In Silico Investigation Reveals IL-6 as a Key Target of Asiatic Acid in Osteoporosis: Insights from Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

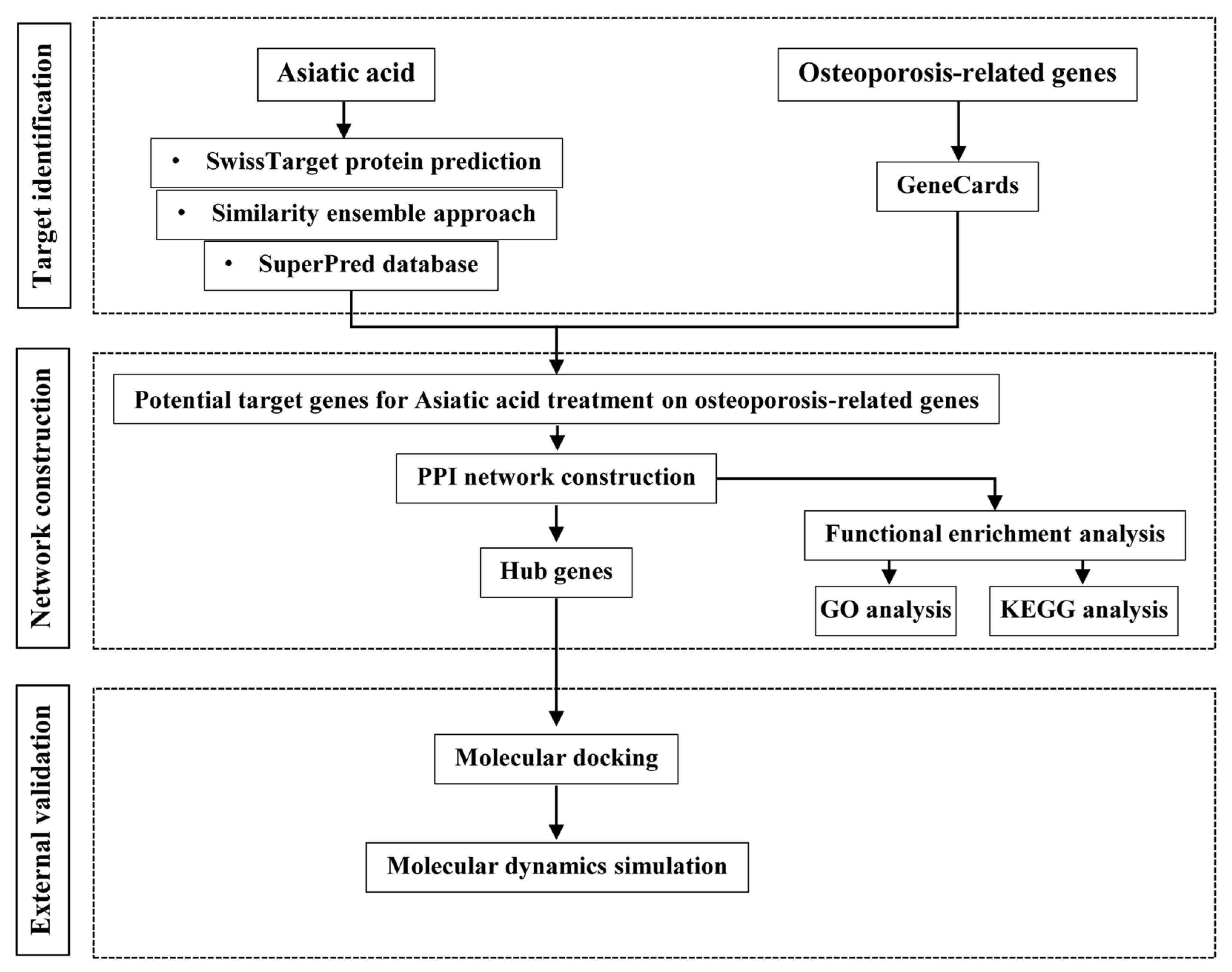

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Network Pharmacology Analysis

