Abstract

In the wake of a global economic recession secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic, this scoping review seeks to summarize the current quantitative research on the impact of economic recessions on depression, anxiety, traumatic disorders, self-harm, and suicide. Seven research databases (PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science: Core Collection, National Library of Medicine PubMed, PubMed Central, and Google Scholar) were searched for keywords returning 3412 preliminary results published since 2008 in Organisation for Economic Coordination and Development (OECD)nations. These were screened by both authors for inclusion/exclusion criteria resulting in 127 included articles. Articles included were quantitative studies in OECD countries assessing select mental disorders (depression, anxiety, and trauma-/stress-related disorders) and illness outcomes (self-harm and suicide) during periods of economic recession. Articles were limited to publication from 2008 to 2020, available online in English, and utilizing outcome measures specific to the disorders and outcomes specified above. A significant relationship was found between periods of economic recession and increased depressive symptoms, self-harming behaviour, and suicide during and following periods of recession. Results suggest that existing models for mental health support and strategies for suicide prevention may be less effective than they are in non-recession times. It may be prudent to focus public education and medical treatments on raising awareness and access to supports for populations at higher risk, including those vulnerable to the impacts of job or income loss due to low socioeconomic status preceding the recession or high levels of financial strain, those supporting others financially, approaching retirement, and those in countries with limited social safety nets. Policy makers should be aware of the potential protective nature of unemployment safeguards and labour program investment in mitigating these negative impacts. Limited or inconclusive data were found on the relationship with traumatic disorders and symptoms of anxiety. In addition, research has focused primarily on the working-age adult population with limited data available on children, adolescents, and older adults, leaving room for further research in these areas.

Keywords:

economic recession; mental health; depression; anxiety; trauma; suicide; mortality; scoping review 1. Introduction

Since the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic was declared by the WHO on 11 March 2020, world economies have been hit by numerous unprecedented market closures, supply chain, trade, and finance interruptions leading to a global economic recession. The World Bank reported in June 2020 that the global economy would shrink by 5.2% in 2020—the deepest recession since World War II—and that economic activity among advanced economies was anticipated to shrink 7% [1]. Per capita incomes were expected to decline by 3.6%, tipping millions of people into extreme poverty with the most severe impacts in countries where the pandemic has been the most severe and there is heavy reliance on global trade, tourism, commodity exports, and external financing [1]. The Global Economic Prospects for 2020 warned of a lost decade, or more, of per-capita income gains and concern that cumulative factors, including massive public and private debt and a breakdown in education, will lead to a prolonged deterioration in economic prospects [2]. The 2021 Global Economic Prospects report predicts an expansion of 5.6% in 2021, the fastest post-recession pace in 80 years; however, global output will remain about 2% lower than pre-pandemic projections [3]. In this reality, the international community and governments around the world are looking to reboot their economies and put the recession of the COVID-19 pandemic behind us. Unfortunately, with history as our teacher, the repercussions of economic recessions are numerous, and the societal impacts are pervasive. There have been discussions throughout the pandemic about the impact of public health restrictions and the traumas of the pandemic itself on the mental health of our society; however, limited attention has been paid to the impacts of economic recessions on mental health.

Disaster mental health research has shown, over decades of research from the 1940s to the present, that following both natural and human-made disasters, specific psychological problems have been seen to occur, such as depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders [4,5,6]. Outcomes measured in the literature range from the presentation of increased symptoms to diagnoses of a psychiatric disorder, such as Major Depressive Disorder, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), or one of several anxiety disorders, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [4]. Per the DSM5, symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) include persistently depressed mood, diminished interest or pleasure in activities, change in appetite or weight, changes in sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, impaired concentration, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide [7]. PTSD includes exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence leading to persistent symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, hyperarousal, and/or altered reactivity [7]. Anxiety disorders, for example Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), include a state of persistent and excessive anxiety or worry that is difficult to control, associated with physical symptoms (e.g., restlessness, fatigue, muscle tension, and insomnia) and changes in cognition and mood (e.g., impaired concentration and irritability) that cause significant distress or dysfunction [7].

While economic recession may not fit the common description of a disaster that is natural, such as earthquakes, forest fires, or floods, or human-made, such as war, terrorism, or train derailment, it certainly shares many of the consequences of such disasters, including financial loss, resource loss, housing issues or displacement, and stress [4]. Therefore, in this scoping review, we seek to identify and summarize the current evidence of the impact of economic recessions on the rates and characteristics of people who experience depression, anxiety, trauma-related disorders, as well as mental health outcomes related to these disorders (self-harm, suicidal ideation (SI), and suicide), and proxy measurements of this spectrum of depressive, anxious, or trauma-related symptoms and disorders, such as psychotropic drug use and the use of community or hospital-based mental health services, in developed nations. The intent is to explore the breadth of literature available and collate the evidence to further inform policy planning for prevention and protection of population mental health. In this study, we ask how recent economic recessions have impacted the mental health and mortality of the general population in democratic, free-market, first-world nations to increase awareness of at-risk populations during this current era of the global pandemic and recessions and inform efforts to improve surveillance and detection of these mental disorders and illness outcomes during current global recessions.

2. Materials and Methods

We performed a comprehensive search of PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science: Core Collection, National Library of Medicine PubMed, PubMed Central, and Google Scholar between 28 November and 28 December 2020 to identify relevant articles [8]. These sources of evidence were selected based on Bramer et al.’s 2017 study on optimal search strategies for comprehensive and efficient coverage of available literature when conducting systematic reviews [8]. The following search terms were used: “economic recession” AND ((“depressive disorder” OR “depression” OR “major depressive disorder” OR “major depressive episode” OR MDD) OR (“generalized anxiety disorder” OR GAD OR “anxiety”) OR (“post-traumatic stress disorder” OR “ptsd” OR “post traumatic stress disorder”) OR “mental health” OR “mental illness”).

All citations were imported into Proquest by the Refworks citation manager, which was used to sort and store article references. Abstracts were reviewed for each article and the reference list of excluded articles were reviewed for additional relevant literature. Inclusion criteria for articles were quantitative studies of all ages conducted in Organisation for Economic Coordination and Development (OECD) countries assessing mental disorders (excluding those exclusively assessing substance use) during periods of economic recession. Articles were limited to publication dates from 1 January 2008 up to the date that the search was completed (28 November–28 December 2020) to capture the most recent data, including that from the last major global economic recession in 2008.

Exclusion criteria included articles not relevant to the research question, including those using non-specific measures of mental distress or stress, or that were treatment or solution focused. Further excluded were articles that were opinion, editorial, commentary, or non-peer reviewed pieces, that used qualitative methodologies, were conducted in non-OECD countries, published pre-2008, or not available in English or online as these do not address the research question or would not be interpretable by the reviewers.

The authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of all studies identified through the search (primary screening). This was followed by secondary screening during which the full text of all studies that met the inclusion criteria in the primary screening were read and their eligibility to be included in the final review assessed.

Included articles were sorted by a hierarchy of evidence and publication date before study information and results were then collated and summarized by the primary author in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet using study population, design, main outcomes measured, and significant findings related to the research question. These data points and methods were selected to most efficiently summarize the diverse foci and large volume of results included within these search parameters.

No assumptions or simplifications for data variables of search results collated were identified. A critical appraisal of the literature and sources of evidence were not completed during this review, as the aim of a scoping review is to explore the breadth of information available, rather than to assess the relative strength of findings or recommendations.

