1. Introduction

The correct planning and management of the scientific value and the potential educational, touristic, and environmental uses of geodiversity have become increasingly important issues for geoconservation purposes at an international scale. Evidence of this is clearly reflected in various national and supranational organizations established in the last few decades for geoconservation and protection purposes, with agreements, conventions, and initiatives. This modern issue sheds light on the importance of geological heritage conservation and the challenges associated with its preservation and management. The conservation and protection of geoheritage are crucial in maintaining the Earth’s natural legacy and fostering a profound relationship between humans and the natural biotic and abiotic components.

Among the geodiversity, the geosites and the geodiversity sites are specific geographical areas subject to different protection, based on their scientific value (SV) [

1]. Indeed, the geosites having a high SV must be carefully managed and protected with priority for future generations, regardless of their potential educational (PEU) and touristic uses (PTU) and degradation risk (DR) [

1]. Indeed, the evaluation of the PEU and PTU is not requested for the quantitative assessment of a geosite but is supplementary [

1]. Differently, the geodiversity sites not having elevated SV, if provided with high PEU and PTU and preferably low DR, are available for geoeducation and geotourism purposes [

1].

In recent years, new approaches have provided schemes for the inventory, and quantitative assessment of geodiversity. These had the purpose of evaluating the scientific, educational, and touristic values, and the degradation risk, for a better and efficient sustainable, protection, and management of the geodiversity [

1]. Indeed, according to methods for the geodiversity inventory and assessment, the geodiversity in situ could be assigned to geosite or geodiversity site [

1].

In Italy, a vital role in managing and preserving the geoheritage is played by the national governmental agency ISPRA, which stands for “Higher Institute for Protection and Research Environmental” [

2]. The agency is responsible for regulating and monitoring environmental issues, such as air, water, and soil quality, as well as the preservation of natural resources and biodiversity. Regional authorities collaborate with this agency to guarantee that environmental regulations are being upheld and enforced throughout the country, ensuring a sustainable future for Italy’s geodiversity. However, this cooperation with the autonomous regions is carried out within specific regional regulatory frameworks.

At the regional scale, since the late 1990s, the Regional Administration of Sicily has been actively working to identify the geoheritage within its territory. To promote the establishment and management of these sites, the regional government formalized the regional law n. 25, 11 April 2012, outlining the “Rules for the recognition, cataloguing, and protection of geosites in Sicily” [

3]. The Sicilian government agency ARTA, which stands for “Regional Department for Land and Environment”, was entrusted with the responsibility of establishing a Regional Catalog of Geosites of Sicily [

3,

4]. The catalog was based on a set of criteria and guidelines for the management and protection of geosites. To ensure that the identification and definition of a single geosite were based on sound scientific principles, a Centre of Documentation on Geosites and a Technical and Scientific Committee on Geosites were established [

3,

4]. The committee comprised delegates from the Regional Administration, the Regional Professional Order of Geologists, and the Academic Institutions. The committee was responsible for supervising the data analysis and definition of the single geosites. As a consequence, a significant action for the protection of the geodiversity was carried out, deciding to include all the geodiversity falling down in the Sicilian natural reserves in the Regional Catalog of the Geosites. In this catalog, the following information was provided for over two hundred geosites [

3,

4], as follows:

Name of the geosite;

Name of the reserve;

Institution of the reserve;

Municipality;

Province;

Type of scientific interest (geo–history, hydrogeology/hydrology, karst, geomorphology, mineralogy, palaeontology, sedimentology, speleology, stratigraphy, structural geology, and vulcanology);

Grade of scientific interest (local, regional, national, and global);

Geosite category (punctual, linear, areal, and section);

Elements forming the geosite (single or multiple);

Geosite geographic coordinates.

Most of them regarded underground karst forms [

5] and cover an area extending 25.832 km

2.

