Integrating PCA and Fractal Modeling for Identifying Geochemical Anomalies in the Tropics: The Malang–Lumajang Volcanic Arc, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geology and Mineralization of the Research Area

2.1. Geology

2.2. Geological Controls for Mineralization

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Analysis Methods

3.3. Statistical Analysis Methods

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA):

- Mean + 2Standard Deviation (SD) and Median + 2Median Absolute Deviation (MAD):

- Concentration–Area (C–A) Fractal Model:

3.4. Methodology Workflow

4. Result

4.1. Secondary and Primary Data

4.2. Stream Sediment Geochemical Data

4.3. Rock Geochemical Analysis

4.4. Statistical Parameter Analysis

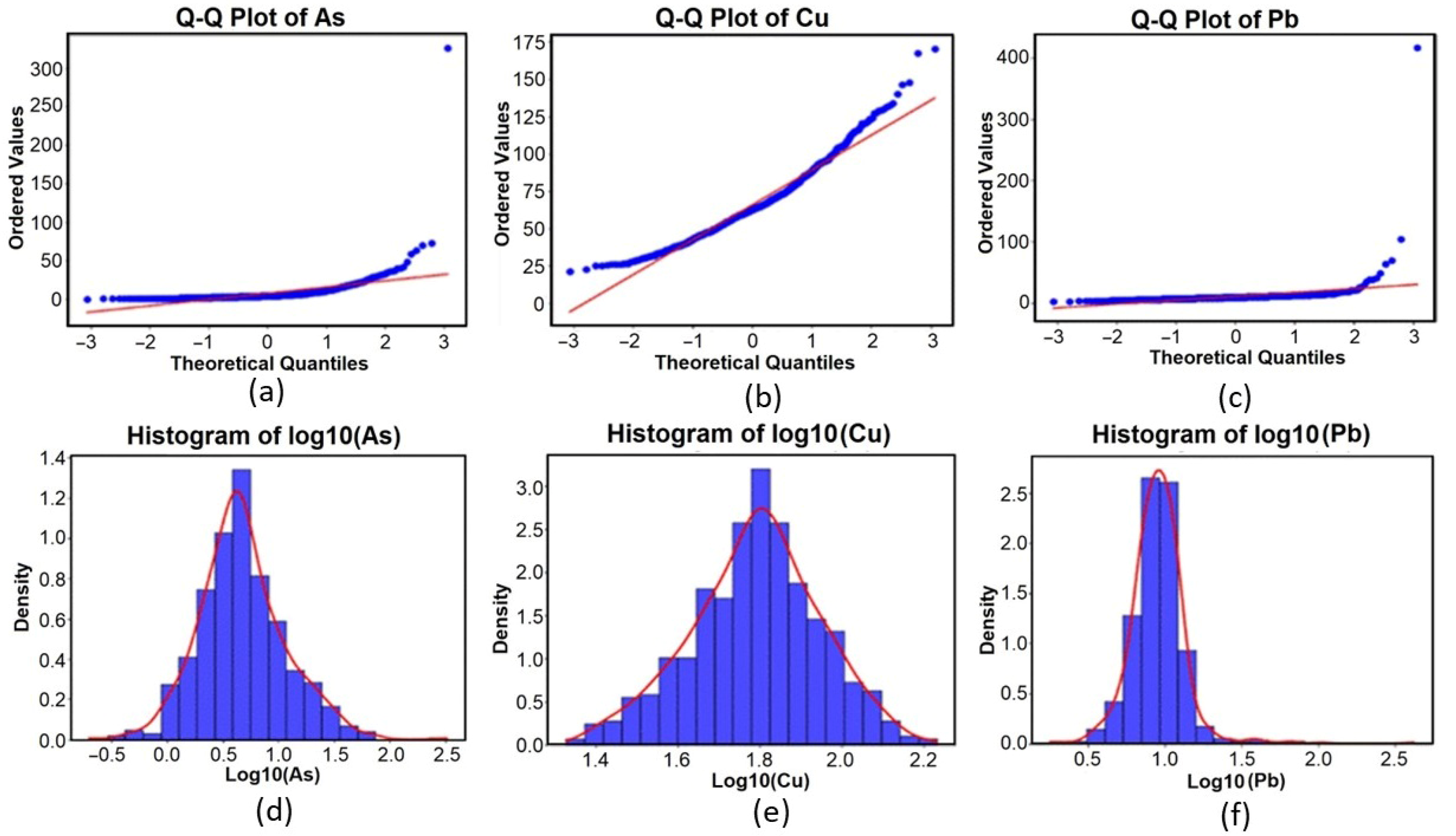

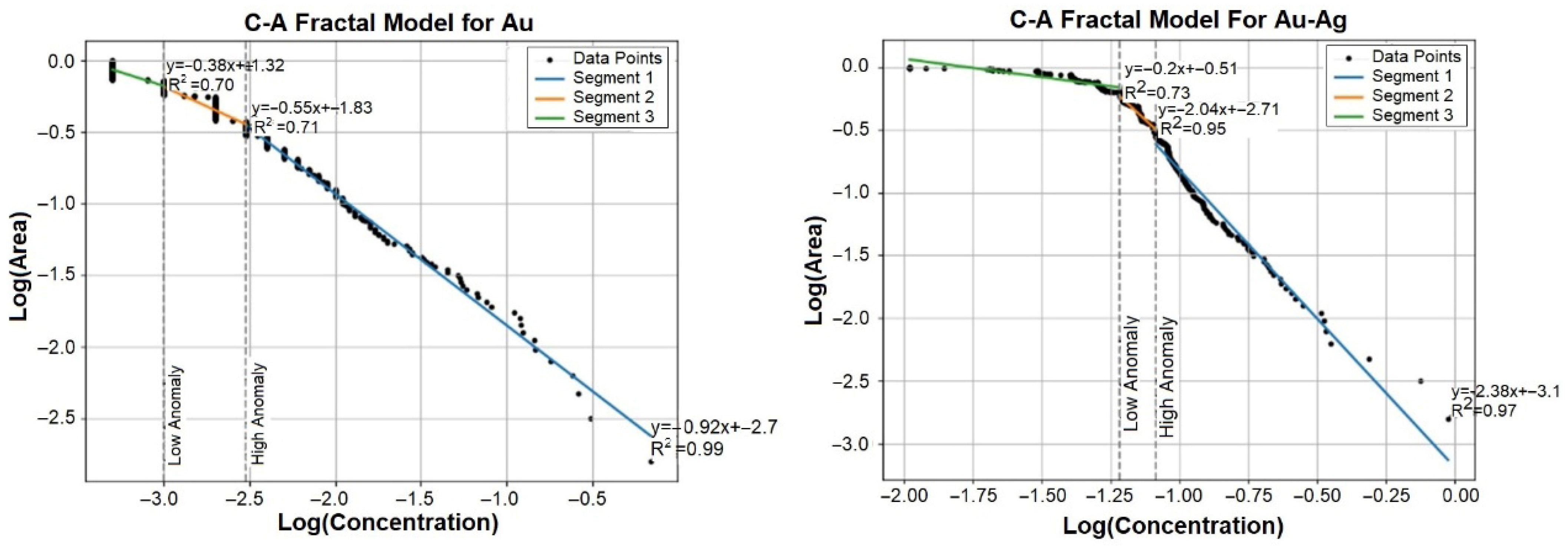

4.5. Anomaly Threshold Value Analysis

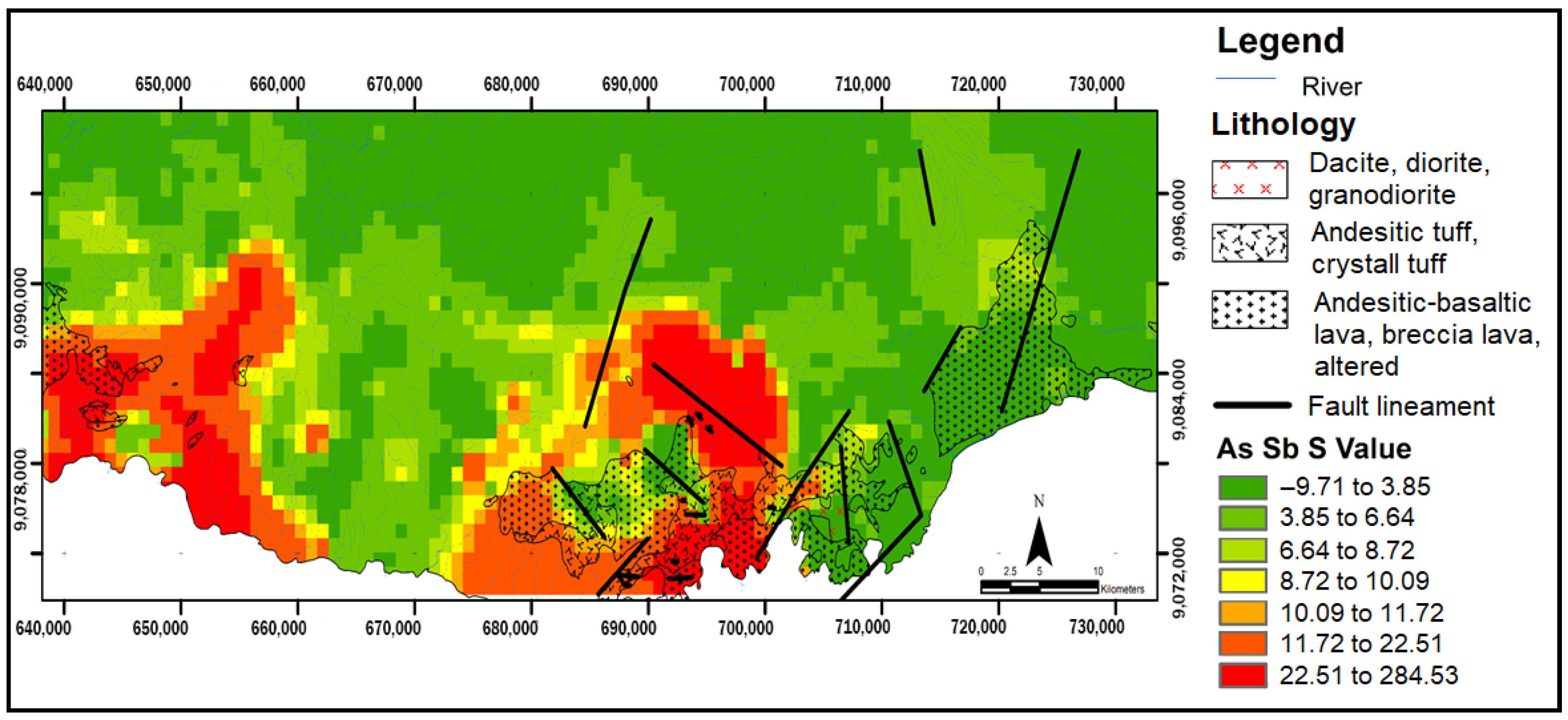

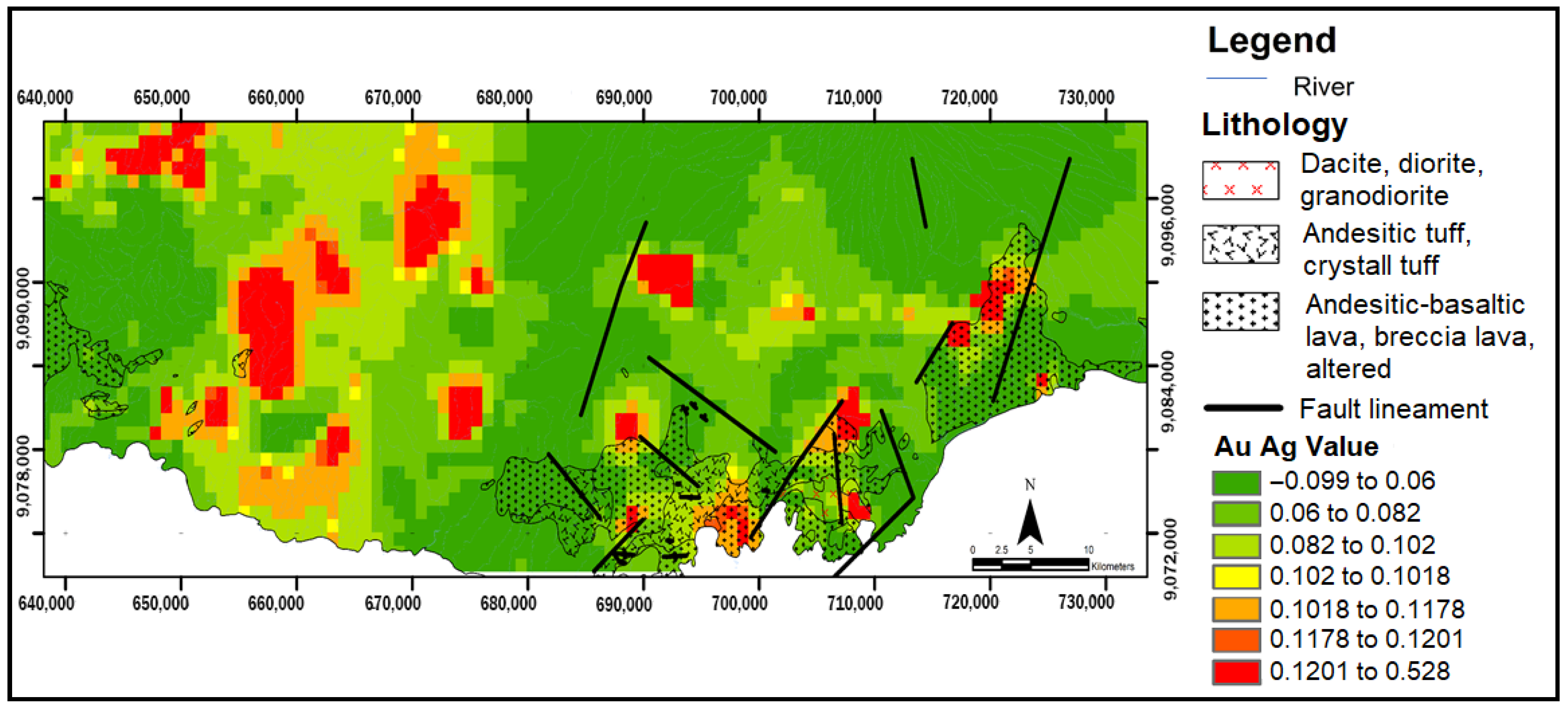

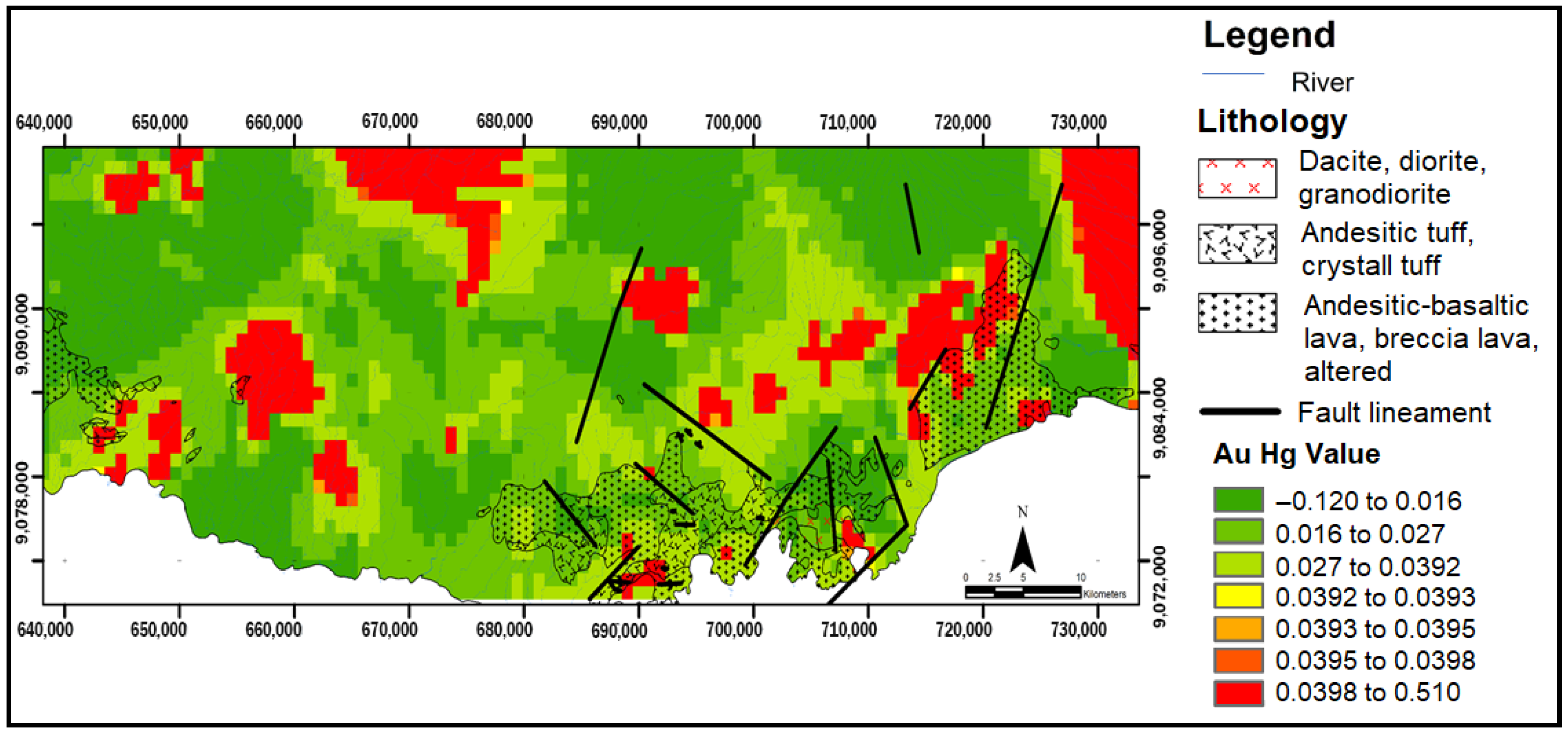

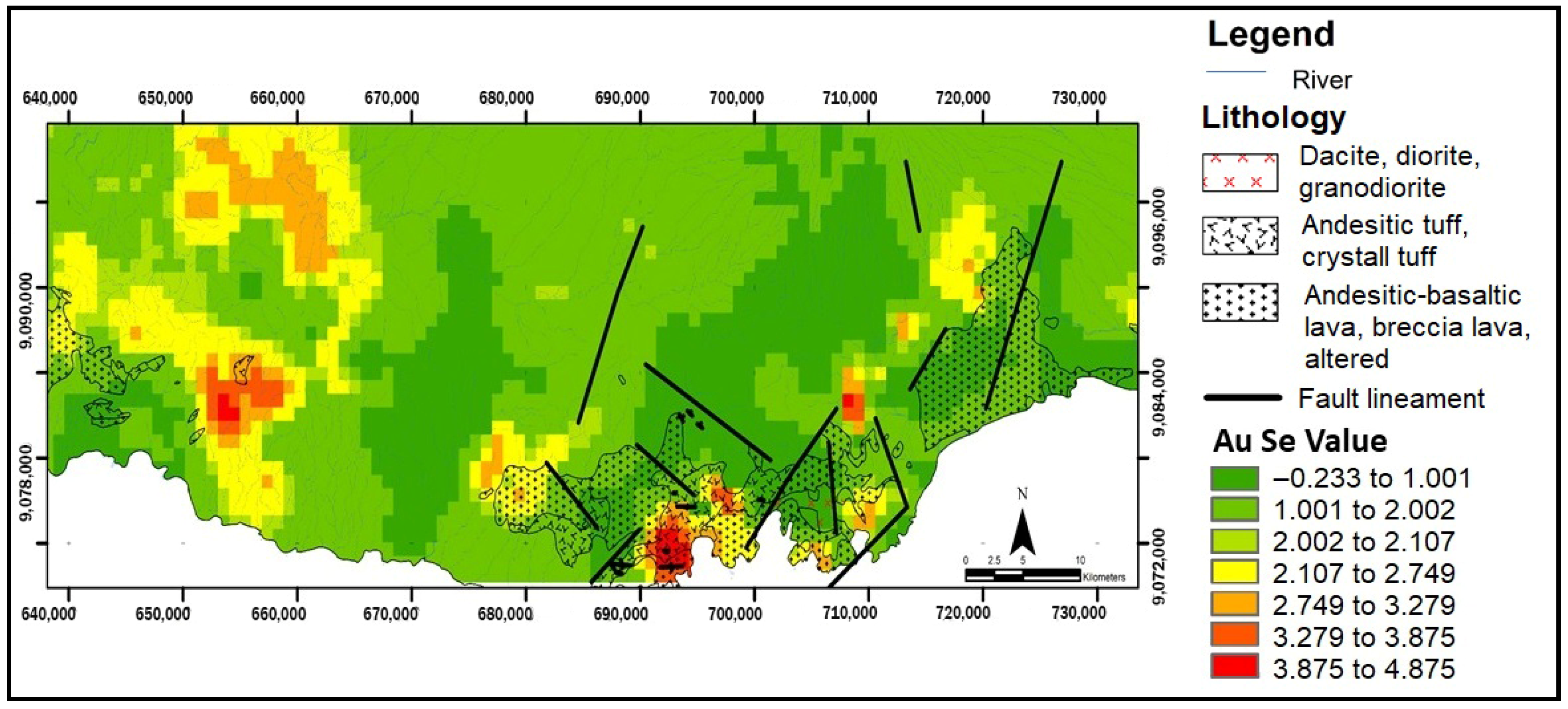

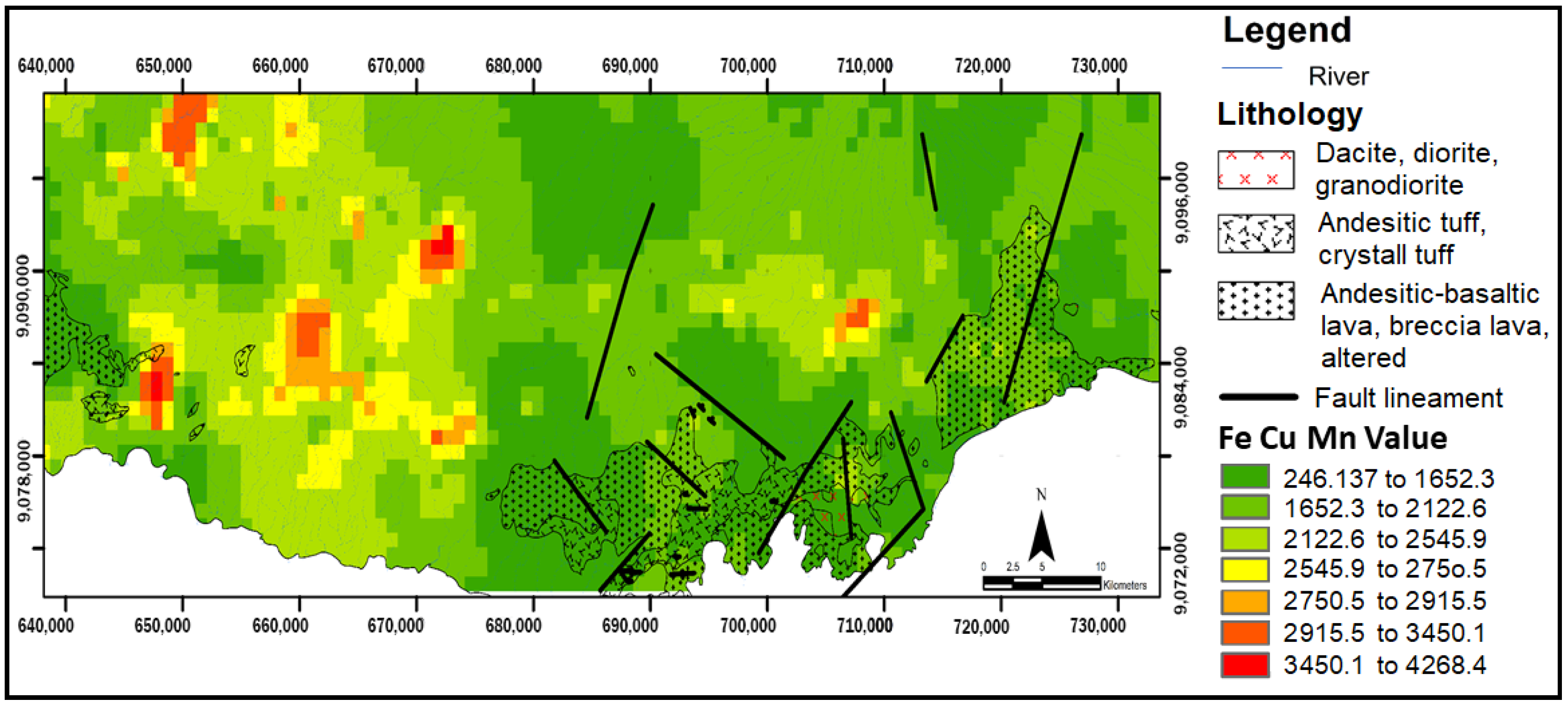

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Effectiveness of Methods

5.2. Multi-Element Associations and Mineralization Styles

5.3. Practical Implications for Exploration

- Advance the southern corridor (690,000–710,000 E; 9,078,000–9,084,000 N) to drill-ready status immediately. Support this process with focused geophysics and detailed alteration mapping.