3. Results

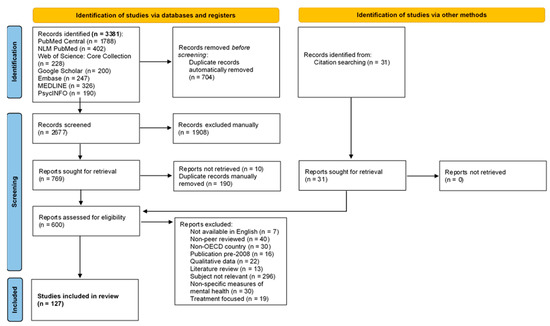

Using the above search parameters, a total of 3381 articles were initially included and imported into Proquest by Refworks citation manager. A total of 31 novel articles were identified by reference list review and imported into the citation manager for a total of 3412 articles reviewed by abstract. See Figure 1 for full details of the literature search [9], a supplementary literature search flowchart may also be found in the Supplementary Figure S1: Literature search flowchart. After the final body of 610 articles were screened for exclusion by two researchers, 127 articles were included in this systematic review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA literature search summary [9].

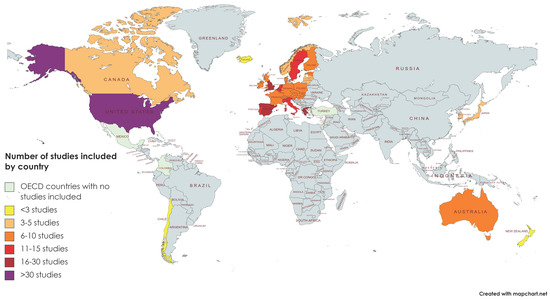

Summary tables of these articles can be found by study topic in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. An extended summary of included articles, can be found in Supplementary Table S1. A breakdown of study geography can be seen in Figure 2. Note that some studies include more than one geographical area and are counted in multiple categories.

Table 1.

Summary of included articles on depression only (N = 30).

Table 2.

Summary of included articles on depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (N = 36).

Table 3.

Summary of included articles on suicidal ideation and self-harm (N = 15).

Table 4.

Summary of included articles on suicide (N = 46).

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of included studies.

Of the 127 articles included, there were 11 (9%) prospective cohort studies, 3 retrospective cohort studies, 1 case-control study, 84 (66%) time-trend analyses, and 28 (22%) cross-sectional analyses.

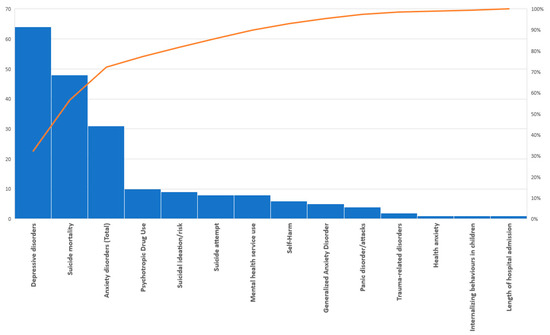

As shown in the pareto analysis (Figure 3), depressive disorders, suicide mortality, and anxiety disorders were the by far the most reported outcomes, accounting for about 70% of the articles included. More specifically, 65 (50%) studies included outcomes on depressive symptoms, 48 (38%) on suicide mortality, and 21 (17%) on anxiety disorders (five on Generalized Anxiety Disorder, four on panic attacks, and one on health anxiety). There were nine on suicidal ideation/suicide risk, eight on suicide attempts, six on self-harm, and two studies that assessed trauma-related disorders. Please note that multiple studies included a combination of these subjects, therefore are counted in more than one of the above outcome categories.

Figure 3.

Pareto chart showing the distribution of included papers by outcomes studied.

Most studies relied on scales or survey data based on self-reported symptoms or clinician diagnosis of symptoms or the disorder. In addition, there were ten articles that assessed rates of psychotropic medication use as a proxy for mental disorders, eight that analyzed mental health service use (community or hospital), one that assessed length of hospital admissions, and one that assessed internalizing behaviours in children.

Populations studied included all adults in 72 articles, working age adults in 36 articles, 9 studies of older adults (definitions ranged from adults >50 to >75 years old), 5 of children and adolescents, 2 that explicitly studied young adults, and 3 on middle-aged adults exclusively.

4. Discussion

Our study found that there has been considerable research on symptoms of depression, anxiety, and suicide mortality associated with periods of economic recession published in English from OECD nations since 2008. Unfortunately, studies on trauma-related disorders, such as PTSD, and in special populations, including children, adolescents, and older adults, were all found to be quite limited. In addition, there has been a considerable body of research in this area representing the European continent, particularly the Mediterranean region and the United Kingdom, as well as the United States of America. Research studies completed in other OECD continental and country blocks were quite limited, as in the Asian and Commonwealth nations, and completely absent in the case of Central and South American OECD nations. No African countries are currently included among the OECD Member Nations.

4.1. Depression

Following the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), an increase in the prevalence of depressive symptoms and disorders was seen across most of the developed world. A pervasive increase in mental health care utilization for depressive symptoms was seen during or following periods of economic recession [10,11,12,13]. Among outpatients, physician visits for mental health care increased among women, those with increased age, family income, health care access/coverage, and education levels in the United States of America (USA); however, visits decreased overall during the recession for both men (25%) and women (7–8%) of all ethnic backgrounds [14,15]. Psychotropic drug use increased post-recession among USA women, USA adults in the Northeast region, USA plant workers, Italian and Spanish adults, and new mental health outpatients in Canada [14,16,17,18,19,20].

Twenty-two studies reviewed the association between unemployment and depression—twenty-one of these studies found a positive relationship between these two factors. Correlation coefficients between unemployment and depressive symptoms/disorders ranged from 0.139–0.68 in two European studies [21,22]. Countries with a higher unemployment rate post-2008 GFC compared to pre-GFC had increased likelihood and severity of depressive symptoms [23,24,25]. Furthermore, the probability of chronic mental illness was found to increase with national unemployment rates during the GFC [26].

Individual-level unemployment was found to increase depressive symptom scores by 0.6–2 points or 3.18–7.33% on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [25,27,28,29]. Job loss during the 2008 GFC was found to increase the odds of having an incident mood disorder 1.65–2.02 times in Greece and the Netherlands, 16.6% in six European countries, or 22.5% in the USA, and in particular, job loss secondary to firm closure had an increase in depressive symptoms of 28.2% in the USA and 7.5% in Europe on the CES-D [28,30,31,32,33]. Similarly, individual level employment was found to decrease depressive symptoms across European nations and for American men during the GFC [34,35,36].

Men appear to be a particularly vulnerable group with multiple studies finding a more robust relationship between depression and unemployment for men than women [22,23,31,37,38,39,40]. Job insecurity has also been associated with increased odds of depression/depressive symptoms 1.3–1.86 times in Europe, the United Kingdom (UK), the USA, or a 33.5% increase in depressive symptoms [23,41,42]. Precarious employment was correlated with higher depressive symptoms scores on the CES-D across 21 European countries (correlation coefficient = 0.077), and a sudden decrease in workload was found to increase the probability of depressive symptoms by 8.6% [34,43,44].

Reduction in income has been associated with increases in depressive symptoms in European, South Korean, and American studies [21,27,31,32,35,45,46,47]. Reduced individual or household income has been associated with 1.77 times increase in odds of an incident mental disorder and 1.74–2.24 times or an 11.7% increase in odds of depressive symptoms/disorder [31,32,35]. Similarly, economic distress and financial strain have been found to increase depressive symptoms by nine out of ten studies assessing these measures [27,30,41,42,48,49,50,51,52]. Reporting economic distress was associated with a 1.5-point increase on the CES-D and a 1.16–1.33 times increased odds ratio of MDD [27,30,42,48,52]. Positive social support was found to be protective against the negative effects financial stress on depression, whereas interpersonal trust was only protective against MDD (5% decreased odds) for those who had low economic distress [50,51].

