Identifying 3000-Year Old Human Interaction Spheres in Central Fiji through Lapita Ceramic Sand-Temper Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Lapita People in the Pacific Islands

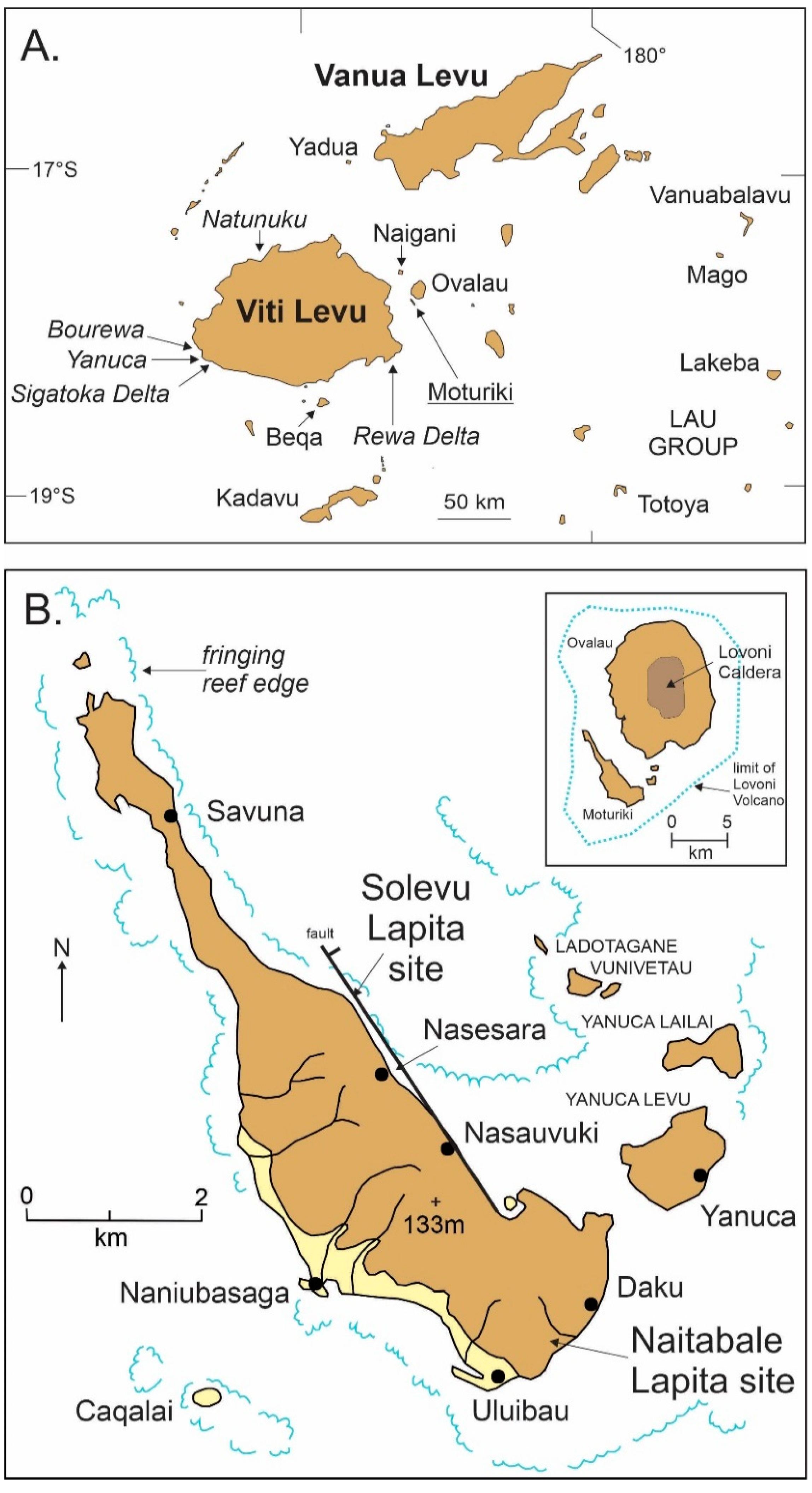

3. The Study Site: Geology and Environment

