Diagnostic Accuracy of Sonazoid-Enhanced Ultrasonography for Detection of Liver Metastasis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

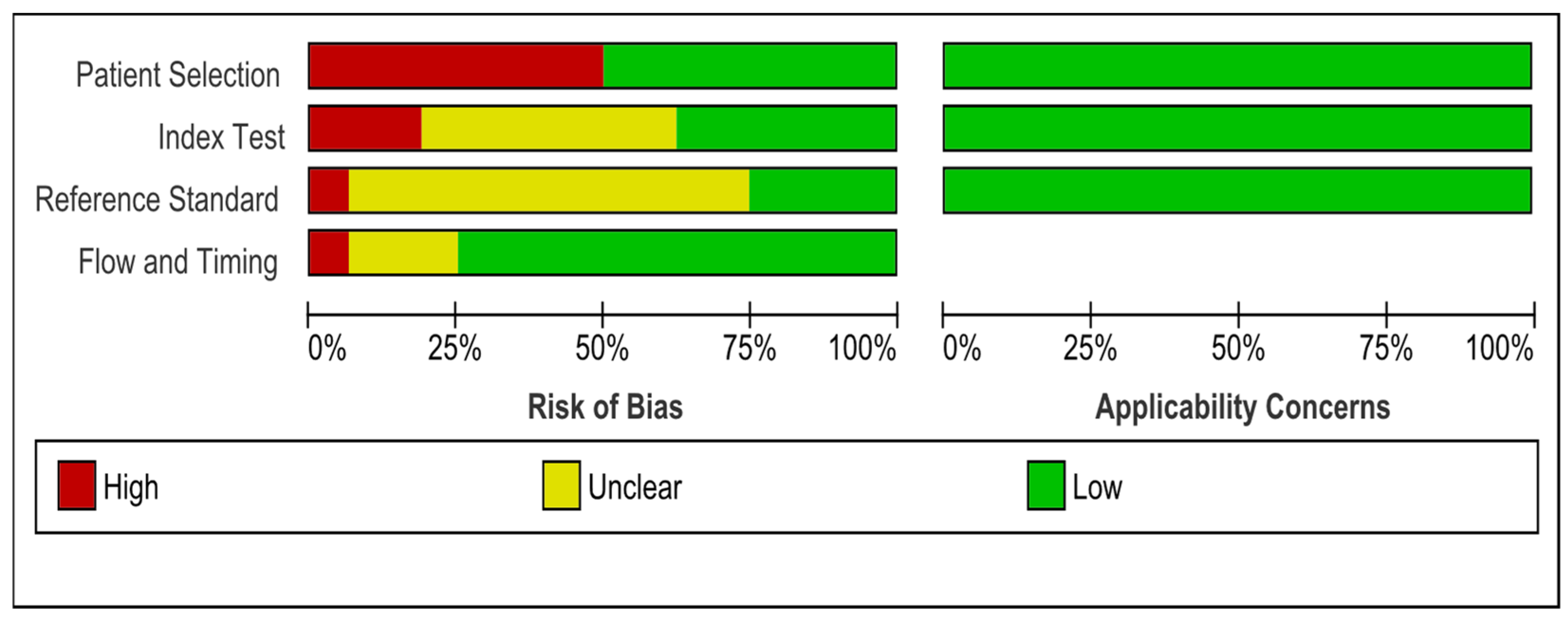

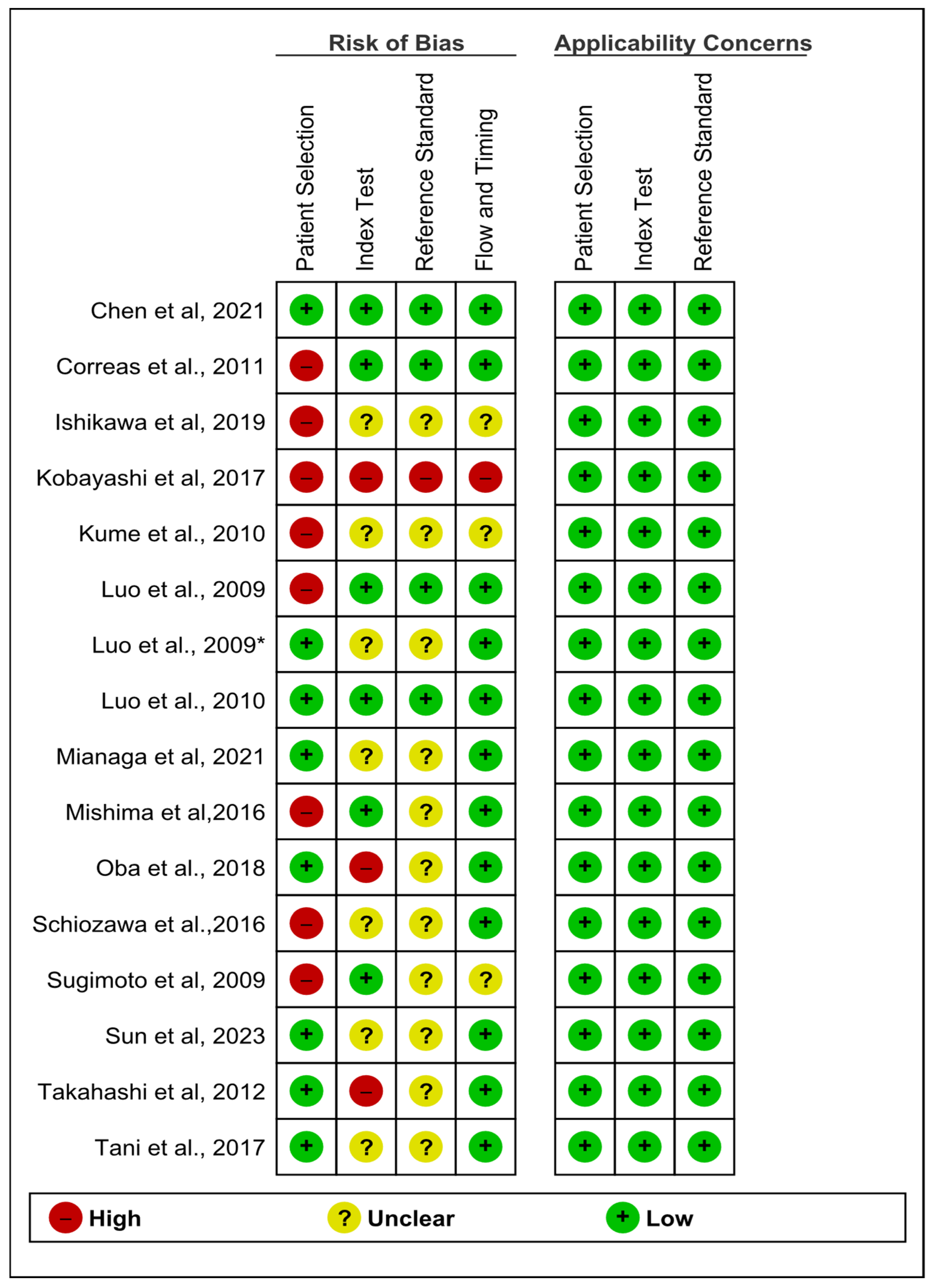

2.4. Critical Appraisal Tool and Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

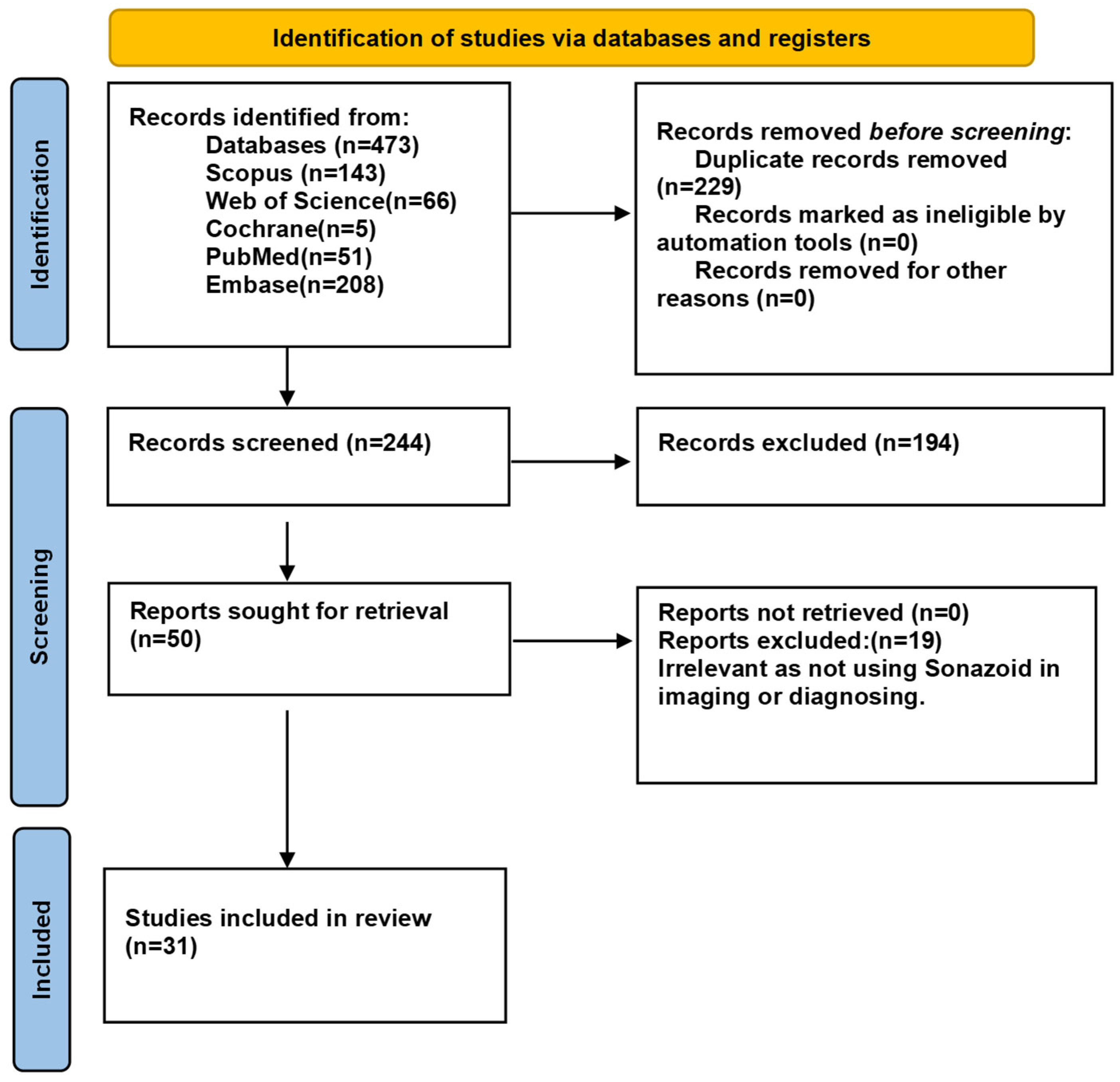

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Meta-Analysis Studies

3.4. Quality of Studies

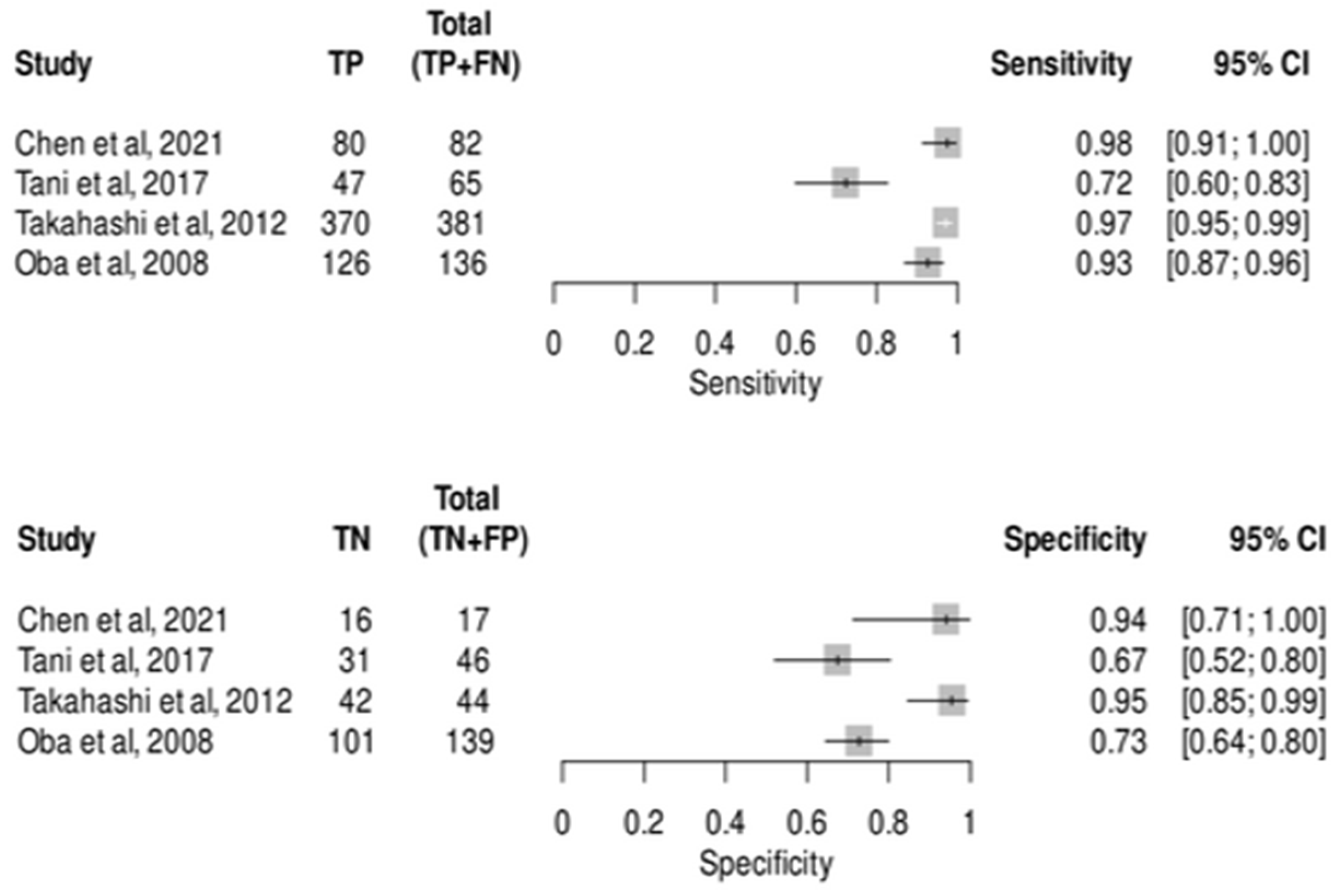

3.5. Diagnostic Test Accuracy Meta-Analysis for CEUS in Detecting Metastatic Lesions

3.6. Diagnostic Test Accuracy Meta-Analysis for CEIOS in Detecting Metastatic Lesions

3.7. Subgroup Analysis for CEUS in Detecting Metastatic Lesions

3.8. Studies Included in the Systematic Review

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaffer, C.L.; Weinberg, R.A. A Perspective on Cancer Cell Metastasis. Science 2011, 331, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.M.; Ma, B.; Taylor, D.L.; Griffith, L.; Wells, A. Liver metastases: Microenvironments and ex-vivo models. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1639–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Gao, W.; Lu, Y.; Lan, H.; Teng, L.; Cao, F. Mechanisms regulating colorectal cancer cell metastasis into liver (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2012, 3, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hahn, E.; Wick, G.; Pencev, D.; Timpl, R. Distribution of basement membrane proteins in normal and fibrotic human liver: Collagen type IV, laminin, and fibronectin. Gut 1980, 21, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.R.; Stoltzfus, K.C.; Lehrer, E.J.; Dawson, L.A.; Tchelebi, L.; Gusani, N.J.; Sharma, N.K.; Chen, H.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Zaorsky, N.G. Epidemiology of liver metastases. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020, 67, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Yi, N.J.; Son, S.Y.; You, T.; Suh, S.W.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.; Hong, G.; Lee, K.B.; Lee, K.-W.; et al. Histopathologic factors affecting tumor recurrence after hepatic resection in colorectal liver metastases. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2014, 87, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrand, J.; Nilsson, H.; Strömberg, C.; Jonas, E.; Freedman, J. Colorectal cancer liver metastases—A population-based study on incidence, management and survival. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Y.; Cohen, A.M.; Fortner, J.G.; Enker, W.E.; Turnbull, A.D.; Coit, D.G.; Marrero, A.M.; Prasad, M.; Blumgart, L.H.; Brennan, M.F. Liver resection for colorectal metastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leen, E.; Ceccotti, P.; Moug, S.J.; Glen, P.; MacQuarrie, J.; Angerson, W.J.; Albrecht, T.; Hohmann, J.; Oldenburg, A.; Ritz, J.P.; et al. Potential Value of Contrast-Enhanced Intraoperative Ultrasonography During Partial Hepatectomy for Metastases. Ann. Surg. 2006, 243, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.; Hohmann, J.; Oldenburg, A.; Skrok, J.; Wolf, K.J. Detection and characterisation of liver metastases. Eur. Radiol. Suppl. 2004, 14, P25–P33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Minami, Y.; Choi, B.I.; Lee, W.J.; Chou, Y.H.; Jeong, W.K.; Park, M.-S.; Kudo, N.; Lee, M.W.; Kamata, K.; et al. The AFSUMB Consensus Statements and Recommendations for the Clinical Practice of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound using Sonazoid. Ultrasonography 2020, 39, 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, K.; Moriyasu, F.; Miyahara, T.; Yuki, M.; Iijima, H. Phagocytosis of ultrasound contrast agent microbubbles by Kupffer cells. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2007, 33, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, R.; Matsumura, M.; Munemasa, T.; Fujimaki, M.; Suematsu, M. Mechanism of Hepatic Parenchyma-Specific Contrast of Microbubble-Based Contrast Agent for Ultrasonography. Investig. Radiol. 2007, 42, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyasu, F.; Itoh, K. Efficacy of Perflubutane Microbubble-Enhanced Ultrasound in the Characterization and Detection of Focal Liver Lesions: Phase 3 Multicenter Clinical Trial. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 193, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandai, M.; Koda, M.; Matono, T.; Nagahara, T.; Sugihara, T.; Ueki, M.; Ohyama, K.; Murawaki, Y. Assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma by contrast-enhanced ultrasound with perfluorobutane microbubbles: Comparison with dynamic CT. Br. J. Radiol. 2011, 84, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubner, M.G.; Mankowski Gettle, L.; Kim, D.H.; Ziemlewicz, T.J.; Dahiya, N.; Pickhardt, P. Diagnostic and procedural intraoperative ultrasound: Technique, tips and tricks for optimizing results. Br. J. Radiol. 2021, 94, 20201406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadon, M.; Costa, G.; Torzilli, G. State of the Art of Intraoperative Ultrasound in Liver Surgery: Current Use for Staging and Resection Guidance. Ultraschall Der Med.—Eur. J. Ultrasound 2014, 35, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Song, J.; Wu, M.; Chen, J. Contrast-Enhanced Intraoperative Ultrasonography with Kupffer Phase May Change Treatment Strategy of Metastatic Liver Tumors—A Single-Centre Prospective Study. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yin, S.; Xing, B.; Li, Z.; Fan, Z.; Yan, K. