The Hole in the Pacific LLVP and Multipathed SKS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Waveform Data

| Event ID | Date | Longitude (°) | Latitude (°) | Depth (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 29 July 2011 | 179.92 | −23.78 | 538.95 |

| B | 21 February 2011 | 178.47 | −25.95 | 567.48 |

| C | 19 July 2014 | −174.18 | −15.64 | 233.8 |

| D | 25 April 2021 | −176.87 | −21.71 | 247.63 |

2.2. Multipathing Patterns

3. Results

3.1. Mega-ULVZ Model

3.2. Lower Mantle High-Velocity Block Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Sensitivity Tests on Geometry and Velocity of the High-Velocity Anomaly

4.2. Three-Dimensional Structure of the Lower Mantle Anomaly

4.3. SKS Multipathing on the Identification of the Mega-ULVZ

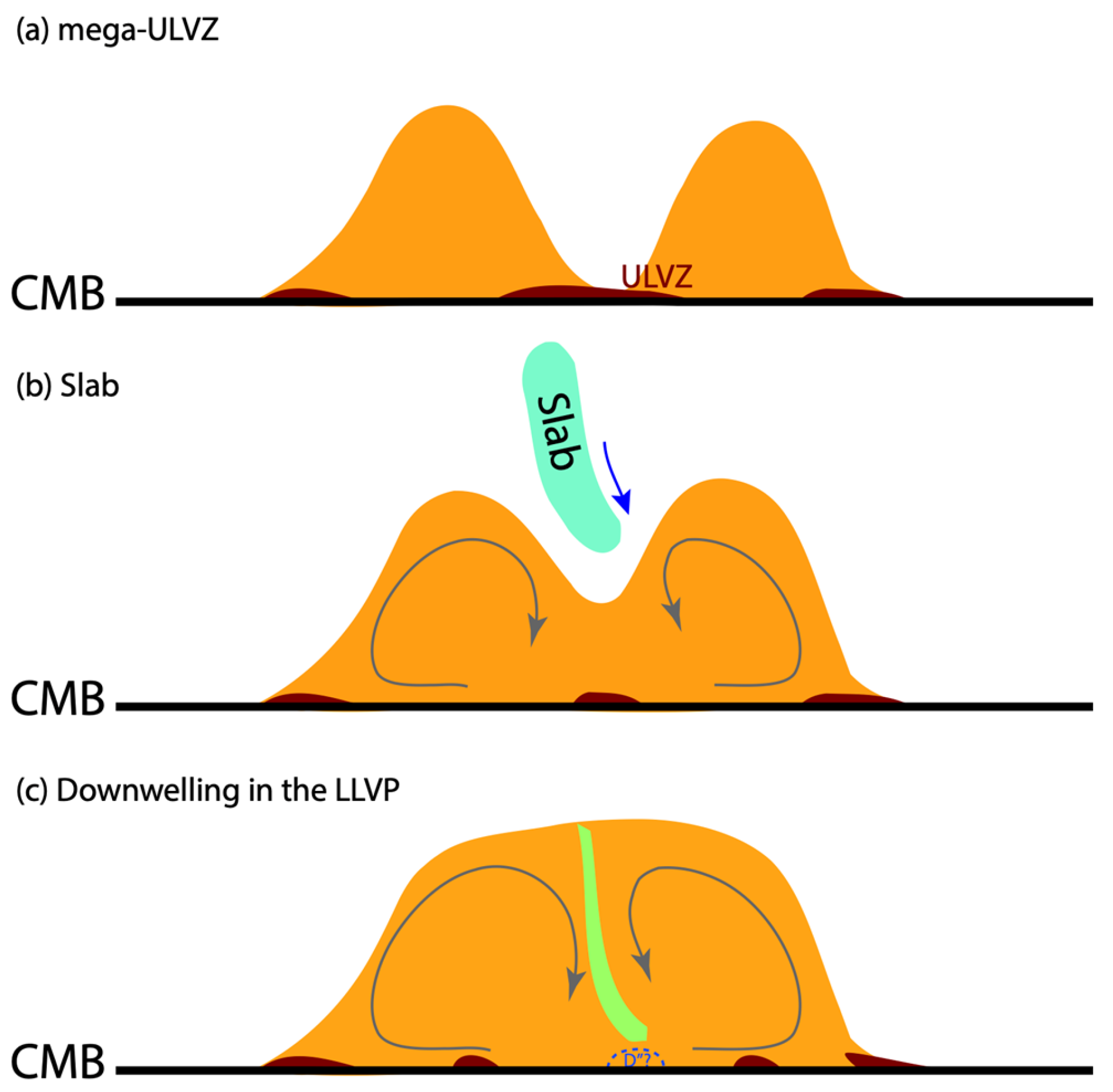

4.4. Mechanisms for Developing the LLVP Hole

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ishii, M.; Tromp, J. Normal-mode and free-air gravity constraints on lateral variations in velocity and density of Earth’s mantle. Science 1999, 285, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritsema, J.; Deuss, A.; van Heijst, H.J.; Woodhouse, J.H. S40RTS: A degree-40 shear-velocity model for the mantle from new Rayleigh wave dispersion, teleseismic traveltime and normal-mode splitting function measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 184, 1223–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Lei, W.; Liu, Q.; Peter, D.; Bozdag, E.; Tromp, J.; Hill, J.; Podhorszki, N.; Pugmire, D. GLAD-M35: A joint P and S global tomographic model with uncertainty quantification. Geophys. J. Int. 2024, 239, 478–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, K.; Sigloch, K.; Tsekhmistrenko, M.; Zaheri, A.; Nissen-Meyer, T.; Igel, H. Global mantle structure from multifrequency tomography using P, PP and P-diffracted waves. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 220, 96–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Grand, S.P.; Lai, H.Y.; Garnero, E.J. TX2019slab: A New P and S Tomography Model Incorporating Subducting Slabs. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2019, 124, 11549–11567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, N.A.; Forte, A.M.; Boschi, L.; Grand, S.P. GyPSuM: A joint tomographic model of mantle density and seismic wave speeds. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115, B12310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.W.; Romanowicz, B. Broad plumes rooted at the base of the Earth’s mantle beneath major hotspots. Nature 2015, 525, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, G.; Laske, G.; Bolton, H.; Dziewonski, A.M. The relative behavior of shear velocity, bulk sound speed, and compressional velocity in the mantle: Implications for chemical and thermal structure. In Earth’s Deep Interior: Mineral Physics and Tomography from the Atomic to the Global Scale; Geophysical Monograph Series; Karato, S., Forte, A., Liebermann, R., Masters, G., Stixrude, L., Eds.; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Volume 117, pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Koelemeijer, P.; Ritsema, J.; Deuss, A.; van Heijst, H.J. SP12RTS: A degree-12 model of shear- and compressional-wave velocity for Earth’s mantle. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 204, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, C.; Masters, G.; Shearer, P.; Laske, G. Shear and compressional velocity models of the mantle from cluster analysis of long-period waveforms. Geophys. J. Int. 2008, 174, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, L.X. Geometry and P and S velocity structure of the “African Anomaly”. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2007, 112, B05313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmberger, D.V.; Ni, S.D. Seismic modeling constraints on the South African Super Plume. In Earth’s Deep Mantle: Structure, Composition, and Evolution; Geophysical Monograph Series; van der Hilst, R.D., Bass, J.D., Matas, J., Trampert, J., Eds.; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 160, pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.M.; Wen, L.X. Structural features and shear-velocity structure of the “Pacific Anomaly”. