Epidemiological and Clinical Changes in Pediatric Acute Mastoiditis Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Eight-Year Retrospective Study from a Tertiary-Level Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

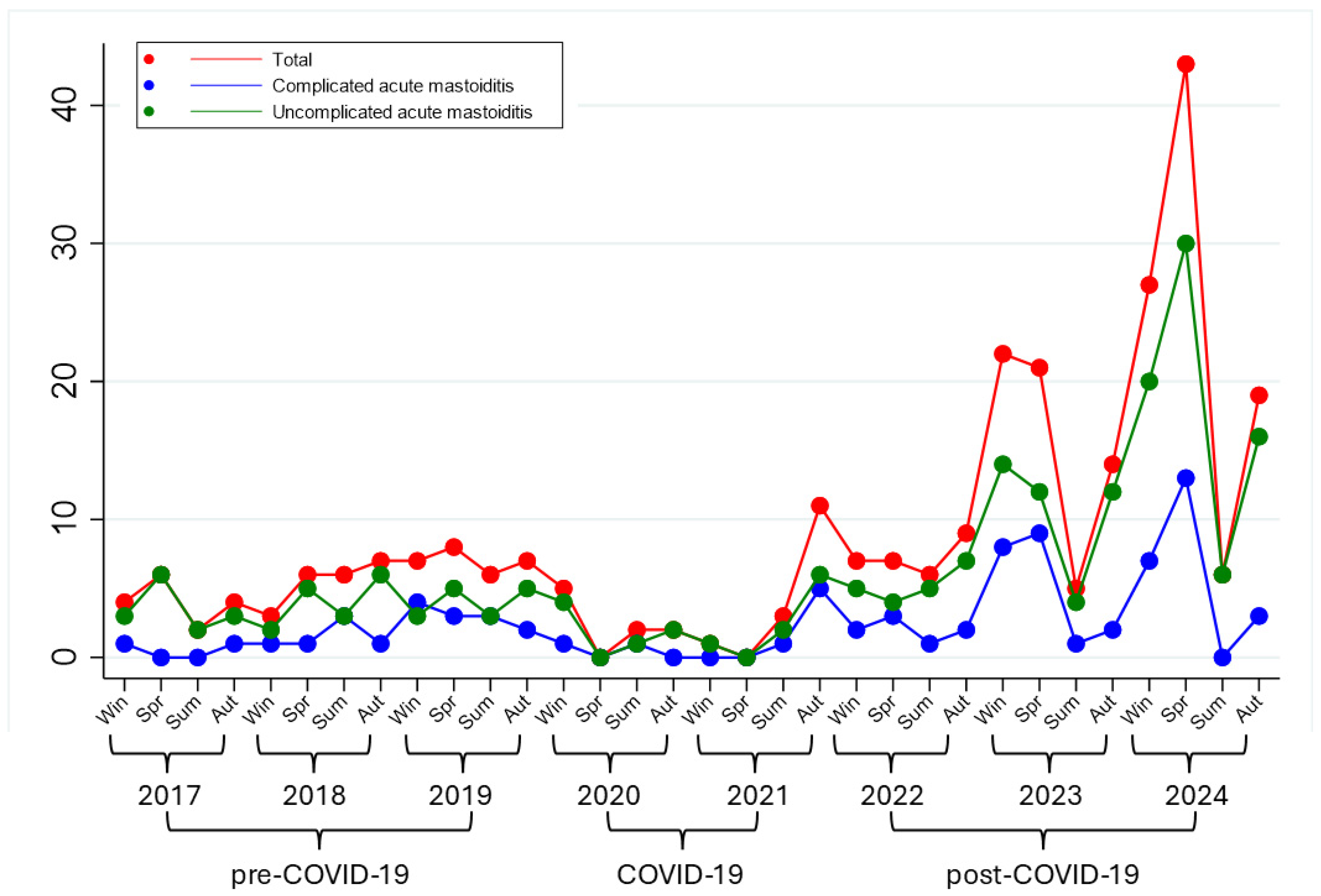

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Complications of AM

3.3. Laboratory Findings and Radiological Investigations