On the basis of the above, the geodiversity preserved in the areas of the Sicilian natural reserves and reported in the Regional Catalog of Geosites of Sicily, being a priori classified as geosite, could also correspond to a geodiversity site. The difference in the management of geosites and geodiversity sites stays in the priority of the protection actions. Within this framework, another emerging criticism was related to the absence for some of these Sicilian geosites of a scientific report or inventory supporting their attribution to geosites.

With this in mind, the geo-biodiversity, preserved for a long time in the natural oriented reserve of the “Cape Peloro Lagoon” at Messina (Sicily, southern Italy), was carefully investigated in order to provide the geological and structural framework, the inventory, and quantitative assessment of the two Global geosites of the Lake Faro (LF) and Lake Ganzirri (LG) established in the Cape Peloro coastal lagoon (CPCL) [

3,

4]. These activities were aimed to verify if, nowadays, it is scientifically sound to continue to consider the geodiversity of the LF and LG as Global geosites [

3,

4]. Moreover, considering that the Mediterranean coastal lagoons are also particularly important because of their historical, social, ecological, touristic, and economic relevance, particular attention was also devoted to establishing what initiatives could be carried out in the future to enhance the LFs and LGs scientific, potential education, and touristic values, reducing the degradation risk and protecting them by any possible “pharaonic” infrastructure (as the Messina bridge) that would irreversibly prejudice the integrity of these protected areas for their geodiversity and biodiversity for a long time.