2.1.1. Prediction of Asiatic Acid and Osteoporosis Targets

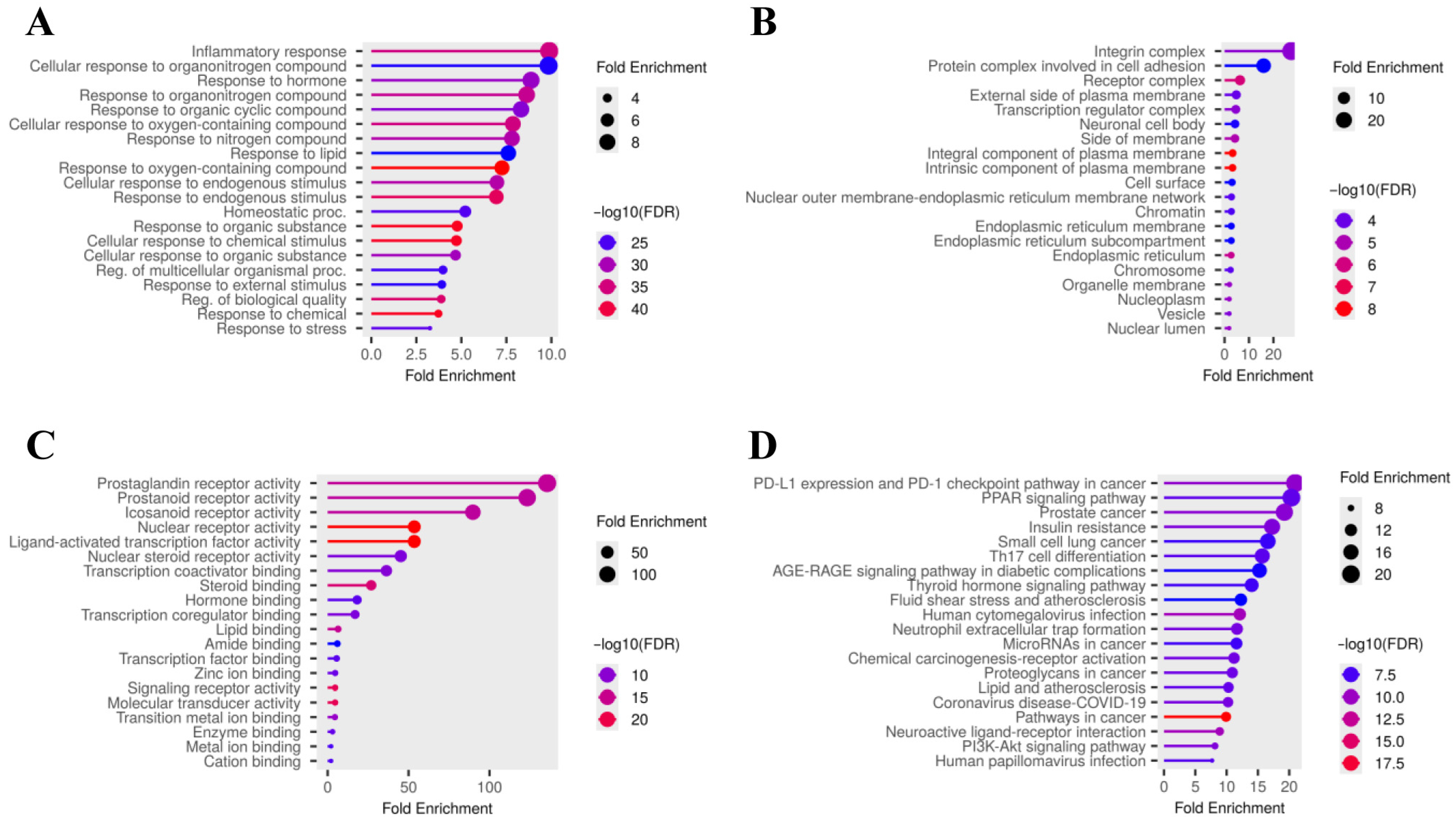

2.1.2. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.1.3. Construction of Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network