3.4. Surgical Management

3.5. Microbiological Data

3.6. Antibiotic and Anticoagulation Therapy

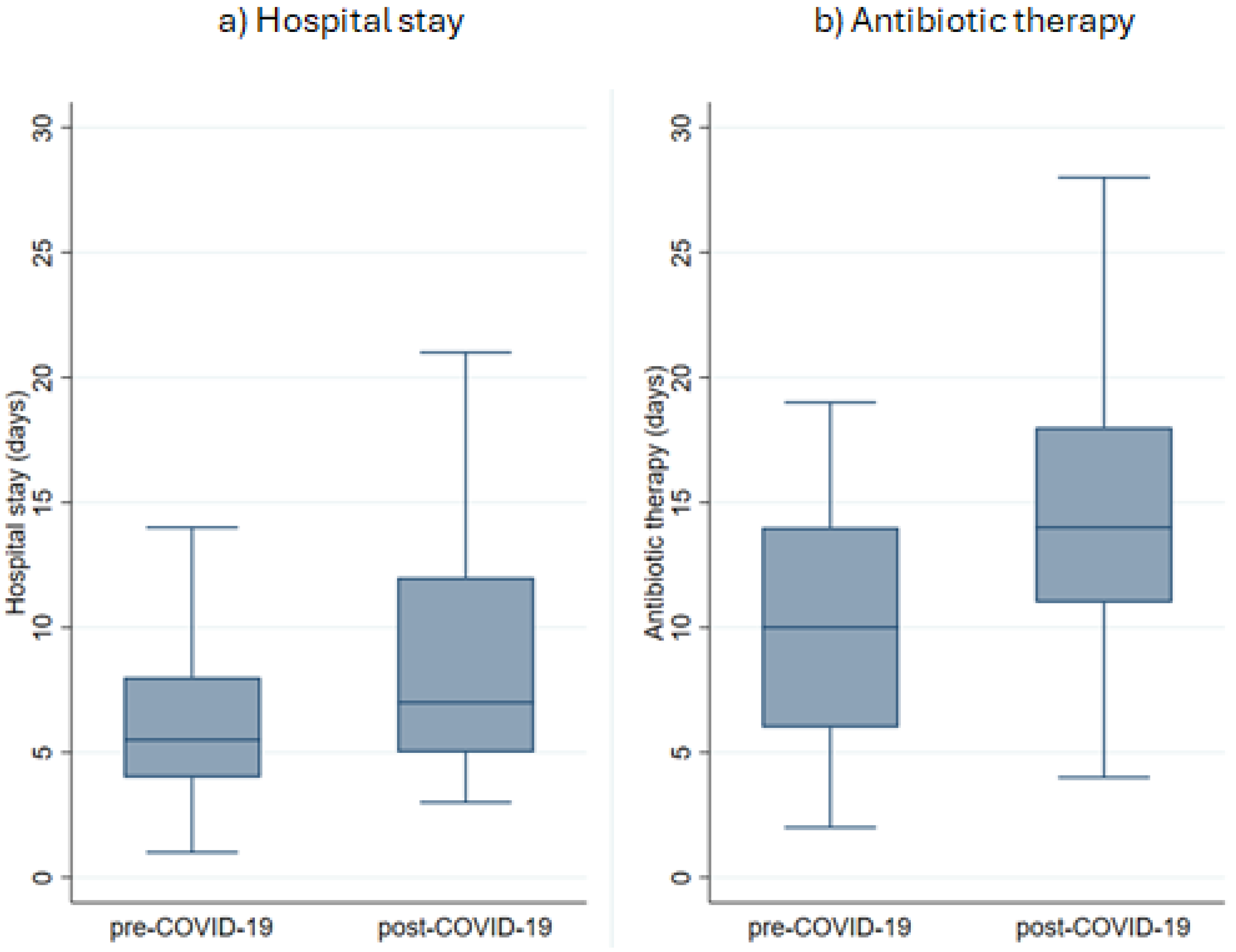

3.7. Duration of Therapy and Length of Hospitalization

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOM | acute otitis media |

| AM | acute otomastoiditis |

| CT | computed tomography |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| IV | intravenous |

