.; Peiró, J.M. Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, J.E.; Oliver, R.L. Post-purchase communications by consumers. J. Retailing. 1989, 65, 516. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Cross-cultural research methods. In Environment and Culture, 4th ed.; Altman, I., Rapoport, A., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Tam, A.P.; Brauburger, A.L. Affective states and traits in the workplace: Diary and survey data from young workers. Motiv. Emot. 2002, 26, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazian, D. Demystifying authenticity in the sociology of culture. In Routledge Handbook of Cultural Sociology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kram, K.E.; Isabella, L.A. Mentoring alternatives: The role of peer relationships in career development. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 110–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S.; Balaji, M.S.; Yavas, U.; Babakus, E. Effects of frontline employee role overload on customer responses and sales performance: Moderator and mediators. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.E.; Luk, S.T.K. Interaction behaviors leading to comfort in the service encounter. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieseke, J.; Geigenmüller, A.; Kraus, F. On the role of empathy in customer-employee interactions. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sias, P.M.; Cahill, D.J. From coworkers to friends: The development of peer friendships in the workplace. West J. Com. 1998, 62, 273–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayighomog, S.W.; Araslı, H. Workplace spirituality—Customer engagement nexus: The mediated role of spiritual leadership on customer-oriented boundary-spanning behaviors. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 637–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, H.; Chen, P.J. Empowerment in hospitality organizations: Customer orientation and organizational support. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | N | % | Classification | N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department store branch | Trade center | 39 | 20.1 | Product category | Golf and outdoor | 48 | 24.7 |

| Mokdong | 39 | 20.1 | Cosmetics | 48 | 24.7 | ||

| Pankyo | 37 | 19.1 | Men’s fashion | 48 | 24.7 | ||

| Cheonho | 40 | 20.6 | Women’s fashion | 50 | 25.8 | ||

| Shinchon | 39 | 20.1 | Manager’s work experience | Under 3 years | 99 | 51.0 | |

| Manager’s gender | Man | 49 | 25.3 | 3–6 years | 36 | 18.6 | |

| Woman | 145 | 74.7 | 6–9 years | 17 | 8.8 | ||

| Sales employee’s gender | Man | 41 | 21.1 | Over 9 years | 42 | 21.6 | |

| Woman | 153 | 78.8 | Department store transaction periods of customers | Under 3 years | 83 | 42.8 | |

| Customer’s gender | Man | 87 | 22.4 | 3–6 years | 45 | 23.2 | |

| Woman | 301 | 77.6 | 6–9 years | 30 | 15.5 | ||

| Sales employee’s work experience | Under 3 years | 137 | 70.6 | Over 9 years | 36 | 18.6 | |

| 3–6 years | 40 | 20.6 | Shop transaction periods of customers | Under 3 years | 125 | 64.4 | |

| 3–6 years | 34 | 17.5 | |||||

| Over 6 years | 17 | 8.8 | 6–9 years | 20 | 10.3 | ||

| Over 9 years | 15 | 7.7 | |||||

| Item | Construct | St. Estimate | SE | CR | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M_SO1 | Manager’s service orientation | 0.874 | - | - | 0.745 | 0.938 | 0.929 |

| M_SO2 | 0.930 | 0.058 | 17.702 | ||||

| M_SO3 | 0.844 | 0.064 | 15.354 | ||||

| M_SO4 | 0.800 | 0.064 | 13.933 | ||||

| E_SO1 | Sales employee’s service orientation | 0.782 | - | - | 0.763 | 0.945 | 0.927 |

| E_SO2 | 0.850 | 0.088 | 13.288 | ||||

| E_SO3 | 0.946 | 0.083 | 15.223 | ||||

| E_SO4 | 0.908 | 0.085 | 14.512 | ||||

| E_CO1 | Sales employee’s customer orientation | 0.732 | - | - | 0.529 | 0.921 | 0.860 |

