Quantitative Examination of Piezoelectric/Seismoelectric Anomalies from Near-Surface Targets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Brief Background

3. Can Piezoelectric and Seismoelectric Effects Be Related to Potential Fields?

4. Short Description of the Interpretation Methodology Developed in Magnetic Prospecting

- (1)

- Thin bed:where Ae is the piezoelectric moment, AT is the total intensity of the piezoelectric (seismoelectric) anomaly, and h is the depth of the upper edge of a thin bed.

- (2)

- (3)

5. Application of the Proposed Methodology: Field Cases

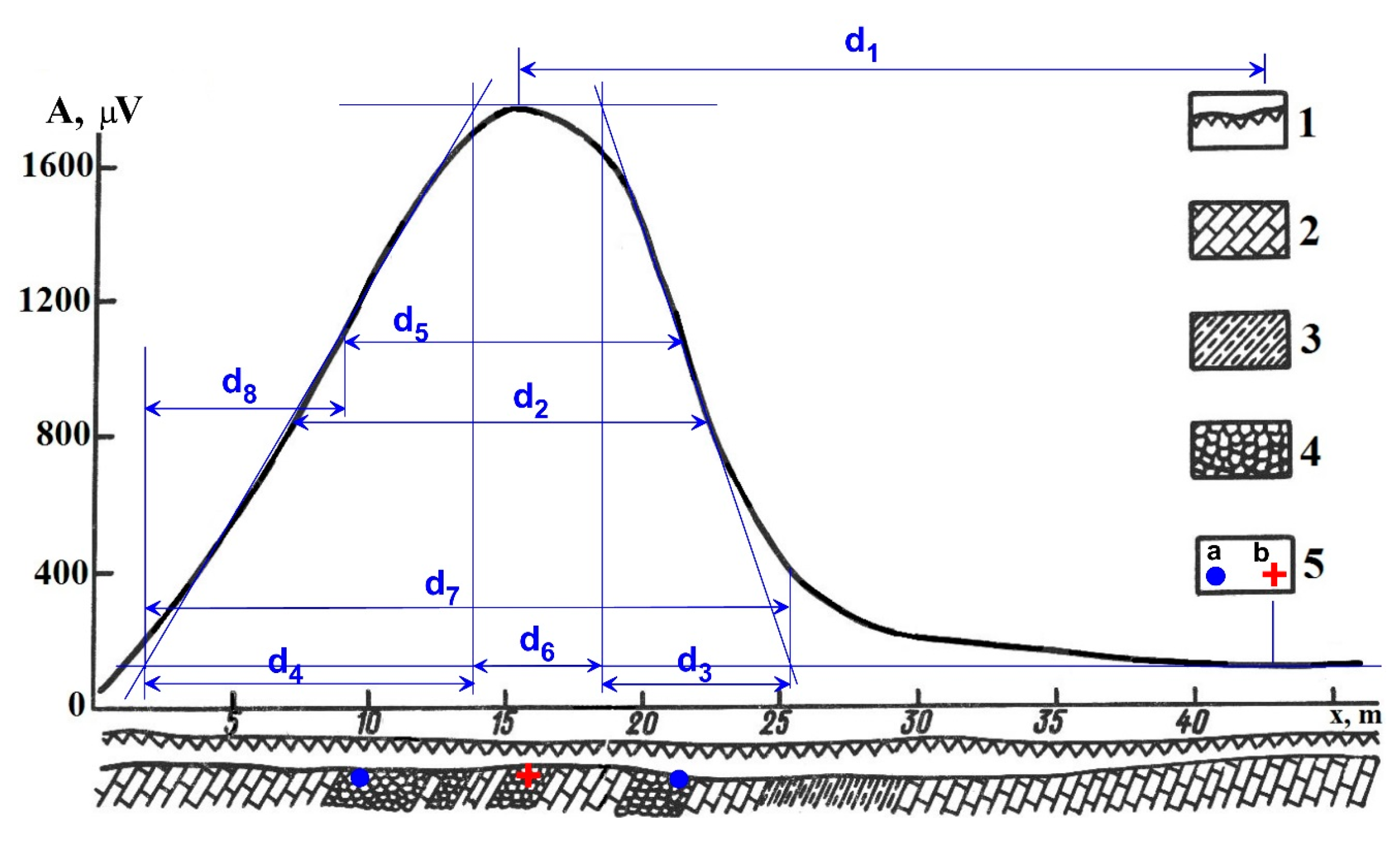

5.1. Employment of the Interpretation Methodology in Ore Geophysics

5.1.1. Gold-Bearing Quartz Deposit Ustnerinskoe (Eastern Yakutia, Russia)

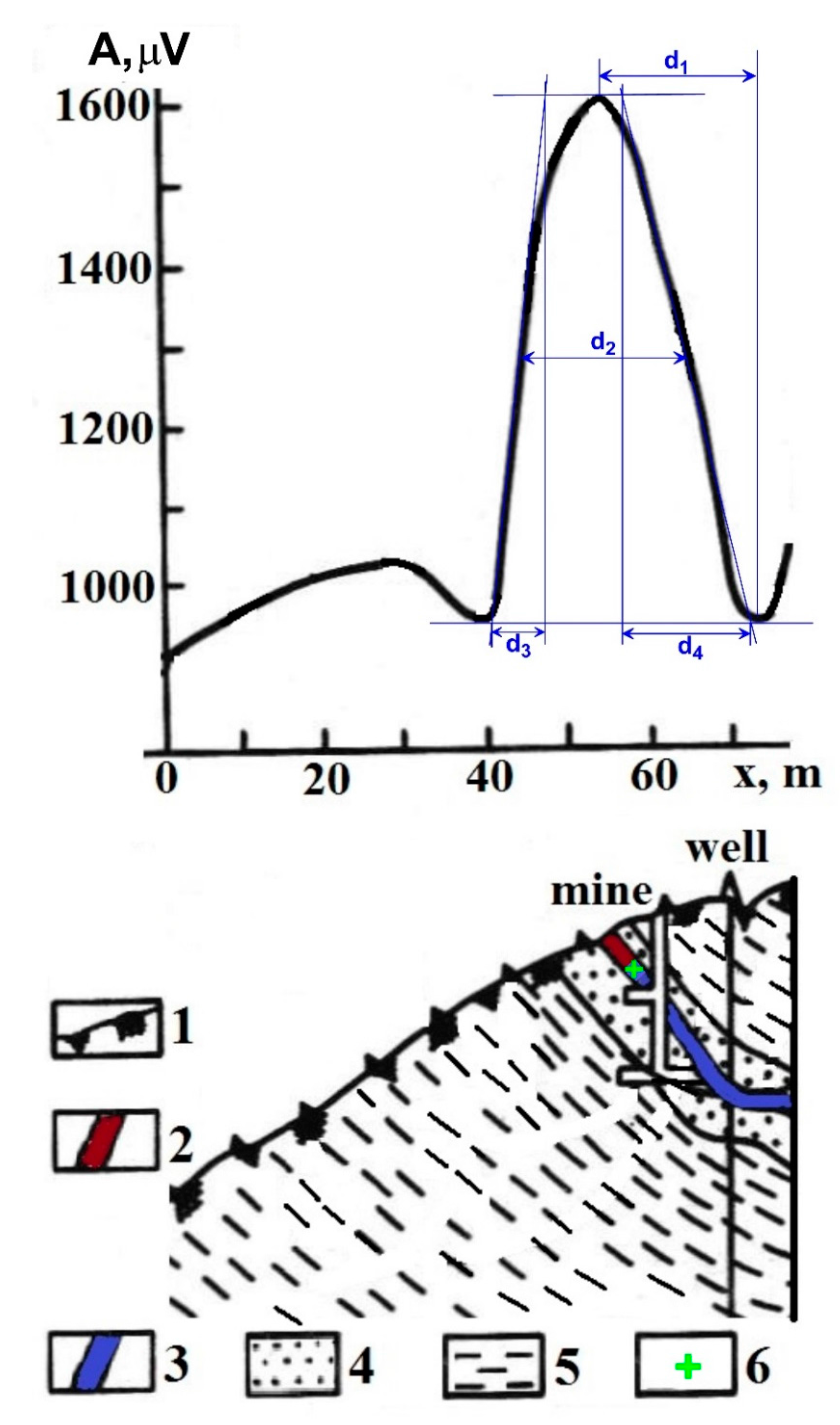

5.1.2. Gold Quartz Deposit (Central Yakutia, Russia)

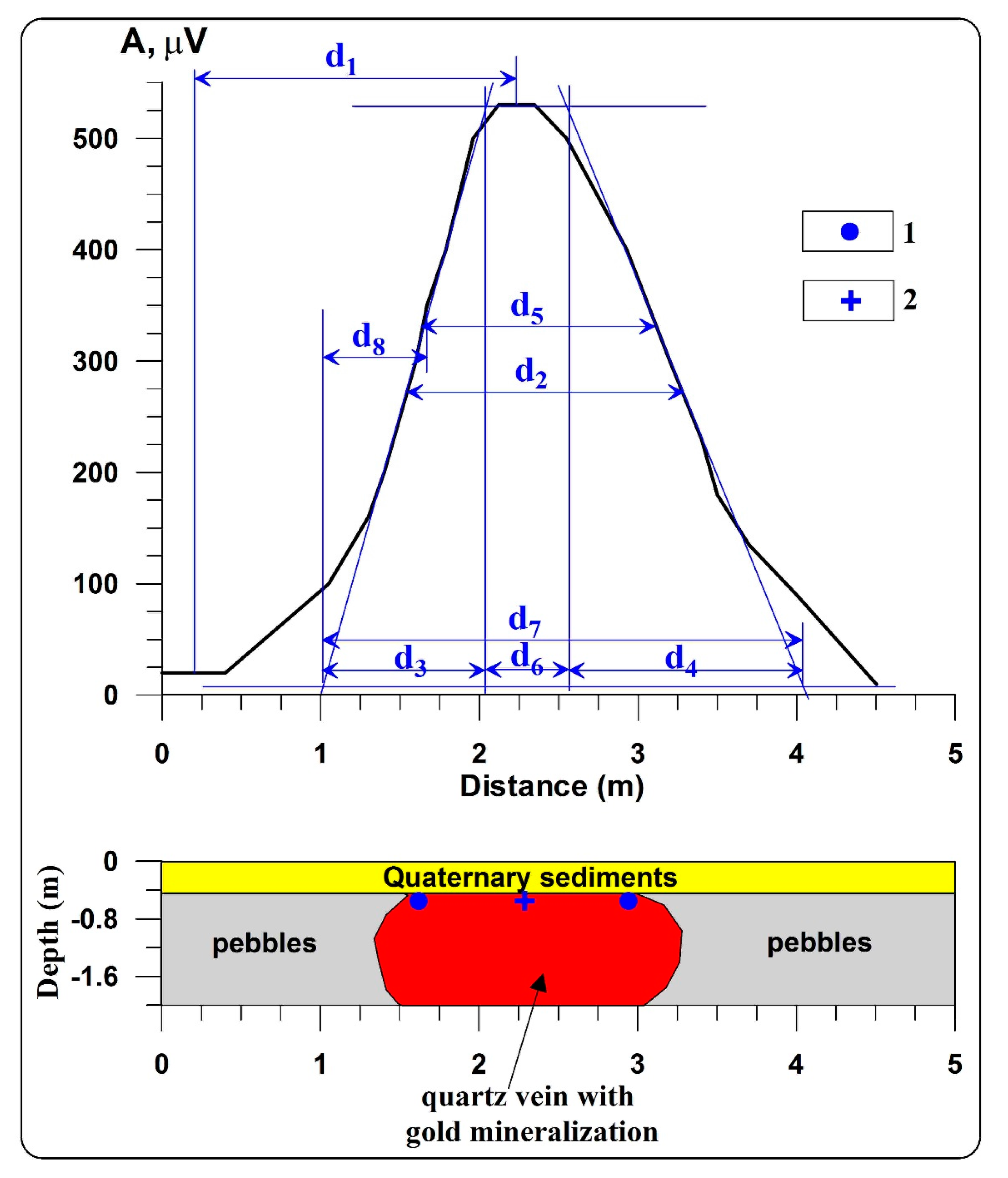

- d1 = distance between the maximum and minimum of the anomaly;

- d2 = distance between the left and right branches at the level of semiamplitude;

- d3 = difference in abscissae of the points of intersection of an inclined tangent with horizontal tangents on one branch;

- d4 = the same on the other branch (d3 is selected from the plot branch with conjugated extremums, d3 ≤ d4), and the x-axis is oriented in this direction);

- d5 = distance between the middle point of the left and right tangents;

- d6 = distance between d3 and d4;

- d7 = d3 + d4 + d6;

- d8 = distance between the ending of parameter d4 and beginning of parameter d5.