4. Excavations and Sampling

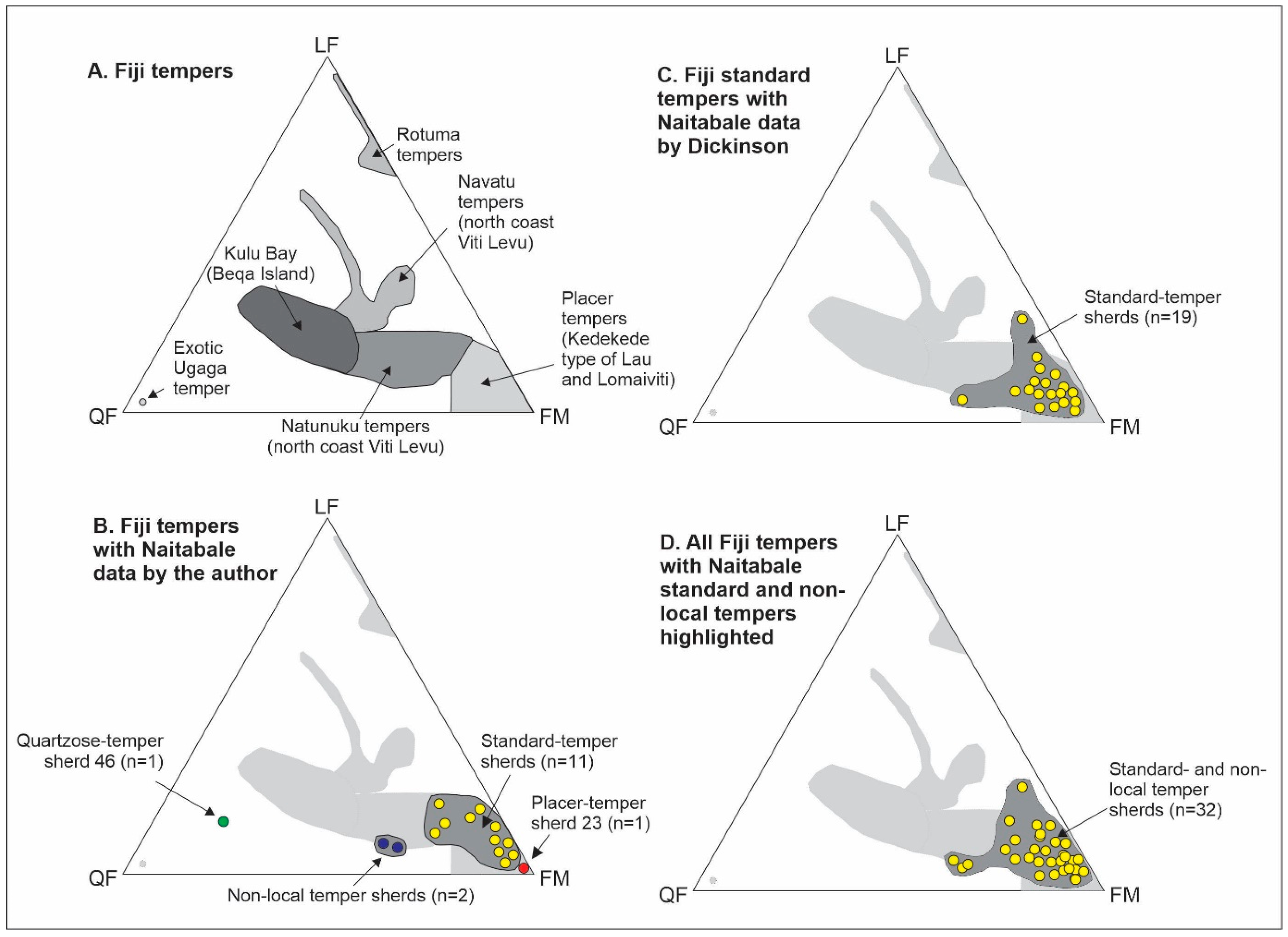

5. Analysis, Results and Interpretation

- The LF ratio—lithic fragments; for this purpose, the LF ratio is the percentage of volcanic lithic fragments in Table 1.