2.2. Molecular Docking

2.2.1. Protein Preparation

2.2.2. Ligand Preparation

2.2.3. Docking Protocol

2.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3. Results

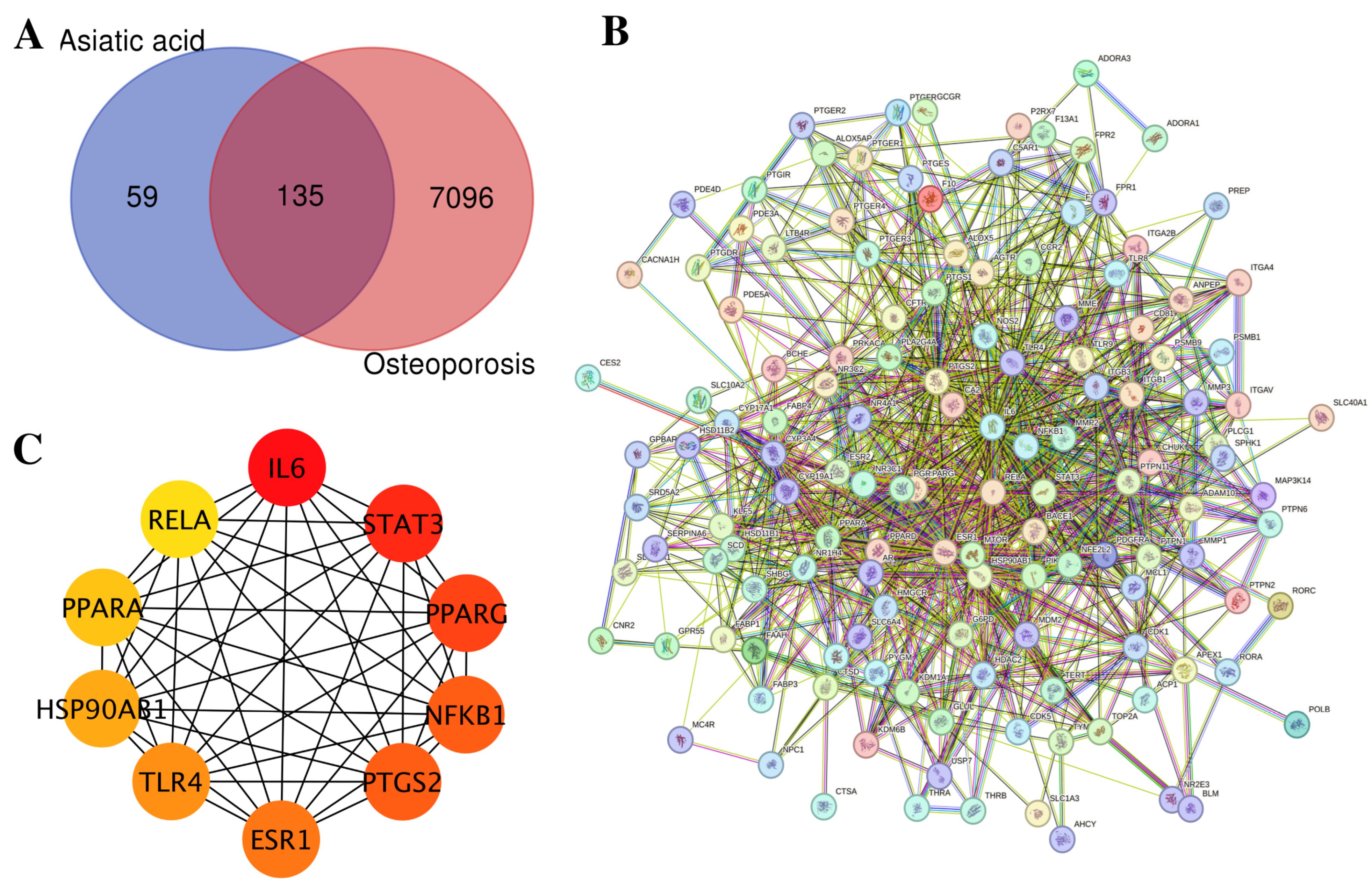

3.1. Network Pharmacology Analysis of Asiatic Acid Targets Related to Osteoporosis

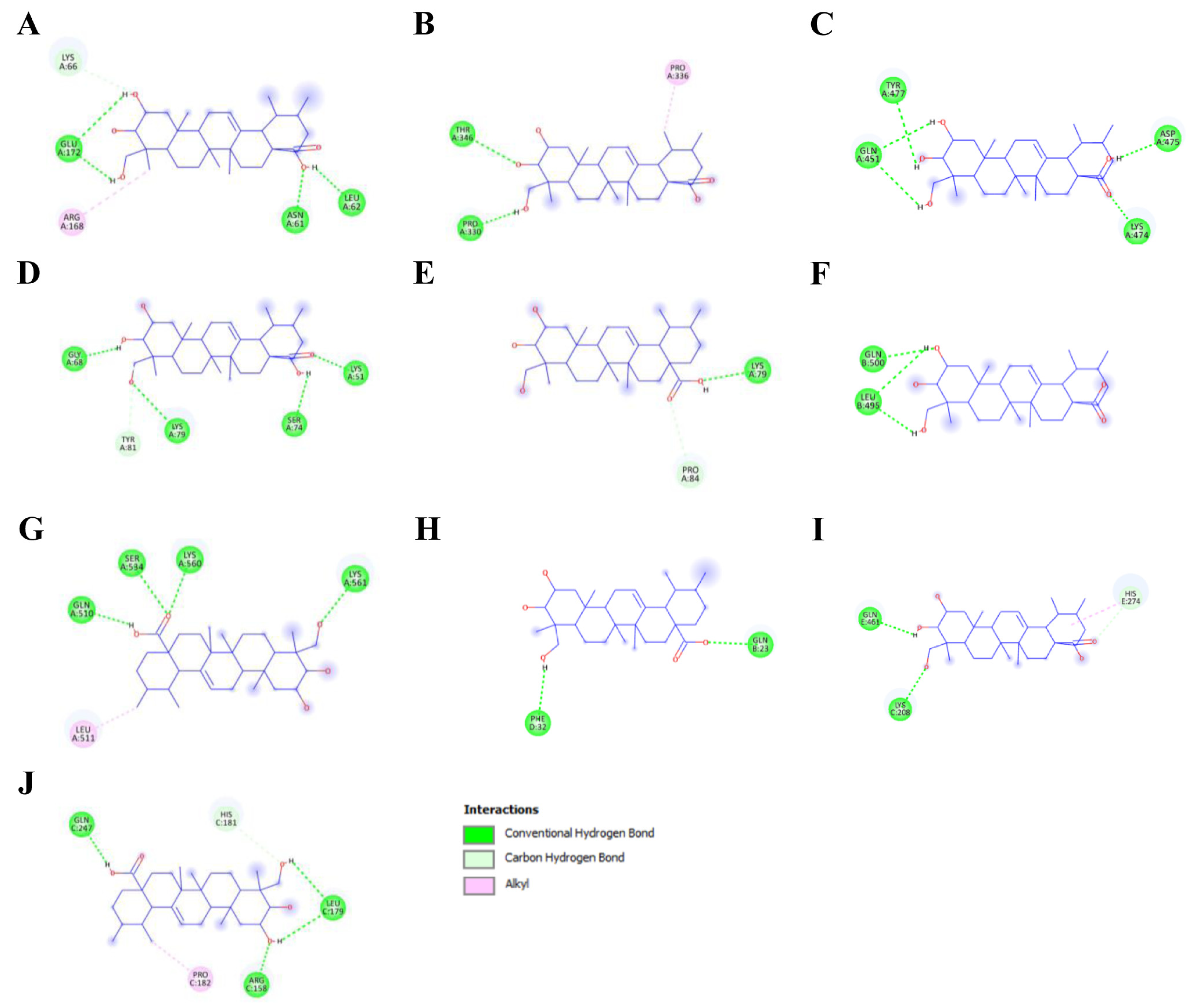

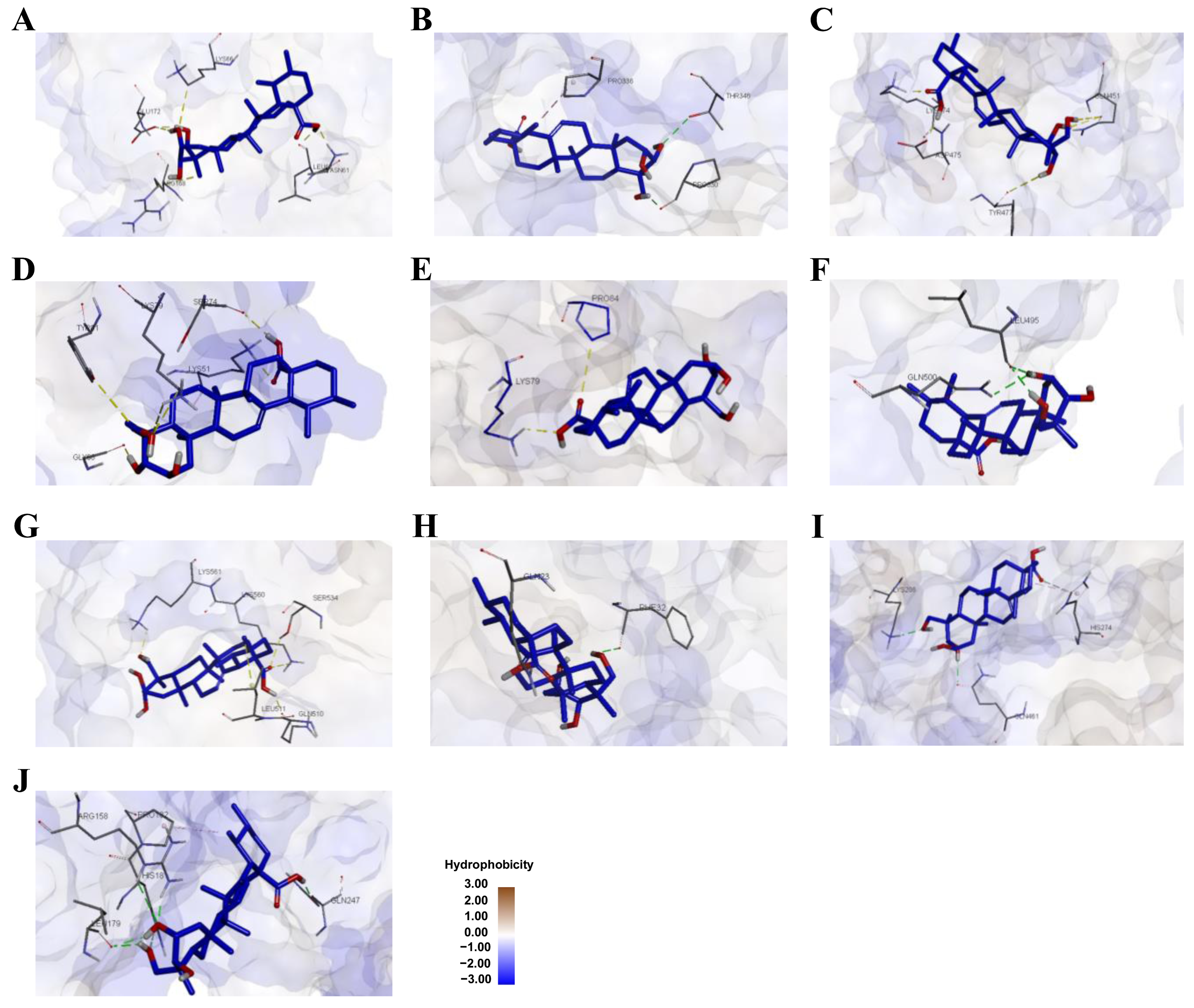

3.2. Molecular Docking Analysis of Asiatic Acid with Osteoporosis-Related Proteins

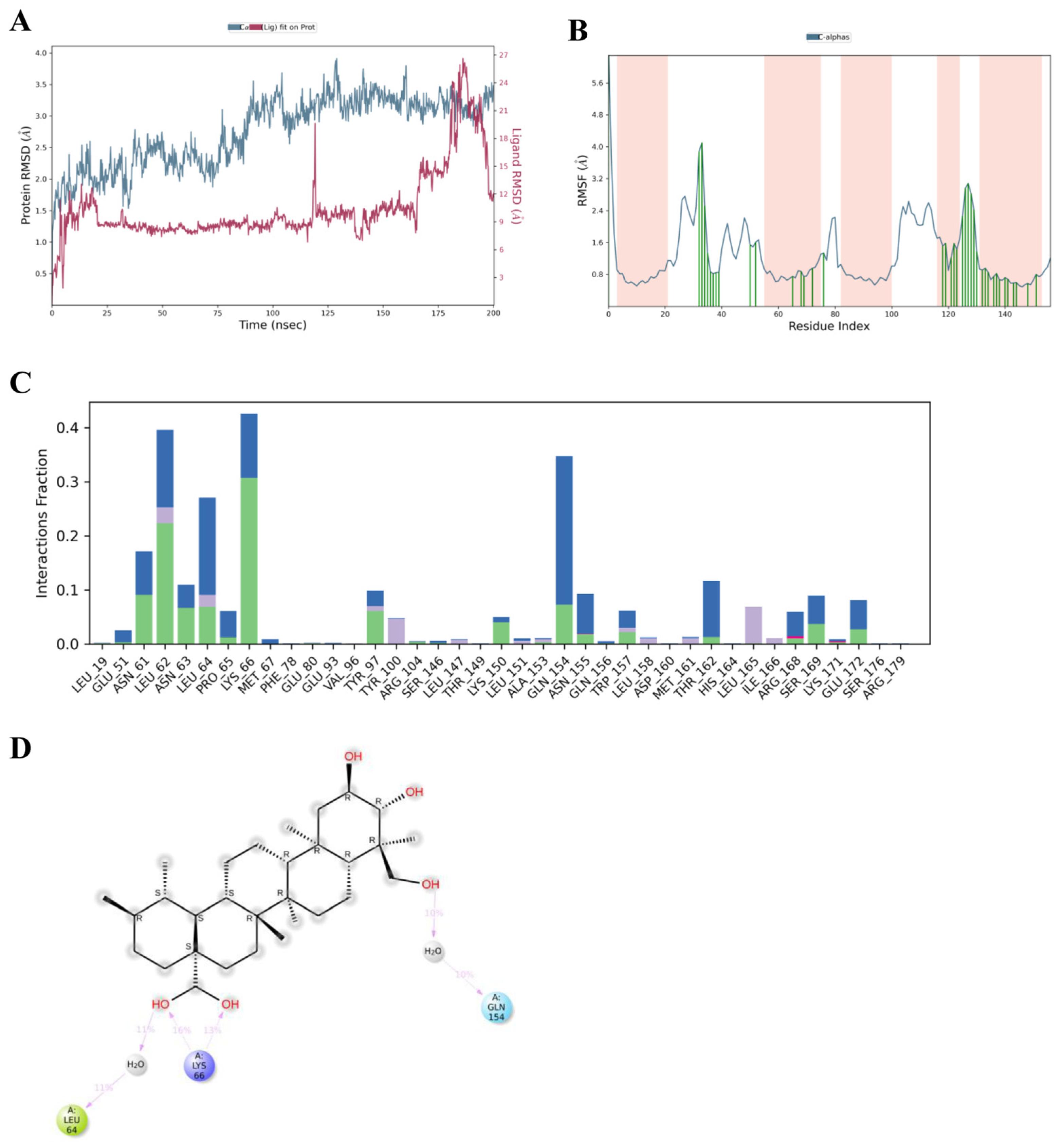

