Deterioration Processes on Prehistoric Rock Art Induced by Mining Activity (Arenaza Cave, N Spain)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

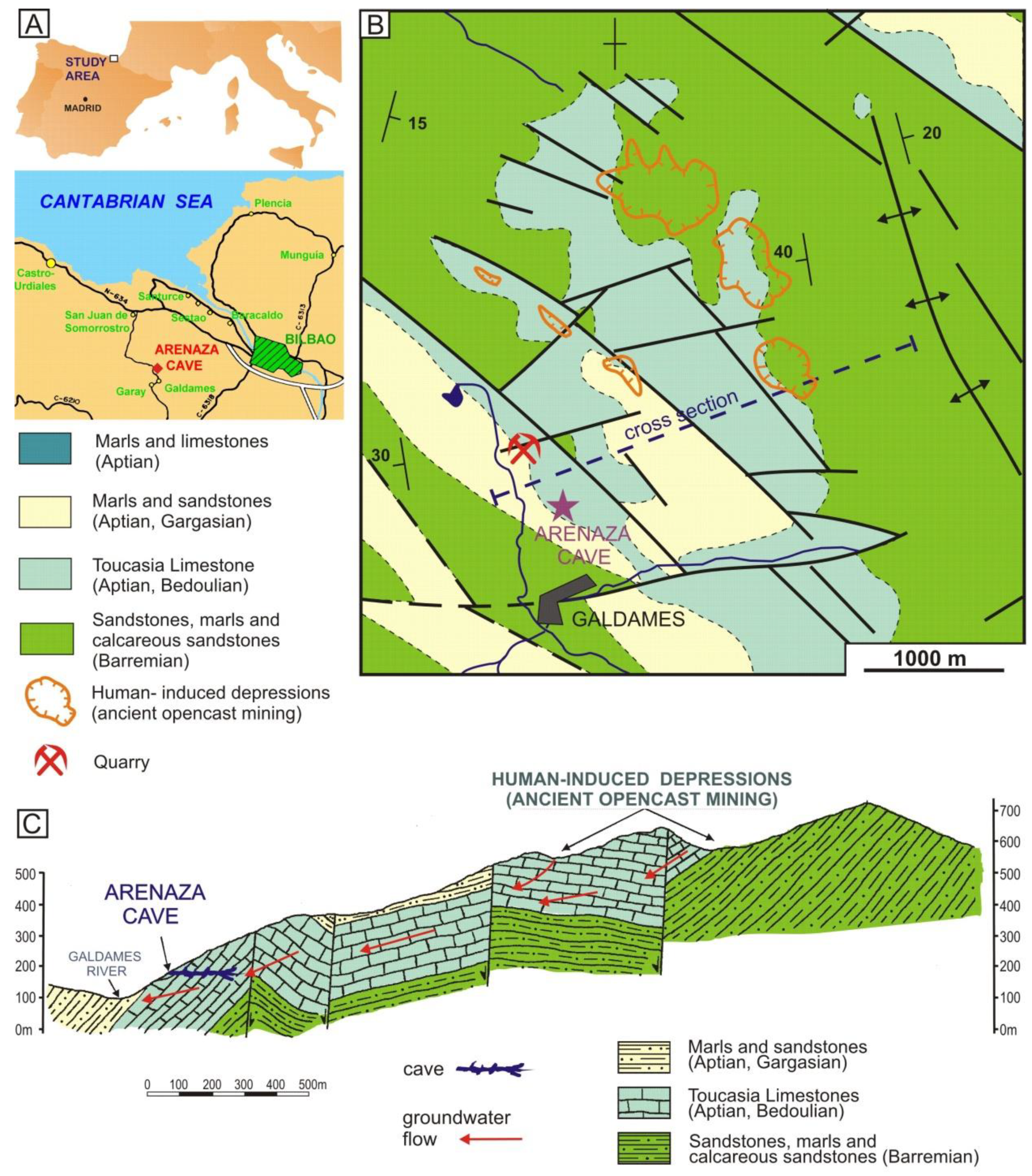

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Influence of Mining Activity in the Karstic System

- 1st Stage. Prior to the discovery of the paintings and related to mining prospecting work carried out in the first half of the 20th century, new galleries were opened and the morphological characteristics of other natural galleries were modified. Explosives were used for the opening of prospecting galleries from karstic conduits. Several alterations that modify the circulation of infiltration water are derived from these mining activities: (i) changes in the geomorphology of the cave, and (ii) fissuring of host limestone and/or joints and diaclases.

