Circulating Lipid Peroxides Associate with More Aggressive Tumor Phenotypes and Increased Risks of Recurrence and Mortality in Breast Cancer Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

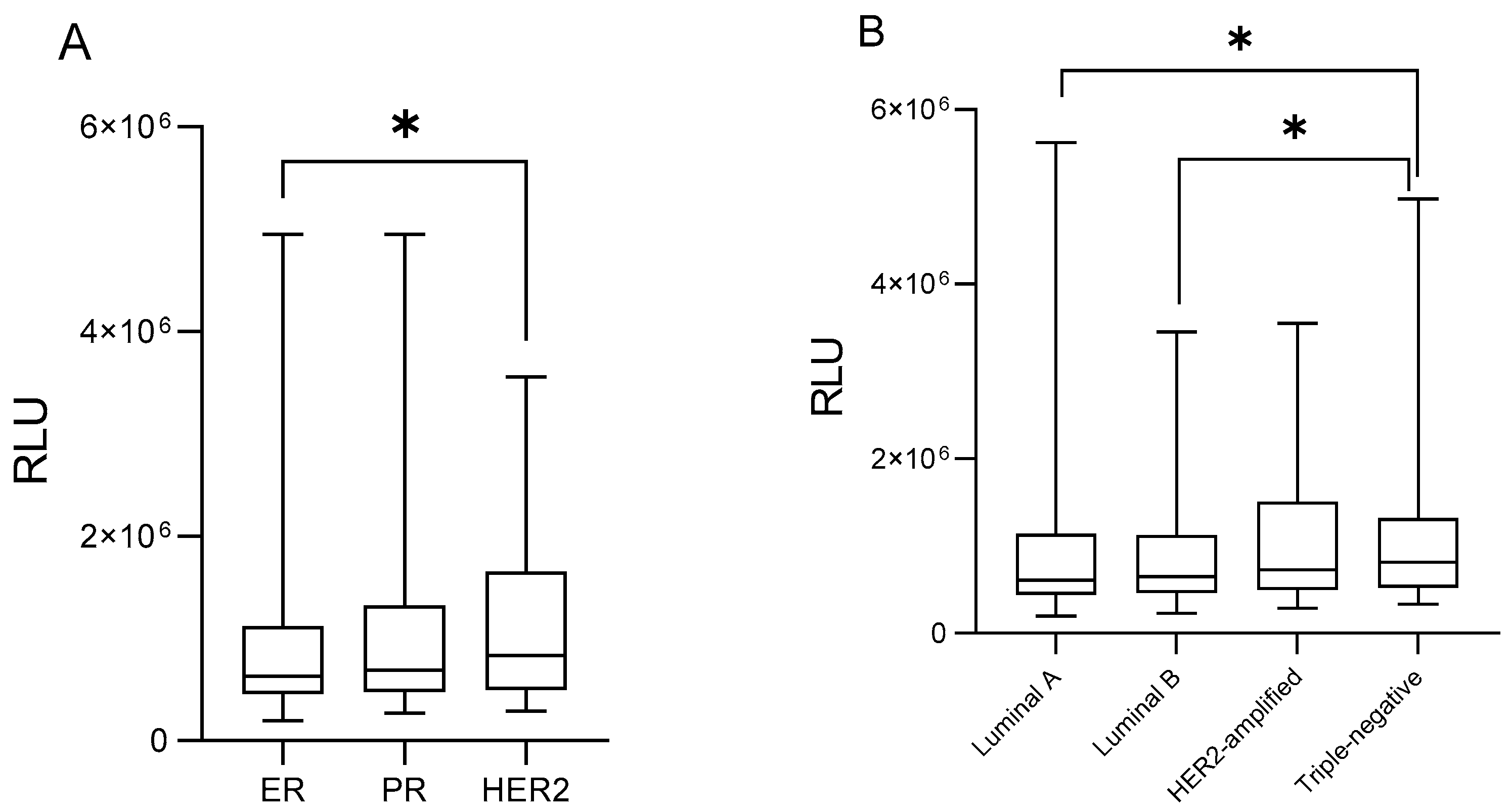

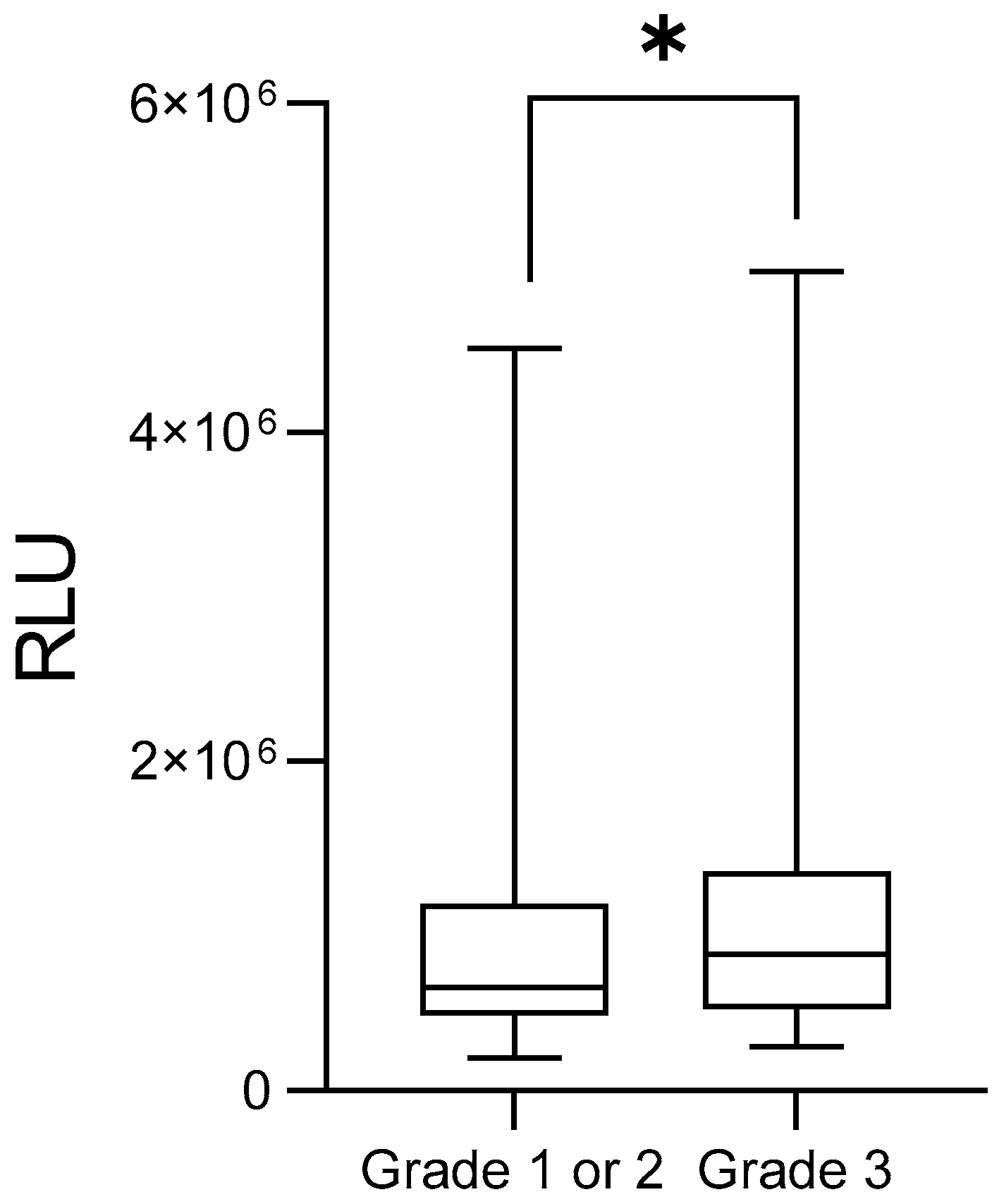

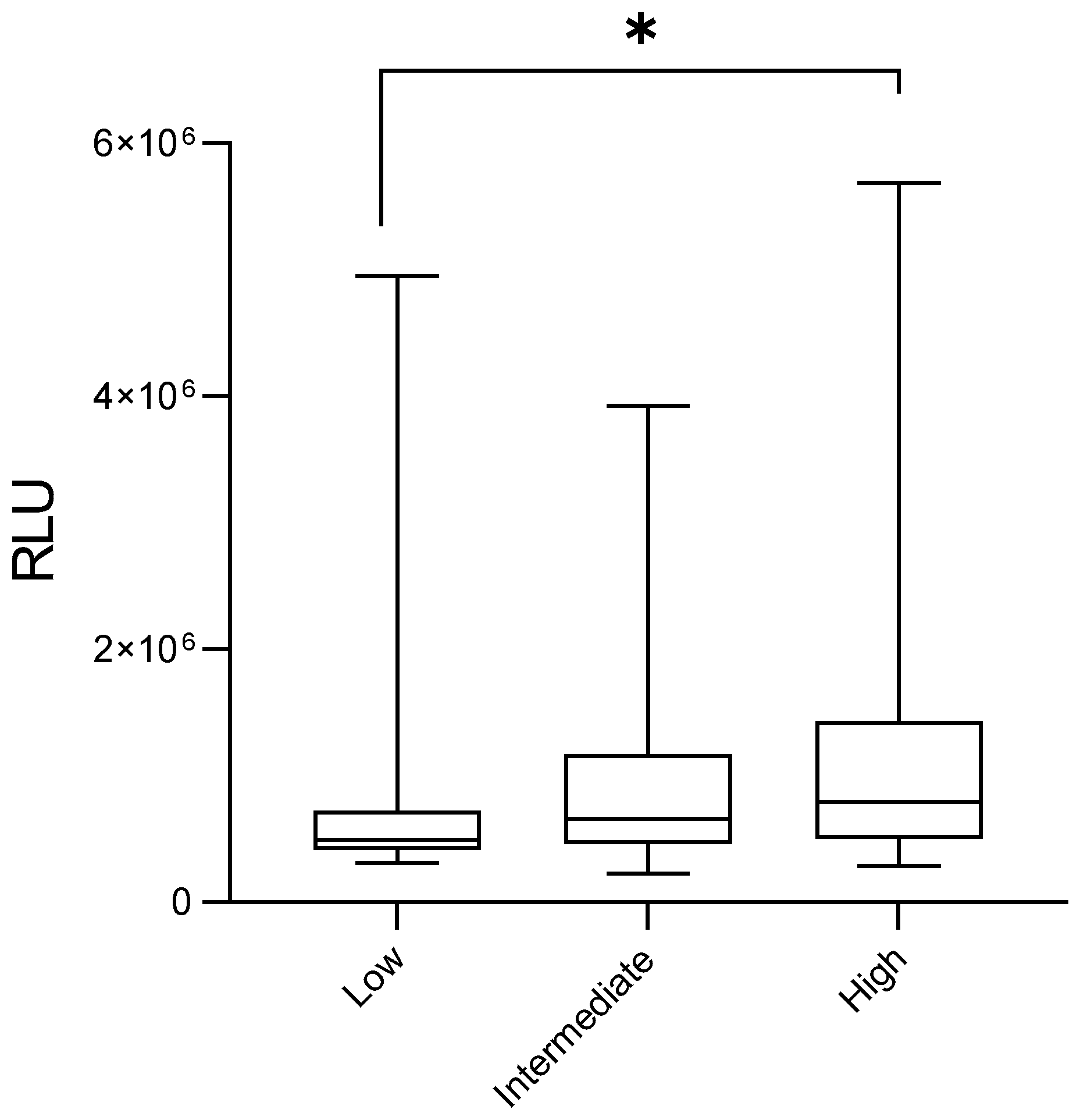

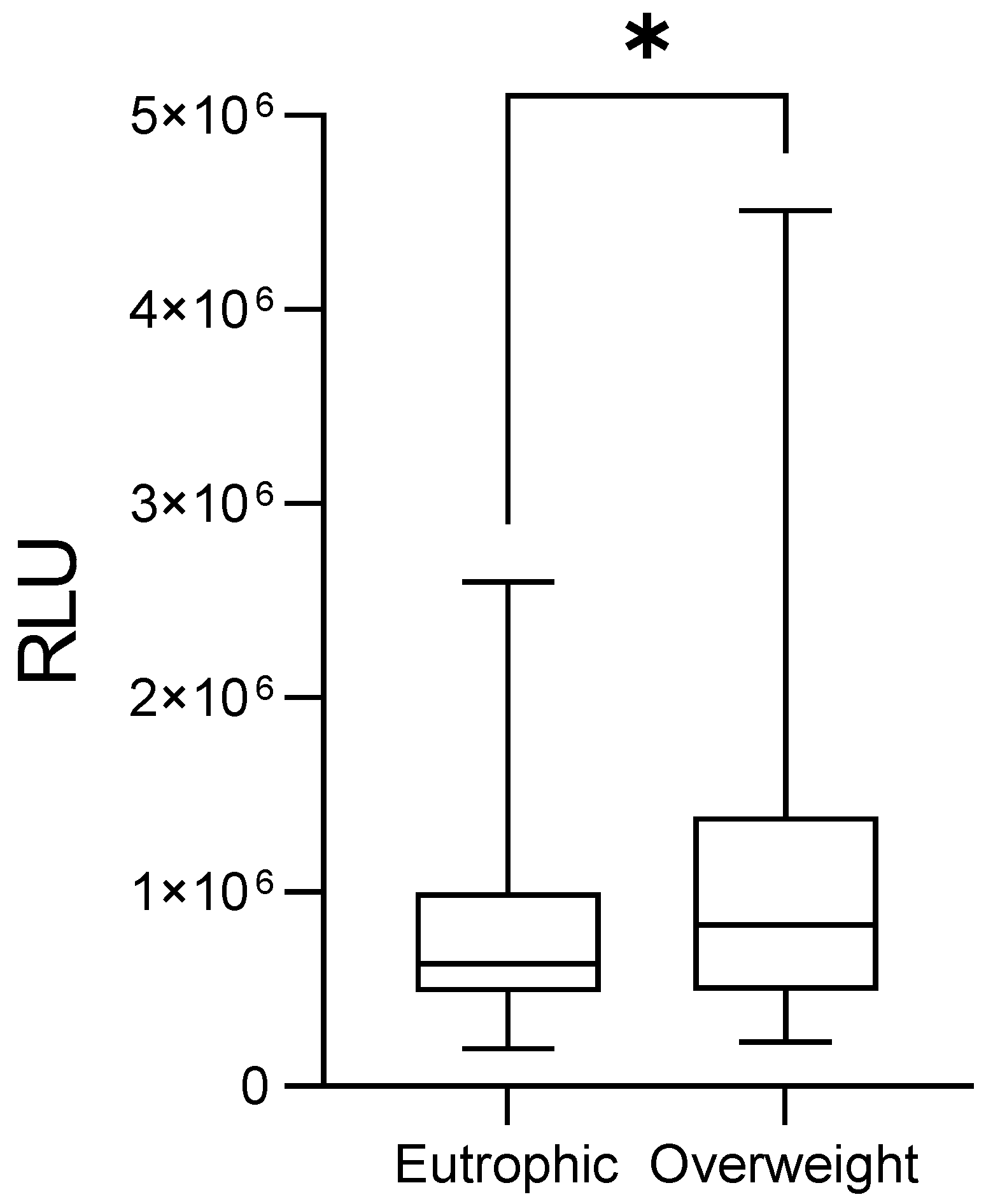

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABDM | Associação Beneficente Deus Menino |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| EU | Eutrophic |

| G1 | Histological Grade 1 |

| G2 | Histological Grade 2 |

| G3 | Histological Grade 3 |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HR | High Risk |