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound with SonoVue and Sonazoid for the Diagnosis of Colorectal Liver Metastasis After Chemotherapy. J. Ultrasound Med. 2023, 42, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Maruyama, H.; Kiyono, S.; Yokosuka, O.; Ohtsuka, M.; Miyazaki, M.; Matsushima, J.; Kishimoto, T.; Nakatani, Y. Histology-Based Assessment of Sonazoid-Enhanced Ultrasonography for the Diagnosis of Liver Metastasis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 2151–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Numata, K.; Morimoto, M.; Nozaki, A.; Ueda, M.; Kondo, M.; Morita, S.; Tanaka, K. Differentiation of focal liver lesions using three-dimensional ultrasonography: Retrospective and prospective studies. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2109–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, M.; Toh, U.; Iwakuma, N.; Takenaka, M.; Furukawa, M.; Akagi, Y. Evaluation of contrast Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography for the detection of hepatic metastases in breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2016, 23, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, A.; Mise, Y.; Ito, H.; Hiratsuka, M.; Inoue, Y.; Ishizawa, T.; Arita, J.; Matsueda, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Saiura, A. Clinical implications of disappearing colorectal liver metastases have changed in the era of hepatocyte-specific MRI and contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasonography. HPB 2018, 20, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. 2011. Available online: www.annals.org (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Study Quality Assessment Tools|NHLBI, NIH. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Zamora, J.; Abraira, V.; Muriel, A.; Khan, K.; Coomarasamy, A. Meta-DiSc: A software for meta-analysis of test accuracy data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2006, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaskill, P.; Gatsonis, C.; Deeks, J.; Harbord, R.; Takwoingi, Y. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Chapter 10 Analysing and Presenting Results. Available online: http://srdta.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Correas, J.M.; Low, G.; Needleman, L.; Robbin, M.L.; Cosgrove, D.; Sidhu, P.S.; Harvey, C.J.; Albrecht, T.; Jakobsen, J.A.; Brabrand, K.; et al. Contrast enhanced ultrasound in the detection of liver metastases: A prospective multi-centre dose testing study using a perfluorobutane microbubble contrast agent (NC100100). Eur. Radiol. 2011, 21, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Kawashima, H.; Ohno, E.; Tanaka, H.; Sakai, D.; Nishio, R.; Iida, T.; Suzuki, H.; Uetsuki, K.; Yamada, K.; et al. 592–Sequential Diagnosis of Liver Metastasis from Pancreatic Cancer Using Contrast-Enhanced Transabdominal Ultrasonography Following Endoscopic Ultrasonography in Comparison with Gd-Eob-Dtpa-Enhanced Mri. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, S-116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kume, Y.; Hiraoka, A.; Tazuya, N.; Hidaka, S.; Uehara, T.; Aki, H.; Miyamoto, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Michitaka, K.; Hirooka, M.; et al. Comparison with Contrast Enhance Ultrasonography with Sonazoid and FDG PET-CT for Hepatic Metastasis from Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, S187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Numata, K.; Morimoto, M.; Kondo, M.; Takebayashi, S.; Okada, M.; Morita, S.; Tanaka, K. Focal liver tumors: Characterization with 3D perflubutane microbubble contrast agent-enhanced US versus 3D contrast-enhanced multidetector CT. Radiology 2009, 251, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Numata, K.; Kondo, M.; Morimoto, M.; Sugimori, K.; Hirasawa, K.; Nozaki, A.; Zhou, X.; Tanaka, K. Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography for evaluation of the enhancement patterns of focal liver tumors in the late phase by intermittent imaging with a high mechanical index. J. Ultrasound Med. 2009, 28, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaga, K.; Kitano, M.; Nakai, A.; Omoto, S.; Kamata, K.; Yamao, K.; Takenaka, M.; Tsurusaki, M.; Chikugo, T.; Matsumoto, I.; et al. Improved detection of liver metastasis using Kupffer-phase imaging in contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS in patients with pancreatic cancer (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 93, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiozawa, K.; Watanabe, M.; Ikehara, T.; Matsukiyo, Y.; Kogame, M.; Kikuchi, Y.; Otsuka, Y.; Kaneko, H.; Igarashi, Y.; Sumino, Y. Comparison of contrast-enhanced ultrasonograpy with Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI in the diagnosis of liver metastasis from colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2017, 45, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, K.; Shiraishi, J.; Moriyasu, F.; Saito, K.; Doi, K. Improved detection of hepatic metastases with contrast-enhanced low mechanical-index pulse inversion ultrasonography during the liver-specific phase of sonazoid: Observer performance study with JAFROC analysis. Acad. Radiol. 2009, 16, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, K.; Shindoh, J.; Akamatsu, N.; Arita, J.; Kaneko, J.; Sakamoto, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Kokudo, N. Management of disappearing lesions after chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases: Relation between detectability and residual tumors. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Hasegawa, K.; Arita, J.; Hata, S.; Aoki, T.; Sakamoto, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Kokudo, N. Contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasonography using perfluorobutane microbubbles for the enumeration of colorectal liver metastases. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, K.; Harimoto, N.; Muranushi, R.; Hoshino, K.; Hagiwara, K.; Yamanaka, T.; Ishii, N.; Tsukagoshi, M.; Igarashi, T.; Watanabe, A.; et al. Evaluation of the use of intraoperative real-time virtual sonography with sonazoid enhancement for detecting small liver metastatic lesions after chemotherapy in hepatic resection. J. Med. Investig. 2019, 66, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edey, A.J.; Ryan, S.M.; Beese, R.C.; Gordon, P.; Sidhu, P.S. Ultrasound imaging of liver metastases in the delayed parenchymal phase following administration of Sonazoid using a destructive mode technique (Agent Detection Imaging). Clin. Radiol. 2008, 63, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroyoshi, J.; Ishizawa, T.; Abe, H.; Arita, J.; Akamatsu, N.; Kaneko, J.; Ushiku, T.; Hasegawa, K. Identification of Glisson’s Capsule Invasion During Hepatectomy for Colorectal Liver Metastasis by Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography Using Perflubutane. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakamada, K.; Ishido, N.; Kimura, M.; Nakai, N.; Wajima, Y.; Toyoki, S.; Narumi, D.K. Intraoperative Sonazoid-enhanced Ultrasonography Changes the Surgical Management for Colorectal Liver Metastasis: FC08-04. Hepatol. Int. 2011, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Itabashi, T.; Sasaki, A.; Otsuka, K.; Kimura, T.; Nitta, H.; Wakabayashi, G. Potential value of sonazoid-enhanced intraoperative laparoscopic ultrasonography for liver assessment during laparoscopy-assisted colectomy. Surg. Today 2014, 44, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nakano, H.; Ishida, Y.; Hatakeyama, T.; Sakuraba, K.; Hayashi, M.; Sakurai, O.; Hataya, K. Contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasonography equipped with late Kupffer-phase image obtained by sonazoid in patients with colorectal liver metastases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 3207–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanashima, A.; Tobinaga, S.; Abo, T.; Kunizaki, M.; Takeshita, H.; Hidaka, S.; Taura, N.; Ichikawa, T.; Sawai, T.; Nakao, K.; et al. Usefulness of sonazoid-ultrasonography during hepatectomy in patients with liver tumors: A preliminary study. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 103, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Saito, A.; Yoneda, Y.; Hayano, T.; Shiratori, K. Comparing enhancement and washout patterns of hepatic lesions between sonazoid-enhanced ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography. J. Med. Ultrason. 2010, 37, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramnarine, K.V.; Kyriakopoulou, K.; Gordon, P.; McDicken, N.W.; McArdle, C.S.; Leen, E. Improved characterisation of focal liver tumours: Dynamic power Doppler imaging using NC100100 echo-enhancer. Eur. J. Ultrasound 2000, 11, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tochio, H.; Sugahara, M.; Imai, Y.; Tei, H.; Suginoshita, Y.; Imawsaki, N.; Sasaki, I.; Hamada, M.; Minowa, K.; Inokuma, T.; et al. Hyperenhanced Rim Surrounding Liver Metastatic Tumors in the Postvascular Phase of Sonazoid-Enhanced Ultrasonography: A Histological Indication of the Presence of Kupffer Cells. Oncology 2015, 89 (Suppl. S2), 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, N.; Nagira, H.; Sannomiya, N.; Ikunishi, S.; Hattori, Y.; Kamida, A.; Koyanagi, Y.; Shimabayashi, K.; Sato, K.; Saito, H.; et al. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography in Evaluation of the Therapeutic Effect of Chemotherapy for Patients with Liver Metastases. Yonago Acta Med. 2016, 59, 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Uetake, H.; Tanaka, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Sugihara, K.; Arii, S. Fate of metastatic foci after chemotherapy and usefulness of contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasonography to detect minute hepatic lesions. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2012, 19, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, K.; Ueno, M.; Ozawa, S.; Kiriyama, S.; Shigekawa, Y.; Yamaue, H. Combined Use of Contrast-Enhanced Intraoperative Ultrasonography and a Fluorescence Navigation System for Identifying Hepatic Metastases. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 2953–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, Y.; Kudo, M.; Hatanaka, K.; Kitai, S.; Inoue, T.; Hagiwara, S.; Chung, H.; Ueshima, K. Radiofrequency ablation guided by contrast harmonic sonography using perfluorocarbon microbubbles (Sonazoid) for hepatic malignancies: An initial experience. Liver Int. 2010, 30, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, E.; Shiina, S.; Tateishi, R.; Masuzaki, R.; Enooku, K.; Sato, T.; Imamura, J.; Goto, T.; Sugioka, Y.; Ikeda, H.; et al. Utility of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasonography with Sonazoid in Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) for Liver metastasis. Hepatol Int. 2009, 3, 86–220. [Google Scholar]

