Investigation of the Effect of Debris-Induced Damage for Constructing Tsunami Fragility Curves for Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Impact from large water-borne objects (e.g., cars, ships, shipping containers, trees, building fragments etc. Figure 2a). A function of debris mass, velocity and contact duration (hardness);

- Increase in flow viscosity/density due to collected smaller debris/sediment (Figure 2b);

- Damming (filling of openings with debris, increasing the effective area experiencing lateral load, Figure 2b).

- Is bias (systematic error) observed in fragility functions which do not explicitly model the presence of debris in tsunami inland flow?

- Can a reliable and accurate estimation of debris effects be incorporated into fragility function derivation?

- What effect does consideration of debris have on financial loss estimation?

2. Proposed Methodology

2.1. Step 1: Exploratory Analysis of Debris-Induced Bias

| Random Component | (1) | ||

| Systematic Component | (2) |

2.2. Step 2: Quantifying the Effect of Debris in Fragility Function Derivation

2.3. Step 3: Quantification of Impact on Financial Loss Estimation

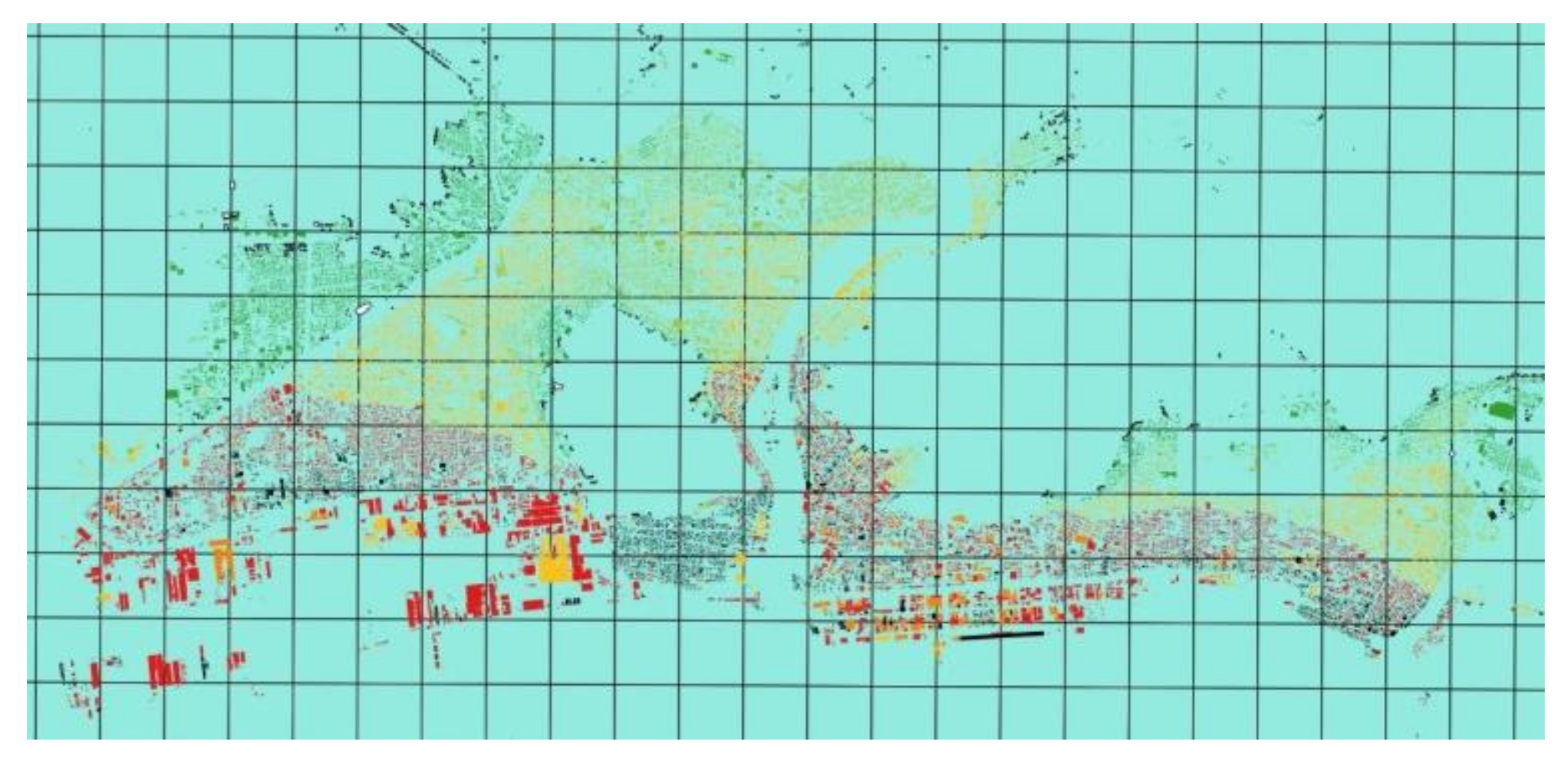

3. Presentation of Case Study Data

3.1. Building Damage Dataset

3.2. Tsunami Inundation Simulation Data

4. Application of Methodology to Case Study Data

4.1. Step 1: Exploratory Analysis of Debris-Induced Bias (Case Study)

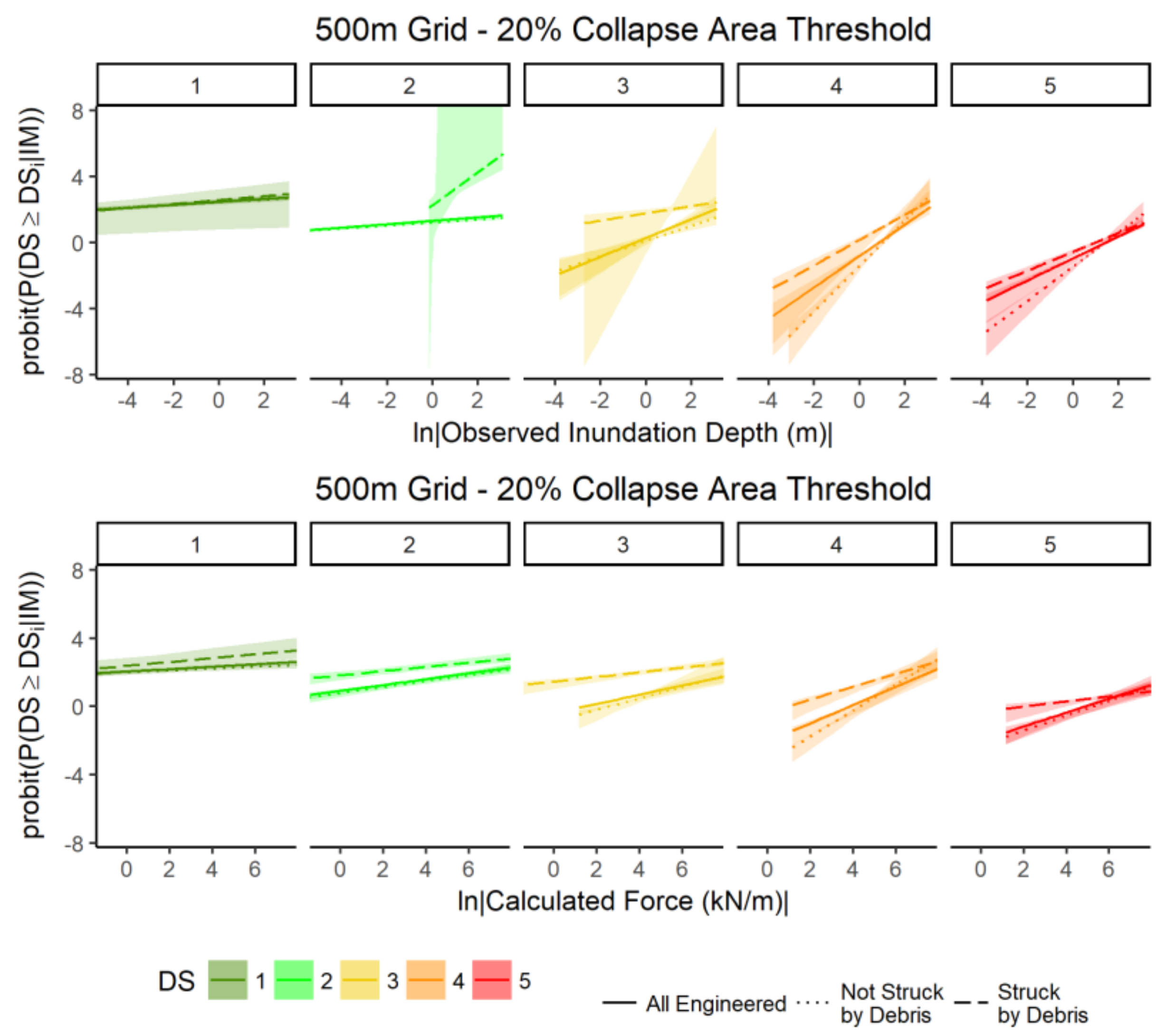

4.2. Step 2: Quantifying the Effect of Debris in Fragility Function Derivation (Case Study)

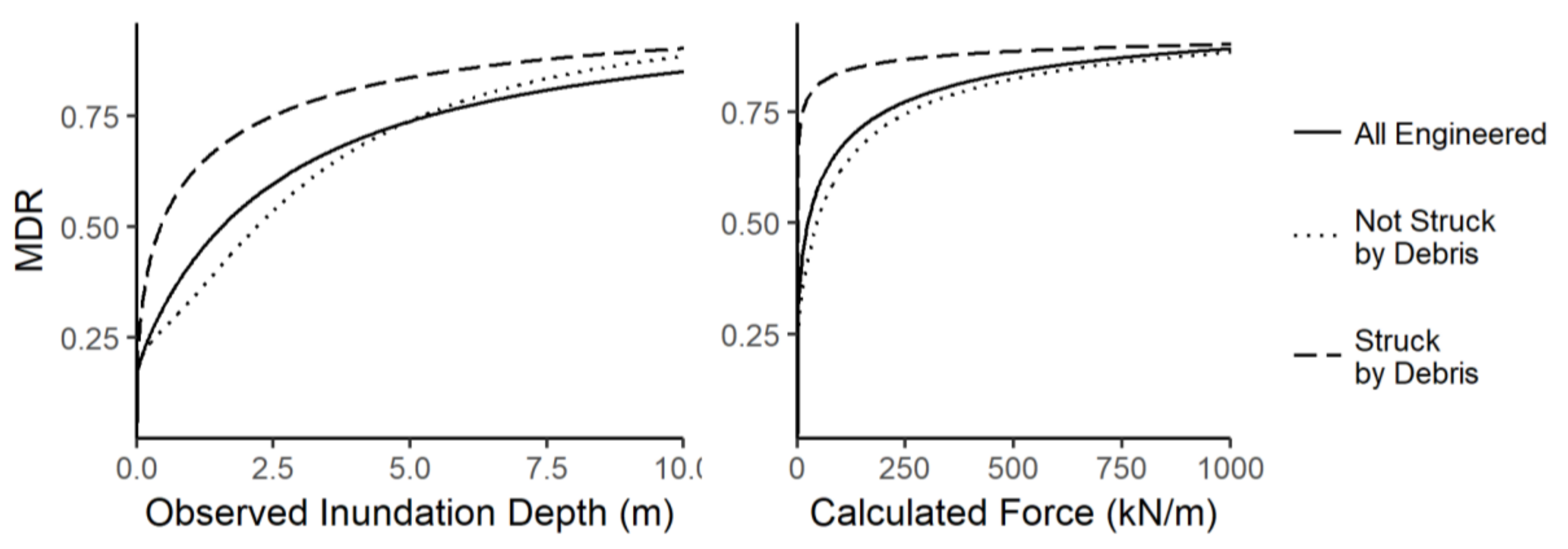

4.3. Step 3: Quantification of Impact on Financial Loss Estimation (Case Study)

5. Conclusions

- Debris-affected buildings mostly experienced higher TIM values and higher damage states (i.e., debris designation occurs in the vicinity of other ‘washed away’ buildings, which as more likely to occur in locations of high TIM values).

