Analyzing the Connectivity of Fracture Networks Using Natural Fracture Characteristics in the Khairi Murat Range, Potwar Region, Northern Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

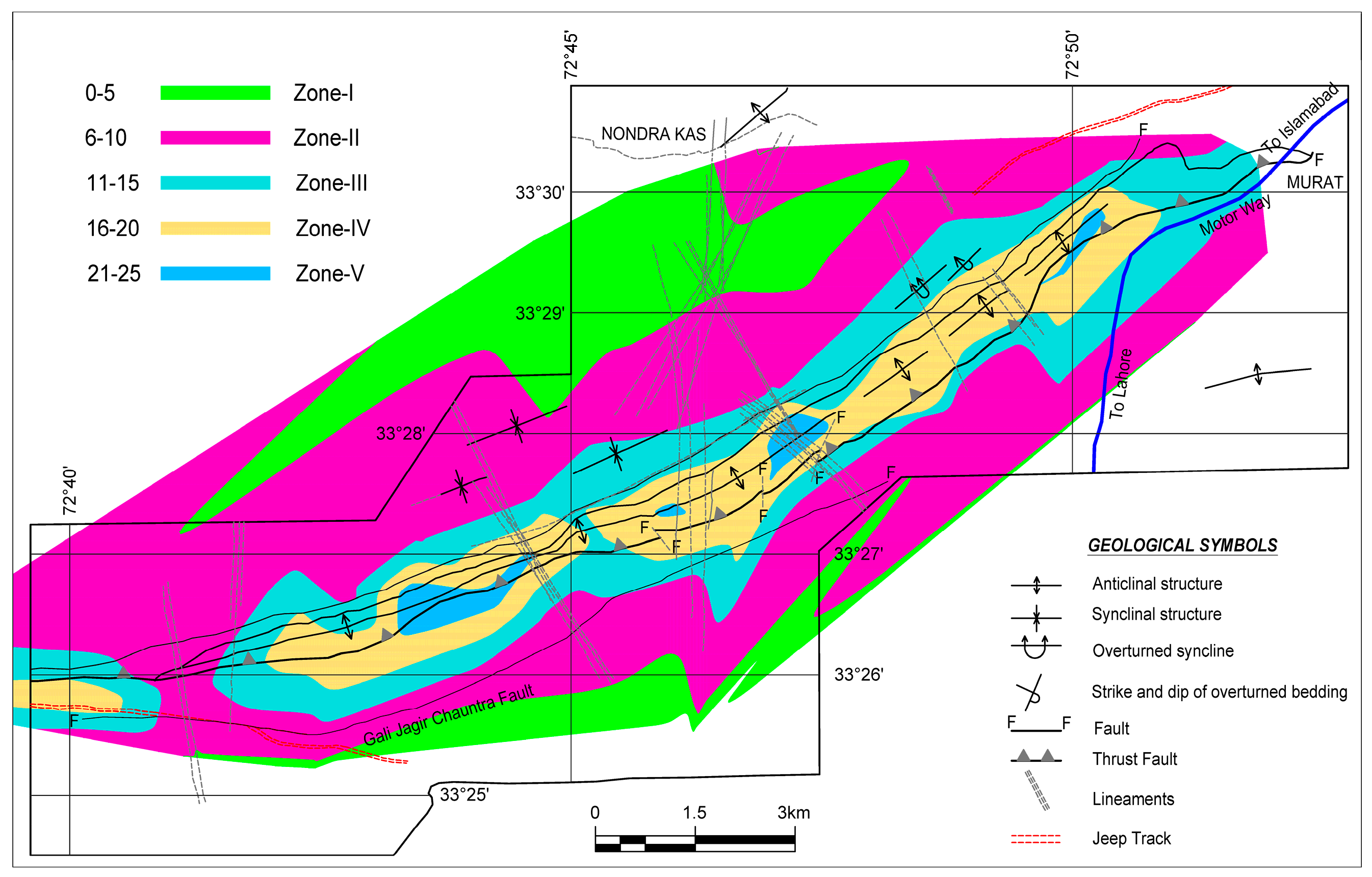

2. Geology and Structure

2.1. Geology of the Area

2.2. Structure of the Area

3. Data Acquisition Techniques and Analysis Methods

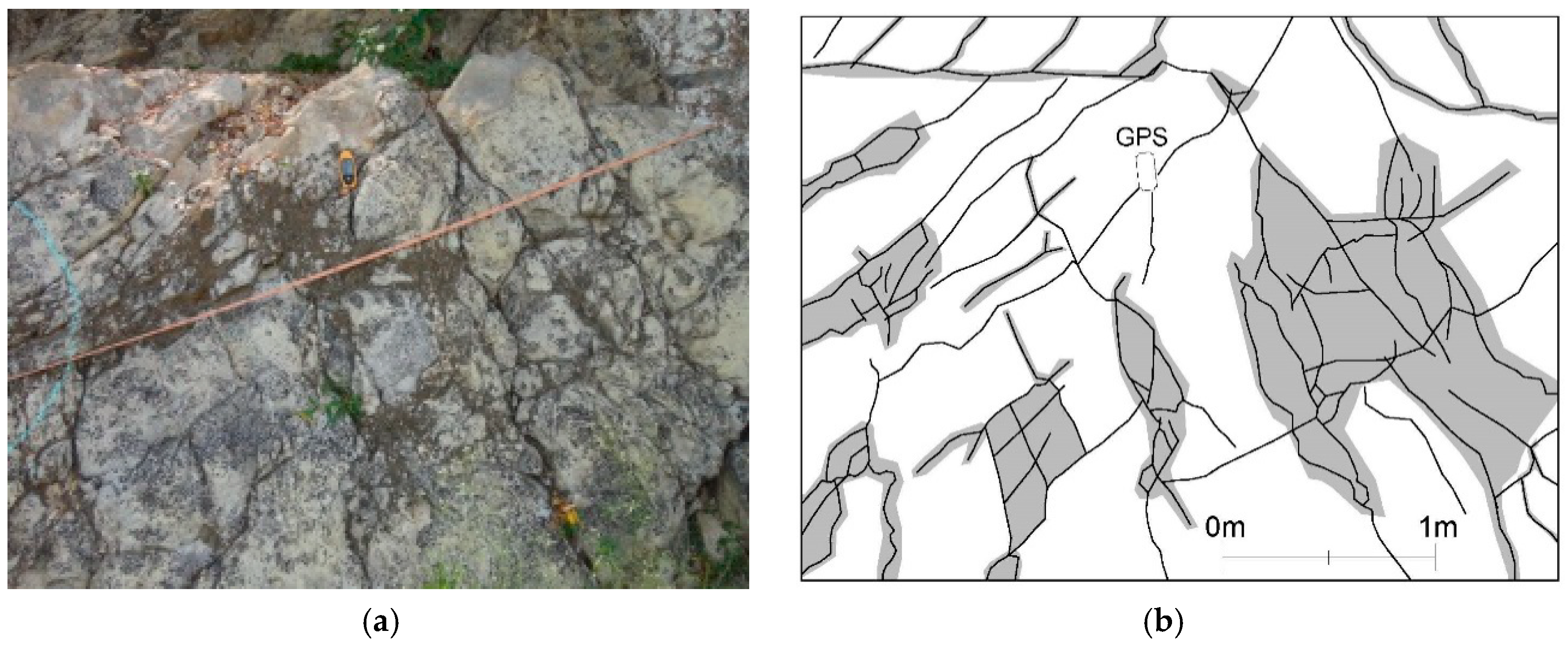

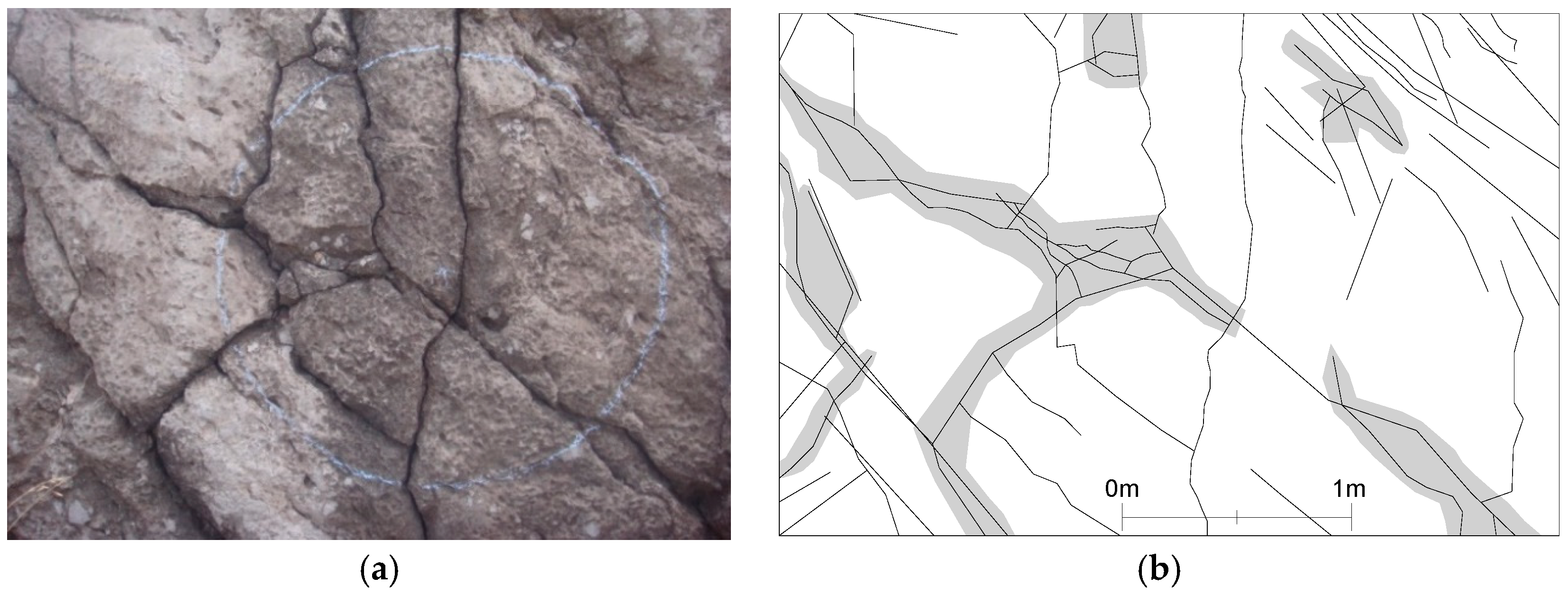

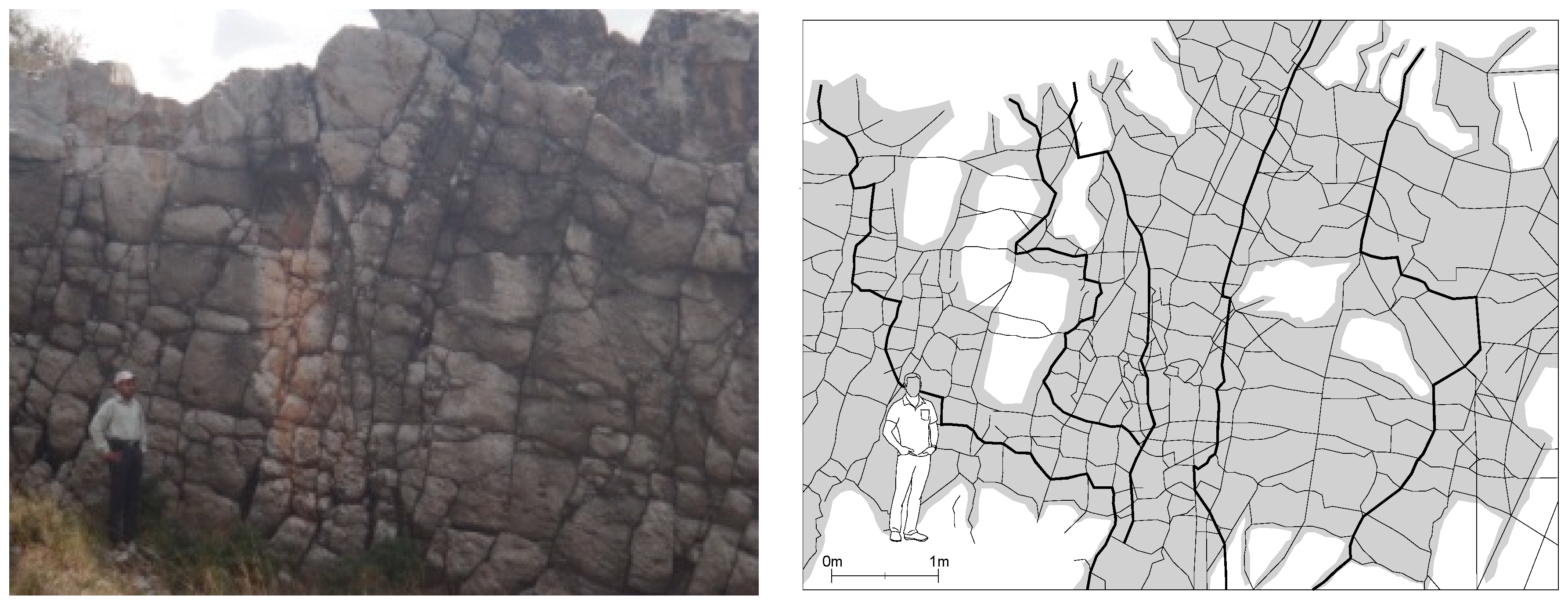

3.1. Data Collection from Outcrops

Circular Scanline Technique

3.2. Data Acquisition in the Lab

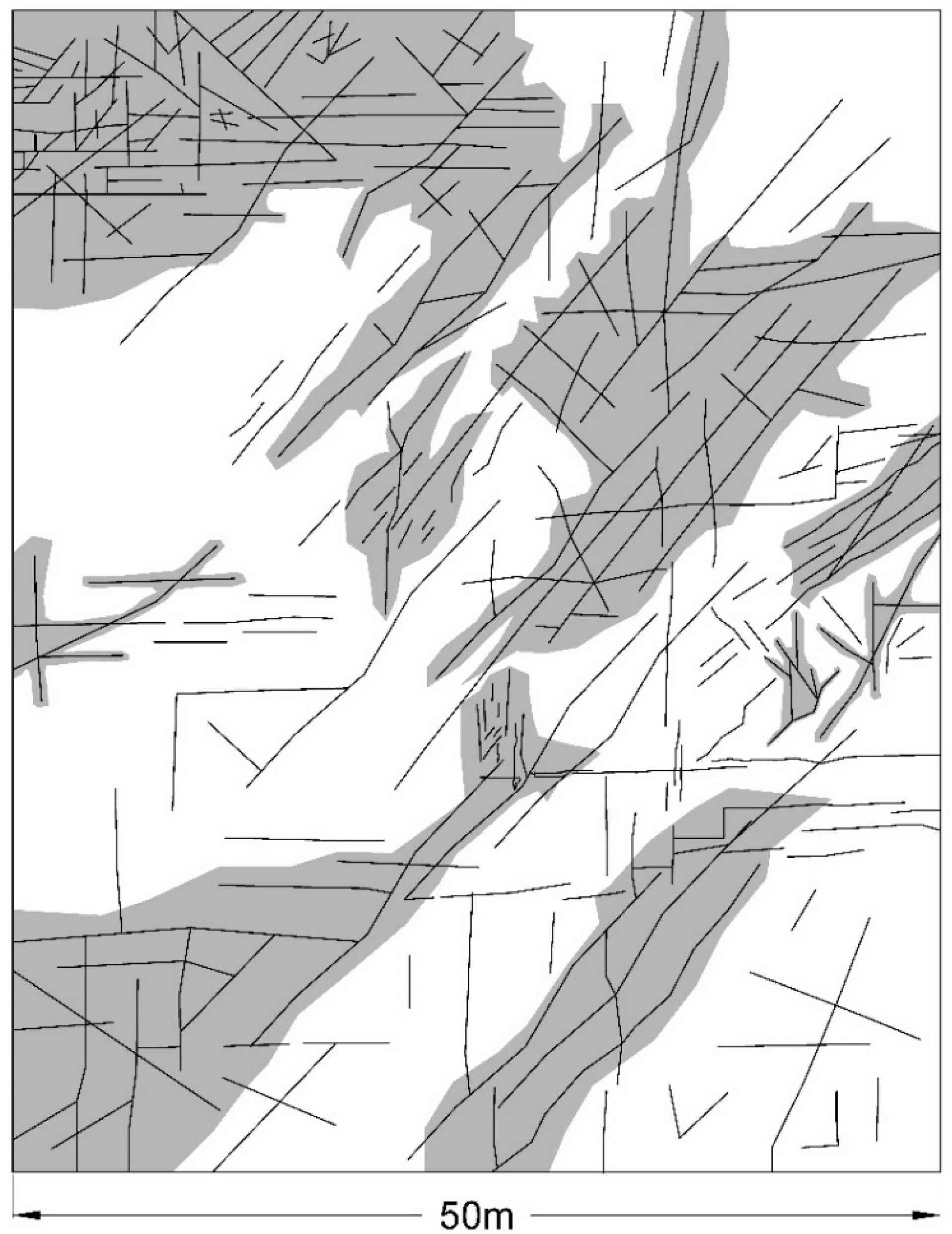

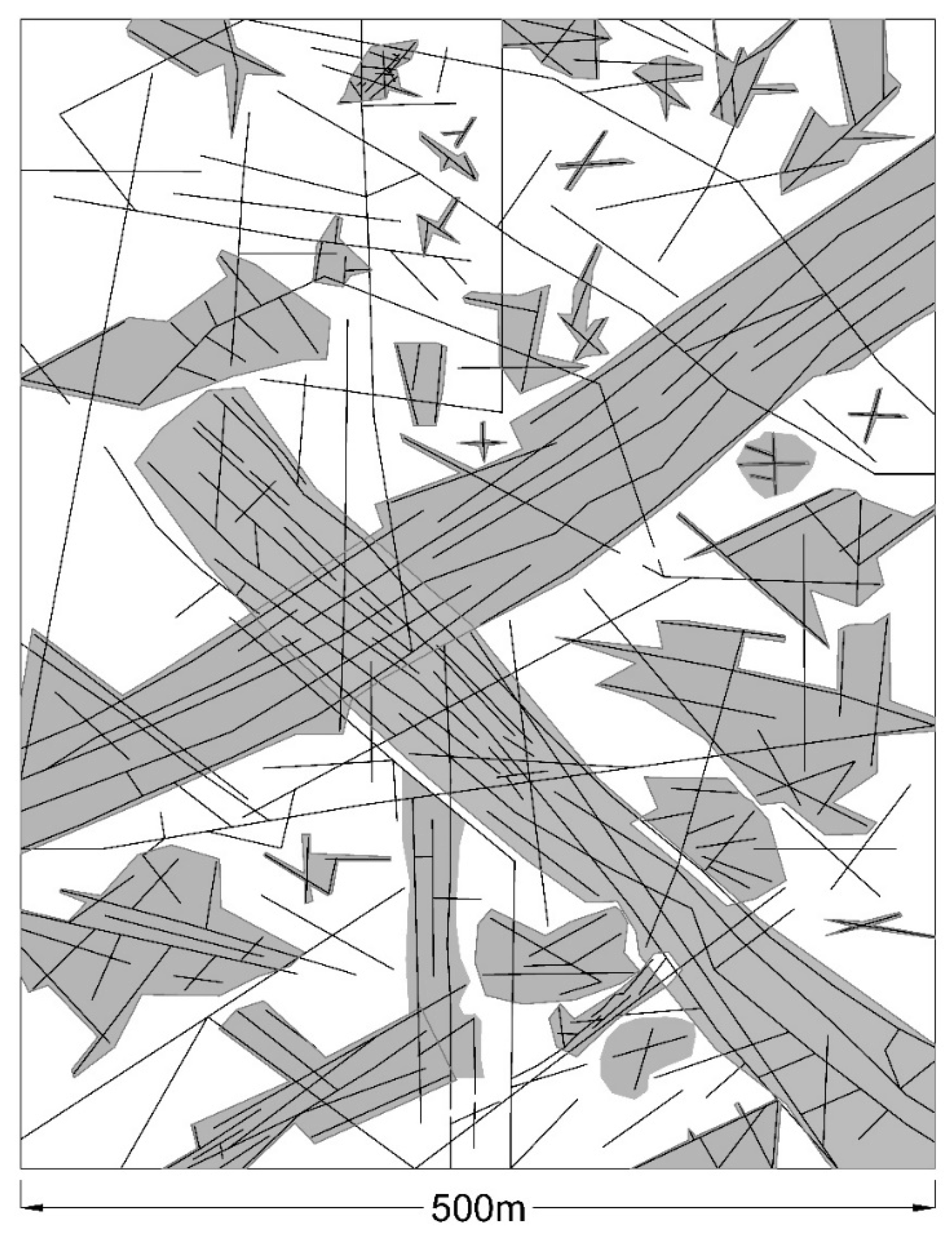

Photograph Trace Maps

4. Analysis Methods

4.1. Method Adopted from Davis et al. (1996) [76]

4.2. Method Adopted from Ghosh & Mitra (2009) [23]

5. Analysis and Results

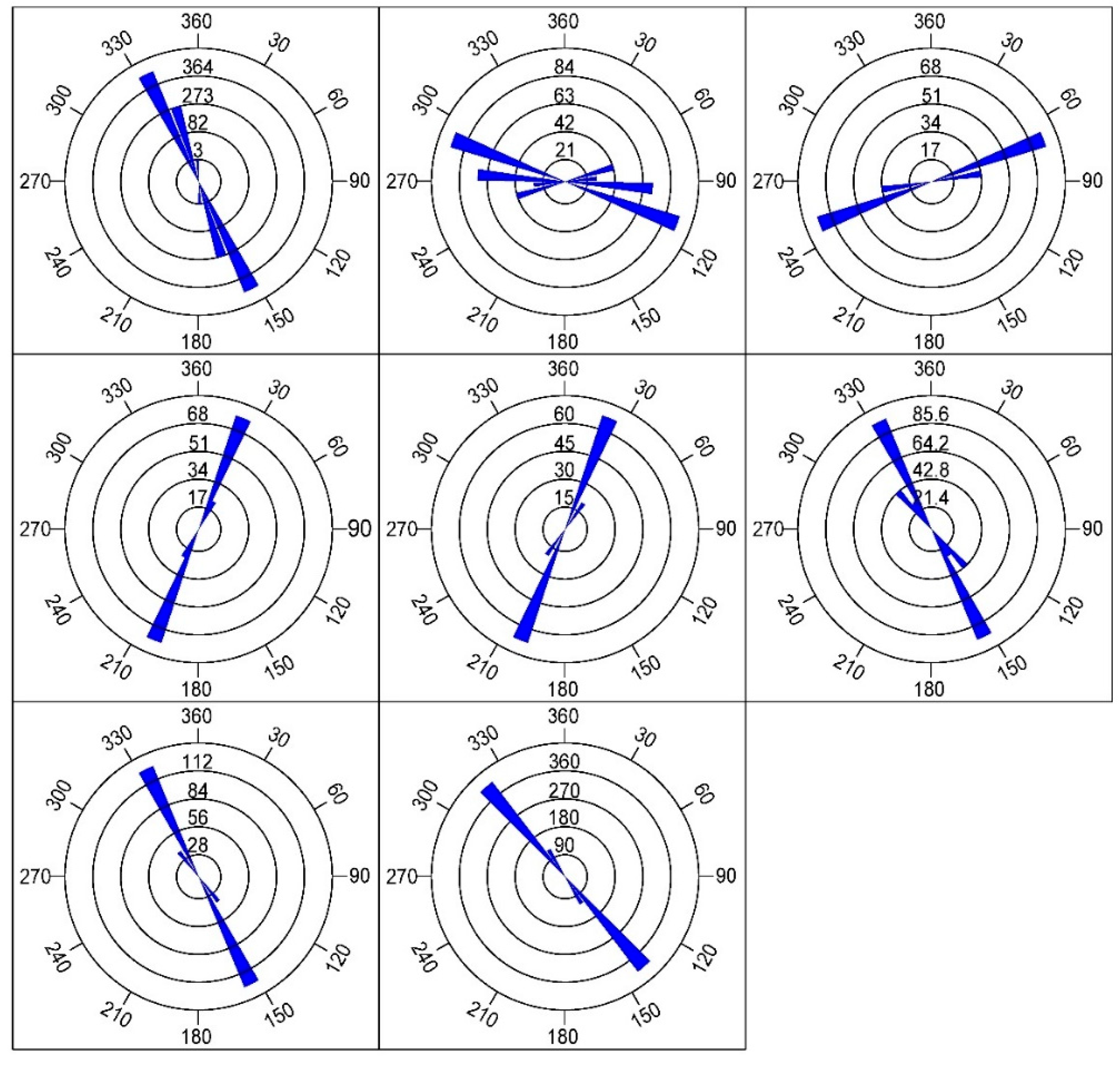

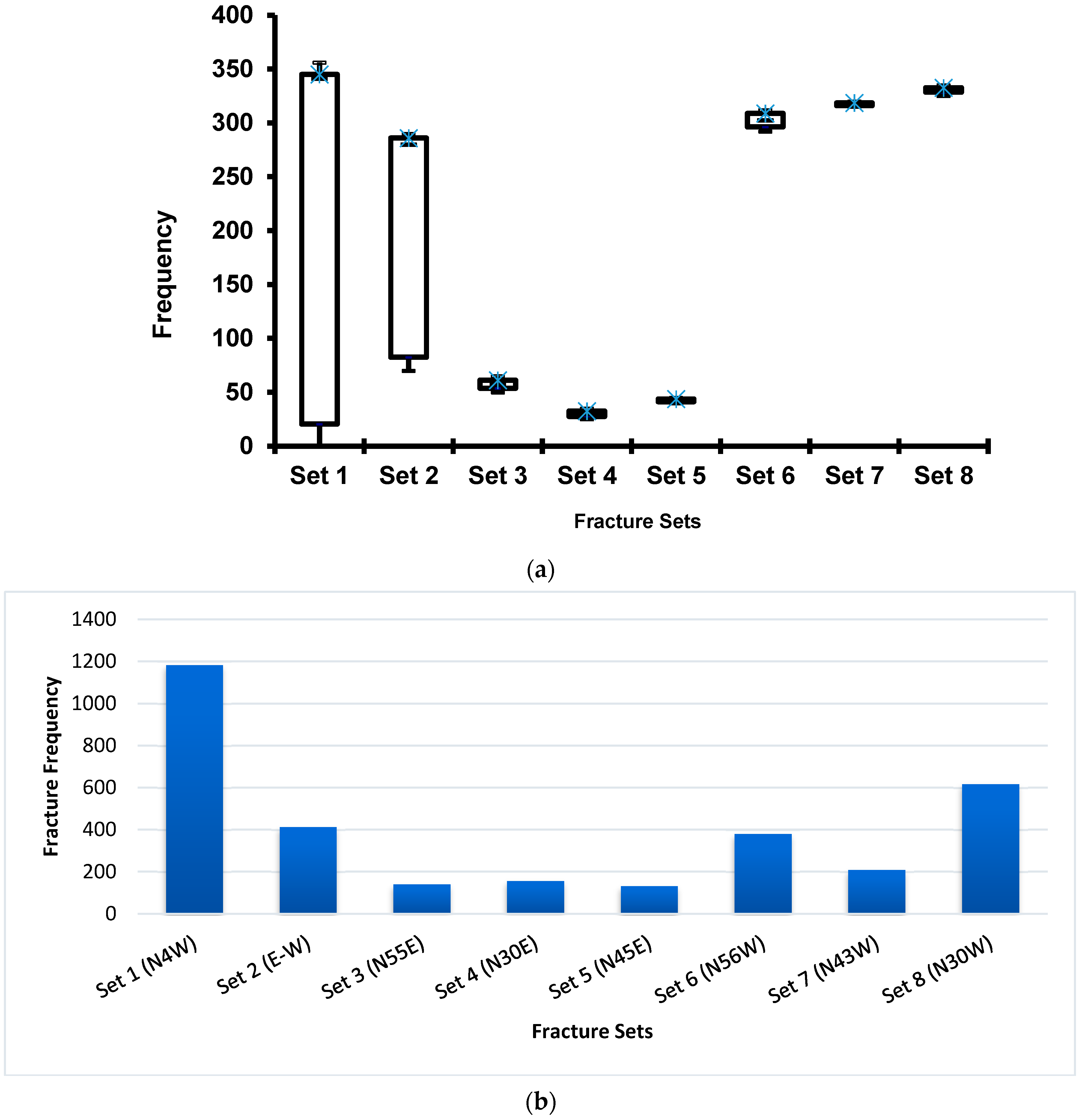

5.1. Fracture Orientation Analysis

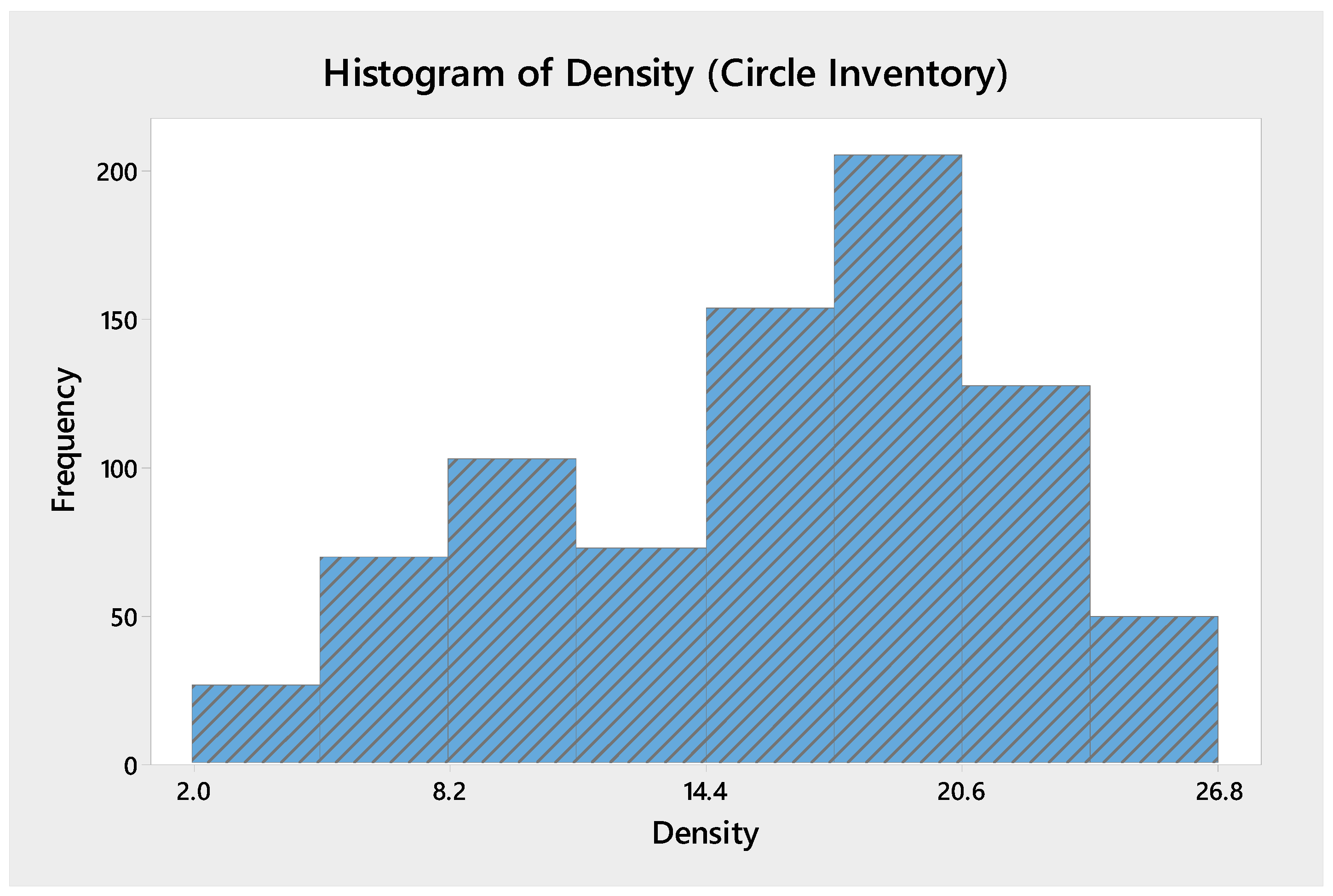

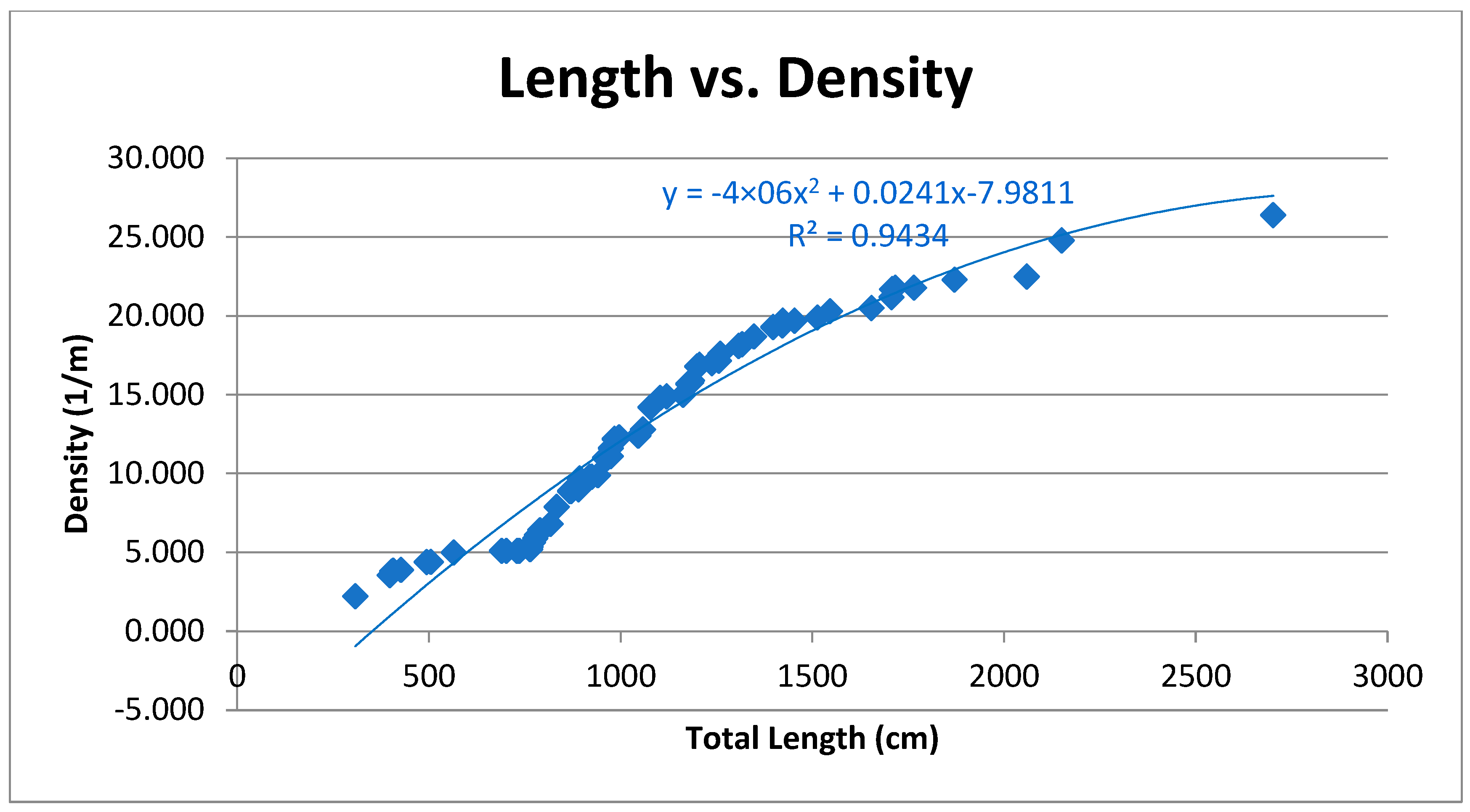

5.2. Fracture Density Analysis

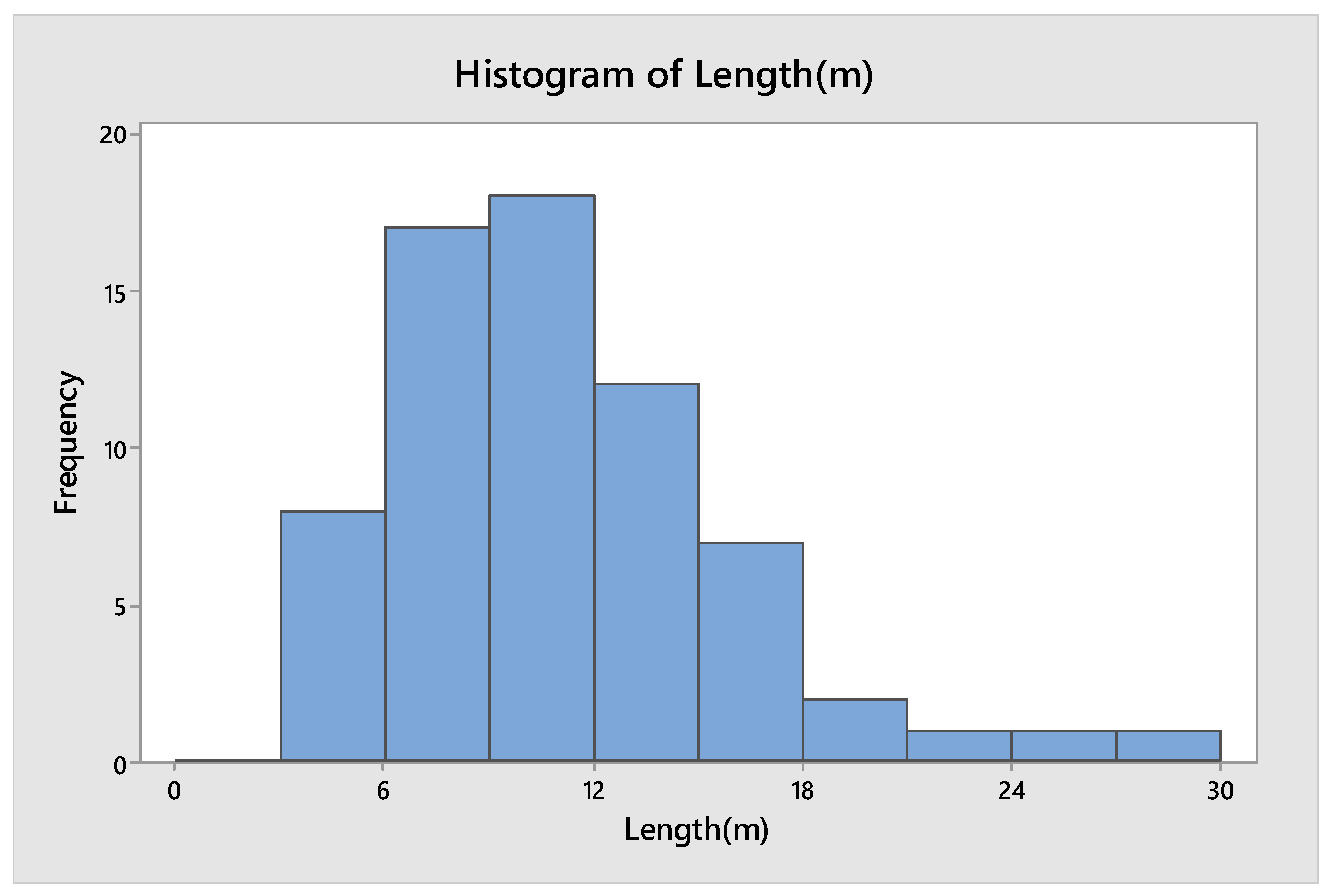

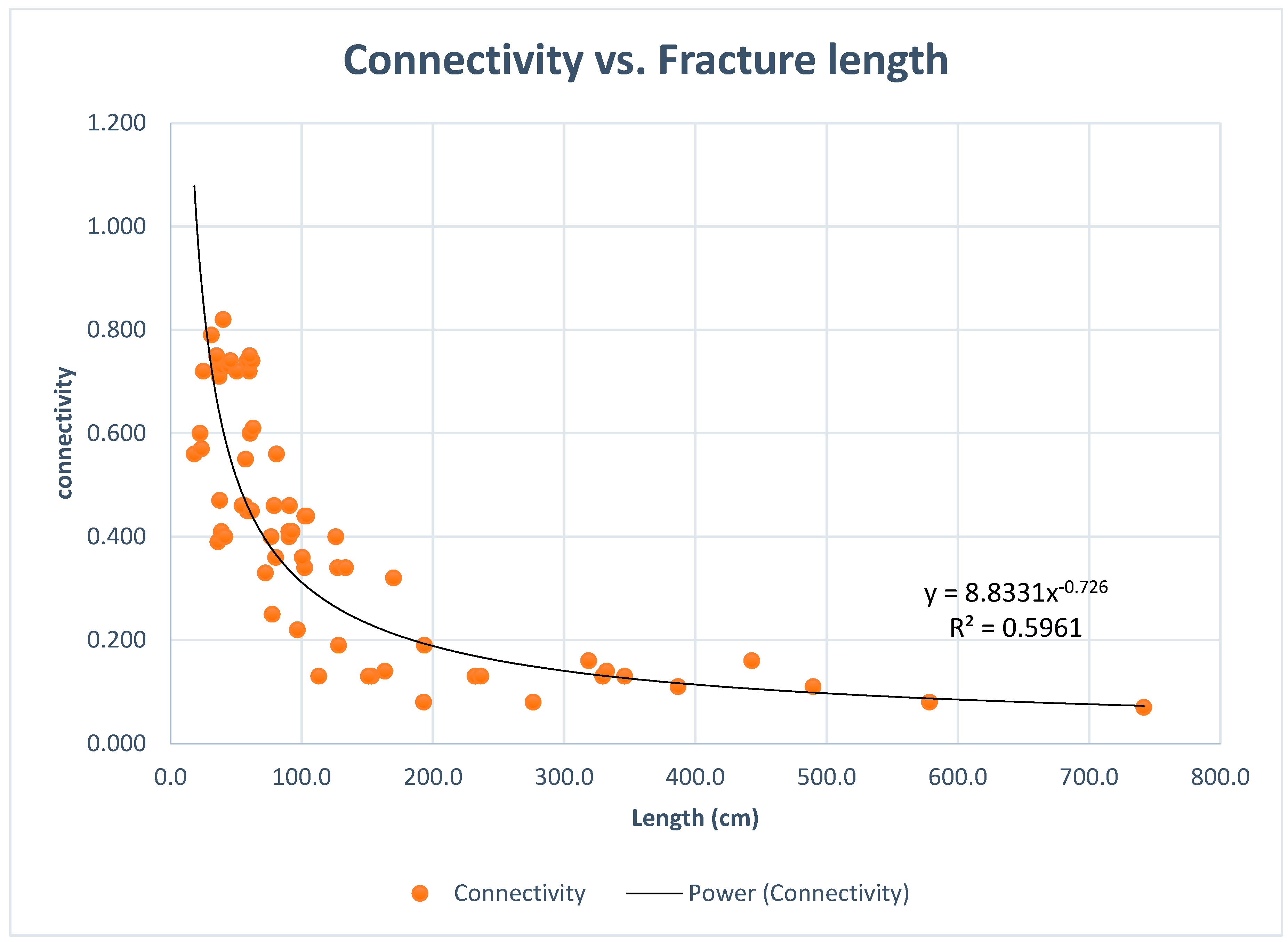

5.3. Fracture Length Analysis

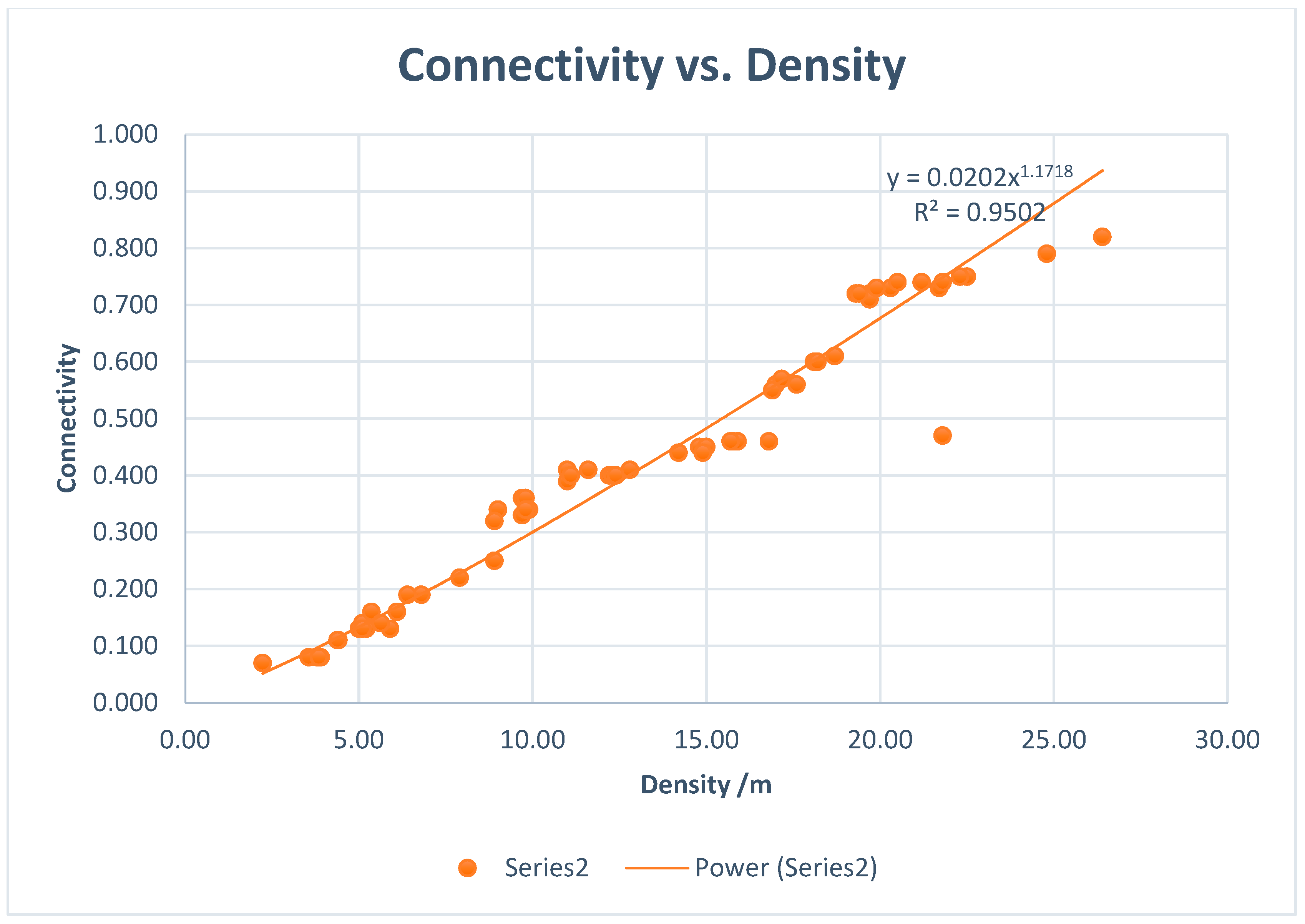

5.4. Connectivity and Cluster Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alghalandis, Y.F. ADFNE: Open-source software for discrete fracture network engineering, two- and three-dimensional applications. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 102, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.; Christiansson, R.; Hudson, J. Site Investigations: Strategy for Rock Mechanics Site Descriptive Model (No. SKB-TR-02-1); Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co.: Solna, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, E.; Martin, C.D. Fracture