Assessment of Ground Instabilities’ Causative Factors Using Multivariate Statistical Analysis Methods: Case of the Coastal Region of Northwestern Rif, Morocco

Abstract

1. Introduction

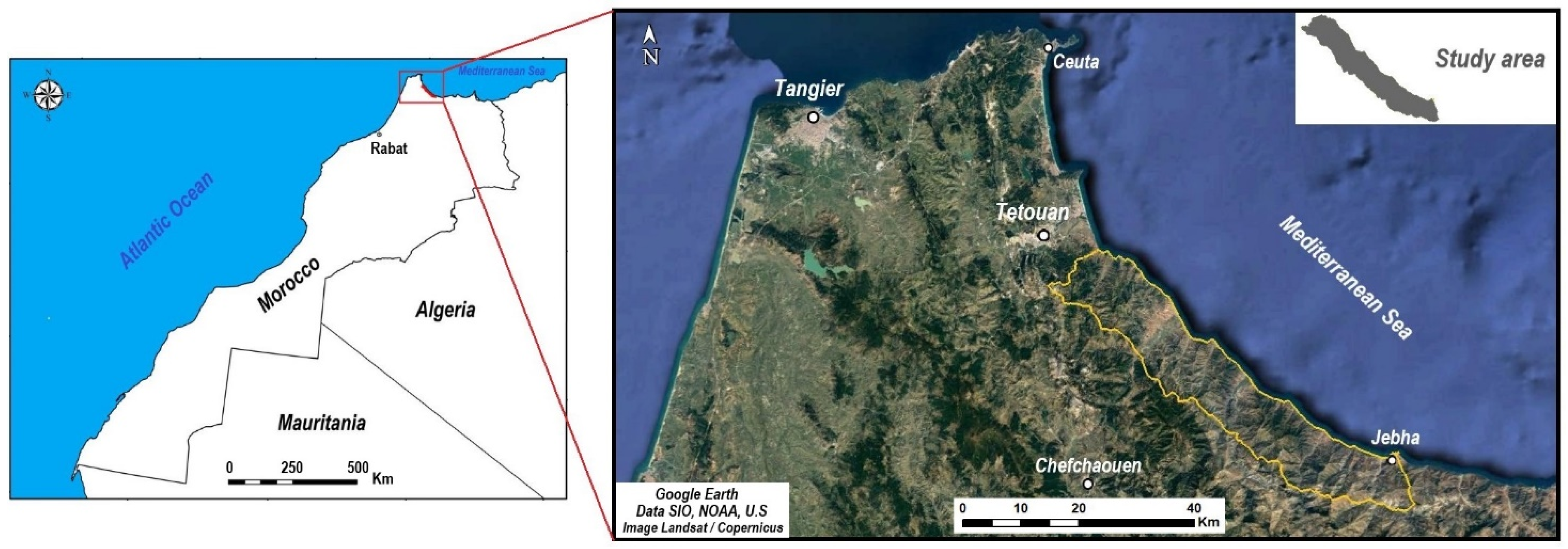

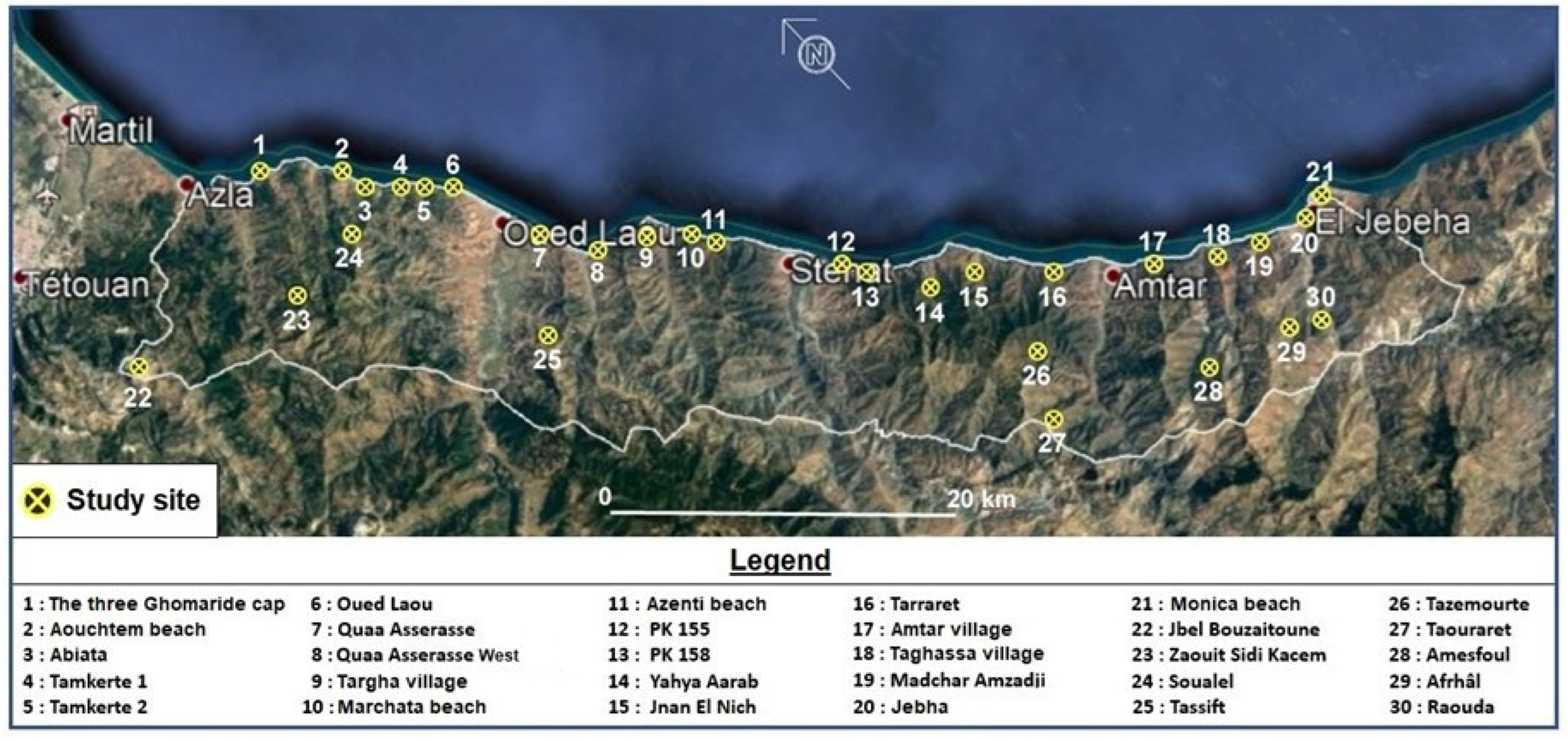

2. Studied Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Materials

3.2.1. Exploitation of the Inventory

3.2.2. Study Site and Input Data

4. Results and Discussion

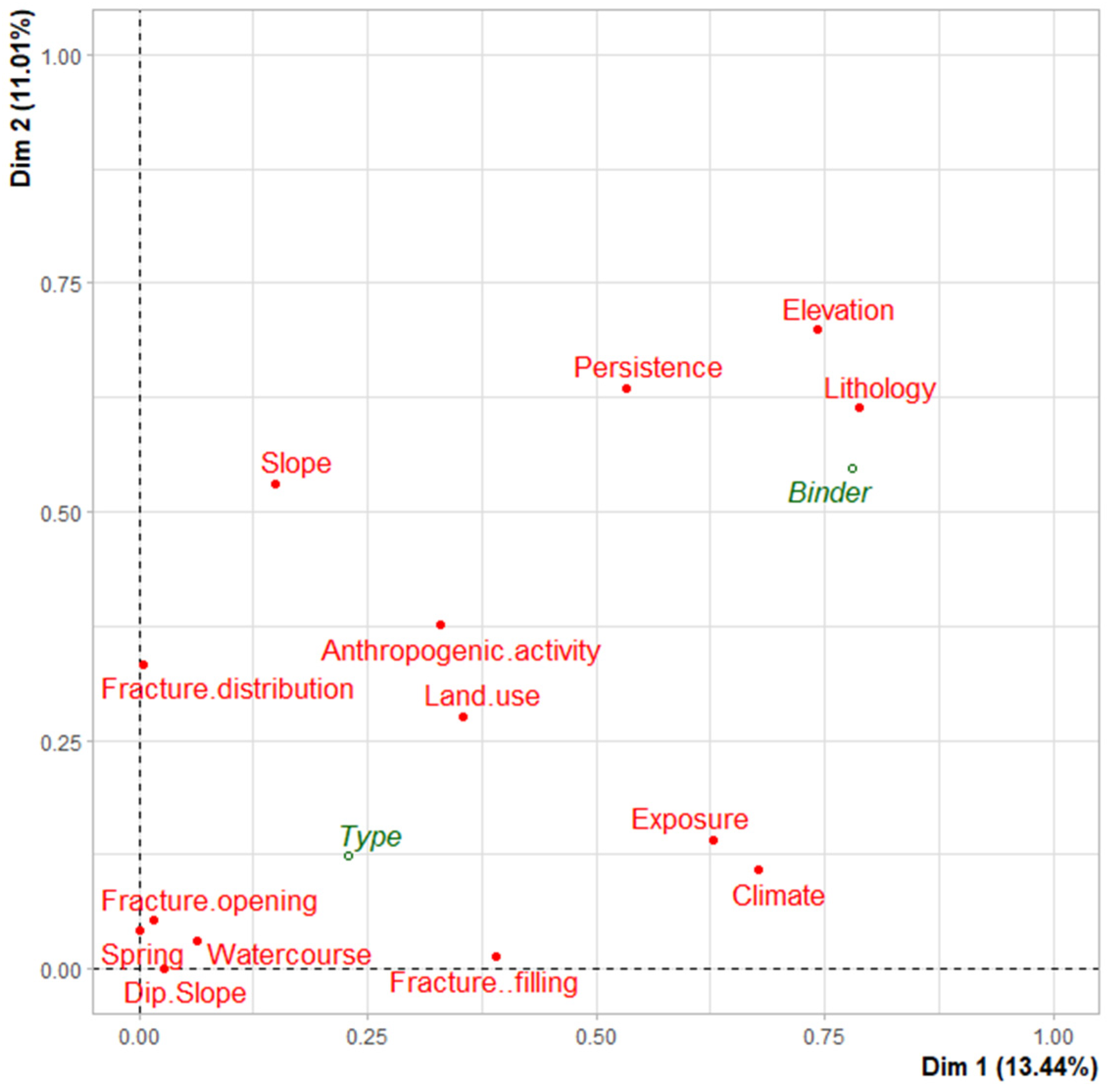

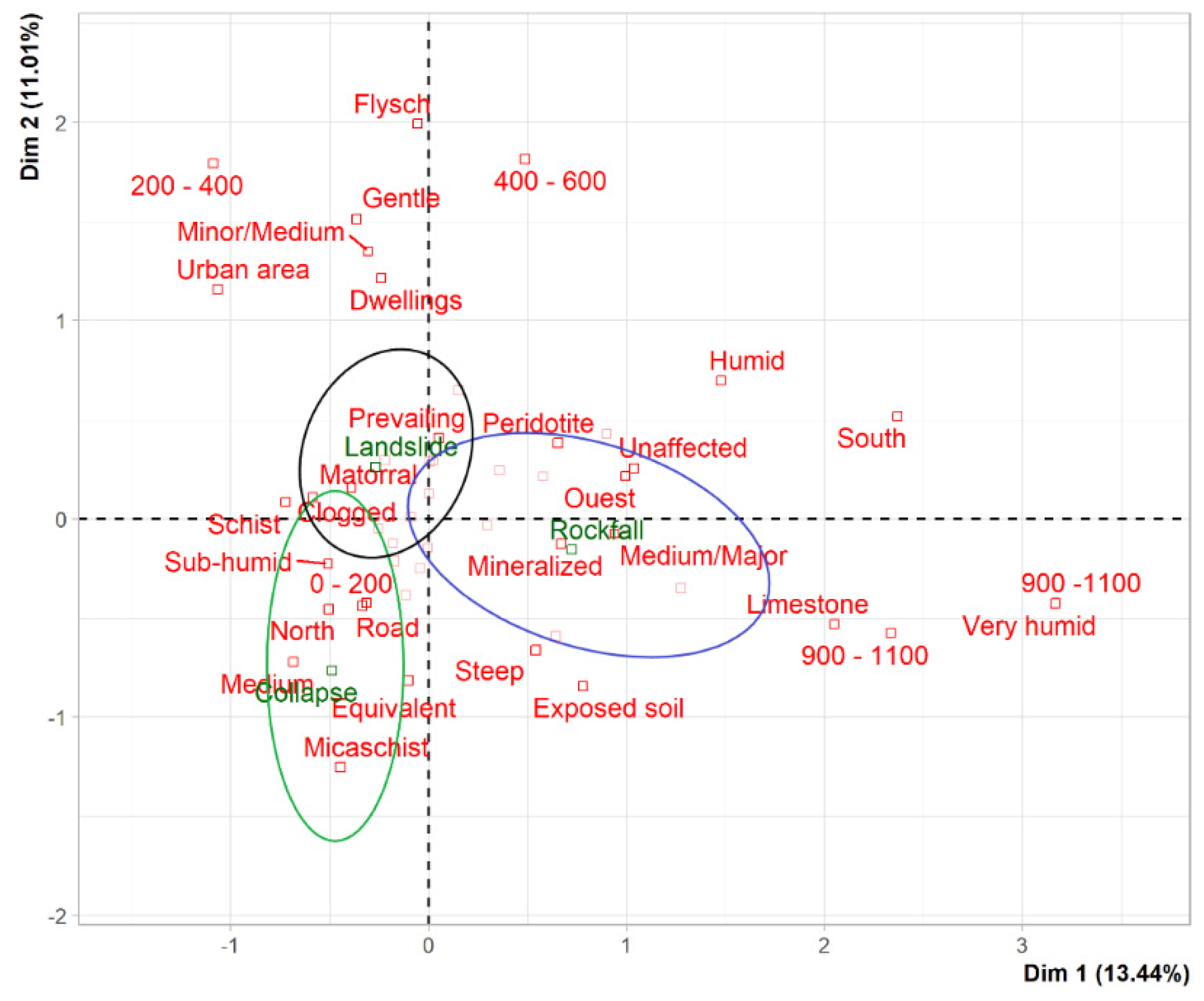

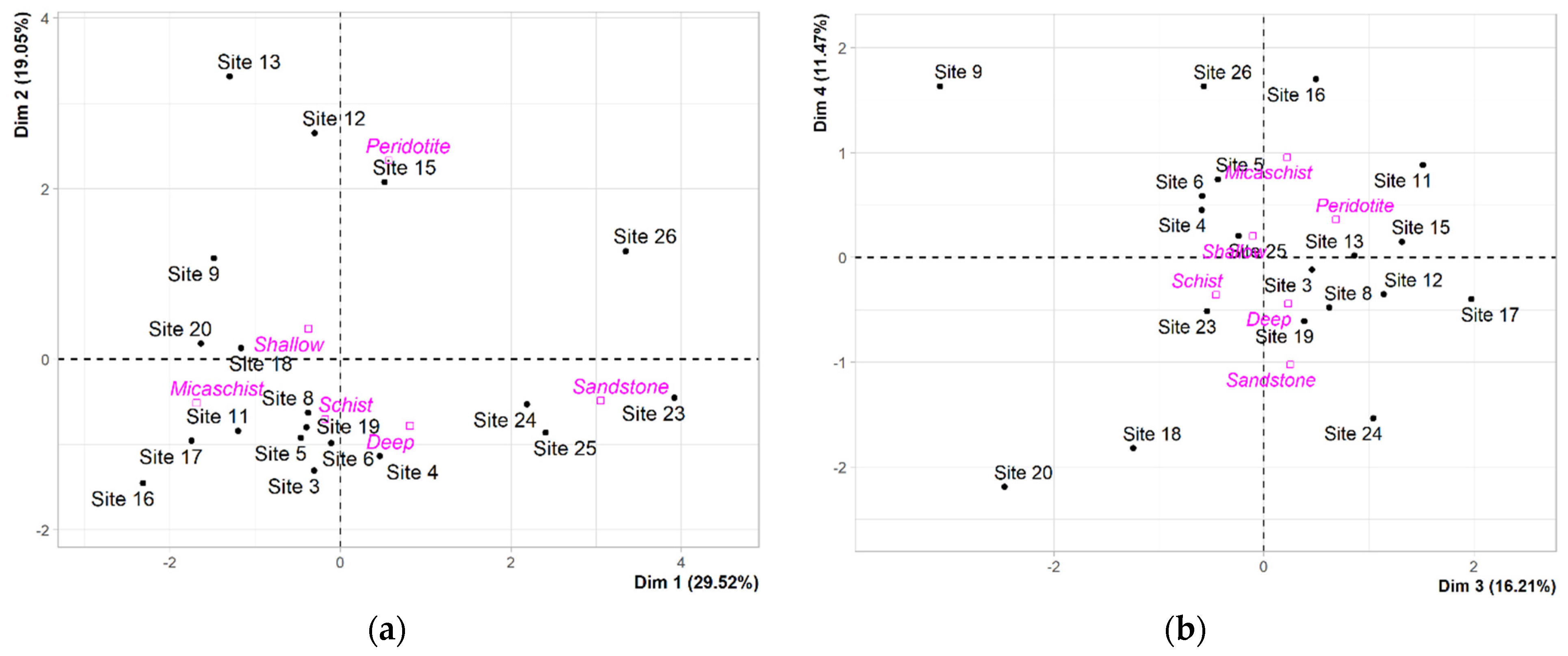

4.1. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

4.1.1. Choice of Factorial Design and Distribution of Inertia

4.1.2. Data Contribution to the Axes

4.1.3. Interpretation of Graphs

- Geological variables

- Geometric variables

- Hydrological variables

- Anthropogenic and land use variables

4.1.4. Analysis and Interpretation of Correlations

4.1.5. Focus on the Additional Variable “Type”