- 2nd Stage. Alterations subsequent to the discovery of the paintings, also related to mining activities in which explosives are used, due to the exploitation of aggregate quarries since the 1980s. Nowadays an active quarry for limestone aggregate extraction is located approximately 250–300 m from the Arenaza Cave. These limestones are the same that constitute the cave host rock. The effects produced by these activities are: (i) modifications in the karst morphology—the main karst collectors are now located in old natural depressions (dolines), which are remoulded by mining activities, and in artificial depressions (quarries), (ii) modification in both rate and direction of endokarstic water flow, even with openings of galleries to the outside and partial occlusion of others due to landslides, and (iii) the enlargement of host rock fissure network in the walls and floor of the cave by vibrations produced by blasting-induced vibrations.

4.2. Alteration Processes in the Cave Paintings

- A first phase of speleothems, on which the paintings are directly placed, made up of 1–3 mm-thick stalagmitic crusts that are mainly composed of calcite (92–96%) with low gypsum content (2–6%) (Figure 4A,B). They are formed by palisade calcite crystals that present dissolution textures on their surface. Locally, they show more complex textures with botryoidal aggregates that are rich in impurities (clays).

- A second phase of speleothems, located between the host rock and the first phase of speleothems (Figure 4C,D), mainly consisting of gypsum (95–97%) and smaller amounts of calcite and aragonite (<3%).

| Content (%) | Host Rock (Limestone) | 1st Phase Speleothem | 2nd Phase Speleothem (Fissure Infill) | 2nd Phase Speleothem (Surface Aggregate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 4.40 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 4.40 |

| Al2O3 | 1.40 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.42 |

| Fe2O3 + FeO | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| MgO | 0.75 | 1.74 | 1.51 | 2.65 |

| CaO | 51.91 | 58.23 | 57.86 | 52.12 |

| K2O | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| TiO2 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| P2O3 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| WL | 40.10 | 39.45 | 40.15 | 39.40 |

| Total | 99.91 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.04 |

| Calcite | 95 | 94 | 4 | 4 |

| Aragonite | <2 | <3 | - | 2 |

| Dolomite | <3 | - | - | - |

| Quartz | <5 | - | - | - |

| Clays | <5 | <3 | <5 | <5 |

| Gypsum | - | 3 | 96 | 95 |

- Loss of material (pigments) (Figure 2), due to leaching as result of surface (laminar) water circulation and/or natural condensation.

- Development of gypsum botryoidal concretions, which pick up and cause bulges in the paintings (Figure 4C,D); this process is poor-developed and seems to be modern.

- Contour scaling: Detachment of rock flakes that host cave paintings (Figure 5). There are two phases or stages in the detachment of scales or flakes: a poor-developed pre-painting phase and a recent post-painting phase that implies an important and irreversible degradation of the rock art. The size of the plates or flakes is centimetric, with thicknesses generally around 5 mm and less than 8 mm. Granular disintegration is commonly observed on the detachment surface of the flakes (Figure 5C). Growth of crystalline crusts related to both phases of the detachment processes can be observed.

5. Discussion

- I. Pre-mining phase. The paintings made on the different surfaces (host limestone and speleothems) suffer natural deterioration processes.

- II. Initial phase of mining activity. Mining labors lead to the enlargement of the initial host rock fissure network and an increase of the water flow rate on cave walls. This water flow favours leaching processes on cave paintings, selective dissolution of the gypsum fraction of the first phase speleothems, as well as further calcite cementation.

