The Geological Heritage of Príncipe Island (West Africa)

Abstract

1. Introduction

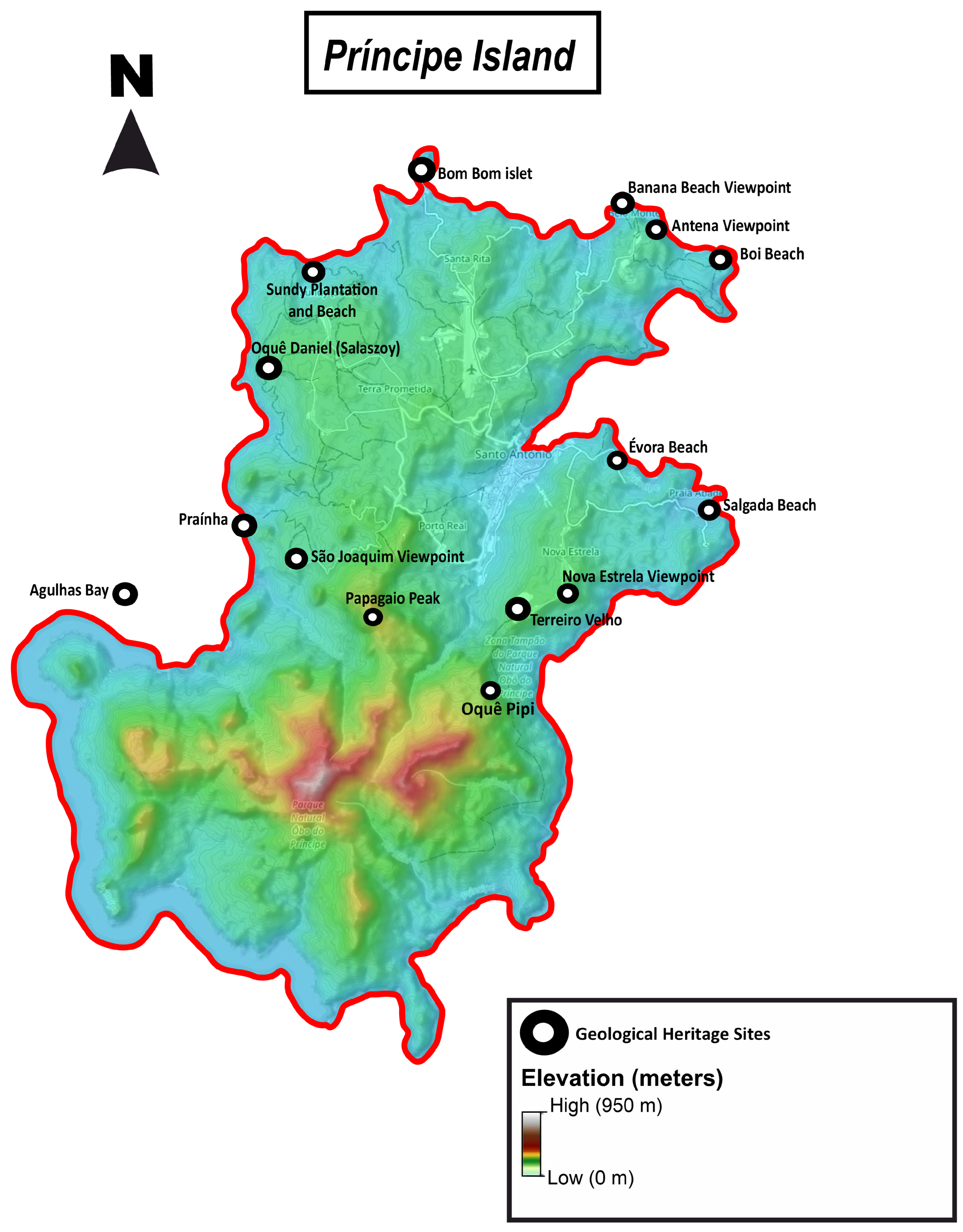

2. Study Area

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Geological Heritage Sites Inventorying and Assessment