| EC | extracranial complications |

| IC | intracranial complications |

| US | United States |

| NPIs | nonpharmaceutical interventions |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| PCT | Procalcitonin |

| IRR | incidence rate ratio |

| RSV | Respiratory syncytial virus |

| RT-PCR | real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Mierzwiński, J.; Tyra, J.; Haber, K.; Drela, M.; Paczkowski, D.; Puricelli, M.D.; Sinkiewicz, A. Therapeutic Approach to Pediatric Acute Mastoiditis—An Update. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 85, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L.H.Y.; Barakate, M.S.; Havas, T.E. Mastoiditis in a Pediatric Population: A Review of 11 Years Experience in Management. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73, 1520–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonsen, K.; Høstmark, K.; Hansen, S.; Andreasen, K.; Juhlin, J.; Homøe, P.; Caye-Thomasen, P. Acute Mastoiditis in Children: A 10-Year Retrospective and Validated Multicenter Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013, 32, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, P.; Ciprandi, G.; Passali, D. Acute Mastoiditis in Children. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridwell, R.E.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. High Risk and Low Prevalence Diseases: Acute Mastoiditis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 79, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, E.R. Acute Mastoiditis in Children: Treatment and Prevention—UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-mastoiditis-in-children-treatment-and-prevention/print?search=otomastoidite&topicRef=6062&source=... (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Van Den Aardweg, M.T.A.; Rovers, M.M.; De Ru, J.A.; Albers, F.W.J.; Schilder, A.G.M. A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Mastoiditis in Children. Otol. Neurotol. 2008, 29, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accorsi, E.K.; Chochua, S.; Moline, H.L.; Hall, M.; Hersh, A.L.; Shah, S.S.; Britton, A.; Hawkins, P.A.; Xing, W.; Onukwube Okaro, J.; et al. Pediatric Brain Abscesses, Epidural Empyemas, and Subdural Empyemas Associated with Streptococcus Species—United States, January 2016–August 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, P.S.; Ghosh, D.; Goldfarb, J.; Sabella, C. Lateral Sinus Thrombosis Associated with Mastoiditis and Otitis Media in Children: A Retrospective Chart Review and Review of the Literature. J. Child Neurol. 2011, 26, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, A.; Çetin, C.; Köle, M.; Avcı, H.; Akın, Y. Acute Mastoiditis in Children: A Tertiary Care Center Experience in 2015–2021. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 26, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddy, M.G.; Glazier, S.S.; Agrawal, D. Pediatric Mastoiditis in the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Era: Symptom Duration Guides Empiric Antimicrobial Therapy. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2007, 23, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parri, N.; Bettelli, S.; Storelli, F.; Caruso, R.; Pierantoni, L.; Hsu, C.-E.; Gentili, C.; Lanari, M.; Buonsenso, D. Acute Otomastoiditis in Children: A Scoping Review on Diagnosis and Antibiotic Regimens. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häußler, S.M.; Peichl, J.; Bauknecht, C.; Spierling, K.; Olze, H.; Betz, C.; Stölzel, K. A Novel Diagnostic and Treatment Algorithm for Acute Mastoiditis in Children Based on 109 Cases. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, e241–e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.; Rotenberg, B.W.; Berkowitz, R.G. The Relationship Between Acute Mastoiditis and Antibiotic Use for Acute Otitis Media in Children. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008, 134, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, M.R.; Shetty, K.; Camilon, P.R.; Shetty, A.; Levi, J.R.; Devaiah, A.K. Management of Acute Complicated Mastoiditis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2022, 41, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.; Callon, W. Mastoiditis. Pediatr. Rev. 2024, 45, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, W.S. Otitis, Sinusitis, and Mastoiditis: Ear or Facial Pain Following a Common Cold. In Introduction to Clinical Infectious Diseases; Domachowske, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 37–51. ISBN 978-3-319-91079-6. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-Alonso, A.; Roldán-Pascual, N.; Pérez-Mora, R.M.; Jiménez-Montero, B.; Cabero-Pérez, M.J.; Morales-Angulo, C. Acute Mastoiditis: 30 Years Review in a Tertiary Hospital. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 188, 112204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.-C.; Su, Y.-T.; Chen, P.-H.; Tsai, C.-C.; Lin, T.-I.; Wu, J.-R. Changing Patterns of Infectious Diseases in Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1200617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, J.; Olin, K.; Holdrege, M.C.; Hartsell, J.; Meyers, L.; Cox, C.; Powell, M.; Cook, C.V.; Jones, J.; Robbins, T.; et al. The Effects of Social Distancing Policies on Non-SARS-CoV-2 Respiratory Pathogens. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: Outbreaks of Post-Pandemic Childhood Pneumonia and the Re-Emergence of Endemic Respiratory Infections. Med. Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e943312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New Mexico Health Alert Network (HAN). Increased Respiratory Virus Activity, Especially Among Children, Early in the 2022–2023 Fall and Winter. Available online: https://www.nmhealth.org/publication/view/general/7916/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Meyer Sauteur, P.M.; Beeton, M.L.; Pereyre, S.; Bébéar, C.; Gardette, M.; Hénin, N.; Wagner, N.; Fischer, A.; Vitale, A.; Lemaire, B.; et al. Mycoplasma Pneumoniae: Delayed Re-Emergence after COVID-19 Pandemic Restrictions. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e100–e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, A.; Capello, C.; AlMubarak, Z.; Dzioba, A.; You, P.; Nashid, N.; Barton, M.; Husein, M.; Strychowsky, J.E.; Graham, M.E. Changes in Operative Otolaryngology Infections Related to the COVID19 Pandemic: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 171, 111650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuon, D.; Ogrin, S.; Engels, J.; Aldrich, A.; Olivero, R.M. Notes from the Field: Increase in Pediatric Intracranial Infections During the COVID-19 Pandemic—Eight Pediatric Hospitals, United States, March 2020–March 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1000–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimi, L.; Cinalli, G.; Frassanito, P.; Arcangeli, V.; Auer, C.; Baro, V.; Bartoli, A.; Bianchi, F.; Dietvorst, S.; Di Rocco, F.; et al. Intracranial Complications of Sinogenic and Otogenic Infections in Children: An ESPN Survey on Their Occurrence in the Pre-COVID and Post-COVID Era. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2024, 40, 1221–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman-Bruce, H.; Umana, E.; Mills, C.; Mitchell, H.; McFetridge, L.; McCleary, D.; Waterfield, T. Diagnostic Test Accuracy of Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein for Predicting Invasive and Serious Bacterial Infections in Young Febrile Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2024, 8, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Bruel, A.; Thompson, M.J.; Haj-Hassan, T.; Stevens, R.; Moll, H.; Lakhanpaul, M.; Mant, D. Diagnostic Value of Laboratory Tests in Identifying Serious Infections in Febrile Children: Systematic Review. BMJ 2011, 342, d3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, D.G.; Oski, F.A. Hematology of Infancy and Childhood, 3rd ed.; W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-072-166-658-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P.-I.; Hsueh, P.-R.; Chuang, J.-H.; Liu, M.-T. Changing Epidemic Patterns of Infectious Diseases during and after COVID-19 Pandemic in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2024, 57, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintero-Salgado, E.; Briseno-Ramírez, J.; Vega-Cornejo, G.; Damian-Negrete, R.; Rosales-Chavez, G.; De Arcos-Jiménez, J.C. Seasonal Shifts in Influenza, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and Other Respiratory Viruses After the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Eight-Year Retrospective Study in Jalisco, Mexico. Viruses 2024, 16, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoretto, M.H.; Mitre, E.I.; Vianna, M.F.; Lazarini, P.R. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Acute Otitis Media among the Pediatric Population. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 153, 111009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.; Youngkin, E.; Zipprich, J.; Bilski, K.; Gregory, C.J.; Dominguez, S.R.; Mumm, E.; McMahon, M.; Como-Sabetti, K.; Lynfield, R.; et al. Notes from the Field: Increase in Pediatric Invasive Group A Streptococcus Infections—Colorado and Minnesota, October–December 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Lansiaux, E.; Reinis, A. Group A Streptococcal (GAS) Infections among Children in Europe: Taming the Rising Tide. New Microbes New Infect. 