From Glucose Transport to Microbial Modulation: The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors on the Gut Microbiota

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Gut Microbiota and Metabolites

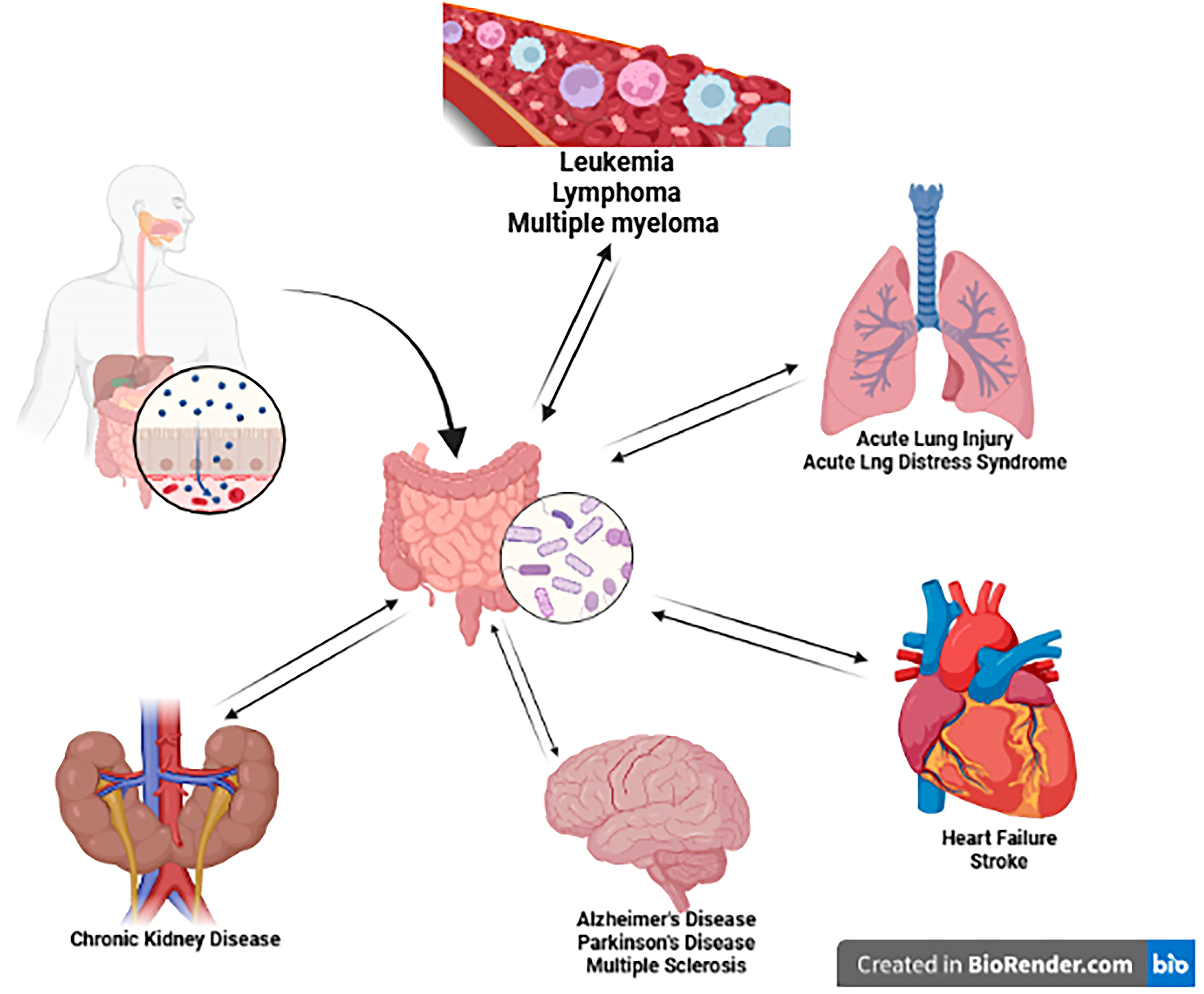

4. Bidirectional Connection of the Gut

4.1. Gut–Lung Axis

4.2. Gut–Kidney Axis

4.3. Gut–Heart Axis

4.4. Gut–Brain Axis

4.5. Gut–Hematopoietic Axis

5. Interplay Between SGLT-2 Inhibitors and Gut Microbiome

5.1. Dapagliflozin

5.2. Canagliflozin

5.3. Empagliflozin

5.4. Sotagliflozin

6. Conclusions

7. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, L.; Qu, Q.; Aydin, D.; Panova, O.; Robertson, M.J.; Xu, Y.; Dror, R.O.; Skiniotis, G.; Feng, L. Structure and mechanism of the SGLT family of glucose transporters. Nature 2022, 601, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afsar, B.; Afsar, R.E.; Lentine, K.L. The impact of sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors on gut microbiota: A scoping review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2024, 23, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, R.P.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Chouthe, R.S.; Pathan, S.K.; Une, H.D.; Reddy, G.B.; Diwan, P.V.; Ansari, S.A.; Sangshetti, J.N. SGLT inhibitors as antidiabetic agents: A comprehensive review. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 1733–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidori, D.; Sha, S.; Mudaliar, S.; Ciaraldi, T.P.; Ghosh, A.; Vaccaro, N.; Farrell, K.; Rothenberg, P.; Henry, R.R. Canagliflozin lowers postprandial glucose and insulin by delaying intestinal glucose absorption in addition to increasing urinary glucose excretion: Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 2154–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabour, M.S.; George, M.Y.; Daniel, M.R.; Blaes, A.H.; Zordoky, B.N. The Cardioprotective and Anticancer Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol 2024, 6, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabour, M.S.; George, M.Y.; Grant, M.K.O.; Zordoky, B.N. Canagliflozin differentially modulates carfilzomib-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in multiple myeloma and endothelial cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.Y.; Dabour, M.S.; Rashad, E.; Zordoky, B.N. Empagliflozin Alleviates Carfilzomib-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Mice by Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Response, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, and Autophagy. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.N.; Tadros, M.G.; George, M.Y. Empagliflozin repurposing in Parkinson’s disease; modulation of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, AMPK/SIRT-1/PGC-1alpha, and wnt/beta-catenin pathways. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarello, K.; Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska, A.; Czarzasta, K. Communication of gut microbiota and brain via immune and neuroendocrine signaling. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1118529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, N.K.; El-Naga, R.N.; Ayoub, I.M.; George, M.Y. Neuromodulatory effect of troxerutin against doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide-induced cognitive impairment in rats: Potential crosstalk between gut-brain and NLRP3 inflammasome axes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 149, 114216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.Y.; Gamal, N.K.; Mansour, D.E.; Famurewa, A.C.; Bose, D.; Messiha, P.A.; Cerchione, C. The Gut Microbiome Role in Multiple Myeloma: Emerging Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Hematol. Rep. 2025, 17, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini, E.; Ianiro, G.; Attili, F.; Bassanelli, C.; De Santis, A.; Gasbarrini, A. The human gut microbiota and virome: Potential therapeutic implications. Dig. Liver Dis. 2015, 47, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrien, M.; Belzer, C.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila and its role in regulating host functions. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 106, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Round, J.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duboc, H.; Rajca, S.; Rainteau, D.; Benarous, D.; Maubert, M.A.; Quervain, E.; Thomas, G.; Barbu, V.; Humbert, L.; Despras, G.; et al. Connecting dysbiosis, bile-acid dysmetabolism and gut inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 2013, 62, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, S.; Asha; Sharma, K.K. Gut-organ axis: A microbial outreach and networking. