Sexual Minority Status, Anxiety–Depression, and Academic Outcomes: The Role of Campus Climate Perceptions among Italian Higher Education Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Minority Stress Framework

1.2. Campus Climate and Negative Outcomes in Sexual Minority Students

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Controls

2.2.2. Perceptions of Campus Climate

2.2.3. Anxiety–Depression

2.2.4. Academic Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

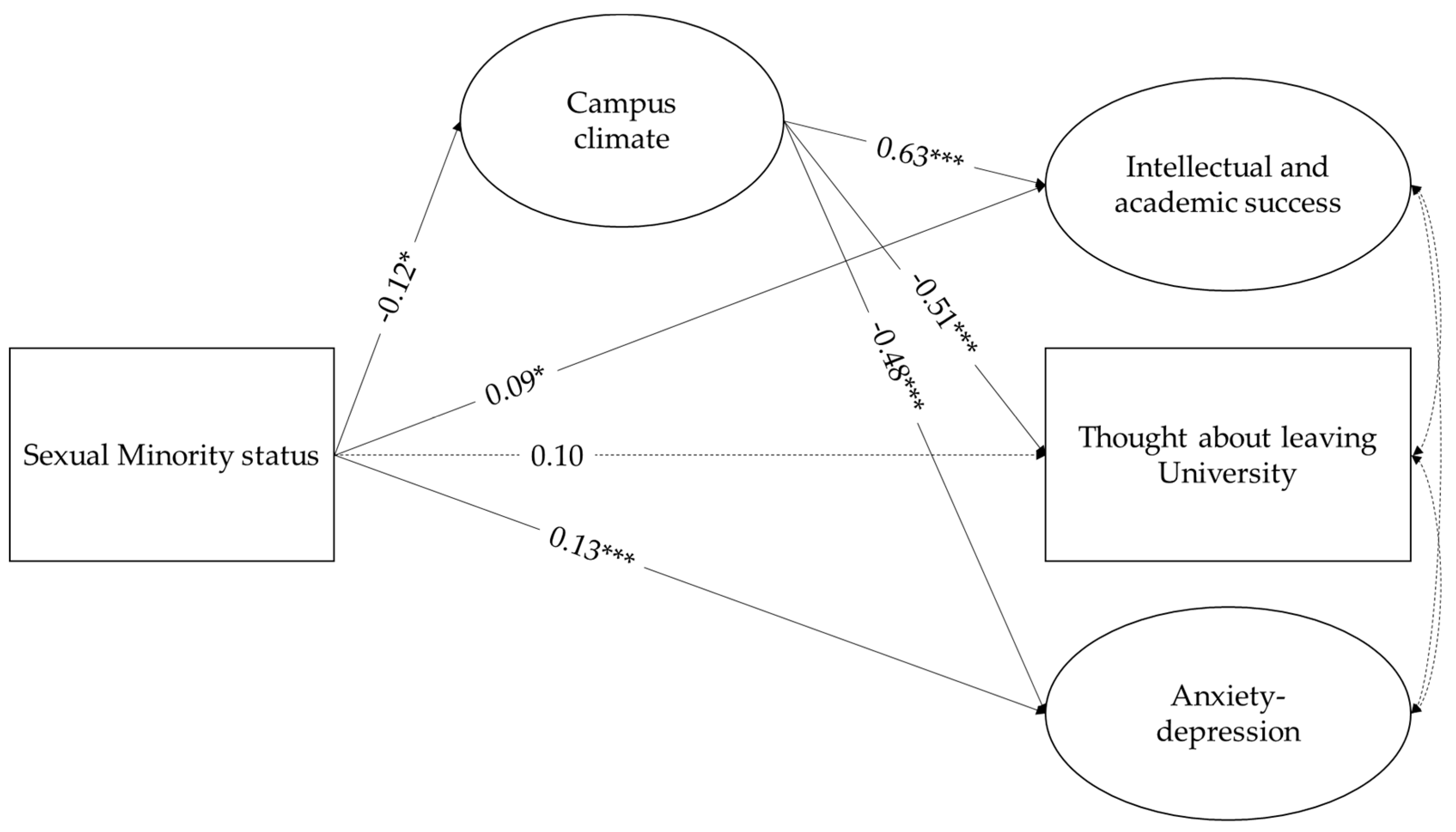

3.2. Sexual Minority Status, Perceptions of Campus Climate and Negative Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mizzi, R.C.; Walton, G. Catchalls and Conundrums: Theorizing “Sexual Minority” in Social, Cultural, and Political Contexts. Philos. Inq. Educ. 2014, 22, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, S.; Weber, G.; Blumenfeld, W.; Frazer, S. 2010 State of Higher Education for LGBT; Campus Pride: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of the European Union. Guidelines to promote and to protect the enjoyment of all human rights by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) persons. In Proceedings of the FOREIG AFFAIRS Council Meeting, Luxembourg, 24 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S.J. Diversity and inclusivity at university: A survey of the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) students in the UK. High. Educ. 2009, 57, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodeo, A.L.; Esposito, C.; Bacchini, D. Heterosexist microaggressions, student academic experience and perception of campus climate: Findings from an Italian higher education context. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Pachankis, J.E. Stigma and Minority Stress as Social Determinants of Health Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 63, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice and Discrimination as Social Stressors. In The Health of Sexual Minorities; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 242–267. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, F.N.; Rostosky, S.S.; Danner, F. Stigma-related stressors, coping self-efficacy, and physical health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, B.A.; Goldfried, M.R.; Davila, J. The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 80, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.M.; Lehavot, K.; Meyer, I.H. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J.E.; Sullivan, T.J.; Feinstein, B.A.; Newcomb, M.E. Young Adult Gay and Bisexual Men’s Stigma Experiences and Mental Health: An 8-Year Longitudinal Study. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M.R.; Kulick, A. Academic and Social Integration on Campus Among Sexual Minority Students: The Impacts of Psychological and Experiential Campus Climate. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 55, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M.R.; Kulick, A.; Atteberry, B. Protective factors, campus climate, and health outcomes among sexual minority college students. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2015, 8, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, J.C.; Taylor, J.L.; Rankin, S. An Examination of Campus Climate for LGBTQ Community College Students. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2015, 39, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverschanz, P.; Cortina, L.M.; Konik, J.; Magley, V.J. Slurs, snubs, and queer jokes: Incidence and impact of heterosexist harassment in academia. Sex Roles 2008, 58, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M.R.; Han, Y.; Craig, S.; Lim, C.; Matney, M.M. Discrimination and Mental Health Among Sexual Minority College Students: The Type and Form of Discrimination Does Matter. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2014, 18, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, M.S.; Sontag-Padilla, L.; Ramchand, R.; Seelam, R.; Stein, B.D. Mental Health Service Utilization Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Questioning or Queer College Students. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, M.R.; Kulick, A.; Sinco, B.R.; Hong, J.S. Contemporary heterosexism on campus and psychological distress among LGBQ students: The mediating role of self-acceptance. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development—Urie Bronfenbrenner; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Terenzini, P.T. How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of Research; Jossey-Bass: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Colleges as communities: Taking research on student persistence seriously. Rev. High. Educ. 1998, 21, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Garvey, J.C.; Sanders, L.A.; Flint, M.A. Generational perceptions of campus climate among LGBTQ undergraduates. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2017, 58, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, A.L.; McGuire, J.K.; Stolz, C. Direct and indirect experiences with heterosexism: How slurs impact all students. