From Geohistory to the Future: A Tribute to the Youthful Palaeontological Studies at Gravina in Puglia of Arcangelo Scacchi (1810–1893), the First Modern Geoscientist in the MurGEopark (aUGGp, Southern Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The MurGEopark: The Geological Reason for the aUGGp Nomination

3. Geological Setting of Gravina in Puglia and Its Surroundings

4. Arcangelo Scacchi: Life and Scientific Works of the First Modern Geoscientist of the MurGEopark

4.1. A Brief Biography

4.2. A Polyhedric Scientist and a Reference Point for the Geologists of the XIX Century

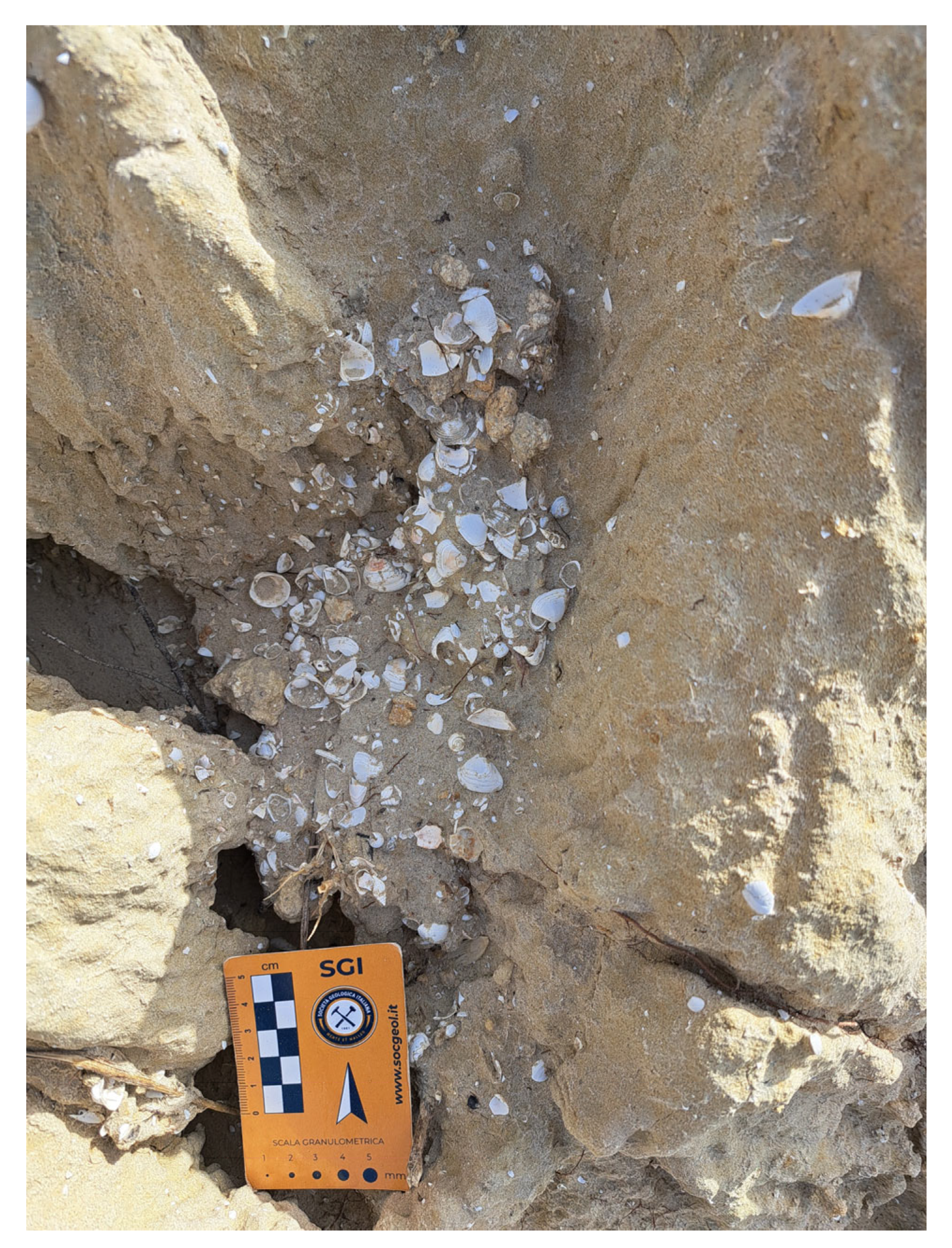

4.3. The Youthful Palaeontological Studies in Gravina in Puglia: A Still Valid Scientific Work

“…. e mettondoci ad esaminare…ci accorgeremo che quattro ben distinte formazioni sono come in un sol punto riunite”:

