Crafting Life Stories in Photocollage: An Online Creative Art-Based Intervention for Older Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Creative Arts Therapies with Older Adults

1.2. Tele Psychotherapies and Tele-CAT for Older Adults

1.3. An Online Creative Process with Photocollages Based on Dignity Therapy

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. The Creative Process for Online Photocollage

2.4. Data Analysis

| Stage in the Process | Main Goals | Method and Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Introductory call to participants to introduce the study and its aims |

|

|

| Session 1: Turning Points |

|

|

| Session 2: Values and Legacy for Future Generations |

|

|

| Session 3: Future Perspectives and Wisdom |

|

|

| Sending a hard copy of the photocollages |

|

|

3. Results

3.1. Experiencing the Creative Process of Photocollages: “This Is True Art What We Are Doing Now”

3.1.1. The Photographs as Projective Stimulus for Personal Content

I am looking at the (photographs), the bicycle, the telephone, the twins, the building. It gives me, it gives me a sense that I am way in the past. I didn’t even remember these things. All the memories you drew from me, all the memories in my head. You really opened them up. Without (this process) I would have never accessed them … I am surprised. You surprised me. It’s a different aspect of nostalgia. I thought we would focus on (a different part of) my life story. And suddenly, you threw me back to after the army.

The landscape that I see there, look, look, it’s not only the desert, a crater. There are changes there. Look at the crater, the sand, the earth, the color, the granite. This is all a landscape of how the world changes. This is something. Look at the sand, yellowish-gray in color, the crumbling tree trunk. Thousands of years. This is life, exactly like life. We age, crumble. Crumble and finish. It’s the same, the same. Like a mirror (of life).

This one (this photo) for me represents that period in life in which my husband was far away. I told him he should buy me a cow. Because here, in our village, there was a cheese factory, where you could buy milk, and there was this dairy man and so I brought my milk, once a month, and the dairy man made me the cheese. I kept some for my children and the rest I sold so I managed, I was able to provide food for my children.

Well, I think the idea of showing pictures in general to evoke whatever the topic is, is a very good idea. I think it leads, for me at least, to an enjoyable experience. With an interview, you sort of have preconceived ideas about what it is you want to know. But with the pictures, it allowed me to be the one to more or less lead where we’re going to go. I didn’t feel invaded. I didn’t feel like sort of attacked in any way. You didn’t invade my privacy. I felt safe.

3.1.2. Engaging in an Embodied Experience

Photographs speak. The feeling from this photo, for instance, this dad with his child, you can talk for half an hour but it’s an idea. This is felt, you touch, you touch the emotion with your hand. I find it stimulating, much more than a dialogue, in the sense that photography gives you the emotion. And the emotion, you work with memory, with the reflection. That way, it draws out the true things one has inside.

Yes, this is part of my life. The first time I went to the beach, I felt the foam in my entire body, not just my feet, I don’t know how to describe it. When the waves break at the shore, it’s like an earthquake on the shore. I felt it, I got emotional. It wasn’t something I had experienced before. The first time I went to the beach I was five maybe six years old.

I am sweating as we are talking about it (future desires). I’m not working hard but just thinking about it makes me sweat. I don’t know if this is natural … it’s a very exciting, emotional topic. It lets me dream, makes me sweat!

3.1.3. Artistic Enjoyment

It is very beautiful. It reminds me of the way to Jericho, the way to the Dead Sea… The desert, the desert that we see from the amphitheater in Mount Scopus. They (the photos) are all so beautiful, they are all so beautiful. They are all special. They are full of substance, it’s wonderful (laughs).

3.1.4. Challenges Associated with the Process

Look, I, it’s probably not right for me, this collage. Because I, I like to use words, and, and not something that is so abstract. I can tell you what the, what can be learned from my story. And if you want to, add words to it.

It did not cover life, not a complete life, and not an incomplete one, not even the main chapters. In the pictures there were jumps from, from event to event and from period to period. And there was no order, no logical order. I felt, as I told you, that it was strained. And there were all sorts of holes left in my biography, in my past, that were not covered.

It’s harder to link it, philosophically, to points in my life, much harder. What attracts me more is the arrangement, I mean, the perspective, more than connecting life segments to the photographs. I’m making this, the connection, because that’s … we started with that. I mean, you led to it, but it does not come naturally, a little more strained because I understand that there is a purpose to the task of choosing the photographs, it is difficult for me.