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2018, 22, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M.R.; Howell, M.L.; Silverschanz, P.; Yu, L. That’s so gay!: Examining the covariates of hearing this expression among gay, lesbian, and bisexual college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2012, 60, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, M.R.; Gilmore, S. Assessing LGBTQ campus climate and creating change. J. Homosex. 2011, 58, 1330–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, T.R.; Lent, R.W. Heterosexist harassment and social cognitive variables as predictors of sexual minority college students’ academic satisfaction and persistence intentions. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenfeld, W.J.; Weber, G.N.; Rankin, S. In our own voice: Campus climate as a mediating factor in the persistence of LGBT students, faculty, and staff in higher education. In Queering Classrooms: Personal Narratives and Educational Practices to Support LGBTQ Youth in Schools; Chamness Miller, P., Mikulec, E., Eds.; Information Age Publishing Inc.: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, E.A. Validation Experiences and Persistence among Community College Students. Rev. High. Educ. 2010, 34, 193–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, J.C.; Squire, D.D.; Stachler, B.; Rankin, S. The impact of campus climate on queer-spectrum student academic success. J. LGBT Youth 2018, 15, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- ILGA-EUROPE. Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex People in Italy Covering the Period of January to December 2019; ILGA-EUROPE: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Di Battista, S.; Paolini, D.; Pivetti, M. Attitudes Toward Same-Sex Parents: Examining the Antecedents of Parenting Ability Evaluation. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingiardi, V.; Falanga, S.; D’Augelli, A.R. The Evaluation of Homophobia in an Italian Sample. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2005, 34, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingiardi, V.; Nardelli, N.; Ioverno, S.; Falanga, S.; Di Chiacchio, C.; Tanzilli, A.; Baiocco, R. Homonegativity in Italy: Cultural Issues, Personality Characteristics, and Demographic Correlates with Negative Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2016, 13, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, K.A. LGBT and Queer Research in Higher Education. Educ. Res. 2010, 39, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescorla, L.A.; Achenbach, T.M. The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) for Ages 18 to 90 Years. In The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment: Instruments for Adults; Maruish, M.E., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla, L.A.; Achenbach, T.M.; Ivanova, M.Y.; Turner, L.V.; Althoff, R.R.; Árnadóttir, H.A.; Au, A.; Bellina, M.; Caldas, J.C.; Chen, Y.-C.; et al. Problems and adaptive functioning reported by adults in 17 societies. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2016, 5, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Terenzini, P.T. Student-Faculty and Student-Peer Relationships as Mediators of the Structural Effects of Undergraduate Residence Arrangement. J. Educ. Res. 1980, 73, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B.O.; Du Toit, S.H.C.; Spisic, D. Robust Inference Using Weighted Least Squares and Quadratic Estimating Equations in Latent Variable Modeling with Categorical and Continuous Outcomes. Unpublished Technical Report. 1997. Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/download/Article_075.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, J.C.; Rankin, S.R. Making the grade? Classroom climate for LGBTQ students across gender conformity. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2015, 52, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinski, J.; Sexton, P. Still in the closet: The invisible minority in medical education. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldo, C.R. Out on campus: Sexual orientation and academic climate in a university context. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1998, 26, 745–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament & Council. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2000, 50, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bränström, R.; Pachankis, J.E. Sexual orientation disparities in the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress: A national population-based study (2008–2015). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plöderl, M.; Tremblay, P. Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Semlyen, J.; Tai, S.S.; Killaspy, H.; Osborn, D.; Popelyuk, D.; Nazareth, I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, S.B.; Wyatt, T.J. Sexual Orientation and Differences in Mental Health, Stress, and Academic Performance in a National Sample of U.S. College Students. J. Homosex. 2011, 58, 1255–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N = 868 N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sexual orientation | |

