Detecting Anomalies in Radon and Thoron Time Series Data Using Kernel and Wavelet Density Estimation Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

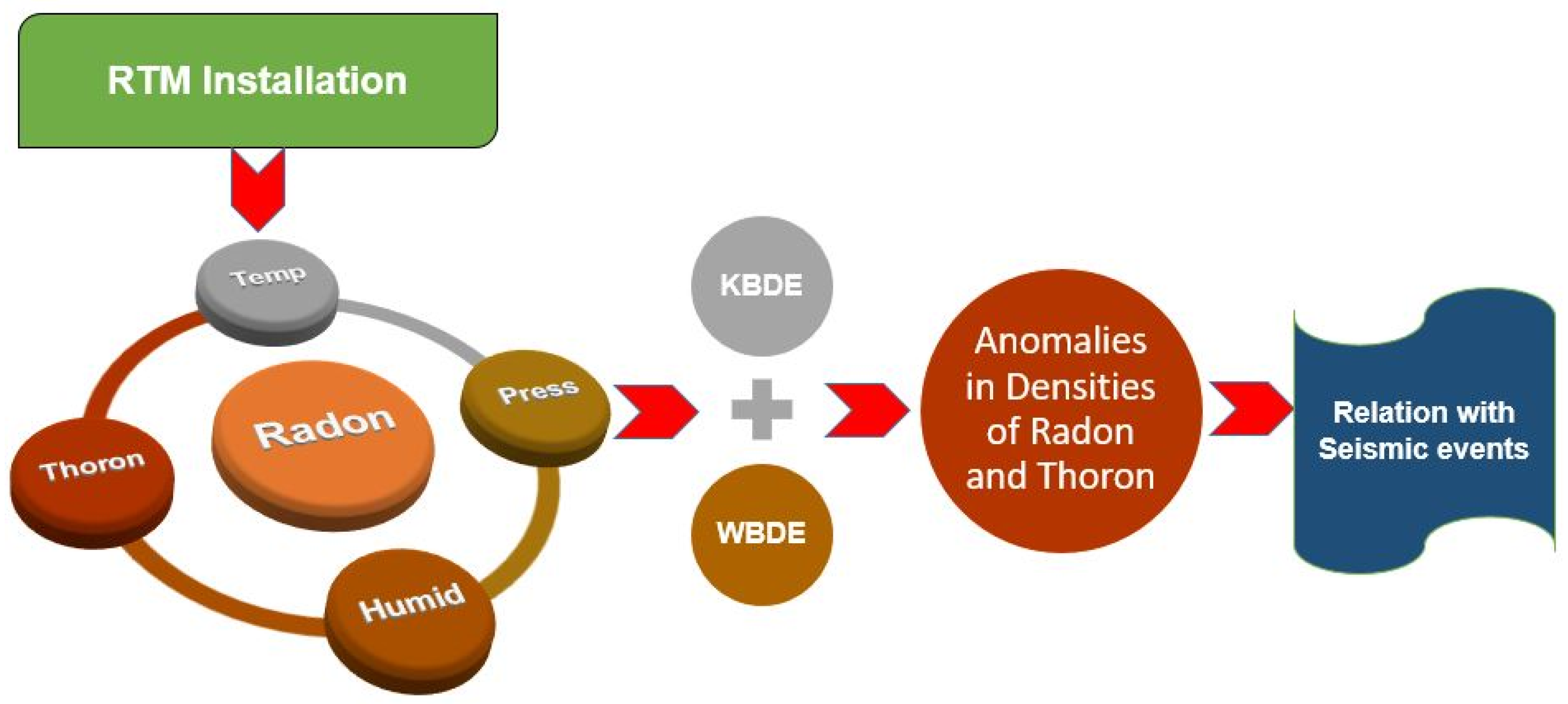

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumental Aspects

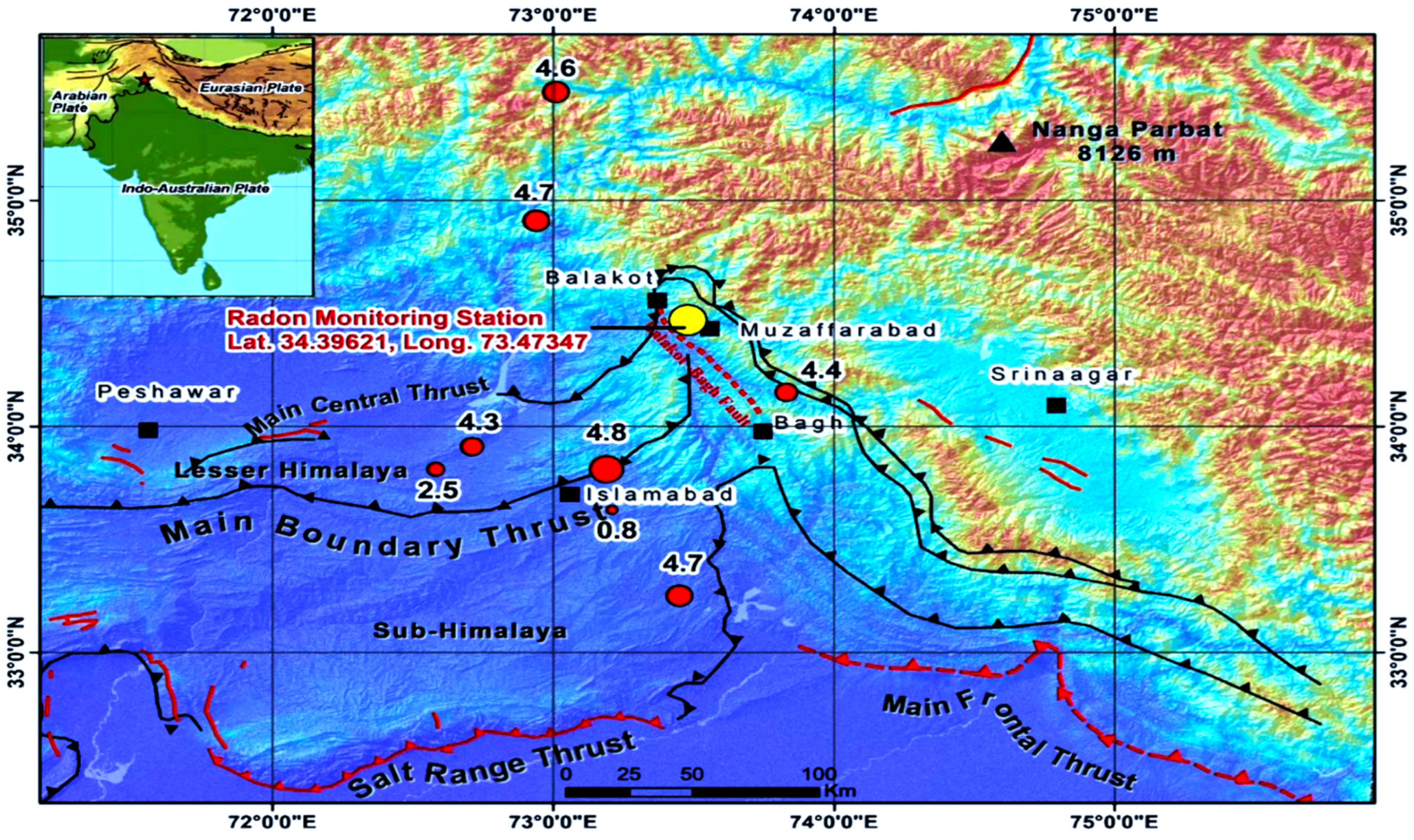

2.1.1. Geology of the Study Area

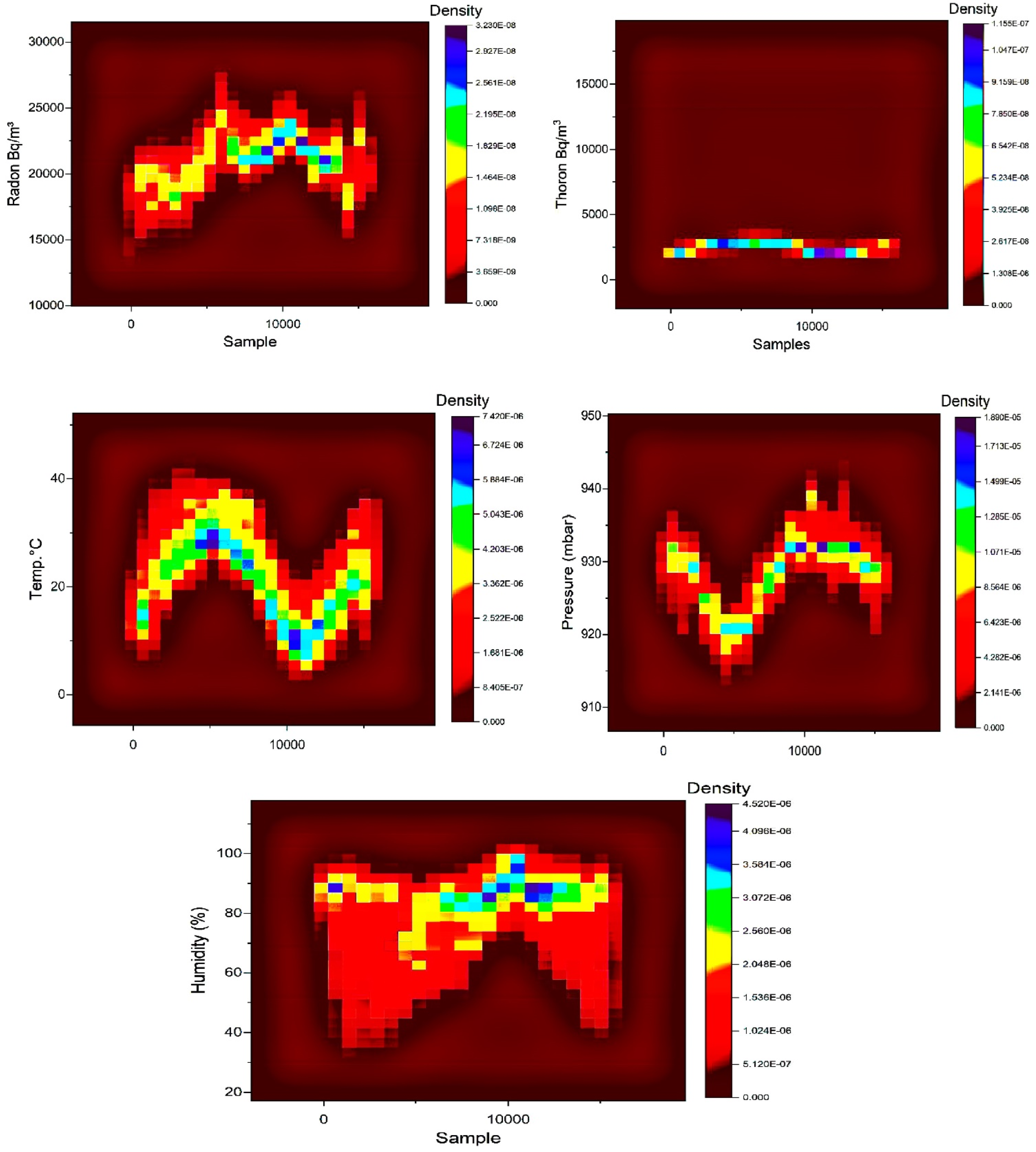

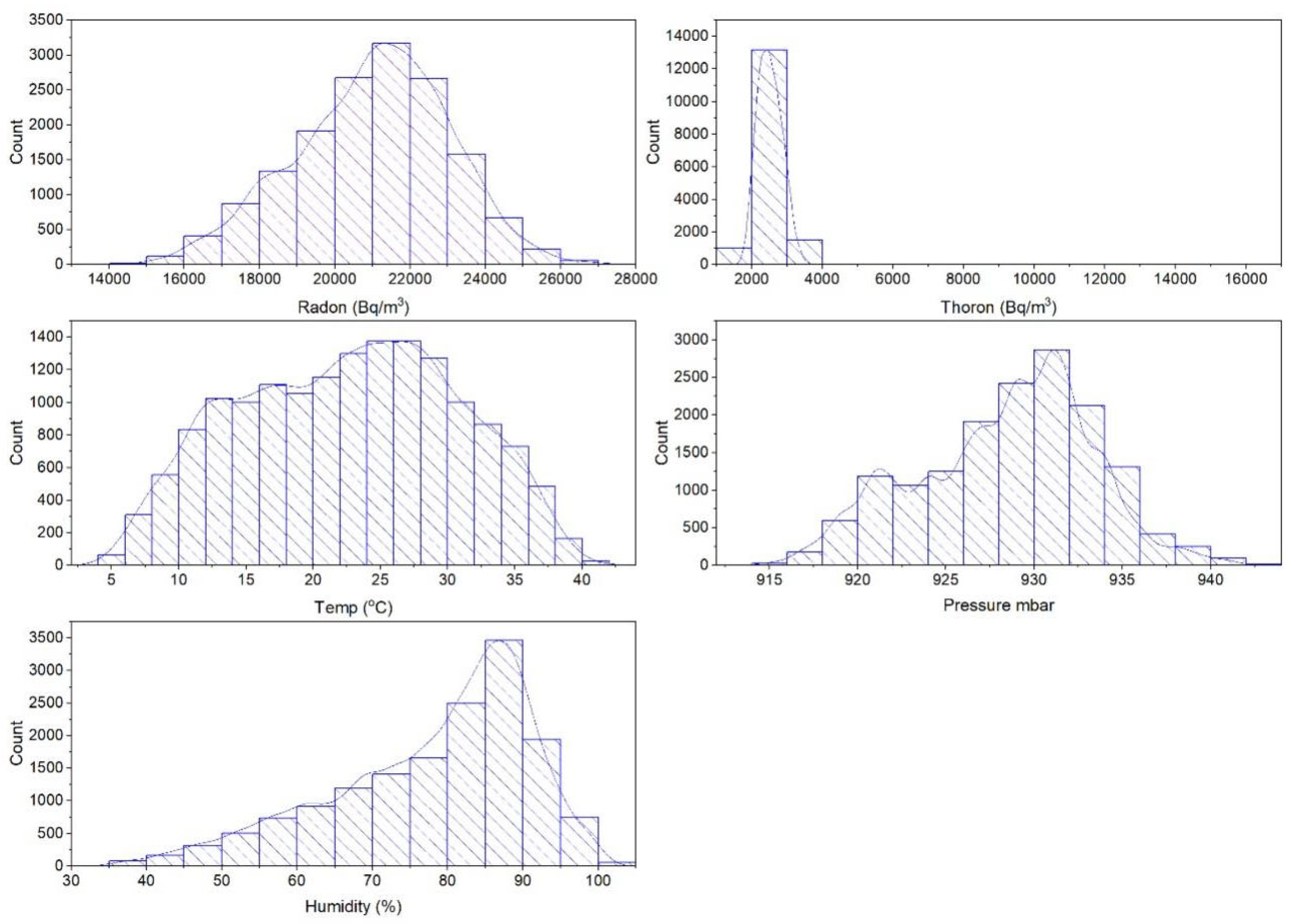

2.1.2. Data Acquisition

2.1.3. Earthquake Related Data

2.2. Theoretical Aspects

2.2.1. Kernel Density Estimation

2.2.2. Histogram-Based Density Estimation

2.2.3. Wavelet-Based Density Estimation

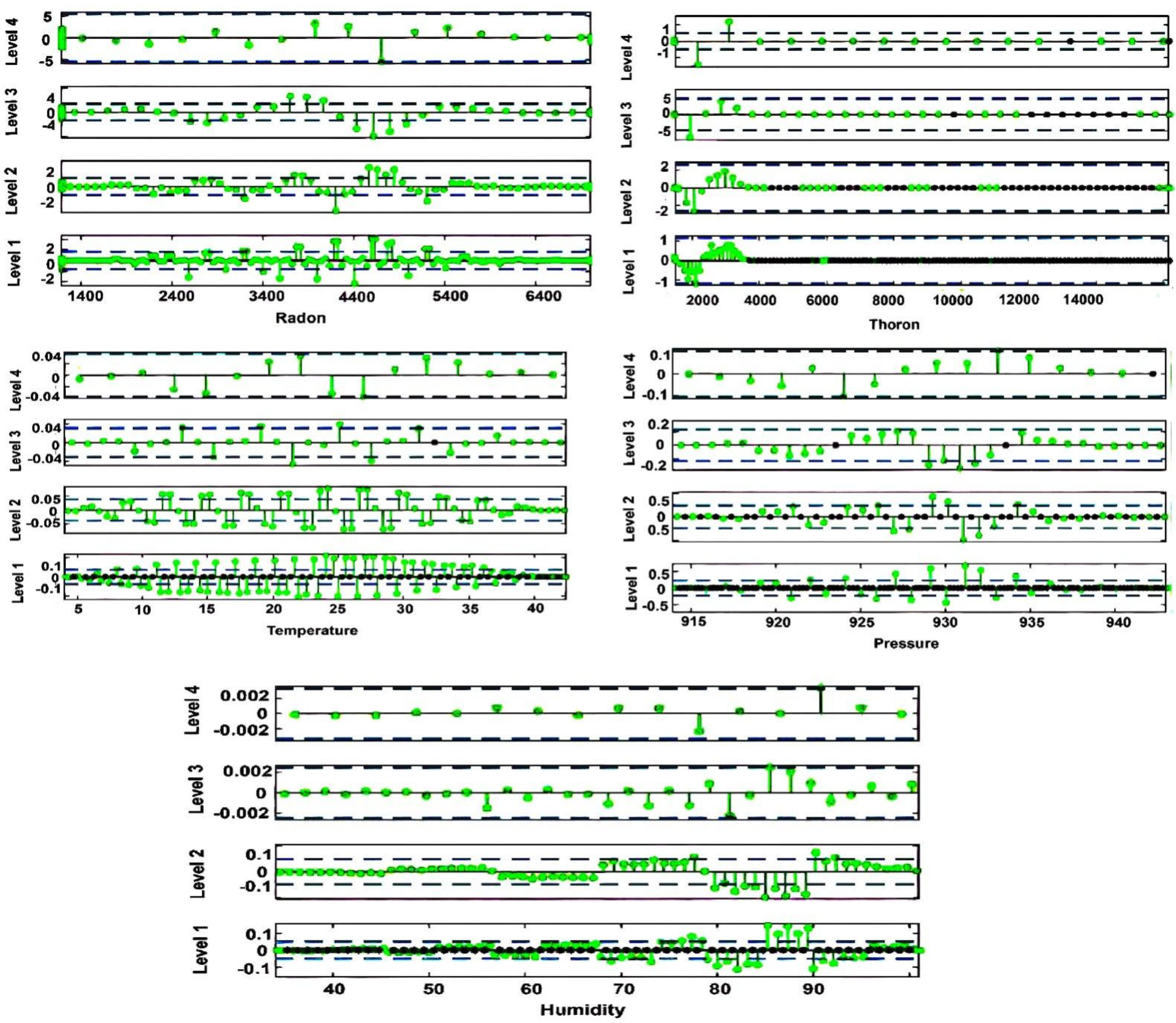

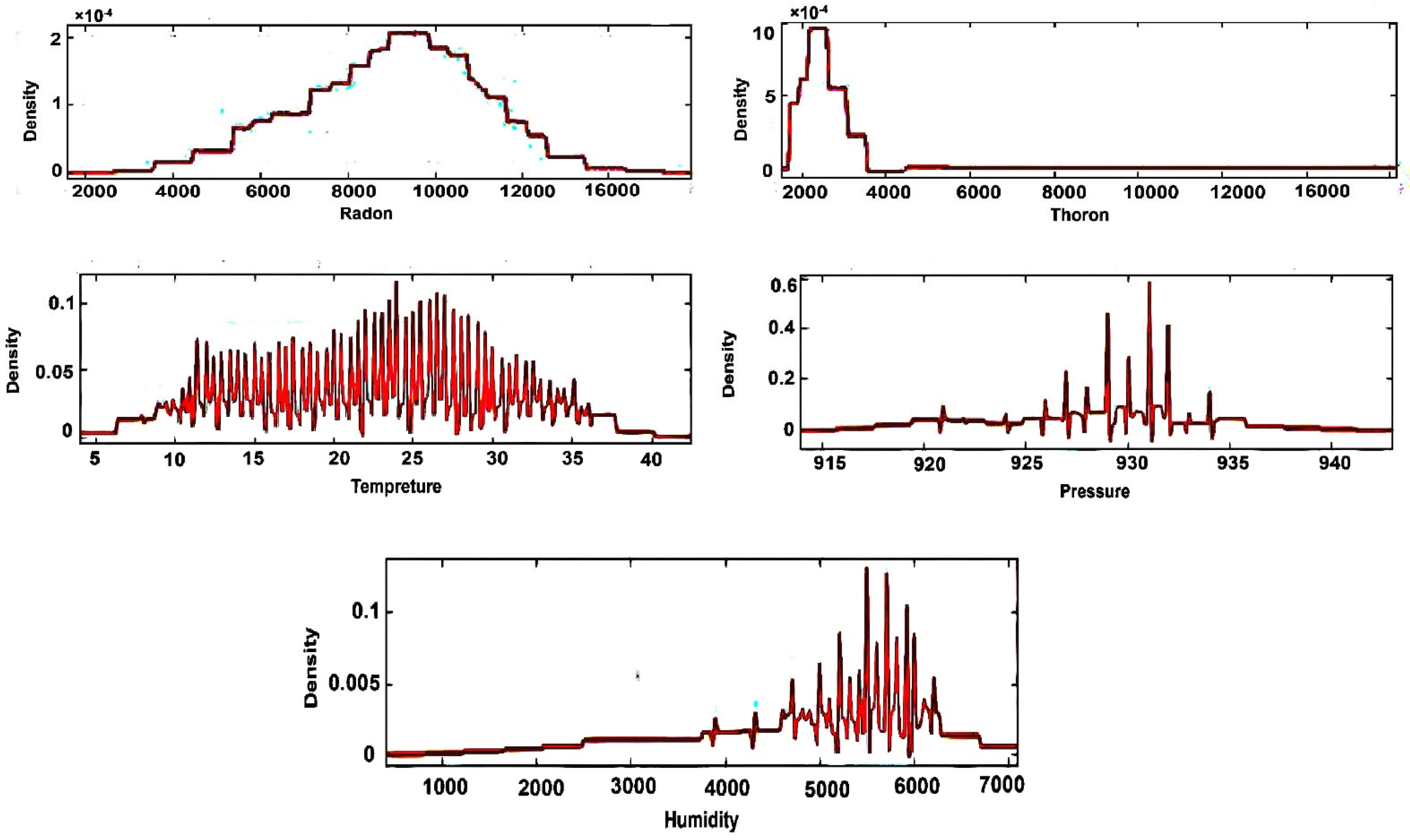

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woith, H.; Petersen, G.; Hainzl, S.; Dahm, T. Review: Can Animals Predict Earthquakes? Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2018, 108, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuyep, L.C.; Kadiri, U.A.; Monday, I.A.; Nansak, N.E.; Zakka, L.; Thomas, H.Y.; Ogugua, E.P. Geo-Chemical Techniques for Earthquake Forecasting in Nigeria. Asian J. Geogr. Res. 2021, 4, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placinta, A.O.; Borleanu, F.; Moldovan, I.A.; Coman, A. Correlation Between Seismic Waves Velocity Changes and the Occurrence of Moderate Earthquakes at the Bending of the Eastern Carpathians (Vrancea). Acoustics 2022, 4, 934–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Ge, Z. Cascading multi-segment rupture process of the 2023 Turkish earthquake doublet on a complex fault system revealed by teleseismic P wave back projection method. Earthq. Sci. 2024, 37, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Cantzos, D.; Alam, A.; Dimopoulos, S.; Petraki, E. Electromagnetic and Radon Earthquake Precursors. Geosciences 2024, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Picozza, P.; Sotgiu, A. A Critical Review of Ground Based Observations of Earthquake Precursors. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 676766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Nagahama, H.; Muto, J.; Hirano, M.; Yasuoka, Y. Detection of atmospheric radon concentration anomalies and their potential for earthquake prediction using Random Forest analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetia, T.; Baruah, S.; Dey, C.; Baruah, S.; Sharma, S. Seismic induced soil gas radon anomalies observed at multiparametric geophysical observatory, Tezpur (Eastern Himalaya), India: An appraisal of probable model for earthquake forecasting based on peak of radon anomalies. Nat. Hazards 2022, 111, 3071–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, D.; Sabatino, G.; Magazù, S.; Bella, M.D.; Tripodo, A.; Gattuso, A.; Italiano, F. Distribution of soil gas radon concentration in north-eastern Sicily (Italy): Hazard evaluation and tectonic implications. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.; Herrera, V.M.V. Earthquake Precursors: The Physics, Identification, and Application. Geosciences 2024, 14, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Radon. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/radon-and-health (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Kashkinbayev, Y.; Bakhtin, M.; Kazymbet, P.; Lesbek, A.; Kazhiyakhmetova, B.; Hoshi, M.; Altaeva, N.; Omori, Y.; Tokonami, S.; Sato, H.; et al. Influence of Meteorological Parameters on Indoor Radon Concentration Levels in the Aksu School. