Assessing Quality of Life in Genital Lichen Sclerosus: The Role of Disease Severity and Localization—A Swedish Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Primary Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Dermatology Life Quality Index

2.4. Lichen Sclerosus Score

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

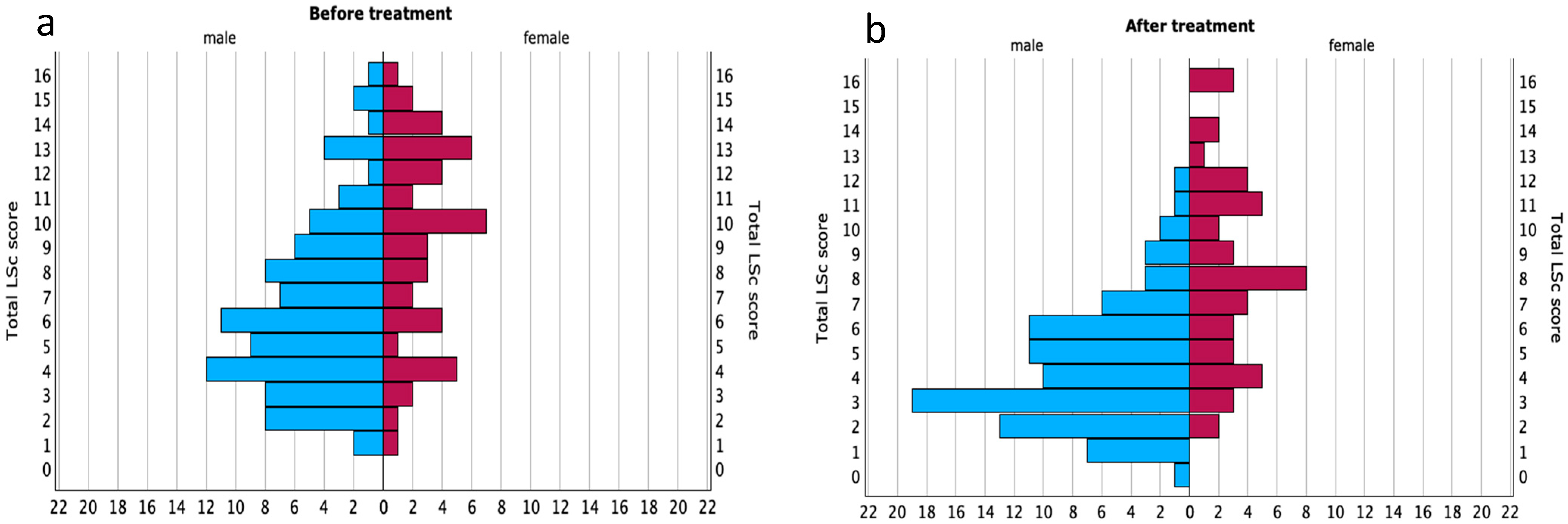

3.2. Lichen Sclerosus Score (LSc Score)

3.3. LSc Score in Relation to DLQI

3.4. LSc Score and Specific DLQI Questions

- Question 1: “Over the last week, how itchy, sore, painful or stinging has your skin been?”

- Question 8: “Over the last week, how much has your skin created problems with your partner or any of your close friends or relatives?”

- Question 9: “Over the last week, how much has your skin caused any sexual difficulties?”

- Before treatment, only Question 1 (symptoms) was significantly associated with LSc severity;

- After treatment, only Question 8 (interpersonal impact) showed a significant correlation;

- No significant association was found with Question 9 (sexual difficulties) at either timepoint.