- The removal of buildings thought to be affected by debris resulted in changes to both the slope and intercept of the fragility functions. This indicates that the inclusion of debris-damaged buildings in the dataset does have an effect on fragility functions that may not be captured by purely flow regime-related TIMs.

- The difference between the intercept and slope for fluid-only and debris-influenced fragility functions can be quantified by inclusion of debris-indicator terms in the fragility functions.

- The influence of debris regression parameters on determining building damage is shown to be significant for all but the lowest damage state (“minor damage”), for the dataset used.

- More complex fragility functions which incorporate debris regression parameters are shown to have a statistically significant better fit to the observed damage data than models which omit debris information. This suggests that inclusion of debris information in fragility functions improves the accuracy of the model.

- Comparing simulated economic loss for estimates from vulnerability functions which do and do not incorporate a debris term suggests that biases in loss estimation may be introduced if not explicitly modelling debris.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charvet, I.; Macabuag, J.; Rossetto, T. Estimating Tsunami-Induced Building Damage Through Fragility Functions: Critical Review and Research Needs. Front. Built Environ. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarbotton, C.; Dall’Osso, F.; Dominey-Howes, D.; Goff, J. The use of empirical vulnerability functions to assess the response of buildings to tsunami impact: Comparative review and summary of best practice. Earth Sci. Rev. 2015, 142, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