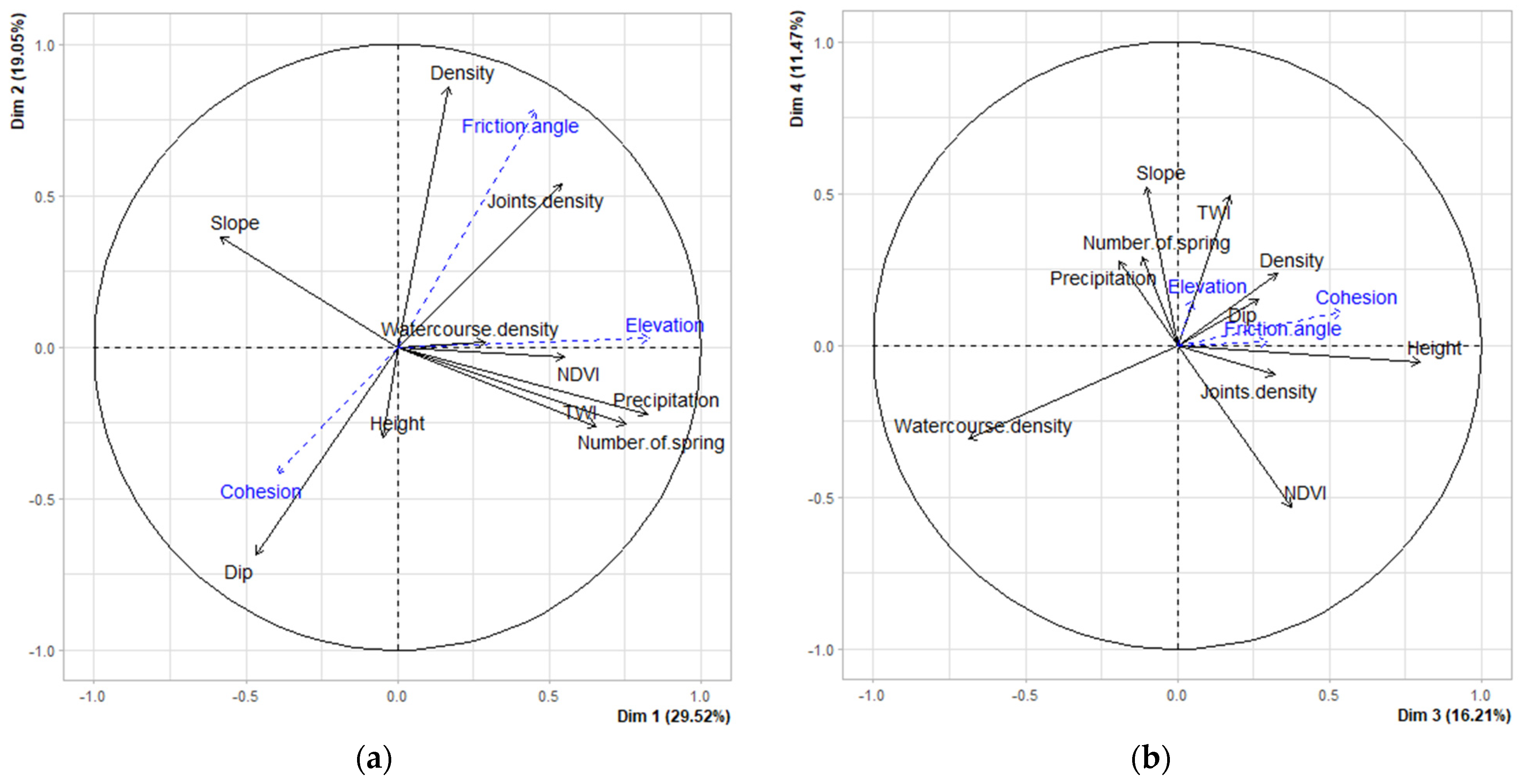

4.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)—Landslide Analysis

4.2.1. Choice of Factorial Design and Distribution of Inertia

4.2.2. Data Contribution to the Axes

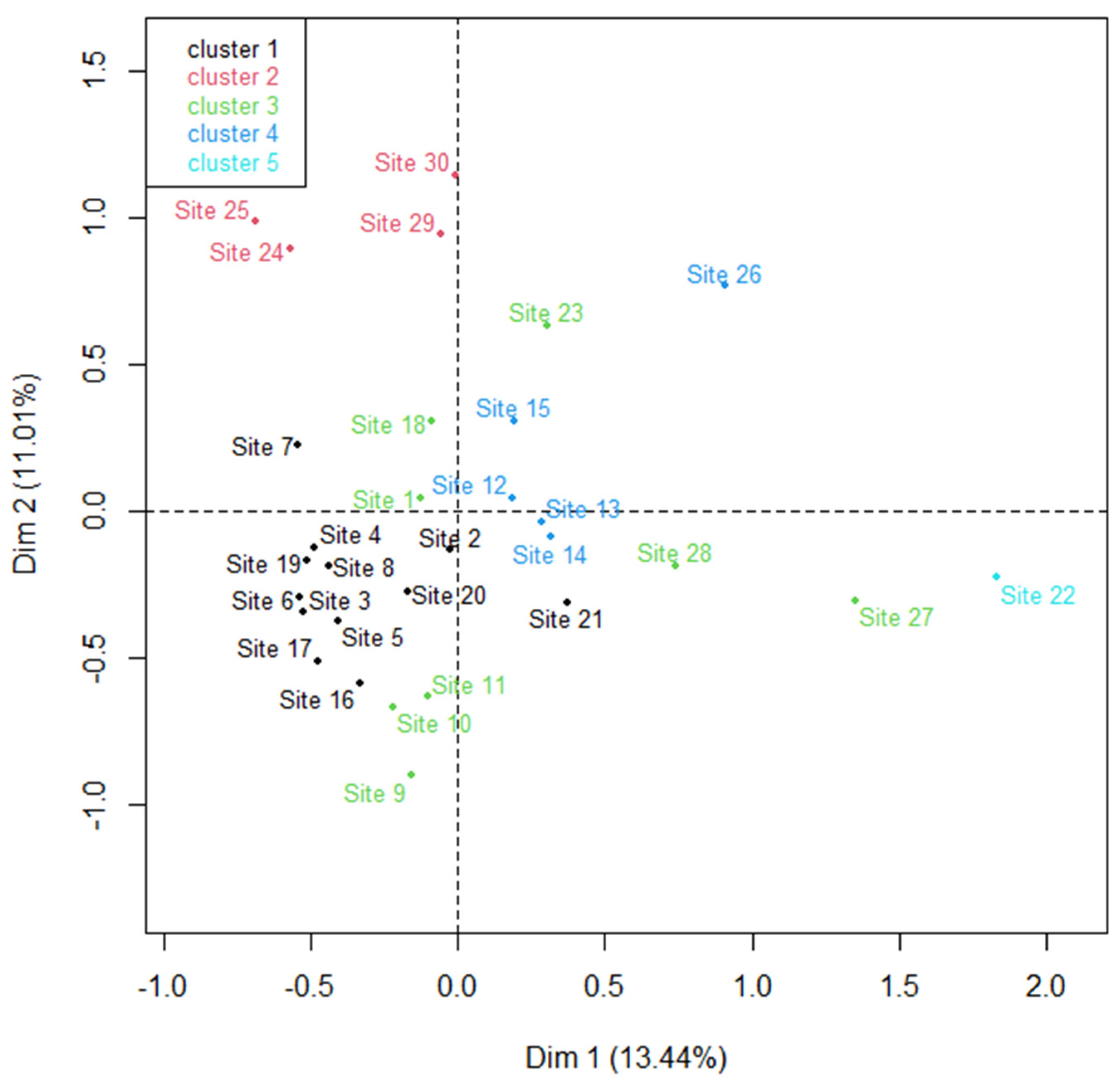

- Interpretation of the individuals’ graph

- Interpretation of the graphs of variables

4.2.3. Study of Proximities between Points

4.2.4. Analysis and Interpretation of Correlations

4.2.5. Interpretation of the Additional Qualitative Variable “Landslide Depth”

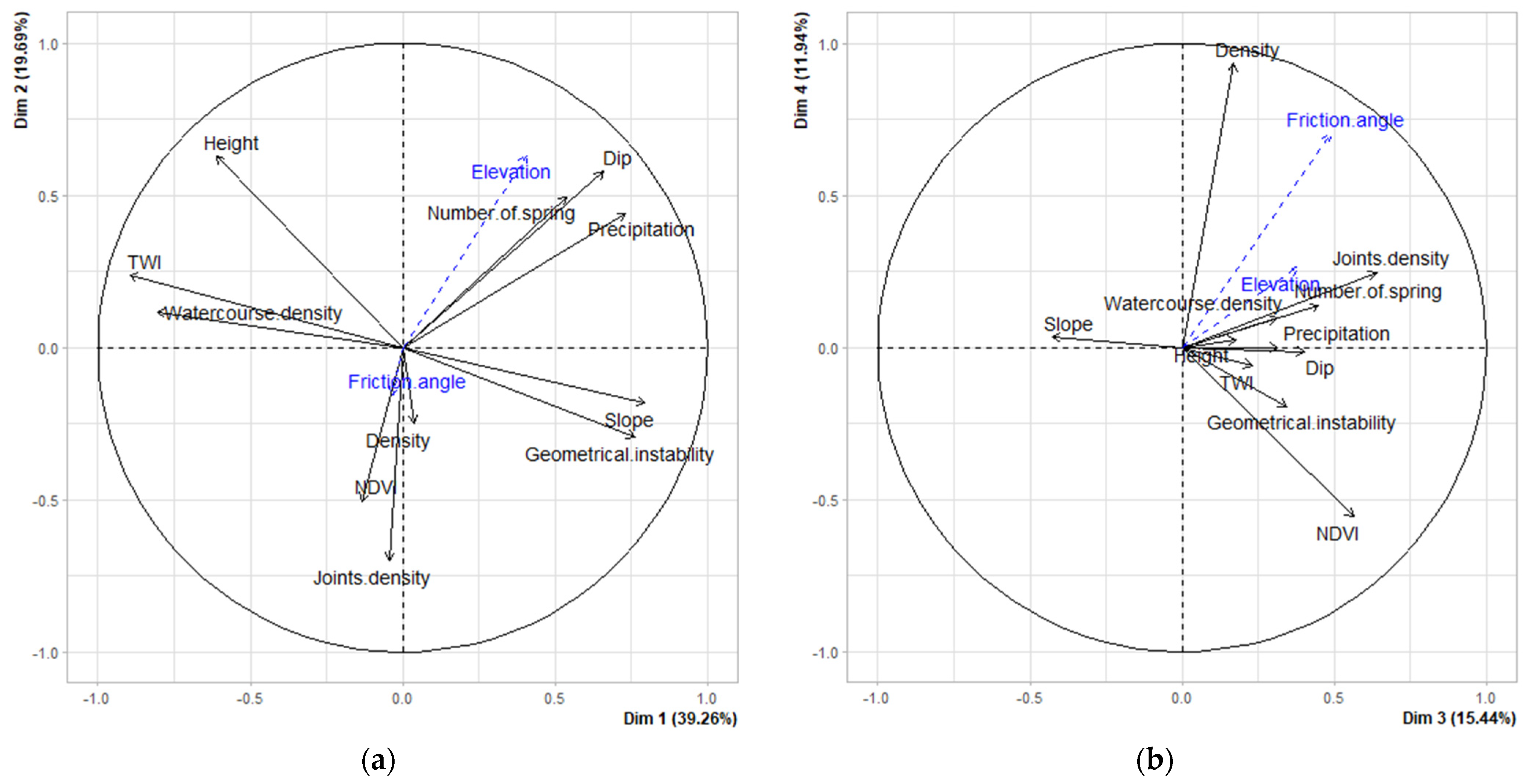

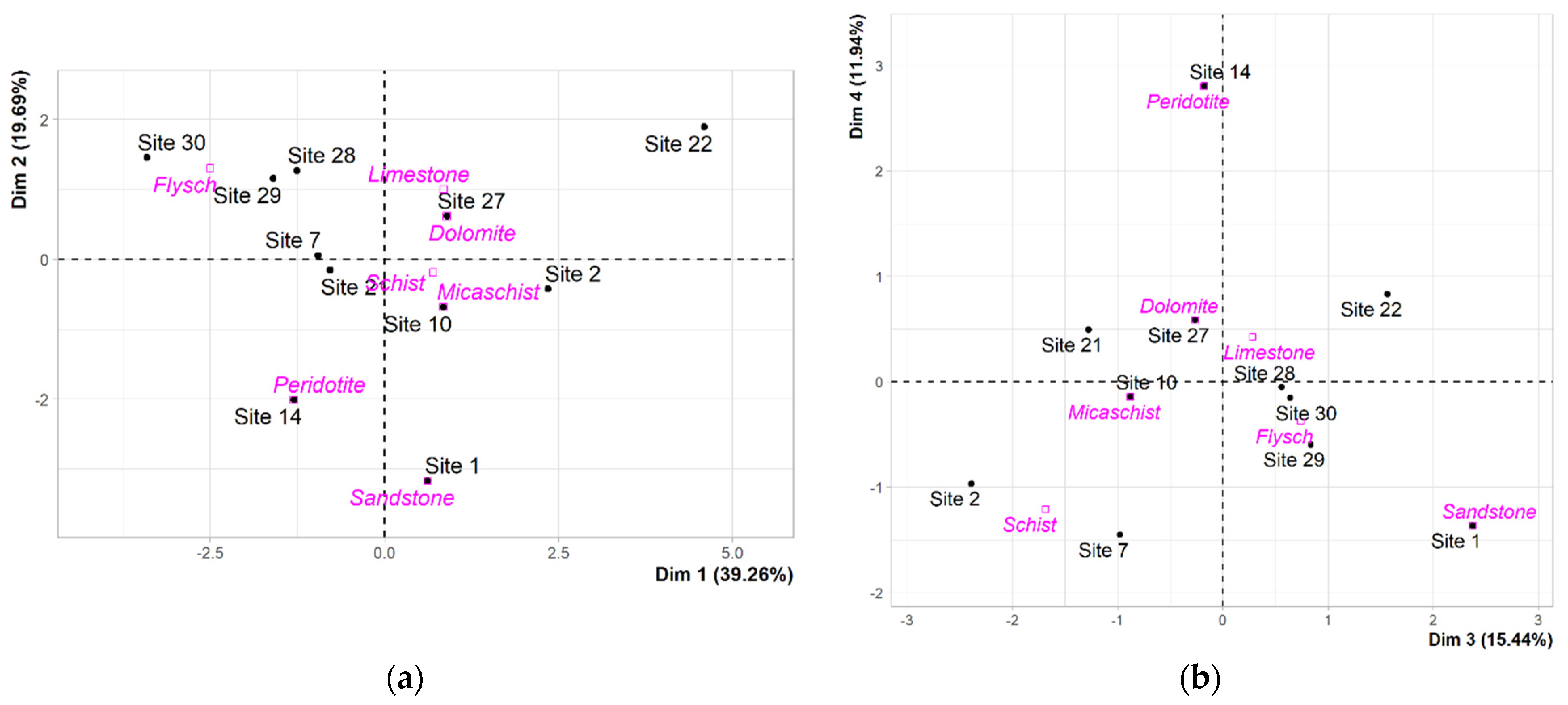

4.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)—Rockfall Analysis

4.3.1. Choice of Factorial Design and Distribution of Inertia

4.3.2. Data Contribution to the Axes

- Interpretation of the graph of variables

- Interpretation of the graph of individuals

4.3.3. Study of the Proximities between Points

4.3.4. Analysis and Interpretation of Correlations