- III–IV. Active mining phase. Due to changes in the flow and the consequent modification of the hydrochemistry of the karst waters, the precipitation of crystalline gypsum aggregates occurs both in fissures and on the wall surfaces (second phase speleothems). Flake detachment is caused by crystallization pressure due to gypsum growth and by the vibration phenomena related to explosions in the nearby quarry.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cigna, A.A. Environmental management of tourist caves. Environ. Geol. 1993, 21, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, M. Procesos de alteración de soporte y pintura en diferentes cuevas con arte rupestre del norte de España: Santimamiñe, Arenaza, Altamira y Llonín. Mesa Redonda Hispano-francesa. Colombres-Asturias: 3 a 6 de junio de 1991. In La Protección y Conservación del Arte Rupestre Paleolítico; Fortea, J., Ed.; Consejería de Educación y Cultura: Oviedo, Spain, 1993; pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos, M.; Cañaveras, J.C.; Sánchez-Moral, S.; Sanz-Rubio, E.; Soler, V. Microclimatic characterization of a karstic cave: Human impact on microenvironmental parameters of a prehistoric rock art cave (Candamo Cave, northern Spain). Environ. Geol. 1998, 33, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañaveras, J.C.; Sánchez-Moral, S.; Soler, V. Protección y conservación de cavidades kársticas con arte rupestre. In Documentos del XIII Simposio de la Enseñanza de la Geología; Alfaro, P., Andreu, J.M., Cañaveras, J.C., Yébenes, A., Eds.; Instituto de Ciencias de la Educación. Univ.: Alicante, Spain, 2004; pp. 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cañaveras, J.C.; Cuezva, S.; Sanz-Rubio, E.; Sánchez-Moral, S. Definition of protection areas in a prehistoric art cave (Tito Bustillo cave, N Spain). In Heritage, Weathering and Conservation; Fort, R., Alvárez Buergo, M., Gómez-Heras, M., Vázquez-Calvo, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006; pp. 813–817. [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte, E.; Sánchez, M.A.; Foyo, A.; Tomillo, C. Geological risk assessment for cultural heritage conservation in karstic caves. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beynen, P.; Brinkmann, R.; van Beynen, K. A sustainability index for karst environments. J. Cave Karst Stud. 2012, 74, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moral, S.; Cañaveras, J.C.; Sanz-Rubio, E.; Soler, V.; Van Grieken, R.; Gysels, K. Inorganic deterioration affecting Altamira Cave. Quantitative approach to wall corrosion (solution etching) processes induced by visitors. Sci. Total Environ. 1999, 243, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Cuezva, S.; Jurado, V.; Fernández-Cortes, A.; Porca, E.; Benavente, D.; Cañaveras, J.C.; Sánchez-Moral, S. Paleolithic art in peril: Policy and science collide at altamira cave. Science 2011, 334, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacanette, D.; Large, D.; Ferrier, C.; Aujoulat, N.; Bastian, F.; Denis, A.; Jurado, V.; Kervazo, B.; Konik, S.; Lastennet, R.; et al. A laboratory cave for the study of wall degradation in rock art caves: An implementation in the Vézère area. J. Arch. Sci. 2013, 40, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerboni, A.; Villa, F.; Wu, Y.-L.; Solomon, T.; Trentini, A.; Rizzi, A.; Cappitelli, F.; Gallinaro, M. The Sustainability of Rock Art: Preservation and Research. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, J. The geomorphological impacts of limestone quarrying. Catena 1993, 15, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, J. (Ed.) Quarrying of limestones. In Encyclopedia of Cave and Karst Science; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 608–611. [Google Scholar]

- LaMoreaux, P.E.; Powell, W.J.; LeGrand, H.E. Environmental and legal aspects of karst areas. Environ. Geol. 1997, 29, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, W.H. Potential Environmental Impacts of Quarrying Stone in Karst. A Literature Review. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2001, OF-01-0484. Available online: http://geology.cr.usgs.gov/pub/ofrs/OFR-01-0484/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Ford, D.; Williams, P. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; 576p. [Google Scholar]