3.2. Collecting Life Experiences through the Art Product of Photocollage: “Everything Is Here, Life, Everything. Outstanding.”

I like this one (this photograph, as the center of my collage) very much, this one of this father holding his child. I like it very much. The importance of a father in the family, especially now when fathers either are too busy working or are unprepared. I think a man who does his job as a father well gives something very valuable to his family. I find this very important.

The cross, let’s put it here or above. Above, above because it’s the most important of all. It covers everything else. That’s it, move the bird. The bird needs to move. That’s it, above the father. It’s as if it embraces everything.

It’s a promise of loyalty. Because we felt very united, engaged in this thing. You know, also later through the years, when I woke up in the morning, I immediately found my husband’s hand holding mine and then we woke up and did what we had to, but first thing, he held my hand, you know? Therefore, it was very important for us to have this first good morning that we gave each other with our hands, you know? And I am moved when I see these hands holding each other because I spent every morning knowing I had someone who loved me close to me. And I miss him a lot now.

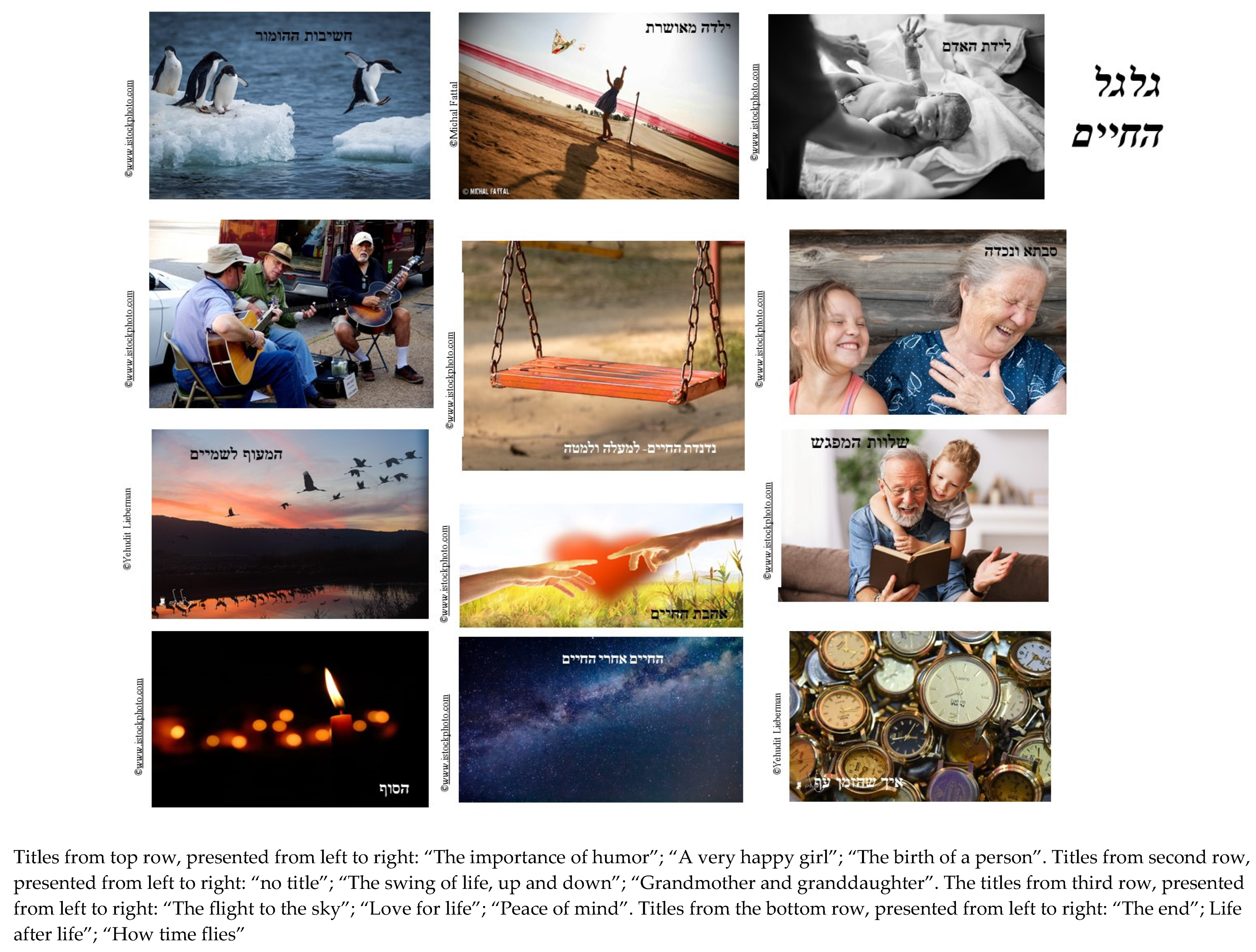

Grandmother and granddaughter. Here I would also put the picture of the grandfather and son, the grandson. Below. A very soothing picture, of a grandfather and grandson talking to each other. I do not know whether to call it the “Generation gap”, or something like that.