4.3.5. Interpretation of the Additional Qualitative Variable “Lithology”

5. Discussion

5.1. MCA

5.2. PCA

5.2.1. Landslides

- In this group, all predisposing factors in the active dataset have the same level of influence. In other words, removing or changing the value of any of the variables can completely change an unstable terrain into a stable terrain or conversely, increase the instability. Lithologically, this group includes only shales and micaschists; this may indicate that the lithological nature of the terrain controls the values of the other variables modalities. It is important to note that in the case of metamorphic rocks, schistosity most likely plays an important role, even though it is not included in the dataset because it is very difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, it can represent a very important predisposition parameter by strongly increasing the joint density and fragmenting the rock.

- This group is represented by peridotites. It is differentiated by its high values of geomechanical parameters. In the study area, landslides are present in rocks with low to medium density except for the peridotites. Peridotites have the highest density in the area (3000 to 3200 kg/m3), and most instabilities correspond to landslides. Until further studies are undertaken, this group will be considered to be controlled by its geological parameters.

- This group is represented by the presence of springs, which constitutes a permanent predisposition factor and is the most influential factor for landslides. It should be noted that the presence of a spring does not necessarily indicate the presence of a landslide. Similarly, the presence of a landslide near a spring does not mean that the landslide is necessarily related to this spring, and this has been proven by the PCA.

- This group includes the majority of landslides encountered in the vicinity of an anthropogenic infrastructure (road, runway, structure, etc.). Man can intervene and modify certain natural parameters, in particular geomechanical parameters and the NDVI of the terrain, and thus increase the susceptibility of landslides. According to PCA, this group is controlled by NDVI, which has a negative value most of the time, thus decreasing the stability. Moreover, the negative value of NDVI becomes an indicator that the area where the landslide is located has been affected by anthropogenic interventions.

5.2.2. Rockfalls

5.3. Synthesis of Causative Factors

5.4. Reproductibility of the Methodoly

6. Conclusions

- The choice of factorial designs depends on the terminology of the study and of the objectives sought.

- For an analysis to be fair and complete, the dimensions chosen must be representative of the causative factors, and each factor must have a minimum contribution.

- For both methods (MCA and PCA), multiple correlation analysis highlighted the number of interrelationships for each factor.