- Parise, M. The impacts of quarrying in the Apulian karst (Italy). In Advances in Research in Karst Media; Andreo, B., Carrasco, F., Durán, J.J., LaMoreaux, J.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 441–447. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, I.; Bodego, A.; Aranburu, A.; Arriolabengoa, M.; del Val, M.; Iriarte, E.; Abendaño, V.; Calvo, J.I.; Gárate, D.; Hermoso de Mendoza, A.; et al. Geological risk assessment for rock art protection in karstic caves (Alkerdi Caves, Navarre, Spain). J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortea, J. (Ed.) La Protección y Conservación del Arte Rupestre Paleolítico; Mesa Redonda Hispano-Francesa (Colombres, 1991); Servicio de Publicaciones de la Consejería de Educación, Cultura, Deportes y Juventud del Principado de Asturias: Oviedo, Spain, 1993; 191p. [Google Scholar]

- Fortea, J.; Hoyos, M. La table ronde de Colombres et les études de protection et conservation en Asturies réalisées de 1992 à 1996. Bull. Soc. Préhist. Ariège-Pyrénées 1999, 54, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano Diez-Canedo, A.; Fernández Alonso, O.; Eraso, A. Estudio hidroeológico de las calizas de Galdames. Jorn. Sobre Karst Eusk. 1986, I, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Geológico y Minero de España. Mapa Geológico de España, Bilbao 61 (25-1), Escala 1:50.000; Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Madrid, Spain, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos, M.; Sánchez-Moral, S.; Cañaveras, J.C.; Sanz Rubio, E. Informe Sobre la Delimitacion del Area de Protección Total de la CUEVA de Arenaza (Galdames, Vizcaya); Consejería de Educación y Cultura del Gobierno Vasco: Madrid, Spain, 1994; 12p. [Google Scholar]

- Gárate, D.; Jiménez, J.M.; Ortiz, J. El arte rupestre paleolítico de la cueva de Arenaza (Galdames, Bizkaia). Kobie (Paleoantropol.) 2000, 26, 5–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gárate, D. Nuevas investigaciones sobre el arte parietal paleolítico de la cueva de Arenaza (Galdames, Bizkaia). Munibe 2004, 56, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gárate, D.; Laval, E.; Menu, M. Étude de la matière colorante de la grotte d’Arenaza (Galdames, Pays Basque, Espagne). L’anthropologie 2004, 108, 251–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apellaniz, J.M. El Arte Prehistórico del País Vasco y sus Vecinos; Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Spain, 1982; 232p. [Google Scholar]

- RESOLUCIÓN de 5 de octubre de 2010, del Viceconsejero de Cultura, Juventud y Deportes, por la que se impulsa la tramitación del expediente de adaptación a las prescripciones de la Ley 7/1990, de 3 de julio, de Patrimonio Cultural Vasco de la declaración de la Cueva de Arenaza I de Galdames (Bizkaia) como Bien Cultural Calificado con la categoría de Conjunto Monumental, y se establece una nueva delimitación, una nueva descripción y un nuevo régimen de protección. Basque Official Gazette 2010, 207, 5959. Available online: https://www.euskadi.eus/y22-bopv/es/bopv2/datos/2010/10/1004959a.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- DECRETO 111/2012, de 19 de junio, por el que se adapta a las prescripciones de la Ley 7/1990, de 3 de julio, del Patrimonio Cultural Vasco, el expediente de Bien Cultural Calificado, con la categoría de Conjunto Monumental, a favor de la Cueva de Arenaza I de Galdames (Bizkaia), y se establece una nueva delimitación, una nueva descripción y un nuevo régimen de protección. Basque Official Gazette 2012, 128, 3000. Available online: https://www.euskadi.eus/y22-bopv/es/bopv2/datos/2012/07/1203000a.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- ICOMOS-ICS. Illustrated Glossary on Stone Deterioration Pattern. 2008. Available online: http://international.icomos.org/publications/monuments_and_sites/15/pdf/Monuments_and_Sites_15_ISCS_Glossary_Stone.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Sánchez-Moral, S.; Sanz-Rubio, E.; Soler, V. Análisis del estado de conservación de la roca soporte de las pinturas y registro y análisis de vibraciones de fondo en la Cueva de Urdiales. In Cueva Urdiales (Castro Urdiales, Cantabria); Montes, R., Muñoz, E., Morlote, J.M., Eds.; Ayuntamiento de Castro Urdiales: Cantabria, Spain, 2005; pp. 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Abella, R.; Sánchez-Moral, S. Registro de Vibraciones en la Cueva de Cobrante (Voto, Cantabria): Análisis de la Influencia de Obras Específicas de Perforación Dentro de su Área de Protección Total; Informe inédito para la empresa REE y la Consejería de Cultura, Turismo y Deporte de Cantabria: Cantabria, Spain, 2007; 9p. [Google Scholar]