3. Geological and Structural Setting

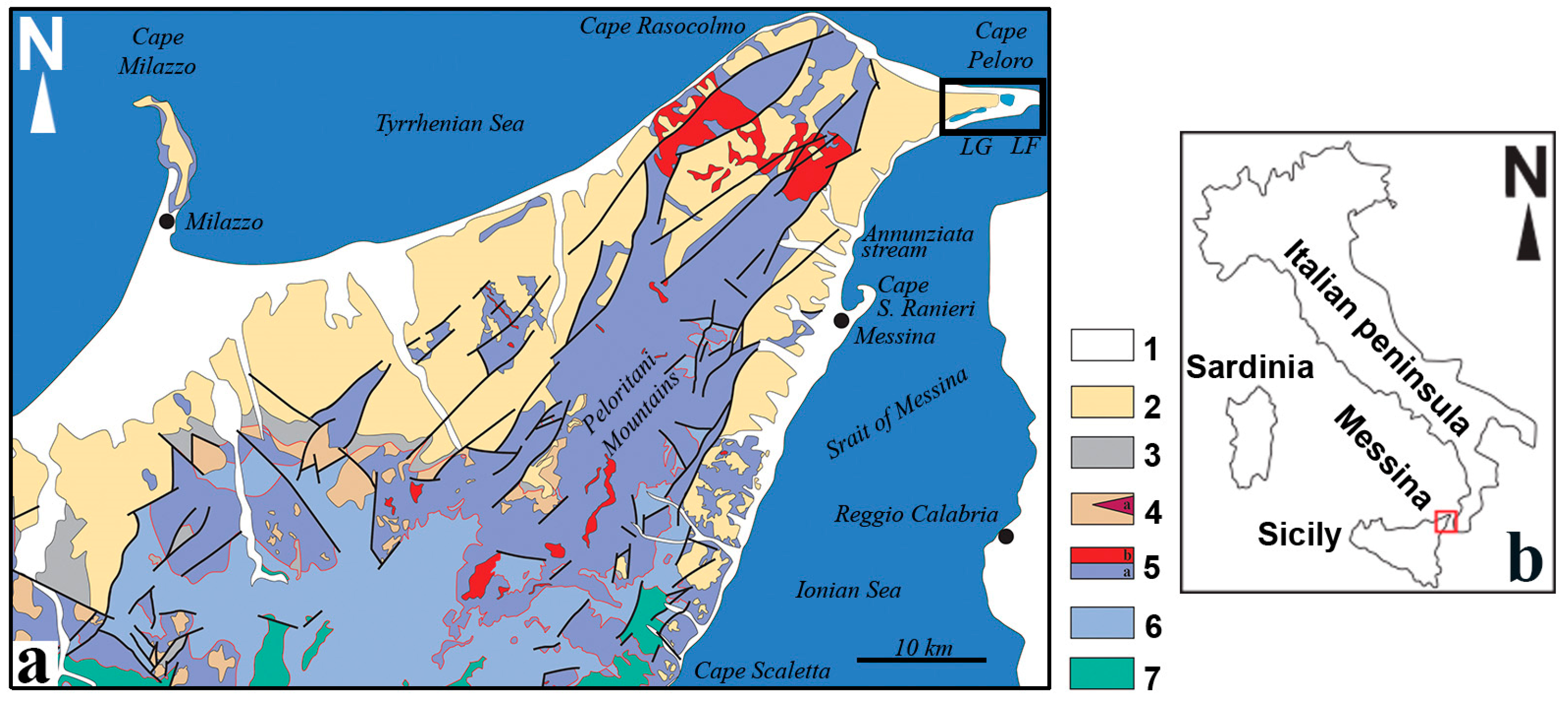

The CPCL is located in the low–relief coastal plain present on the NE edge of the Peloritani Mountains (

Figure 2). The Peloritani chain is formed by a thrust pile (

Figure 2) extending from Cape Peloro to the Taormina–Sant’Agata tectonic line [

41,

42,

43,

44]. The units are mainly composed of Variscan crystalline rocks [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50] and some of them preserve remnants of Mesozoic–Cenozoic sedimentary covers [

50]. Basements are made up of intrusive and metamorphic rocks showing high- to low-grade Variscan metamorphism, from the top to the base of the thrust pile [

42]. An exception is represented by the Alì–Montagnareale Unit, being composed of a post-Varican sequence affected by Alpine anchimetamorphism [

50] or by the Aspromonte and Mela Units, being devoid of sedimentary cover [

41,

42]. The thrust pile is sealed by thrust-top deposits, which are middle–upper Burdigalian in age [

42]. The strong late Miocene post-orogenic uplift of the chain, which is still active, enhanced a significant erosion of the crystalline rocks and the consequent deposition of siliciclastic sediments [

41].

The CPCL faces the natural split–peninsula of Cape Peloro, a triangular-shaped coastal area bounded by two coasts: the E–W trending Tyrrhenian coast and the ENE–WSW trending Ionian coast (

Figure 2). The CPCL represents the ending edge of the Strait of Messina [

51,

52] and its substrate is formed of Quaternary siliciclastic deposits represented by lower to middle Pleistocene deltaic–marine sediments (the Messina Fm.) and middle to upper Pleistocene marine terraces [

53] (

Figure 2). These latter also compose the hills surrounding the lagoon and the substrate of the Strait of Messina, as shown by offshore seismic profiles [

54].