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 72, 636–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhawary, E.A.; George, M.Y.; Sabry, N.C.; Ayoub, I.M.; Nasr, M.; Youssef, F.S. Tectona grandis Metabolites Alleviate Oxaliplatin-induced Chemofog in Rats: Modulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Axis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 353, 120392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzi, S.F.; Michel, H.E.; Menze, E.T.; Tadros, M.G.; George, M.Y. Clotrimazole ameliorates chronic mild stress-induced depressive-like behavior in rats; crosstalk between the HPA, NLRP3 inflammasome, and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 127, 111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, C.N.; Ali, A.E.; Anber, N.H.; George, M.Y. Lactoferrin ameliorates carfilzomib-induced renal and pulmonary deficits: Insights to the inflammasome NLRP3/NF-kappaB and PI3K/Akt/GSK-3beta/MAPK axes. Life Sci. 2023, 335, 122245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Abo Elseoud, O.G.; Mohamedy, M.H.; Amer, M.M.; Mohamed, Y.Y.; Elmansy, S.A.; Kadry, M.M.; Attia, A.A.; Fanous, R.A.; Kamel, M.S.; et al. Nose-to-brain delivery of chrysin transfersomal and composite vesicles in doxorubicin-induced cognitive impairment in rats: Insights on formulation, oxidative stress and TLR4/NF-kB/NLRP3 pathways. Neuropharmacology 2021, 197, 108738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, N.; Menze, E.T.; Elsherbiny, D.A.; Tadros, M.G.; George, M.Y. Lycopene mitigates paclitaxel-induced cognitive impairment in mice; Insights into Nrf2/HO-1, NF-kappaB/NLRP3, and GRP-78/ATF-6 axes. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 137, 111262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilg, H.; Zmora, N.; Adolph, T.E.; Elinav, E. The intestinal microbiota fuelling metabolic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Backhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qin, Z.; Huang, C.; Liang, B.; Zhang, X.; Sun, W. The gut microbiota modulates airway inflammation in allergic asthma through the gut-lung axis related immune modulation: A review. Biomol. Biomed. 2025, 25, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Fu, Y.; Han, Y.; Sun, Q.; Xu, J.; Yang, Y.; Rong, R. The lung-gut crosstalk in respiratory and inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1218565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, X. Role of gut microbes in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2440125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, K.; Uchida, N.; Nakanoh, H.; Fukushima, K.; Haraguchi, S.; Kitamura, S.; Wada, J. The Gut-Kidney Axis in Chronic Kidney Diseases. Diagnostics 2024, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaimez-Alvarado, S.; Lopez, T., II; Barragan-De Los Santos, J.; Bello-Vega, D.C.; Gomez, F.J.R.; Amedei, A.; Berrios-Barcenas, E.A.; Aguirre-Garcia, M.M. Gut-Heart Axis: Microbiome Involvement in Restrictive Cardiomyopathies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A.; Nance, K.; Chen, S. The Gut-Brain Axis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutsch, A.; Kantsjo, J.B.; Ronchi, F. The Gut-Brain Axis: How Microbiota and Host Inflammasome Influence Brain Physiology and Pathology. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 604179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Sanchez, J.; Maknojia, A.A.; King, K.Y. Blood and guts: How the intestinal microbiome shapes hematopoiesis and treatment of hematologic disease. Blood 2024, 143, 1689–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, T.; Cheng, H.; Qian, P. Gut microbiota plays pivotal roles in benign and malignant hematopoiesis. Blood Sci. 2024, 6, e00200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zou, Y.; Ruan, M.; Chang, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Patients Exhibit Distinctive Alterations in the Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 558799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Jiang, H.; Cai, C.; Li, G.; Yu, G. Canagliflozin Prevents Lipid Accumulation, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Mice With Diabetic Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 839640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, C.S.; Peters, B.A.; Li, H.; Raphael, B.; Moskovits, T.; Hymes, K.; Schluter, J.; Chen, J.; Bennani, N.N.; Witzig, T.E.; et al. Microbial dysbiosis is associated with aggressive histology and adverse clinical outcome in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Hu, G.; Li, M.W.