The (photograph of the) “flight to the sky”, and the clocks, I would say “how time flies” (...) Yes, this is a good place, at the bottom right side (of the collage). And the candle (at the left side of collage), that is the end. I would like (it) to be in my bedroom, surrounded by my family. And close friends. And they should sing me songs that I like. I could go peacefully.

This is the age where I approach the end. My granddaughter on the other hand has just begun her life. I really spend quality time with her. I play with her, tell her stories, read to her, and play. I enjoy her … there is such serenity in this picture. Peace. Okay, you can just (title it) “Peace of mind”.

3.3. The Therapeutic Environment: “I Feel like Hugging You”

3.3.1. Experiencing the Online Setting

I’m not used to the computer. I don’t have a computer at home. And it’s as if I’m talking to a wall I don’t know, do you understand? If it was personal, if I met you and we spoke, that’s something else, but to speak to the computer, it makes me feel uncomfortable. When I speak to someone, I see them personally and it makes me feel good.

3.3.2. Participant Interactions with the Therapists

I feel like hugging you, because, this evening, you gave me the joy to express things I had inside. I would wait impatiently for you to call me, I waited, I was impatient… I would like to meet you again; you gave me joy.

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shafir, T.; Orkibi, H.; Baker, F.A.; Gussak, D.; Kaimal, G. Editorial: The state of the art in creative arts therapies. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P. Arts Therapies: A Revolution in Healthcare, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- de Witte, M.; Orkibi, H.; Zarate, R.; Karkou, V.; Sajnani, N.; Malhotra, B.; Ho, R.T.H.; Kaimal, G.; Baker, F.A.; Koch, S.C. From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czamanski-Cohen, J.; Weihs, K.L. The bodymind model: A platform for studying the mechanisms of change induced by art therapy. Arts Psychother. 2016, 51, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malchiodi, C.A. Expressive Therapies; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pendzik, S. Drama therapy and the invisible realm. Drama Ther. Rev. 2018, 4, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, A.; Orkibi, H. Concretization as a mechanism of change in psychodrama: Procedures and benefits. Front. Psychol. 2021, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalsky, R.; Raz, N.; Keisari, S. An Introduction to Psychotherapeutic Playback Theatre: The Hall of Mirrors on Stage; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Landy, R. Drama therapy and distancing: Reflections on theory and clinical application. Arts Psychother. 1996, 23, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.L. Psychodrama, First Volume; Beacon House: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. Acts of Service: Spontaneity, Commitment, Tradition in the Nonscripted Theatre; Tusitala: New Paltz, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv, D. Trust the process: A new scientific outlook on psychodramatic spontaneity training. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Orkibi, H. Creative adaptability: Conceptual framework, measurement, and outcomes in times of crisis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, S.; Gumley, A.; Turnbull, S. Safety, play, enablement, and active involvement: Themes from a Grounded Theory study of practitioner and client experiences of change processes in Dramatherapy. Arts Psychother. 2017, 55, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keisari, S.; Gesser-Edelsburg, A.; Yaniv, D.; Palgi, Y. Playback theatre in adult day centers: A creative group intervention for community-dwelling older adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandel, S.L.; Johnson, D.R. Waiting at the Gate: Creativity and Hope in the Nursing Home; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Keisari, S.; Palgi, Y.; Yaniv, D.; Gesser-Edelsburg, A. Participation in life-review playback theater enhances mental health of community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, R.L. Art therapies and dementia care: A systematic review. Dementia 2012, 11, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasca, E.C.; Ferreira, R.C.; Santana, C.L.A.; Forlenza, O.V.; Dos Santos, G.D.; Brum, P.S.; Nunes, P.V. Art therapy as an adjuvant treatment for depression in elderly women: A randomized controlled trial. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2018, 40, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunphy, K.; Baker, F.A.; Dumaresq, E.; Carroll-Haskins, K.; Eickholt, J.; Ercole, M.; Kaimal, G.; Meyer, K.; Sajnani, N.; Shamir, O.Y.; et al. Creative arts interventions to address depression in older adults: A systematic review of outcomes, processes, and mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Bai, Z.G.; Bo, A.; Chi, I. A systematic review and meta-analysis of music therapy for the older adults with depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masika, G.M.; Yu, D.S.F.; Li, P.W.C. Visual art therapy as a treatment option for cognitive decline among older adults. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1892–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masika, G.M.; Yu, D.S.F.; Li, P.W.C. Can visual art therapy be implemented with illiterate older adults with mild cognitive impairment? A pilot mixed-method randomized controlled trial. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2021, 34, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; D’Ippolito, M.; Iacona, E.; Zamperini, A.; Mencacci, E.; Chochinov, H.M.; Grassi, L. Dignity therapy and the past that matters: Dialogues with older people on values and photos. J. Loss Trauma 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, J. Using personal snapshots and family pothographs as therapy tools: The “why, what, and how” of photo therapy. PSICOART 2010, 1, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallings, J.W. Collage as a therapeutic modality for reminiscence in patients with dementia. Art Ther. 2010, 27, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, R.L. At the confluence of memory and meaning—Life review with older adults and families: Using narrative therapy and the expressive arts to re-member and re-author stories of resilience. Fam. J. 2005, 13, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravid-Horesh, R.H. “A temporary guest”: The use of art therapy in life review with an elderly woman. Arts Psychother. 2004, 31, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassa, A.; Harel, D. People with dementia as ‘spect-actors’ in a musical theatre group with performing arts students from the community. Arts Psychother. 