- Initiate systematic geochemical and structural surveys in the eastern extension (715,000–725,000 E; 9,082,000–9,090,000 N), where Au–Ag and Au–Hg anomalies indicate a structurally controlled corridor. Complete these steps before drilling begins. The methods section, including sampling techniques, analytical procedures, and static analysis methods, must be thoroughly detailed.

- Integrate geochemistry with geophysics in the western dispersion zone (650,000–660,000 E; 9,078,000–9,090,000 N) to delineate feeder structures and vector toward concealed systems at depth.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

- Low to high sulfidation epithermal Au–Ag systems—where “epithermal” refers to mineral deposits formed by hot fluids near the Earth’s surface and “low- to high-sulfidation” describes the amount and type of sulfur involved in forming the minerals. The association of Au (gold), Ag (silver), Hg (mercury), Se (selenium), Sb (antimony), and As (arsenic) occurs in volcanic and brecciated (broken) host rocks, reflecting volatile-rich magmatic–hydrothermal activity occurring in shallow parts of the crust.

- Porphyry systems, which are large mineral deposits associated with porphyritic intrusive rocks (rocks containing large crystals), are reflected by Fe (iron), Cu (copper), and Mn (manganese) and Au–Pb (gold–lead) enrichments along intrusive rock boundaries and deeper fluid pathways. These geochemical patterns are consistent with vein-type hydrothermal systems.

