An Unusual Case of Nephrotic Range Proteinuria in a Short-Standing Type 1 Diabetic Patient with Newly Diagnosed Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

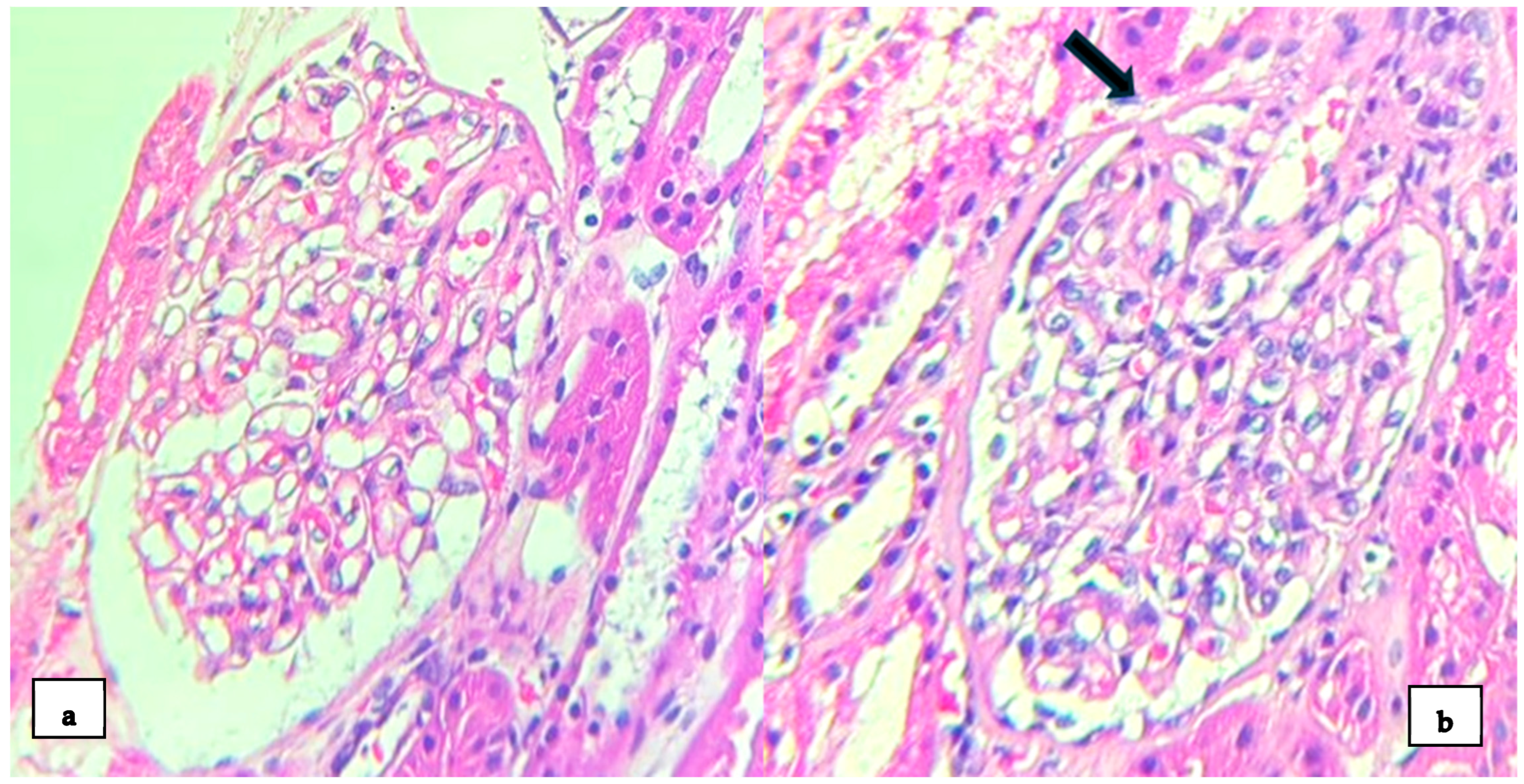

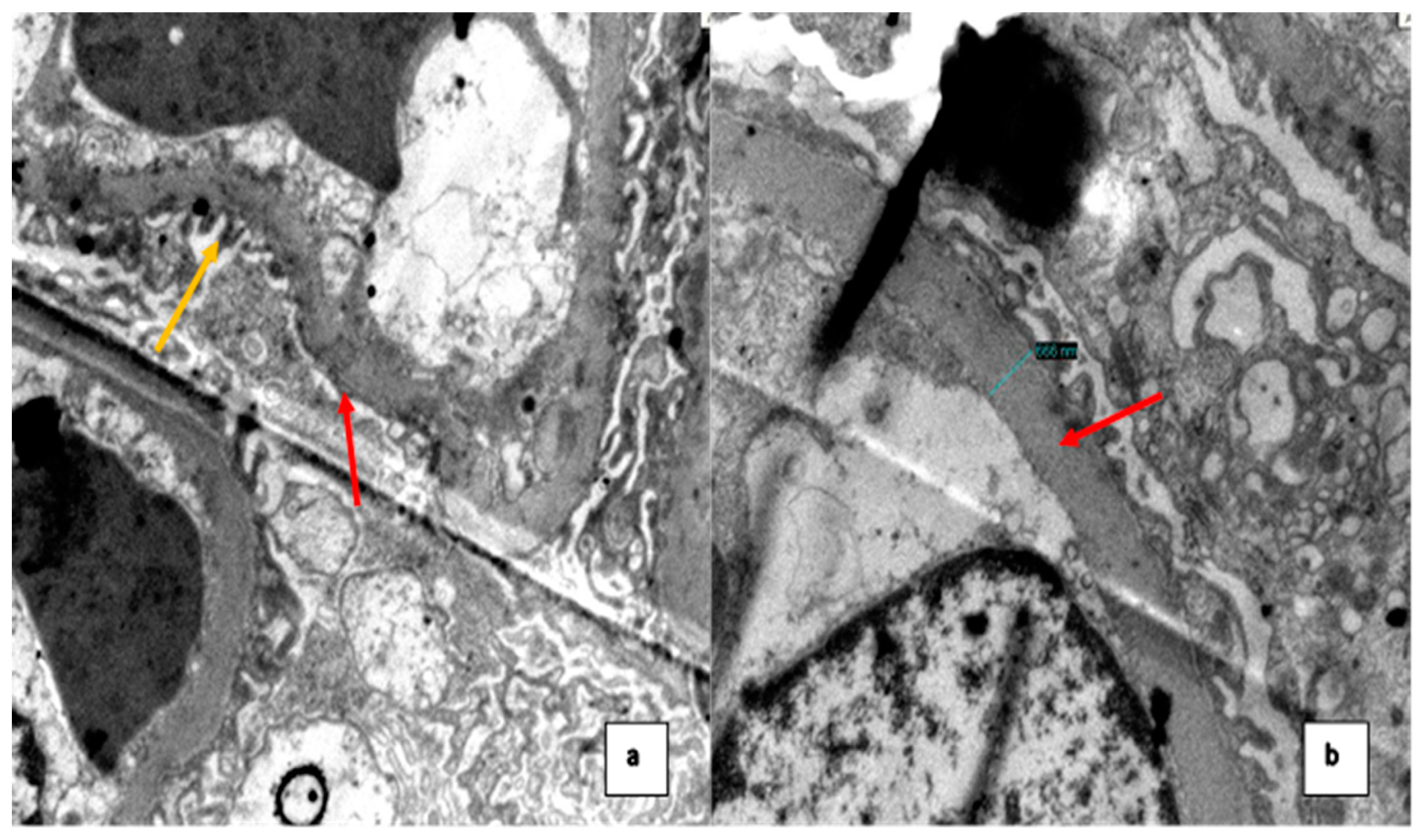

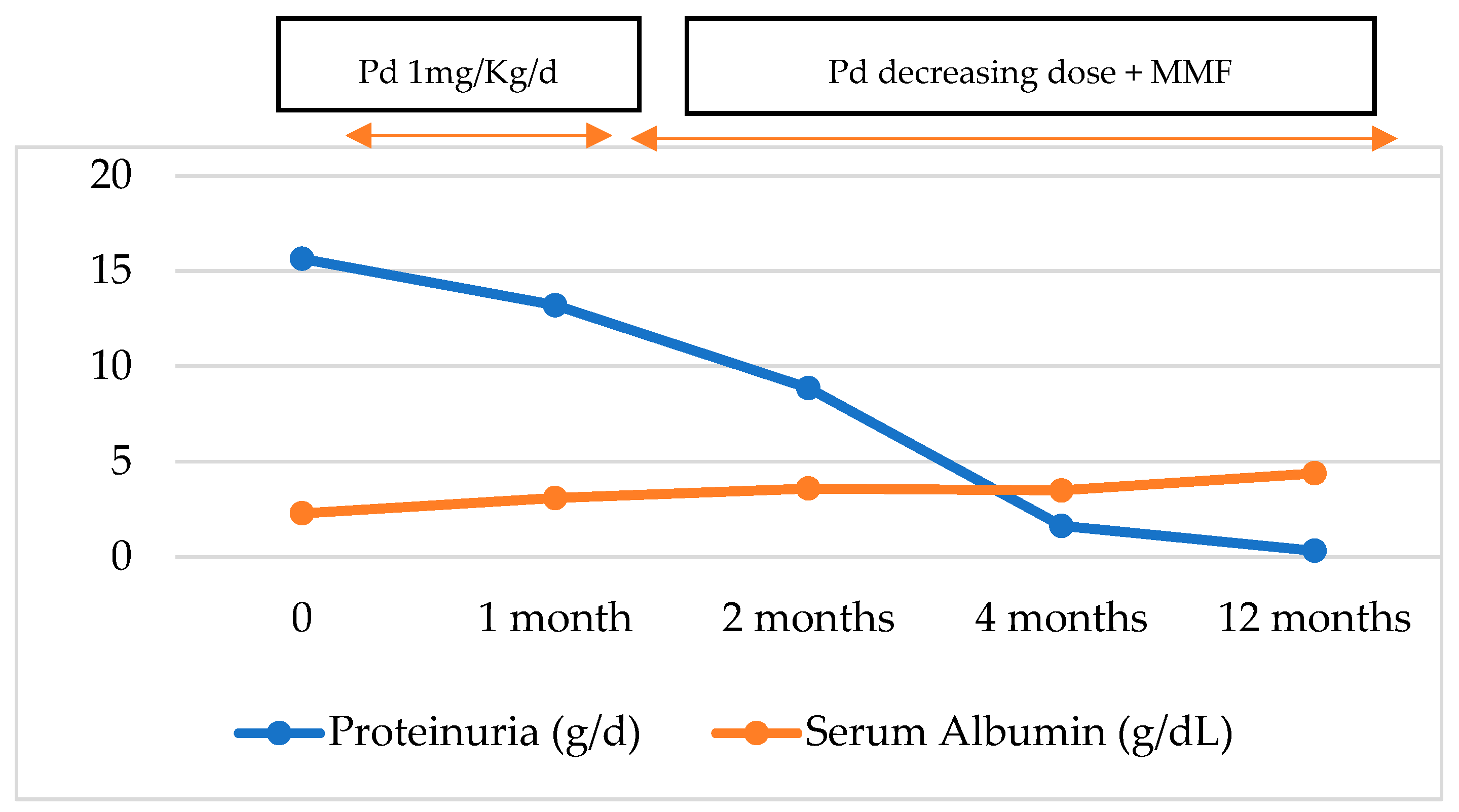

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aringer, M.; Costenbader, K.; Daikh, D.; Brinks, R.; Mosca, M.; Ramsey-Goldman, R.; Smolen, J.S.; Wofsy, D.; Boumpas, D.T.; Kamen, D.L.; et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 1400–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugarte-Gil, M.F.; Alarcón, G.S. Systemic lupus erythematosus in Latin America: Outcomes and therapeutic challenges. Clin. Immunol. Commun. 2023, 4, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, S.V.; Almaani, S.; Brodsky, S.; Rovin, B.H. Update on Lupus Nephritis: Core Curriculum 2020. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 76, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weening, J.J.; D’agati, V.D.; Schwartz, M.M.; Seshan, S.V.; Alpers, C.E.; Appel, G.B.; Balow, J.E.; Bruijn, J.A.N.A.; Cook, T.; Ferrario, F.; et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Damaso, N.; Payan, J.; Oliva-Damaso, E.; Pereda, T.; Bomback, A.S. Lupus Podocytopathy: An Overview. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019, 26, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, P.J.; Costenbader, K.H. Insights into the epidemiology and management of lupus nephritis from the US rheumatologist’s perspective. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.J. Lupus Podocytopathy. In Lupus Nephritis, 2nd ed.; Lewis, E.J., Schwartz, M.M., Korbet, S.M., Chan, D.T.M., Eds.; Oxford Clinical Nephrology Series; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bomback, A.S.; Markowitz, G.S. Lupus Podocytopathy: A Distinct Entity. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z. Clinical-Morphological Features and Outcomes of Lupus Podocytopathy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipino, A.S.; Segretti, P.M.; Ribeiro, B.S.; Gomes, G.M.; de Segura, J.A.; Giovanni Filho, S.C.F.; Zanuto, A.C.D. WCN24-2512 Lupus podocytopathy: Case report. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9 (Suppl. S4), S519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, S.W.; Schwartz, M.M.; Korbet, S.M.; Lewis, E.J. Glomerular podocytopathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.M.; Cooper, M.E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 137–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hünemörder, S.; Treder, J.; Ahrens, S.; Schumacher, V.; Paust, H.; Menter, T.; Matthys, P.; Kamradt, T.; Meyer-Schwesinger, C.; Panzer, U.; et al. TH1 and TH17 cells promote crescent formation in experimental autoimmune glomerulonephritis. J. Pathol. 2015, 237, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paquissi, F.C.; Abensur, H. The Th17/IL-17 axis and kidney diseases, with focus on lupus nephritis. Front. Med. Nephrol. 