- Control of Vibrations Made by Blasting. UNE 22-381-93; Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación: Madrid, Spain, 1993; 12p.

- RESOLUCIÓN de 18 de octubre de 2021, del Director de Calidad Ambiental y Economía Circular, por la que formula la declaración de impacto ambiental de la modificación del proyecto de explotación de la cantera Galdames II, ubicada en las concesiones de explotación de la Sección C) denominadas «Galdames II» n.º 12.793 y «Galdames II Ampliación» n.º 12.807, en el término municipal de Galdames (Bizkaia), promovido por Áridos y Canteras del Norte, S.A. Basque Official Gazette 2021, 227, 5828. Available online: https://www.euskadi.eus/y22-bopv/es/bopv2/datos/2021/11/2105828a.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Cañaveras, J.C.; Sánchez-Moral, S. Impacto ambiental del hombre en las cuevas. In Karst and the Environment; Carrasco, F., Durán, J.J., Andreo, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Despain, J.; Fryer, S. Hurricane crawl cave: A GIS-based cave management plan analysis and review. J. Cave Karst Stud. 2002, 64, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Elez, J.; Cuezva, S.; Fernández-Cortes, A.; García-Antón, E.; Benavente, D.; Cañaveras, J.C.; Sánchez-Moral, S. A GIS-based methodology to quantitatively define an Adjacent Protected Area in a shallow karst cavity: The case of Altamira cave. J. Environ. Manage. 2013, 118, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.A.; Foyo, A.; Tomillo, C.; Iriarte, E. Geological risk assessment of the Altamira Cave: A proposed Natural Risk Index and Safety Factor for the protection of prehistoric Caves. Eng. Geol. 2007, 94, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cañaveras, J.C.; Muñoz-Cervera, M.C.; Sánchez-Moral, S. Deterioration Processes on Prehistoric Rock Art Induced by Mining Activity (Arenaza Cave, N Spain). Geosciences 2022, 12, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12080309

Cañaveras JC, Muñoz-Cervera MC, Sánchez-Moral S. Deterioration Processes on Prehistoric Rock Art Induced by Mining Activity (Arenaza Cave, N Spain). Geosciences. 2022; 12(8):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12080309

Chicago/Turabian StyleCañaveras, Juan Carlos, María Concepción Muñoz-Cervera, and Sergio Sánchez-Moral. 2022. "Deterioration Processes on Prehistoric Rock Art Induced by Mining Activity (Arenaza Cave, N Spain)" Geosciences 12, no. 8: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12080309

APA StyleCañaveras, J. C., Muñoz-Cervera, M. C., & Sánchez-Moral, S. (2022). Deterioration Processes on Prehistoric Rock Art Induced by Mining Activity (Arenaza Cave, N Spain). Geosciences, 12(8), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12080309