4.1.1. Bom Islet

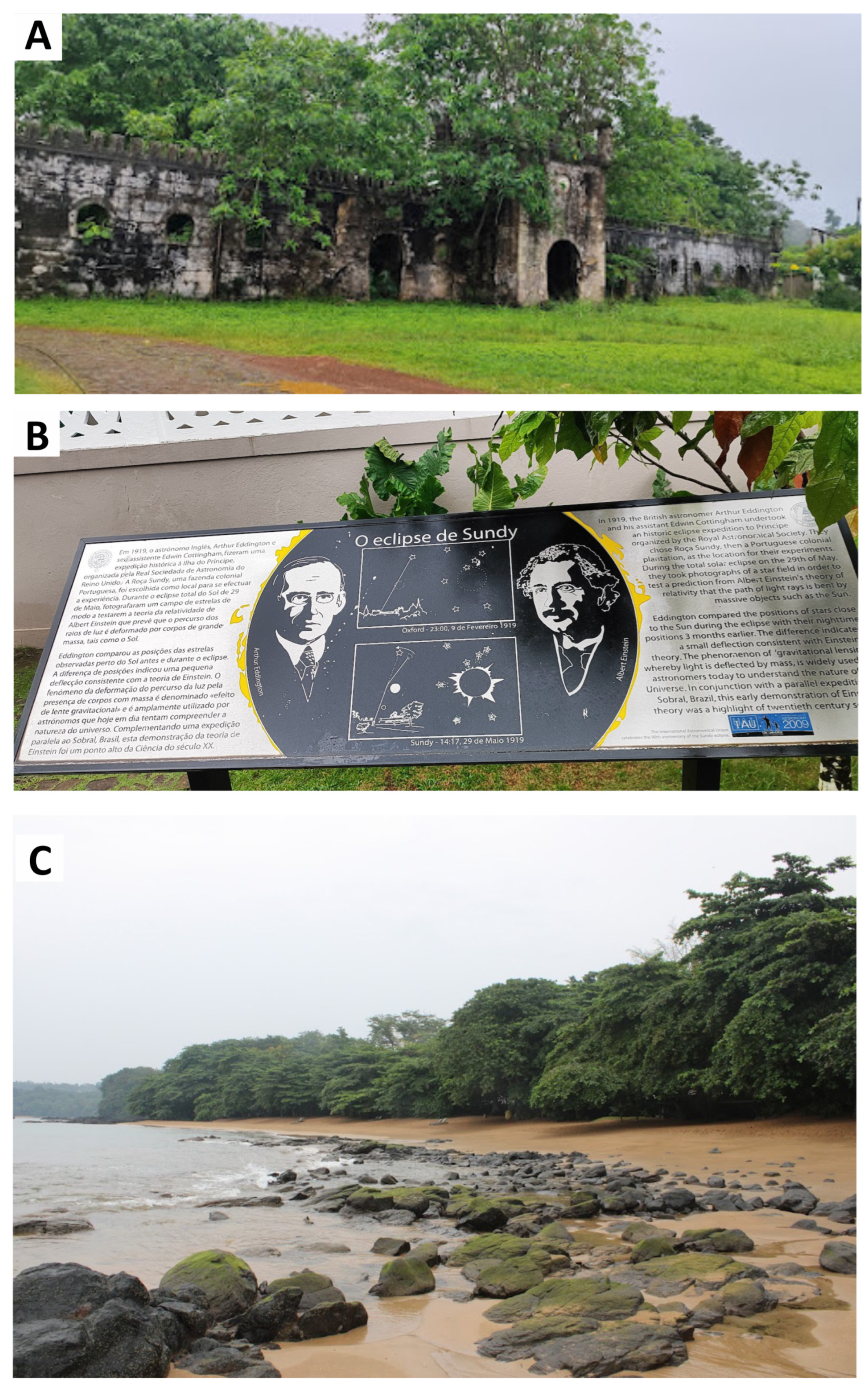

4.1.2. Sundy Plantation and Sundy Beach

4.1.3. Agulhas Bay

4.1.4. Nova Estrela Viewpoint

4.1.5. Antena Viewpoint

4.1.6. Banana Beach Viewpoint

4.1.7. Roça Terreiro Velho

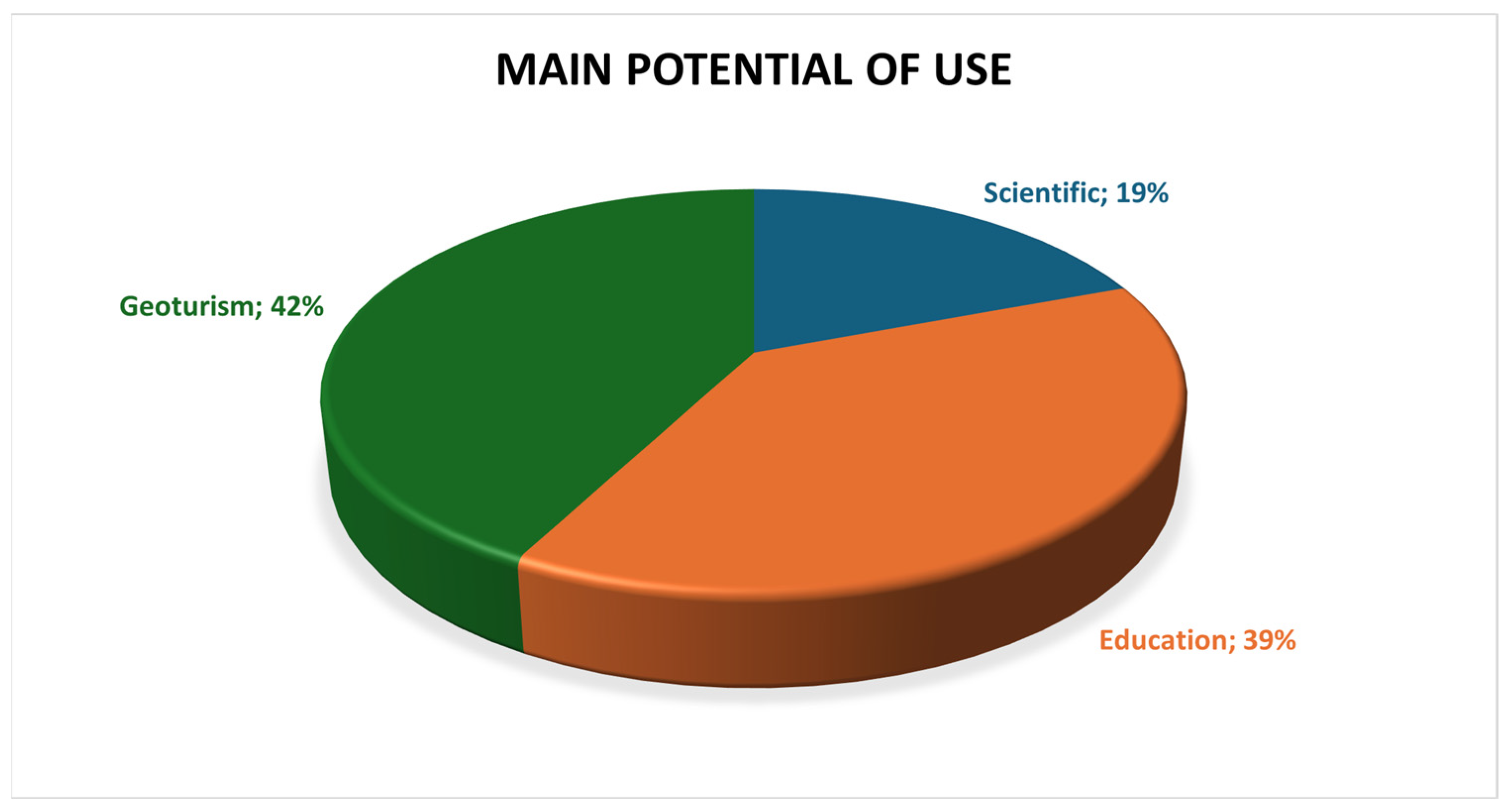

4.2. Types and Potential Use

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity and Geoconservation: What, why, and How? In The George Wright Forum; George Wright Society Conference: Hancock, MI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, P.; Sutcliffe, P.; Hjort, J.; Faith, D.P.; Pressey, R. A review of selection-based tests of abiotic surrogates for species representation. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J. Património Geológico e Geoconservação: A Conservação da Natureza na sua Vertente Geológica; Editora Palimage: Viseu, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tukiainen, H.; Toivanen, M.; Maliniemi, T. Geodiversity and Biodiversity. In Geological Society; Special Publications: London, UK, 2023; Volume 530, pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, M.; Reis, R.; Brilha, J.; Mota, T. Geoconservation as an Emerging Geoscience. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, K.; Henriques, M.H. Geoconservation in Africa: State of the art and future challenges. Gondwana Res. 2022, 110, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K. Origin of the Cameroon Line of Volcano-Capped Swells. J. Geol. 2001, 109, 349–362. [Google Scholar]