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Lv, W.; Huang, R.; Feng, Y.; Luo, O.; Yin, C.; Yang, Y. Impact of environmental factors on atmospheric radon variations at China Jinping Underground Laboratory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C. Featured Anomaly Detection Methods and Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Exeter, Computer Science Department, Exeter, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique, M.; Tareen, A.D.K.; Mir, A.A.; Sajjad, M.; Nadeem, A.; Asim, K.M.; Kearfott, K.J. Delegated Regressor, A Robust Approach for Automated Anomaly Detection in the Soil Radon Time Series Data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudriki Semlali, B.-E.; Molina, C.; Carvajal Librado, M.; Park, H.; Camps, A. Potential Earthquake Proxies from Remote Sensing Data; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C. A Tutorial on Kernel Density Estimation and Recent Advances. Biostat. Epidemiol. 2017, 1, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzen, E. On Estimation of a Probability Density Function and the Mode. Ann. Math. Stat. 1962, 33, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxhammar, R.; Falkman, G.; Sviestins, E. Anomaly detection in sea traffic—A comparison of the Gaussian Mixture Model and the Kernel Density Estimator. In Proceedings of the 2009 12th International Conference on Information Fusion, Seattle, WA, USA, 6–9 July 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 756–763. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanna, C.K.; Dodagoudar, G.R. Seismic hazard analysis using the adaptive Kernel density estimation technique for Chennai City. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2012, 169, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, J.; Karim, R. Adaptive kernel density-based anomaly detection for nonlinear systems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2018, 139, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordestani, M.; Alkhateeb, A.; Rezaeian, I.; Rueda, L.; Saif, M. A new clustering method using wavelet based probability density functions for identifying patterns in time-series data. In 2016 IEEE EMBS International Student Conference (ISC), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29–31 May 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Treviño, E.S.; Barria, J.A. Online wavelet-based density estimation for non-stationary streaming data. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2012, 56, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, M.; Rahman, A.-U.; Samiullah; Khan, A. Extent and evaluation of flood resilience in Muzaffarabad City, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. J. Himal. Earth Sci. 2021, 54, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, M.S.; Lawrence, R.D.; Snee, L.W. Precambrian to early Cambrian orogeny in the northwest Himalaya, Pakistan. Geolog. Mag. 1988, 125, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Wang, N.; Zhao, G.; Barkat, A. Implication of Radon Monitoring for Earthquake Surveillance Using Statistical Techniques: A Case Study of Wenchuan Earthquake. Geofluids 2020, 2020, 2429165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, H.; Nakata, T.; Tsutsumi, H.; Kondo, H.; Sugito, N.; Awata, Y.; Kausar, A.B. Surface rupture of the 2005 Kashmir, Pakistan, earthquake and its active tectonic implications. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2008, 98, 521–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS (United States Geological Survey). M 7.6—21 km NNE of Muzaffarabad, Pakistan—Pakistan earthquake 2005. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp000e12e/executive (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- SARAD GmbH. Available online: https://www.sarad.de/product-detail.php?lang=en_US&catID=&p_ID=20 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- National Seismic Monitoring Centre, Islamabad. Available online: https://seismic.pmd.gov.pk/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Dobrovolsky, I.P.; Zubkov, S.I.; Miachkin, V.I. Estimation of the size of earthquake preparation zones. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1979, 117, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, M.; Lazzari, M.; Murgante, B. Kernel Density Estimation Methods for a Geostatistical Approach in Seismic Risk Analysis: The Case Study of Potenza Hilltop Town (Southern Italy). In Lecture Notes in Computer Science Computational Science and Its Application ICCSA 2008; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Laganà, A., Taniar, D., Mun, Y., Gavrilova, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5072, pp. 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador Luna, D.; Alonso-Chaves, F.M.; Fernández, C. Kernel Density Estimation for the Interpretation of Seismic Big Data in Tectonics Using QGIS: The Türkiye–Syria Earthquakes (2023). Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine learning—A probabilistic perspective. In Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning Series; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frehner, R.; Wu, K.; Sim, A.; Kim, J.; Stockinger, J. Detecting Anomalies in Time Series Using Kernel Density Approaches. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 33420–33439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Gao, J.; Li, B.; Wu, O.; Du, J.; Maybank, S. Anomaly Detection Using Local Kernel Density Estimation and Context-Based Regression. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 32, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torshizian, H.; Afzal, P.; Rahbar, K.; Yasrebi, A.B.; Wetherelt, A.; Fyzollahhi, N. Application of modified wavelet and fractal modeling for detection of geochemical anomaly. Geochemistry 2021, 81, 125800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ma, J.; Ye, Y. Regularizing autoencoders with wavelet transform for sequence anomaly detection. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 134, 109084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Rashid, M.M.; Johnson, F.; Sharma, A. A wavelet-based tool to modulate variance in predictors: An application to predicting drought anomalies. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 135, 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Dong, Q.; Hao, M.; Wang, C.; Cao, J. Magnetic anomaly detection based on fast convergence wavelet artificial neural network in the aeromagnetic field. Measurement 2021, 176, 109097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halidou, A.; Mohamadou, Y.; Ari, A.A.A.; Zacko, E.J.G. Review of wavelet denoising algorithms. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 41539–41569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Osama, M.; Rafique, M.; Tareen, A.D.K.; Lone, K.J.; Qureshi, S.A.; Kearfott, K.J.; Aftab, A.; Nikolopoulos, D. Time-frequency analysis of radon and thoron data using continuous wavelet transform. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfaoui, S.; Ben Mabrouk, A.; Cattani, C. Wavelet Analysis: Basic Concepts and Applications, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–254. ISBN 9781003096924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, K.A.; Wegman, E. Nonparametric density estimation of streaming data using orthogonal series. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 3980–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Sharma, A.; Johnson, F. Assessing the sensitivity of hydro-climatological change detection methods to model uncertainty and bias. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 134, 103430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.V.; Barnard, V.O. Optimal Location Estimation and Anomaly Quantification for a Mobile Information Carrier: Prior Feeds for Deep Learning. 8th International Conference on Civil, Structural and Transportation Engineering, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 4–6 June 2023; Avestia Publishing: Orleans, ON, Canada, 2023; p. 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, T.K.; Jain, M.K.; Yadav, B.K.; Agarwal, A. Multiscale investigation of precipitation extremes over Ethiopia and teleconnections to large-scale climate anomalies. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 1503–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves-Kirkby, C.J.; Denman, A.R.; Crockett, R.G.M.; Phillips, P.S.; Gillmore, G.K. Identification of tidal and climatic influences within domestic radon time-series from Northamptonshire, UK. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 367, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftaxias, K. Footprints of nonextensive Tsallis statistics, selfaffinity and universality in the preparation of the L’Aquila earthquake hidden in a pre-seismic EM emission. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2010, 389, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EQ | Date | Magnitude | Latitude N | Longitude E | Depth (km) | (km) | (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ1 | 21 March 2017 | 4.3 | 33.91 N | 72.71 E | 25 | 86.00 | 70.60 |