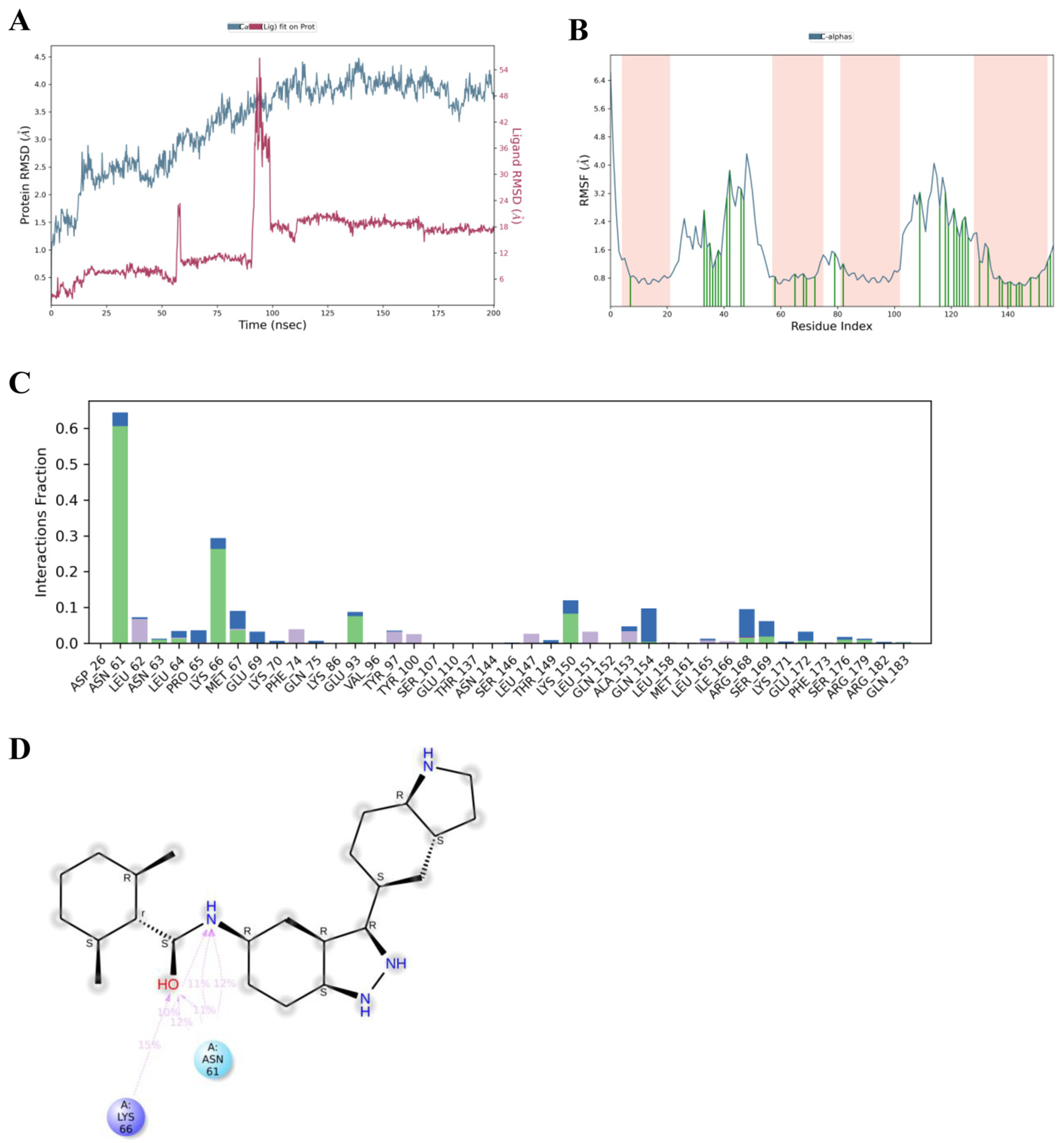

3.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Asiatic Acid and IL-6

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Å | Angström |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| ΔG | Binding free energy |

| ESRα | Estrogen receptor alpha |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GAFF | General AMBER force field |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HSP90AB1 | Heat shock protein 90 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-6Rα | Interleukin-6 receptor alpha |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Ki | Inhibitory constant |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| RANKL | Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| RMSF | Root mean square fluctuation |

| SEA | Similarity Ensemble Approach |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| STRING | Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