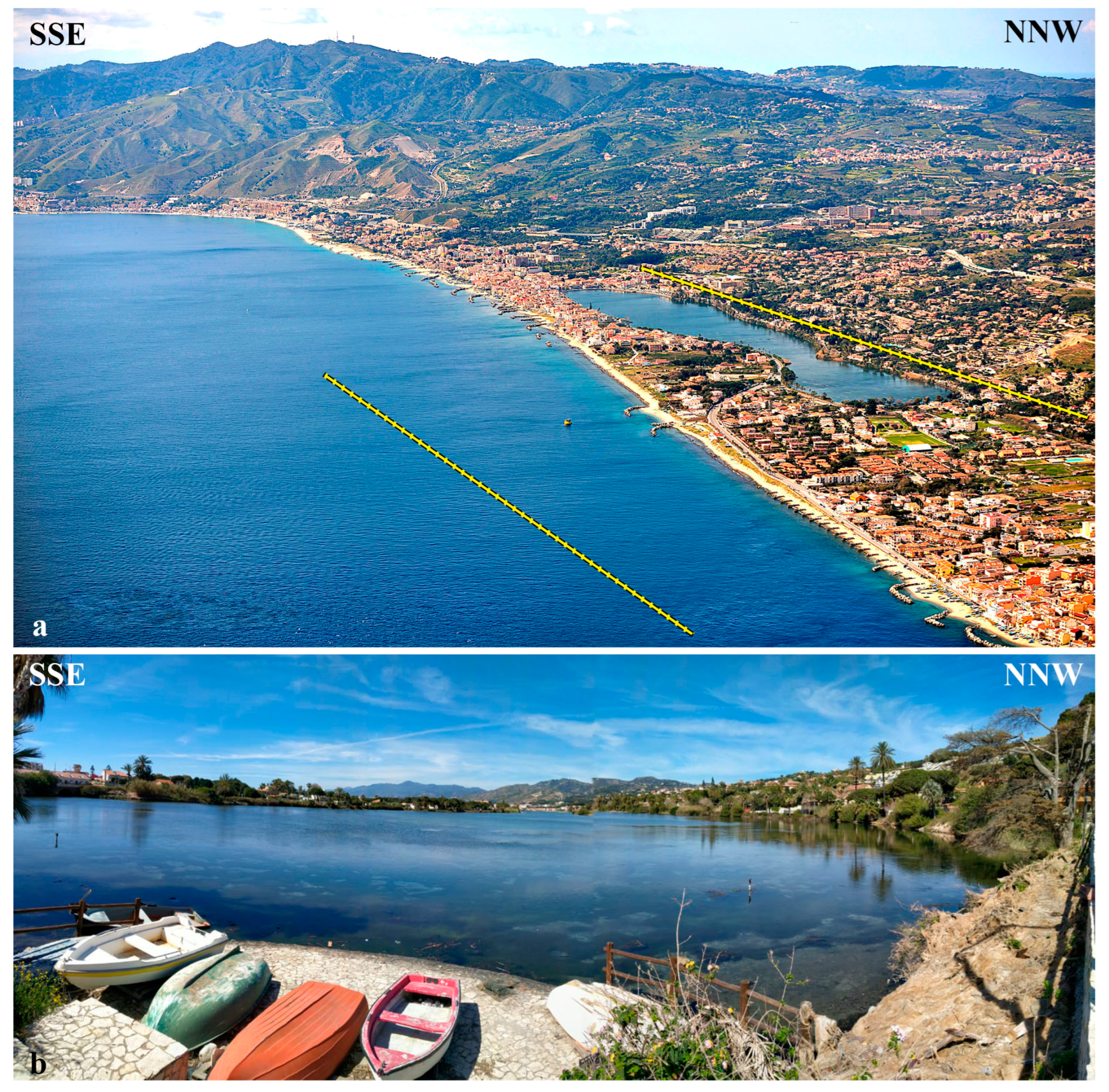

The CPCL

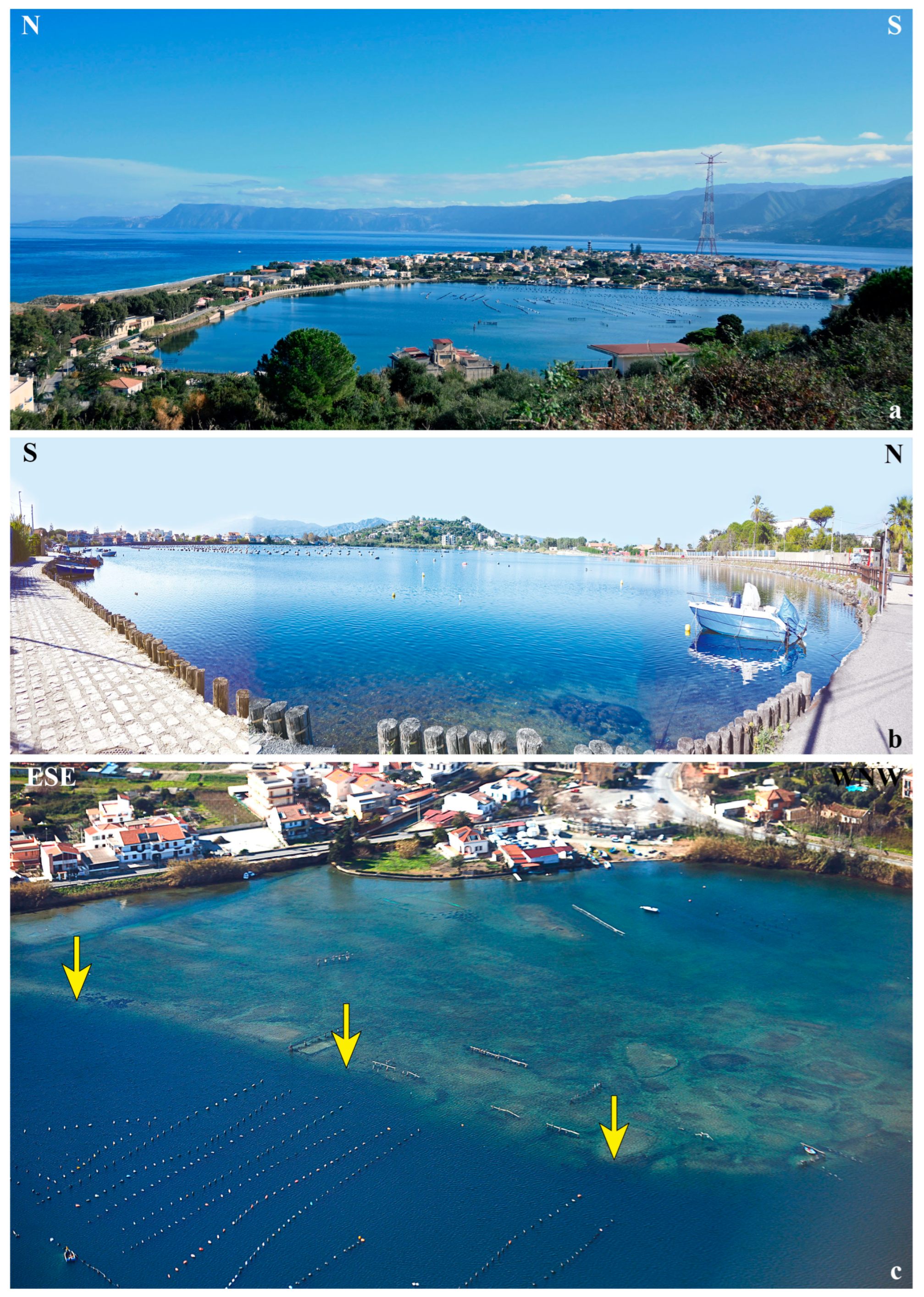

The CPCL is included in the densely populated coastal villages of Ganzirri and Torre Faro. The coastal lagoon mainly consists of brackish water basins with remnants of sand dunes. Nowadays, the existing basins are two, the coastal LF and LG. These are included in the lagoon and are officially considered a unique brackish environment with distinctive geological morpho-structures, flora, and fauna (a sanctuary for migratory birds and endemic mollusks).

The LF is a small brackish coastal lagoon with a sub-circular/octahedral shape. Its surface extends for about 263,600 m2 with a maximum depth of about 28 m on the eastern side of the lake. Two canals connect the brackish waters of the LF with the Ionian and Tyrrhenian Sea. Another canal connects the two lakes.

The LG is a narrow brackish coastal lagoon with an ENE–WSW trending elongated shape, parallel to the Ionian coast. The area is subdivided into two sub-basins covering a surface of about 338,400 m2. The LG shows a 7 m maximum depth and receives both underground and Sea waters, the latter are from two canals connected with the Ionian Sea.

Before the 1800, the lakes were not connected to the sea and a third lake, the Lake Margi (marsh), existed among the LF and LG. During the successive construction of the canals, the Lake Margi was infilled by the dug sediments and reclaimed. In the past, a salina extended in the western side of the LF and among the two sub-basins of the LG.