- Toteu, S.F.; Malcolm Anderson, J.; de Wit, M. “Africa Alive Corridors”: Forging a new future for the people of Africa by the people of Africa. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2010, 58, 692–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linol, B.; Doucouré, M.; Anderson, J.; Toteu, F.; Miller, W.; Vale, P.; Hoffman, P.; Kerley, G.I.H.; Auerbach, R.; Thiart, C.; et al. Africa Alive Corridors: Transdisciplinary Research based on African Footprints. Geoheritage 2024, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.J. Biodiversity in the Gulf of Guinea: An overview. Biodivers. Conserv. 1994, 3, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceríaco, L.M.P.; de Lima, R.F.; Melo, M.; Bell, R.C. Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: Science and Conservation; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, K.; Henriques, M.H. Geoheritage of the São Tomé Island (West Africa). Geoheritage 2025, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, K.; Henriques, M.H. Geoheritage of the Príncipe UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve (West Africa): Selected Geosites. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena dos Reis, R.; Henriques, M.H. Approaching an Integrated Qualification and Evaluation System for Geological Heritage. Geoheritage 2009, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.C.; Smith, M. (Eds.) Geosciences and the Sustainable Development Goals; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, J. Geology and the Sustainable Development Goals. Episodes 2016, 40, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaudo, A.; Lozar, F.; Lasagna, M.; Tonon, M.D.; Egidio, E. For a Sustainable Future: A Survey about the 2030 Agenda among the Italian Geosciences Community. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, K. Sustainable Development Goals and Geosciences: A Review. Earth Sci. Syst. Soc. 2024, 4, 10124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownfield, M.E.; Charpentier, R.R. Geology and Total Petroleum Systems of the Gulf of Guinea Province of West Africa; US Geological Survey Bulletin 2207-C; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2006; 32p. [Google Scholar]

- Heldberg. A Geological Analysis of the Cameroon Trend. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/d36bfb1f4c9f5da73d0470747ac7fbf0/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Moreau, C.; Regnoult, J.M.; Déruelle, B.; Robineau, B. A new tectonic model for the Cameroon Line, Central Africa. Tectonophysics 1987, 139, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déruelle, B.; Moreau, C.; Nkoumbou, C.; Kambou, R.; Lissom, J.; Emmanuel, N.; Ghogomu Tih, R.; Nono, A. The Cameroon Line: A Review. In Magmatism in Extensional Structural Settings; The Phanerozoic African Plate; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 274–327. [Google Scholar]

- Déruelle, B.; Ngounouno, I.; Demaiffe, D. The ‘Cameroon Hot Line’ (CHL): A unique example of active alkaline intraplate structure in both oceanic and continental lithospheres. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2007, 339, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamgouot, F.N.; Déruelle, B.; Mbowou, I.B.G.; Ngounouno, I. Petrology of the Volcanic Rocks from Bioko Island (“Cameroon Hot Line”). Int. J. Geosci. 2015, 6, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, J.B.; Rosendahl, B.R.; Harrison, C.G.A.; Ding, Z.D. Deep-imaging seismic and gravity results from the offshore Cameroon Volcanic Line, and speculation of African hotlines. Tectonophysics 1998, 284, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, T.; Trauth, M.H. São Tomé et Príncipe. In Geological Atlas of Africa. Geological Atlas of Africa: With Notes on Stratigraphy, Tectonics, Economic Geology, Geohazards and Geosites of Each Country; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 192–193. [Google Scholar]

- Fitton, J.G.; Hughes, D.J. Petrochemistry of the volcanic rocks of the Island of Principe, Gulf of Guinea. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1977, 64, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, H.M.; Fitter, J.G. A K-Ar and Sr-isotopic study of the volcanic rocks of the island of Príncipe, West Africa—Evidence for mantle heterogeneity beneath the Gulf of Guinea. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1979, 71, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiva, J.M.C. Contribuição para o estudo geológico e geomorfológico de São Tomé e ilhéu das Rolas das Cabras. Int. West Afr. Conf. 1956, 147–153. Available online: https://search.library.northwestern.edu/discovery/fulldisplay?vid=01NWU_INST:NULVNEW&docid=alma9977757364202441&context=L (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Pool-Stanvliet, R.; Clüsener-Godt, M. AfriMAB: Biosphere Reserves in Sub-Saharan Africa; Showcasing Sustainable Development. Man Biosph. 2013, 284–331. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000226919 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Tavares, A.O.; Henriques, M.H.; Domingos, A.; Bala, A. Community Involvement in Geoconservation: A Conceptual Approach Based on the Geoheritage of South Angola. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-González, E.; Vegas, J.; Galindo, I.; Romero, C.; Sánchez, N. Volcanic Islands as Reservoirs of Geoheritage-age: Current and Potential Initiatives of Geoconservation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1420. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Caicedo-Potosí, J.; Berrezueta, E. Geoheritage and Geosites: A Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Review. Geosciences 2022, 12, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, G.H. Nota sobre a microfauna do Miocénico marinho da ilha do Príncipe. In Memórias e Notícias; Publicações do Museu e Laboratório Mineralógico e Geológico da Universidade de Coimbra e do Centro de Estudos Geológicos: Coimbra, Portugal, 1958; Volume 45, pp. 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, M.H.; Pena dos Reis, R. Storytelling the Geoheritage of Viana do Castelo (NW Portugal). Geoheritage 2021, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, R.A. Eclipse 1919—Home. Available online: https://eclipse1919.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Corallo, C. Cacao & Coffe. Available online: https://claudiocorallo.com/index.php?lang=pt&Itemid=1038 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Habibi, T.; Ponedelnik, A.A.; Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A. Urban geoheritage complexity: Evidence of a unique natural resource from Shiraz city in Iran. Resour. Policy 2018, 59, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matshusa, K.; Leonard, L.; Thomas, P. Challenges of Geotourism in South Africa: A Case Study of the Kruger National Park. Resources 2021, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.S.; Nyaupane, G.P. Africans and protected areas: North–South perspectives. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J. Inventory and Quantitative Assessment of Geosites and Geodiversity Sites: A Review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Johnson, C.P. Potential Geotourism and the Prospect of Raising Awareness About Geoheritage and Environment on Mauritius. Geoheritage 2013, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cortés, Á.; Vegas, J.; Carcavilla, L.; Díaz-Martínez, E. Conceptual Base and Methodology of the Spanish Inventory of Sites of Geological Interest (IELIG); IGME: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Geological Heritage Site/Coordinates | Geoheritage Types | Main Geological Features | Geoheritage Contents | Relevance Grade |