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. Gut microbiota as non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Gut 2023, 72, 1999–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, X.; Li, H.; Borger, D.K.; Wei, Q.; Yang, E.; Xu, C.; Pinho, S.; Frenette, P.S. The microbiota regulates hematopoietic stem cell fate decisions by controlling iron availability in bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 232–247.e237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, N.; Liu, X.; Zhong, X.; Jia, S.; Hua, N.; Zhang, L.; Mo, G. Dapagliflozin-affected endothelial dysfunction and altered gut microbiota in mice with heart failure. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Shi, F.H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M.C.; Feng, R.L.; Qian, C.; Liu, W.; Ma, J. Dapagliflozin Modulates the Fecal Microbiota in a Type 2 Diabetic Rat Model. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Cao, Y.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Xi, Y.; Luo, Z.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Dapagliflozin ameliorates diabetes-induced spermatogenic dysfunction by modulating the adenosine metabolism along the gut microbiota-testis axis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, W. Effect of dapagliflozin on ferroptosis through the gut microbiota metabolite TMAO during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in diabetes mellitus rats. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishima, E.; Fukuda, S.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Saigusa, D.; Mukawa, C.; Asaji, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Tsukamoto, H.; Tachikawa, T.; Tsukimi, T.; et al. Canagliflozin reduces plasma uremic toxins and alters the intestinal microbiota composition in a chronic kidney disease mouse model. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2018, 315, F824–F833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zuo, Q.; Ma, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhai, J.; Guo, Y. Canagliflozin attenuates kidney injury, gut-derived toxins, and gut microbiota imbalance in high-salt diet-fed Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2300314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Ma, J.; Wei, T.; Wang, H.; Yang, G.; Han, C.; Zhu, T.; Tian, H.; Zhang, M. The effect of canagliflozin on gut microbiota and metabolites in type 2 diabetic mice. Genes Genom. 2024, 46, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, L.; Tan, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Luo, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, N.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Empagliflozin alleviates neuroinflammation by inhibiting astrocyte activation in the brain and regulating gut microbiota of high-fat diet mice. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 360, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Zhu, T.; Cui, T.J.; Liu, Y.; Hocher, J.G.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.M.; Cai, K.W.; Deng, Z.Y.; Wang, X.H.; et al. Renoprotective effects of empagliflozin in high-fat diet-induced obesity-related glomerulopathy by regulation of gut-kidney axis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2024, 327, C994–C1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.Q.; Wang, C.H.; Cheng, P.; Fu, L.Y.; Wu, Q.J.; Cheng, G.; Guan, L.; Sun, Z.J. Effects of Empagliflozin on Gut Microbiota in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction: The Design of a Pragmatic Randomized, Open-Label Controlled Trial (EMPAGUM). Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2023, 17, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Yang, Y.; Xu, G. Empagliflozin ameliorates type 2 diabetes mellitus-related diabetic nephropathy via altering the gut microbiota. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2022, 1867, 159234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, C.; Wang, T.; Feng, L.; Peng, C.; Long, Y.; Dai, G.; Chang, L.; Wei, Y.; et al. Sotagliflozin attenuates cardiac dysfunction and depression-like behaviors in mice with myocardial infarction through the gut-heart-brain axis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 199, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug | Dosing | Species | Main Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dapagliflozin | 1 mg/kg/day, i.p., 8 weeks | Mice | ↓ Cardiac fibrosis. ↑ Endothelial function. ↓ Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. | [38] |