5.1.3. Crystal-Quartz Deposit Pilengichey (Subpolar Ural, Russia)

5.2. Case Study at the Archaeological Site Tel Kara Hadid (Southern Israel)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volarovich, M.P.; Parkhomenko, E.I. Piezoelectric effect of rocks. Acad. Sci. USSR Geophys. 1955, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Neishdadt, N.M.; Osipov, L.N. On using of seismoelectric effects of the second type observed by pegmatites searching. Trans. VITR (All-Union Inst. Tech. Prospect. Methods) 1958, 11, 63–71. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Neishdadt, N.M.; Osipov, L.N. Piezoelectric method. In Borehole and Mine Geophysics; Nedra Publisher: Moscow, Russia, 1959; pp. 153–168, 251–256, and 371–372. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Neishtadt, N.M. Searching pegmatites using seismo-electric effect of the second kind. Sov. Geol. 1961, 1, 121–127. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Parkhomenko, E.I. Electrification Phenomena in Rocks; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhomenko, E.I. Main peculiarities of seismoelectric effect of sedimentary rocks and ways of its using in geophysics. In Physical Properties of Rocks and Minerals under High Pressure and Temperature; Nauka Publisher: Moscow, Russia, 1977; pp. 201–208. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashev, S.N. The Piezoelectric Method of Exploration; Nedra, Moscow, Engl. Transl.; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sobolev, G.A.; Demin, V.M.; Narod, B.B.; White, P. Tests of piezoelectric and pulsed-radio methods for quartz vein and base-metal sulfides prospecting at Giant Yellowknife Mine, N.W.T., and Sullivan Mine, Kimberley, Canada. Geophysics 1984, 49, 2178–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neishdadt, N.M.; Mazanova, Z.V.; Suvorov, N.D. The application of piezoelectric method for searching ore-quartz deposits in Yakutia. In Seismic Methods of Studying Complicated Media in Ore Regions; NPO Rudgeofizika: Leningrad, Russia, 1986; pp. 109–116. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, M.; Russel, R.D.; Kepic, A.W.; Butler, K.E. Electromagnetic responses from seismically excited targets: Non-Piezoelectric Phenomena. Explor. Geophys. 1992, 23, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neishtadt, N.M.; Mazanova, Z.V.; Suvorov, V.D.; Popov, A. Technology of the piezoelectric method application in ore-quartz deposits using the Ametist-type station. In Proceedings of the Transaction of SEG-EAGE Moscow Geophysical Conference and Exhibition, Moscow, Russia, 16–19 August 1993; pp. 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, K.E.; Russell, R.D.; Kepic, A.W.; Maxwell, M. Mapping of a Stratigraphic Boundary by its Seismoelectric Response. In Proceedings of the SAGEEP 1994 Conference, Englefield, OH, USA, 27 March 1994; pp. 689–699. [Google Scholar]