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2009, 114, B02309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.M.; Wen, L.X. Geographic boundary of the “Pacific Anomaly” and its geometry and transitional structure in the north. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2012, 117, B09308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munch, F.D.; Romanowicz, B.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Rudolph, M.L. Deep mantle plumes feeding periodic alignments of asthenospheric fingers beneath the central and southern Atlantic Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2407543121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekic, V.; Cottaar, S.; Dziewonski, A.; Romanowicz, B. Cluster analysis of global lower mantle tomography: A new class of structure and implications for chemical heterogeneity. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 357, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottaar, S.; Lekic, V. Morphology of seismically slow lower-mantle structures. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 207, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lekic, V.; Schmerr, N.C.; Gu, Y.J.; Guo, Y.; Lin, R. Mesozoic intraoceanic subduction shaped the lower mantle beneath the East Pacific Rise. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Zhang, B.L.; Sun, D.Y.; Tian, D.D.; Yao, J.Y. Detailed 3D Structures of the Western Edge of the Pacific Large Low Velocity Province. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2024, 129, e2023JB028032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Gurnis, M. Metastable superplumes and mantle compressibility. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L20307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Tan, E.; Helmberger, D.; Gurnis, M. Seismological support for the metastable superplume model, sharp features, and phase changes within the lower mantle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 9151–9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, M.S.; Garnero, E.J.; Jahnke, G.; Igel, H.; McNamara, A.K. Mega ultra low velocity zone and mantle flow. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 364, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Gurnis, M. Compressible thermochemical convection and application to lower mantle structures. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2007, 112, B06304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, A.K. A review of large low shear velocity provinces and ultra low velocity zones. Tectonophysics 2019, 760, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, A.K.; Garnero, E.J.; Rost, S. Tracking deep mantle reservoirs with ultra-low velocity zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 299, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.L.; Garnero, E.J. Ultralow Velocity Zone Locations: A Global Assessment. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2018, 19, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottaar, S.; Romanowicz, B. An unsually large ULVZ at the base of the mantle near Hawaii. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 355, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Sun, D.Y.; Bower, D.J. Slab control on the mega-sized North Pacific ultra-low velocity zone. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Leng, K.D.; Jenkins, J.; Cottaar, S. Kilometer-scale structure on the core-mantle boundary near Hawaii. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, A.; Fukao, Y.; Tsuboi, S. Evidence for a thick and localized ultra low shear velocity zone at the base of the mantle beneath the central Pacific. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2011, 184, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.; Mousavi, S.; Li, Z.; Cottaar, S. A high-resolution map of Hawaiian ULVZ morphology from ScS phases. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2021, 563, 116885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, V.H.; Helmberger, D.; Dobrosavljevic, V.V.; Wu, W.B.; Sun, D.Y.; Jackson, J.M.; Gurnis, M. Strong ULVZ and Slab Interaction at the Northeastern Edge of the Pacific LLSVP Favors Plume Generation. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2022, 23, e2021GC010020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Helmberger, D.; Lai, V.H.; Gurnis, M.; Jackson, J.M.; Yang, H.Y. Slab Control on the Northeastern Edge of the Mid-Pacific LLSVP Near Hawaii. