Pet Grief: Tools to Assess Owners’ Bereavement and Veterinary Communication Skills

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses, Participants, Material and Methods

- The Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure (CARE) [26] to assess the owners’ perception of the veterinarian’s relational empathy. It is a five-point Likert Scale ranging from poor to excellent, useful for measuring the quality of healthcare professionals’ relationships, based on empathy, capability to perceive the pet conditions and its feelings and to care for it [37]. The total scoring was obtained by adding all the items’ values (min 10, max 50). It has a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.9). The CARE has been extensively validated and it is widely used to measure the interpersonal quality of healthcare encounters in human medicine [38]. The permission to slightly change the wording of the questionnaire to fit into the veterinary context and translation of the questionnaire was provided by the author (2, May, 2017) (i.e., we changed: “How was the doctor at…” To “How was the veterinary at…”; “Being Positive … having a positive approach and a positive attitude; being honest but not negative about your problems” to “Being Positive … having a positive approach and a positive attitude; being honest but not negative about your dog’s/cat’s problems”).

- The Shared Decision-Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9) [27] is a nine-item instrument to assess the owners’ perceived level of involvement in shared decision-making related to the treatment and care of pets. It is a brief self-assessment instrument for measuring the process of shared decision-making in clinical encounters in human medicine, that is, the patients’ perceived level of involvement in decision-making related to their own treatment and care [27]. To use the questionnaire in the veterinary healthcare context, the wording of the SDM-Q-9 was slightly changed, focusing it on the pet’s condition and the owners. The instrument was developed according to the following definition: SDM is defined as an interactive process in which both parties (patient and physician) are equally and actively involved and share information to reach an agreement for which they are jointly responsible [39]. The SDM-Q-9 is unidimensional and shows high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.9) as well as high item discrimination, both indicating the high reliability of the instrument. The nine statements are rated on a six-point scale from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”. Scores of all items should be added (total score max 45, min 0). The permission to slightly change the wording of the questionnaire to fit into the veterinary context and translation of the questionnaire was provided by the authors (9, May, 2017) (i.e., we changed “My doctor made clear that a decision needs to be made” to “My veterinarian made clear that a decision needs to be made”; “My doctor told me that there are different options for treating my medical condition” to “My veterinarian told me that there are different options for treating the medical condition of my dog/cat”).

- To assess the pet grief distress, we utilized Pet Bereavement Questionnaire (PBQ) [24], a 16-item four-point Likert scale composed of three distinct factors: Grief (items: 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 12, 15), Anger (items: 1, 4, 11, 13, 14), and Guilt (items 6, 8, 9, 16). The Pet Bereavement Questionnaire (PBQ) was developed to fill the need for a brief, acceptable, well-validated instrument for use in studies of the psychological impact of losing a pet (Hunt and Padilla, 2006). The PBQ has been proven to have good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87), good factor structure, and good construct validity. The permission to translate the questionnaire into the Italian language was provided by the authors (13, July, 2012).

- To assess the owner’s intensity of regret, we utilized the Regret of Bereaved Family Members (RBFM) [25], a seven-item scale on a five-point self-reported Likert scale for bereaved family members measuring their self-evaluation on the decision to admit their loved ones to palliative care units. The wording of the RBFM was changed to re-focus it on the veterinary healthcare context. RBFM measures three aspects: overall degree of regret (total scoring), evaluation of decisional regret (items 1,2,3,4), and severity of intrusive thoughts about regret (items 5,6,7). The internal consistency was high for both “intrusive thoughts of regret” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85) and “decisional regret” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). The permission to slightly change the instructions of the questionnaire to adapt it to the veterinary context and to translate it into the Italian language was provided by the authors (5, May, 2017).

- The ontological representations of death were measured with the Testoni Death Representation Scale (TDRS; Testoni, Ancona, & Ronconi, 2015), which is a monofactorial scale composed by 6 items on a 5-point Likert scale. The TDRS explores the destiny of the personal identity of the responders between death as total annihilation and as a passage.