6.2. Recommendations for Exploration Are as Follows

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, C.; Xu, Z.; Duan, M.; Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Wei, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L. Genetic model of the Luhai sandstone-type uranium deposit: Insights from sedimentological and geochemical evidence. Minerals 2025, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngozi-Chika, C.S.; Mhlongo, S.E. Mapping and analysis of stream sediment heavy mineral fractions for mineral exploration: A case study of a portion of North-Central Nigeria. Discov. Miner. 2025, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdeau, J.E.; Zhang, S.E.; Nwaila, G.T.; Ghorbani, Y. Data generation for exploration geochemistry: Past, present, and future perspectives. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 161, 106124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidder, J.A.; Garrett, R.G.; McClenaghan, M.B.; Beckett-Brown, C.E.; Day, S.J.A. Exploration Hydrogeochemistry: Case Studies 1935 to 2024 (Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 9186); Geochemistry: Exploration, Environment, Analysis; Natural Resources Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024; Volume 12, pp. 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, M.E.; Arndtm, K.; Chang, Z.; Kelley, K.; Lavin, O. Stream sediment geochemistry in mineral exploration: A review of fine-fraction, Clay-fraction, Bulk leach gold, Heavy mineral concentrate and indicator mineral chemistry. Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 2023, 23, geochem2022-039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency and Metal Mining of Japan. Phase 2 Report on the Mineral Exploration in the East Java Area; Refs. Indonesia, Unpublished Internal Report; Japan International Cooperation Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sidorov, A.A.; Volkov, A.V.; Savva, N.E. Volcanism and epithermal deposits. J. Volcanol. Seismol. 2015, 9, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, L.R.; Guarino, A.; Iannone, A.; Albanese, S. Accounting for the compositional nature of geochemical data to improve the interpretation of their univariate and multivariate spatial patterns: A case study from the Campania region (Italy). Geosciences 2025, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahrazeh, M.G.; You, H. Systematic Geochemical Exp Sediments for Gol Area (SE Zahedan). J. Biochem. Technol. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Urzola, R.; Van Deun, K.; Vera, J.C.; Sijtsma, K. A Guide for Sparse PCA: Model Comparison and Applications. Psychometrika 2021, 86, 893–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, M.; Haji, B.A.; Daya, A.; Manouchehriniya, M. Separating geochemical anomalies by concentration-area, concentration-perimeter, and concentration-number fractal models in the Qaen region, East of Iran. Iran. J. Earth Sci. 2021, 14, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nforba, M.T.; Egbenchung, K.A.; Berinyuy, N.L.; Mimba, M.E.; Tangko, E.T.; Nono, G.D.K. Statistical evaluation of stream sediment geochemical data from Tchangue-Bikoui drainage system, Southern Cameroon: A regional perspective. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2020, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katili, J.A. Evolution of the Southeast Asian arc complex. Geol. Indones. 1989, 12, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Soeria Atmadja, R.; Maury, R.C.; Bellon, H.; Pringgoprawiro, H.; Polve, M.; Priadi, B. Tertiary magmatic belts in Java. J. Southeast Asian Earth Sci. 1994, 9, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulja, T.; Heriawan, M.N.; Hawu Hede, A.N. Porphyry and skarn Cu prospectivity of Sumatra with GIS spatial modelling techniques. Appl. Earth Sci. 2024, 133, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, M.D.; Yudha, R.A.M.; Watania, O.M.L.; Wiloso, D.A. Characteristics and paragenesis of porphyry copper deposit in Sidomulyo, Trenggalek, East Java: Multiple intrusions, hydrothermal alteration, and vein association. Indones. J. Econ. Geol. (IJEG) 2025, 1, 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.-Z.; Gao, W.-S.; Deng, X.-D. Geology and geochronology of magmatic-hydrothermal breccia pipes in the Yixingzhai gold deposit: Implications for ore genesis and regional exploration. Minerals 2024, 14, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, T.C.; Ratman, N.; Gafoer, S. Peta Geologi Lembar Jawa Bagian Tengah. Skala 1: 500.000; Puslitbang Geologi; Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral: Bandung, Indonesia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency and Metal Mining of Japan. Phase 3 Report on The Mineral Exploration in the East Java Area; Indonesia, Unpublished Internal Report; Japan International Cooperation Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gafoer, S.; Ratman, N. Peta Geologi Regional Jawa Bagian Timur, Skala 1: 500.000; Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Geologi; Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral: Bandung, Indonesia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wartono, R.; Rumidi, S.; Rosidi, H.M.D. Peta Geologi Lembar Yogyakarta, Jawa, Skala 1: 100000; Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Geologi; Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral: Bandung, Indonesia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Samodera, H.; Suharsono, S.G.; Suwarti, T. Peta Geologi Lembar Tulungagung Skala 1: 100.000; Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Geologi; Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral: Bandung, Indonesia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sutarto, S.; Idrus, A.; Harijoko, A.; Setijadji, L.D.; Sindern, S. Mineralization style of the Randu Kuning porphyry Cu–Au and intermediate sulphidation epithermal Au–base metals deposits at Selogiri area, Central Java, Indonesia. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2245, 020050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulunggono, A.; Martodjojo, S. The Tectonic Changes During Paleogene-Neogene were the Most Important Tectonic Phenomenon in Java Island. In Proceedings of the Seminar on Geology and Tectonics of Java Island, from the Late Mesozoic to Quaternary; Geology and Tectonics of Java Island, from the Late Mesozoic to Quaternary Conference; Universitas Gajah Mada: Yogyakarta, Indonesia; 1994, pp. 1–14.