| E_CO2 | 0.677 | 0.106 | 10.575 | ||||

| E_CO3 | 0.685 | 0.123 | 8.376 | ||||

| E_CO4 | 0.810 | 0.131 | 8.882 | ||||

| E_CO5 | 0.725 | 0.120 | 8.061 | ||||

| C_SP1 | Service performance | 0.870 | - | - | 0.806 | 0.960 | 0.948 |

| C_SP2 | 0.888 | 0.042 | 25.266 | ||||

| C_SP3 | 0.919 | 0.060 | 18.212 | ||||

| C_SP4 | 0.914 | 0.058 | 18.098 | ||||

| C_AUT1 | Perceived authenticity | 0.771 | - | - | 0.794 | 0.921 | 0.914 |

| C_AUT2 | 0.940 | 0.082 | 14.836 | ||||

| C_AUT3 | 0.950 | 0.079 | 14.981 | ||||

| C_LYL1 | Customer loyalty | 0.951 | - | - | 0.892 | 0.960 | 0.965 |

| C_LYL2 | 0.939 | 0.041 | 24.813 | ||||

| C_LYL3 | 0.943 | 0.043 | 24.410 |

| Construct | M | St. d | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manager’s service orientation (1) | 6.294 | 1.094 | 1 | 0.280 ** | 0.131 | 0.245 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.178 * | 0.163 * |

| Sales employee’s service orientation (2) | 5.711 | 1.108 | 1 | 0.365 | 0.303 ** | 0.242 ** | 0.216 ** | 0.119 | |

| Sales employee’s customer orientation (3) | 6.279 | 0.772 | 1 | 0.288 ** | 0.222 ** | 0.153 * | 0.195 ** | ||

| Service performance (4) | 4.445 | 0.776 | 1 | 0.639 ** | 0.622 ** | 0.116 | |||

| Perceived authenticity (5) | 5.776 | 0.908 | 1 | 0.708 ** | 0.195 ** | ||||

| Customer’s loyalty (6) | 6.085 | 0.926 | 1 | 0.188 ** | |||||

| Customer’s shop transaction periods (7) | 3.052 | 3.579 | 1 |

| Hypothesis | Path | St. Estimate | SE | CR | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1(+) | Manager’s service orientation → Sales employee’s service orientation | 0.166 * | 0.051 | 2.018 | Supported |

| H2(+) | Manager’s service orientation → Sales employee’s customer orientation | 0.297 ** | 0.065 | 3.867 | Supported |

| H3(+) | Sales employee’s service orientation → Perceived authenticity | 0.194 ** | 0.087 | 2.575 | Supported |

| H4(+) | Sales employee’s customer orientation → Perceived authenticity | 0.191 * | 0.128 | 2.385 | Supported |

| H5(+) | Perceived authenticity → Service performance | 0.665 ** | 0.071 | 8.727 | Supported |

| H6(+) | Perceived authenticity → Customer loyalty | 0.753 ** | 0.082 | 10.417 | Supported |

| Control | Customer’s shop transaction periods → Service performance | 0.049 | 0.012 | 0.949 | N/A |

| Customer’s shop transaction periods → Customer loyalty | −0.008 | 0.011 | −0.145 | N/A |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yi, H.-T.; Lee, M.; Park, K. Service Orientation and Customer Performance: Triad Perspectives of Sales Managers, Sales Employees, and Customers. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100373

Yi H-T, Lee M, Park K. Service Orientation and Customer Performance: Triad Perspectives of Sales Managers, Sales Employees, and Customers. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(10):373. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100373

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Ho-Taek, MinKyung Lee, and Kyungdo Park. 2022. "Service Orientation and Customer Performance: Triad Perspectives of Sales Managers, Sales Employees, and Customers" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 10: 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100373

APA StyleYi, H.-T., Lee, M., & Park, K. (2022). Service Orientation and Customer Performance: Triad Perspectives of Sales Managers, Sales Employees, and Customers. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100373