For the natural peculiarities and rarities, since 1979, the CPCL was included in the Special Protection Zones (Directive of the European Commission, 79/409/CEE [

55]) and in 1992 in the Sites of Community Importance (Directive of the European Commission, 92/43/CEE of 21 May 1992 [

56]) (Rete Natura 2000). In addition, the CPCL was also declared, according to declaratory provision 1342/88, “Heritage of ethnic–anthropological interest”, due to traditional working and productive activities related to aquaculture, specifically mussels, clams, and cockles farming.

The CPCL belongs to several different private owners, but after 2001, when it was also established as an Oriented Natural Reserve by the Regional Administration of Sicily, it was managed by the Metropolitan City of Messina [

57].

Finally, since 2015, after the disposals of the Sicilian Region, the geodiversity contained in the CPCL was ascribed to two areal geosites (

Figure 3), the only ones to be considered of Global interest in the insular territory of Messina. For their significant morpho–tectonic scientific value and uniqueness, the following geosites were denoted:

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. The Quantitative Assessment of Geodiversity

Consequently, the LF’s and LG’s geodiversity resulted in a geosite, being the SV provided with high score in both sites (

Table 5 and

Table 9). Indeed, the study morpho-structures resulted in key localities provided with SV indicators of representativeness, geological diversity, and rarity, to protect with priority, being clear and unequivocal examples of the Earth’s geological history and evolution of the Quaternary tectonic coastal lagoons. Regardless, activities for further improvement in the SV and the reduction in the DR could be carried out in the near future for the consequent relapses. The SV could benefit from an increasing score for scientific knowledge, given that the papers dedicated to this geodiversity are actually very scarce. For reducing the DR, the indicators “Proximity to areas/activities with potential to cause degradation” could be reduced in value, implementing the actions to reduce the cause of environmental degradation (for example, allowing vehicular traffic only to electricity cars and boats at low environmental impact) and increasing the activities of control of the competent authorities to protect geodiversity and biodiversity (for example, with the installation of permanent video cameras). In such a way, the consequences of poaching fishermen, notwithstanding the interdiction to fish, could be better contrasted.

With regard to the scenery of the lagoon, the LF could especially improve the level of quality if the actual structures used by the mollusk farmers (such as buoys, poles, and ropes) were substituted by smallest size and/or impacting materials.