- (1)

- “… la più antica di esse, ossia l’inferiore è di calce carbonata compatta a finissima grana…Essa è la stessa calce carbonata di cui son formate le Murge…”,

- (2)

- “… la seconda formazione è di tufo composto di minuti pezzetti di conchiglie zoofiti ed echini…”,

- (3)

- la terza è composta da “… sabbia e ciotoli di diaspro…”,

- (4)

- la quarta ed ultima formazione è costituita da argilla figulina detta volgarmente creta…”.

[“… and upon examining it…we will realise that four clearly distinct formations are united as if in a single point (literal translation, probably meaning: ‘may be observed together in a single locality’).”

- (1)

- “The oldest of these, namely the lower one, consists of very fine-grained hard calcareous lime… It is the same calcareous lime that forms the Murge”.

- (2)

- “The second formation is made of tufa composed of thin fragments of zoophyte shells and sea urchins”.

- (3)

- “The third is composed of sand and pebbles of jasper” (probably meaning chert pebbles).

- (4)

- “The fourth and final formation is made up of clay for terracotta pots, commonly known as ‘creta’…”]

5. A Temporary Exhibition as a Tribute from His Town to the Scacchi Heritage

“E però avrei desiderato di far noto a’ miei concittadini quanta attenzione essa meriti quella feconda regione dagli studiosi delle naturali scienze, se tutte avessi potuto loro venir mostrando quelle cose che mi si è porto il destro di osservare. Ma richiedendo un tal lavoro miglior agio di quel che mi è dato godere, mi starò contento a toccar solo delle conchiglie e di alcuni zoofiti trovasi fossili nelle vicinanze di Gravina…”.

[“And therefore, I would have liked to let my fellow citizens know how much attention that fertile region deserves from the students of natural sciences, if I had been able to show them everything that I have had the opportunity to observe. However, as such work requires better facilities than I currently have at my disposal, I will be content to discuss only the shells and some of the zoophytes found in the vicinity of Gravina…”].