References

- Rachner, T.D.; Khosla, S.; Hofbauer, L.C. Osteoporosis: Now and the future. Lancet 2011, 377, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compston, J.E.; McClung, M.R.; Leslie, W.D. Osteoporosis. Lancet 2019, 393, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-H.; Chen, L.-R.; Chen, K.-H. Primary Osteoporosis induced by androgen and estrogen deficiency: The molecular and cellular perspective on pathophysiological mechanisms and treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginaldi, L.; Di Benedetto, M.C.; De Martinis, M. Osteoporosis, inflammation and ageing. Immun. Ageing 2005, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Du, L.; Zhang, L.; Ding, L.; Xu, W.; Lin, X. The critical role of toll-like receptor 4 in bone remodeling of osteoporosis: From inflammation recognition to immunity. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1333086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, C.; De Martino, E.; Scapato, P. Osteoporosis: Focus on bone remodeling and disease types. BioChem 2025, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, L.; Liu, F.; Wan, L.; Deng, Z. The effect of cytokines on osteoblasts and osteoclasts in bone remodeling in osteoporosis: A review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1222129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Huang, D.; Ji, Y.; Kang, F. IL-6 enhances osteocyte-mediated osteoclastogenesis by promoting JAK2 and RANKL activity in vitro. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 41, 1360–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, B.F.; Li, J.; Yao, Z.; Xing, L. Nuclear factor-kappa B regulation of osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 38, 504–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, M.; Sousa, K.M.; MacDougald, O.A.; Rosen, C.J. The many facets of PPARgamma: Novel insights for the skeleton. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 299, E3–E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimai, H.P.; Fahrleitner-Pammer, A. Osteoporosis and fragility fractures: Currently available pharmacological options and future directions. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022, 36, 101780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.N.; Lie, J.D.; Wan, C.K.V.; Cameron, M.; Austel, A.G.; Nguyen, J.K.; Van, K.; Hyun, D. Osteoporosis: A review of treatment options. P&T 2018, 43, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, B. Natural products for treatment of osteoporosis: The effects and mechanisms on promoting osteoblast-mediated bone formation. Life Sci. 2016, 147, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.T.; Dubery, I.A. Pentacyclic triterpenoids from the medicinal herb, Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. Molecules 2009, 14, 3922–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qin, L.; Hayashi, M.; Kudo, M.; Gao, M.; Liu, T. Therapeutic potential of Centella asiatica and its triterpenes: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 568032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandopadhyay, S.; Mandal, S.; Ghorai, M.; Jha, N.K.; Kumar, M.; Radha; Ghosh, A.; Proćków, J.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Dey, A. Therapeutic properties and pharmacological activities of asiaticoside and madecassoside: A review. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.W.; Piao, C.D.; Sun, H.H.; Ren, X.S.; Bai, Y.S. Asiatic acid inhibits adipogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 68, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Zeng, J.; Yang, C.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, X. Asiatic acid attenuates osteoporotic bone loss in ovariectomized mice through inhibiting NF-kappaB/MAPK/Protein Kinase B signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 829741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, C.; Mamdouh, Z.M.; List, M.; Kiel, C.; Casas, A.I.; Schmidt, H.H.H.W. Network pharmacology: Curing causal mechanisms instead of treating symptoms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.Y.; Zhang, H.X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular docking: A powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2011, 7, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, R. Current experimental methods for characterizing protein-protein interactions. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 738–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, J.; Marsili, M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electronegativity—A rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron 1980, 36, 3219–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, M.C.; Daggett, V. Validating molecular dynamics simulations against experimental observables in light of underlying conformational ensembles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 6673–6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Ren, G.; Li, Y.; Hao, D. Network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation to explore the mechanism of kaempferol in the treatment of osteoporosis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Chai, K.; Liu, J.; Lei, H.; Lu, P.; et al. Network pharmacology: A crucial approach in traditional Chinese medicine research. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Zhou, L.; Han, X.; Sun, P.; Chen, Z.; He, W.; Tickner, J.; Chen, L.; Shi, X.; Xu, J. Asiatic acid inhibits OVX-induced osteoporosis and osteoclastogenesis via regulating RANKL-mediated NF-κB and Nfatc1 signaling pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, M.; Zong, Z.; Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Lan, H.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Lee, Y.W.; et al. Asiatic acid attenuates bone loss by regulating osteoclastic differentiation. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2019, 105, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ni, B.; Li, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, W. Association between postmenopausal osteoporosis and IL-6, TNF-α: A Systematic review and a meta-analysis. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2024, 27, 2260–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.S.; Wang, Y.Y.; Huang, X.W.; Wang, X.P.; Gao, M.; Li, B. Epimedium brevicornum Maxim alleviates diabetes osteoporosis by regulating AGE–RAGE signaling pathway. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Z.; Luo, J.; Peng, B.; Wang, Z. Research on the role and mechanism of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in osteoporosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1541714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Qi, L.; Wang, Y.; Ren, S. The participation of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) in the progression of osteoporosis via JAK/STAT pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 3819–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corry, K.A.; Zhou, H.; Brustovetsky, T.; Himes, E.R.; Bivi, N.; Horn, M.R.; Kitase, Y.; Wallace, J.M.; Bellido, T.; Brustovetsky, N.; et al. Stat3 in osteocytes mediates osteogenic response to loading. Bone Rep. 2019, 11, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Khayyat, S.G.; D’Alessandro, R.; Conticini, E.; Pierguidi, S.; Falsetti, P.; Baldi, C.; Bardelli, M.; Gentileschi, S.; Nicosia, A.; Frediani, B. Bone-sparing effects of tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis: A monocentric observational study. Reumatologia 2022, 60, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, D.P.; Kuruvilla, D.S.; Boregowda, S.V.; Asteian, A.; Hughes, T.S.; Garcia-Ordonez, R.; Corzo, C.A.; Khan, T.M.; Novick, S.J.; Park, H.; et al. Pharmacological repression of PPARγ promotes osteogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.D.; Jing, J.; Wang, J.W.; Mo, Y.Q.; Li, Q.H.; Lin, J.Z.; Chen, L.F.; Shao, L.; Miossec, P.; Dai, L. Activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1β/NFATc1 pathway in circulating osteoclast precursors associated with bone destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, T.; Yao, Z.; Li, F.; Zhang, Q.; Badell, I.R.; Schwarz, E.M.; Takeshita, S.; Wagner, E.F.; Noda, M.; Matsuo, K.; et al. NF-κB p50 and p52 regulate receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) and tumor necrosis factor-induced osteoclast precursor differentiation by activating c-Fos and NFATc1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 18245–18253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimi, E.; Aoki, K.; Saito, H.; D’Acquisto, F.; May, M.J.; Nakamura, I.; Sudo, T.; Kojima, T.; Okamoto, F.; Fukushima, H.; et al. Selective inhibition of NF-κB blocks osteoclastogenesis and prevents inflammatory bone destruction in vivo. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ivashkiv, L.B. Negative regulation of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption by cytokines and transcriptional repressors. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paggi, J.M.; Pandit, A.; Dror, R.O. The art and science of molecular docking. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2024, 93, 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.K.; Adnan, M.; Cho, D.H. Drug investigation to dampen the comorbidity of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis via molecular docking test. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 1046–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Muhammad, S.; Irfan, M.; Belali, T.; Chaudhry, A.R.; Khan, D.-M. Discovery of potential natural STAT3 inhibitors: An in silico molecular docking and molecular dynamics study. J. Comput. Biophys. Chem. 2023, 23, 2350058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimi, E.; Katagiri, T. Critical roles of NF-κB signaling molecules in bone metabolism revealed by genetic mutations in osteopetrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantarawong, S.; Swangphon, P.; Lauterbach, N.; Panichayupakaranant, P.; Pengjam, Y. Modified curcuminoid-rich extract liposomal CRE-SD inhibits osteoclastogenesis via the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.L.; Baeuerle, P.A. The p65 subunit is responsible for the strong transcription activating potential of NF-κB. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 3805–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, J.D.; McCammon, J.A. Molecular dynamics simulations and drug discovery. BMC Biol. 2011, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammacher, A.; Ward, L.D.; Weinstock, J.; Treutlein, H.; Yasukawa, K.; Simpson, R.J. Structure-function analysis of human IL-6: Identification of two distinct regions that are important for receptor binding. Protein Sci. 1994, 3, 2280–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Xiao, Z.; Suman, S.; Cooper, C.; Ha, K.; Carson, J.A.; Gupta, M. Structure-Based Design of Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Human Interleukin-6. Molecules 2025, 30, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, C.A.; Jones, S.A. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Cai, J.; Jiang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Meng, Z.; Xiao, H.; Chen, G.; Qiao, C.; Luo, L.; Yu, J.; et al. Unveiling novel insights into human IL-6 − IL-6R interaction sites through 3D computer-guided docking and systematic site mutagenesis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, H.H.; El-Esseily, H.A.; Ahmed, M.A.E.L.R.; Khamis Mohamed, M.A.; Roushdy, M.N.; ElSherif, A.; Gharbeya, K.M.; Abdelsalam, H.S. Targeting asparagine and cysteine in SARS-CoV-2 variants and human pro-inflammatory mediators to alleviate COVID-19 severity; A cross-section and in-silico study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagoor Meeran, M.F.; Goyal, S.N.; Suchal, K.; Sharma, C.; Patil, C.R.; Ojha, S.K. Pharmacological properties, molecular mechanisms, and pharmaceutical development of asiatic acid: A pentacyclic triterpenoid of therapeutic promise. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, F.B.; Asfaw, T.B.; Tadesse, M.G.; Gonfa, Y.H.; Bachheti, R.K. In silico studies as support for natural products research. Medinformatics 2025, 2, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xiong, P.; Cheng, L.; Ma, J.; Wen, Y.; Shen, T.; He, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Integrated network pharmacology, metabolomics, and transcriptomics of Huanglian–Hongqu herb pair in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 325, 117828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, I.I.; Fatoki, T.H.; Alonge, A.S.; Saliu, I.O.; Odesanmi, O.E.; Akinyelu, J.; Oke, O.E. ADME, molecular targets, docking, and dynamic simulation studies of phytoconstituents of Cymbopogon citratus (DC.). Medinformatics 2024, 1, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, V.; Lucas, A.; Patrick, C.; Mallela, K.M.G. Isothermal titration calorimetry and surface plasmon resonance methods to probe protein-protein interactions. Methods 2024, 225, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, K.; Chen, X.; Kourkoumelis, N.; Li, G.; Wang, B.; Zhu, C. Integrative analysis of genomics and transcriptome data to identify regulation networks in female osteoporosis. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 600097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | Common Name |

|---|---|

| 72 kDa type IV collagenase | MMP2 |

| Nitric oxide synthase, inducible | NOS2 |

| C5a anaphylatoxin chemotactic receptor 1 | C5AR1 |

| G-protein coupled receptor 55 | GPR55 |

| Photoreceptor-specific nuclear receptor | NR2E3 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 | CDK1 |

| Sex hormone-binding globulin | SHBG |

| Presequence protease, mitochondrial | PREP |

| Cholinesterase | BCHE |

| Prothrombin | THRB |

| Description | Number of Genes | Pathway Genes | Fold Enrichment | Enrichment FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO biological process | ||||