initiation and propagation in intact rock—A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 6, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.H.; Cao, P.; Lin, H.; Ma, G.W.; Zhang, C.Y.; Jiang, C. Failure characteristics of jointed rock-like material containing multi-joints under a compressive-shear test: Experimental and numerical analyses. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2018, 18, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Cao, R.H.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y. Damage and fracture behavior of rock. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8476537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjigeorgiou, J.; Grenon, M. Rock slope stability analysis using fracture systems. Int. J. Surf. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2005, 19, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, I.; Fredriksson, A.; Outters, N. Strategy for a Rock Mechanics Site Descriptive Model. Development and Testing of the Theoretical Approach (No. SKB-R-02-02); Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co.: Solna, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alfvén, L. Structural and Engineering Geological Investigation of Fracture Zones and Their Effect on Tunnel Construction. Master’s Thesis, Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Faoro, I.; Elsworth, D.; Candela, T. Evolution of the transport properties of fractures subject to thermally and mechanically activated mineral alteration and redistribution. Geofluids 2016, 16, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Fan, Q.; Huang, S.; Cheng, A. A one-dimensional line element model for transient free surface flow in porous media. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 392, 125747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follin, S.; Stigsson, M.; Leven, J. Discrete fracture network characterization and modeling in the Swedish program for nuclear waste disposal in crystalline rocks using information acquired by difference flow logging and borehole wall image logging. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts; Moscone Center West, 800 Howard Street: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karvounis, D.; Jenny, P. Modeling of flow and transport in enhanced geothermal systems. In Proceedings of the 36th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 31 January–2 February 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, D.M.; Rishi, P.; Yong, Z. Hydrogeologic characterization of fractured rock masses intended for disposal of radioactive waste. In Radioactive Waste; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alghalandis, Y.F.; Xu, C.; Dowd, P.A. Connectivity index and connectivity field towards fluid flow in fracture-based geothermal reservoirs. Worksh. Geotherm. Reserv. Eng. 2013, 38, 417–427. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Chang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Oostrom, M.; Kneafsey, T.J.; Mehta, H. Pore-scale supercritical CO2 dissolution and mass transfer under drainage conditions. Adv. Water Resour. 2017, 100, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dverstorp, B. Analyzing flow and transport in fractured rock using the discrete fracture network concept. In Hydraulic Engineering; Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.B.; Lee, C.C.; Lee, C.H.; Yeh, H.F.; Lin, H.I. Application of fracture network model with crack permeability tensor on flow and transport in fractured rock. Eng. Geol. 2010, 116, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejam, M. Derivation of dispersion coefficient in an electro-osmotic flow of a viscoelastic fluid through a porous-walled microchannel. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 204, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.-B. A numerical procedure for modeling the seepage field of water-sealed underground oil and gas storage caverns. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 66, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, B. Characterizing flow and transport in fractured geological media: A review. Adv. Water Resour. 2002, 25, 861–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Li, B.; Jiang, Y.; Jing, L. Numerical modelling of fluid flow tests in a rock fracture with a special algorithm for contact areas. Comput. Geotech. 2009, 36, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, T.; Prasad, R.; Chakrabarti, S. Evaluation of regional fracture properties for groundwater development using hydro-litho-structural domain approach in variably fractured hard rocks of Purulia district, West Bengal, India. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 123, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K.; Mitra, S. Structural controls of fracture orientations, intensity, and connectivity, Teton anticline, Sawtooth Range, Montana. AAPG Bull. 2009, 93, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, D.; Bianchi, M. Preliminary results from the use of entrograms to describe transport in fractured media. Acque Sotter.—Ital. J. Groundw. 2019, 8, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, J.; Sheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Fan, Q.; Qin, H. Evaluation of connectivity characteristics on the permeability of two-dimensional fracture networks using geological entropy. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Pollard, D.D. Imaging 3-D fracture networks around boreholes. AAPG Bull. 2002, 86, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckenby, R.J.; Sanderson, D.J.; Lonergan, L. Estimating flow heterogeneity in natural fracture systems. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2005, 148, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, D.J.; Nixon, C.W. Topology, connectivity and percolation in fracture networks. J. Struct. Geol. 2018, 115, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadgu, T.; Karra, S.; Kalinina, E.; Makedonska, N.; Hyman, J.D.; Klise, K.; Wang, Y. A comparative study of discrete fracture network and equivalent continuum models for simulating flow and transport in the far field of a hypothetical nuclear waste repository in crystalline host rock. J. Hydrol. 2017, 553, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somr, M.; Nezerka, V.; Kabele, P.; Svagera, O. Review of Discrete Fracture Network Modeling; Technical Report 74/2016/ENG; Joint Venture of Czech Technical University in Prague and Czech Geological Survey: Dejvice, Czech Republic, 2016; pp. 30–35. Available online: https://inis.iaea.org/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/51/100/51100979.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Sanderson, D.J. (Eds.) Numerical Modelling and Analysis of Fluid Flow and Deformation of Fractured Rock masses; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.C.; Lee, C.H.; Yeh, H.F.; Lin, H.I. Modeling spatial fracture intensity as a control on flow in fractured rock. Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 63, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Nagel, N.; Lee, B.; Sanchez-Nagel, M. Fracture Network Connectivity—A Key to Hydraulic Fracturing Effectiveness and Microseismicity Generation. In ISRM International Conference for Effective and Sustainable Hydraulic Fracturing, Brisbane, Australia, Paper Number: ISRM-ICHF-2013-053; InTech: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Lu, X.; Shen, W.; Hu, X. Study on the effects of fracture on permeability with pore-fracture network model. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2018, 36, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Dowd, P.A.; Mardia, K.V.; Fowell, R.J. A connectivity index for discrete fracture networks. Math. Geol. 2006, 38, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausse, J.; Dezayes, C.; Genter, A.; Bisset, A. Characterization of fracture connectivity and fluid flow pathways derived from geological interpretation and 3D modelling of the deep seated EGS reservoir of Soultz (France). In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford, CA, USA, 28–30 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Molebatsi, T.; Torres, S.G.; Li, L.; Bringemeier, D.; Wang, X. Effect of fracture permeability on connectivity of fracture networks. In Proceedings of the International Mine Water Conference, Pretoria, South Africa, 19–23 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, D.; Feng, G.; Chi, M. Modelling method of heterogeneous rock mass and DEM investigation of seepage characteristics. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Dowd, P. A new computer code for discrete fracture network modelling. Comput. Geosci. 2010, 36, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, H.O.; Nasseri, M.H.B.; Young, R.P. Fluid flow complexity in fracture networks: Analysis with graph theory and LBM. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1107.4918. [Google Scholar]