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 3142–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Sun, X.L.; Thomas, C. Localized ultra-low velocity zones at the eastern boundary of Pacific LLSVP. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2019, 507, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, D.J.; Gurnis, M.; Seton, M. Lower mantle structure from paleogeographically constrained dynamic Earth models. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2013, 14, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackley, P.J. Dynamics and evolution of the deep mantle resulting from thermal, chemical, phase and melting effects. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2012, 110, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Leng, W.; Zhong, S.J.; Gurnis, M. On the location of plumes and lateral movement of thermochemical structures with high bulk modulus in the 3-D compressible mantle. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2011, 12, Q07005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, N.A.; Myers, S.C.; Johannesson, G.; Matzel, E. LLNL-G3Dv3: Global P wave tomography model for improved regional and teleseismic travel time prediction. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2012, 117, B10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Grand, S.P. The effect of subducting slabs in global shear wave tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 205, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondenay, S.; Cormier, V.F.; Van Ark, E.M. SKS and SPdKS sensitivity to two-dimensional ultralow-velocity zones. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115, B04311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmberger, D.V.; Garnero, E.J.; Ding, X. Modeling two-dimensional structure at the core-mantle boundary. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1996, 101, 13963–13972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnero, E.J.; Helmberger, D.V. A very slow basal layer underlying large-scale low-velocity anomalies in the lower mantle beneath the pacific—Evidence from core phases. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 1995, 91, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnero, E.J.; Helmberger, D.V. Seismic detection of a thin laterally varying boundary layer at the base of the mantle beneath the central-Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1996, 23, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondenay, S.; Fischer, K.M. Constraints on localized core-mantle boundary structure from multichannel, broadband SKS coda analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2003, 108, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnero, E.J.; Helmberger, D.V. Further structural constraints and uncertainties of a thin laterally varying ultralow-velocity layer at the base of the mantle. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1998, 103, 12495–12509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmberger, D.V.; Wen, L.; Ding, X. Seismic evidence that the source of the Iceland hotspot lies at the core-mantle boundary. Nature 1998, 396, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.X.; Helmberger, D.V. A two-dimensional P-SV hybrid method and its application to modeling localized structures near the core-mantle boundary. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1998, 103, 17901–17918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanacore, E.A.; Rost, S.; Thorne, M.S. Ultralow-velocity zone geometries resolved by multidimensional waveform modelling. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 206, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, M.S.; Garnero, E.J. Inferences on ultralow-velocity zone structure from a global analysis of SPdKS waves—Art. no. B08301. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2004, 109, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, M.S.; Leng, K.D.; Pachhai, S.; Rost, S.; Wicks, J.; Nissen-Meyer, T. The Most Parsimonious Ultralow-Velocity Zone Distribution From Highly Anomalous SPdKS Waveforms. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2021, 22, e2020GC009467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, M.S.; Pachhai, S.; Leng, K.D.; Wicks, J.K.; Nissen-Meyer, T. New Candidate Ultralow-Velocity Zone Locations from Highly Anomalous SPdKS Waveforms. Minerals 2020, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, M.S.; Takeuchi, N.; Shiomi, K. Melting at the Edge of a Slab in the Deepest Mantle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 8000–8008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachhai, S.; Li, M.M.; Thorne, M.S.; Dettmer, J.; Tkalcic, H. Internal structure of ultralow-velocity zones consistent with origin from a basal magma ocean. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.E.; Garnero, E.J.; Li, M.M.; Shim, S.H.; Rost, S. Globally distributed subducted materials along the Earth’s core-mantle boundary: Implications for ultralow velocity zones. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.J.; Thorne, M.S.; Rost, S. SPdKS analysis of ultralow-velocity zones beneath the western Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 4574–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.W.; Helmberger, D.V.; Li, D.Z. Imaging subducted slab structure beneath the Sea of Okhotsk with teleseismic waveforms. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2014, 232, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.Y.; Helmberger, D. Upper-mantle structures beneath USArray derived from waveform complexity. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 184, 416–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.Y.; Gurnis, M.; Saleeby, J.; Helmberger, D. A dipping, thick segment of the Farallon Slab beneath central U.S. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 2911–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sun, D.Y. A Lower Mantle Slab Below the East Asia Margin Constrained by Seismic Waveform Complexity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2022JB024246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.Y.T.; Helmberger, D.V.; Wang, H.L.; Zhan, Z.W. Lower Mantle Substructure Embedded in the Farallon Plate: The Hess Conjugate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 10216–10225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennett, B.L.N.; Engdahl, E.R. Traveltimes for global earthquake location and phase identification. Geophys. J. Int. 1991, 105, 429–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, G.; Nettles, M.; Dziewonski, A.M. The global CMT project 2004-2010: Centroid-moment tensors for 13,017 earthquakes. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2012, 200, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewonski, A.M.; Chou, T.A.; Woodhouse, J.H. Determination of earthquake source parameters from waveform data for studies of global and regional seismicity. J. Geophys. Res. 1981, 86, 2825–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.Y.; Helmberger, D.V.; Jackson, J.M.; Clayton, R.W.; Bower, D.J. Rolling hills on the core-mantle boundary. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 361, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.Y.; Helmberger, D.; Ni, S.D.; Bower, D. Direct measures of lateral velocity variation in the deep Earth. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2009, 114, B05303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand, S.P.; Helmberger, D.V. Upper mantle shear structure of north-america. Geophys. J. R. Astron. Soc. 1984, 76, 399–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bréger, L.; Romanowicz, B. Three-dimensional structure at the base of the mantle beneath the central Pacific. Science 1998, 282, 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, J.; Müller, G. Anomalous difference traveltimes and amplitude ratios of SKS and SKKS from Tonga-Fiji Events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1986, 13, 1529–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, J. Untersuchungen zur Geschwindigkeitsstruktur im unteren Erdmantel und im Bereich der Kern-Mantel-Grenze unterhalb des Pazifiks mit Scherwellen. Ph.D. Thesis, Frankfurt University, Frankfurt, Germany, 1990; p. 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, J. Laufzeiten und Amplituden der Phasen SKS und SKKS und die Struktur des äußeren Erdkerns. Ph.D. Thesis, der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University, Frankfurt, Germany, 1984; p. 