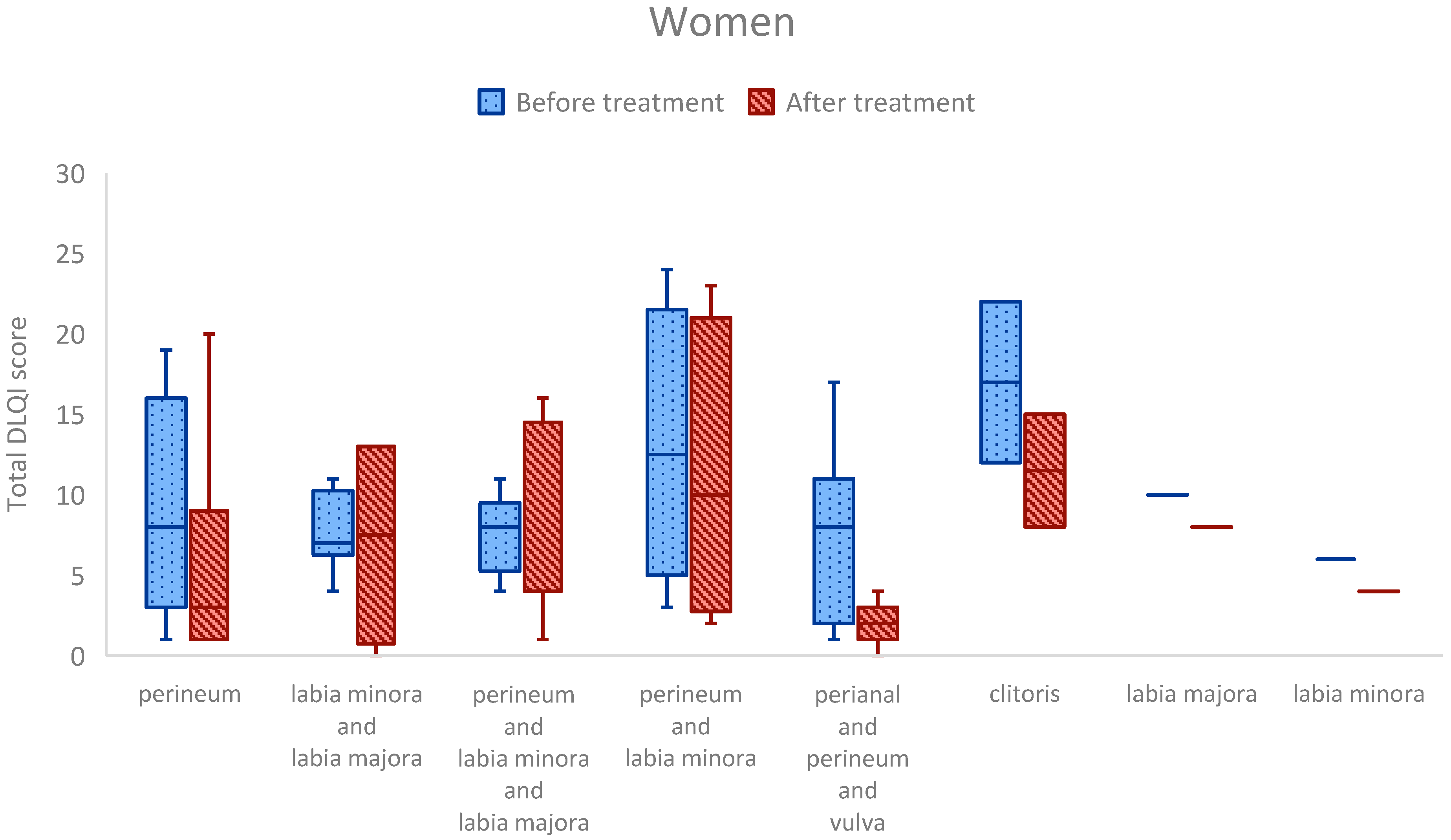

3.5. Anatomical Site of Involvement

3.6. Anatomical Site Comparisons: Clinically Relevant Trends

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oyama, N.; Hasegawa, M. Lichen Sclerosus: A Current Landscape of Autoimmune and Genetic Interplay. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naswa, S.; Marfatia, Y.S. Physician-administered clinical score of vulvar lichen sclerosus: A study of 36 cases. Indian J. Sex. Transm. Dis. AIDS 2015, 36, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyle, H.J.; Evans, J.C.; Vandergriff, T.W.; Mauskar, M.M. Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus Clinical Severity Scales and Histopathologic Correlation: A Case Series. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2023, 45, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erni, B.; Navarini, A.A.; Huang, D.; Schoetzau, A.; Kind, A.; Mueller, S.M. Proposition of a severity scale for lichen sclerosus: The “Clinical Lichen Sclerosus Score”. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtschig, G.; Kinberger, M.; Kreuter, A.; Simpson, R.; Gunthert, A.; van Hees, C.; Becker, K.; Ramakers, M.J.; Corazza, M.; Muller, S.; et al. EuroGuiderm guideline on lichen sclerosus-Treatment of lichen sclerosus. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 1874–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, D.A.; Papara, C.; Vorobyev, A.; Staiger, H.; Bieber, K.; Thaci, D.; Ludwig, R.J. Lichen sclerosus: The 2023 update. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1106318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol. Clin. 2010, 28, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerkovic Gulin, S.; Lundin, F.; Eriksson, O.; Seifert, O. Lichen Sclerosus-Incidence and Comorbidity: A Nationwide Swedish Register Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, P.; Jakobsson, M.; Heikinheimo, O.; Gissler, M.; Pukkala, E. Incidence of lichen sclerosus and subsequent causes of death: A nationwide Finnish register study. BJOG 2020, 127, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, M.; Russo, A.; Simonetti, O.; Borghi, A.; Corazza, M.; Piaserico, S.; Feliciani, C.; Calzavara-Pinton, P. Diagnosis and management of cutaneous and anogenital lichen sclerosus: Recommendations from the Italian Society of Dermatology (SIDeMaST). Ital. J. Dermatol. Venerol. 2021, 156, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Ghatage, P. Etiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis of Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus: A Scoping Review. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2020, 2020, 7480754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtschig, G.; Becker, K.; Gunthert, A.; Jasaitiene, D.; Cooper, S.; Chi, C.C.; Kreuter, A.; Rall, K.K.; Aberer, W.; Riechardt, S.; et al. Evidence-based (S3) Guideline on (anogenital) Lichen sclerosus. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, e1–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.M.; Dean, D.; Millard, P.R.; Charnock, F.M.; Wojnarowska, F. Cytokine alterations in lichen sclerosus: An immunohistochemical study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006, 155, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, S.M.; Ali, I.; Baldo, M.; Wojnarowska, F. The association of lichen sclerosus and erosive lichen planus of the vulva with autoimmune disease: A case-control study. Arch. Dermatol. 2008, 144, 1432–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravvas, G.; Muneer, A.; Watchorn, R.E.; Castiglione, F.; Haider, A.; Freeman, A.; Hadway, P.; Alnajjar, H.; Lynch, M.; Bunker, C.B. Male genital lichen sclerosus, microincontinence and occlusion: Mapping the disease across the prepuce. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panou, E.; Panagou, E.; Foley, C.; Kravvas, G.; Watchorn, R.; Alnajjar, H.; Muneer, A.; Bunker, C.B. Male genital lichen sclerosus associated with urological interventions and microincontinence: A case series of 21 patients. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, A.; Uthayakumar, A.; Watchorn, R.E.; Palmer, E.L.; Akel, R.; Kravvas, G.; Muneer, A.; Fuller, L.C.; Lewis, F.; Bunker, C.B. Urinary incontinence and female genital lichen sclerosus. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, L.; Huisman, B.W.; van der Wurff, M.; Naafs, R.G.C.; Schuren, F.H.J.; Sanders, I.; Smits, W.K.; Zwittink, R.D.; Burggraaf, J.; Rissmann, R.; et al. The vulvar microbiome in lichen sclerosus and high-grade intraepithelial lesions. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1264768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.L.; Perecman, A.; Sherman, A.; Sullivan, T.; Christ, K.; Hansma, A.; Burks, E.; Vanni, A.J. Urinary microbiome differences between lichen sclerosus induced and non-lichen sclerosus induced urethral stricture disease. World J. Urol. 2023, 41, 2495–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchorn, R.E.; van den Munckhof, E.H.A.; Quint, K.D.; Eliahoo, J.; de Koning, M.N.C.; Quint, W.G.V.; Bunker, C.B. Balanopreputial sac and urine microbiota in patients with male genital lichen sclerosus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgili, A.; Borghi, A.; Toni, G.; Minghetti, S.; Corazza, M. Prospective clinical and epidemiologic study of vulvar lichen sclerosus: Analysis of prevalence and severity of clinical features, together with historical and demographic associations. Dermatology 2014, 228, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, A.; Cota, C.; Orsini, D.; Cristaudo, A.; Tedesco, M. Male and female genital lichen sclerosus. Clinical and functional classification criteria. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2018, 35, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunthert, A.R.; Duclos, K.; Jahns, B.G.; Krause, E.; Amann, E.; Limacher, A.; Mueller, M.D.; Juni, P. Clinical scoring system for vulvar lichen sclerosus. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettolini, L.; Maione, V.; Arisi, M.; Rovaris, S.; Romano, C.; Tomasi, C.; Calzavara-Pinton, P.; Zerbinati, N.; Bighetti, S. The Influence of Genital Lichen Sclerosus on Sexual Health and Well-being: A Tripartite Comparative Analysis. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2025, 29, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittrup, G.; Morup, L.; Heilesen, T.; Jensen, D.; Westmark, S.; Melgaard, D. Quality of life and sexuality in women with lichen sclerosus: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpala, C.O.; Tekin, B.; Torgerson, R.R.; Wetter, D.A.; Nguyen, G.H. Treatment of lichen sclerosus with hydroxychloroquine: A Mayo Clinic experience. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, e240–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, M.; Chang, H.; Carr, C.; Barnard, A.; Reisch, J.; Mauskar, M.M. Patient questionnaire responses predict severe clinical signs in patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus: A retrospective cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 91, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basra, M.K.; Fenech, R.; Gatt, R.M.; Salek, M.S.; Finlay, A.Y. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: A comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 997–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, A.Y.; Khan, G.K. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1994, 19, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkle, D.; Wiersma, W.; Jurs, S. Applied Statistics for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, D. Significance of the Difference between Two Correlations Calculator [Software]. 2025. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=104 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Jerkovic Gulin, S.; Liljeberg, L.; Seifert, O. The impact of genital lichen sclerosus in men and women on quality of life: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2024, 10, e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheinis, M.; Green, N.; Vieira-Baptista, P.; Carriero, C.; Fischer, G.; Leclair, C.; Madnani, N.; Moyal-Barracco, M.; Selk, A. Adult Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus: Can Experts Agree on the Assessment of Disease Severity? J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2020, 24, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, R.; Lee, M.H.; Myers, A.; Song, J.; Abou Ghayda, R.; Kim, J.Y.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, S.B.; Koyanagi, A.; Jacob, L.; et al. Lichen Sclerosus and Sexual Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sex. Med. 2022, 19, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrows, L.J.; Creasey, A.; Goldstein, A.T. The treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus and female sexual dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M. Sexual function is adversely affected in the majority of men presenting with penile lichen sclerosus. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exclusion Criteria |