| LA | Luminal A |

| LB | Luminal B |

| LR | Low Risk |

| NR | Not reported |

| OW/OB | Overweight/Obese |

| PR | Progesterone Receptor |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RLU | Relative Light Unit |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TN | Triple Negative |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I. Inflammatory blood markers in breast cancer: A narrative review from early detection to therapy response. Ann. Med. Surg. 2025, 87, 5906–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel’skaya, L.V.; Dyachenko, E.I. Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer: A Biochemical Map of Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 4646–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Panis, C.; Victorino, V.J.; Herrera, A.C.S.A.; Cecchini, A.L.; Simão, A.N.C.; Tomita, L.Y.; Cecchini, R. Can breast tumors affect the oxidative status of the surrounding environment? A comparative analysis among cancerous breast, mammary adjacent tissue, and plasma. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 6429812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsonwu-Anyanwu, A.C.; Usoro, A.; Etuk, E.B.; Chukwuanukwu, R.C.; O Usoro, C.A. Evaluation of biomarkers of oxidative stress and female reproductive hormones in post menopausal women with breast cancer in Southern Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 24, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, A.C.S.; Victorino, V.J.; Campos, F.C.; Verenitach, B.D.; Lemos, L.T.; Aranome, A.M.; Oliveira, S.R.; Cecchini, A.L.; Simão, A.N.C.; Abdelhay, E.; et al. Impact of tumor removal on the systemic oxidative profile of patients with breast cancer discloses lipid peroxidation at diagnosis as a putative marker of disease recurrence. Clin. Breast Cancer 2014, 14, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Urbano-Polo, N.; Dueñas, B.; Navarro-Cecilia, J.; Ramírez-Tortosa, C.; Martín-Salvago, M.D.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Redox status in the sentinel lymph node of women with breast cancer. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 122, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kasapović, J.; Pejić, S.; Stojiljković, V.; Todorović, A.; Radošević-Jelić, L.; Saičić, Z.S.; Pajović, S.B. Antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in the blood of breast cancer patients of different ages after chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Clin. Biochem. 2010, 43, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panis, C.; Herrera, A.C.S.A.; Victorino, V.J.; Campos, F.C.; Freitas, L.F.; De Rossi, T.; Simão, A.N.C.; Cecchini, A.L.; Cecchini, R. Oxidative stress and hematological profiles of advanced breast cancer patients subjected to paclitaxel or doxorubicin chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 133, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhirsch, A.; Wood, W.C.; Coates, A.S.; Gelber, R.D.; Thürlimann, B.; Senn, H.J. Strategies for subtypes—Dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: Highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 1736–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer. 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, B.G.; Llesuy, S.; Boveris, A. Hydroperoxide-initiated chemiluminescence: An assay for oxidative stress in biopsies of heart, liver, and muscle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991, 10, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.M.; Jaques, H.S.; Orrutéa, J.F.G.; de Oliveira Silva, A.G.; Machado, M.G.; Smaniotto, L.L.; Federige, A.C.L.; Colleto, M.I.O.; Souza, J.A.O.; Rech, D.; et al. Changes in systemic oxidative stress correlate to chemoresistance and poor prognosis features in women with breast cancer. Rev. Senol. Patol. Mamar. 2024, 37, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.B.C.; Jaques, H.S.; Ferronato, M.; Alves, F.M.; Colleto, M.I.; Ferreira, M.O.; Orrutéa, J.F.; Mezzoni, M.; Silva, R.G.S.; Rech, D.; et al. Excess body weight significantly affects systemic and tumor inflammatory status and correlates to poor prognosis parameters in patients with breast cancer. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2023, 4, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buettner, G.R.; Wagner, B.A.; Rodgers, V.G. Quantitative redox biology: An approach to understand the role of reactive species in defining the cellular redox environment. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 67, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakh, S.; Gan, H.K.; Parslow, A.C.; Burvenich, I.J.; Burgess, A.W.; Scott, A.M. Evolution of anti-HER2 therapies for cancer treatment. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 59, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.L.; Silva, A.T.; Ferreira, I.C.; Souza, A.V.; Justino, A.B.; Santos, D.W.; Goulart, L.R.; Paiva, C.E.; Espíndola, F.S.; Maia, Y.C. A lower serum antioxidant capacity as a distinctive feature for women with HER2+ breast cancer: A Preliminary Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, Z.; Desai, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Pannell, L.K.; Yi, H.; Wright, E.R.; Owen, L.B.; Dean-Colomb, W.; et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB2 translocates into mitochondria and regulates cellular metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotna, E.; Milosevic, M.; Prukova, D.; Magalhaes-Novais, S.; Dvorakova, S.; Dmytruk, K.; Gemperle, J.; Zudova, D.; Nickl, T.; Vrbacky, M.; et al. Mitochondrial HER 2 stimulates respiration and promotes tumorigenicity. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 54, E14174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouki, M.M.; Kulawiec, M.; Bansal, S.; Das, G.M.; Singh, K.K. Cross talk between mitochondria and superoxide generating NADPH oxidase in breast and ovarian tumors. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005, 4, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, P.; Ramos, S.; Oliveira, M.J.; Costa, J.G.; Saraiva, N.; Fernandes, A.S. Interaction between redox regulation, immune activation, and response to treatment in HER2+ breast cancer. Redox. Biol. 2025, 82, 103609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badve, S.; Dabbs, D.J.; Schnitt, S.J.; Baehner, F.L.; Decker, T.; Eusebi, V.; Fox, S.B.; Ichihara, S.; Jacquemier, J.; Lakhani, S.R.; et al. Basal-like and triple-negative breast cancers: A critical review with an emphasis on the implications for pathologists and oncologists. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelicano, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Hammoudi, N.; Dai, J.; Xu, R.H.; Huang, P. Mitochondrial respiration defects in cancer cells cause activation of Akt survival pathway through a redox-mediated mechanism. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento-Salinas, F.L.; Delgado-Magallón, A.; Montes-Alvarado, J.B.; Ramírez-Ramírez, D.; Flores-Alonso, J.C.; Cortés-Hernández, P.; Reyes-Leyva, J.; Herrera-Camacho, I.; Anaya-Ruiz, M.; Pelayo, R.; et al. Breast Cancer Subtypes Present a Differential Production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Susceptibility to Antioxidant Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2019, 7, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Haq, A.T.; Tseng, H.Y.; Chen, L.M.; Wang, C.C.; Hsu, H.L. Targeting prooxidant MnSOD effect inhibits triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) progression and M2 macrophage functions under the oncogenic stress. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Oshi, M.; Asaoka, M.; Yan, L.; Endo, I.; Takabe, K. Molecular Biological Features of Nottingham Histological Grade 3 Breast Cancers. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 4475–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpi, A.; Bacci, F.; Paradiso, A.; Saragoni, L.; Scarpi, E.; Ricci, M.; Aldi, M.; Bianchi, S.; Muretto, P.; Nuzzo, F.; et al. Prognostic relevance of histological grade and its components in node-negative breast cancer patients. Mod. Pathol. 2004, 17, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Kabeer, A.; Abbas, Z.; Siddiqui, H.A.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cho, W.C. Interplay of oxidative stress, cellular communication and signaling pathways in cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Ma, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, M. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic innovations. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2025, 30, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqubal, A.; Haque, S.E. Molecular Mechanism of Oxidative Stress in Cancer and Its Therapeutics. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines—Breast Cancer; Federal District: Brasília, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Saintot, M.; Mathieu-Daude, H.; Astre, C.; Grenier, J.; Simony-Lafontaine, J.; Gerber, M. Oxidant-antioxidant status in relation to survival among breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 97, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, S.; Fujita, T.; Shimabukuro, M.; Iwaki, M.; Yamada, Y.; Nakajima, Y.; Nakayama, O.; Makishima, M.; Matsuda, M.; Shimomura, I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marseglia, L.; Manti, S.; D’Angelo, G.; Nicotera, A.; Parisi, E.; Di Rosa, G.; Gitto, E.; Arrigo, T. Oxidative stress in obesity: A critical component in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 16, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Nino, M.E. The role of chronic inflammation in obesity-associated cancers. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2013, 2013, 697521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Sánchez, A.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Bautista, M.; Esquivel-Soto, J.; Morales-González, Á.; Esquivel-Chirino, C.; Durante-Montiel, I.; Sánchez-Rivera, G.; Valadez-Veja, C.; Morales-González, J.A. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 3117–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, I.; Le, N.; Asif, A.; Goulding, A.; Alcantara, C.A.; Vu, A.; Chorbajian, A.; Mirhosseini, M.; Singh, M.; Venketaraman, V. The Role of Obesity in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis. Cells 2023, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, B.; Iiritano, S.; Nocera, A.; Possidente, K.; Nevolo, M.T.; Ventura, V.; Foti, D.; Chiefari, E.; Brunetti, A. Insulin resistance and cancer risk: An overview of the pathogenetic mechanisms. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012, 2012, 789174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Negative lymph nodes and all the following criteria: | |