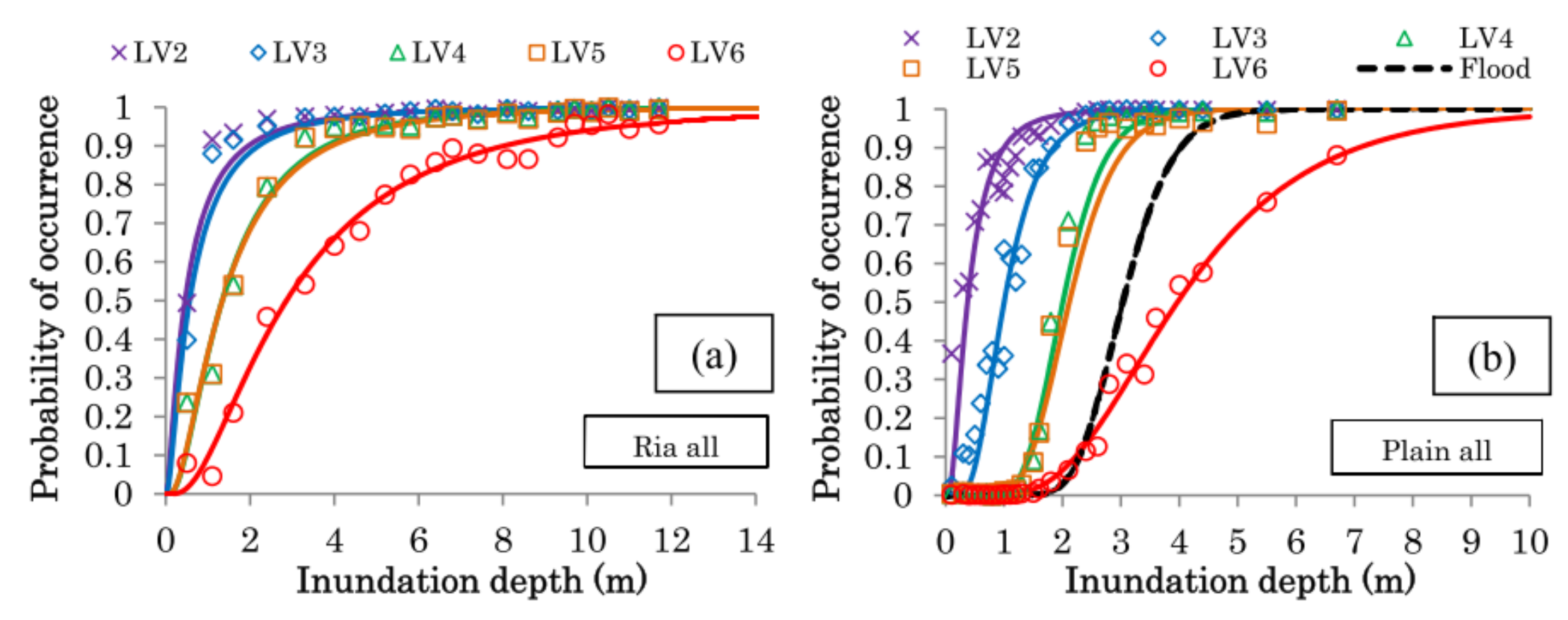

- Suppasri, A.; Charvet, I.; Imai, K.; Imamura, F. Fragility curves based on data from the 2011 Great East Japan tsunami in Ishinomaki city with discussion of parameters influencing building damage. Earthq. Spectra 2014, 31, 841–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earthquake Engineering Field Investigation Team (EEFIT). Field Report: Earthquake and Tsunami of 11th March 2011. Available online: https://www.istructe.org/getattachment/resources-centre/technical-topic-areas/eefit/eefit-reports/EEFIT-Japan-Recovery-Return-Mission-2013-Report-(1).pdf.aspx (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Koshimura, S.; Namegaya, Y.; Yanagisawa, H. Tsunami Fragility — A New Measure to Identify Tsunami Damage. J. Disaster Res. 2009, 4, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvet, I.; Suppasri, A.; Imamura, F. Empirical fragility analysis of building damage caused by the 2011 Great East Japan tsunami in Ishinomaki city using ordinal regression, and influence of key geographical features. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 28, 1853–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, N.; Onai, A.; Kondo, K. Fragility curve of region of wooden building washout due to tsunami based on hydrodynamic characteristics of the Great East Japan Tsunami. Ocean Eng. 2015, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macabuag, J.; Rossetto, T.; Ioannou, I.; Suppasri, A.; Sugawara, D.; Adriano, B.; Imamura, F.; Eames, I.; Koshimura, S. A proposed methodology for deriving tsunami fragility functions for buildings using optimum intensity measures. Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 1257–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvet, I.; Suppasri, A.; Kimura, H.; Sugawara, D.; Imamura, F. Fragility estimations for Kesennuma City following the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami based on maximum flow depths, velocities and debris impact, with evaluation of the ordinal model’s predictive accuracy. Nat. Hazards 2015, 79, 2073–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macabuag, J.; Rossetto, T.; Ioannou, I. Investigation of the Effect of Debris-Induced Damage for Constructing Tsunami Fragility Curves for Buildings. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Natural Hazards & Infrastructure, Crete, Greece, 28–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetto, T.; Ioannou, I.; Grant, D.N.; Maqsood, T. Guidelines for Empirical Vulnerability Assessment. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tiziana_Rossetto/publication/265300146_Guidelines_for_empirical_vulnerability_assessment/links/561e71f608ae50795afefafc/Guidelines-for-empirical-vulnerability-assessment.pdf 2014 (accessed on 14 March 2018).