- Kepic, A.W.; Maxwell, M.; Russell, R.D. Field trials of a seismoelectric method for detecting massive sulfides. Geophysics 1995, 60, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neishtadt, N.; Eppelbaum, L.; Levitski, A. Application of seismo-electric phenomena in exploration geophysics: Review of Russian and Israeli experience. Geophysics 2006, 71, B41–B53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haartsen, M.W.; Pride, S.R. Electroseismic waves from point sources in layered media. J. Geophys. Res. 1997, 102, 24745–24769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, O.V.; Haarsten, M.W.; Toksoz, N. Electroseismic investigation of the shallow subsurface: Field measurements and numerical modeling. Geophysics 1997, 62, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaoka, H.; Yamanaka, S.; Ikea, M. Measurements of electric potential variation by piezoelectricity of granite. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 2225–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamish, D. Characteristics of near surface electrokinetic coupling. Geophys. J. Int. 1999, 137, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulytchov, A. Seismic-electric effect method on guided and reflected waves. Phys. Chem. Earth Part A Solid Earth Geod. 2000, 25, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neishtadt, N.M. Application of piezoelectric method in ore deposits. In Proceedings of the Transaction of the 15th Conference of Israel Mineral Science and Engineering Association, Jerusalem, Israel, 12–13 April 2000; pp. 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Haartsen, M.W.; Toksöz, M.N. Experimental studies of seismoelectric conversions in fluid-saturated porous media. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2000, 105, 28055–28064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenzon, N.; Bambakidis, G. Modeling of seismo-electromagnetic phenomena. Russ. J. Earth Sci. 2001, 3, 247–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiesseyre, K.P. Anomalous piezoelectric effects found in the laboratory and reconstructed y numerical simulation. Ann. Geophys. 2002, 45, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, K.E.; Russell, R.D. Cancellation of multiple harmonic noise series in geophysical records. Geophysics 2003, 68, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pride, S.R.; Garambois, S. Electroseismic wave theory of Frenkel and more recent developments. J. Eng. Mech. 2005, 131, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, S.S.; Pride, S.R.; Klemperer, S.L.; Biodi, B. Seismoelectric imaging of shallow targets. Geophysics 2007, 72, G9–G20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, J.C.; Butler, K.E.; Kepic, A.W.; Harris, B.D. Anatomy of a seismoelectric conversion: Measurements and conceptual modeling in boreholes penetrating a sandy aquifer. J. Geophysl Res. 2009, 114, B10306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, P.W.J.; Jackson, M.D. Borehole electrokinetics. Lead. Edge 2010, 29, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schakel, M.D.; Smeulders, D.M.J.; Slob, E.C.; Heller, H.K.J. Seismoelectric interface response: Experimental results and forward model. Geophysics 2011, 76, N29–N36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neishtadt, N.M.; Eppelbaum, L.V. Perspectives of application of piezoelectric and seismoelectric methods in applied geophysics. Russ. Geophys. J. 2012, 51, 63–80. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gershenzon, N.I.; Bambakidis, G.; Ternovskiy, I. Coseismic electromagnetic field due to the electrokinetic effect. Geophysics 2014, 79, E217–E229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouniaux, L.; Zyserman, F. A review on electrokinetically induced seismo-electrics, electro-seismics, and seismo-magnetics for Earth sciences. Solid Earth 2016, 7, 249–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrichsberg, D.A. Course of Colloidal Chemistry; Chemistry Publisher: S.-Petersburg, Russia, 1995. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, A.G. The electroseismic effect of the second kind. Izv. Acad. Sci. USSR (Trans. Sov. Acad. Sci.) 1940, 5, 699–727, (In Russian, transl. to English). [Google Scholar]

- Probstein, R.F. Physiochemical Hydrodynamics: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, Y.I. On the theory of seismic and seismoelectric phenomena in a moist soil. Izv. Acad. Sci. USSR 1944, 133–150, (In Russian, transl. to English). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, K.E. Seismoelectric Effects of Electrokinetic Origin. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jardani, A.; Revil, A.; Slob, E.; Söllner, W. Stochastic joint inversion of 2D seismic and seismoelectric signals in linear poroelastic materials: A numerical investigation. Geophysics 2010, 75, N19–N31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahardika, H.; Revil, A. Seismoelectric conversion generated from water-oil boundary in unsaturated porous media. In Proceedings of the Transactions of SEG Meeting, Houston, TX, USA, 22–27 September 2013; pp. 1852–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Antonova, E. Finite Elements for Electrically Unbounded Piezoelectric Vibrations. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jandaghian, A.A.; Jafari, A.A. Investigating the Effect of Piezoelectric layers on Circular Plates under Forced Vibration. Int. J. Adv. Des. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Alperovich, L.S.; Neishtadt, N.M.; Berkovitch, A.L.; Eppelbaum, L.V. Tomography approach and interpretation of the piezoelectric data. In Proceedings of the Transactions of the IX General Assembly of the European Geophysical Society, Strasbourg, France; 1997. 59/4P02. p. 546. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lev_Eppelbaum/publication/240527113_Tomography_approach_and_interpretation_of_the_piezoelectric_data/links/0deec531d5667bc6ab000000.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2017).

- Eppelbaum, L.V.; Itkis, S.E.; Khesin, B.E. Optimization of Magnetic Investigations in the Archaeological Sites in Israel. In Filtering, Modeling and Interpretation of Geophysical Fields at Archaeological Objects; Special Issue of Prospezioni Archeologiche; 2000; pp. 65–92. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250613019_Optimization_of_magnetic_investigations_in_the_archaeological_sites_in_Israel (accessed on 15 September 2017).