| Dapagliflozin | 1 mg/kg/day, oral, 4 weeks | Rats | Enriched Proteobacteria (especially Desulfovibrionaceae); no increase in beneficial bacteria (Lactobacillaceae, Bifidobacteriaceae). Dominant enterotype: Ruminococcaceae; reduced Actinobacteria and Spirochaetes. ↑ Glucose tolerance (↓ fasting/postprandial glucose, ↓ HOMA-IR) | [39] |

| Dapagliflozin | 1 mg/kg, oral, 5 weeks | Mice | ↑ Sperm quality (concentration/motility). ↓ Apoptosis/oxidative stress. Modulation of gut microbiota–testis axis. | [40] |

| Dapagliflozin | 30 μM (in vitro) | GC-2 cells | ↓ Palmitic-acid-induced apoptosis. ↓ ROS. Effects were reversed by 2′-deoxyinosine. | [40] |

| Dapagliflozin | 40 mg/kg/day, i.p., 7 days | Rats | ↓ TMAO levels in heart tissue. Modulation of gut microbiota (↑ Bacteroidetes, ↓ Firmicutes). Regulation of ferroptosis-related genes (↑ ALB, HMOX1, PPARG, CBS, LCN2, PPARA; ↓ MAPK1, MAPK8, PARP1, SRC, DPP4). Molecular docking showed strong binding between TMAO and DPP4 (docking score: −5.44). | [41] |

| Canagliflozin | 10 mg/kg, oral, 2 weeks | Mice | ↓ Plasma uremic toxins (PCS, IS). ↑ Cecal SCFAs. Modulation of gut microbiota (↓ Bifidobacterium, ↑ Actinobacteria, TM7 phyla). | [42] |