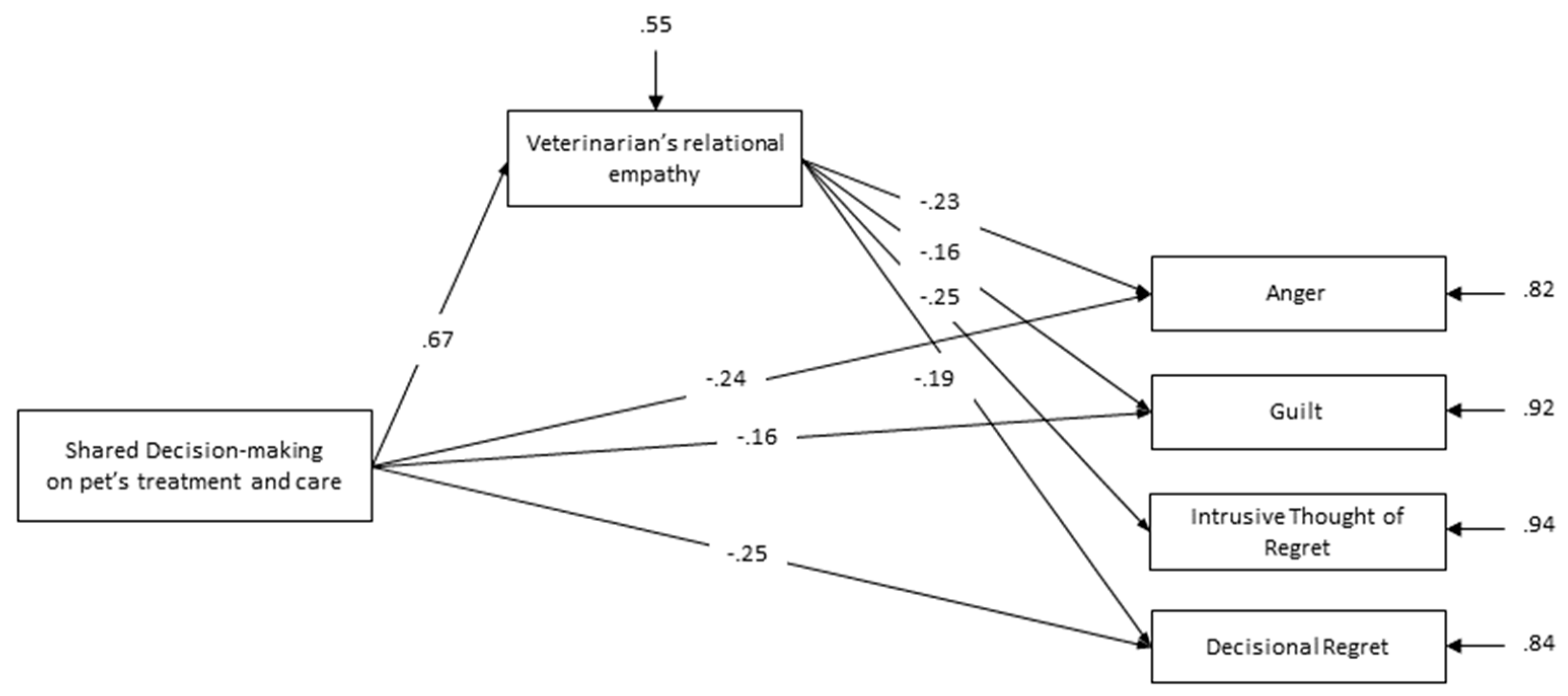

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure (CARE)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Appendix A.3. Pet Bereavement Questionnaire PBQ

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Appendix A.4. Regret of Bereaved Family Members (RBFM)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

References

- Zilcha-Mano, S.; Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on human–pet relationships: Conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. J. Res. Personal. 2011, 45, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, J.; Winchester, G. Bereavement following death of a pet. Br. J. Psychol. 1994, 85, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerwolls, M.K.; Labott, S.M. Adjustments to the death of a companion animal. Anthrozoös 1994, 7, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, N.P.; Orsini, L.; Gavish, R.; Packman, W. Role of attachment in response to pet loss. Death Stud. 2009, 33, 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doka, K.J. Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Hidden Sorrow; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Redmalm, D. Pet grief: When is non-human life grievable? Sociol. Rev. 2015, 63, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H. Death of a companion animal: Understanding human responses to bereavement. In The Psychology of the Human–Animal Bond. A Resource for Clinicians and Researchers; Blazina, C., Boyraz, G., Shenn-Miller, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Planchon, L.A.; Templer, D.I. The correlates of grief after death of pet. Anthrozoös 1996, 9, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchon, L.A.; Templer, D.I.; Stokes, S.; Keller, J. Death of a companion cat or dog and human bereavement: Psychosocial variables. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordaro, M. Pet loss and disenfranchised grief: Implications for mental health counseling practice. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2012, 34, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rémillard, L.W.; Meehan, M.P.; Kelton, D.F.; Coe, J.B. Exploring the grief experience among callers to a pet loss support hotline. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siess, S.; Marziliano, A.; Sarma, E.A.; Sikorski, L.E.; Moyer, A. Why Psychology Matters in Veterinary Medicine. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2015, 30, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoni, L. Family-present euthanasia: Protocols for planning and preparing clients for the death of a pet. In The Psychology of the Human–Animal Bond. A Resource for Clinicians and Researchers; Blazina, C., Boyraz, G., Shenn-Miller, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkin, B.S.; Knox, D. Pet loss: Issues and implications for the psychologist. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2003, 34, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.R.; Lagoni, L. End-of-life communication in veterinary medicine: Delivering bad news and euthanasia decision making. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2007, 37, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G.; Cooney, K.; Cox, S.; Downing, R.; Mitchener, K.; Shanan, A.; Soares, N.; Stevens, B.; Wynn, T. AAHA/IAAHPC End-of-Life Care Guidelines. Vet. Pract. Guidel. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2016, 52, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, E.S.; Crippa, F.; Calderari, T.; Prato-Previde, E. Empathy toward animals and people: The role of gender and length of service in a sample of Italian veterinarians. J. Vet. Behav. 2017, 17, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellehear, A.; Fook, J. Lassie come home: A study of ‘lost pet’notices. Omega J. Death Dying 1997, 34, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I. Psicologia del lutto e del morire: Dal lavoro clinico alla death education [The psychology of death and mourning: From clinical work to death education]. Psicoter. E Sci. Um. 2016, 50, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; De Cataldo, L. A special kind of grief. Cultural delegitimizations and representations of death in the case pet loss. Psicoter. E Sci. Um. 2017, 51, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; De Cataldo, L.; Ronconi, L.; Zamperini, A. Pet Loss and Representations of Death, Attachment, Depression, and Euthanasia. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euromonitor International, Pet Care in Italy. Available online: http://www.euromonitor.com/pet-care, (accessed on 3 January 2018).