- The QF ratio—quartz and feldspar (plagioclase) mineral grains.

- The FM ratio—ferromagnesian silicate and oxide mineral grains (sum of percentages of clinopyroxene, hornblende and opaque iron oxides).

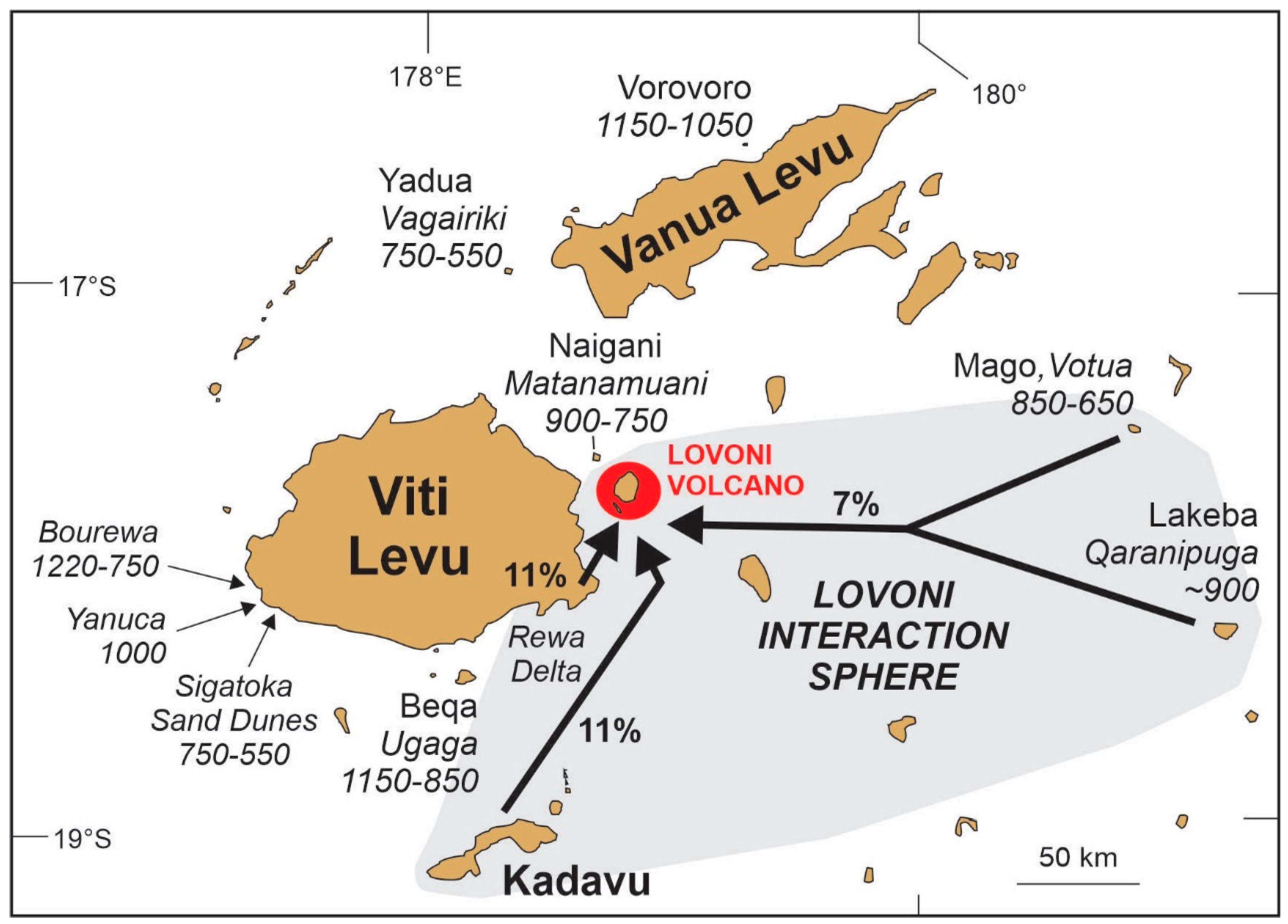

6. Discussion: The Lovoni Interaction Sphere in Fiji ~3000 Years Ago

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LeBlanc, K. A structural approach to ceramic design analysis: A pilot study of the “Eastern Lapita Province”. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R. Petrographic temper provinces of prehistoric pottery in Oceania. Rec. Aust. Mus. 1998, 50, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R. Temper Sands in Prehistoric Oceanian Pottery: Geotectonics, Sedimentology, Petrography, Provenance; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, W.R.; Shutler, R. Implications of petrographic temper analysis for Oceanian prehistory. J. World Prehistory 2000, 14, 203–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R.; Shutler, R. Probable Fijian origin of quartzose temper sands in prehistoric pottery from Tonga and Marquesas. Science 1974, 185, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhring, K.L.; Azemard, C.S.; Sheppard, P.J. Geochemical Characterization of Lapita Ceramics from the Western Solomon Islands by Means of Portable X-Ray Fluorescence and Scanning Electron Microscopy. J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 2015, 10, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R.; Takayama, J.; Snow, E.A.; Shutler, R. Sand temper of probable Fijian origin in prehistoric potsherds from Tuvalu. Antiquity 1990, 64, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavia, J.A.; Marsaglia, K.M.; Fitzpatrick, S.M. Petrography and Provenance of Sand Temper within Ceramic Sherds from Carriacou, Southern Grenadines, West Indies. Geoarchaeol. Int. J. 2013, 28, 450–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D.; Ishimura, T.; Dickinson, W.R.; Katayama, K.; Thomas, F.; Kumar, R.; Matararaba, S.; Davidson, J.; Worthy, T. The Lapita occupation at Naitabale, Moturiki Island, central Fiji. Asian Perspect. 2007, 46, 96–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, S.M.; Birks, L.; Birks, H.; Shaw, E. Lapita pottery style of Fiji and its associations. J. Polym. Soc. 1973, 82, 44–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kirch, P.V. The Lapita Peoples: Ancestors of the Oceanic World; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn, P.D. Echoes from a distance: Progress report on research into the Lapita occupation of the Rove Peninsula, southwest Viti Levu Island, Fiji. In Oceanic Explorations: Lapita and Western Pacific Settlement; Terra Australis 26; Bedford, S., Sand, C., Connaughton, S., Eds.; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2007; pp. 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn, P.D.; Kumar, R.; Matararaba, S.; Ishimura, T.; Seeto, J.; Rayawa, S.; Kuruyawa, S.; Nasila, A.; Oloni, B.; Ram, A.R.; et al. Early Lapita settlement site at Bourewa, southwest Viti Levu Island, Fiji. Archaeol. Ocean. 2004, 39, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D.; Petchey, F. Bayesian re-evaluation of Lapita settlement in Fiji: Radiocarbon analysis of the Lapita occupation at Bourewa and nearby sites on the Rove Peninsula, Viti Levu Island. J. Pac. Archaeol. 2013, 4, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, W.R.; Nunn, P.D. Petrography of sand tempers in Lapita potsherds from the Rove Peninsula, Southwest Viti Levu, Fiji. J. Pac. Archaeol. 2013, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, G.; Worthy, T.H.; Best, S.; Hawkins, S.; Carpenter, J.; Matararaba, S. Further investigations at the Naigani Lapita site (VL 21/5), Fiji: Excavation, radiocarbon dating and palaeofaunal extinction. J. Pac. Archaeol. 