| EQ2 | 23 March 2017 | 2.5 | 33.81 N | 72.58 E | 156 | 103.0 | 11.89 |

| EQ3 | 27 August 2017 | 4.8 | 33.81 N | 73.19 E | 10 | 66.34 | 115.9 |

| EQ4 | 23 September 2017 | 4.6 | 35.48 N | 73.01 E | 61 | 135.0 | 95.06 |

| EQ5 | 9 December 2017 | 4.7 | 33.25 N | 76.45 E | 101 | 300.0 | 104.9 |

| EQ6 | 3 February 2018 | 0.8 | 33.63 N | 73.21 E | 157 | 142.9 | 2.208 |

| EQ7 | 28 February 2018 | 4.4 | 34.15 N | 73.83 E | 134 | 41.78 | 77.98 |

| EQ8 | 14 March 2018 | 4.9 | 33.93 N | 77.12 E | 10 | 343.0 | 127.9 |

| EQ9 | 15 March 2018 | 4.7 | 33.1 N | 76.14 E | 45 | 284.5 | 105.0 |

| EQ | Radon Time Series | Thoron Time Series | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDE | WBDE | KDE | WBDE | |

| EQ1 | 1.46 × 10−8 | 0.11 × 10−4 | 1.30 × 10−8 | 4.63 × 10−4 |

| EQ2 | 1.09 × 10−8 | 0.26 × 10−4 | 2.62 × 10−8 | 6.71 × 10−4 |

| EQ3 | 1.83 × 10−8 | 0.95 × 10−4 | 7.85 × 10−8 | 0.12 × 10−4 |

| EQ4 | 1.46 × 10−8 | 1.23 × 10−4 | 9.16 × 10−8 | 0.12 × 10−4 |

| EQ5 | 2.19 × 10−8 | 1.12 × 10−4 | 9.16 × 10−8 | 0.12 × 10−4 |

| EQ6 | 7.32 × 10−9 | 1.56 × 10−4 | 1.55 × 10−7 | 0.12 × 104 |

| EQ7 | 2.93 × 10−8 | 0.42 × 104 | 1.05 × 10−7 | 0.12 × 104 |

| EQ8 | 3.65 × 10−9 | 0.31 × 104 | 3.93 × 10−8 | 0.12 × 104 |

| EQ9 | 2.56 × 10−8 | 0.11 × 104 | 2.62 × 10−8 | 0.12 × 104 |

| Cut-off limit | 3.14 × 10−8 | 4.14 × 103 | 1.63 × 10−7 | 1.80 × 102 |

| Type of Variables | Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Radon vs. Air Temperature | −0.141 |

| Radon vs. Atmospheric Pressure | 0.121 |

| Radon vs. Percentage Humidity | 0.432 |

| Thoron vs. Temperature | 0.579 |

| Thoron vs. Pressure | −0.510 |

| Thoron vs. Percentage Humidity | −0.211 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rafique, M.; Rasheed, A.; Osama, M.; Mir, A.A.; Nikolopoulos, D.; Kiskira, K.; Alam, A.; Prezerakos, G.; Javed, A.; Yannakopoulos, P.; et al. Detecting Anomalies in Radon and Thoron Time Series Data Using Kernel and Wavelet Density Estimation Methods. Geosciences 2026, 16, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16020064

Rafique M, Rasheed A, Osama M, Mir AA, Nikolopoulos D, Kiskira K, Alam A, Prezerakos G, Javed A, Yannakopoulos P, et al. Detecting Anomalies in Radon and Thoron Time Series Data Using Kernel and Wavelet Density Estimation Methods. Geosciences. 2026; 16(2):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16020064

Chicago/Turabian StyleRafique, Muhammad, Awais Rasheed, Muhammad Osama, Adil Aslam Mir, Dimitrios Nikolopoulos, Kyriaki Kiskira, Aftab Alam, Georgios Prezerakos, Aqib Javed, Panayiotis Yannakopoulos, and et al. 2026. "Detecting Anomalies in Radon and Thoron Time Series Data Using Kernel and Wavelet Density Estimation Methods" Geosciences 16, no. 2: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16020064

APA StyleRafique, M., Rasheed, A., Osama, M., Mir, A. A., Nikolopoulos, D., Kiskira, K., Alam, A., Prezerakos, G., Javed, A., Yannakopoulos, P., Drosos, C., Priniotakis, G., Gerolimos, N., Papoutsidakis, M., Kearfott, K. J., & Rahman, S. U. (2026). Detecting Anomalies in Radon and Thoron Time Series Data Using Kernel and Wavelet Density Estimation Methods. Geosciences, 16(2), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16020064