2019, 65, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisari, S. Expanding the role repertoire while aging: A drama therapy model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryhill, M.B.; Culmer, N.; Williams, N.; Halli-Tierney, A.; Betancourt, A.; Roberts, H.; King, M. Videoconferencing psychotherapy and depression: A systematic review. Telemed. E-Health 2019, 25, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keisari, S.; Sajnani, N.; Harel, D. Creative arts therapies to enhance mental health over the course of aging: Research and implications. Innovation in Aging. 2021, 5, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, S.; Yeshua-Katz, D.; Cohn-Schwartz, E.; Aharonson-Daniel, L.; Sarid, O.; Clarfield, A.M. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a group intervention via Zoom to relieve loneliness and depressive symptoms among older persons during the COVID-19 outbreak. Internet Interv. 2021, 24, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.S.; Shillair, R.; Cotten, S.R.; Winstead, V.; Yost, E. Getting Grandma Online: Are tablets the answer for increasing digital inclusion for older adults in the U.S.? Educ. Gerontol. 2015, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- van Dijk, S.D.M.; Bouman, R.; Folmer, E.H.; den Held, R.C.; Warringa, J.E.; Marijnissen, R.M.; Voshaar, R.C.O. (Vi)-rushed into online group schema therapy based day-treatment for older adults by the COVID-19 outbreak in the Netherlands. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.G.; Hegel, M.T.; Marti, C.N.; Marinucci, M.L.; Sirrianni, L.; Bruce, M.L. Telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed low-income homebound older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 22, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.G.; Pepin, R.; Marti, C.N.; Stevens, C.J.; Bruce, M.L. Improving social connectedness for homebound older adults: Randomized controlled trial of tele-delivered behavioral activation versus tele-delivered friendly visits. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavingia, R.; Jones, K.; Ashgar-Ali, A.A. A systematic review of barriers faced by older adults in seeking and accessing mental health care. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2020, 26, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.; Maharani, A.; Chandola, T.; Todd, C.; Pendleton, N. The longitudinal relationship between loneliness, social isolation, and frailty in older adults in England: A prospective analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e70–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; McGarrigle, C.A.; Carey, D.; Kenny, R.A. Correction to: Social capital and quality of life among urban and rural older adults. Quantitative Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1399–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.G.; Wilson, N.L.; Sirrianni, L.; Marinucci, M.L.; Hegel, M.T. Acceptance of home-based telehealth Problem-Solving Therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults: Qualitative interviews with the participants and aging-service case managers. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McClellan, M.J.; Florell, D.; Palmer, J.; Kidder, C. Clinician telehealth attitudes in a rural community mental health center setting. J. Rural Ment. Healthy 2020, 44, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, S.L.; Miller, C.J.; Lindsay, J.A.; Bauer, M.S. A systematic review of providers’ attitudes toward telemental health via videoconferencing. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsmon, A.; Pendzik, S. The clinical use of digital resources in drama therapy: An exploratory study of well-established practitioners. Drama Ther. Rev. 2020, 6, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancalani, G.; Franco, C.; Guglielmin, M.S.; Moretto, L.; Orkibi, H.; Keisari, S.; Testoni, I. Tele-psychodrama therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: Participants’ experiences. Arts Psychother. 2021, 75, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubala, A.; Kennell, N.; Hackett, S. Art Therapy in the Digital World: An Integrative Review of Current Practice and Future Directions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordova, S.; Keisari, S. ‘Great red anemone and its beautiful black pollens’: On tele-drama therapy sessions with older adults in times of COVID-19. Drama Ther. Rev. 2020, 6, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, G.; Mensinger, J.L.; Carroll-Haskins, K. Outcomes of collage art-based and narrative self-expression among home hospice caregivers. Int. J. Art Ther. 2020, 25, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, T.; Hartzell, E. A Comparison of adults’ responses to collage versus drawing in an initial art-making session. Art Therapy 2016, 33, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Zimet, G. The “Metaphorical Collage” as a Research Tool in the Field of Education. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, G.; Scotti, V. Snipping, gluing, writing: The properties of collage as an arts-based research practice in art therapy. Art Ther. 2014, 31, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.N. The life review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry 1963, 26, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. The Life Cycle Completed; Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, J.P. Praticare le mediazioni in gruppi terapeutici. In Praticare Le Mediazioni in Gruppi Tera-Peutici; Borla: Roma, Italy, 2005; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Blix, B.H.; Berendonk, C.; Clandinin, D.J.; Caine, V. The necessity and possibilities of playfulness in narrative care with older adults. Nurs. Inq. 2021, 28, e12373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, W.L. The importance of being ironic: Narrative openness and personal resilience in later life. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Hack, T.; Hassard, T.; Kristjanson, L.J.; McClement, S.; Harlos, M. Dignity and Psychotherapeutic Considerations in End-of-Life Care. J. Palliat. Care 2004, 20, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Hack, T.; McClement, S.; Kristjanson, L.; Harlos, M. Dignity in the terminally ill: A developing empirical model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Hack, T.; Hassard, T.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Mcclement, S.; Harlos, M. Dignity Therapy: A novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 5520–5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Julião, M. Dignity, memory, and final wishes of dying children. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Bingaman, K.A.; D’Iapico, G.; Marinoni, G.L.; Zamperini, A.; Grassi, L.; Nanni, M.G.; Vacondio, P. Dignity as wisdom at the end of life: Sacrifice as value emerging from a qualitative analysis of generativity documents. Pastor. Psychol. 2019, 68, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Baroni, V.; Iacona, E.; Zamperini, A.; Keisari, S.; Ronconi, L.; Grassi, L. The sense of dignity at the end of life: Reflections on lifetime values through the family photo album. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouse, S. Collage: Integrating the torn pieces. In Grief and the Expressive Arts; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 186–197. ISBN 9780203798447. [Google Scholar]