2011, 2, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn, P.D.; Matararaba, S.; Areki, F. A Lapita site on Ovalau Island, central Fiji Islands. Archaeol. N. Z. 2004, 47, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.R. Petrographic Character and Provenance of Lapita-Era Potsherds from Moturiki Island in Central Fiji: Implications for Early Human Ceramic Exchange; University of the South Pacific: Suva, Fiji, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, W.R. Petrography of Sand Tempers in Sherds from Naitabale. Moturiki, Fiji, 2004; Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson, F.I.E. Geology of the Lomaiviti and Moala Island Groups; Bulletin 2; Fiji Mineral Resources Division: Suva, Fiji, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ibbotson, P. The Geology of Ovalau, Moturiki and Naingani; Bulletin 9; Geological Survey of Fiji: Suva, Fiji, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, K.; Amesbury, J. Molluscs in a world of islands: The use of shellfish as a food resource in the tropical island Asia-Pacific region. Quat. Int. 2011, 239, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R. Petrography of Sand Temper in a Lapita Sherd from Moturiki. 2001; Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Anson, D. Lapita Pottery of the Bismarck Archipelago and Its Affinities; University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G. Post-Lapita Fiji: Cultural Transformation in the Mid-Sequence; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell, J.; Schechter, E. The meaning and importance of the Lapita face motif. Archaeol. Ocean. 2009, 44, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D.; Carson, M.T. Sea-level fall implicated in profound societal change about 2570 cal yr BP (620 BC) in western Pacific island groups. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2015, 2, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, D.V. Fijian polygenesis and the Melanesian/Polynesian divide. Curr. Anthropol. 2013, 54, 436–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, E.E.; Neff, H. Investigating compositional diversity among Fijian ceramics with laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS): Implications for interaction studies on geologically similar islands. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2006, 33, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, H. The Kula-Ring of Bronislaw Malinowski. A Simulation Model of the Co-Evolution of an Economic and Ceremonial Exchange System. Kolner Zeitschrift Soziologie Sozialpsychologie 2011, 63, 316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Rossitto, R. Fijian pottery in a changing world. J. Polym. Soc. 1992, 101, 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Best, S.B. Lakeba: The Prehistory of a Fijian Island; University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G. Ceramic assemblages from excavations on Viti Levu, Beqa-Ugaga and Mago islands. In The Early Prehistory of Fiji; Clark, G., Anderson, A., Eds.; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2009; pp. 259–306. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn, P.D.; Matararaba, S.; Ishimura, T.; Kumar, R.; Nakoro, E. Reconstructing the Lapita-era geography of northern Fiji: A newly-discovered Lapita site on Yadua Island and its implications. N. Z. J. Archaeol. 2005, 26, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Burley, D.V. Exploration as a strategic process in the Lapita settlement of Fiji: The implications of Vorovoro Island. J. Pac. Archaeol. 2012, 3, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G.; Anderson, A. (Eds.) Site chronology and a review of radiocarbon dates from Fiji. In The Early Prehistory of Fiji; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2009; pp. 153–182. [Google Scholar]