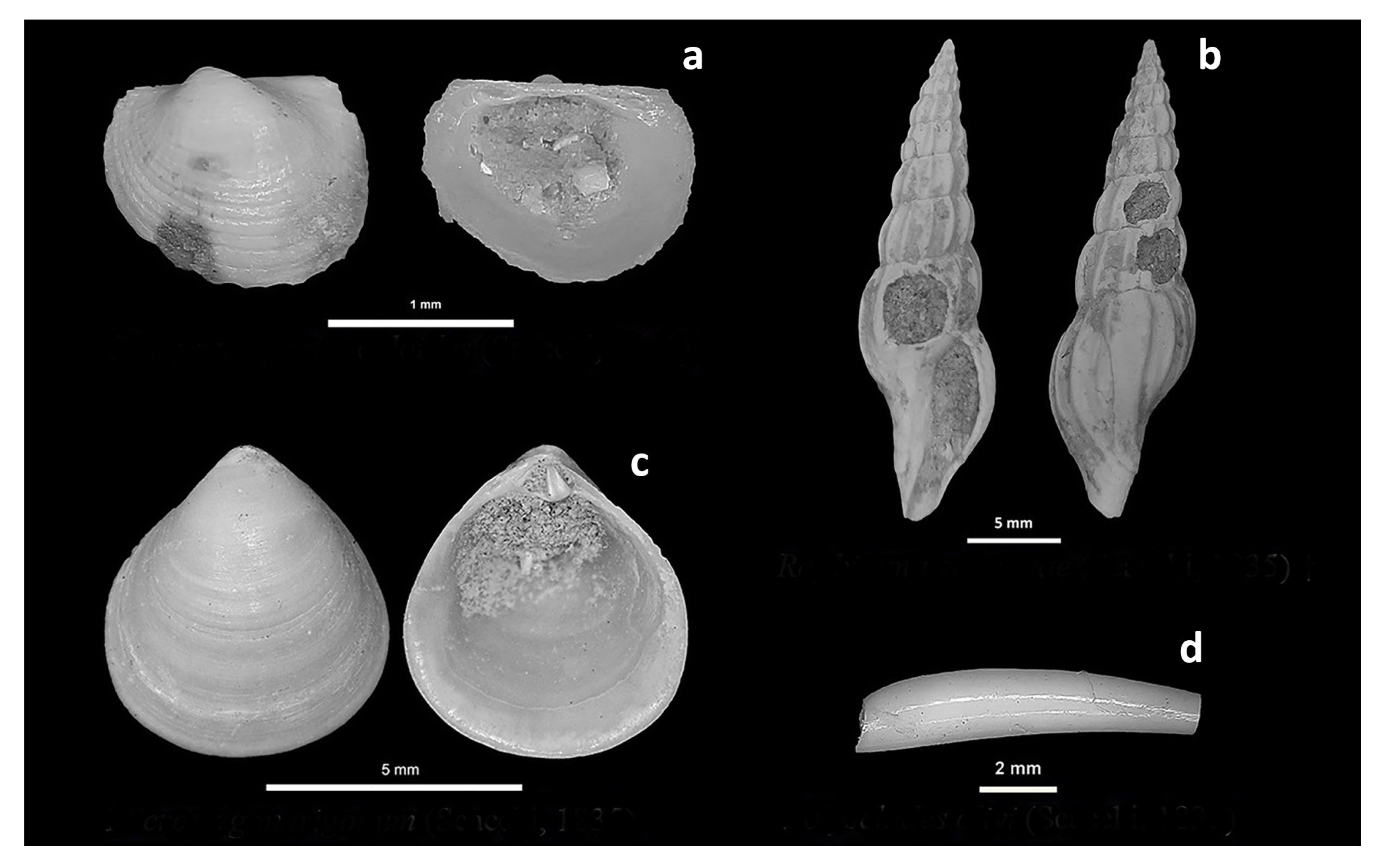

6. The Importance of Studying and Exposing the Recollected Scacchi Specimens

7. 3D Digital Models: An Alternative to the Physical Exposition of the Palaeontological Collection of Scacchi and a Modern Tribute to This Illustrious Geoscientist

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lippolis, E.; Sabato, L.; Spalluto, L.; Tropeano, M. Geotourism around Poggiorsini: Unexpected Geological Elements for a Sustainable Tourism in Internal Areas of Murge (Puglia, Southern Italy). Rend. Online Soc. Geol. Ital. 2023, 59, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropeano, M.; Caldara, M.A.; De Santis, V.; Festa, V.; Parise, M.; Sabato, L.; Spalluto, L.; Francescangeli, R.; Iurilli, V.; Mastronuzzi, G.A.; et al. Geological Uniqueness and Potential Geotouristic Appeal of Murge and Premurge, the First Territory in Puglia (Southern Italy) Aspiring to Become a UNESCO Global Geopark. Geosciences 2023, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Geoparks Council Unveils 15 New Geopark Nominations. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-global-geoparks-council-unveils-15-new-geopark-nominations (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Pieri, P. Principali Caratteri Geologici e Morfologici Delle Murge. Murgia Sotter. 1980, 2, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sabato, L.; Tropeano, M.; Festa, V.; Longhitano, S.G.; dell’Olio, M. Following Writings and Paintings by Carlo Levi to Promote Geology Within the “Matera-Basilicata 2019, European Capital of Culture” Events (Matera, Grassano, Aliano—Southern Italy). Geoheritage 2019, 11, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, V. Cretaceous Structural Features of the Murge Area (Apulian Foreland, Southern Italy). Ecol. Geol. Helv. 2003, 96, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Martinis, B. Sulla Tettonica Delle Murge Nord-Occidentali. In Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Rendiconti della Classe di Scienze Fisiche, Matematiche e Naturali; Tipografo dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei: Roma, Italy, 1961; Volume 31, pp. 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Iannone, A.; Pieri, P. Caratteri Neotettonici Delle Murge. Geol. Appl. Idrogeol. 1982, 18, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Tropeano, M.; Pieri, P.; Moretti, M.; Festa, V.; Calcagnile, G.; Del Gaudio, V.; Pierri, P. Quaternary Tectonics and Seismotectonic Features of the Murge Area (Apulian Foreland, SE Italy)|Tettonica Quaternaria Ed Elementi Dl Sismotettonica Nell’area Delle Murge (Avampaese Apulo). Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 1997, 10, 543–548. [Google Scholar]