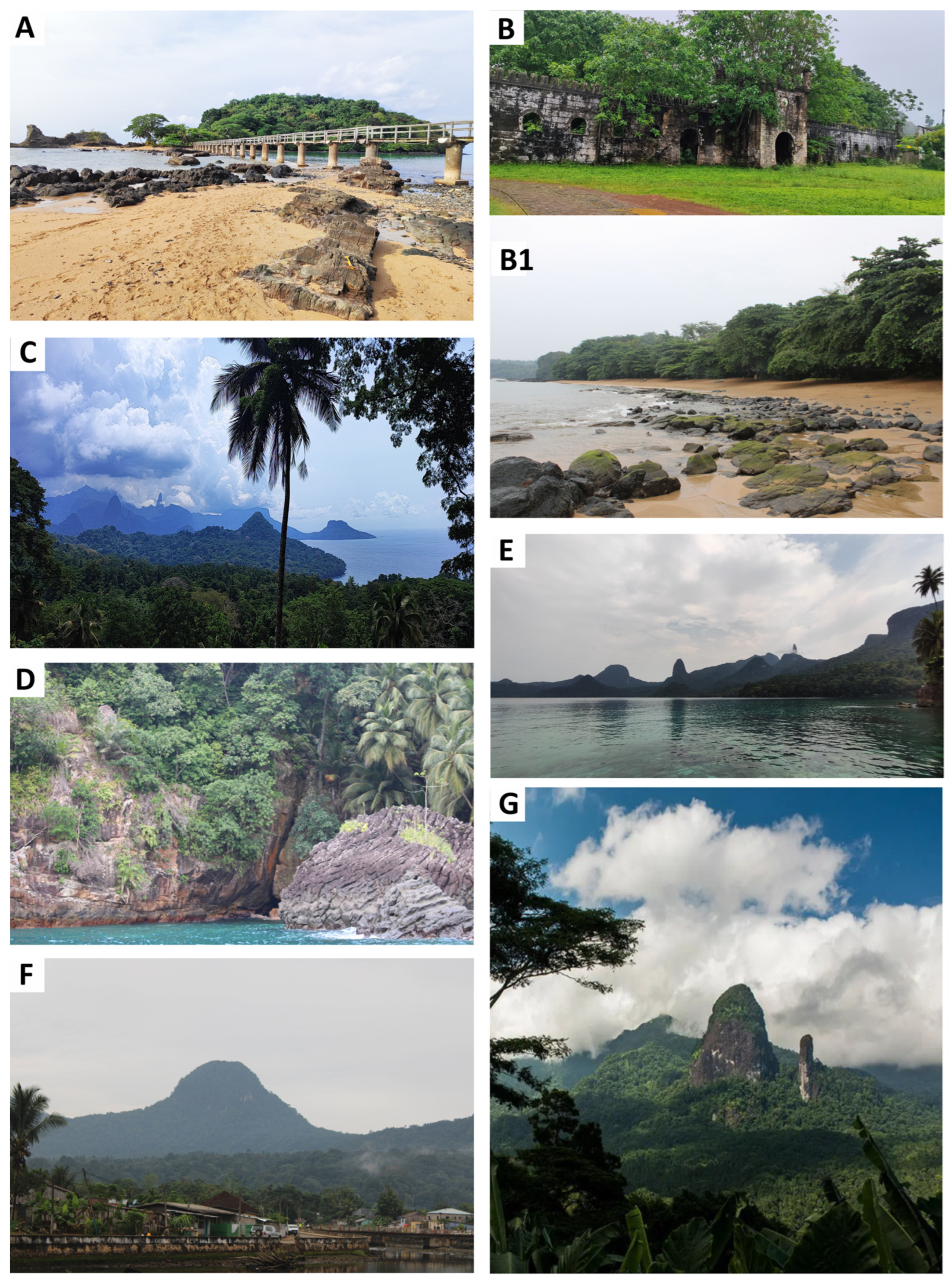

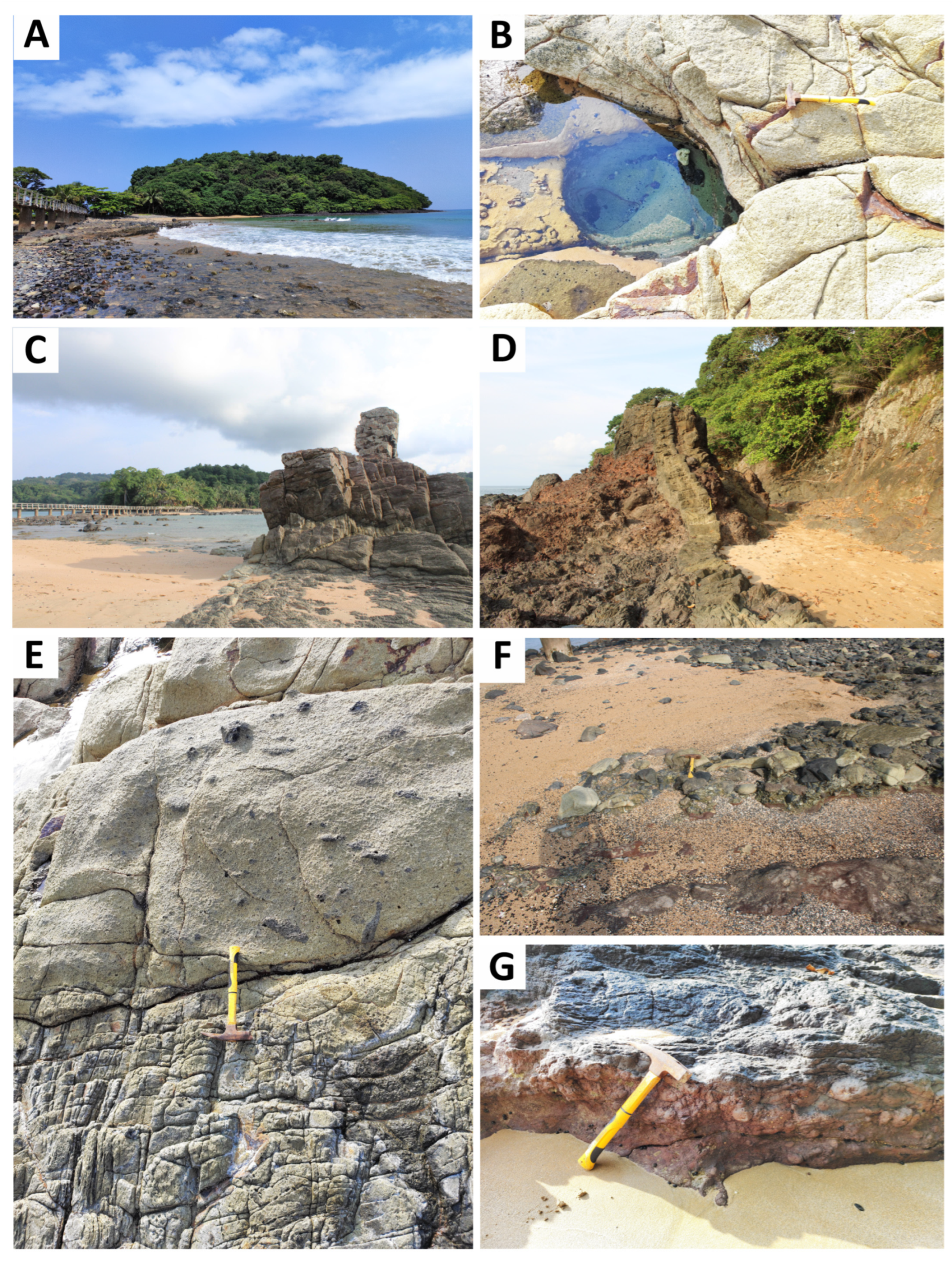

| Bom Bom Islet 1°42′3″ N, 7°24′13″ E | Volcanic Geomorphological Sedimentological Stratigraphical Tectonic | The geosite represents the interaction of volcanic and tectonic processes with maritime erosion, resulting in the formation of palagonitic breccias. These breccias occur in stratigraphic contact with the oldest series of lavas of subaerial eruptions occurred in the island (24 My), which is cut by strong parallel trachyte dykes, with a thickness of about 5 m in the N 18° E direction ([14] and references therein). | Indicial Symbolic Documental Scenic | National |

| Sundy Plantation and Sundy Beach 1°40′11″11″ N, 7°23′01″ E | Volcanic Sedimentological Geohistorical | The geosite corresponds to an historic farm stead situated within one of the most significant plantations of the island which were important to observe a solar eclipse that experimentally tested and verified Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. The coastal strip of the property is composed of a white sandy beach, with outcrops of andesite of the older series that are mixed with phonolitic rocks forming a lava tongue that extends northwards to the basaltic plateau composed of lavas of the younger series; oil seeps flowing through fractures of highly altered phonolitic rocks, accompanied by gas emissions, were recognized in the vicinity (Roça Sundy) and at Duas Águas creek ([14] and references therein). | Indicial Documental Symbolic | National |