- Summerhayes, G. Lapita Interaction; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg, A.M.; Carroll, M.S. Your place or mine—The effect of place creation on environmental values and landscape meanings. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1995, 8, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter-Anderson, R.L.; Zan, Y. Demystifying the Sawei, a traditional interisland exchange system. ISLA J. Micrones Stud. 1996, 4, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, B. Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, W.R. Petrography and geologic provenance of sand tempers in prehistoric potsherds from Fiji and Vanuatu, South Pacific. Geoarchaeology 2001, 16, 275–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R.; Bedford, S.; Spriggs, M. Petrography of Temper Sands in 112 Reconstructed Lapita Pottery Vessels from Teouma (Efate): Archaeological implications and relations to other Vanuatu tempers. J. Pac. Archaeol. 2013, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Marsaglia, K.M.; Kramer, K.G.; David, B.; Skelly, R.J. Petrographic analyses of sand temper/inclusions in ceramics of Kikiniu, Kikori River and modern sand samples from the Gulf Province (Papua New Guinea). Archaeol. Ocean. 2016, 51, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebber, M.R.; Spurlock, L.B.; Fisch, M. A performance-based evaluation of chemically similar (carbonate) tempers from Late Prehistoric (AD 1200–1700) Ohio: Implications for human selection and production of ceramic technology. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sherd Number | Pit | Spit (cm) | Motif Class | Number of Grains Counted | % Plagioclase | % Clinopyroxene | % Hornblende | % Opaque Iron Oxides | % Volcanic Lithic Fragments | Pyribole Ratio | Temper Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | P3 | 140–150 | M436 | 87 | 8 (7) | 64 (56) | 16 (14) | 7 (6) | 5 (4) | 0.80 | standard |