2023, 51, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Ashman, M.; Taha, M.-K.; Varon, E.; Angoulvant, F.; Levy, C.; Rybak, A.; Ouldali, N.; Guiso, N.; Grimprel, E. Pediatric Infectious Disease Group (GPIP) Position Paper on the Immune Debt of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Childhood, How Can We Fill the Immunity Gap? Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messacar, K.; Baker, R.E.; Park, S.W.; Nguyen-Tran, H.; Cataldi, J.R.; Grenfell, B. Preparing for Uncertainty: Endemic Pediatric Viral Illnesses after COVID-19 Pandemic Disruption. Lancet 2022, 400, 1663–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shet, A.; Carr, K.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Sodha, S.V.; Prosperi, C.; Wunderlich, J.; Wonodi, C.; Reynolds, H.W.; Mirza, I.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic on Routine Immunization Services: Evidence of Disruption and Recovery from 170 Countries and Territories. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e186–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamson, E.; Forbes, C.; Wittkopf, P.; Pandey, A.; Mendes, D.; Kowalik, J.; Czudek, C.; Mugwagwa, T. Impact of Pandemics and Disruptions to Vaccination on Infectious Diseases Epidemiology Past and Present. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2219577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Haemophilus influenzae Disease—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Haemophilus%20influenzae_AER_2022_Report-final.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: Global Health Concerns as Vaccine-Preventable Infections Including SARS-CoV-2 (JN.1), Influenza, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), and Measles Continue to Rise. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e943911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draut, S.; Müller, J.; Hempel, J.-M.; Schrötzlmair, F.; Simon, F. Tenfold Increase: Acute Pediatric Mastoiditis Before, During, and After COVID-19 Restrictions. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laryea, R.; Zhang, W.; Glaun, M.; Lee, J.E.; Nguyen, J.D.; Sitton, M.S.; Lambert, E.M. Pediatric Acute Mastoiditis: A Comparison of Patients with and without Intracranial Complications. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 193, 112329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marra, L.P.; Sartori, A.L.; Martinez-Silveira, M.S.; Toscano, C.M.; Andrade, A.L. Effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccines on Otitis Media in Children: A Systematic Review. Value Health 2022, 25, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, R.; Seeman, S.; Grinnell, M.; Bulkow, L.; Kokesh, J.; Emmett, S.; Holve, S.; McCollum, J.; Hennessy, T. Trends in Otitis Media and Myringotomy with Tube Placement Among American Indian and Alaska Native Children and the US General Population of Children After Introduction of the 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, e6–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, K.O.; Ishman, S.L.; Tabangin, M.E.; Altaye, M.; Meinzen-Derr, J.; Choo, D.I. Pediatric Acute Mastoiditis in the Era of Pneumococcal Vaccination. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutouzis, E.I.; Michos, A.; Koutouzi, F.I.; Chatzichristou, P.; Parpounas, K.; Georgaki, A.; Theodoridou, M.; Tsakris, A.; Syriopoulou, V.P. Pneumococcal Mastoiditis in Children Before and After the Introduction of Conjugate Pneumococcal Vaccines. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 35, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotto, M.; Contini, P.; Ottonello, L.; Pende, A.; Dallegri, F.; Montecucco, F. Neutrophil Migration toward C 5a and CXCL 8 Is Prevented by Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs via Inhibition of Different Pathways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 3376–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronstein, B.N.; Van De Stouwe, M.; Druska, L.; Levin, R.I.; Weissmann, G. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Agents Inhibit Stimulated Neutrophil Adhesion to Endothelium: Adenosine Dependent and Independent Mechanisms. Inflammation 1994, 18, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Luis, M.; Herrera-García, A.; Arce-Franco, M.; Armas-González, E.; Rodríguez-Pardo, M.; Lorenzo-Díaz, F.; Feria, M.; Cadenas, S.; Sánchez-Madrid, F.; Díaz-González, F. Superoxide Anion Mediates the L-Selectin down-Regulation Induced by Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Human Neutrophils. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legras, A.; Giraudeau, B.; Jonville-Bera, A.-P.; Camus, C.; François, B.; Runge, I.; Kouatchet, A.; Veinstein, A.; Tayoro, J.; Villers, D.; et al. A Multicentre Case-Control Study of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs as a Risk Factor for Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit. Care 2009, 13, R43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiriot, G.; Philippot, Q.; Elabbadi, A.; Elbim, C.; Chalumeau, M.; Fartoukh, M. Risks Related to the Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adult and Pediatric Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.L. Could Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) Enhance the Progression of Bacterial Infections to Toxic Shock Syndrome? Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 21, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikaeloff, Y.; Kezouh, A.; Suissa, S. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use and the Risk of Severe Skin and Soft Tissue Complications in Patients with Varicella or Zoster Disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 65, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicollas, R.; Moreddu, E.; Le Treut-Gay, C.; Mancini, J.; Akkari, M.; Mondain, M.; Scavarda, D.; Hosanna, G.; Fayoux, P.; Pondaven-Letourmy, S.; et al. Ibuprofen as risk-factor for complications of acute anterior sinusitis in children. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2020, 137, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bourgeois, M.; Ferroni, A.; Leruez-Ville, M.; Varon, E.; Thumerelle, C.; Brémont, F.; Fayon, M.J.; Delacourt, C.; Ligier, C.; Watier, L.; et al. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug without Antibiotics for Acute Viral Infection Increases the Empyema Risk in Children: A Matched Case—Control Study. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 47–53.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodilsen, J.; D’Alessandris, Q.G.; Humphreys, H.; Iro, M.A.; Klein, M.; Last, K.; Montesinos, I.L.; Pagliano, P.; Sipahi, O.R.; San-Juan, R.; et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Guidelines on Diagnosis and Treatment of Brain Abscess in Children and Adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sarno, L.; Cammisa, I.; Curatola, A.; Pansini, V.; Eftimiadi, G.; Gatto, A.; Chiaretti, A. A Scoping Review of the Management of Acute Mastoiditis in Children: What Is the Best Approach? Turk. J. Pediatr. 2023, 65, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, B.; Sun, H.; Lyu, J.; Shao, J.; Lu, X.; Xu, J.; Yang, J.; Chi, F.; et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Virus in Middle Ear Effusions and Its Association with Otitis Media with Effusion. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moonis, G.; Mitchell, R.; Szeto, B.; Lalwani, A.K. Radiologic Assessment of the Sinonasal Tract, Nasopharynx and Mastoid Cavity in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection Presenting with Acute Neurological Symptoms. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2021, 130, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, E.; Balai, E.; Kwatra, D.; Banerjee, S.; Hoskison, E. Sinus, Middle-Ear and Mastoid Radiological Findings of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2023, 137, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaelian, A.; Won, S.-Y.; Trnovec, S.; Behmanesh, B.; Barz, S.; Busjahn, C.; Reuter, D.A.; Zhang, L.; Mlynski, R.; Freiman, T.; et al. Otogenic Brain Abscess and Concomitant Acute COVID-19 Infection: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Neurol. Surg. A Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 2025, 86, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, X.; Wu, W.; Huang, Z.; Lei, Z.; Xu, W.; Chen, D.; Wu, X.; et al. Association between the Nasopharyngeal Microbiome and Metabolome in Patients with COVID-19. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2021, 6, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolhe, R.; Sahajpal, N.S.; Vyavahare, S.; Dhanani, A.S.; Adusumilli, S.; Ananth, S.; Mondal, A.K.; Patterson, G.T.; Kumar, S.; Rojiani, A.M.; et al. Alteration in Nasopharyngeal Microbiota Profile in Aged Patients with COVID-19. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symptoms | Pre-COVID-19 No. (%) | Post-COVID-19 No. (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mastoid swelling | 50 (71.4%) | 129 (69.4%) | 0.75 |