- Tsilimigras, D.I.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Paredes, A.Z.; Moris, D.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Cloyd, J.M.; Pawlik, T.M. Disappearing liver metastases: A systematic review of the current evidence. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 29, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, E.K.; Forsberg, F.; Aksnes, A.K.; Merton, D.A.; Liu, J.B.; Tornes, A.; Johnson, D.; Goldberg, B.B. Enhanced detection of blood flow in the normal canine prostate using an ultrasound contrast agent. Investig. Radiol. 2000, 35, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, M.; Ueshima, K.; Osaki, Y.; Hirooka, M.; Imai, Y.; Aso, K.; Numata, K.; Kitano, M.; Kumada, T.; Izumi, N.; et al. B-Mode Ultrasonography versus Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography for Surveillance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Prospective Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Liver Cancer 2019, 8, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsberg, F.; Piccoli, C.W.; Liu, J.B.; Rawool, N.M.; Merton, D.A.; Mitchell, D.G.; Goldberg, B.B. Hepatic tumor detection: MR imaging and conventional US versus pulse-inversion harmonic US of NC100100 during its reticuloendothelial system-specific phase. Radiology 2002, 222, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, K.; Moriyasu, F.; Saito, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Itoi, T. Multimodality imaging to assess immediate response following irreversible electroporation in patients with malignant hepatic tumors. J. Med. Ultrason. 2017, 44, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.G.E.D.; Kader, M.H.A.; Arafa, H.M.; Ali, S.A. Characterization of focal liver lesions using sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) microbubble contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2021, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, Y.; Nishida, N.; Kudo, M. Therapeutic response assessment of RFA for HCC: Contrast-enhanced US, CT and MRI. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 4160–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muaddi, H.; Silva, S.; Choi, W.J.; Coburn, N.; Hallet, J.; Law, C.; Cheung, H.; Karanicolas, P.J.; Karanicolas, P.J.; Surg, A. When is a Ghost Really Gone? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Accuracy of Imaging Modalities to Predict Complete Pathological Response of Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases After Chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 6805–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Albrecht, T.; Blomley, M.J.; Heckemann, R.A.; Cosgrove, D.O.; Wolf, R. Heterogeneous delayed enhancement of the liver after ultrasound contrast agent injection—A normal variant. J. Ultrasound Med. 2002, 28, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottomo, S.; Rikiyama, T.; Egawa, S.; Katayose, Y.; Motoi, F.; Yamamoto, K.; Yoshida, H.; Miura, T.; Funayama, Y.; Unno, M. Chemotherapy-induced reduction of rectal cancer metastasis to the liver visualized by intraoperative Sonazoid™ contrast-enhanced ultrasound. J. Japan Soc. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2011, 44, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sugimoto, K.; Shiraishi, J.; Moriyasu, F.; Doi, K. Computer-aided diagnosis of focal liver lesions by use of physicians’ subjective classification of echogenic patterns in baseline and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Acad. Radiol. 2009, 16, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, K.; Moriyasu, F.; Takeuchi, H.; Kojima, M.; Ogawa, S.; Sano, T.; Furuichi, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nakamura, I. Optimal injection rate of ultrasound contrast agent for evaluation of focal liver lesions using an automatic power injector: A pilot study. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranquart, F. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound with Sonazoid for the imaging and diagnosis of colorectal liver metastasis. J. Ultrasound Med. 2023, 42, 1371–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Shiozawa, K.; Ikehara, T.; Ichimori, M.; Shinohara, M.; Kikuchi, Y.; Ishii, K.; Nemoto, T.; Shibuya, K.; Sumino, Y. Ultrasonography of intrahepatic bile duct adenoma with renal cell carcinoma: Correlation with pathology. J. Med. Ultrason. 2013, 40, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.R.; Burns, P.N. Liver mass evaluation with ultrasound: The impact of microbubble contrast agents and pulse inversion imaging. Semin. Liver Dis. 2001, 21, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sun, D.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, H.; et al. Protocol of Kupffer phase whole liver scan for metastases: A single-center prospective study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 911807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Song, J.; Li, C. Role of Sonazoid enhanced ultrasound assistant laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation in treating liver malignancy—A single-center retrospective cohort study. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 9075–9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, R.; Sakamoto, A.; Nagata, Y.; Nishijima, N.; Ikeda, A.; Matsuo, H.; Okada, M.; Ashida, S.; Taniguchi, T.; Kimura, T.; et al. Visualization of blood drainage area from hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma on ultrasonographic images during hepatic arteriogram: Comparison with depiction of drainage area on contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Hepatol. Res. 2012, 42, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuta, J.; Tamai, H.; Mori, Y.; Shingaki, N.; Maeshima, S.; Shimizu, R.; Maeda, Y.; Moribata, K.; Niwa, T.; Deguchi, H.; et al. Kupffer imaging by contrast-enhanced sonography with perfluorobutane microbubbles is associated with outcomes after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Ultrasound Med. 2016, 35, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, A.; Ichiryu, M.; Tazuya, N.; Ochi, H.; Tanabe, A.; Nakahara, H.; Hidaka, S.; Uehara, T.; Ichikawa, S.; Hasebe, A.; et al. Clinical translation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma following the introduction of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with Sonazoid. Oncol. Lett. 2010, 1, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hatanaka, K.; Chung, H.; Kudo, M.; Haji, S.; Minami, Y.; Maekawa, K.; Hayaishi, S.; Nagai, T.; Takita, M.; Kudo, K.; et al. Usefulness of the post-vascular phase of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with Sonazoid in the evaluation of gross types of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2010, 78 (Suppl. S1), 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study ID | Country | Design | Age Mean (Range) | Sex (M/F) | Aim | Type of Lesions | Number of Lesions | Reference Test | Conclusion and Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al., 2021 [18] | China | Prospective study | 59.6 (48.3–70.9) | 20/07 | To compare the diagnostic performance of CE-IOUS with Kupffer-phase imaging in metastatic liver tumors. | Liver metastasis/others | 82/17 | 88 through histopathology and 11 through various imaging modalities | CE-IOUS with Sonazoid showed high sensitivity (97.5%) and specificity for detecting liver lesions, outperforming MRI (93.3%) and CEUS (97.1%) during the Kupffer phase. It also identified additional lesions, highlighting its potential superiority in diagnosing liver metastases and guiding treatment decisions. |