- Alghalandis, Y.F. Stochastic Modelling of Fractures in Rock Masses. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goc, R.; Darcel, C.; Davy, P.; Pierce, M.; Brossault, M.A. Effective elastic properties of 3D fractured systems. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Discrete Fracture Network Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 19–22 October 2014; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, J.D.; Karra, S.; Makedonska, N.; Gable, C.W.; Painter, S.L.; Viswanathan, H.S. dfn Works: A discrete fracture network framework for modeling subsurface flow and transport. Comput. Geosci. 2015, 84, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillot, J.; Davy, P.; Le Goc, R.; Darcel, C.; De Dreuzy, J.R. Connectivity, permeability, and channeling in randomly distributed and kinematically defined discrete fracture network models. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 8526–8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoine, E.; Davy, P.; Darcel, C.; Munier, R. A Discrete Fracture Network Model with Stress-Driven Nucleation: Impact on Clustering, Connectivity, and Topology. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, B.; Nixon, C.W.; Sanderson, D.J. NetworkGT: A GIS tool for geometric and topological analyses of two-dimensional fracture networks. Geosphere 2018, 14, 1618–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, A.H.; Jan, M.Q. Geology and Tectonics of Pakistan; Graphic Publishers: Earth City, MO, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kazmi, A.H.; Abbasi, I.A. Stratigraphy & Historical Geology of Pakistan; Department & National Centre of Excellence in Geology: Peshawar, Pakistan, 2008; p. 524. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, H.; Hussain, J.; Tariq, M.; Ehsan, M.; Khurshid, S.; Khan, S.; Anwar, W. Sedimentological and diagenetic analysis of Early Eocene Margalla Hill Limestone, Shahdara area, Islamabad, Pakistan: Implications for reservoir potential. Carbonates Evaporites 2022, 37, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Siddiqui, M.I.; Munir, M.H. Micropalaeontology and Depositional Environment of the Early Eocene Margalla Hill limestone and Chorgali formation of the Khairi Murat Range, Potwar Basin, Pakistan. Pak. J. Hydrocarb. Res. 2006, 16, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba, M. Depositional and Diagenetic Environment of Carbonates of Chorgali Formation, Salt Range-Potwar Plateau, Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan, 2001; p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- Benchilla, L.; Rudy, S.; Khursheed, A.; François, R. Sedimentology and diagenesis of the Chorgali Formation in the Potwar Plateau and Salt Range, Himalayan foothills (N-Pakistan). Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Search Discov. Artic. 2002, 11, 900. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgan, H.; Abbas, G. On the Chorgali Formation at the Type Locality. Pak. J. Hydrocarb. Res. 1991, 3, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.Z.; Rahman, Z.U.; Khattak, Z.; Ishfaque, M. Microfacies and diagenetic analysis of Chorgali Carbonates, Chorgali Pass, Khair-E-Murat range: Implications for hydrocarbon reservoir characterization. Pak. J. Geol. 2017, 1, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Hanif, M.; Jan, I.U.; Ishaq, M.; Khan, M.Y. Eocene carbonate microfacies distribution of the Chorgali Formation, Galijagir, Khair-e-Murat Range, Potwar Plateau, Pakistan: Approach of reservoir potential using outcrop analogue. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I. Stratigraphy of Pakistan; Memoirs Volume 12; Geological Survey of Pakistan: Quetta, Pakistan, 1977.

- Ali, A.; Farid, A.; Awan, U.F.; Amin, Y.; Zafar, W.A.; Bangash, A.A.; Ullah, S. Gravity survey to delineate the extension of the Khair-i-Murat Thrust under the sub-Himalayas, Kohat-Potwar region, Pakistan. Himal. Geol. 2023, 44, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jadoon, I.A.K.; Frisch, W.; Jaswal, T.M.; Kemal, A. Triangle zone in the Himalayan foreland, north Pakistan. In Himalaya and Tibet: Mountain Roots to Mountain Tops; Macfarlane, A., Sorkhabi, R.B., Quade, J., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1999; Special Paper 328. [Google Scholar]

- Geological Survey of Pakistan. Geological Map of Khairi Murat Range, District Attock, Scale 1: 50,000; Map Series No.47; Geological Survey of Pakistan: Quetta, Pakistan, 2001.

- Jaswal, T.M.; Lillie, R.J.; Lawrence, R.D. Structure and evolution of the northern Potwar deformed zone, Pakistan. AAPG Bull. 1997, 81, 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoon, I.A.K.; Frisch, W. Hinterland-divergent tectonic wedge below Riwat thrust, Himalayan foreland, Pakistan: Implications for Hydrocarbon Exploration. AAPG Bull. 1997, 81, 438–448. [Google Scholar]

- Jadoon, I.A.K.; Frisch, W.; Kemal, A.; Jaswal, T.M. Thrust geometries and kinematics in the Himalayan foreland (North Potwar deformed zone), North Pakistan. Geol. Rundsch. 1997, 86, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jadoon, I.A.K.; Frisch, W.; Jadoon, M.S.K. Structural Traps and Hydrocarbon Exploration in the Salt Range/Potwar Plateau, North Pakistan. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference, Islamabad, Pakistan, 7–8 May 2008; pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jadoon, I.A.K.; Hinderer, M.; Wazir, B.; Yousaf, R.; Bahadar, S.; Hassan, M.; Jadoon, S. Structural styles, hydrocarbon prospects, and potential in the Salt Range and Potwar Plateau, north Pakistan. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 5111–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghal, M.A.; Saqi, M.I.; Hameed, A.; Bugti, M.N. Subsurface geometry of Potwar sub-basin in relation to structuration and entrapment. Pak. J. Hydrocarb. Res. 2007, 17, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Bannert, D. Structural Observation of the Margalla Hills, Pakistan and the Nature of the Main Boundary Thrust. Pak. J. Hydrocarb. Res. 1998, 10, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.K.; Khan, J.; Mughal, M.S.; Lashari, M.R.; Sahito, A.G.; Hameed, F.; Razzaq, S.S. Petrotectonic framework of Siwalik Group in Khairi Murat-Kauliar area, Potwar Sub-Basin, Pakistan. Kuwait J. Sci. 2023, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, S.M.; Siddiqi, M.I. Structural Geology and Hydrocarbon prospects of Khairi Murat Area, Potwar Sub-basin, Pakistan. Pak. J. Hydrocarb. Res. 2011, 21, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.M.; Robert, J.L.; Robert, S.Y.; Gary, D.J.; Yousuf, M.; Zamin, H.A.S. Development of the Himalayan frontal thrust zone: Salt Range, Pakistan. Geology 1988, 16, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennock, E.S.; Lillie, R.J.; Zaman, A.S.H.; Yousaf, M. Structural interpretation of seismic reflection data from eastern Salt Range and Potwar Plateau, Pakistan. AAPG Bull. 1989, 73, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wandrey, C.J.; Law, B.E.; Shah, H.A. Patala-Nammal Composite Total Petroleum System, Kohat-Potwar Geologic Province, Pakistan; Version 1.0., US Geological Survey Bulletin 2208-B; US Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/b2208-b/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).[Green Version]

- Baecher, G.B. Progressively censored sampling of rock joint traces. J. Int. Assoc. Math. Geol. 1980, 12, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauldon, M. Estimating mean fracture trace length and density from observations in convex windows. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 1998, 31, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauldon, M.; Dunne, W.M.; Rohrbaugh, M.B. Circular scanlines and circular windows: New tools for characterising the geometry of fracture traces. J. Struct. Geol. 2001, 23, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbaugh Jr, M.B.; Dunne, W.M.; Mauldon, M. Estimating fracture trace intensity, density, and mean length using circular scan lines and windows. AAPG Bull. 2002, 86, 2089–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.H.; Reynolds, S.J.; Cruden, A.R. Structural geology of rocks and regions. Econ. Geol. Bull. Soc. Econ. Geol. 1996, 91, 1163. [Google Scholar]