| LGB+ | 151 (17.5) |

| Other | 717 (82.5) |

| Gender identity | |

| Cisgender | 855 (98.5) |

| Genderqueer | 13 (1.5) |

| Family yearly income | |

| ≤15,000 | 436 (50.2) |

| 16,000≤ ≥50,000 | 347 (40) |

| ≥51,000 | 85 (9.8) |

| Participation in academic activities | |

| more than 75% of planned activities | 575 (66.3) |

| between 50% and 75% of planned activities | 201 (23.1) |

| between 25% and 50% of planned activities | 53 (6.1) |

| less than 25% of planned activities | 26 (3.0) |

| non-attending student | 13 (1.5) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family yearly income | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 0.07 * | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Biological sex (Male) | 0.07 * | 0.18 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Participation in academic activities | −0.02 | 0.18 ** | −0.05 | 1 | |||||

| 5. Sexual Minority status (LGBQ+) | −0.06 | −0.09 ** | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1 | ||||

| 6. Campus climate | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.23 *** | −0.13 * | 1 | |||

| 7. Intellectual and academic success | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.1 | 0 | 0.60 *** | 1 | ||

| 8. Having thought about leaving university (Yes) | −0.11 ** | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.11 ** | −0.51 *** | −0.26 *** | 1 | |

| 9. Anxiety–depression | −0.07 * | 0 | −0.20 *** | 0.05 | 0.18 *** | −0.48 *** | −0.27 *** | 0.35 *** | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amodeo, A.L.; Esposito, C.; Esposito, C.; Bacchini, D. Sexual Minority Status, Anxiety–Depression, and Academic Outcomes: The Role of Campus Climate Perceptions among Italian Higher Education Students. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120179

Amodeo AL, Esposito C, Esposito C, Bacchini D. Sexual Minority Status, Anxiety–Depression, and Academic Outcomes: The Role of Campus Climate Perceptions among Italian Higher Education Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2020; 10(12):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120179

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmodeo, Anna Lisa, Concetta Esposito, Camilla Esposito, and Dario Bacchini. 2020. "Sexual Minority Status, Anxiety–Depression, and Academic Outcomes: The Role of Campus Climate Perceptions among Italian Higher Education Students" Behavioral Sciences 10, no. 12: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120179

APA StyleAmodeo, A. L., Esposito, C., Esposito, C., & Bacchini, D. (2020). Sexual Minority Status, Anxiety–Depression, and Academic Outcomes: The Role of Campus Climate Perceptions among Italian Higher Education Students. Behavioral Sciences, 10(12), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120179