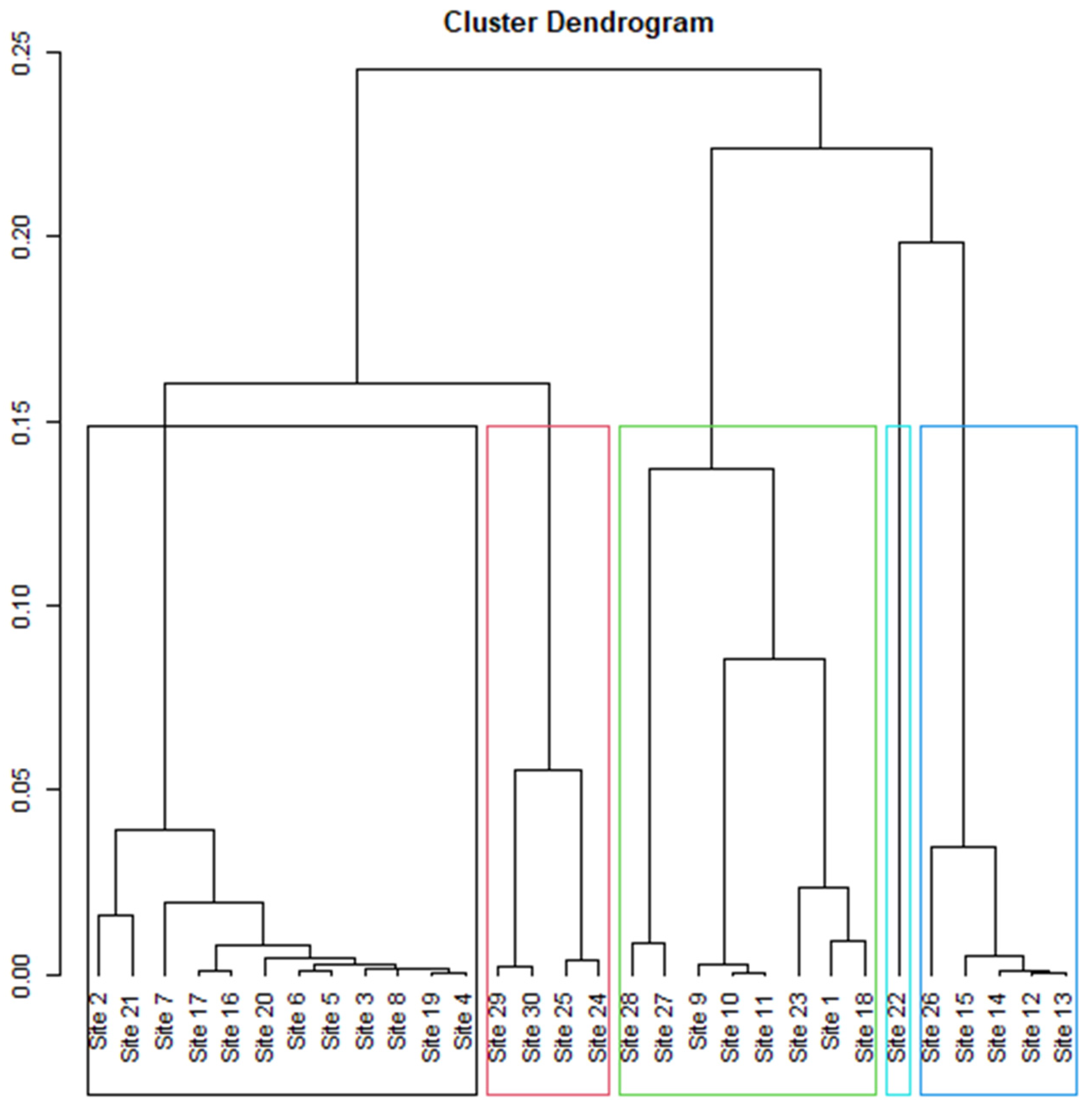

- In MCA, the classification of factors according to their order of influence can be performed through the observation of the number of correlations of each factor and through a hierarchical classification that groups the study sites into instability classes.

- In PCA, the assessment of influence degree causative factors depends on the correlations number analysis between variables, and even more on the belonging of the study sites to a specific group of variables.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Imput data for MCA and PCA

| Individual Variable | Type | Lithology | Binder | Persistence | Fracture Opening | Fracture Filling | Fracture Distrib. | Dip/ Slope | Slope | Elevation | Exposure | Water Source | Spring | Land Use | Anthropologic Activity | Climate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | C | Sd | Q | Min/Med | Jointed | Minz. | Prevail. | Out. | Steep | 0–200 | E | A | A | Matorral | Road | S H |

| Site 2 | R | S | Cl | Med/Maj | Open | Clogged | Equiv. | Out. | V steep | 0–200 | E | A | A | Forest | Unaffected | S H |

| Site 3 | L | S | Cl | Med | Open | Clogged | Equiv. | Ent. | Slight | 0–200 | N | A | P | Matorral | Road | S H |

| Site 4 | L | S | Cl | Med | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Out. | Slight | 0–200 | N | P | P | Matorral | Road | S H |

| Site 5 | L | S | Cl | Med | Open | Clogged | Equiv. | Out. | Steep | 0–200 | N | P | P | Matorral | Road | S H |

| Site 6 | L | S | Cl | Med | Open | Clogged | Equiv. | Out. | Slight | 0–200 | E | A | A | Matorral | Road | S H |

| Site 7 | R | S | Cl | Med | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Ent. | Slight | 0–200 | E | A | A | Urb area | Dwellings | S H |

| Site 8 | L | S | Cl | Med | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Ent. | Slight | 0–200 | N | P | A | Matorral | Road | S H |

| Site 9 | C | MS | Q-M | Med | Jointed | Minz. | Equiv. | Out. | Steep | 0–200 | N | A | A | Exposed | Road | S H |

| Site 10 | R | MS | Q-M | Med | Jointed | Minz. | Equiv. | Ent. | Steep | 0–200 | E | A | A | Matorral | Road | S H |

| Site 11 | L | MS | Q-Cl | Med | Jointed | Minz. | Prevail. | Out. | Steep | 0–200 | E | A | A | Exposed | Road | S H |

| Site 12 | L | P | None | Med/Maj | Open | Minz. | Prevail. | Out. | Slight | 0–200 | E | A | A | Forest | Road | S A |

| Site 13 | L | P | None | Med/Maj | Open | Minz. | Prevail. | Out. | Steep | 0–200 | E | A | A | Forest | Road | S A |

| Site 14 | R | P | None | Med/Maj | Open | Minz. | Prevail. | Out. | Steep | 0–200 | N | P | A | Forest | Road | S A |

| Site 15 | L | P | None | Med/Maj | Open | Minz. | Prevail. | Ent. | Slight | 0–200 | E | P | A | Matorral | Dwellings | S A |

| Site 16 | C | MS | Cl | Med | Open | Clogged | Equiv. | Out. | Slight | 0–200 | N | A | P | Exposed | Road | S A |

| Site 17 | L | MS | Cl | Med | Open | Clogged | Equiv. | Out. | Slight | 0–200 | N | A | A | Matorral | Road | S A |

| Site 18 | L | S | Cl | Min/Med | Jointed | Minz. | Prevail. | Out. | Gentle | 0–200 | W | P | A | Matorral | Road | Arid |

| Site 19 | C | S | Cl | Medium | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Out. | Slight | 0–200 | N | A | P | Matorral | Road | Arid |

| Site 20 | L | S | Cl | Med/Maj | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Out. | Slight | 0–200 | N | A | A | Exposed | Road | Arid |

| Site 21 | R | L | Ca | Med/Maj | Open/Jointed | Clogged | Prevail. | Out. | Steep | 0–200 | N | A | A | Matorral | Unaffected | Arid |

| Site 22 | R | L | Ca | Med/Maj | Open | Minz. | Prevail. | Ent. | Steep | 900–1100 | S | A | P | Exposed | Unaffected | V H |

| Site 23 | L | Sd | Q | Min/Med | Jointed | Minz. | Prevail. | Out. | Gentle | 600–800 | W | A | P | Matorral | Road | H |

| Site 24 | L | S | Cl | Min/Med | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Out. | Gentle | 200–400 | E | A | A | Matorral | Dwellings | S H |

| Site 25 | L | S | Cl | Min/Med | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Out. | Gentle | 200–400 | N | A | P | Urb area | Dwellings | S H |

| Site 26 | L | P | None | Med/Maj | Open | Minz. | Prevail. | Ent. | Slight | 400–600 | S | P | P | Forest | Dwellings | Humid |

| Site 27 | R | L | Ca | Med/Maj | Open | Minz. | Equiv. | Out. | Steep | 900–1100 | W | P | A | Exposed | Unaffected | Humid |

| Site 28 | R | D | Ca | Med/Maj | Open | Minz. | Equiv. | Out. | Slight | 600–800 | W | P | A | Exposed | Unaffected | S H |

| Site 29 | R | F | Cl-L | Min/Med | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Out. | Slight | 400–600 | E | A | P | Matorral | Unaffected | S A |

| Site 30 | L | F | Cl-L | Min/Med | Open | Clogged | Prevail. | Out. | Gentle | 400–600 | E | P | A | Matorral | Unaffected | S A |