- Ricchetti, G.; Ciaranfi, N.; Luperto Sinni, E.; Mongelli, F.; Pieri, P. Geodinamica Ed Evoluzione Sedimentaria e Tettonica Dell’avampaese Apulo. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1988, 41, 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Patacca, E.; Scandone, P. Il Contributo Degli Studi Stratigrafici Di Superficie e Sottosuolo Alla Conoscenza Dell’Appennino Lucano. In Proceedings of the Atti del Congresso Ricerca, Sviluppo e Utilizzo delle Fonti Fossili: Il Ruolo del Geologo, Potenza, Italy, 30 November–2 December 2013; pp. 97–153. [Google Scholar]

- Tropeano, M.; Sabato, L.; Pieri, P. Filling and Cannibalization of a Foredeep: The Bradanic Trough, Southern Italy. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2002, 191, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropeano, M.; Sabato, L.; Pieri, P. The Quaternary «Post-Turbidite» Sedimentation in the South-Apennines Foredeep (Bradanic Trough-Southern Italy). Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2002, 1, 449–454. [Google Scholar]

- Azzaroli, A.; Perno, U.; Radina, B. Note Illustrative della Carta Geologica d’Italia, F°188 “Gravina Di Puglia”; Poligrafica & Cartevalori: Ercolano, Italy, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Pieri, P.; Sabato, L.; Tropeano, M. Significato Geodinamico Dei Caratteri Deposizionali e Strutturali Della Fossa Bradanica Nel Pleistocene. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1996, 51, 501–515. [Google Scholar]

- Sabato, L. Delta Calcareo Terrazzato Nella Calcarenite Di Gravina (Pleistocene Inferiore) (Minervino, Murge Nord-Occidentali). Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1996, 51, 517–526. [Google Scholar]

- Sabato, L.; Tropeano, M.; Pieri, P. Problemi Di Cartografia Geologica Relativa Ai Depositi Quaternari Del F° 471 “Irsina”. Il Conglomerato Di Irsina: Mito o Realtà? Il Quat. Ital. J. Quat. Sci. 2004, 17, 391–404. [Google Scholar]

- Doglioni, C.; Mongelli, F.; Pieri, P. The Puglia Uplift (SE Italy): An Anomaly in the Foreland of the Apenninic Subduction Due to Buckling of a Thick Continental Lithosphere. Tectonics 1994, 13, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, M.; Festa, V.; Sabato, L.; Tropeano, M.; Doglioni, C. Interference between Apennines and Hellenides Foreland Basins around the Apulian Swell (Italy and Greece). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 133, 105300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropeano, M.; Sabato, L. Response of Plio-Pleistocene Mixed Bioclastic-Lithoclastic Temperate-Water Carbonate Systems to Forced Regressions: The Calcarenite Di Gravina Formation, Puglia, SE Italy. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2000, 172, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhitano, S.G.; Tropeano, M.; Chiarella, D.; Festa, V.; Mateu-Vicens, G.; Pomar, L.; Sabato, L.; Spalluto, L. The Sedimentary Response of Mixed Lithoclastic-Bioclastic Lower- Pleistocene Shallow-Marine Systems to Tides and Waves in the South Apennine Foredeep (Basilicata, Southern Italy) Tidalites Field Trips Special Volume—Tidalites, Matera, Field Trip T3. Geol. Field Trips Maps 2021, 13, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambonini, F. Arcangelo Scacchi e La Sua Opera Scientifica. Rend. Accad. Naz. Sci. XL 1930, XXIII, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- De Ceglie, R. Arcangelo Scacchi, Il” Vulcanico” Mineralogista. In Scienziati di Puglia, Secoli V a.C.—XXI d.C.; de Ceglia, F.P., Ed.; Adda: Bari, Italy, 2007; pp. 274–277. ISBN 9788880826811. [Google Scholar]

- De Ceglie, R. The Scientific Correspondence of Arcangelo Scacchi. Ann. Geophys. 2010, 52, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottana, A. Arcangelo Scacchi, Nel Bicentenario Della Nascita. Rend. Accad. Naz. Sci. XL 2010, XXXIV, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, L.; Scacchi, A. Della Regione Vulcanica Del Monte Vulture e Del Tremuoto Ivi Avvenuto Nel Di 14 Agosto 1851; Stabilimento Tipografico di Gaetano Nobile: Napoli, Italy, 1852. [Google Scholar]