- Charvet, I.; Ioannou, I.; Rossetto, T.; Suppasri, A.; Imamura, F. Empirical fragility assessment of buildings affected by the 2011 Great East Japan tsunami using improved statistical models. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 951–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhari, A.; Charvet, I.; Tsuyoshi, F.; Suppasri, A.; Imamura, F. Assessment of tsunami hazards in ports and their impact on marine vessels derived from tsunami models and the observed damage data. Nat. Hazards 2015, 78, 1309–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Japan Cabinet Office. Residential Disaster Damage Accreditation Criteria Operational Guideline. Available online: http://www.bousai.go.jp/taisaku/unyou.html (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Suppasri, A.; Mas, E.; Koshimura, S.; Imai, K.; Harada, K.; Imamura, F. Developing Tsunami Fragility Curves From the Surveyed Data of the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami in Sendai and Ishinomaki Plains. Coast. Eng. J. 2012, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppasri, A.; Mas, E.; Charvet, I.; Gunasekera, R.; Imai, K.; Fukutani, Y.; Abe, Y.; Imamura, F. Building damage characteristics based on surveyed data and fragility curves of the 2011 Great East Japan tsunami. Nat. Hazards 2013, 66, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.X.; Eames, I.; Johnson, E.R. Force acting on a square cylinder fixed in a free-surface channel flow. J. Fluid Mech. 2014, 756, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.S.J.; Rossetto, T.; Allsop, W. An experimentally validated approach for evaluating tsunami inundation forces on rectangular buildings. Coast. Eng. 2017, 128, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriano, B.; Koshimura, S.; Hayashi, S.; Gokon, H.; Mas, E. Understanding the extreme tsunami inundation in onagawa town by the 2011 tohoku earthquake, its effects in urban structures and coastal facilities. Coast. Eng. J. 2016, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, K.; Fujii, Y.; Harada, T.; Namegaya, Y. Time and Space Distribution of Coseismic Slip of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake as Inferred from Tsunami Waveform Data. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2013, 103, 1473–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; Gica, E.; Takahashi, T.; Shuto, N. Numerical Simulation of the 1992 Flores Tsunami: Interpretation of Tsunami Phenomena in Northeastern Flores Island and Damage at Babi Island. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1995, 144, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Risi, R.; Goda, K.; Mori, N.; Yasuda, T. Bayesian tsunami fragility modeling considering input data uncertainty. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2017, 31, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MLIT). Survey of Tsunami Damage Conditions; MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2014.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MLIT). National Statistics; MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2015.

- Construction Research Institute (CRI). Japan Building Cost Information; CRI: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; p. 547. [Google Scholar]

| Damage State | Description | Use | Image | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | Minor Damage | Inundation below ground floor. | Possible to use immediately after minor floor and wall cleanup. |  | |

| DS2 | Moderate Damage | The building is inundated less than 1m above the floor. | Possible to use after moderate repairs. |  | |

| DS3 | Major Damage | The building is inundated more than 1m above the floor (below the ceiling) | Possible to use after major repairs. |  | |

| DS4 | Complete Damage | The building is inundated above the ground floor level. | Major work is required for re-use of the building. |  | |

| DS5* | DS5 | Collapsed | The key structure is damaged, and difficult to repair to be used as it was before | Not repairable. |  |

| DS6 | Washed Away | The building is completely washed away except for the foundation | Not repairable. |  | |

| Threshold | Number of Buildings Designated as Affected by Debris | % of total Dataset (4570 Buildings) Affected by Debris |

|---|---|---|

| Base case (no buildings designated as having been affected by debris) | 0 | 0% |

| 50% of total grid building area | 588 | 13% |

| 35% of total grid building area | 778 | 17% |

| 20% of total grid building area | 1440 | 32% |

| Parameter | Parameter Description | Estimate | Std. Error | p | Significance 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β0 | 0|1.(Intercept) | 2.44 | 0.08 | 1.14 × 10−189 | *** |