2021, 8, 654912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, F.; Song, D.; Wang, S.-X.; Zhao, M.-H. Podocyte involvement in lupus nephritis based on the 2003 ISN/RPS system: A large cohort study from a single centre. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, M.; Cobbs, J.; Navarrete, J. Lupus Podocytopathy Case Series in an Urban USA Population. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2019, 73, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, S.P.; Barisoni, L.M.C.; Herzenberg, A.M.; Chander, P.N.; Nickeleit, V.; Seshan, S.V. Collapsing glomerulopathy in 19 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus or lupus-like disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, D.L.; Bembry, W.; Mesa, C.J.; Patel, N.J.; Guevara, M.E. Lupus podocytopathy: Case series and review. Lupus 2022, 31, 1017–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dina-Batlle, L.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Bencosme, E. Lupus podocytopathy: Case series of 4 cases from Dominican Republic. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9 (Suppl. S4), S164–S165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicic, R.Z.; Rooney, M.T.; Tuttle, K.R. Diabetic Kidney Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Franceschini, N.; Hogan, S.; Holder, S.T.; Jennette, C.; Falk, R.; Jennette, J. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis pathologic variants. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, G.K.; Markowitz, G.S.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Appel, G.B.; D’Agati, V.D. Minimal change disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Nephrol. 2002, 57, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rivera, J.E.; García-Carro, C.; Ávila, A.I.; Espino, M.; Espinosa, M.; Fernández-Juárez, G.; Fulladosa, X.; Goicoechea, M.; Macía, M.; Morales, E.; et al. Consensus document of the Spanish Group for the Study of the Glomerular Diseases (GLOSEN) for the diagnosis and treatment of lupus nephritis. Nefrologia Engl. Ed. 2023, 43, 6–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovin, B.H.; Ayoub, I.M.; Chan, T.M.; Liu, Z.H.; Mejía-Vilet, J.M.; Floege, J. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Lupus Nephritis Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of LUPUS NEPHRITIS. Kidney Int. 2024, 105 (Suppl. S1), S1–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A.; Ginzler, E.M.; Gibson, K.; Satirapoj, B.; Santillán, A.E.Z.; Levchenko, O.; Navarra, S.; Atsumi, T.; Yasuda, S.; Chavez-Perez, N.N.; et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term voclosporin treatment for lupus nephritis in the phase 3 AURORA 2 clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Values | Normal Range United | |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 6.8 | 11–15 g/dL |