- Sjarifudin, M.Z.; Hamidi, S. Geology of the Blitar Quadrangle, Jawa (Quad. 1507-6), 1: 100.000; Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Geologi; Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral: Bandung, Indonesia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sujanto, R.; Hadisantono, R.; Chaniago, R.; Baharuddin, R. Geological Map of The Turen Quadrangle, Jawa; Geological Research and Development Centre: Bandung, Indonesia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Suwarti, T.; Suharsono. Geological Map of the Lumajang Quadrangle, Jawa, 1607-5; Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral: Bandung, Indonesia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bemmelen, R.W. General Geology of Indonesia and adjacent archipelagos. In The Geology of Indonesia; Government Printing Office: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Surono, B.T.; Sudarno, I.; Wiryosujono, S. Geology of the Surakarta Giritontro Quadrangles, Java; Geological Research and Development Center: Bandung, Indonesia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, D.I.; Santosh, M.; Müller, D.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Yang, L.Q.; Wang, Q.F. Mineral systems: Their advantages in terms of developing holistic genetic models and for target generation in global mineral exploration. Geosyst. Geoenviron 2022, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, D.I.; Santosh, M. Mineral Systems, Earth Evolution, and Global Metallogeny; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.P. Magmatic to hydrothermal metal fluxes in convergent and collided margins. Ore Geol. Rev. 2011, 40, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, M.; Smith, D.J.; Jenkin, G.R.; Holwell, D.A.; Dye, M.D. A review of Te and Se systematics in hydrothermal pyrite from precious metal deposits: Insights into ore-forming processes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 96, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, J.J.; Keith, M.; Haase, K.M.; Sporer, C.; Bach, W.; Klemd, R.; Strauss, H.; Storch, B.; Peters, C.; Rubin, K.H.; et al. Spatial variations in magmatic volatile influx and fluid boiling in the submarine hydrothermal systems of niuatahi caldera, Tonga rear-arc. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2022, 23, e2021GC010259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemley, J.J.; Hunt, J.P. Hydrothermal ore-forming processes in the light of studies in rock-buffered systems; II, Some general geologic applications. Econ. Geol. 1992, 87, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenquist, J.W.; Lowenstern, J.B. The role of magmas in the formation of hydrothermal ore deposits. Nature 1994, 370, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sanderson, D.J. Numerical modelling of the effects of fault slip on fluid flow around extensional faults. J. Struct. Geol. 1996, 18, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Gao, Z.; Fan, T.; Niu, Y.; Gou, R. Volcanic events—Related hydrothermal dolomitization and silicification controlled by intra-cratonic strike slip fault systems: Insights from the northern slope of the Tazhong Uplift, Tarim Basin, China. Basin Res. 2021, 33, 2411–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiatso Yimgnia, T.; Takodjou Wambo, J.D.; Ntouala, R.F.D.; Mvondo Ondoa, J. Spatial modelling of multi-element associations from stream sediment in the Lingbim-Zimbi area (Boden district, Eastern Cameroon). Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefelová, N.; Palarea-Albaladejo, J.; Hron, K.; Gába, A.; Dygrýn, J. Compositional PLS biplot based on pivoting balances: An application to explore the association between 24-h movement behaviours and adiposity. Comput. Stat. 2024, 39, 835–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, K.; Zeng, M. Vintage factor analysis with Varimax performs statistical estimation in latent variable models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2023, 85, 1037–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstykh, N.; Bortnikov, N.; Zhukova, I.; Stepanov, A.; Palyanova, G.; Shapovalova, M.; Zhao, K. Trace elements in pyrite from AuAg epithermal deposits of Kamchatka, Russia: Comparison with geochemical features of mineral systems. J. Geochem. Explor. 2025, 275, 107774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V.; Batra, N.; Poonam, G.S.; Kaur, A.; Dudekula, K.V.; Victor, J.G. Machine-learning-based exploratory data analysis (EDA) for chronic kidney disease diagnosis. Phat. Proc. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. E 2023, 104, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Estrada, E.; Cosmes, W. Shapiro–Wilk test for skew normal distributions based on data transformations. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2019, 89, 3258–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Z.; Cui, W.; Zhao, K.; Wang, H.; Jing, H.; Cao, R. A role of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) in astrocytic Aβ clearance. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 5347–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulja, T.; Heriawan, M.N. The Miwah high sulphidation epithermal Au–Ag deposit, Aceh, Indonesia: Dynamics of hydrothermal alteration mineralization interpreted from principal component analysis of lithogeochemical data. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 147, 104988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.D.; Graham, G.E.; Lowers, H.A. Hydrothermal monazite and xenotime chemistry as genetic discriminators for intrusion-related and orogenic gold deposits: Implications for an orogenic origin of the Pogo Gold Deposit, Alaska. Miner. Depos. 2024, 59, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, G.N.; Vearncombe, J.R.; Clemens, J.D.; Day, A.; Kisters, A.F.M.; Von der Heyden, B.P. Formation of Cu–Au porphyry deposits: Hydraulic quartz veins, magmatic processes and constraints from chlorine. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 70, 1010–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelissen, M. Magmatic Minerals of the Eastern Sunda Arc, Indonesia. Master’s Thesis, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, K.; Spry, P.; McLemore, V.; Fey, D.; Anderson, E. Alkalic-Type Epithermal Gold Deposit Model: Chapter R of Mineral Deposit Models for Resource Assessment; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, T.M.; Rompo, I. High Sulfidation Au (-Ag-Cu) Deposits in Indonesia: A Review; IAGI-MGEI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; pp. 1–66. ISBN 978-979-8126-47-5. Available online: https://www.iagi.or.id/web/digital/73/Book-complete.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Li, X.; Xie, G.; Gleeson, S.A.; Mao, J.; Ye, Z.; Jin, Y. Palladium, platinum, selenium, and tellurium enrichment in the Jiguanzui–Taohuazui Cu–Au Deposit, Edong Ore District: Distribution and comparison with Cu–Mo deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 154, 105335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Ellatif, M.; Elkhateeb, S.O.; Hegab, M.A.-R.; Shebl, A.; Mohamed, G.; Mahdi, A.M. Revealing porphyry mineralization Cu–Au signatures via analyzing aeromagnetic and remote sensing data of Dara-Monqul area, Egypt. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglik, B.; Sosnal, A.; Dumańska-Słowik, M.; Toboła, T.; Dimitrova, D.; Habryn, R.; Derkowski, P.; Czupyt, Z.; Włoszczyna, M.; Markowiak, M.; et al. Constraints on ore vectoring from geochemical fingerprints of porphyry-style pyrite. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabo-Ratio, J.A.; Buena, A.E.; Villaplaza, B.R.B.; Payot, B.D.; Dimalanta, C.B.; Queaño, K.L.; Andal, E.S.; Yumul, G.P., Jr. Epithermal Mineralization of the Bonanza-Sandy Vein System, Masara Gold District, Mindanao, Philippines. J. Asian Earth Sci. X 2020, 4, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunge, M.; Espi, J.O. Trace Element Geochemistry of Chalcopyrites and Pyrites from Golpu and Nambonga North Porphyry Cu-Au Deposits, Wafi-Golpu Mineral District, Papua New Guinea. Geosciences 2021, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogonatos, C.; Voudouris, P.; Berndt, J.; Klemme, S.; Zaccarini, F.; Spry, P.G.; Melfos, V.; Tarantola, A.; Keith, M.; Klemd, R.; et al. Trace elements in magnetite from the Pagoni Rachi porphyry prospect, NE Greece: Implications for ore genesis and exploration. Minerals 2019, 9, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, P.; Ccolqque, E.; Garcia-Valles, M.; Martínez, A.; Yubero, M.T.; Anticoi, H.; Sidki-Rius, N. Mineralogy and mineral chemistry of the Au-Ag-Te-(Bi-Se) San Luis Alta deposit, mid-south Peru. Minerals 2023, 13, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shi, X.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Ye, J.; Yan, Q.; Dang, Y.; Fang, X. Biogeochemical sulfide mineralization in the volcanic-hosted Tongguan hydrothermal field, southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1562763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Z.; Yang, R.; Du, L.; Liao, M. Gold and antimony metallogenic relations and ore-forming process of Qinglong Sb(Au) deposit in Youjiang basin, SW China: Sulfide trace elements and sulfur isotopes. Geosci. Front. 2020, 12, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalova, M.; Shaparenko, E.; Tolstykh, N. Geochemistry and fluid inclusion of epithermal Au–Ag deposits in Kamchatka, Russia. Minerals 2025, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chiaradia, M.; Qin, K.Z.; Hui, K.X.; Li, Z.Z.; Cao, M.J.; Li, G.M. Magmatic Controls on Au-and Ag-Rich Intermediate-Sulfidation Epithermal Deposits from Northeast China. Econ. Geol. 2024, 119, 1913–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Rocks Environment | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alluvium | 17 | 2.67 |

| 2 | Quaternary volcanic rocks | 213 | 33.49 |

| 3 | Miocene volcanic | 102 | 16.04 |

| 4 | Miocene sedimentary rocks | 94 | 14.78 |

| 5 | Miocene Limestone | 71 | 11.16 |

| 6 | Oligocene Intrusive rocks | 8 | 1.26 |

| 7 | Oligocene volcanic rocks | 131 | 20.60 |

| Total | 636 | 100 | |

| Variable | Raw Data | Transform Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC-1 | PC-2 | PC-A | PC-B | |

| Au | 0.03 | 0.18 | −0.12 | 0.42 |

| Ag | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.42 |

| As | −0.33 | 0.42 | −0.25 | −0.46 |

| Cu | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.34 | −0.16 |

| Fe | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.02 |

| Pb | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.07 |

| S | −0.30 | 0.39 | −0.29 | 0.09 |

| Sb | −0.33 | 0.40 | −0.32 | −0.31 |

| Te | −0.23 | 0.23 | −0.21 | 0.25 |

| Zn | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.25 |

| Hg | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Mn | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.38 | −0.07 |

| Se | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.07 | −0.20 |

| Ba | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.32 | −0.41 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.28 | 2.30 | 5.19 | 1.56 |

| Proportion | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.11 |

| Cumulative | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.48 |

| No. | Sample | Area | Au | Ag | Cu | Pb | Zn | As | Sb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ng/g | µg/g | µg/g | µg/g | µg/g | µg/g | µg/g | |||

| 1 | W 031 | Purwodadi–Pujiharjo | 3 | 9 | 21,400 | 20 | 277 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | W 034 | 3 | 5 | 32,100 | 26 | 49 | 2 | 6 | |