| 23 | P3 | 140–150 | unclassed | 884 | 3 (29) | 2 (14) | 1 (12) | 85 (753) | 3 (24) | 0.67 | local variant of quartzose temper |

| 24 | P3 | 140–150 | - | 86 | 6 (5) | 69 (59) | 16 (14) | 3 (3) | 6 (5) | 0.81 | standard |

| 25 | P3 | 140–150 | M254 | 198 | 19 (37) | 44 (87) | 16 (31) | 9 (17) | 6 (11) | 0.73 | local variant of standard temper |

| 34 | P5 | 130–140 | unclassed | 125 | 14 (18) | 30 (37) | 34 (43) | 5 (6) | 17 (21) | 0.88 | standard |

| 46 | R1 | 100–110 | M378 | 259 | 53 (138) | 8 (20) | 6 (16) | 6 (16) | 6 (16) | 0.57 | quartzose |

| 56 | R2 | 60–70 | unclassed | 263 | 11 (28) | 63 (167) | 12 (32) | 5 (12) | 8 (20) | 0.84 | standard |

| 67 | R3 | 110–120 | M207 | 225 | 8 (17) | 63 (141) | 17 (38) | 12 (27) | 1 (2) | 0.79 | standard |

| 68 | T1 | 60–70 | M207 + M345? | 185 | 23 (42) | 35 (64) | 11 (20) | 14 (26) | 8 (14) | 0.76 | local variant of standard temper |

| 69 | T1 | 120–130 | M175 | 102 | 5 (5) | 59 (60) | 25 (25) | 4 (4) | 8 (8) | 0.70 | standard |

| 70 | T1 | 120–130 | M436? | 167 | 5 (8) | 76 (127) | 16 (26) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0.83 | standard |

| 71 | T1 | 130–140 | M154 | 29 | 7 (2) | 52 (15) | 28 (8) | 3 (1) | 10 (3) | 0.65 | standard |

| 72 | T1 | 130–140 | M260 | 97 | 4 (4) | 48 (47) | 34 (33) | 10 (10) | 3 (3) | 0.59 | standard |

| 73 | T1 | 130–140 | - | 120 | 3 (3) | 52 (62) | 35 (42) | 8 (9) | 3 (4) | 0.60 | standard |

| 74 | T1 | 140–150 | - | 93 | 2 (2) | 72 (67) | 18 (17) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 0.80 | standard |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, R.; Nunn, P.D.; Nakoro, E. Identifying 3000-Year Old Human Interaction Spheres in Central Fiji through Lapita Ceramic Sand-Temper Analyses. Geosciences 2021, 11, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11060238

Kumar R, Nunn PD, Nakoro E. Identifying 3000-Year Old Human Interaction Spheres in Central Fiji through Lapita Ceramic Sand-Temper Analyses. Geosciences. 2021; 11(6):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11060238

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Roselyn, Patrick D. Nunn, and Elia Nakoro. 2021. "Identifying 3000-Year Old Human Interaction Spheres in Central Fiji through Lapita Ceramic Sand-Temper Analyses" Geosciences 11, no. 6: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11060238

APA StyleKumar, R., Nunn, P. D., & Nakoro, E. (2021). Identifying 3000-Year Old Human Interaction Spheres in Central Fiji through Lapita Ceramic Sand-Temper Analyses. Geosciences, 11(6), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11060238