| Canagliflozin | 50 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, 6 weeks | Mice (with diabetic CVD induced by high-fat diet) | ↓ Serum lipid accumulation. ↓ Circulating inflammation markers. ↑ Cardiac mitochondrial homeostasis. ↓ Oxidative stress. ↓ Myocardial injury. Modulation of colonic microbiota composition (↑ Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio). | [34] |

| Canagliflozin | 20 mg/kg/d, oral, 12 weeks | Dahl salt-sensitive (DSS) rats | ↓ Salt-sensitive hypertension. ↓ Renal damage. ↓ Oxidative stress. Modulation of intestinal flora (↑ Corynebacterium, ↑ Bifidobacterium, ↑ Facklamia, ↑ Lactobacillus, ↑ Ruminococcus, ↑ Blautia, ↑ Coprococcus, ↑ Allobaculum spp.). ↓ Uremic toxins (methyhistidines, creatinine, homocitrulline, indoxyl sulfate). | [43] |

| Canagliflozin | 10 mg/kg/d, oral gavage, 8 weeks | db/db mice (type 2 diabetic mice) | ↑ GLP-1 level. Modulation of gut microbiota (↑ Muribaculum, ↑ Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014, ↑ Lachnospiraceae_UCG-001). Influence on intestinal fatty acid and bile acid metabolism. ↓ UDCA and HDCA. ↑ Fatty acid metabolites in feces. | [44] |

| Empagliflozin | 2 mg/kg (low) or 6 mg/kg (high), daily for 4 weeks | Mice | ↓ Neuroinflammation and astrocyte activation in high-fat diet (HFD) mice. ↑ Gut microbiota composition (↓ Lactococcus, Ligilactobacillus). ↑ Synaptophysin expression. | [45] |

| Empagliflozin | 10 mg/kg, oral, 8 weeks | Mice | ↑ Kidney function and reduced lipid accumulation in obesity-related glomerulopathy (ORG). Modulation of gut microbiota (↓ Firmicutes, increased Akkermansia). Regulated lipid metabolism pathways (glycerophospholipid, CoA biosynthesis). | [46] |

| Empagliflozin | 10 mg/day orally for 6 months | Human patients with HFpEF | ↑ Gut microbiota diversity and SCFA levels. ↓ Inflammation and myocardial fibrosis in HFpEF. | [47] |

| Empagliflozin | 10 mg/kg/day, oral, 4 weeks | Mice | ↓ Blood glucose and UACR. Restored gut microbiota diversity ↑ SCFA-producing bacteria (Bacteroides, Odoribacter) ↓ LPS-producing bacteria (Oscillibacter). ↑ Intestinal barrier function (↑ ZO-1, ↑ Occludin). | [48] |

| Sotagliflozin | 30 mg/kg/day orally, 7 days before and 25 days after MI surgery | Mice | ↓ Cardiac dysfunction. ↓ Depression-like behaviors (TST and FST). ↓ Infarct size and fibrosis Gut microbiota modulation: ↑ Alloprevotella, Prevotellaceae UCG-001, NK3B31 group | [49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

George, M.Y.; Gamal, N.K.; Safwat, K.; Mamdouh, M.; AbdElFatah, A.; Atallah, A.; Cerchione, C. From Glucose Transport to Microbial Modulation: The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors on the Gut Microbiota. Med. Sci. 2026, 14, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010022

George MY, Gamal NK, Safwat K, Mamdouh M, AbdElFatah A, Atallah A, Cerchione C. From Glucose Transport to Microbial Modulation: The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors on the Gut Microbiota. Medical Sciences. 2026; 14(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorge, Mina Y., Nada K. Gamal, Kerolos Safwat, Mohamed Mamdouh, Ahmed AbdElFatah, Abdelrahman Atallah, and Claudio Cerchione. 2026. "From Glucose Transport to Microbial Modulation: The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors on the Gut Microbiota" Medical Sciences 14, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010022

APA StyleGeorge, M. Y., Gamal, N. K., Safwat, K., Mamdouh, M., AbdElFatah, A., Atallah, A., & Cerchione, C. (2026). From Glucose Transport to Microbial Modulation: The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors on the Gut Microbiota. Medical Sciences, 14(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010022