| Luo et al., 2009 [32] | Japan | Retrospective study | 62 (47.3–76.7) | 90/49 | To compare the diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced three-dimensional ultrasonography to contrast-enhanced three-dimensional computed tomography in detecting liver tumors. | Liver metastasis | 33 | Biopsy, surgery, or MR imaging | Readers 1 and 2 achieved 83% concordance between US and CT findings in 139 lesions with high inter-modality and inter-reader concordance. Both modalities were equally capable of diagnosis. Contrast-enhanced 3D US holds the potential for characterizing focal liver tumors. |

| HCC | 77 | ||||||||

| Luo et al., 2009 [33] | Japan | Prospective study | 64 (50.6–77.4) | 78/64 | To evaluate late-phase enhancement patterns of focal liver tumors using Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography with intermittent high mechanical index imaging. | Liver metastasis | 61 | Histopathology | Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasound with high mechanical index intermittent imaging effectively assessed late-phase enhancement patterns of liver tumors. It had good diagnostic accuracy for the distinction between HCC, metastases, hemangiomas, and FNH, with excellent inter-reader agreement, suggesting its utility in the characterization of liver tumors. |

| HCC | 109 | 72 lesions by CT and MRI and 37 lesions by histopathology | |||||||

| Luo et al., 2010 [21] | Japan | Retrospective and prospective studies | 67.4 (61.0–73.8) | Prospective: 90/73, retrospective study: 67/52 | To differentiate focal liver lesions based on enhancement patterns using three-dimensional ultrasonography (3D US) with a perflubutane-based contrast agent. | Liver metastasis | 28 | CT and MRI | Contrast-enhanced 3D ultrasound effectively distinguishes liver tumors with high accuracy, matching or exceeding 2D ultrasound. It provides valuable spatial perspectives, aiding in the differentiation of hepatocellular carcinomas, metastases, hemangiomas, and focal nodular hyperplasia. |

| HCC | 70 | ||||||||

| Minaga et al., 2021 [34] | Japan | Retrospective study | 69 | 291/209 | To assess Kupffer-phase imaging in CH-EUS for detecting liver metastases from pancreatic cancer, comparing it with B-mode EUS. | Liver metastasis | 116 | Histopathological findings of EUS-FNA samples and follow-up imaging examinations | CH-EUS with Kupffer-phase imaging had greater diagnostic accuracy (98.4%) for left-lobe liver metastasis in pancreatic cancer patients than CE-CT (90.6%) and FB-EUS (93.4%). It was particularly good at detecting small metastases (<10 mm) and impacted staging in 2.1% of the patients. These findings indicate that CH-EUS is an important tool for pretreatment assessment. |