| Reticulocytes | 21.4% | 0.5–2% |

| Platelet count | 266 | 150–400 × 103 µL |

| White blood cells (WBC) | 13.7 | 5–10 × 103 µL |

| Limphocytes | 3.1 | 1.5–3.5 × 103 µL |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 244 | 120–246 U/L |

| Direct Coombs test | +++ | NA |

| Total bilirrubin | 1.3 | 0.2–1.3 mg/dL |

| Indirect bilirrubin | 0.2 | 0–1.1 mg/dL |

| Total proteins | 5.5 | 6.3–8.2 g/dL |

| Serum albumin | 2.3 | 3.5–5 g/dL |

| Glucose | 305 | 75–110 mg/dL |

| Urea | 16 | 15–36 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.37 | 0.7–1.2 mg/dL |

| Sodium | 131 | 135–148 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 3.7 | 3.5–5.3 mmol/L |

| Total calcium | 8.2 | 8.4–10.2 mg/dL |

| Phosphorus | 4.9 | 2.5–4.5 mg/dL |

| Magnesium | 1.7 | 1.6–2.3 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol | 362 | 0–200 mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | 176 | <150 mg/dL |

| LDL | 244.8 | 0–130 mg/dL |

| AST | 28 | 15–46 U/L |

| ALT | 23 | 13–69 U/L |

| ESR | 140 | 0–15 mm/h |

| CRP | Negative | mg/L |

| Hematuria | 0–2 xc | NA |

| Anti-VHB core | Not Reactive | NA |

| HBsAg | Not Reactive | NA |

| Anti-VHC | Not Reactive | NA |

| Anti-VIH 1-2 | Not Reactive | NA |

| RPR | Not Reactive | NA |

| Anti-HTLV 1-2 | Not Reactive | NA |

| Bengal rose test | Negative | NA |

| Blood culture | Negative | NA |

| Urine culture | Negative | NA |

| Parasitolgy stool | Negative | NA |

| 24 h urine total protein Excretion | 15,640 | 42–225 mg/24 h |

| ANA | 1/800 | NA |

| Anti-dsDNA | ||

| C3 | 103 | 90–180 mg/dL |

| C4 | 9 | 10–40 mg/dL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dominguez Davalos, M.; De La Flor, J.C.; Bedia Castillo, C.; Lipa Chancolla, R.; Rodríguez Tudero, C.; Apaza, J.; Zamora, R.; Cieza-Terrones, M. An Unusual Case of Nephrotic Range Proteinuria in a Short-Standing Type 1 Diabetic Patient with Newly Diagnosed Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Report and Literature Review. Med. Sci. 2024, 12, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci12040074

Dominguez Davalos M, De La Flor JC, Bedia Castillo C, Lipa Chancolla R, Rodríguez Tudero C, Apaza J, Zamora R, Cieza-Terrones M. An Unusual Case of Nephrotic Range Proteinuria in a Short-Standing Type 1 Diabetic Patient with Newly Diagnosed Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Report and Literature Review. Medical Sciences. 2024; 12(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci12040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleDominguez Davalos, Marco, José C. De La Flor, Carlos Bedia Castillo, Roxana Lipa Chancolla, Celia Rodríguez Tudero, Jacqueline Apaza, Rocío Zamora, and Michael Cieza-Terrones. 2024. "An Unusual Case of Nephrotic Range Proteinuria in a Short-Standing Type 1 Diabetic Patient with Newly Diagnosed Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Report and Literature Review" Medical Sciences 12, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci12040074

APA StyleDominguez Davalos, M., De La Flor, J. C., Bedia Castillo, C., Lipa Chancolla, R., Rodríguez Tudero, C., Apaza, J., Zamora, R., & Cieza-Terrones, M. (2024). An Unusual Case of Nephrotic Range Proteinuria in a Short-Standing Type 1 Diabetic Patient with Newly Diagnosed Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Report and Literature Review. Medical Sciences, 12(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci12040074