| GO:0006954 inflammatory response | 52 | 892 | 9.9 | 2.84 × 10−35 |

| GO:0071417 cellular response to organonitrogen compound | 38 | 654 | 9.8 | 7.22 × 10−25 |

| GO:0009725 response to hormone | 47 | 898 | 8.9 | 1.87 × 10−29 |

| GO:0010243 response to organonitrogen compound | 54 | 1061 | 8.6 | 7.26 × 10−34 |

| GO:0014070 response to organic cyclic compound | 47 | 958 | 8.3 | 3.11 × 10−28 |

| GO:1901701 cellular response to oxygen-containing compound | 59 | 1272 | 7.9 | 2.83 × 10−35 |

| GO:1901698 response to nitrogen compound | 54 | 1172 | 7.8 | 9.74 × 10−32 |

| GO:0033993 response to lipid | 44 | 980 | 7.6 | 1.02 × 10−24 |

| GO:1901700 response to oxygen-containing compound | 75 | 1752 | 7.3 | 2.97 × 10−44 |

| GO:0071495 cellular response to endogenous stimulus | 58 | 1409 | 7.0 | 7.16 × 10−32 |

| GO:0009719 response to endogenous stimulus | 68 | 1660 | 6.9 | 2.11 × 10−38 |

| GO:0042592 homeostatic proc. | 59 | 1916 | 5.2 | 6.45 × 10−26 |

| GO:0010033 response to organic substance | 92 | 3269 | 4.8 | 5.49 × 10−43 |

| GO:0070887 cellular response to chemical stimulus | 92 | 3300 | 4.7 | 9.29 × 10−43 |

| GO:0071310 cellular response to organic substance | 72 | 2609 | 4.7 | 2.96 × 10−30 |

| GO:0051239 reg. of multicellular organismal proc. | 71 | 3024 | 4.0 | 2.08 × 10−25 |

| GO:0009605 response to external stimulus | 71 | 3073 | 3.9 | 5.33 × 10−25 |

| GO:0065008 reg. of biological quality | 94 | 4103 | 3.9 | 6.38 × 10−37 |

| GO:0042221 response to chemical | 106 | 4821 | 3.7 | 5.49 × 10−43 |

| GO:0006950 response to stress | 85 | 4424 | 3.3 | 3.24 × 10−26 |

| GO cellular component | ||||

| GO:0008305 integrin complex | 5 | 31 | 27.3 | 3.86 × 10−5 |

| GO:0098636 protein complex involved in cell adhesion | 5 | 53 | 16.0 | 2.94 × 10−4 |

| GO:0043235 receptor complex | 16 | 429 | 6.3 | 6.85 × 10−7 |

| GO:0009897 external side of plasma membrane | 13 | 459 | 4.8 | 1.10 × 10−4 |

| GO:0005667 transcription regulator complex | 15 | 553 | 4.6 | 3.86 × 10−5 |

| GO:0043025 neuronal cell body | 13 | 513 | 4.3 | 2.73 × 10−4 |

| GO:0098552 side of membrane | 19 | 757 | 4.3 | 8.23 × 10−6 |

| GO:0005887 integral component of plasma membrane | 37 | 1894 | 3.3 | 8.32 × 10−9 |

| GO:0031226 intrinsic component of plasma membrane | 38 | 1978 | 3.3 | 8.32 × 10−9 |

| GO:0009986 cell surface | 19 | 1050 | 3.1 | 3.00 × 10−4 |

| GO:0042175 nuclear outer membrane–endoplasmic reticulum membrane network | 23 | 1373 | 2.8 | 1.47 × 10−4 |

| GO:0000785 chromatin | 23 | 1392 | 2.8 | 1.71 × 10−4 |

| GO:0005789 endoplasmic reticulum membrane | 22 | 1351 | 2.8 | 3.00 × 10−4 |

| GO:0098827 endoplasmic reticulum subcompartment | 22 | 1355 | 2.8 | 3.00 × 10−4 |

| GO:0005783 endoplasmic reticulum | 36 | 2262 | 2.7 | 2.06 × 10−6 |

| GO:0005694 chromosome | 29 | 2003 | 2.5 | 1.40 × 10−4 |

| GO:0031090 organelle membrane | 49 | 4154 | 2.0 | 2.57 × 10−5 |

| GO:0005654 nucleoplasm | 52 | 4581 | 1.9 | 2.57 × 10−5 |

| GO:0031982 vesicle | 50 | 4466 | 1.9 | 5.43 × 10−5 |

| GO:0031981 nuclear lumen | 55 | 4973 | 1.9 | 2.57 × 10−5 |

| GO molecular function | ||||

| GO:0004955 prostaglandin receptor activity | 8 | 10 | 135.6 | 5.70 × 10−15 |

| GO:0004954 prostanoid receptor activity | 8 | 11 | 123.3 | 1.62 × 10−14 |

| GO:0004953 icosanoid receptor activity | 9 | 17 | 89.7 | 1.45 × 10−14 |

| GO:0004879 nuclear receptor activity | 18 | 57 | 53.5 | 2.23 × 10−24 |

| GO:0098531 ligand-activated transcription factor activity | 18 | 57 | 53.5 | 2.23 × 10−24 |

| GO:0003707 nuclear steroid receptor activity | 8 | 30 | 45.2 | 3.85 × 10−10 |

| GO:0001223 transcription coactivator binding | 9 | 42 | 36.3 | 1.71 × 10−10 |

| GO:0005496 steroid binding | 17 | 107 | 26.9 | 1.01 × 10−17 |

| GO:0042562 hormone binding | 10 | 93 | 18.2 | 8.62 × 10−9 |

| GO:0001221 transcription coregulator binding | 12 | 120 | 16.9 | 3.85 × 10−10 |

| GO:0008289 lipid binding | 32 | 841 | 6.4 | 2.45 × 10−15 |

| GO:0033218 amide binding | 17 | 481 | 6.0 | 1.44 × 10−7 |

| GO:0008134 transcription factor binding | 21 | 639 | 5.6 | 8.35 × 10−9 |

| GO:0008270 zinc ion binding | 26 | 947 | 4.7 | 2.62 × 10−9 |

| GO:0038023 signaling receptor activity | 52 | 1908 | 4.6 | 6.64 × 10−20 |

| GO:0060089 molecular transducer activity | 52 | 1908 | 4.6 | 6.64 × 10−20 |

| GO:0046914 transition metal ion binding | 33 | 1247 | 4.5 | 1.47 × 10−11 |

| GO:0019899 enzyme binding | 40 | 2237 | 3.0 | 4.12 × 10−9 |

| GO:0046872 metal ion binding | 59 | 4647 | 2.2 | 2.40 × 10−8 |

| GO:0043169 cation binding | 60 | 4737 | 2.1 | 1.77 × 10−8 |

| KEGG | ||||

| Path:hsa05235 PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer | 11 | 89 | 20.9 | 2.99 × 10−10 |