| 36 | |||||||||

| Sugimoto et al., 2009 [36] | Japan | Prospective study | 69.5 (59.3–79.7) | 21/16 | To compare B-mode ultrasonography (US) alone and in combination with B-mode and contrast-enhanced (Sonazoid) late-phase pulse-inversion US for the detection of hepatic metastases by use of jackknife free-response receiver-operating characteristic (JAFROC) analysis. | HCC, Metastasis, or hemangioma | 74 | Histological examination after surgical resection (10 lesions), US-guided biopsy (110 lesions), or contrast-enhanced CT and/or MRI for hemangioma | The integration of liver ultrasound cine clips with contrast enhancement and B-mode ultrasound improves detection sensitivity for hepatic metastases (41.6% to 72.2%), reduces false positives, and raises the figure of merit (0.44 to 0.76). The technique helps clinicians to diagnose tumors more accurately. |

| 33 | |||||||||

| 30 | |||||||||

| Kume et al., 2010 [31] | Japan | Prospective study | Not mentioned | To analyze the diagnostic accuracy of Sonazoid for detecting hepatic metastases from GIT cancers and to compare it with FDG PET-CT results. | Liver metastasis | 109 | In the cases with different results between CEUS and PET-CT, results of hepatic resection, dynamic CT, and/or magnetic resonance imaging, as well as followed-up clinical courses in some cases, were used for assistant diagnostic methods | Among 109 subjects, 34 had upper gastrointestinal tract cancer (esophageal 4, gastric 29, duodenal 1), and 76 had colorectal cancer (1 case was complicated with gastric cancer); the sensitivities and specificities of CEUS were 89.7% and 97.5%, respectively. In conclusion, CEUS with Sonazoid had similar efficacy in diagnosing hepatic metastasis as PET-CT. | |

| Sun et al., 2023 [19] | China | Prospective study | 56.0 (47.3–64.7) | 21/8 | To compare the diagnostic efficacy of SonoVue and S-CEUS in detecting colorectal liver metastasis (CRLM) after chemotherapy. | Colorectal liver metastasis | 297 | Histopathology for surgically removed lesions or intraoperative ultrasound with MRI for unresected liver lesions | In a study with 348 liver lesions, including 297 colorectal metastases, SonoVue showed significantly better diagnostic accuracy (64.7% vs. 54.0%) and sensitivity (63.3% vs. 50.5%) than Sonazoid. Both methods had similar specificity (72.5% vs. 74.5%). Notably, 40 metastases were mischaracterized by Sonazoid as benign lesions. The conclusion is that SonoVue performs better in diagnosing colorectal metastases after chemotherapy. |

| 297 | |||||||||

| Kobayashi et al., 2017 [20] | Japan | Retrospective study | 66.4 (58.0–74.8) | 62/36 | The study aimed to verify the effectiveness of S-CEUS in detecting, diagnosing, and providing additional benefits in the management of patients with liver tumors suspected to be metastatic. | Liver metastasis | 121 | Histopathological examination | S-CEUS had 95.0% sensitivity, 44.4% specificity, and 85.8% accuracy in the diagnosis of metastases. Accuracy was diminished by increased BMI and lesion depth, and management was impacted by S-CEUS in 8.2% of patients. The addition of S-CEUS improves diagnostic quality and decision-making for liver metastasis assessment. |

| Mishima et al.,2016 [22] | Japan | 59 (48.0–68.0) | Females Only | To assess the effectiveness of Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography in detecting hepatic metastases in breast cancer patients. comparing the clinical efficacy and sensitivity of this technique with conventional contrast-unenhanced B-mode ultrasonography. | Liver metastasis | 84 | CT and MRI | In a study with 79 nodules, Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography (SEUS) showed high sensitivity (98.8%) and accuracy (98.7%) in detecting liver metastases in breast cancer patients, outperforming conventional B-mode ultrasound. SEUS had lower false positive and false negative rates and detected additional tumors. The study concluded that Sonazoid is safe, and that SEUS is more effective than B-mode ultrasound, particularly for small lesions under 14 mm in diameter. | |

| Correas et al., 2011 [29] | Austria | Prospective study | 62.4 (52.3–72.5) | 1.4/1 | To analyze perfluorobutane microbubble (NC100100) CEUS doses for optimal detection of liver metastases in patients with non-hepatic primary malignancies. | Liver metastasis | 165 | Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI | In a study with 92 patients and 165 liver metastases, contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) at a 0.12 μL/kg dose demonstrated significantly higher sensitivity (78%) and accuracy (70%) compared to other doses, highlighting the dose-dependent nature of CEUS for detecting liver metastases. |

| 32 | |||||||||

| 40 | |||||||||

| 36 | |||||||||

| 57 | |||||||||

| Shiozawa et al., 2016 [35] | Japan | Prospective study | 66.0 (54.8–77.2) | 1/2 | To compare contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) using Sonazoid with Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI (EOB-MRI) in the diagnosis of liver metastases in patients with colorectal cancer. | Liver metastasis | 109 | Histopathology and imaging | In the study, both contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and EOB-MRI detected liver metastases, with CEUS showing higher specificity (84.5% vs. 70.8%) and positive predictive value (97.1% vs. 93.7%) compared to EOB-MRI. Overall diagnostic accuracy was 90.2% for CEUS and 91% for EOB-MRI. The conclusion is that CEUS is more specific for diagnosing liver metastases than EOB-MRI. |

| Ishikawa et al., 2019 [30] | Japan | Prospective study | Not mentioned | 26/15 | To assess the diagnostic efficacy of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography (CE-EUS) using Sonazoid for pancreatic cancer, with a focus on liver metastases, comparing the results with contrast-enhanced transabdominal ultrasonography (CEUS) following CE-EUS and Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI (EOB-MRI). | Liver metastasis | 30 | Histopathological examination | In the study, patients undergoing contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography (CE-EUS) for pancreatic cancer were analyzed. EOB-MRI demonstrated 100% sensitivity, 88.2% specificity, and 93.7% positive predictive value (PPV) for liver metastases, while CEUS showed 83.3% sensitivity, 100% specificity, and 100% PPV. CEUS, especially valuable in differentiating liver metastasis from abscess, exhibited higher specificity and PPV than EOB-MRI. |

| Oba et al., 2018 [23] | Japan | 59.0 (43.5–74.5) | 71/29 | To investigate the clinical implications of disappearing liver metastases from colorectal cancer after chemotherapy in the era of modern imaging studies. | Colorectal liver metastasis | 136 | Histological examination | In 59 patients with 275 colorectal liver metastases (DLMs), 26% of lesions were identified by EOB-MRI, 92% of which were viable at the time of resection. Together, EOB-MRI and CE-IOUS identified and resected 60% of DLMs, 77% of which contained viable disease. Non-resected lesions had a recurrence rate of 14% at 27 months. Sequential use of EOB-MRI and CE-IOUS effectively detect clinically significant DLMs. | |

| Takahashi et al., 2012 [38] | Japan | Prospective study | 63.0 (48.6–77.4) | 67/35 | To evaluate the effectiveness of contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasonography (CE-IOUS) using lipid-stabilized perfluorobutane microbubbles in detecting and enumerating colorectal liver metastases. | Colorectal liver metastasis | 381 | Histopathology for resected specimens and the results of follow-up studies using CT and/or MRI carried out within 3–6 months after the operation | In a study of 102 patients with 315 lesions, contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasound (CE-IOUS) identified more lesions than conventional examination. CE-IOUS showed 97.1% sensitivity, 59.1% specificity, and 93.2% accuracy, leading to a change in the surgical plan in 14.7% of cases. The conclusion is that CE-IOUS provides additional information beyond preoperative imaging and conventional intraoperative examinations. |