- Renzenbrink, I. Photographic Metaphor. In Grief and the expressive arts; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 198–201. ISBN 9780203798447. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Alonso, B.; De Luna, I.B. Narratives of loss: Exploring grief through photography. Qual. Stud. 2021, 6, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. Interview Views: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, P. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, J.A.; Boydell, K.M. Arts-based research and knowledge translation: Some key concerns for health-care professionals. J. Interprof. Care 2012, 26, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, H.J.; George, J. Cognitive assessment in the elderly: A review of clinical methods. QJM 2007, 100, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keisari, S.; Palgi, Y. Life-crossroads on stage: Integrating life review and drama therapy for older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, D.P. The psychology of life stories. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.R.; Carstensen, L.L. Time counts: Future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychol. Aging 2002, 17, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; Ancona, D.; Ronconi, L. The Ontological Representation of Death. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2015, 71, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Facco, E.; Perelda, F. Toward a new eternalist paradigm for afterlife studies: The case of the near-death experiences argument. World Futures 2017, 73, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, J. PhotoTherapy Techniques in Counselling and Therapy—Using Ordinary Snapshots and Photo-Interactions to Help Clients Heal Their Lives. Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 2004, 17, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, S.H. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 2307-0919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, A.; Robb, M. (Re)considering psychological constructs: A thematic synthesis defining five therapeutic factors in group art therapy. Arts Psychother. 2017, 55, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolk, N.; Barak, A.; Yaniv, D. Different shades of beauty: Adolescents’ perspectives on Drawing from observation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Leading a meaningful life at older ages and its relationship with social engagement, prosperity, health, biology, and time use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bion, W.R. Elements of Psycho-Analysis; Heinemann: London, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof, G.J. Life review and life-Story work. In The Encyclopedia of Adulthood and Aging; Wiley: Malden, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Slatman, S. In search of the best evidence for life review therapy to reduce depressive symptoms in older adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2019, 26, e12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malkinson, R.; Bar-Tur, L. REBT with Ageing Populations. In REBT with Diverse Client Problems and Populations; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 341–358. [Google Scholar]