| Praínha 1°38′01.8″ N, 7°21′52″ E | Volcanic Geomorphological Stratigraphical Tectonic | This geosite exhibits the fault plane which corresponds to the structural contact between the northern zone of the island, characterized by a relatively flat topography, and its southern zone, made up of several trachyphonolitic peaks. Seaside phonolite blocks show well defined columnar disjunction. | Iconographic Scenic | Regional |

| Agulhas Bay 1°36′20″ N, 7°20′32″ E | Volcanic Geomorphological Sedimentological Stratigraphical | In this bay, only accessible by boat, we can see numerous phonolitic and phonolitic trachyte peaks enveloped in dense rainforest, belonging to the intermediate phase of volcanic activity, which characterize the southern portion of the island ([14] and references therein). | Documental Iconographic Scenic | National |

| Papagaio Peak 1°36′43″ N, 7°23′31″ E | Volcanic Geomorphological | Papagaio Peak, a prominent 680 m high landmark, serves as the backdrop to the city of São António, which is widely regarded as the smallest city in the world. This phonolitic peak represents the intermediate series (6.9 My) and is in the Natural Park of Príncipe, created by Law 7/2006 ([14] and references therein). | Indicial Scenic | National |

| Oquê Pipi Waterfall 1°35′52″ N, 7°24′50″ E | Volcanic Geomorphological Hydrological | The spectacular waterfall, situated along a structural fault front of approximately 30 m high, enables the recognition of the most recent series of volcanism on the island ([14] and references therein). | Documental Scenic | Regional |