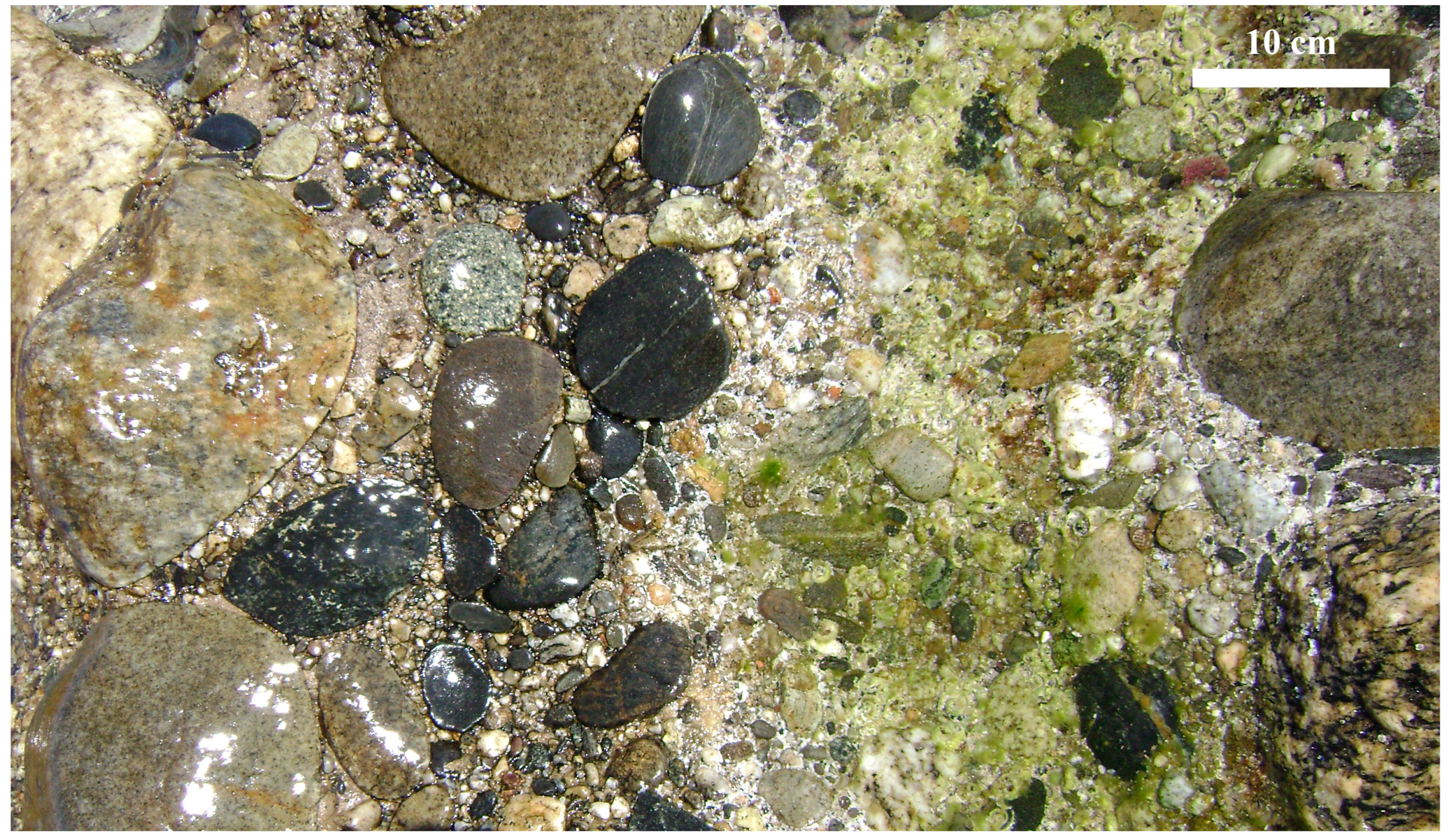

From an environmental point of view, the necessity to dispose of several actions to reduce/solve different criticisms found in the CPCL arose. A major control of the discharge waters in the lakes should be necessary. The construction and demolition materials (bricks and tiles) illegally abandoned in the past along the accessible lake coasts should be removed especially in the LF bottom. It seems useful to underline that recent research carried out in the CPCL pre-reserve areas (Ionian and Tyrrhenian coasts) reported the occurrence in the beach deposits of significant amounts of asbestos cement fragments associated with construction and demolition materials, especially on the Ionian coast [

51,

52].

Finally, the significant geodiversity recognized along the coast of the natural oriented reserve of Cape Peloro and represented by deformed beachrocks, due to their rarity, could be included in the geoheritage management and inventoried in the geosites of the CPCL, extending the protection of the coastland also sea-ward, nearshore.

5.2. Geoeducation and Geotourism

In the future, it could be possible to improve activities devoted to geoeducation and geotourism, considering the high scores of the PEU and PTU of the study LF and LG. Both uses could benefit from dedicated panoramic sites for observing the impressive scenery of the lakes (

Figure 8).

Panoramic locations to observe the geosite morpho-structures could be planned on the neighboring hill (LF: at 55 m a.s.l. in proximity of the five–a–side football field, coordinates 38°16′8.36″ N–38°16′8.36″ N; LG: at 80 m a.s.l. in proximity of the panoramic street, coordinates 38°15′59.13″ N–15°36′57.38″ E). Wooden turrets could be disseminated along the perimeter of both lakes. In particular, the capable fault present in the LF could be observed by researchers, students, and tourists from these turrets or along the existing pathway surrounding the lake. Observations could be also carried out during rowing boat trips or snorkeling/scuba diving activities at low impact along the fault scarp for limited numbers of stakeholders (if agreed and permitted by the director of the reserve).