- Etzelmueller, A.; Radkovsky, A.; Hannig, W.; Berking, M.; Ebert, D.D. Patient’s experience with blended video- and internet based cognitive behavioural therapy service in routine care. Internet Interv. 2018, 12, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran, A.L. Understanding the role of transportation-related social interaction in travel behavior and health: A qualitative study of adults with disabilities. J. Transp. Healthy 2020, 19, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palgi, Y.; Shrira, A.; Ring, L.; Bodner, E.; Avidor, S.; Bergman, Y.; Cohen-Fridel, S.; Keisari, S.; Hoffman, Y. The loneliness pandemic: Loneliness and other concomitants of depression, anxiety and their comorbidity during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Kropf, N.; Campbell, R.; Parker, M. A systematic review of dyadic approaches to reminiscence and life review among older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ounalli, H.; Mamo, D.; Testoni, I.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Caruso, R.; Grassi, L. Improving Dignity of Care in Community-Dwelling Elderly Patients with Cognitive Decline and Their Caregivers. The Role of Dignity Therapy. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; Falletti, S. Il volontariato nelle cure palliative: Religiosità, rappresentazioni esplicite della morte e implicite di Dio tra deumanizzazione e burnout. Psicol. DELLA Salut. 2016, 2, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochinov, H.M. Dignity Therapy: Final Words for Final Days; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780195176216. [Google Scholar]

- Testoni, I.; Piscitello, M.; Ronconi, L.; Zsák, É.; Iacona, E.; Zamperini, A. Death Education and the Management of Fear of Death Via Photo-Voice: An Experience Among Undergraduate Students. J. Loss Trauma 2019, 24, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Israeli Participants | Italian Participants | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range) | 83.92 (80–92) | 84 (78–88) | 83.96 (78–92) |

| Gender | 6 females | 8 females | 58.33% female |

| Place of birth | 3 in Israel; 4 in N. America; 4 in Europe; 1 in Asia | All were from Italy | 37.5% had immigrated (only Israeli participants) |

| Marital status | 1 married; 2 divorced; 9 widowed | 5 married; 7 widowed | 25% married |

| Education | 4 with a high school education; 8 with a college education | 6 with a primary school education; 6 with high school education | 25% with a primary school education; 41.66% with a high school education; 33.33% with a college education |

| Religiosity | 8 defined themselves as secular; 4 as religious | 2 defined themselves secular; 10 religious | 58.33% defined themselves as religious |

| Religion | 11 secular Jewish; 1 atheist | All the participants considered themselves Catholic | 45.83% defined themselves as secular Jewish; 50% Catholic; 4.16% atheist. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keisari, S.; Piol, S.; Elkarif, T.; Mola, G.; Testoni, I. Crafting Life Stories in Photocollage: An Online Creative Art-Based Intervention for Older Adults. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12010001

Keisari S, Piol S, Elkarif T, Mola G, Testoni I. Crafting Life Stories in Photocollage: An Online Creative Art-Based Intervention for Older Adults. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeisari, Shoshi, Silvia Piol, Talia Elkarif, Giada Mola, and Ines Testoni. 2022. "Crafting Life Stories in Photocollage: An Online Creative Art-Based Intervention for Older Adults" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12010001

APA StyleKeisari, S., Piol, S., Elkarif, T., Mola, G., & Testoni, I. (2022). Crafting Life Stories in Photocollage: An Online Creative Art-Based Intervention for Older Adults. Behavioral Sciences, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12010001