Housing insecurity was a significant mediating factor in depressive symptoms associated with the 2008 GFC as assessed by seven studies [18,42,53,54,55,56,57]. They found 1.2–5.8 times higher odds of MDD associated with foreclosures, 2.11 times higher odds of depressive disorders associated with mortgage payment difficulties, and 3.7 times higher odds of MDD for those behind on their rent [42,54,55,57].

Overall, life satisfaction, perceived health, eudaimonic well-being, individual optimism, social optimism, close relationships, positive social supports, becoming married, maintaining employment, and having a higher level of education were generally found to be protective against depressive symptoms during the 2008 recession [36,45,49,58].

For people with depression at baseline, preceding the 2008 GFC, they were found to have increased risk during the recession of job loss, becoming a caregiver, or having major illness personally or in a family member [52,59]. There were also 2.2 times increased odds of financial hardship during the recession associated with a 12-month history of any mental disorder that was not significantly related to change in employment, social status, or debt levels [60].

4.2. Anxiety

Overall levels of anxiety were found to be stable or in decline during periods of economic recession among USA and Canadian adults during the 2008 GFC and the 2015 oil recession [18,36,61]. However, among workers in particular, anxiety appears to increase during recessionary periods. In the post-recession period, an 11% increase in anxiolytic prescription was seen among USA plant workers, 7.3% increase sedative prescriptions for Portuguese men, and among workers in Spain, 69.8% of long-term sickness absence was due to anxiety disorders [16,62,63].

Studies found that during times of economic recession, both job insecurity and unemployment were associated with increased anxiety [16,32,63,64,65,66,67]. Income reduction and financial distress were not found to be consistently related to anxiety. While in the Netherlands, no association was found with incident anxiety with decreased household income and onset or recurrence of anxiety disorders across income categories during the recession, in the USA, financial strain and anxiety symptoms were found to be correlated (coefficient = 0.062), as well as in Portugal, Greece, and Spain [31,45,46,49,50,68].

In two studies on GAD, an increased odds ratio for diagnosis was seen in the USA after the 2008 GFC, associated with individuals who experienced financial impacts (odds ratio (OR) 1.3) or foreclosure (OR 1.9), as well as for people with less than college level education (OR 1.8) [42,55]. A one standard deviation increase in financial advantage conferred a 1.3 times increased risk of GAD with each negative housing impact experienced [42].

Three studies assessing symptoms of panic attacks or panic disorder were completed in the USA following the 2008 GFC [42,43,57]. They found increased odds of panic symptoms associated with experiencing a negative financial, job-related, or housing impact (OR 1.2), housing instability (OR 2.5), being behind on the mortgage or foreclosure (OR 3.7), and foreclosure in the past three years (OR 3.5) [42,57]. People who perceived job insecurity were 21.2% more likely to experience anxiety attacks compared to the job secure, and perceived insecurity plus unemployment increased risk beyond perceived insecurity alone [43].

During previous economic recessions, becoming married, having increased occupational prestige, and a higher level of education were found to be protective against anxiety disorders [45,49], whereas interpersonal and institutional trust were not correlated significantly with GAD in whole population samples, or samples of Greek adults in 2011 with low or high levels of financial strain [45,49,51]. Negative social support was correlated with increased anxiety symptoms and positive social support limited the effects of financial stress on anxiety levels [49,50].

4.3. Trauma-Related Disorders

Only two studies that addressed trauma-related disorders met the inclusion criteria. The first is a 2012 study of adults from Detroit, USA that found that people with a history of PTSD were at 6.2 times greater odds of foreclosure during the 2008–2010 GFC [55]. The second is a 2018 time-trend analysis of new patients assessed at mental health clinics in Fort McMurray, Canada, during the oil recession of 2015, which found that the number of new patients with trauma-related diagnoses during the recession compared to pre-recession decreased to 8.2% from 14.2% [18].

4.4. Self-Harm

The five articles included that studied self-harm in adults related to economic recessions all found increased rates of self-harm during or following periods of recession [18,69,70,71,72]. Characteristics associated with higher rates of self-harm included unemployment or job insecurity, financial stressors, and housing insecurity [69,71]. In Ireland, episodes of self-harm among males 31% and 22% among females were beyond the expected rates if pre-recession trends had continued. This resulted in 5029 excess hospital presentations for the treatment of self-harm in men and 3833 for women in the five-year period following the 2008 GFC [72]. In community mental health clinics in Fort McMurray, Canada, new patients with a history of self-harm increased from pre-recession rates of 13.6% of new patients to 16.6% following the 2015 oil recession [18].

4.5. Suicidal Ideation or Attempt

Of 12 studies on SI and attempts related to periods of economic recessions, two did not find a significant change in SI or attempt rates during/post-recession compared to pre-recession. Income inequality and personal economic distress has been associated with an increased risk of SI and attempts in South Korea and Greece [30,47,52]. Studies in Europe found that in the post-recession period people at higher risk of SI and attempt were unemployed, had financial hardship, low interpersonal trust, were married (53 times greater risk than unmarried), perceived a negative impact of the GFC, and had a history of suicide attempt (14.41 times risk) or MDD (97 times greater risk) [27,52,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. The median age of people who attempt suicide increased following the GFC to middle-aged adults, particularly those approaching retirement [74,75,80].

4.6. Suicide

Across 48 studies assessing suicide mortality rates (SMR), nearly all studies found an increase in suicide rates during and following period of recession. A total of three studies in Spain, Italy, and Greece found no significant increase in SMR at a population level [81,82,83]. In a study of SMRs in the USA between 1928 and 2007, rates were found to consistently increase during recessions and decrease during expansions [84]. In some studies, a possible six month to two-year lag in increasing SMRs following the trough in economic activity has been noted [85,86,87].

In Japan, Europe, and the Americas, male SMRs were seen to increase disproportionate to female SMRs in Spain, the Netherlands, Ireland, Eastern Europe, Italy, and across a grouping of 27 European countries [72,80,88,89,90,91,92]. Overall, the 2009 male SMR across 55 countries—27 in Europe and 18 in the Americas—was increased by 3.3% (or 5124 excess suicides) [89]. The SMR for working-aged men (25–64 years) increased by 4.2–12% in European studies, while no significant change was seen for women [89,90]. Across 18 American countries, male SMRs rose 6.4% or 3175 excess suicides following the 2008 GFC, compared to a 2.3% rise among females in the Americas [89]. Other studies in the USA found that the 2008 GFC explained 30% of the change in short- and long-term SMRs observed up to 2016 [86,92].

During periods of crisis, certain characteristics were observed among people who completed suicide, with high levels of neuroticism increasing risk of suicide 2.45 times and increased levels of interpersonal trust being protective against population level suicide [93,94]. Among men, the level of education had an inverse relationship with SMRs, while no clear relationship was observed for women [92]. By age group, five studies found that people (particularly men) of working age, approaching retirement were at higher risk than other age groups [80,82,95,96,97]. Relationship status was inconsistently associated with an increased risk of suicide during a recession [82,95,97]. While mental illness remains one of the most significant risk factors for suicide during times of recession (28% to 61%), multiple studies reported no change, or a decrease in comorbid mental health diagnoses among people who died by suicide in recession times [80,95,97,98,99].