| Tani et al., 2017 [37] | Japan | Retrospective study | 63.2 (49.0–77.4) | 10:10 | To assess the detectability of EOB-MRI and CE-IOUS for residual disease in disappearing colorectal liver metastases (DLMs) and to explore optimal management strategies for DLMs. | Colorectal liver metastasis | 619 | Histopathology and various imaging modalities | In the study, EOB-MRI outperformed CE-IOUS in detecting residual tumors for colorectal liver metastases (DLMs). EOB-MRI had higher accuracy in predicting residual disease (0.90 vs. 0.70). Of the undetected lesions by CE-IOUS that regrew after surgery, 81.8% were identified on EOB-MRI. The conclusion suggests the superiority of EOB-MRI for detecting residual tumors, emphasizing the need for maximum resection attempts for lesions visualized in EOB-MRI. |

| Study ID | Country | Design | Age (Mean) | Sex (M/F) | Aim | Type of Lesions | Number of Lesions | Reference Test | Conclusion and Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Araki et al., 2019 [39] | Japan | Cohort | 55 | 2/1 | In this article, the authors reported the significance of RVS-CEUS as a novel technique in hepatic resection for detecting small liver lesions. | Liver metastasis | 10 | Dynamic CT and EOB-MRI | The study found that intraoperative real-time virtual sonography with contrast-enhanced ultrasound (RVS-CEUS) had a 90% detection rate for small liver lesions (<10 mm) post-chemotherapy, outperforming CE-CT (50%) and EOB-MRI (100%). RVS-CEUS detected lesions as small as 3.0 mm with a maximum depth of 43.5 mm, making it a promising technique for hepatic resection. |

| Hakamada et al., 2011 [42] | Japan | Prospective study | Not mentioned | Evaluated Sonazoid-enhanced CE-IOUS for visualizing colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) vascularity and Kupffer cells, comparing its performance with dynamic CT, MR, and PET-CT. Aimed to enhance the precision of detecting smaller lesions in the context of evolving chemotherapy and targeted therapy for initially unresectable CRLM. | Colorectal liver metastasis | 59 | Intra-operative (patients undergoing hepatectomy) | CE-IOUS with Sonazoid detected tumors in the post-vascular phase at 92.5%, surpassing conventional US (75.4%), CT (85.5%), EOB-MRI (92.5%), DWI-MRI (85.7%), and PET-CT (51.8%)—additional detection by CE-IOUS altered procedures in 15.6% of patients, facilitating R0 resections. Conclusively, CE-IOUS with Sonazoid is a valuable tool for assessing smaller colorectal liver metastases undetected by conventional modalities, potentially enhancing patient outcomes. | |

| Uchiyama et al., 2010 [51] | Japan | ? | 71.8 | 3/5 | The study aimed to assess the efficacy of combining CE-IOUS and fluorescence navigation (photo dynamic eye with indocyanine green) for identifying colorectal metastatic lesions. This was compared with preoperative contrast-enhanced CT and gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI. | Colorectal liver metastasis | 52 | Histopathology of biopsy or resected tissue | In the study, 56 lesions were identified, with 52 confirmed as metastases and 4 as benign tumors. Metastases detected by CE-IOUS and PDE [51] were higher than those by MDCT and EOB-MRI [46]. The combined use of CE-IOUS and PDE improved diagnostic sensitivity compared to MDCT and EOB-MRI (98.1% vs. 88.5%). The conclusion is that concomitant use of CE-IOUS with Sonazoid and the PDE system is a useful and safe method in addition to CT or MRI for identifying metastases. |

| Minami et al., 2010 [52] | Japan | Retrospective | 65.8 | 51/15 | Conventional contrast harmonic sonography has a technical problem of a short enhancement time during the targeting of hepatic malignancies for radiofrequency (RF) ablation. This study investigated the effectiveness of contrast harmonic sonographic guidance using perfluorocarbon microbubbles (Sonazoid) during RF ablation of hepatic malignancies. | HCC and secondary liver malignancies | 108 | CT | Findings: Based on sonography, the maximum diameters of all the tumors varied from 0.7 to 3.5 cm (mean ± SD, 1.7 ± 0.9). In 62 (94%) of the 66 patients, complete tumor necrosis was attained with a single RF ablation treatment. For the remaining four patients (6%), two sessions were needed. There were 1.1 0.3 therapy sessions on average. Of the 108 malignant hepatic tumors, 105 (97%) had a defect with a margin during the post-vascular period. During a follow-up period of 1–12 months (mean, 4.3 months), the clinical courses were excellent, with no evidence of local tumor progression. |

| Uetake et al., 2012 [50] | Japan | Cohort | _ | _ | Chemotherapy has changed the strategy for hepatic metastasis. Unresectable hepatic metastases can become resectable after chemotherapy. Contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasonography (CE-IOUS) helps to detect undetectable hepatic lesions. Even shrunken tumors have viable cancer cells, and CE-IOUS helps to detect minute foci. | Colorectal cancer | 57 | Preoperative CT and pathological examination | Before chemotherapy, 57 metastatic lesions were found. CE-IOUS used perflubutane to demonstrate thirty lesions, which were subsequently excised. Twelve of the samples did not show tumor cells in the pathological investigation. There were thirty resected lesions in total. All patients had pathological liver damage of grade 1 or less, and none of them experienced any major postoperative complications. |

| Ueda et al., 2016 [49] | Japan | Retrospective | 73.8 | 3/2 | This study investigated whether changes in the time–intensity curve (TIC) of CEUS are useful indicators of the therapeutic effect of chemotherapy. | Rectal, gastric, and esophageal | _ | CT | Out of the five TIC parameters that were investigated, the area under the curve and the ROC of the wash-in slope indicated that the therapeutic impact of chemotherapy was superior to the other three characteristics. (ii) Two of the five patients had their TIC parameters evaluated following a single chemotherapy cycle, and modifications in the area under the curve and the slope of washing were in good agreement with computed tomography results that indicated the therapeutic impact following the fourth chemotherapy cycle. |

| Tochio et al., 2015 [48] | Japan | Cohort | HER-positive: 67, HER-negative: 62 | HER-positive: 6/2 HER-negative: 4/1 | A hyper-enhanced rim (termed “HER”) in the post-vascular phase is detected in some cases of liver metastasis by Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography (US). Here, the association of the HER with histological features was investigated to clarify the cause of this characteristic imaging pattern. | Liver metastasis | 13 | Histopathology | The distribution density of CD68-positive cells in the HER-positive group (n = 8) was 2.9 ± 0.9, substantially greater than that in the HER-negative group (1.0 ± 0.3) (p < 0.05). In the vicinity of the tumor, inflammatory cell infiltrates, including CD8-positive lymphocytes, were found in all HER-positive instances, whereas fibrosis was noted in all HER-negative cases. In the HER-negative group, the tumor’s necrotic region was noticeably bigger. |

| Ramnarine et al., 2000 [47] | UK | Cohort | Age range of, 38–77 years | _ | To assess the vascularization of focal hepatic tumors using NC100100 dynamic power Doppler imaging and to quantify the power Doppler signal intensity (PDSI) to provide contrast agent wash-in (PDSI–time) curves of focal liver lesions. | Liver metastasis | 22 | Histopathology | The PDSI–time curves within hemangiomas were flat, while the PDSI increased quickly in liver metastases. Of the participants with liver metastases, eleven had a significant rise in PDSI within the tumor, whereas just one had a hemangioma. Four patients had hemangiomas visible surrounding an improved rim. The dose of the contrast agent and the peak PDSI inside metastases did not appear to be correlated. |