| Individual | Landslide Depth | Lithology | Φ (°) | C (kPa) | Density (kg/m3) | Dip (°) | Joint Density (m−3) | Precipitation (mm/an) | Slope Angle (°) | Height (m) | Elevation (m) | Watercourse (m−2) | Nb of Springs | NDVI | TWI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 3 | Deep | Schist | 15 | 500 | 2300 | 20 | 2.5 | 600 | 50 | 200 | 150 | 0.765 | 1 | 0.1 | 5.78 |

| Site 4 | Shallow | Schist | 15 | 250 | 2300 | 20 | 3.5 | 600 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 0.765 | 2 | 0.1 | 6.5 |

| Site 5 | Shallow | Schist | 15 | 280 | 2300 | 25 | 3.5 | 600 | 55 | 100 | 250 | 0.584 | 1 | 0.06 | 6.5 |

| Site 6 | Deep | Schist | 15 | 135 | 2300 | 15 | 2.4 | 600 | 45 | 80 | 30 | 0.584 | 0 | 0.02 | 8.5 |

| Site 8 | Deep | Schist | 15 | 430 | 2300 | 15 | 7.66 | 600 | 45 | 200 | 150 | 0.765 | 0 | 0.02 | 5.78 |

| Site 9 | Shallow | Micaschist | 15 | 70 | 2500 | 10 | 7.28 | 600 | 65 | 25 | 90 | 1.98 | 0 | −0.25 | 5.78 |

| Site 11 | Shallow | Micaschist | 15 | 770 | 2500 | 40 | 7.28 | 600 | 60 | 250 | 160 | 0.765 | 0 | 0.02 | 6.5 |

| Site 12 | Shallow | Peridotite | 30 | 140 | 3200 | 0 | 13.5 | 400 | 50 | 120 | 150 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.07 | 5.2 |

| Site 13 | Shallow | Peridotite | 30 | 260 | 3200 | 0 | 13.5 | 400 | 65 | 120 | 150 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.07 | 3.5 |

| Site 15 | Shallow | Peridotite | 30 | 120 | 3200 | 0 | 13.5 | 400 | 45 | 150 | 200 | 0.765 | 0 | 0.03 | 8 |

| Site 16 | Shallow | Micaschist | 15 | 400 | 2500 | 65 | 7.24 | 400 | 50 | 170 | 170 | 0.584 | 1 | −0.25 | 5.78 |

| Site 17 | Shallow | Micaschist | 15 | 670 | 2500 | 45 | 7.24 | 400 | 50 | 250 | 220 | 0.584 | 0 | 0.05 | 5.2 |

| Site 18 | Shallow | Schist | 15 | 135 | 2300 | 15 | 7.24 | 400 | 40 | 70 | 175 | 1.355 | 0 | 0.01 | 3.5 |

| Site 19 | Deep | Schist | 15 | 320 | 2300 | 40 | 12.24 | 400 | 45 | 160 | 100 | 1.355 | 1 | 0.02 | 5.78 |

| Site 20 | Shallow | Schist | 15 | 250 | 2300 | 15 | 4 | 400 | 50 | 100 | 30 | 2.855 | 0 | 0.02 | 2.5 |

| Site 23 | Deep | Sandstone | 25 | 90 | 2500 | 10 | 16 | 900 | 32 | 120 | 700 | 1.98 | 2 | 0.12 | 8 |

| Site 24 | Deep | Sandstone | 25 | 200 | 2500 | 20 | 14.5 | 700 | 35 | 200 | 350 | 1.562 | 1 | 0.2 | 6.5 |

| Site 25 | Shallow | Schist | 15 | 180 | 2300 | 10 | 10.5 | 700 | 40 | 100 | 300 | 0.955 | 2 | 0.12 | 8.5 |

| Site 26 | Shallow | Peridotite | 30 | 250 | 3200 | 0 | 13.5 | 900 | 52 | 150 | 700 | 1.98 | 3 | 0.02 | 7.5 |

| Individual | Lithology | Φ (°) | Density (kg/m3) | Dip (°) | Joints Density (m−3) | Geometric Instability | Precipitation (mm/an) | Slope Angle (°) | Height (m) | Elevation (m) | Watercourse Density | Spring | NDVI | TWI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | Sandstone | 25 | 2500 | 25 | 18 | 5 | 600 | 60 | 12 | 55 | 0.765 | 0 | 0.2 | 3.5 |

| Site 2 | Schist | 15 | 2300 | 30 | 3.5 | 3 | 600 | 110 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 2 |

| Site 7 | Schist | 15 | 2300 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 600 | 50 | 40 | 80 | 0.584 | 0 | 0.08 | 5.2 |

| Site 10 | Micaschist | 15 | 2500 | 15 | 8.28 | 4 | 600 | 80 | 85 | 150 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.02 | 3.2 |

| Site 14 | Peridotite | 30 | 3200 | 0 | 13.5 | 1 | 400 | 65 | 40 | 90 | 1.355 | 0 | 0.02 | 4.6 |

| Site 21 | Limestone | 25 | 2600 | 20 | 7.5 | 0 | 400 | 60 | 100 | 100 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.02 | 3.5 |

| Site 22 | Limestone | 25 | 2700 | 80 | 7.66 | 5 | 1100 | 85 | 45 | 1100 | 0 | 2 | 0.01 | 2.2 |

| Site 27 | Dolomite | 25 | 2700 | 35 | 6.5 | 2 | 900 | 60 | 90 | 1050 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.02 | 3.2 |

| Site 28 | Limestone | 25 | 2600 | 40 | 7.22 | 0 | 700 | 45 | 200 | 700 | 0.765 | 0 | 0.08 | 4.6 |

| Site 29 | Flysch | 20 | 2400 | 25 | 7.22 | 1 | 500 | 50 | 165 | 450 | 1.355 | 1 | 0.08 | 5.78 |

| Site 30 | Flysch | 20 | 2400 | 25 | 7.22 | 1 | 500 | 40 | 175 | 200 | 2.855 | 0 | 0.02 | 7.5 |

References

- Petley, D. Global patterns of loss of life from landslides. Geology 2012, 40, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froude, M.J.; Petley, D. Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 2161–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, F.; Mondini, A.C.; Cardinali, M.; Fiorucci, F.; Santangelo, M.; Chang, K.T. Landslide inventory maps: New tools for an old problem. Earth Sci. Rev. 2012, 112, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capecchi, V.; Perna, M.; Crisci, A. Statistical modelling of rainfall-induced shallow landsliding using static predictors and numerical weather predictions: Preliminary results. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, F.; Ardizzone, F.; Cardinali, M.; Galli, M.; Reichenbach, P.; Rossi, M. Distribution of landslides in the Upper Tiber River basin, central Italy. Geomorphology 2008, 96, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Campina, B. Le Rôle des Facteurs Géologiques et Mécaniques dans le Déclenchement des Instabilités Gravitaires: Exemple de Deux Glissements de Terrain des Pyrénées Atlantique (Vallée d’Ossau et Vallée d’Aspe). Ph.D. Thesis, Planète et Univers, Université Bordeaux I, Bordeaux, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Feng, F.; Guo, Z.; Feng, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q.; Ma, H.; Li, Y. Integrating principal component analysis with statistically-based models for analysis of causal factors and landslide susceptibility mapping: A comparative study from the loess plateau area in Shanxi (China). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasc-Barbier, M.; Virely, D.; Guittard, J.; Merrien-Soukatchoff, V. Different approaches to fracturation of mable rock—The case study of the St Beat tunnel (French Pyrenees). In Proceedings of the International Society for Rock Mechanics, Liege, Belgium, 9–12 May 2006; pp. 619–623. [Google Scholar]