|---|

| Age < 18 years |

| Pregnancy |

| Current cancer diagnosis or treatment (except for extragenital basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma) |

| Prior circumcision for LSc before inclusion |

| Ongoing systemic anti-inflammatory or immunomodulating treatment or its discontinuation within the past week |

| Ongoing systemic antibiotic use or its discontinuation within the past week |

| Topical treatment (antibiotics, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors) on the affected area within the past week |

| Use of antiseptics or disinfectants on the affected area within 24 h of assessment |

| Inability to understand Swedish or provide informed consent |

| LSc Score Visit 1 | LSc Score Visit 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Pruritus (0–2) | ||

| Burning (0–2) | ||

| Soreness (0–2) | ||

| Pain during intercourse (0–2) | ||

| Erosions (0–2) | ||

| Sclerosis (0–2) | ||

| Redness (0–2) | ||

| Hypopigmentation (0–2) | ||

| Total LSc score (0–16) |

| Female Patients | Male Patients |

|---|---|

| Perineum | Glans penis |

| Labia minora | Foreskin |

| Labia majora | Coronal sulcus |

| Clitoris | Frenulum |

| Perianal area | Perianal area |

| Multisite involvement | Multisite involvement |

| Total (n = 136) | Men (n = 88) | Women (n = 48) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 62 (18–87) | 59 (18–86) | 64 (31–87) |

| Baseline LSc Score (IQR) | Follow-Up LSc Score (IQR) | Z-Score | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 136) | 7.0 (4.0–10.0) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | −4.357 | <0.001 * |

| Men (n = 88) | 6.0 (4.0–9.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | −4.568 | <0.001 * |

| Women (n = 48) | 10.0 (6.0–13.0) | 8.0 (5.0–11.0) | −1.413 | <0.158 |

| Overall Population (n = 136) | Men (n = 88) | Women (n = 48) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before R (p-Value) | After R (p-Value) | Before R (p-Value) | After R (p-Value) | Before R (p-Value) | After R (p-Value) | |

| Q1 | 0.604 (<0.001) | 0.512 (<0.001) | 0.628 (<0.001) | 0.470 (<0.001) | 0.495 (<0.001) | 0.194 (0.188) |

| Q8 | 0.374 (<0.001) | 0.351 (<0.001) | 0.487 (<0.001) | 0.254 (0.017) | 0.088 (0.550) | 0.299 (0.039) |

| Q9 | 0.389 (<0.001) | 0.241 (0.005) | 0.489 (<0.001) | 0.255 (0.017) | 0.189 (0.199) | 0.102 (0.489) |

| Localizations in Females | n (%) | Localizations in Males | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perineum | 19 (40) | Foreskin and corona | 36 (41) |

| Perineum and labia minora and majora | 8 (17) | Foreskin | 14 (16) |

| Perianal and perineum and vulva | 7 (15) | Glans, foreskin and corona | 13 (15) |

| Labia minora and labia majora | 6 (12) | Glans penis | 7 (8) |

| Perineum and labia minora | 4 (8) | Perianal and penis | 7 (8) |

| Clitoris | 2 (4) | Glans and foreskin | 5 (6) |

| Labia minora | 1 (2) | Sulcus corona penis | 4 (4) |

| Labia majora | 1 (2) | Perianal | 2 (2) |

| Perineum and labia majora | 0 (0) | Glans and corona | 0 (0) |

| Perianal | 0 (0) | Frenulum | 0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lundin, F.; Jeppsson, C.; Seifert, O.; Kravvas, G.; Jerkovic Gulin, S. Assessing Quality of Life in Genital Lichen Sclerosus: The Role of Disease Severity and Localization—A Swedish Prospective Cohort Study. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13030111

Lundin F, Jeppsson C, Seifert O, Kravvas G, Jerkovic Gulin S. Assessing Quality of Life in Genital Lichen Sclerosus: The Role of Disease Severity and Localization—A Swedish Prospective Cohort Study. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(3):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13030111

Chicago/Turabian StyleLundin, Filippa, Cassandra Jeppsson, Oliver Seifert, Georgios Kravvas, and Sandra Jerkovic Gulin. 2025. "Assessing Quality of Life in Genital Lichen Sclerosus: The Role of Disease Severity and Localization—A Swedish Prospective Cohort Study" Medical Sciences 13, no. 3: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13030111

APA StyleLundin, F., Jeppsson, C., Seifert, O., Kravvas, G., & Jerkovic Gulin, S. (2025). Assessing Quality of Life in Genital Lichen Sclerosus: The Role of Disease Severity and Localization—A Swedish Prospective Cohort Study. Medical Sciences, 13(3), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13030111