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Z.; Helmberger, D.; Clayton, R.W.; Sun, D.Y. Global synthetic seismograms using a 2-D finite-difference method. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 197, 1166–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmandt, B.; Lin, F.C. P and S wave tomography of the mantle beneath the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 6342–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, R.S.; Schmandt, B.; Helmberger, D.V. Juan de Fuca subduction zone from a mixture of tomography and waveform modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2012, 117, B03304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festin, M.M.; Thorne, M.S.; Li, M. Evidence for Ultra-Low Velocity Zone Genesis in Downwelling Subducted Slabs at the Core– Mantle Boundary. Seism. Rec. 2024, 4, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatitsch, D.; Xie, Z.N.; Bozdag, E.; de Andrade, E.S.; Peter, D.; Liu, Q.Y.; Tromp, J. Anelastic sensitivity kernels with parsimonious storage for adjoint tomography and full waveform inversion. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 206, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.D.; Tan, E.; Gurnis, M.; Helmberger, D. Sharp sides to the African superplume. Science 2002, 296, 1850–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.M.; McNamara, A.K.; Garnero, E.J.; Yu, S.L. Compositionally-distinct ultra-low velocity zones on Earth’s core-mantle boundary. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Long, M.D.; Frost, D.A. Ultralow velocity zone and deep mantle flow beneath the Himalayas linked to subducted slab. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zong, J. From Subduction to LLSVP: The Core-Mantle Boundary Heterogeneities Across North Atlantic. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2022, 23, e2021GC009879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuru, K.; Kawai, K.; Geller, R.J. Subducted Slab Slipping Underneath the Northern Edge of the Pacific Large Low-Shear-Velocity Province in D”. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2025, 130, e2024JB030654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Ni, S.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, M.; Sun, H.; Hou, M.; Cui, X.; Sun, D. Detections of ultralow velocity zones in high-velocity lowermost mantle linked to subducted slabs. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davaille, A.; Romanowicz, B. Deflating the LLSVPs: Bundles of Mantle Thermochemical Plumes Rather Than Thick Stagnant “Piles”. Tectonics 2020, 39, e2020TC006265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.A.; Rost, S. The P-wave boundary of the Large-Low Shear Velocity Province beneath the Pacific. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014, 403, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, A.K.; Zhong, S. Thermochemical structures beneath Africa and the Pacific Ocean. Nature 2005, 437, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Gurnis, M.; Jackson, J.M. Influence of subduction history and mineral deformation on seismic anisotropy in the lower mantle. Geophys. J. Int. 2025, ggaf457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Li, M. Vastly Different Heights of LLVPs Caused by Different Strengths of Historical Slab Push. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL099564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Helmberger, D.; Song, X.D.; Grand, S.P. Predicting a Global Perovskite and Post-Perovskite Phase Boundary. In Post-Perovskite: The Last Mantle Phase Transition; Geophysical Monograph Series; Hirose, K., Lay, T., Yuen, D., Eds.; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Volume 174, pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, D. The Hole in the Pacific LLVP and Multipathed SKS. Geosciences 2025, 15, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120471

Sun D. The Hole in the Pacific LLVP and Multipathed SKS. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120471

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Daoyuan. 2025. "The Hole in the Pacific LLVP and Multipathed SKS" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120471

APA StyleSun, D. (2025). The Hole in the Pacific LLVP and Multipathed SKS. Geosciences, 15(12), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120471