| Headache | 8 (11.4%) | 89 (47.9%) | <0.01 |

| Fever | 38 (54.3%) | 158 (85.0%) | <0.01 |

| Vomiting | 6 (8.6%) | 40 (21.5%) | <0.05 |

| Otalgia | 55 (78.6%) | 160 (86.0%) | 0.15 |

| Seizures | 1 (1.4%) | 13 (7.0%) | 0.12 |

| Altered consciousness | 0 (0%) | 17 (9.1%) | <0.01 |

| Photophobia | 1 (1.4%) | 13 (7.0%) | 0.12 |

| Cranial nerve deficits | 8 (11.4%) | 8 (4.3%) | <0.05 |

| (a) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | Pre-COVID-19 | Post-COVID-19 | ||

| Per Year | Total No. | Per Year | Total No. | |

| Extracranial complications | 4.4 | 14 | 6.7 | 20 |

| Facial nerve palsy | 1.9 | 6 | 1.0 | 3 |

| Bezold’s abscess | 0.9 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Osteomyelitis | 1.3 | 4 | 1.0 | 3 |

| Subperiosteal abscess | 2.5 | 8 | 5.0 | 15 |

| Intracranial complications | 3.8 | 12 | 12.3 | 37 |

| Thrombosis | 2.8 | 9 | 8.7 | 26 |

| Meningitis | 0.6 | 2 | 3.0 | 9 |

| Brain abscess | 0.3 | 1 | 1.0 | 3 |

| Epidural empyema | 2.2 | 7 | 6.0 | 18 |

| Subdural empyema | 0.9 | 3 | 2.3 | 7 |

| (b) | ||||

| Complications | IRR | 95% CI | ||

| Extracranial complications | 1.51 | 0.72–3.23 | ||

| Subperiosteal abscess | 1.98 | 0.79–5.39 | ||

| Intracranial complications | 3.25 | 1.66–6.86 | ||

| Thrombosis | 3.05 | 1.38–7.39 | ||

| Meningitis | 4.75 | 0.98–45.18 | ||

| Epidural empyema | 2.71 | 1.08–7.68 | ||

| Subdural empyema | 2.46 | 0.56–14.76 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarno, M.; Pascarella, A.; De Lucia, A.; Spennato, P.; Savoia, F.; Calì, C.; Casale, A.; Dora, A.; Meccariello, G.; Borrelli, R.; et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Changes in Pediatric Acute Mastoiditis Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Eight-Year Retrospective Study from a Tertiary-Level Center. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040297

Sarno M, Pascarella A, De Lucia A, Spennato P, Savoia F, Calì C, Casale A, Dora A, Meccariello G, Borrelli R, et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Changes in Pediatric Acute Mastoiditis Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Eight-Year Retrospective Study from a Tertiary-Level Center. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(4):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040297

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarno, Marco, Antonia Pascarella, Antonietta De Lucia, Pietro Spennato, Fabio Savoia, Camilla Calì, Alida Casale, Adelia Dora, Giulia Meccariello, Raffaele Borrelli, and et al. 2025. "Epidemiological and Clinical Changes in Pediatric Acute Mastoiditis Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Eight-Year Retrospective Study from a Tertiary-Level Center" Medical Sciences 13, no. 4: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040297

APA StyleSarno, M., Pascarella, A., De Lucia, A., Spennato, P., Savoia, F., Calì, C., Casale, A., Dora, A., Meccariello, G., Borrelli, R., Nunziata, F., De Caro, S., Petrone, E., Parente, I., Esposito, A., Russo, C., Covelli, E. M., De Luca, C., Schiavulli, M., ... Cinalli, G. (2025). Epidemiological and Clinical Changes in Pediatric Acute Mastoiditis Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Eight-Year Retrospective Study from a Tertiary-Level Center. Medical Sciences, 13(4), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040297