- Eppelbaum, L.V.; Khesin, B.E.; Itkis, S.E. Prompt magnetic investigations of archaeological remains in areas of infrastructure development: Israeli experience. Archaeol. Prospect. 2001, 8, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelbaum, L.V.; Khesin, B.E.; Itkis, S.E. Archaeological geophysics in arid environments: Examples from Israel. J. Arid Environ. 2010, 74, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelbaum, L.V. Archaeological geophysics in Israel: Past, Present and Future. Adv. Geosci. 2010, 24, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelbaum, L.V. Study of magnetic anomalies over archaeological targets in urban conditions. Phys. Chem. Earth 2011, 36, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelbaum, L.V. Quantitative interpretation of magnetic anomalies from thick bed, horizontal plate and intermediate models under complex physical-geological environments in archaeological prospection. Archaeol. Prospect. 2015, 23, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelbaum, L.V. Quantitative Analysis of Piezoelectric and Seismoelectric Anomalies in Subsurface Geophysics. In Proceedings of the Transactions of the 13th EUG Meeting Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 April 2017; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Eppelbaum, L.V.; Mishne, A.R. Unmanned Airborne Magnetic and VLF investigations: Effective Geophysical Methodology of the Near Future. Positioning 2011, 2, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelbaum, L.V. Geophysical observations at archaeological sites: Estimating informational content. Archaeol. Prospect. 2014, 21, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelbaum, L.V.; Alperovich, L.; Zheludev, V.; Pechersky, A. Application of informational and wavelet approaches for integrated processing of geophysical data in complex environments. In Proceedings of the 2011 SAGEEP Conference, Charleston, SC, USA, 10–14 April 2011; pp. 24–60. [Google Scholar]

| Piezoactivity Group | Rock/Ore/Mineral | Dmin–Dmax | Daver |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Quartz-tourmaline-cassiterite ore | 0.8–28.0 | 15.7 |

| Antimonite-quartz ore | 0.2–1.35 | 0.6 | |

| Apatite-nepheline ore | 0–5.0 | 0.9 | |

| Galenite-sphalerite ore | 0.2–7.7 | 3.3 | |

| Ijolite | 0.1–8 | 1.3 | |

| II | Melteigite | 0.2–5.0 | 1.6 |

| Pegmatite | 0.1–4.8 | 1.3 | |

| Skarn with galenite-sphalerite mineralization | 0.1–3.0 | 0.6 | |

| Sphalerite-galenite ore | 0.3–7.7 | 3.8 | |

| Turjaite | 0.9–4.8 | 2.2 | |

| Urtite | 0.1–32.5 | 3.4 | |

| Juvite | 0.2–5.4 | 1.8 | |

| III | Aleurolite silicificated | 0–0.5 | 0.2 |

| Aplite | 0–1.7 | 0.6 | |

| Breccia aleurolite-quartz | 0.1–0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Gneiss | 0–1.4 | 0.3 | |

| Granite | 0–1.6 | 0.4 | |

| Granodiorite | 0–0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Quartzite | 0–3.3 | 0.6 | |

| Pegmatite ceramic | 0–1.0 | 0.1 | |

| Sandstone silicificated and tourmalinised | 0.1–1.4 | 0.5 | |

| Feldspars | 0–0.4 | 0.15 | |

| Porphyrite | 0–0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Ristschorrite | 0.3–0.9 | 0.5 | |

| Schist argillaceous | 0–0.6 | 0.1 | |

| Hornfels | 0–0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Skarn sphaleritic-garnet | 0–1 | 0.3 | |

| Skarn pyroxene-garnet | 0–0.2 | 0.1 | |

| IV | Aleurolite, amphibolites, andesite, gabbro, greisens, diabase, sandstone | 0–0.1 | 0.05 |

| Argillite, beresite, dacite, diorite-porphyrite, felsite-liparite, limestone, tuff, fenite | 0 | 0 |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eppelbaum, L. Quantitative Examination of Piezoelectric/Seismoelectric Anomalies from Near-Surface Targets. Geosciences 2017, 7, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences7030090

Eppelbaum L. Quantitative Examination of Piezoelectric/Seismoelectric Anomalies from Near-Surface Targets. Geosciences. 2017; 7(3):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences7030090

Chicago/Turabian StyleEppelbaum, Lev. 2017. "Quantitative Examination of Piezoelectric/Seismoelectric Anomalies from Near-Surface Targets" Geosciences 7, no. 3: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences7030090

APA StyleEppelbaum, L. (2017). Quantitative Examination of Piezoelectric/Seismoelectric Anomalies from Near-Surface Targets. Geosciences, 7(3), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences7030090