- Cretella, M.; Crovato, C.; Crovato, P.; Fasulo, G.; Toscano, F. The Malacological Work of Arcangelo Scacchi (1810–1893). Part II: A Critical Review of Scacchian Taxa. Boll. Malacol. 2004, 40, 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cretella, M.; Crovato, C.; Fasulo, G.; Toscano, F. L’opera Malacologica Di Arcangelo Scacchi (1810–1893). Parte I: Biografia e Bibliografia. Boll. Malacol. 1992, 28, 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Scacchi, A. Notizie Intorno Alle Conchiglie Ed a’ Zoofiti Fossili Che Si Trovano Nelle Vicinanze Di Gravina in Puglia (Prima Parte). Ann. Civili Regno Due Sicilie 1835, 6, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Scacchi, A. Notizie Intorno Alle Conchiglie Ed a’ Zoofiti Fossili Che Si Trovano Nelle Vicinanze Di Gravina in Puglia (Seconda parte). Ann. Civili Regno Due Sicilie 1835, 7, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Belfiore, D. Ponte Di Gravina.jpg. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ponte_di_Gravina.jpg (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- La Perna, R.; Lippolis, E. The Pleistocene Molluscan Fauna from Gravina in Puglia, 200 Years After Arcangelo Scacchi. In Paleodays 2019. La Società Paleontologica Italiana a Benevento e Pietraroja. Parte 1: Volume dei riassunti della XIX Riunione annuale SPI (Società Paleontologica Italiana); Rook, L., Pandolfi, L., Eds.; Ente GeoPaleontologico di Pietraroja (Benevento): Pietraroja, Italy, 2019; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Scacchi, A. Catalogus Conchyliorum Regni Neapolitani Quae Usque Adhuc Reperit A. Scacchi; Typis F. Xaverii Tornese: Napoli, Italy, 1857. [Google Scholar]

