Atrial Myxoma in Both Chambers: Biatrial or Bilateral? A Rare Case Resected via Endoscopic Approach and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

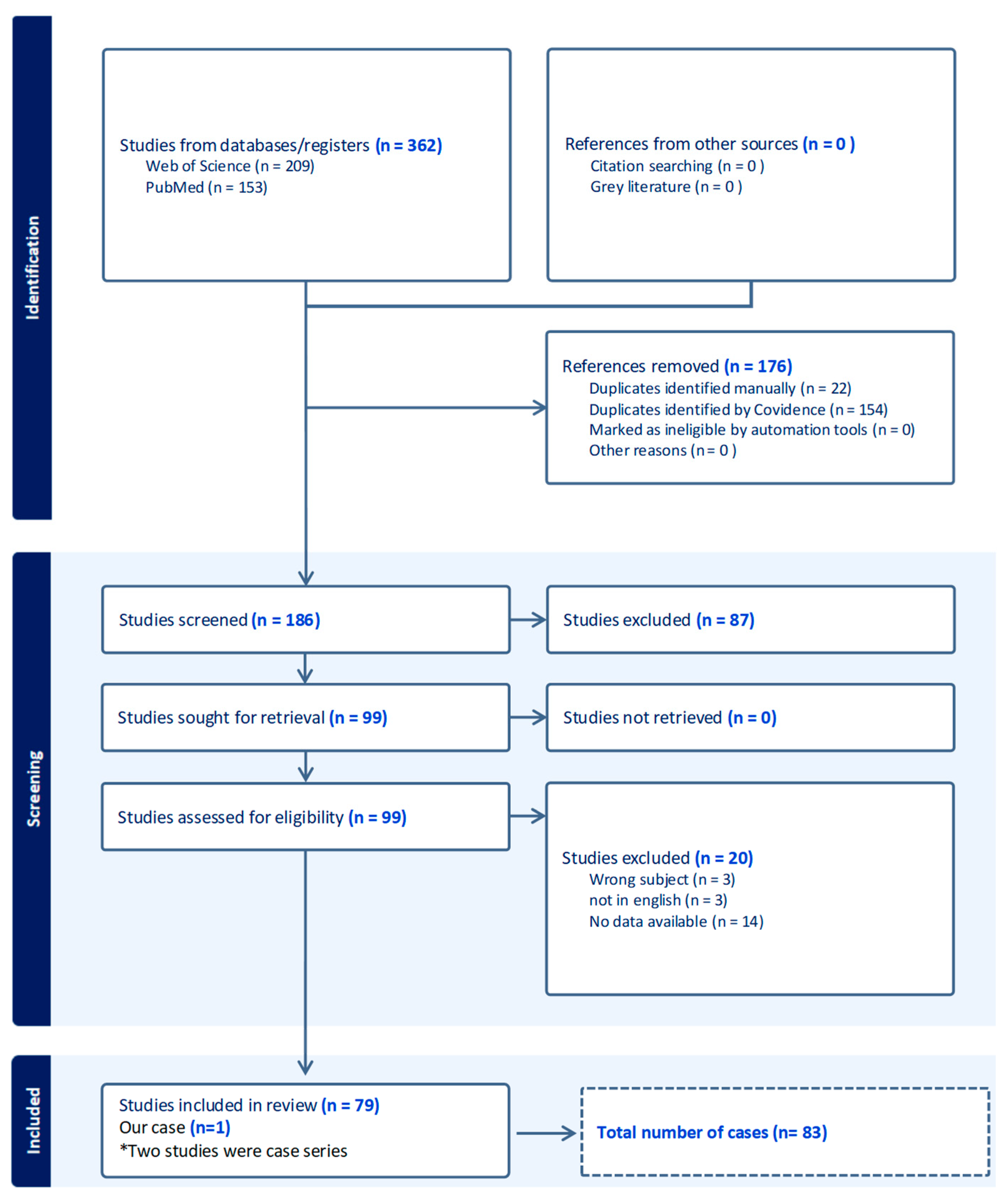

3. Materials and Methods

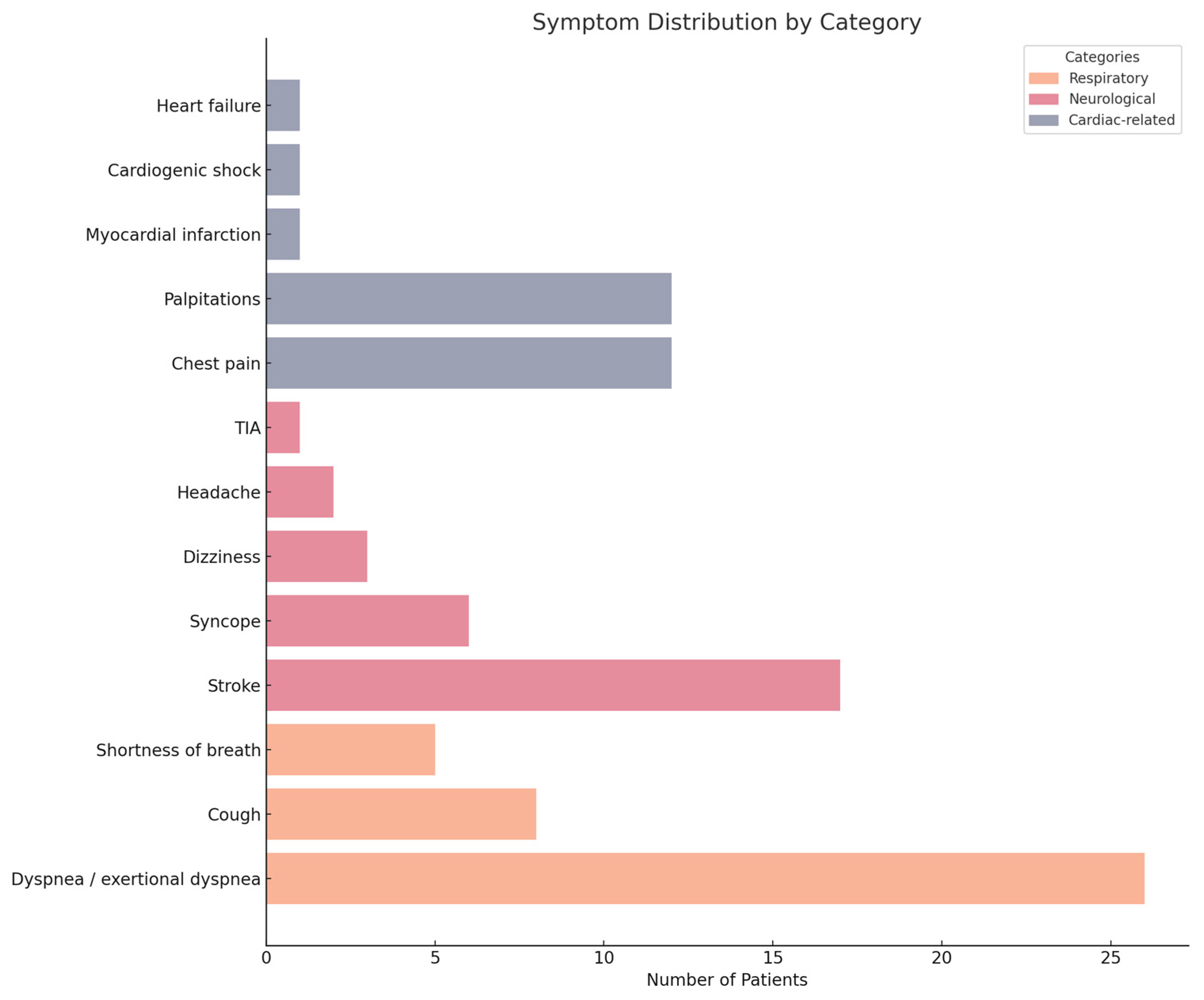

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yipintsol, T.; Donavanik, L.; Bhamarapravati, N.; Jumbala, B.; Prachaubmoh, K. Bilateral atrial myxoma with successful removal: Report of a Case. Dis. Chest 1967, 52, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azari, A.; Moravvej, Z.; Chamanian, S.; Bigdelu, L. An unusual biatrial cardiac myxoma in a young patient. Korean J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 48, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Islam, A.K.M.M. Cardiac myxomas: A narrative review. World J. Cardiol. 2022, 14, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Di Vito, A.; Mignogna, C.; Donato, G. The mysterious pathways of cardiac myxomas: A review of histogenesis, pathogenesis and pathology. Histopathology 2015, 66, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Yuhara, S.; Okawa, H.; Hasegawa, H.; Yokote, J.; Tamaki, S.; Mii, S. Giant biatrial myxoma with two different gross findings. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 66, 358–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandmougin, D.; Moussu, T.; Hubert, M.; Perin, B.; Huber, A.; Delolme, M.C.; Maureira, J.P. Recurrent Biatrial Myxomas in Carney Complex with a Spinal Melanotic Schwannoma: Advocacy for a Rigorous Multidisciplinary Follow-Up. Case Rep. Cardiol. 2023, 2023, 7896180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pitsava, G.; Zhu, C.; Sundaram, R.; Mills, J.L.; Stratakis, C.A. Predicting the risk of cardiac myxoma in Carney complex. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cao, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Y. Familial cardiac myxoma with multifocal recurrences: A case report and review of the literature. J. Biomed. Res. 2011, 25, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Min, S.Y.; Lim, Y.H.; Lee, H.T.; Shin, J.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, H. Biatrial myxoma and multiple organ infarctions combined with Leriche syndrome in a female patient. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2014, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yoon, S.J.; Park, S.C.; You, Y.P.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, M.K.; Jeong, K.T.; Lee, J.W. Multicentric biatrial myxoma in a young female patient: Case report. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dang, H.Q.; Le, H.T.; Dinh, L.N. Endoscopic port access resection of left atrial myxoma: Clinical outcomes and a single surgeon’s learning curve experience. JTCVS Tech. 2023, 23, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumary, V.S.; Madhavan, S.; Akhil, P.C.; Jayaprakash, K.; George, R. Two-time recurrence of a right atrial myxoma. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent.) 2015, 28, 507–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chitwood, W.R., Jr. Clarence Crafoord and the first successful resection of a cardiac myxoma. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1992, 54, 997–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odim, J.; Reehal, V.; Laks, H.; Mehta, U.; Fishbein, M.C. Surgical pathology of cardiac tumors. Two decades at an urban institution. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2003, 12, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitei, E.D.; Harpa, M.M.; Al Hussein, H.; Ghiragosian, C.; Stroe, V.I.; Calburean, P.; Gurzu, S.; Suciu, H. Pulmonary Valve Fibroelastoma, Still a Very Rare Cardiac Tumor: Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cilliers, A.M.; van Unen, H.; Lala, S.; Vanderdonck, K.H.; Hartman, E. Massive biatrial myxomas in a child. Pediatr. Cardiol. 1999, 20, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, H.; Chen, G.; Hu, J.; He, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T. Case Report: Biatrial Myxoma with Pulmonary Embolism and Cerebral Embolism: Clinical Experience and Literature Review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 812765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jia, X.; Kohli, A.; Jarjour, J.; Chen, C.J.; Gilmore, B.; Tabbaa, R.; Poythress, E.L. Recurrent Biatrial Myxoma in a 41-Year-Old Woman after Left Atrial Myxoma Resection. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2017, 44, 402–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krause, S.; Adler, L.N.; Reddy, P.S.; Magovern, G.J. Intracardiac myxoma in siblings. Chest 1971, 60, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takigami, M.; Kawata, M.; Kintsu, M.; Kodaira, M.; Sogabe, K.; Kato, Y.; Matsuura, T.; Kamemura, K.; Hirayama, Y.; Adachi, K.; et al. Familial Carney complex with biatrial cardiac myxoma. J. Cardiol. Cases. 2017, 15, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Stratakis Constantine, A. Carney Complex. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Bick, S., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993–2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1286/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Bandettini, W.P.; Karageorgiadis, A.S.; Sinaii, N.; Rosing, D.R.; Sachdev, V.; Schernthaner-Reiter, M.H.; Gourgari, E.; Papadakis, G.Z.; Keil, M.F.; Lyssikatos, C.; et al. Growth hormone and risk for cardiac tumors in Carney complex. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2016, 23, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinfeld, A.; Katsumata, T.; Westaby, S. Recurrent cardiac myxoma: Seeding or multifocal disease? Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1998, 66, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turhan, S.; Tulunay, C.; Altin, T.; Dincer, I. Second recurrence of familial cardiac myxomas in atypical locations. Can. J. Cardiol. 2008, 24, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Vega Adauy, J.; Gabrielli, L.; Córdova, S.; McNab, P.; Saavedra, R.; Piñeiro, M.; Zalaquett, R. “Gigantic” biatrial myxoma with right heart functional impairment. Echocardiography 2018, 35, 1060–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. Biatrial myxoma floating like a butterfly: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine 2018, 97, e9558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zamkan, B.K.; Hashem, A.M.; Alaaeldin, S.A.; Aziz, M.A. An exceptionally giant left atrial myxoma: A case report and literature review. Eur. Heart J.-Case Rep. 2020, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijan, V.; Vupputuri, A.; Chandrasekharan Nair, R. An Unusual Case of Biatrial Myxoma in a Young Female. Case Rep. Cardiol. 2016, 2016, 3545480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aydın, C.; Taşal, A.; Ay, Y.; Vatankulu, M.A.; Inan, B.; Bacaksız, A. A giant right atrial villous myxoma with simultaneous pulmonary embolism. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014, 5, 206–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laksmono, N.; Tansa, C.W.; Karina, B.I.; Anestya, N.; Agustina, H. A rare case of biatrial myxoma in an 11-year-old girl patient with thromboembolic stroke: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2025, 131, 111311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jain, G.; Minhas, H.S.; Khangrot, S.S.; Pandit, B.N. Biatrial Myxoma Twins with Acute Myocardial Infarction-A Malady of Rarities! J. Assoc. Physicians India 2025, 73, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexiou, K.; Wilbring, M.; Matschke, K. Angina pectoris as first manifestation of a huge biatrial myxoma. Acta Cardiol. 2009, 64, 667–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Chen, T. Total thoracoscopic surgery for biatrial cardiac myxoma: A case report. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Tewari, P.; Soori, R.; Agarwal, S.K. Atrial myxomas causing severe left and right ventricular dysfunction. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2017, 20, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havrankova, E.; Stenova, E.; Olejarova, I.; Sollarova, K.; Kinova, S. Carney complex with biatrial cardiac myxoma. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 20, 890–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munirathinam, G.K.; Kumar, B.; Singh, H. Role of transesophageal echocardiography in the recurrent biatrial myxoma of uncommon origin. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2022, 25, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Totsugawa, T.; Kuinose, M.; Nishigawa, K.; Tsushima, Y.; Yoshitaka, H.; Ishida, A. Intraseptal biatrial myxoma excised via the superior septal approach. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 56, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, A.R.; López-Fernández, T.; Couch, L.S.; Asteggiano, R.; Aznar, M.C.; Bergler-Klein, J.; Boriani, G.; Cardinale, D.; Cordoba, R.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4229–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutley, R.S.; Melham, N.; Skinner, H.; Richens, D. Unusual case of two synchronous intracavitary primary cardiac tumors. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008, 85, 1086–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morokuma, H.; Katayama, Y.; Kamohara, K.; Minematsu, N.; Koga, S. Extensive resection and double-patch reconstruction for left atrial myxoma. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 20, 839–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoli, G.; Muzzi, L.; Lucchese, G.; Uricchio, N.; Chiavarelli, M. Large left atrial myxoma with severe mitral regurgitation: The inverted T-shaped biatrial incision revisited. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2006, 33, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harpa, M.M.; Oltean, S.F.; Al Hussein, H.; Anitei, D.E.; Puscas, I.A.; Bănceu, C.M.; Veres, M.; Opriș, D.R.; Balau, R.A.; Suciu, H. Successful Treatment of Unilateral Pulmonary Edema as Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery Complication-Case Presentation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aboelnazar, N.S.; Loshusan, R.B.; Chu, M.W.A. Long-Term Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Endoscopic Versus Sternotomy Surgical Resection of Primary Cardiac Tumors. Innovations 2024, 19, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harpa, M.M.; Anitei, E.D.; Ghiragosian, C.; Calburean, P.; Opris, D.R.; Banceu, M.C.; Arbanasi, E.M.; Suciu, H.; Al Hussein, H. Endoscopic Mitral Surgery in Noonan Syndrome-Case Report and Considerations. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nishio, S.; Kusunose, K.; Yamada, H.; Hotchi, J.; Hayashi, S.; Bando, M.; Saijo, Y.; Hirata, Y.; Abe, M.; Sata, M. Multimodality imaging of biatrial myxomas in an asymptomatic patient. J. Cardiol. Cases 2014, 10, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stoica, A.I.; Harpa, M.M.; Banceu, C.M.; Ghiragosian, C.; Opris, C.E.; Al-Hussein, H.; Al-Hussein, H.; Flamind Oltean, S.; Mezei, T.; Mares, R.G.; et al. A Rare Case of Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Cardiac Sarcoma with Inflammatory Pattern. Medicina 2022, 58, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Flint, N.; Siegel, R.J.; Bannykh, S.; Luthringer, D.J. Bi-atrial cardiac myxoma with glandular differentiation: A case report with detailed radiologic-pathologic correlation. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2018, 2, yty045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harpa, M.M.; Anitei, E.-D.; Al Hussein, H.; Veres, M.; Gurzu, S.; Opriș, D.R.; Sorina, F.E.; Arbănași, E.M.; Ghiragosian, C.; Banceu, C.M.; et al. Atrial Myxoma in Both Chambers: Biatrial or Bilateral? A Rare Case Resected via Endoscopic Approach and Literature Review. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040294

Harpa MM, Anitei E-D, Al Hussein H, Veres M, Gurzu S, Opriș DR, Sorina FE, Arbănași EM, Ghiragosian C, Banceu CM, et al. Atrial Myxoma in Both Chambers: Biatrial or Bilateral? A Rare Case Resected via Endoscopic Approach and Literature Review. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(4):294. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040294

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarpa, Marius Mihai, Emanuel-David Anitei, Hussam Al Hussein, Mihaly Veres, Simona Gurzu, Diana Roxana Opriș, Fiat Emilia Sorina, Emil Marian Arbănași, Claudiu Ghiragosian, Cosmin Marian Banceu, and et al. 2025. "Atrial Myxoma in Both Chambers: Biatrial or Bilateral? A Rare Case Resected via Endoscopic Approach and Literature Review" Medical Sciences 13, no. 4: 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040294

APA StyleHarpa, M. M., Anitei, E.-D., Al Hussein, H., Veres, M., Gurzu, S., Opriș, D. R., Sorina, F. E., Arbănași, E. M., Ghiragosian, C., Banceu, C. M., Suciu, H., & Balan, R. (2025). Atrial Myxoma in Both Chambers: Biatrial or Bilateral? A Rare Case Resected via Endoscopic Approach and Literature Review. Medical Sciences, 13(4), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040294