| 1|2.(Intercept) | 1.20 | 0.03 | 5.01 × 10−294 | *** | |

| 2|3.(Intercept) | 0.11 | 0.03 | 2.89 × 10−5 | *** | |

| 3|4.(Intercept) | −1.41 | 0.05 | 1.31 × 10−190 | *** | |

| 4|5.(Intercept) | −1.45 | 0.05 | 2.93 × 10−163 | *** | |

| β1 | 0|1. ln|hobs j| | 0.08 | 0.01 | 2.69 × 10−31 | *** |

| 1|2. ln|hobs j| | 0.09 | 0.01 | 3.38 × 10−52 | *** | |

| 2|3. ln|hobs j| | 0.46 | 0.02 | 1.62 × 10−124 | *** | |

| 3|4. ln|hobs j| | 1.38 | 0.04 | 3.71 × 10−296 | *** | |

| 4|5. ln|hobs j| | 1.03 | 0.04 | 1.72 × 10−119 | *** | |

| β2 | 0|1. debrisj | 0.13 | 0.21 | 5.36 × 10−1 | |

| 1|2. debrisj | 1.06 | 0.15 | 2.83 × 10−12 | *** | |

| 2|3. debrisj | 1.67 | 0.10 | 1.57 × 10−64 | *** | |

| 3|4. debrisj | 1.58 | 0.12 | 2.90 × 10−38 | *** | |

| 4|5. debrisj | 0.89 | 0.11 | 2.37 × 10−15 | *** | |

| β3 | 0|1. ln|hobs j|. debrisj | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.62 × 10−2 | * |

| 1|2 . ln|hobs j|. debrisj | 0.91 | 0.23 | 6.58 × 10−5 | *** | |

| 2|3 . ln|hobs j|. debrisj | −0.24 | 0.04 | 1.74 × 10−8 | *** | |

| 3|4 . ln|hobs j|. debrisj | −0.61 | 0.08 | 1.44 × 10−15 | *** | |

| 4|5 . ln|hobs j|. debrisj | −0.46 | 0.07 | 6.89 × 10−11 | *** |

| Model | Number of Parameters | Akaike Information Criteria Statistic | Log-Likelihood | Pr (>Chisq) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Component | Systematic Component | ||||

| Equation (1) | Equation (2) | 10 | 11,177 | −5578 | |

| Equation (3) | 15 | 10,547 | −5258 | <2.2 × 10−16 *** | |

| Equation (4) | 20 | 10,400 | −5180 | <2.2 × 10−16 *** | |

| Model Number | Model Description | Total Economic Loss (Calculated from Vulnerability Functions with the Following TIMs) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inundation Depth | Force | ||

| (1) | Considering a single TIM only | 4362$M | 4310$M |

| (4) | Considering Debris (and interaction) | 4231$M | 4175$M |

| Difference: | 1.2% | 1.4% | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macabuag, J.; Rossetto, T.; Ioannou, I.; Eames, I. Investigation of the Effect of Debris-Induced Damage for Constructing Tsunami Fragility Curves for Buildings. Geosciences 2018, 8, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8040117

Macabuag J, Rossetto T, Ioannou I, Eames I. Investigation of the Effect of Debris-Induced Damage for Constructing Tsunami Fragility Curves for Buildings. Geosciences. 2018; 8(4):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8040117

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacabuag, Joshua, Tiziana Rossetto, Ioanna Ioannou, and Ian Eames. 2018. "Investigation of the Effect of Debris-Induced Damage for Constructing Tsunami Fragility Curves for Buildings" Geosciences 8, no. 4: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8040117

APA StyleMacabuag, J., Rossetto, T., Ioannou, I., & Eames, I. (2018). Investigation of the Effect of Debris-Induced Damage for Constructing Tsunami Fragility Curves for Buildings. Geosciences, 8(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8040117