| Patel et al., 2010 [46] | Japan | Cohort | 25 to 85 | 11/24 | To compare Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasound (SEUS) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) enhancement and washout patterns in hepatic lesions. | HCCs_(ICCs)_metastatic lesions_FNHs_UBLs_AMLs | 61 | Histopathology | On both SEUS and CECT, all 61 lesions (100%) exhibited vascular enhancement. For the 61 lesions, there was a 93.4% “washout/no washout” agreement between SEUS and CECT (j coefficient: 0.816). There were 42 malignant lesions in total. Washout was seen in 38 lesions (90.5%) on both SEUS and CECT. Washout was seen on SEUS but not on CECT in the remaining four malignant lesions, three of which had fibrosis (two intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and one scirrhous hepatocellular carcinoma). The agreement between SEUS and CECT for the 19 benign lesions was 100% (j coefficient: 1), with 7 lesions exhibiting washout using both techniques and 12 lesions exhibiting no washout using either technique. |

| Nanashima et al., 2010 [45] | Japan | Case-control | 68.1 | 34/16 | To elucidate different facets of IOUS. To achieve this, we evaluated the contrast-media IOUS employing Sonazoid in 50 hepatectomy patients who had liver tumors, as well as the viability and constraints of this technique. The outcomes were compared historically with patients who had a hepatectomy between 2004 and 2006 using traditional IOUS. | HCC, ICC, or colorectal liver metastasis | The cancers included gastrointestinal stromal tumor in 1 case, benign hematoma in 1 case, colorectal liver metastases in 14 cases, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in 3 cases, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in 25 individuals. In the majority of instances, liver tumors were easily identified as perfusion defects. On the Sonazoid IOUS, small lesions (<1 cm), extra-capsular tumor development, and portal vein tumor thrombus were also plainly seen. In five cases, small occult tumors were discovered. Early vascular findings allowed for a differential diagnosis with suspected non-tumorous lesions and benign masses. The proportion of patients with positive surgical margin (0%) tended to be lower than that of the control group (P¼0.073) when compared to hepatectomy for HCC under traditional IOUS. | ||

| Nakano et al., 2008 [44] | Japan | Brief clinical report | To detect occult metastases during hepatectomy in patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases (CRCLM). Sonazoid, a novel microbubble agent that produces a parenchyma-specific contrast image based on its accumulation in the Kupffer cells, was used in contrast-enhanced intraoperative ultrasound sonography (CE-IOUS). | Colorectal liver metastasis | CT and MRI | Sonazoid was injected into CE-IOUS, which produced early vascular and sinusoidal phase images for ten minutes and late Kupffer phase images for up to thirty minutes. The eight patients’ metastatic lesions were not found to be new by IOUS. However, in two of the eight patients, a new metastatic lesion was discovered during the late Kupffer-phase Sonazoid imaging. These recently discovered tumors were removed during a second hepatectomy, and histological analysis revealed that they were metastases. | |||

| Edey et al., 2008 [40] | 67.3 | 10/16 | To determine whether phase-inversion imaging and delayed-phase liver imaging with a destructive imaging mode can yield information that is comparable to phase-inversion imaging in terms of liver metastasis detection and conspicuity. | Liver metastasis | Histopathology after biopsy of a focal lesion or tissue resection | Sixteen patients were included (ten men and six women), with a mean age of 67.3 years (range: 48–83 years). Group A n ¼ 1, Group B n ¼ 8, Group CI n ¼ 1, Group CII n ¼ 4, and Group CIII n ¼ 2 were the divisions based on CECT imaging. The committee agreed that baseline ultrasonography was accurate at 75% compared to CECT in 12 out of 16 patients, while contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) was accurate at 93.8% (15/16). When comparing low (p = 0.0029) and high MI phase-inversion (p = 0.0004) and destructive (p = 0.0015) CEUS imaging to baseline ultrasonography, there was a significant improvement in lesion conspicuity. At greater Sonazoid doses, artifacts were observed; no adverse effects were reported. | |||

| Hiroyoshi et al., 2021 [41] | Japan | Prospective study | 70 | 11/6 | This prospective study aimed to assess CE-IOUS’s effectiveness in predicting Glisson’s capsule invasion during hepatectomy for CLM based on the three parameters listed above. | Colorectal liver metastasis | 24 | CT and EOB-MRI | Pathological tests revealed Glisson invasion in 24 (13%) of the 187 CLMs removed. In three tumors (1.6%), peripheral dilatation was seen by IOUS; in four tumors (2.1%), border irregularity and/or caliber change were found in twenty-four tumors (12.8%). Preoperative EOB-MRI revealed Glisson invasion in only four tumors (sensitivity/specificity, 17%/100%). However, IOUS had a 79% and 96% sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing Glisson invasion with any of the three findings mentioned above. By using receiver operating characteristic analysis, the cutoff value of caliber change for the diagnosis of Glisson invasion was established at 140%. There was no significant difference in the R0 resection rates between patients who had Glisson invasion (85%) and those who did not (82%). |

| Itabashi et al., 2013 [43] | Japan | Prospective study | 64.5 | 41/30 | The study aimed to evaluate the clinical value of Sonazoid-enhanced intraoperative laparoscopic ultrasonography (S-IOLUS) in patients undergoing laparoscopy-assisted colectomy (LAC) for colorectal cancer. This approach addresses the limitations of the conventional palpation and observation of the liver during LAC. | Colorectal cancer | Preoperative imaging, CE-CT, and/or MRI | S-IOLUS (n = 71) found minor hypoechoic lesions in the Kupffer-phase image of two individuals, despite IOLUS not finding any lesions (2.8%). Within six months following LAC, none of the 71 patients who had S-IOLUS revealed liver metastases. Two patients (2.6%) in the traditional IOLUS group (n = 77) had metastatic lesions found in them. Six months following LAC, the two patients’ fresh liver metastases were found. The new liver metastases in these two patients were detected within 6 months after LAC. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elgenidy, A.; Saad, K.; Ibrahim, R.; Sherif, A.; Elmozugi, T.; Darwish, M.Y.; Abbas, M.; Othman, Y.A.; Elshimy, A.; Sheir, A.M.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Sonazoid-Enhanced Ultrasonography for Detection of Liver Metastasis. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020042

Elgenidy A, Saad K, Ibrahim R, Sherif A, Elmozugi T, Darwish MY, Abbas M, Othman YA, Elshimy A, Sheir AM, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Sonazoid-Enhanced Ultrasonography for Detection of Liver Metastasis. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020042

Chicago/Turabian StyleElgenidy, Anas, Khaled Saad, Reda Ibrahim, Aya Sherif, Taher Elmozugi, Moaz Y. Darwish, Mahmoud Abbas, Yousif A. Othman, Abdelrahman Elshimy, Alyaa M. Sheir, and et al. 2025. "Diagnostic Accuracy of Sonazoid-Enhanced Ultrasonography for Detection of Liver Metastasis" Medical Sciences 13, no. 2: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020042

APA StyleElgenidy, A., Saad, K., Ibrahim, R., Sherif, A., Elmozugi, T., Darwish, M. Y., Abbas, M., Othman, Y. A., Elshimy, A., Sheir, A. M., Khattab, D. H., Helal, A. A., Tawadros, M. M., Abuel-naga, O., Abdel-Rahman, H. I., Gamal, D. A., Elhoufey, A., Dailah, H. G., Metwally, R. A., ... Serhan, H. A. (2025). Diagnostic Accuracy of Sonazoid-Enhanced Ultrasonography for Detection of Liver Metastasis. Medical Sciences, 13(2), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020042