| Salgada Beach 1°37′56.5” N, 7°27′10.0” E | Volcanic Sedimentological Stratigraphical | The geosite shows the contact between the palagonitic breccia and the ancient series, well visible along the beachfront, where they have formed small natural pools. | Iconographic | National |

| Évora Beach 1°38′38.1” N, 7°26′21.5” E | Volcanic Stratigraphical Sedimentological | The geosite corresponds to a set of basaltic outcrops cut by a dyke aligned with the orientation of the Cameroon Volcanic Line. | Indicial | Regional |

| Boi Beach 1°40′49.0” N, 7°27′39.0” E | Volcanic Stratigraphical Sedimentological | The outcrop along the beachfront shows the contact between the palagonitic breccia and the ancient series. | Scenic Symbolic | Regional |

| Roça Terreiro Velho 1°36′37′′ N, 7°25′13′′ E | Volcanic Geomorphological | The geosite is historically significant as the site of the introduction of the first cocoa tree to the African continent in 1819, thereby establishing a tradition of cocoa cultivation that is currently represented by the prestigious Claudio Corallo cocoa. The site is also home to basaltic geological formations, offering panoramic views of Príncipe Island, including the iconic Boné do Jóquei rock formation, which highlights the symbolic and geological value of the region. | Symbolic Documental Scenic | National |

| Viewpoint | ||||

| Viewpoint Site/Coordinates | Geoheritage Types | Main Geological Features | Geoheritage Contents | Relevance Grade |