- Mauldon, M.; Rohrbaugh, M.B.; Dunne, W.M.; Lawdermilk, W. Fracture intensity estimates using circular scanlines. In Proceedings of the 37th U.S. Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS), Paper Number: ARMA-99-0777, Vail, CO, USA, 6–9 June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeb, C.; Gomez-Rivas, E.; Bons, P.D.; Blum, P. Evaluation of sampling methods for fracture network characterization using outcrops. AAPG Bull. 2013, 97, 1545–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, A.; Shahriar, K.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Aalianvari, A.; Esmaeilzadeh, A. Effect of shape and size of sampling window on the deamination of average length, intensity and density of trace discontinuity. In Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering: From Past to the Future; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-03265-1. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, D.C.P.; Harris, S.D.; Mauldon, M. Use of curved scanlines and boreholes to predict fracture frequencies. J. Struct. Geol. 2003, 25, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dershowitz, W.S.; Herda, H.H. Interpretation of fracture spacing and intensity. In Proceedings of the 33rd US Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS), Santa Fe, NM, USA, 3–5 June 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Daemen, J.J. Fractal characteristics of rock discontinuities. Eng. Geol. 1993, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.E.; Shi, G. Block Theory and its Applications to Rock Engineering; Prentice-Hall International: London, UK, 1985; 338p. [Google Scholar]

- Florez-Niño, J.-M.; Aydin, A.; Mavko, G.; Antonellini, M.; Ayaviri, A. Fault and fracture systems in a fold and thrust belt: An example from Bolivia. AAPG Bull. 2005, 89, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Khirevich, S.; Patzek, T.W. Impact of fracture geometry and topology on the connectivity and flow properties of stochastic fracture networks. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR028652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, S.D. Fluid Flow in Discontinuities in Discontinuities Analysis in Rock Engineering; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1993; pp. 340–381. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y. Rock fracture skeleton tracing by image processing and quantitative analysis by geometry features. J. Geophys. Eng. 2016, 13, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, D. Introduction to Percolation Theory; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1985; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, B.; Balberg, I. Percolation theory and its application to groundwater hydrology. Water Resour. Res. 1993, 29, 775–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, B. Analysis of fracture network connectivity using percolation theory. Math. Geol. 1995, 27, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odling, N.E. Network properties of a two-dimensional natural fracture pattern. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1992, 138, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odling, N.E. The development of network properties in natural fracture patterns: An example from the Devonian sandstones of western Norway. In Fractured and Jointed Rock Masses, Proceedings of the Conference on Fractured and Jointed Rock Masses, Lake Tahoe, CA, USA, 3–5 June 1992; Hardcover–Import; Cook, N.G.W., Goodman, R.E., Myer, L.R., Tsang, C.-F., Eds.; A.A. Balkema, Brookfield: Brookfield, VT, USA, 1996; pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Odling, N.E. Scaling and connectivity of joint systems in sandstones from western Norway. J. Struct. Geol. 1997, 19, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, S.; Arbues, P.; Snidero, M.; Carrera, N.; Muñoz, J.A. Open Plot Project: An open-source toolkit for 3-D structural data analysis. Solid Earth 2011, 2, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, P.L.; Al-Kahdi, A.; Barka, A.A.; Bevan, T.G. Aspects of analyzing brittle structural structures. Ann. Tecton. 1987, 1, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mardla, K. Statistics of Directional Data; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Michelena, R.J.; Godbey, K.S.; Wang, H.; Gilman, J.R.; Zahm, C.K. Estimation of dispersion in orientations of natural fractures from seismic data: Application to DFN modeling and flow simulation. Lead. Edge 2013, 32, 1502–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangerl, C.; Koppensteiner, M.; Strauhal, T. Semiautomated Statistical Discontinuity Analyses from Scanline Data of Fractured Rock Masses. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkaya, S.I. A Simple Formula to Estimate 2D Fracture Connectivity. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2011, 14, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Wu, C.; Wu, Z.; Xue, Z. Joint development and tectonic stress field evolution in the southeastern Mesozoic Ordos Basin, west part of North China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2016, 127, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasti, N.; Akram, S.; Ahmad, I.; Usman, M. Rock fractures characterization in Khairi Murat Range, Sub Himalayan fold and thrust belt, North Pakistan. Nucleus 2018, 55, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodner, M.W.; Clarke, S.M.; Burley, S.D.; Leslie, A.G.; Haslam, R. Combining topology and fractal dimension of fracture networks to characterize structural domains in thrusted limestones. J. Struct. Geol. 2021, 153, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, C.E. Fracture spatial density and the anisotropic connectivity of fracture networks. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 2000, 122, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

| Age | Group | Formation | Lithology | Lithological Description | Tectonic Setting | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era | Period | Epoch | ||||||

| Cenozoic | Tertiary | Pleisto- cene | Siwaliks | Lei Conglomerate |  | Conglomerate | Molasses | |

| Soan |  | Siltstone, Sandstone & rare conglomerate | ||||||

| Pliocene | Dhok Pathan |  | Claystone, Siltstone & minor sandstone | |||||

| Nagri |  | Claystone & Sandstone | ||||||

| Miocene | Chinji |  | Claystone & Sandstone | |||||

| Rawalpindi | Kamlial |  | Claystone & Sandstone | |||||

| Murree |  | Sandstone, Claystone & Conglomerate | ||||||

| Oligocene | Unconformity | Platform | ||||||

| Eocene | Cherat | Kohat (Not Exposed) |  | Limestone | ||||

| Kuldana |  | Shale | ||||||

| Chor Gali |  | Limestone, Dolomite & Shale | ||||||

| Margalla Hill | Sakesar |  | Limestone | |||||

| Nammal |  | Shale, Limestone | ||||||

| Fracture Set No. | Mean Orientation | Mean Strike | Mean Dip | Dip Magnitude | Dip Direction | Fracture Frequency | Dispersion Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 355 | N4W | 87 | 90 | Vertical | 1182 | 0.97 |

| 2 | 283 | E-W | 89 | 90 | Vertical | 412 | 0.26 |

| 3 | 058 | N55E | 50SE | 50 | SE | 139 | 1.00 |

| 4 | 030 | N30E | 90 | 90 | Vertical | 156 | 1.00 |

| 5 | 043 | N45E | 49NW | 50 | NW | 131 | 1.00 |

| 6 | 302 | N56W | 44NE | 45 | NE | 380 | 0.99 |

| 7 | 317 | N43W | 90 | 90 | Vertical | 208 | 1.00 |

| 8 | 330 | N30W | 88 | 90 | Vertical | 616 | 1.00 |

| Zone I | Zone II | Zone III | Zone IV | Zone V | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 4.63 | Mean | 8.57 | Mean | 13.38 | Mean | 18.62 | Mean | 22.81 |

| Median | 5.10 | Median | 8.95 | Median | 12.80 | Median | 18.70 | Median | 22.05 |

| St. Dev. | 0.92 | St. Dev. | 1.42 | St. Dev | 1.86 | St. Dev. | 1.31 | St. Dev | 1.82 |

| Kurtosis | 1.40 | Kurtosis | −0.89 | Kurtosis | −1.73 | Kurtosis | −1.56 | Kurtosis | 1.15 |

| Skewness | −1.12 | Skewness | −0.85 | Skewness | 0.06 | Skewness | −0.10 | Skewness | 1.47 |

| Minimum | 2.23 | Minimum | 6.10 | Minimum | 11.10 | Minimum | 16.80 | Minimum | 21.20 |

| Maximum | 5.90 | Maximum | 9.90 | Maximum | 15.90 | Maximum | 20.50 | Maximum | 26.40 |

| Variable | Total Count | N | Mean | SE Mean | St. Dev | Minimum | Median | Maximum | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (1/m) | 67 | 67 | 12.60 | 0.79 | 6.50 | 2.23 | 12.20 | 26.40 | 0.18 | −1.21 |

| Variable | N | Mean | SE Mean | St. Dev | Minimum | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (1/m) | 67 | 12.60 | 0.79 | 6.50 | 2.23 | 5.90 | 12.20 | 18.20 | 26.40 |

| Length (m) | 67 | 11.10 | 0.59 | 4.86 | 3.08 | 7.77 | 9.96 | 13.48 | 27.02 |

| Connectivity (FCA) | 67 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dasti, N.; Akram, M.S. Analyzing the Connectivity of Fracture Networks Using Natural Fracture Characteristics in the Khairi Murat Range, Potwar Region, Northern Pakistan. Geosciences 2025, 15, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120469

Dasti N, Akram MS. Analyzing the Connectivity of Fracture Networks Using Natural Fracture Characteristics in the Khairi Murat Range, Potwar Region, Northern Pakistan. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120469

Chicago/Turabian StyleDasti, Nasrullah, and Mian Sohail Akram. 2025. "Analyzing the Connectivity of Fracture Networks Using Natural Fracture Characteristics in the Khairi Murat Range, Potwar Region, Northern Pakistan" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120469

APA StyleDasti, N., & Akram, M. S. (2025). Analyzing the Connectivity of Fracture Networks Using Natural Fracture Characteristics in the Khairi Murat Range, Potwar Region, Northern Pakistan. Geosciences, 15(12), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120469