Analogously, different geotrails could be also planned along the Ionian and Tyrrhenian shoreline, in order to observe the beachrocks cropping out from Torre Faro to Ganzirri onshore or snorkeling/scuba diving activities to observe the submerged beachrocks (

Figure 4a). These activities could be also extended in the surroundings of the Messina port, where evidence of the ancient extraction of mills of beachrocks is evident.

Finally, a geoeducation and geotouristic center organized by the University of Messina with the cooperation of both the reserve and the environmental associations could be planned to promote the bio–geodiversity of the lagoon, disseminating their knowledge.

5.3. Criticisms and Risks for the Geoheritage

The main risks of deterioration, degradation, and vulnerability are related to anthropic actions.

The Messina bridge project that is under planning procedures in the natural protected reserve of CPCL represents an actual serious criticism of the geoconservation of the study geoheritage. Urgent actions should be necessary and strongly promoted by the competent authorities, especially at the EU scale, also with the support of the university researchers and the global governmental and non-governmental environmental organizations and agencies (UNESCO, International Union for Conservation of Nature, European Environment Agency, Coastwatch Europe, etc.) for the protection and conservation of the geo-biodiversity maintained in the LF and LG Global geosites of the coastal lagoon with the related marine and continental fauna and flora and the coupled ethno-anthropological traditions. The realization of such infrastructures in a protected area, further to being in contrast with the regulations and laws devoted to defending the protected natural areas and geo-biodiversity, would negatively modify the values of the indicators used for the quantitative assessment of the studied global geosites. Indeed, the existing natural balances between biotic and abiotic components can be altered by the construction of infrastructures which, in addition to the risks linked to the survival of the structure itself, entail a certain and perhaps irreversible modification of the natural equilibria.

The interdiction to build significant infrastructures in a protected area should be a normal conduct to be adopted in advanced countries. It also seems useful and proper to underline in this peculiar historical moment that in Italy, it is not permitted to construct in the proximity (respect zones) of the capable faults. In the project for the Messina bridge, the infrastructures on both sides of the Strait of Messina should fall in areas crossed by capable faults as reported by the ISPRA in the official database of active capable faults of the Italian territory (project ITHACA) [

77]. One of these macroscale capable faults, belonging to the Scilla–Ganzirri normal fault system, bounds the Ionian coast just in front of the LG, as observed in the offshore seismic profiles by Doglioni et al. [

54] (

Figure 4a). Another macroscale capable fault belonging to the same system, observed in onshore seismic profiles [

61], bounds the LG (

Figure 4a,c). Moreover, recent data [

76] and unpublished data that are the objects of an ongoing investigation showed the presence of a diffused array of mesoscale-capable normal faults affecting the Quaternary deposits present in the CPCL surroundings.

5.4. Final Remarks

The actual criticisms that could irreversibly affect the environmental equilibria as well as the existing risks and the possible actions of redevelopment of the CPCL should be seriously considered and faced.

Any geoconservation strategy is essential for geodiversity protection from environmental damages or anthropic aggressions, being vital for the dissemination of knowledge for the next generations of researchers, students, and stakeholders. The scores attributed to the SV indicators (representativeness, key locality, geological diversity, and rarity) of the CPCL justify the attribution of the LF and LG of the CPCL to Global areal geosites. The authors fully agree with the previous decision of the Sicilian Region to reserve the maximum level of protection for these sites and the establishment of the maximum priority in their management.

Moreover, evaluating that the LF and LG belong to the following:

- (i)

Oriented Nature Reserves;

- (ii)

Special Protection Areas (Directives of the European Commission);

- (iii)

Sites of Community Importance (Directives of the European Commission);

- (iv)

Assets of ethno-anthropological interest,

It seems opportune to consider the CPCL as a possible candidate for being included in the list of UNESCO natural sites. This action could strengthen their status of “untouchable natural heritage of the humanity”, further helping to prevent any future environmental/anthropic aggression/aggressiveness to the significant geo-biodiversity of the CPCL.