| Oquê Daniel (Salaszoy) Viewpoint 1°39′46.5” N, 7°22′44.7” E | Volcanic Geomorphological | This geosite offers visitors the opportunity to observe and appreciate the southern portion of the island of Príncipe characterized by a mountain range comprising several phonolite peaks and tephrites which host the island’s primary rainforest. | Scenic | Regional |

| São Joaquim Viewpoint 1°37′13” N, 7°22′36” E | Volcanic Geomorphological | This viewpoint provides a privileged perspective of the João Dias (Father and Son) Peaks, constituting one of the most iconic images of Príncipe Island. The various phonolitic towers visible from this site define the topography of the southern region of the island. | Scenic | Regional |

| Nova Estrela Viewpoint 1° 36′51.2” N, 7°25′37.8” E | Volcanic Geomorphological | The viewpoint corresponds to a postcard of the Príncipe Island, showcasing the “Jockey’s Cap” islet, made up of basalts of the modern series ([14] and references therein). | Symbolic Documental Scenic | National |

| Antena Viewpoint 1°41′05.7” N 7°26′51.0” E | Volcanic Geomorphological | The viewpoint offers a panoramic perspective of both Macaco Beach and Boi Beach, showcasing prominent outcrops that offer a discerning view of the superimposition of laterites upon more recent series. | Symbolic Documental Scenic | Regional |

| Banana Beach Viewpoint 1°41′16.1” N 7°26′36.3” E | Volcanic Geomorphological Sedimentological | The most prominent viewpoint in the country, which offers a view of the renowned Banana Beach, is characterized by a white sand beach with substantial blocks of basaltic nature. | Symbolic Documental Scenic | National |

| Geosite | Geoheritage Contents | Qualitative Assessment | Geoconservation Priority | Risk of Degradation |

| Bom Bom Islet | Indicial Symbolic Documental Scenic | Rank I Rank II Rank III | 1st | Natural vulnerability Anthropogenic Vulnerability Public use |

| Sundy Plantation and Sundy Beach | Indicial Documental Symbolic | Rank I Rank II Rank III | 1st | Natural vulnerability Public use |

| Roça Terreiro Velho | Symbolic Documental Scenic | Rank I Rank II Rank III | 1st | Anthropogenic Vulnerability Public use |

| Praínha | Iconographic Scenic | Rank I Rank III | 2nd | Natural vulnerability |

| Agulhas Bay | Documental Iconographic Scenic | Rank II Rank III | 1st | Natural vulnerability |

| Papagaio Peak | Indicial Scenic | Rank I Rank III | 2nd | Natural vulnerability |

| Oquê Pipi Waterfall | Documental Scenic | Rank II Rank III | 2nd | Natural vulnerability |

| Salgada Beach | Iconographic | Rank II | 1st | Natural vulnerability Anthropogenic Vulnerability Public use |

| Évora Beach | Indicial | Rank I | 3rd | Natural vulnerability Anthropogenic Vulnerability Public use |

| Boi Beach | Symbolic Scenic | Rank II Rank III | 1st | Natural vulnerability Anthropogenic Vulnerability Public use |

| Viewpoint | ||||

| Viewpoint | Geoheritage Contents | Qualitative Assessment | Geoconservation Priority | Risk of Degradation |

| Antena Viewpoint | Symbolic Documental Scenic | Rank I Rank II Rank III | 1st | Natural vulnerability |

| Nova Estrela Viewpoint | Symbolic Documental Scenic | Rank I Rank II Rank III | 1st | Natural vulnerability |

| Banana Beach Viewpoint | Symbolic Documental Scenic | Rank I Rank II Rank III | 1st | Natural vulnerability |

| São Joaquim Viewpoint | Scenic | Rank III | 2nd | Natural vulnerability Anthropogenic Vulnerability |

| Oquê Daniel (Salaszoy) Viewpoint | Scenic | Rank III | 3rd | Natural vulnerability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neto, K.; Henriques, M.H. The Geological Heritage of Príncipe Island (West Africa). Geosciences 2025, 15, 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15090350

Neto K, Henriques MH. The Geological Heritage of Príncipe Island (West Africa). Geosciences. 2025; 15(9):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15090350

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeto, Keynesménio, and Maria Helena Henriques. 2025. "The Geological Heritage of Príncipe Island (West Africa)" Geosciences 15, no. 9: 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15090350

APA StyleNeto, K., & Henriques, M. H. (2025). The Geological Heritage of Príncipe Island (West Africa). Geosciences, 15(9), 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15090350