Twenty-three studies assessed SMRs in relation to job security, financial strain, and unemployment. Of these studies, five found no population level association between unemployment levels and SMRs in the USA, Spain, and Italy [82,100,101,102,103]. Suicide rates were found to increase with each 1% increase in male unemployment rates by 0.94–1.6% among men [89,94,104]. The effect of unemployment on SMR was greatest in European countries with the weakest unemployment protection, and across 55 developed nations, countries with a lower pre-crisis unemployment rate (<6.2%) showed a stronger correlation with male suicide rates [89,91]. In addition, each increase in $10 spent by governments on labour market programmes decreased the effect of a 1% increase in male unemployment on SMRs by 0.026% [91]. These findings were supported by national level studies in Australia, Belgium, England, Greece, Hungary, Spain, Sweden, and the USA [93,95,97,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115].

People employed in jobs with low occupational prestige were more likely to commit suicide than high prestige jobs, including managers and supervisors [96,116,117]. Gross domestic product (GDP), markers of economic output (ICEI), and other measures of economic activity have been found to vary counter-cyclically with suicide rates in South Korea, Spain, the USA, Greece, and Europe [83,86,102,108,117,118,119,120].

Five studies reviewed the association between SMR and housing insecurity. Four studies in the USA following the 2008 GFC found a positive association between foreclosure rates and eviction [98,104,121,122]. A 1% increase in foreclosure rate was found to add 1.2 additional suicide deaths per 100,000 across the USA, or a 0.10 suicide rate/100,000 associated with a 1% increase in state-level foreclosure rate [121,122]. However, these rates were most significant for white men, and for those nearing retirement (ages 46–64) [104,121,122]. Real-estate owned foreclosure rate was found to be a stronger predictor than the total foreclosure rate, and 79% of suicides related to foreclosure occurred prior to the actual loss of housing with 37% within two weeks of a crisis related to eviction/foreclosure [98]. Eviction was found to increase odds of suicide 5.94 times among Swedish adults following the 2008 GFC [123].

4.7. Special Populations: Children and Adolescents

In six studies looking at the impact of economic recession on depression children and adolescents, there was evidence of correlation between early socioeconomic adversity and depressive symptoms seen in the UK, USA, Finland, and Sweden [124,125,126,127,128,129]. These changes are at least in part attributable to parental unemployment, household income, parental education level, parenting style, youth unemployment, and a perceived external locus of control in adolescence [124,126,127,128,129].

Two studies addressed anxiety related to recessions in this population, finding that youth exposed to unemployment had an increased odds ratio of anxiety in middle age and that among young adults in Portugal post-recession there was an increase in the use of prescription psychotropic drugs [62,125]. No studies were identified on trauma-related disorders among children and adolescents related to economic recession.

With regards to suicidality, one study of the pediatric population in Denmark found no effect of the GFC [130], while a USA study found that statewide job loss of 1% was related to a 2% increase in SI and a 2.2% increase in suicide plans among adolescent females and a 2.3% increase in SI, a 3.1% increase in suicide plans, and a 2% increase in suicide attempts was seen among non-Hispanic black adolescents [131]. No association was seen for adolescent males, non-Hispanic whites, or Hispanics [131]. A study focused on youth (ages 15–24) from high-income countries found that those in countries with high levels of income inequality and GDP in 2008 saw rising suicide rates among this population [132].

4.8. Special Populations: Older Adults

In eight studies of the impact of economic recessions on depressive symptoms in older adults, results were varied based on factors unique to this population. A study in the USA found that older adults had an increase in MDD diagnosis greater than the general population between 2005 and 2015, and 35.3% of respondents at a health centre in Greece reported that the economic crisis had provoked depressive symptoms [45,128]. For USA adults over 50 years, new food insecurity during the 2008 GFC was associated with 1.7 times odds of MDD compared to those who were food insecure at baseline [133]. For older adults with newly co-residential adult children during the 2008 recession in the USA, CES-D scores were seen to increase on average 0.179 points. If co-residential adult children were unemployed (vs. employed), the CES-D score increased an average of 0.522 points [134]. In addition, education, chronic disease presence, annual income, and a reduction in income >20% were not associated with levels of geriatric depression among respondents in Greece [45]. In contrast, two studies of 13 European countries found that retirement was protective against depressive symptoms, particularly for blue-collar workers in regions severely hit by the economic crisis [34,135].

Three studies were included that addressed the impacts of economic recessions on anxiety symptoms in older adults [62,66,136]. A prospective cohort study of older adults in Australia found that the economic slowdown during the GFC correlated with an increase in anxiety symptoms not explained by sociodemographic or economic factors [136]. Overall psychotropic drug use among older adults was not observed to change post-recession, but among female retirees and home makers post-recession in Spain, the odds ratio of sedative use increased 1.23 and 1.30 times, respectively [62,66].

No studies were identified addressing trauma-related disorders or self-harm among older adults related to economic recessions. In one cross-sectional study in Spain after the 2008 GFC, they found that adults aged 65 and older were more likely to report SI in the context of household financial problems than other age ranges surveyed [78].

Three studies were included that specified impacts of economic recession on suicides among older adults. One study found that for adults over age 65 a decrease in the ICEI was protective against suicide, and in another, an inverse relationship was seen between the foreclosure rate and suicides among adults over age 65 [104,118]. However, in contrast, a study in the Netherlands found a sudden increase in SMRs in 2007–2013, with a shift in the peak age group of suicides among men from 30–39 years to 60–69 years after 2008 and among women this shifted from 30–39 to 50–59 years old [80].

4.9. Limitations

The results of this study are limited by the quality and diversity of data available and included in the review. A critical appraisal of included articles was not completed as part of this scoping review. In addition, although the inclusion criteria limited studies to current quantitative evidence since 2008, published in peer-reviewed journals, and conducted in OECD countries, the data included are highly diverse and reflective of a broad spectrum of political and economic climates and policies. Therefore, these data may not be generalizable; caution should be used in interpreting findings on topics included in this study with limited data available, such as trauma-related disorders, and all topics reviewed for pediatric and geriatric populations. This study does identify considerable room for further research in these areas. Furthermore, data included are gathered at a population level and may not be generalizable to any specific individual.

This review seeks to summarize available data quantifying the mental health impacts of economic recessions but does not specifically include evidence-based interventions to manage the same; statements made in this regard are largely speculative in nature. The exclusion of qualitative research limits the ability of this review to comment on explanatory issues around mental health in economic recessions.

The basis of each economic recession studied is varied, with many studies based on recessions following an economic crisis in the housing markets or stock markets. Therefore, the specific populations impacted by the current COVID-19 pandemic, as well as rates of mental illness and suicide, may vary and risk levels among sub-populations may diverge from those seen in previous recessions.

Potential biases in this study in the search strategy include the possibility of failing to include research studies that did not address the target mental disorders and economic recessions as their primary outcome and may not have included this in the abstract of the article but did discuss relevant information. In addition, articles citing these subjects but not completing primary research in this area would return as search results utilizing this strategy. These issues were addressed by a review of all excluded articles for relevant citations in their reference lists prior. The limitation of studies to English language only significantly biases this review towards research completed in anglophone nations within the OECD and may not be representative of this entire group. In addition, articles not accessible online or through major databases were not included in this search strategy and results are therefore biased by the inclusion criteria for databases utilized. We attempted to mitigate these concerns by using a combination of both subscription-based and open-access databases and search engines. Finally, there is a risk of reviewer bias inherent in this type of study, which was diminished by utilizing two reviewers in the article review process.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the results of this scoping review suggest that general models for providing mental health support and strategies for suicide prevention may be less effective in reaching those whose mental health is negatively impacted by an economic recession than they are in non-recession times [14,15,80,95,97,98,99]. The populations found by most studies to primarily be effected by depression, self-harm, and suicide secondary to economic recession include men approaching retirement age, people with low education, high levels of unemployment or job insecurity, and low pre-recession socioeconomic status, yet those most likely to access mental health supports were found to be women and highly educated adults [14,15]. Additionally, analyses of the characteristics of people who committed suicide related to economic recession found that they were less likely to access the family physician or mental health supports, or be formally diagnosed with mental illness, prior to suicide compared to non-recession related suicides [80,95,97,98,99]. Therefore, it may be prudent to focus public educational efforts to increase vigilance to identify people in need of support at a community level, among places of employment, unemployment, or income support offices. For healthcare providers, people presenting with complaints of mental health concerns during recession times, particularly those in the higher risk groups outlined above, should be carefully evaluated for SI and safety; and perhaps a lower threshold for treatment may be warranted.