| 3 | W 035 | 3 | 4 | 266 | 50 | 175 | 3 | 4 | |

| 4 | W 038 | 560 | 3 | 546 | 20 | 41 | 10 | 4 | |

| 5 | W 039 | 3 | 10 | 10,300 | 20 | 156 | <LD | 10 | |

| 6 | E 051 | Ngrawan | <LD | 2 | 25 | 53 | 97 | 3 | <LD |

| 7 | E052 | <LD | 2 | 110 | 56 | 183 | <LD | 2 | |

| 8 | E 055 | 177 | <LD | 669 | 43 | 190 | <LD | 4 | |

| 9 | E 056 | 174 | <LD | 502 | 37 | 165 | <LD | 4 | |

| 10 | E 063 | 133 | <LD | 53 | 53 | 29 | <LD | 4 | |

| 11 | E 066 | 102 | <LD | 520 | 39 | 130 | <LD | 4 | |

| 12 | E 067 | 114 | 3 | 498 | 42 | 242 | <LD | 4 |

| Element | Au | Ag | As | Ba | Cu | Fe | Mn | Pb | S | Sb | Se | Te | Zn | Hg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Samples | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 | 635 |

| Mean | 0.01 | 0.07 | 7.61 | 290.6 | 65.68 | 10.76 | 1788 | 10.53 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 1.49 | 0.08 | 145.53 | 0.02 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.03704 | 0.04 | 15.20 | 136.5 | 23.81 | 5.01 | 552.74 | 17.40 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 58.44 | 0.04 |

| Minimum | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 67 | 21.20 | 0.63 | 126 | 1.80 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 13 | 0.01 |

| P25 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 2.70 | 195 | 48.75 | 7.08 | 1395 | 7.20 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 112 | 0.01 |

| Median | 0.00 | 0.06 | 4.40 | 270 | 62.60 | 9.24 | 1735 | 9 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.05 | 137 | 0.02 |

| P75 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 7.65 | 370 | 77.85 | 13.53 | 2135 | 11.20 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 2 | 0.09 | 168 | 0.02 |

| P90 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 15.80 | 446 | 96.50 | 17.69 | 2470 | 13.06 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 3 | 0.16 | 208.60 | 0.03 |

| P95 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 23.18 | 493 | 111.50 | 21.16 | 2753 | 15.03 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 3 | 0.25 | 242.30 | 0.04 |

| P98 | 0.07 | 0.153 | 34.38 | 560 | 125.30 | 25 | 3063 | 21.28 | 0.36 | 0.69 | 4 | 0.35 | 289.64 | 0.05 |

| Maximum | 0.69 | 0.68 | 326 | 2010 | 170.50 | 25 | 4940 | 417 | 1.93 | 9.29 | 5 | 0.63 | 688 | 0.83 |

| Skewness | 12.60 | 5.91 | 15.12 | 3.58 | 0.89 | 1.03 | 0.75 | 20.57 | 9.98 | 16.22 | 0.81 | 3.20 | 2.64 | 19.51 |

| Kurtoses | 204.7 | 69.42 | 305.23 | 38.86 | 1.18 | 0.65 | 2.25 | 472.92 | 127.97 | 323.84 | 0.29 | 13.02 | 16.13 | 443.21 |

| Element | Mean + 2SD | Median + 2MAD | C-A Fractal Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Data | Log-Transformed Data | Raw Data | Log-Transformed Data | Low Anomaly | High Anomaly | |

| Au | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Ag | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| As | 9.89 | 22.01 | 8.60 | 11.15 | 3.80 | 6.60 |

| Ba | 511.10 | 607.69 | 432 | 506.90 | 230 | 350 |

| Cu | 108.79 | 126.86 | 91.80 | 100.68 | 58.10 | 73.50 |

| Fe | 20.77 | 23.06 | 14.76 | 17.02 | 8.31 | 12.50 |

| Mn | 2801.34 | 3387.97 | 2469 | 2664.21 | 1575 | 2040 |

| Pb | 14.57 | 16.28 | 12.80 | 13.87 | 8.40 | 10.60 |

| S | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Sb | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.13 | - | 0.12 |

| Se | 3.28 | 3.86 | 2.00 | 2.56 | 1 | 2 |

| Te | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.10 | - | 0.08 |

| Zn | 224.27 | 288.83 | 193 | 205.96 | 125 | 158 |

| Hg | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| As-Sb-S | 10.09 | 22.52 | 8.73 | 11.73 | 3.86 | 6.65 |

| As-Se-Hg | 3.30 | 3.89 | 2.17 | 2.86 | 1.02 | 2.01 |

| Ag-Pb | 14.65 | 16.36 | 12.90 | 13.94 | 8.41 | 10.67 |

| Fe-Cu-Mn | 2915.48 | 3450.12 | 2545.87 | 2750.55 | 1652.25 | 2122.60 |

| Au-Se | 3.28 | 3.88 | 2.11 | 2.75 | 1 | 2 |

| Au-Hg | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Au-Ag | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Au-Pb | 14.58 | 16.30 | - | 13.87 | 8.40 | 10.60 |

| Element/Assoc | Segment | α | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au | Background | −1.32 | −0.38 | 0.70 |