- Delonca, A.; Gunzburger, Y.; Verdel, T. Statistical correlation between meteorological and rockfall databases. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 1953–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebur, M.N.; Pradhan, B.; Tehrany, M.S. Optimization of landslide conditioning factors using very high-resolution airborne laser scanning (LiDAR) data at catchment scale. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 152, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Li, W. Risk factor detection and landslide susceptibility mapping using Geo-Detector and Random Forest Models: The 2018 Hokkaido eastern Iburi earthquake. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroi, E.; Favre, J.L.; Rezig, S. Cartographie de l’aléa mouvements de terrain par analyse statistique sous SIG. Rev. Fr. De Géotech. 2001, 95–96, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- El Fellah, B.; Mastere, M. The central Rif Mediterranean coast: Slope failures causative factors. Bull. De L’institut Sci. 2015, 37, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Andrieux, J. La structure du Rif central. Etude des relations entre la tectonique de compression et les nappes de glissement dans un tronçon de la chaîne alpine. Notes Et Mémoires Du Serv. Géologique Du Maroc 1971, 235, 1–450. [Google Scholar]

- Kornprobst, J. Contribution à l’étude pétrographique et structurale de la zone interne du Rif (Maroc septentrional). Notes Et Mémoires Du Serv. Géologique Du Maroc 1974, 256, 1–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chalouan, A.; Michard, A. The Alpine Rif Belt (Morocco): A case of mountain building in a subduction-subduction-transform fault triple junction. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2004, 16, 489–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michard, A.; Negro, F.; Saddiqi, O.; Bouybaouene, M.L.; Chalouan, A.; Montigny, R.; Goffé, B. Pressure–temperature–time constraints on the Maghrebide mountain building: Evidence from the Rif–Betic transect (Morocco, Spain), Algerian correlations, and geodynamic implications. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2006, 338, 92–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiri, A. Etude Pétro-Structurale des Péridotites de Béni Bousera et des Roches Crustales sus-Jacentes (Rif Interne, Maroc): Implications Géodynamiques. Ph.D. Thesis, Pétrologie Métamorphique et Structurale, Université Cadi Ayyad, Marrakech, Morocco, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tribak, H.; Gasc-Barbier, M.; El Garouani, A. A multi-temporal ground instabilities inventory between Tetouan and Jebha (Morocco): Mapping, description and analysis. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. under review.

- Husson, F.; Josse, J. Multiple Correspondence Analysis. In Visualization and Verbalization of Data, 1st ed.; Blasius, J., Greenacre, M., Eds.; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2014; 392p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrien, M. L’intérêt de l’analyse en composantes principales (ACP) pour la recherche en sciences sociales. Cah Des Amériques Lat. 2003, 43, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itasca. Available online: https://www.itasca.fr/en/software/flac-slope (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Gasc-Barbier, M.; Merrien-Soukatchoff, V.; Virely, D. The role of natural thermal cycles on a limestone cliff mechanical behavior. Eng. Geol. 2021, 293, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasc-Barbier, M.; Ballion, A.; Virely, D. Design of large cuttings in jointed rock. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2008, 67, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeken, J.; van Assen, M.A.L.M. An empirical Kaiser criterion. Psychol. Methods 2017, 22, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbacké Dia, C.A.K.; Sarr, A.G.R.J.; Kafom, A.; Diome, T.; Ngom, D.; Thiaw, C.; Ndiaye, S.; Sembene, M. Identification morphométrique despopulations de Tribolium castaneum Herbst (Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae) inféodées à trois céréales à WidouThiengoli. J. App. Biosci. 2017, 119, 11929–11942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baccini, A. Statistique Descriptive Multidimensionnelle (pour les nuls). Publications de l’Institut de Mathématiques de Toulouse 2010. Available online: https://math.univ-toulouse.fr/~baccini/zpedago/asdm.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Husson, F.; Lê, S.; Pagès, J. Analyse de Données Avec R; Presses Universitaires de Rennes: Rennes, France, 2009; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Type | Three types of ground movements were considered: Landslides (L): all varieties of landslides were considered except for mudflows Rockfalls (R): only rockfall larger than 10 m3 were considered Road slope collapse (C): mass movements generated in artificial slope |

| Lithology | Sd: sandstone, S: schist, MS: micaschist, P: peridotite, L: limestone, D: dolomite, F: flysh |

| Binder | Nature of the cement or matrix interposed between the lamination joints (Q: quartzitic, Cl: claystone, M: mica, Ca: calcite, L: limestone) |

| Fracture persistence | Minor: not exceeding the thickness of the bank and/or length < 1 m Medium: crossing several banks and/or 1 m < length < 10 m Major: 10 to 100 m long |

| Fracture filling | Mineralized (Minz.): minerals of one or more visible generations Clogged: diffuse and homogeneous filling |

| Fracture opening | Specifies whether the fractures are open or joined |

| Fracture distribution | Equi. (Equivalent system): homogeneous fracture network with a grid distribution Prev. (Prevailing system): heterogeneous fracture network with a random organization |

| Dip/Slope | Ent (Entering): layers are opposite to the slope Out (Outgoing): layers are in the same direction as the slope |

| Slope | Gentle: slope less than 45° Slight: slope between 45 and 55° Steep: slope between 55 and 90° Very steep: slope greater than 90° |

| Elevation | Represented in the analysis by classes to appear as qualitative data |

| Exposure | Exposure of the slopes according to cardinal points: N (north), S (south), E (east), W (west) |

| Watercourse | Presence: the ground movement is in intersection with one of the morphological components of a watercourse Absence: total absence of watercourses in the vicinity of the movement. |

| (Water) Spring | Presence: spring within 10 m of the center of the movement Absence: total absence of spring near the movement |

| Anthropogenic activity | Road: presence of a road within a maximum distance of 5 m Dwellings: presence of a dwelling beyond maximum distance of 20 m Unaffected: absence of anthropogenic factors in the vicinity of the movement |

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Φ (°) | Friction angle |

| C (kPa) | Cohesion |

| Density (kg/m3) | Density of the intact rock |

| Joint density | Density of mechanical discontinuities: corresponds to the number of mechanical discontinuities/m3. Estimated from the analysis of fracture families and stratification banks |

| Precipitation (mm/an) | Precipitation rates for the last 5 years |

| Height (m) | Height of the slope where the ground movement is located |

| Elevation (m) | Average elevation level where the lower part of the movement is located |

| Density of the hydrographic network | Correspond to the number of watercourses/m2. Calculated from a GIS analysis that classifies rivers into magnitude zones |

| NDVI | Normalized differential vegetation index |

| TWI | Topographic wetness index |

| Geometric instability | Number of geometric instabilities (dihedrals or plane slides) obtained with a typical stereographic stability analysis |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tribak, H.; Gasc-Barbier, M.; El Garouani, A. Assessment of Ground Instabilities’ Causative Factors Using Multivariate Statistical Analysis Methods: Case of the Coastal Region of Northwestern Rif, Morocco. Geosciences 2022, 12, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12100383

Tribak H, Gasc-Barbier M, El Garouani A. Assessment of Ground Instabilities’ Causative Factors Using Multivariate Statistical Analysis Methods: Case of the Coastal Region of Northwestern Rif, Morocco. Geosciences. 2022; 12(10):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12100383

Chicago/Turabian StyleTribak, Haytam, Muriel Gasc-Barbier, and Abdelkader El Garouani. 2022. "Assessment of Ground Instabilities’ Causative Factors Using Multivariate Statistical Analysis Methods: Case of the Coastal Region of Northwestern Rif, Morocco" Geosciences 12, no. 10: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12100383

APA StyleTribak, H., Gasc-Barbier, M., & El Garouani, A. (2022). Assessment of Ground Instabilities’ Causative Factors Using Multivariate Statistical Analysis Methods: Case of the Coastal Region of Northwestern Rif, Morocco. Geosciences, 12(10), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12100383