| pT under 2 cm; | |

| Low risk | Histological grade 1; |

| ER- or PR-positive; | |

| HER-2-negative; | |

| Molecular subtype luminal A; and | |

| Age equal or above 35 years old. | |

| Negative lymph nodes and at least one of the following criteria: | |

| pT higher than 2 cm; or | |

| Histological grade 2–3; or ER- or PR-negative; or | |

| Intermediate risk | Molecular subtype luminal B (HER-2-negative); or |

| Age under 35 years old; or yet | |

| 1 to 3 affected lymph nodes. If ER- and PR-positive. | |

| 4 or more positive lymph nodes; or | |

| High risk | Lymph nodes negative with ER. PR- and HER-2-negative. pT higher than 2 cm; or |

| Lymph node negative. pT higher than 1 cm and HER-2-positive. |

| Number of Breast Cancer Patients in the Study | N = 408 |

|---|---|

| Estrogen receptor | |

| No | 28.70% |

| Yes | 71.30% |

| Progesterone receptor | |

| No | 50.00% |

| Yes | 50.00% |

| HER2 receptor | |

| No | 83.60% |

| Yes | 16.40% |

| Ki-67 proliferation index | |

| <14% | 35.80% |

| ≥14% | 61.50% |

| NR | 2.70% |

| Molecular subtype | |

| Luminal A | 28.70% |

| Luminal B | 37.00% |

| HER-2-amplified | 13.50% |

| Triple-negative | 18.90% |

| NR | 1.90% |

| Risk of death/recurrence | |

| Low | 7.40% |

| Intermediate | 52.40% |

| High | 31.90% |

| NR | 8.30% |

| Tumor size | |

| ≤2 cm | 44.90% |

| >2 cm | 51.20% |

| NR | 3.90% |

| Histological grade | |

| Grades 1 and 2 | 74.30% |

| Grades 3 | 22.00% |

| NR | 3.70% |

| Intratumoral emboli | |

| No | 75.20% |

| Yes | 21.30% |

| NR | 3.50% |

| Lymph node metastasis | |

| No | 66.20% |

| Yes | 29.90% |

| NR | 3.90% |

| Distant metastasis | |

| No | 72.30% |

| Yes | 6.40% |

| NR | 21.30% |

| Age at diagnosis | |

| <50 years | 33.30% |

| ≥50 years | 61.50% |

| NR | 5.20% |

| Menopause at diagnosis | |

| No | 41.40% |

| Yes | 50.70% |

| NR | 7.90% |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | |

| Eutrophic | 21.10% |

| Overweight | 56.90% |

| NR | 22% |

| Chemoresistance | |

| No | 83.10% |

| Yes | 16.90% |

| Recurrence | |

| No | 90.20% |

| Yes | 9.80% |

| Deceased | |

| No | 94.40% |

| Yes | 5.60% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Orrutéa, J.F.G.; Matos, R.O.; Pinto, J.P.A.; Cechinel, A.C.; Koizumi, B.Y.; Paz, R.G.; Almeida, R.F.; da Silva, J.C.; Fagundes, T.R.; Rech, D.; et al. Circulating Lipid Peroxides Associate with More Aggressive Tumor Phenotypes and Increased Risks of Recurrence and Mortality in Breast Cancer Patients. Med. Sci. 2026, 14, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010043

Orrutéa JFG, Matos RO, Pinto JPA, Cechinel AC, Koizumi BY, Paz RG, Almeida RF, da Silva JC, Fagundes TR, Rech D, et al. Circulating Lipid Peroxides Associate with More Aggressive Tumor Phenotypes and Increased Risks of Recurrence and Mortality in Breast Cancer Patients. Medical Sciences. 2026; 14(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrrutéa, Julia Fernandes Gois, Rafaela Oliveira Matos, João Paulo Araújo Pinto, André Cherubini Cechinel, Bruna Yukie Koizumi, Rafael Gomes Paz, Rafaella Frederico Almeida, Janaína Carla da Silva, Tatiane Renata Fagundes, Daniel Rech, and et al. 2026. "Circulating Lipid Peroxides Associate with More Aggressive Tumor Phenotypes and Increased Risks of Recurrence and Mortality in Breast Cancer Patients" Medical Sciences 14, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010043

APA StyleOrrutéa, J. F. G., Matos, R. O., Pinto, J. P. A., Cechinel, A. C., Koizumi, B. Y., Paz, R. G., Almeida, R. F., da Silva, J. C., Fagundes, T. R., Rech, D., Welter Wendt, G., & Panis, C. (2026). Circulating Lipid Peroxides Associate with More Aggressive Tumor Phenotypes and Increased Risks of Recurrence and Mortality in Breast Cancer Patients. Medical Sciences, 14(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010043