- Scacchi, A. Notizie Geologiche Sulle Conchiglie Che Si Trovan Fossili Nell’isola d’Ischia e Lungo La Spiaggia Tra Pozzuoli e Monte Nuovo. In Antologia di Scienze Naturali; Piria, A., Scacchi, A., Eds.; Tipografia del Filiatre-Sebezio: Napoli, Italy, 1841; Volume 1, pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Settimana Del Pianeta Terra. Arcangelo Scacchi, Il Primo Geoscienziato Del Parco Nazionale Alta Murgia—Aspirante Geoparco UNESCO. Available online: https://www.settimanaterra.org/node/4344 (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Pages, K.N. The Protection of Jurassic Sites and Fossils: Challenges for Global Jurassic Science (Including a Proposed Statement on the Conservation of Palaeontological Heritage and Stratotypes). Riv. Ital. Paleontol. Stratigr. Stratigr. 2003, 110, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.H.; Pena dos Reis, R. Framing the Palaeontological Heritage Within the Geological Heritage: An Integrative Vision. Geoheritage 2015, 7, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropeano, M.; Sabato, L.; Festa, V.; Capolongo, D.; Casciano, C.I.; Chiarella, D.; Gallicchio, S.; Longhitano, S.G.; Moretti, M.; Petruzzelli, M.; et al. “Sassi”, the Old Town of Matera (Southern Italy): First Aid for Geotourists in the “European Capital of Culture 2019”. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 2018, 31, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithsonian 3D. Available online: https://3d.si.edu/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Sketchfab. Natural History Museum Vienna. Available online: https://sketchfab.com/NHMWien (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Sketchfab. Lapworth Museum of Geology. Available online: https://sketchfab.com/LapworthMuseum (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Sketchfab. Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Available online: https://sketchfab.com/CMNH (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Sketchfab. Auckland Museum. Available online: https://sketchfab.com/aucklandmuseum/models (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- African Fossils. Available online: https://africanfossils.org/search (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Digital Atlas of Ancient Life. Available online: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Mallison, H.; Wings, O. Photogrammetry in Paleontology—A Practical Guide. J. Paleontol. Tech. 2014, 12, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Falkingham, P. Acquisition of High Resolution Three-Dimensional Models Using Free, Open-Source, Photogrammetric Software. Palaeontol. Electron. 2012, 15, 1T. Available online: https://palaeo-electronica.org/content/pdfs/264.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.A.; Rahman, I.A.; Lautenschlager, S.; Rayfield, E.J.; Donoghue, P.C.J. A Virtual World of Paleontology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herraiz, J.L.; Villena, J.A.; Vilaplana-Climent, A.; Conejero, N.; Cocera, H.; Botella, H.; García-Forner, A.; Martinez-Perez, C. The Palaeontological Virtual Collection of the University of Valencia’s Natural History Museum: A New Tool for Palaeontological Heritage Outreach. Span. J. Palaeontol. 2019, 34, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, R.P.; Sereno, P.C.; Vidal, D.; Baumgart, S.L. Reproducible Digital Restoration of Fossils Using Blender. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 833379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betocchi, U.; Madeddu, N. Stampa 3D: Una Nuova Risorsa per Gli Allestimenti Museali. In Museologia Scientifica Memorie; Bon, M., Trabucco, R., Vianello, C., Eds.; Associazione Nazionale Musei Scientifici: Firenze, Italy, 2016; Volume 15, pp. 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, M.J.; Perez, V.J.; Pirlo, J.; Narducci, R.E.; Moran, S.M.; Selba, M.C.; Hastings, A.K.; Vargas-Vergara, C.; Antonenko, P.D.; MacFadden, B.J. Applications of 3D Paleontological Data at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 600696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.H.; Carter, A.M. Defossilization: A Review of 3D Printing in Experimental Paleontology. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Kimura, Y. Museum Exhibitions of Fossil Specimens into Commercial Products: Unexpected Outflow of 3D Models Due to Unwritten Image Policies. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 874736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakis, M.; Trichopoulos, G.; Aliprantis, J.; Michalakis, K.; Caridakis, G.; Thanou, A.; Zafeiropoulos, A.; Sklavounou, S.; Psarras, C.; Papavassiliou, S.; et al. An Enhanced Methodology for Creating Digital Twins within a Paleontological Museum Using Photogrammetry and Laser Scanning Techniques. Heritage 2023, 6, 5967–5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francescangeli, R.; Monno, A. Tecnologie 3D per i Musei. Museol. Sci. Nuova Ser. 2010, 4, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sketchfab. ElioLippolis. Available online: https://sketchfab.com/ElioLippolis (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- 3DFlow Zephyr. Available online: https://www.3dflow.net/it/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Lippolis, E. La Fotogrammetria Come Strumento per Valorizzare e Preservare Collezioni Fossili: Un Esempio Applicato Ai Molluschi Pleistocenici Di Gravina in Puglia. In Il Patrimonio Culturale Pugliese. Ricerche, Applicazioni e Best Practices, Atti del II Congresso BENI CULTURALI IN PUGLIA, Volume 2 (Bari, 28–30 Settembre 2022); Edizioni Fondazione Pasquale Battista: 2023; pp. 48–52, ISBN 979-12-210-3581-0. Available online: https://www.fondazionepasqualebattista.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Atti-bbcc-2023_2.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Sutton, M.; Rahman, I.; Garwood, R. Techniques for Virtual Palaeontology; Sutton, M.D., Rahman, I.A., Garwood, R.J., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781118591130. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, J.A. The Use of Photogrammetric Fossil Models in Palaeontology Education. Evol. Educ. Outreach. 2021, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lippolis, E.; De Ceglie, R.; Francescangeli, R.; La Perna, R.; Sabato, L.; Tropeano, M. From Geohistory to the Future: A Tribute to the Youthful Palaeontological Studies at Gravina in Puglia of Arcangelo Scacchi (1810–1893), the First Modern Geoscientist in the MurGEopark (aUGGp, Southern Italy). Geosciences 2024, 14, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences14120343

Lippolis E, De Ceglie R, Francescangeli R, La Perna R, Sabato L, Tropeano M. From Geohistory to the Future: A Tribute to the Youthful Palaeontological Studies at Gravina in Puglia of Arcangelo Scacchi (1810–1893), the First Modern Geoscientist in the MurGEopark (aUGGp, Southern Italy). Geosciences. 2024; 14(12):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences14120343

Chicago/Turabian StyleLippolis, Elio, Rossella De Ceglie, Ruggero Francescangeli, Rafael La Perna, Luisa Sabato, and Marcello Tropeano. 2024. "From Geohistory to the Future: A Tribute to the Youthful Palaeontological Studies at Gravina in Puglia of Arcangelo Scacchi (1810–1893), the First Modern Geoscientist in the MurGEopark (aUGGp, Southern Italy)" Geosciences 14, no. 12: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences14120343

APA StyleLippolis, E., De Ceglie, R., Francescangeli, R., La Perna, R., Sabato, L., & Tropeano, M. (2024). From Geohistory to the Future: A Tribute to the Youthful Palaeontological Studies at Gravina in Puglia of Arcangelo Scacchi (1810–1893), the First Modern Geoscientist in the MurGEopark (aUGGp, Southern Italy). Geosciences, 14(12), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences14120343