At a governmental level, policy makers should be aware of the potential protective nature of unemployment protections and labour program investment in mitigating the negative impacts of economic recession on population level mental health and suicide mortality [89,91,94]. However, increasing resources during times of recession is inherently challenging, as governments are limited in their ability to invest in new mental health supports by the economic reality of a recession. As such, during recessions, governments typically lay off staff, do not replace retiring staff, or avoid creating new heavily human resource intensive mental health services [137,138]. Therefore, health policy and practice implications should also consider the adoption of low cost, evidence-based interventions such as bibliotherapy, Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, supportive text messaging, and encouragement of community and family level emotional support [138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162]. Research evidence has suggested that support from family and friends is protective during natural disasters and two studies in this review suggest that positive social support provides additional protection against anxiety and depression during times of economic recession [49,50]. Therefore, study of low-cost interventions for mitigation and treatment of mental health concerns during periods of economic recession could be a tremendously beneficial area for future study.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bs11090119/s1, Table S1: Extended summary of included articles, and Figure S1: Literature search flowchart.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.G. and E.E.; data curation, O.G.; formal analysis, O.G. and E.E.; investigation, O.G.; methodology, O.G. and E.E.; project administration, O.G.; supervision, E.E.; validation, O.G. and E.E.; visualization, O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.G.; writing—review and editing, O.G. and E.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Access to subscription-based databases was funded through the University of Alberta Library.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the supervision of Vincent Agyapong, in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Alberta.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- COVID-19 to Plunge Global Economy into Worst Recession since World War II. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/06/08/covid-19-to-plunge-global-economy-into-worst-recession-since-world-war-ii (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Baffes, J.; Dieppe, A.M.; Guenette, J.D.; Kabundi, A.N.; Kasyanenko, S.; Kilic Celik, S.; Kindberg-Hanlon, G.; Kirby, P.A.; Maliszewska, M.; Matsuoka, H.; et al. Global Economic Prospects: June 2020 (English); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–238. [Google Scholar]