| Path:hsa03320 PPAR signaling pathway | 9 | 75 | 20.3 | 1.12 × 10−8 |

| Path:hsa05215 Prostate cancer | 11 | 97 | 19.2 | 6.27 × 10−10 |

| Path:hsa04931 Insulin resistance | 11 | 108 | 17.3 | 1.47 × 10−9 |

| Path:hsa05222 Small-cell lung cancer | 9 | 92 | 16.6 | 5.13 × 10−8 |

| Path:hsa04659 Th17 cell differentiation | 10 | 108 | 15.7 | 1.50 × 10−8 |

| Path:hsa04933 AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | 9 | 100 | 15.3 | 1.02 × 10−7 |

| Path:hsa04919 Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | 10 | 121 | 14.0 | 4.02 × 10−8 |

| Path:hsa05418 Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis | 10 | 138 | 12.3 | 1.16 × 10−7 |

| Path:hsa05163 Human cytomegalovirus infection | 16 | 224 | 12.1 | 3.80 × 10−11 |

| Path:hsa04613 Neutrophil extracellular trap formation | 13 | 189 | 11.7 | 2.85 × 10−9 |

| Path:hsa05206 MicroRNAs in cancer | 11 | 161 | 11.6 | 4.48 × 10−8 |

| Path:hsa05207 Chemical carcinogenesis-receptor activation | 13 | 197 | 11.2 | 4.07 × 10−9 |

| Path:hsa05205 Proteoglycans in cancer | 13 | 202 | 10.9 | 5.05 × 10−9 |

| Path:hsa05417 Lipid and atherosclerosis | 13 | 214 | 10.3 | 9.45 × 10−9 |

| Path:hsa05171 Coronavirus disease-COVID-19 | 14 | 232 | 10.2 | 2.85 × 10−9 |

| Path:hsa05200 Pathways in cancer | 31 | 530 | 9.9 | 7.08 × 10−20 |

| Path:hsa04080 Neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction | 19 | 362 | 8.9 | 3.80 × 10−11 |

| Path:hsa04151 PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 17 | 354 | 8.1 | 1.42 × 10−9 |

| Path:hsa05165 Human papillomavirus infection | 15 | 331 | 7.7 | 1.93 × 10−8 |

| Proteins | PDB ID | Asiatic Acid | Native Ligands | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGdocking (kcal/mol) | Ki (μM) | ΔGdocking (kcal/mol) | Ki (μM) | ||

| IL-6 | 1ALU | −8.64 | 0.46 | −9.10 | 0.21 |

| STAT3 | 6NJS | −6.17 | 30.19 | −5.94 | 44.43 |

| PPARγ | 9CK0 | −7.16 | 5.65 | −5.78 | 57.93 |

| NF-κB p105 | 8TQD | −7.70 | 2.28 | −7.42 | 3.66 |

| COX-2 | 5F1A | −6.86 | 9.35 | −7.57 | 2.85 |

| ESRα | 4XI3 | −5.98 | 41.60 | −5.60 | 79.15 |

| TLR4 | 3FXI | −5.87 | 50.2 | −5.11 | 179.47 |

| HSP90-β | 5UC4 | −5.57 | 83.30 | −5.81 | 55.00 |

| PPARα | 1K7L | −6.41 | 20.13 | −6.70 | 12.33 |

| NF-κB p65 | 1NFI | −6.15 | 30.95 | −5.70 | 65.81 |

| Protein | Interaction | Residue | Distance (Å) | Same Amino Acid Residue with Native Ligand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Hydrogen bond | ASN61, GLU172, LEU62, LYS66 | 1.86, 1.71/2.32, 1.87, 3.48 | GLU172, LYS66 |

| Hydrophobic | ARG168 | 3.79 | ARG168 | |

| STAT3 | Hydrogen bond | THR346, PRO330 | 2.81, 1.96 | - |

| Hydrophobic | PRO336 | 1.96 | - | |

| PPARγ | Hydrogen bond | LYS474, TYR477, GLN451, ASP475 | 1.73, 3.07, 2.81/2.54, 1.98 | - |

| NF-κB p105 | Hydrogen bond | LYS51, LYS79, GLY68, SER74, TYR81 | 1.82, 3.03/2.92, 1.75, 2.07, 3.60 | - |

| COX-2 | Hydrogen bond | LYS79, PRO84 | 2.12, 3.77 | - |

| ESRα | Hydrogen bond | GLN500, LEU495 | 2.41, 2.03/2.25 | - |

| TLR4 | Hydrogen bond | SER534, LYS560, LYS561, GLN510 | 2.48, 2.39, 2.20, 1.88 | - |

| Hydrophobic | LEU511 | 3.73 | - | |

| Hsp90-β | Hydrogen bond | GLN23, PHE32 | 2.05, 2.42 | GLN23 |

| PPARα | Hydrogen bond | LYS208, GLN461, HIS274 | 2.09, 2.10, 3.22 | - |

| Hydrophobic | HIS274 | 3.89 | - | |

| NF-κB p65 | Hydrogen bond | ARG158, LEU179, GLN247, HIS181 | 3.06/1.71, 2.08/2.09, 1.93, 3.48 | - |

| Hydrophobic | PRO182 | 4.00 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chulrik, W.; Tedasen, A.; Kooltheat, N.; Kimseng, R.; Duangchan, T. In Silico Investigation Reveals IL-6 as a Key Target of Asiatic Acid in Osteoporosis: Insights from Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Med. Sci. 2026, 14, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010041

Chulrik W, Tedasen A, Kooltheat N, Kimseng R, Duangchan T. In Silico Investigation Reveals IL-6 as a Key Target of Asiatic Acid in Osteoporosis: Insights from Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Medical Sciences. 2026; 14(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleChulrik, Wanatsanan, Aman Tedasen, Nateelak Kooltheat, Rungruedee Kimseng, and Thitinat Duangchan. 2026. "In Silico Investigation Reveals IL-6 as a Key Target of Asiatic Acid in Osteoporosis: Insights from Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation" Medical Sciences 14, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010041

APA StyleChulrik, W., Tedasen, A., Kooltheat, N., Kimseng, R., & Duangchan, T. (2026). In Silico Investigation Reveals IL-6 as a Key Target of Asiatic Acid in Osteoporosis: Insights from Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Medical Sciences, 14(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010041