| Low Anomaly | −1.83 | −0.55 | 0.71 | |

| High Anomaly | −2.77 | −0.92 | 0.99 | |

| Ag | Background | −0.48 | −0.26 | 0.71 |

| Low Anomaly | −2.60 | −1.90 | 0.81 | |

| High Anomaly | −4.04 | −3.07 | 0.95 | |

| As | Background | −0.01 | −0.27 | 0.80 |

| Low Anomaly | +0.53 | −1.29 | 1.00 | |

| High Anomaly | +0.83 | −1.58 | 0.97 | |

| Ba | Background | +1.26 | −0.61 | 0.84 |

| Low Anomaly | +3.56 | −1.59 | 0.98 | |

| High Anomaly | +11.41 | −4.68 | 0.90 | |

| Cu | Background | +0.91 | −0.61 | 0.89 |

| Low Anomaly | +4.93 | −2.91 | 1.00 | |

| High Anomaly | +9.50 | −5.31 | 0.96 | |

| Fe | Background | +0.18 | −0.35 | 0.55 |

| Low Anomaly | +1.25 | −1.60 | 1.00 | |

| High Anomaly | +4.27 | −4.27 | 0.88 | |

| Mn | Background | +0.90 | −0.32 | 0.43 |

| Low Anomaly | +8.65 | −2.77 | 0.99 | |

| High Anomaly | +21.82 | −6.73 | 0.98 | |

| Pb | Background | +0.32 | −0.52 | 0.73 |

| Low Anomaly | +2.38 | −2.81 | 0.99 | |

| High Anomaly | +1.39 | −2.05 | 0.81 | |

| S | Background | −0.63 | −0.26 | 0.87 |

| Low Anomaly | −1.54 | −0.75 | 0.82 | |

| High Anomaly | −2.34 | −1.31 | 0.99 | |

| Sb | Background | −0.97 | −0.54 | 0.85 |

| Low Anomaly | — | — | — | |

| High Anomaly | −1.74 | −1.43 | 0.96 | |

| Se | Background | −0.19 | −0.39 | 0.56 |

| Low Anomaly | −0.26 | −0.52 | 0.74 | |

| High Anomaly | +0.39 | −3.40 | 0.81 | |

| Hg | Background | −0.82 | −0.35 | 0.41 |

| Low Anomaly | −1.20 | −0.48 | 0.49 | |

| High Anomaly | −3.97 | −2.01 | 0.87 | |

| As–Sb–S | Background | −0.01 | −0.28 | 0.81 |

| Low Anomaly | +0.56 | −1.31 | 1.00 | |

| High Anomaly | +0.85 | −1.58 | 0.97 | |

| As–Se–Hg | Background | −0.20 | −0.44 | 0.64 |

| Low Anomaly | −0.25 | −0.55 | 0.75 | |

| High Anomaly | +0.45 | −3.48 | 0.83 | |

| Ag–Pb | Background | +0.33 | −0.53 | 0.73 |

| Low Anomaly | +2.41 | −2.83 | 0.99 | |

| High Anomaly | +1.40 | −2.06 | 0.81 | |

| Fe–Cu–Mn | Background | +1.08 | −0.38 | 0.49 |

| Low Anomaly | +8.87 | −2.82 | 0.99 | |

| High Anomaly | +22.60 | −6.95 | 0.97 | |

| Au–Se | Background | −0.20 | −0.40 | 0.59 |

| Low Anomaly | −0.26 | −0.53 | 0.75 | |

| High Anomaly | +0.42 | −3.43 | 0.82 | |

| Au–Hg | Background | −1.00 | −0.45 | 0.70 |

| Low Anomaly | −3.31 | −1.77 | 0.82 | |

| High Anomaly | −3.16 | −2.37 | 0.96 | |

| Au–Ag | Background | −0.51 | −0.29 | 0.73 |

| Low Anomaly | −2.71 | −2.04 | 0.95 | |

| High Anomaly | −3.10 | −2.38 | 0.97 | |

| Au–Pb | Background | +0.32 | −0.52 | 0.73 |

| Low Anomaly | +2.38 | −2.81 | 0.99 | |

| High Anomaly | +1.39 | −2.05 | 0.81 |

| Mean + 2SD | Median + 2MAD | C-A Fractal Model | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Data | Log-Transformed Data | Raw Data | Log-Transformed Data | Low Anomaly | High Anomaly | |||||||

| Quantity | (%) | Quantity | (%) | Quantity | (%) | Quantity | (%) | Quantity | (%) | Quantity | (%) | |

| Au | 42 | 6.61 | 42 | 6.61 | 130 | 20.47 | 130 | 20.47 | 274 | 188 | 29.61 | |

| Ag | 20 | 3.15 | 20 | 3.15 | 79 | 12.44 | 53 | 8.35 | 190 | 29.92 | 206 | 32.44 |

| As | 34 | 5.35 | 27 | 4.25 | 140 | 22.05 | 100 | 15.75 | 193 | 30.39 | 191 | 30.08 |

| Ba | 23 | 3.62 | 7 | 1.10 | 80 | 12.60 | 30 | 4.72 | 175 | 27.56 | 196 | 30.87 |

| Cu | 28 | 4.41 | 13 | 2.05 | 89 | 14.02 | 53 | 8.35 | 194 | 30.55 | 189 | 29.76 |

| Fe | 36 | 5.67 | 24 | 3.78 | 123 | 19.37 | 71 | 11.18 | 192 | 30.24 | 190 | 29.92 |

| Mn | 20 | 3.15 | 3 | 0.47 | 66 | 10.39 | 40 | 6.30 | 191 | 30.08 | 192 | 30.24 |

| Pb | 18 | 2.83 | 14 | 2.20 | 72 | 11.34 | 48 | 7.56 | 188 | 29.61 | 194 | 30.55 |

| S | 49 | 7.72 | 49 | 7.72 | 175 | 27.56 | 175 | 27.56 | 135 | 21.26 | 175 | 27.56 |

| Sb | 37 | 5.83 | 32 | 5.04 | 173 | 27.24 | 173 | 27.24 | 0 | 0.00 | 198 | 31.18 |

| Se | 12 | 1.89 | 16 | 2.52 | 89 | 14.02 | 88 | 13.86 | 138 | 21.73 | 295 | 46.46 |

| Te | 36 | 5.67 | 36 | 5.67 | 123 | 19.37 | 123 | 19.37 | 0 | 0.00 | 199 | 31.34 |

| Zn | 26 | 4.09 | 15 | 2.36 | 89 | 14.02 | 70 | 11.02 | 186 | 29.29 | 196 | 30.87 |

| Hg | 21 | 3.31 | 21 | 3.31 | 25 | 3.94 | 25 | 3.94 | 447 | 70.39 | 140 | 22.05 |

| As-Sb-S | 35 | 5.51 | 27 | 4.25 | 147 | 23.15 | 96 | 15.12 | 191 | 30.08 | 191 | 30.08 |

| Au-Se-Hg | 12 | 1.89 | 17 | 2.68 | 92 | 14.49 | 88 | 13.86 | 192 | 30.24 | 200 | 31.50 |

| Ag-Pb | 18 | 2.83 | 14 | 2.20 | 72 | 11.34 | 48 | 7.56 | 191 | 30.08 | 191 | 30.08 |

| Fe-Cu-Mn | 22 | 3.46 | 3 | 0.47 | 68 | 10.71 | 45 | 7.09 | 192 | 30.24 | 190 | 29.92 |

| Au-Se | 11 | 1.73 | 16 | 2.52 | 92 | 14.49 | 88 | 13.86 | 189 | 29.76 | 206 | 32.44 |

| Au-Hg | 25 | 3.94 | 25 | 3.94 | 76 | 11.97 | 76 | 11.97 | 191 | 30.08 | 190 | 29.92 |

| Au-Ag | 22 | 3.46 | 23 | 3.62 | 86 | 13.54 | 86 | 13.54 | 212 | 33.39 | 191 | 30.08 |

| Au-Pb | 18 | 2.83 | 14 | 2.20 | 74 | 11.65 | 49 | 7.72 | 187 | 29.45 | 191 | 30.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Widodo, W.; Ernowo, E.; Pratama, R.N.; Noor, M.R.; Widhiyatna, D.; Putra, E.; Idrus, A.; Pardiarto, B.; Boakes, Z.; Parningotan, M.R.; et al. Integrating PCA and Fractal Modeling for Identifying Geochemical Anomalies in the Tropics: The Malang–Lumajang Volcanic Arc, Indonesia. Geosciences 2025, 15, 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120470

Widodo W, Ernowo E, Pratama RN, Noor MR, Widhiyatna D, Putra E, Idrus A, Pardiarto B, Boakes Z, Parningotan MR, et al. Integrating PCA and Fractal Modeling for Identifying Geochemical Anomalies in the Tropics: The Malang–Lumajang Volcanic Arc, Indonesia. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):470. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120470

Chicago/Turabian StyleWidodo, Wahyu, Ernowo Ernowo, Ridho Nanda Pratama, Mochamad Rifat Noor, Denni Widhiyatna, Edya Putra, Arifudin Idrus, Bambang Pardiarto, Zach Boakes, Martua Raja Parningotan, and et al. 2025. "Integrating PCA and Fractal Modeling for Identifying Geochemical Anomalies in the Tropics: The Malang–Lumajang Volcanic Arc, Indonesia" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120470

APA StyleWidodo, W., Ernowo, E., Pratama, R. N., Noor, M. R., Widhiyatna, D., Putra, E., Idrus, A., Pardiarto, B., Boakes, Z., Parningotan, M. R., Suseno, T., Damayanti, R., Sendjaja, P., Rachmawati, D., & Ramadani, A. H. P. (2025). Integrating PCA and Fractal Modeling for Identifying Geochemical Anomalies in the Tropics: The Malang–Lumajang Volcanic Arc, Indonesia. Geosciences, 15(12), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120470