- Baffes, J.; Guenette, J.D.; Ha, J.; Inami, O.; Kabundi, A.N.; Kasyanenko, S.; Kilic Celik, S.; Kindberg-Hanlon, G.; Kirby, P.A.; Nagle, P.S.O.; et al. Global Economic Prospects 2021 (English); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 1–198. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health and Disasters; Neria, Y., Galea, S., Norris, F.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F.H.; Friedman, M.J.; Watson, P.J. 60,000 Disaster Victims Speak: Part II. Summary and Implications of the Disaster Mental Health Research. Psychiatry 2002, 65, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Friedman, M.J.; Watson, P.J.; Byrne, C.M.; Diaz, E.; Kaniasty, K. 60,000 Disaster Victims Speak: Part I. An Empirical Review of the Empirical Literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 2002, 65, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. Available online: http://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71 (accessed on 21 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fattore, G. The impact of the great economic crisis on mental health care in Italy. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel-Herrero, A.; Gomez-Beneyto, M. The impact of the 2008 economic crisis on the increasing number of young psychiatric inpatients. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2017, 12, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekiso, T.B.; Heron, E.A.; Masood, B.; Murphy, M.; McLoughlin, D.M.; Kennedy, N. Mauling of the “Celtic Tiger”: Clinical characteristics and outcome of first-episode depression secondary to the economic recession in Ireland. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.F.S.; Nunes, C. Inpatient Profile of Patients with Major Depression in Portuguese National Health System Hospitals, in 2008 and 2013: Variation in a Time of Economic Crisis. Community Ment. Health J. 2018, 54, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dagher, R. Gender and Race/Ethnicity Differences in Mental Health Care Use before and during the Great Recession. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2016, 43, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, M.; Teitler, J. Darker days? Recent trends in depression disparities among US adults. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrek, S.; Hamad, R.; Cullen, M.R. Psychological well-being during the great recession: Changes in mental health care utilization in an occupational cohort. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, M.A.; Coll-Negre, M.; Coll-de-Tuero, G.; Saez, M. Effects of the Financial Crisis on Psychotropic Drug Consumption in a Cohort from a Semi-Urban Region in Catalonia, Spain. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, A.; Hrabok, M.; Igwe, O.; Omeje, J.; Ogunsina, O.; Ambrosano, L.; Corbett, S.; Juhas, M.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Impact of oil recession on community mental health service utilization in an oil sands mining region in Canada. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, W.D.; Lastrapes, W.D. A prescription for unemployment? Recessions and the demand for mental health drugs. Health Econ. 2014, 23, 1301–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittadini, G.; Beghi, M.; Mezzanzanica, M.; Ronzoni, G.; Cornaggia, C.M. Use of psychotropic drugs in Lombardy in time of economic crisis (2007–2011): A population-based study of adult employees. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibling, N.; Beckfield, J.; Huijts, T.; Schmidt-Catran, A.; Thomson, K.H.; Wendt, C. Depressed during the depression: Has the economic crisis affected mental health inequalities in Europe? Findings from the European Social Survey (2014) special module on the determinants of health. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, T.; Stuart, B.; Newell, C.; Geraghty, A.W.; Moore, M. Changes in rates of recorded depression in English primary care 2003–2013: Time trend analyses of effects of the economic recession, and the GP contract quality outcomes framework (QOF). J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 180, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, V.; Van de Velde, S.; Bracke, P. The mental health consequences of the economic crisis in Europe among the employed, the unemployed, and the non-employed. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 54, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, B.; Kinderman, P.; Whitehead, M. Trends in mental health inequalities in England during a period of recession, austerity and welfare reform 2004 to 2013. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia Granados, J.A.; Christine, P.J.; Ionides, E.L.; Carnethon, M.R.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Kiefe, C.I.; Schreiner, P.J. Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Depression, and Alcohol Consumption During Joblessness and during Recessions among Young Adults in CARDIA. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 2339–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.C.; Cheng, T.C. Race, unemployment rate, and chronic mental illness: A 15-year trend analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, S.L.; Elfassy, T.; Bailey, Z.; Florez, H.; Feaster, D.J.; Calonico, S.; Sidney, S.; Kiefe, C.I.; Al Hazzouri, A.Z. Association of negative financial shocks during the Great Recession with depressive symptoms and substance use in the USA: The CARDIA study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riumallo-Herl, C.; Basu, S.; Stuckler, D.; Courtin, E.; Avendano, M. Job loss, wealth and depression during the Great Recession in the USA and Europe. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drydakis, N. The effect of unemployment on self-reported health and mental health in Greece from 2008 to 2013: A longitudinal study before and during the financial crisis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 128, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madianos, M.; Economou, M.; Alexiou, T.; Stefanis, C. Depression and economic hardship across Greece in 2008 and 2009: Two cross-sectional surveys nationwide. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 46, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbaglia, M.G.; Have, M.T.; Dorsselaer, S.; Alonso, J.; de Graaf, R. Negative socioeconomic changes and mental disorders: A longitudinal study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witteveen, D.; Velthorst, E. Economic hardship and mental health complaints during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27277–27284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, J.; Stevens, A.H. Short-run effects of job loss on health conditions, health insurance, and health care utilization. J. Health Econ. 2015, 43, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelrad, H.; Sabbath, E.L.; Hawkins, S.S. The impact of the 2008 recession on the health of older workers: Data from 13 European countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, M.H.; Andreeva, E.; Theorell, T.; Goldberg, M.; Westerlund, H.; Leineweber, C.; Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Imbernon, E.; Bonnaud, S. Organizational downsizing and depressive symptoms in the European recession: The experience of workers in France, Hungary, Sweden and the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagher, R.K.; Chen, J.; Thomas, S.B. Gender Differences in Mental Health Outcomes before, during, and after the Great Recession. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economou, M.; Angelopoulos, E.; Peppou, L.E.; Souliotis, K.; Stefanis, C. Major depression amid financial crisis in Greece: Will unemployment narrow existing gender differences in the prevalence of the disorder in Greece? Psychiatry Res. 2016, 242, 260–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.P.; Sousa-Uva, M.; Fonseca, R.; Marques, S.; Pina, N.; Matias-Dias, C. Depression and unemployment incidence rate evolution in Portugal, 1995–2013: General Practitioner Sentinel Network data. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.E.; Lee, J.; Sohn, J.H.; Seong, S.J.; Cho, M.J. Ten-year trends in the prevalence and correlates of major depressive disorder in Korean near-elderly adults: A comparison of repeated nationwide cross-sectional studies from 2001 and 2011. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelekasis, P.; Kampoli, K.; Ntavatzikos, A.; Charoni, A.; Tsionou, C.; Koumarianou, A. Depressive symptoms during adverse economic and political circumstances: A comparative study on Greek female breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy treatment. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, H.; Bebbington, P.; Brugha, T.; Jenkins, R.; McManus, S.; Stansfeld, S. Job insecurity, socio-economic circumstances and depression. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, M.K.; Krueger, R.F. The great recession and mental health in the United States. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgard, S.A.; Kalousova, L.; Seefeldt, K.S. Perceived job insecurity and health: The Michigan Recession and Recovery Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 54, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrek, S.; Cullen, M.R. Health consequences of the ‘Great Recession’ on the employed: Evidence from an industrial cohort in aluminum manufacturing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 92, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrou, G.; Paikousis, L.; Jelastopulu, E.; Charalambous, G. Mental Health in Cypriot Citizens of the Rural Health Centre Kofinou. Healthcare 2016, 4, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Mateu, F.; Tormo, M.J.; Salmerón, D.; Vilagut, G.; Navarro, C.; Ruíz-Merino, G.; Escámez, T.; Júdez, J.; Martínez, S.; Kessler, R.C.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Disorders in the South-East of Spain, One of the European Regions Most Affected by the Economic Crisis: The Cross-Sectional PEGASUS-Murcia Project. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Knapp, M.; Mcguire, A. Income-related inequalities in the prevalence of depression and suicidal behaviour: A 10-year trend following economic crisis. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economou, M.; Madianos, M.; Peppou, L.E.; Patelakis, A.; Stefanis, C.N. Major depression in the era of economic crisis: A replication of a cross-sectional study across Greece. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 145, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.R. Financial Strain and Mental Health Among Older Adults During the Great Recession. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viseu, J.; Leal, R.; de Jesus, S.N.; Pinto, P.; Pechorro, P.; Greenglass, E. Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: Moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 268, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economou, M.; Madianos, M.; Peppou, L.E.; Souliotis, K.; Patelakis, A.; Stefanis, C. Cognitive social capital and mental illness during economic crisis: A nationwide population-based study in Greece. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 100, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, M.; Peppou, L.E.; Souliotis, K.; Konstantakopoulos, G.; Papaslanis, T.; Kontoangelos, K.; Nikolaidi, S.; Stefanis, N. An association of economic hardship with depression and suicidality in times of recession in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 279, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagney, K.A.; Browning, C.R.; Iveniuk, J.; English, N. The Onset of Depression during the Great Recession: Foreclosure and Older Adult Mental Health. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gili, M.; Roca, M.; Basu, S.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: Evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Nandi, A.; Keyes, K.M.; Uddin, M.; Aiello, A.E.; Galea, S.; Koenen, K.C. Home foreclosure and risk of psychiatric morbidity during the recent financial crisis. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Solano, M.; Bolívar-Muñoz, J.; Mateo-Rodríguez, I.; Robles-Ortega, H.; Fernández-Santaella, M.D.C.; Mata-Martín, J.L.; Vila-Castellar, J.; Daponte-Codina, A. Associations between Home Foreclosure and Health Outcomes in a Spanish City. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgard, S.A.; Seefeldt, K.S.; Zelner, S. Housing instability and health: Findings from the Michigan Recession and Recovery Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2215–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, C.; Castellanos, T.; Abrams, M.; Vazquez, C. The impact of economic recessions on depression and individual and social well-being: The case of Spain (2006–2013). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruchno, R.; Heid, A.R.; Wilson-Genderson, M. The Great Recession, Life Events, and Mental Health of Older Adults. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2017, 84, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, A.; Frasquilho, D.; Azeredo-Lopes, S.; Silva, M.; Cardoso, G.; Caldas-de-Almeida, J.M. Changes in socioeconomic position among individuals with mental disorders during the economic recession in Portugal: A follow-up of the National Mental Health Survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 28, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Smailes, E.; Sareen, J.; Fick, G.H.; Schmitz, N.; Patten, S.B. The prevalence of mental disorders in the working population over the period of global economic crisis. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Antunes, A.; Azeredo-Lopes, S.; Cardoso, G.; Xavier, M.; Saraceno, B.; Caldas-de-Almeida, J.M. How did the use of psychotropic drugs change during the Great Recession in Portugal? A follow-up to the National Mental Health Survey. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, E.; Jover, L.; Verdaguer, R.; Griera, A.; Segalàs, C.; Alonso, P.; Contreras, F.; Arteman, A.; Menchón, J.M. Factors Associated with Long-Term Sickness Absence Due to Mental Disorders: A Cohort Study of 7.112 Patients during the Spanish Economic Crisis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norberto, M.J.; Rodríguez-Santos, L.; Cáceres, M.C.; Montanero, J. Analysis of Consultation Demand in a Mental Health Centre during the Recent Economic Recession. Psychiatr. Q 2020, 92, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codagnone, C.; Bogliacino, F.; Gómez, C.; Charris, R.; Montealegre, F.; Liva, G.; Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F.; Folkvord, F.; Veltri, G.A. Assessing concerns for the economic consequence of the COVID-19 response and mental health problems associated with economic vulnerability and negative economic shock in Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, E.; Cabrera-León, A.; Renart, G.; Saurina, C.; Serra Saurina, L.; Daponte, A.; Saez, M. Did psychotropic drug consumption increase during the 2008 financial crisis? A cross-sectional population-based study in Spain. BMJ Open 2018, 9, e021440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Taylor, A.W.; Goldney, R.; Winefield, H.; Gill, T.K.; Tuckerman, J.; Wittert, G. The use of a surveillance system to measure changes in mental health in Australian adults during the global financial crisis. Int. J. Public Health 2011, 56, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra-Kersten, S.M.; Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, K.E.; van der Wouden, J.C.; Penninx, B.W.; van Marwijk, H.W. Associations of financial strain and income with depressive and anxiety disorders. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, C.; Hawton, K.; Geulayov, G.; Waters, K.; Ness, J.; Rehman, M.; Townsend, E.; Appleby, L.; Kapur, N. Self-harm in midlife: Analysis using data from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 215, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geulayov, G.; Kapur, N.; Turnbull, P.; Clements, C.; Waters, K.; Ness, J.; Townsend, E.; Hawton, K. Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England, 2000–2012: Findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Bergen, H.; Geulayov, G.; Waters, K.; Ness, J.; Cooper, J.; Kapur, N. Impact of the recent recession on self-harm: Longitudinal ecological and patient-level investigation from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, P.; Griffin, E.; Arensman, E.; Fitzgerald, A.P.; Perry, I.J. Impact of the economic recession and subsequent austerity on suicide and self-harm in Ireland: An interrupted time series analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, C.; Efstathiou, V.; Michopoulos, I.; Ferentinos, P.; Korkoliakou, P.; Gkerekou, M.; Bouras, G.; Papadopoulou, A.; Papageorgiou, C.; Douzenis, A. A case-control study of hopelessness and suicidal behavior in the city of Athens, Greece. The role of the financial crisis. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, M.; Madianos, M.; Peppou, L.E.; Theleritis, C.; Patelakis, A.; Stefanis, C. Suicidal ideation and reported suicide attempts in Greece during the economic crisis. World Psychiatry 2013, 12, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakopoulos, G.; Pikouli, K.; Ploumpidis, D.; Bougonikolou, E.; Kouyanou, K.; Nystazaki, M.; Economou, M. The impact of unemployment on mental health examined in a community mental health unit during the recent financial crisis in Greece. Psychiatriki 2019, 30, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntountoulaki, E.; Paika, V.; Papaioannou, D.; Guthrie, E.; Kotsis, K.; Fountoulakis, K.N.; Carvalho, A.F.; Hyphantis, T.; ASSERT-DEP Study Group members. The relationship of the perceived impact of the current Greek recession with increased suicide risk is moderated by mental illness in patients with long-term conditions. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017, 96, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Doña, J.A.; San Sebastián, M.; Escolar-Pujolar, A.; Martínez-Faure, J.E.; Gustafsson, P.E. Economic crisis and suicidal behaviour: The role of unemployment, sex and age in Andalusia, Southern Spain. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miret, M.; Caballero, F.F.; Huerta-Ramirez, R.; Moneta, M.V.; Olaya, B.; Chatterji, S.; Haro, J.M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. Factors associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in Spain for different age groups. Prevalence before and after the onset of the economic crisis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 163, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderoost, F.; van der Wielen, S.; van Nunen, K.; Van Hal, G. Employment loss during economic crisis and suicidal thoughts in Belgium: A survey in general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Beurs, D.P.; Hooiveld, M.; Kerkhof, A.J.F.M.; Korevaar, J.C.; Donker, G.A. Trends in suicidal behaviour in Dutch general practice 1983–2013: A retrospective observational study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Perez, I.; Rodriguez-Barranco, M.; Rojas-Garcia, A.; Mendoza-Garcia, O. Economic crisis and suicides in Spain. Socio-demographic and regional variability. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017, 18, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzagora, I.; Mugellini, G.; Amadasi, A.; Travaini, G. Suicide Risk and the Economic Crisis: An Exploratory Analysis of the Case of Milan. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Savopoulos, C.; Siamouli, M.; Zaggelidou, E.; Mageiria, S.; Iacovides, A.; Hatzitolios, A.I. Trends in suicidality amid the economic crisis in Greece. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 263, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Florence, C.S.; Quispe-Agnoli, M.; Ouyang, L.; Crosby, A.E. Impact of Business Cycles on US Suicide Rates, 1928–2007. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, M.; Yip, P.S.F. Assessing the impact of the economic crises in 1997 and 2008 on suicides in Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea using a strata-bootstrap algorithm. J. Appl. Stat. 2020, 47, 666–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrrawal, P.; Waggle, D.; Sandweiss, D.H. Suicides as a response to adverse market sentiment (1980–2016). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.A.; Nugent, C.N. Suicide and the Great Recession of 2007–2009: The role of economic factors in the 50 U.S. States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 116, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.Y.; Reither, E.N.; Masters, R.K. A population-based analysis of increasing rates of suicide mortality in Japan and South Korea, 1985–2010. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Stuckler, D.; Yip, P.; Gunnell, D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: Time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ 2013, 347, f5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompili, M.; Vichi, M.; Innamorati, M.; Lester, D.; Yang, B.; Leo, D.D.; Girardi, P. Suicide in Italy during a time of economic recession: Some recent data related to age and gender based on a nationwide register study. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norström, T.; Grönqvist, H. The Great Recession, unemployment and suicide. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell, C.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; Gotsens, M.; Calvo, M.; Rodríguez-Sanz, M.; Bartoll, X.; Esnaola, S. Socioeconomic inequalities in suicide mortality before and after the economic recession in Spain. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanji, F.; Kakizaki, M.; Sugawara, Y.; Watanabe, I.; Nakaya, N.; Minami, Y.; Fukao, A.; Tsuji, I. Personality and suicide risk: The impact of economic crisis in Japan. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A.; McKee, M.; Gunnell, D.; Chang, S.; Basu, S.; Barr, B.; Stuckler, D. Economic shocks, resilience, and male suicides in the Great Recession: Cross-national analysis of 20 EU countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.; Hunt, I.M.; Rahman, M.S.; Shaw, J.; Appleby, L.; Kapur, N. Recession, recovery and suicide in mental health patients in England: Time trend analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 215, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, E.C.; Kavalidou, K.; Messolora, F. Suicide Mortality Patterns in Greek Work Force before and during the Economic Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coope, C.; Donovan, J.; Wilson, C.; Barnes, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Hollingworth, W.; Kapur, N.; Hawton, K.; Gunnell, D. Characteristics of people dying by suicide after job loss, financial difficulties and other economic stressors during a period of recession (2010–2011): A review of coroners׳ records. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 183, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, K.A.; Gladden, R.M.; Vagi, K.J.; Barnes, J.; Frazier, L. Increase in Suicides Associated with Home Eviction and Foreclosure During the US Housing Crisis: Findings From 16 National Violent Death Reporting System States, 2005–2010. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beautrais, A.L. Farm suicides in New Zealand, 2007–2015: A review of coroners’ records. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2018, 52, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirci, Ş.; Konca, M.; Yetim, B.; İlgün, G. Effect of economic crisis on suicide cases: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Contreras, N.; Rodríguez-Sanz, M.; Novoa, A.; Borrell, C.; Muñiz, J.M.; Gotsens, M. Socioeconomic inequalities in suicide mortality in Barcelona during the economic crisis (2006–2016): A time trend study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Salinas-Perez, J.A.; Rodero-Cosano, M.L.; Salvador-Carulla, L. Methodological barriers to studying the association between the economic crisis and suicide in Spain. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurina, C.; Marzo, M.; Saez, M. Inequalities in suicide mortality rates and the economic recession in the municipalities of Catalonia, Spain. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kerr, W.C.; Kaplan, M.S.; Huguet, N.; Caetano, R.; Giesbrecht, N.; McFarland, B.H. Economic Recession, Alcohol, and Suicide Rates: Comparative Effects of Poverty, Foreclosure, and Job Loss. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurina, C.; Bragulat, B.; Saez, M.; López-Casasnovas, G. A conditional model for estimating the increase in suicides associated with the 2008–2010 economic recession in England. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, B.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Scott-Samuel, A.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Suicides associated with the 2008–10 economic recession in England: Time trend analysis. BMJ 2012, 345, e5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanthomme, K.; Gadeyne, S. Unemployment and cause-specific mortality among the Belgian working-age population: The role of social context and gender. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachiotis, G.; Stuckler, D.; McKee, M.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. What has happened to suicides during the Greek economic crisis? Findings from an ecological study of suicides and their determinants (2003–2012). BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, M.; Vgontzas, A.; Kastanaki, A.; Michalodimitrakis, M.; Kanaki, K.; Koutra, K.; Anastasaki, M.; Simos, P. ‘Suicide rates in Crete, Greece during the economic crisis: The effect of age, gender, unemployment and mental health service provision’. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcy, A.M.; Vågerö, D. Unemployment and Suicide During and After a Deep Recession: A Longitudinal Study of 3.4 Million Swedish Men and Women. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Gonda, X.; Dome, P.; Theodorakis, P.N.; Rihmer, Z. Possible delayed effect of unemployment on suicidal rates: The case of Hungary. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2014, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coope, C.; Gunnell, D.; Hollingworth, W.; Hawton, K.; Kapur, N.; Fearn, V.; Wells, C.; Metcalfe, C. Suicide and the 2008 economic recession: Who is most at risk? Trends in suicide rates in England and Wales 2001–2011. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 117, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, A.; Morrell, S.; LaMontagne, A.D. Economically inactive, unemployed and employed suicides in Australia by age and sex over a 10-year period: What was the impact of the 2007 economic recession? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 1500–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez Bernal, J.A.; Gasparrini, A.; Artundo, C.M.; McKee, M. The effect of the late 2000s financial crisis on suicides in Spain: An interrupted time-series analysis. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempstead, K.A.; Phillips, J.A. Rising Suicide Among Adults Aged 40–64 Years: The Role of Job and Financial Circumstances. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 48, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, A.J.; Niven, H.; LaMontagne, A.D. Occupational class differences in suicide: Evidence of changes over time and during the global financial crisis in Australia. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Sun, J.J.; Choi, J.; Mo-Yeol, K. Suicide Trends over Time by Occupation in Korea and Their Relationship to Economic Downturns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.; Charters, T.J.; Strumpf, E.C.; Galea, S.; Nandi, A. Economic downturns and suicide mortality in the USA, 1980–2010: Observational study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Kawohl, W.; Theodorakis, P.N.; Kerkhof, A.J.; Navickas, A.; Höschl, C.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Sorel, E.; Rancans, E.; Palova, E.; et al. Relationship of suicide rates to economic variables in Europe: 2000–2011. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 205, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, A.; Prescott, M.R.; Cerdá, M.; Vlahov, D.; Tardiff, K.J.; Galea, S. Economic Conditions and Suicide Rates in New York City. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 175, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J.N.; Light, M.T. The harder they fall? Sex and race/ethnic specific suicide rates in the U.S. foreclosure crisis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 180, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J.N.; Light, M.T. The Home Foreclosure Crisis and Rising Suicide Rates, 2005 to 2010. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, Y.; Stenberg, S. Evictions and suicide: A follow-up study of almost 22,000 Swedish households in the wake of the global financial crisis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culpin, I.; Stapinski, L.; Miles, Ö.B.; Araya, R.; Joinson, C. Exposure to socioeconomic adversity in early life and risk of depression at 18 years: The mediating role of locus of control. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 183, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, P.; Hammarström, A.; Janlert, U. Children of boom and recession and the scars to the mental health—A comparative study on the long-term effects of youth unemployment. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.; Waldfogel, J.; Brooks-Gunn, J. The great recession and behavior problems in 9-year-old children. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 1615–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torikka, A.; Kaltiala-Heino, R.; Rimpelä, A.; Marttunen, M.; Luukkaala, T.; Rimpelä, M. Self-reported depression is increasing among socio-economically disadvantaged adolescents–repeated cross-sectional surveys from Finland from 2000 to 2011. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, A.H.; Gbedemah, M.; Martinez, A.M.; Nash, D.; Galea, S.; Goodwin, R.D. Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: Widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarstrom, A.; Virtanen, P. The importance of financial recession for mental health among students: Short-and long-term analyses from an ecosocial perspective. J. Public Health Res. 2019, 8, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steeg, S.; Carr, M.J.; Mok, P.L.H.; Pedersen, C.B.; Antonsen, S.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Kapur, N.; Erlangsen, A.; Nordentoft, M.; Webb, R.T. Temporal trends in incidence of hospital-treated self-harm among adolescents in Denmark: National register-based study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 55, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassman-Pines, A.; Ananat, E.O.; Gibson-Davis, C.M. Effects of Statewide Job Losses on Adolescent Suicide-Related Behaviors. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1964–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanathan, P.; Bould, H.; Winstone, L.; Moran, P.; Gunnell, D. Social media use, economic recession and income inequality in relation to trends in youth suicide in high-income countries: A time trends analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmans, R.S.; Wegryn-Jones, R. Examining associations of food insecurity with major depression among older adults in the wake of the Great Recession. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 258, 113033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, J. Crowded Nests: Parent-Adult Child Co-residence Transitions and Parental Mental Health Following the Great Recession. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2019, 60, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, M.; Meschi, E.; Pasini, G. The Effect on Mental Health of Retiring during the Economic Crisis. Health Econ. 2016, 25, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent-Cox, K.; Butterworth, P.; Anstey, K.J. The global financial crisis and psychological health in a sample of Australian older adults: A longitudinal study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staines, A.; Balanda, K.P.; Barron, S.; Corcoran, Y.; Fahy, L.; Gallagher, L.; Greally, T.; Kilroe, J.; Mohan, C.M.; Matthews, A.; et al. Child Health Care in Ireland. J. Pediatr. 2016, 177S, S87–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, M.; Thornicroft, G. Specialist mental health services in England in 2014: Overview of funding, access and levels of care. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2015, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanner, D.; Urquhart, C. Bibliotherapy for mental health service users Part 1: A systematic review. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2008, 25, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Bert, F.; Martorana, M.; Voglino, G.; Andriolo, V.; Thomas, R.; Gramaglia, C.; Zeppegno, P.; Siliquini, R. The long-term effects of bibliotherapy in depression treatment: Systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 58, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HANDI Project Team; Usher, T. Bibliotherapy for depression. Aust. Fam. Physician 2013, 42, 199–200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, J.; Vallance, D.; McGrath, M. An evaluation of a collaborative bibliotherapy scheme delivered via a library service. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 20, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlbring, P.; Andersson, G.; Cuijpers, P.; Riper, H.; Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018, 47, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G.; Cuijpers, P.; Carlbring, P.; Riper, H.; Hedman, E. Guided Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Luaces, L.; Johns, E.; Keefe, J.R. The Generalizability of Randomized Controlled Trials of Self-Guided Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depressive Symptoms: Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyotaki, E.; Riper, H.; Twisk, J.; Hoogendoorn, A.; Kleiboer, A.; Mira, A.; Mackinnon, A.; Meyer, B.; Botella, C.; Littlewood, E.; et al. Efficacy of Self-guided Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in the Treatment of Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karyotaki, E.; Kemmeren, L.; Riper, H.; Twisk, J.; Hoogendoorn, A.; Kleiboer, A.; Mira, A.; Mackinnon, A.; Meyer, B.; Botella, C.; et al. Is self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) harmful? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 2456–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.K.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Bernhardt, J.M. Mobile text messaging for health: A systematic review of reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]