- ASSALCO. Rapporto ASSALCO—Zoomark 2017. 2017. Available online: http://www.zoomark.it/media/zoomark/pressrelease/2017/Rapporto_Assalco-Zoomark_2017.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2018).

- Hunt, M.; Padilla, Y. Development of the pet bereavement questionnaire. Anthrozoös 2006, 19, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiozaki, M.; Hirai, K.; Dohke, R.; Morita, T.; Miyashita, M.; Sato, K.; Tsuneto, S.; Shima, Y.; Uchitomi, Y. Measuring the regret of bereaved family members regarding the decision to admit cancer patients to palliative care unit. Psycho-Oncology 2008, 17, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S.W.; Watt, G.C.M.; Maxwell, M.; Heaney, D.H. The development and preliminary validation of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure: An empathy-based consultation process measure. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriston, L.; Scholl, I.; Hölzel, L.; Simon, D.; Loh, A.; Härter, M. The 9-item Shared Decision-Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 80, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.R.; Adams, C.L.; Bonnett, B.N. What can veterinarians learn from studies of physician-patient communication about veterinarian-client-patient communication? J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 224, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.J.; Randall Curtis, J.; Tulsky, J.A. Achieving Goal-Concordant Care: A Conceptual Model Approach to Measuring Serious Illness Communication and Its Impact. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, K. Issues in Serious Veterinary Illness and End-of-Life Care. In Clinician’s Guide to Treating Companion Animal Issues. Addressing Human-Animal Interaction; Kogan, L., Blazina, C., Eds.; Academic Press Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 395–419. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.L.; Bonnett, B.N.; Meek, A.H. Predictors of owner response to companion animal death in 177 clients from 14 practices in Ontario. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 217, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.R. Four Core Communication Skills of Highly Effective Practitioners. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2006, 36, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D.K.; Miller, P.A.; Forbes-Thompson, S.A. Communication and end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Patient, family, and clinician outcomes. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2005, 28, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truog, R.D.; Meyer, E.C.; Burns, J.P. Toward interventions to improve end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, S373–S379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyajima, K.; Fujisawa, D.; Yoshimura, K.; Ito, M.; Nakajima, S.; Shirahase, J.; Mimura, M.; Miyashita, M. Association between quality of end-of-life care and possible complicated grief among bereaved family members. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, K.; Miksch, A.; Peters-Klimm, F.; Szecsenyi, J. Correlation between patient quality of life in palliative care and burden of their family caregivers: A prospective observational cohort study. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikker, A.P.; Mercer, S.W.; Cotton, P. Connecting, Assessing, Responding, Empowering (CARE): A universal approach to person-centred, empathic healthcare encounters. Educ. Prim. Care 2012, 23, 454–457. [Google Scholar]

- Bikker, A.P.; Fitzpatrick, B.; Murphy, D.; Mercer, S.W. Measuring empathic, person-centred communication in primary care nurses: Validity and reliability of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härter, M. Shared decision making—From the point of view of patients, physicians and health politics is set in place. Z. Arztl. Fortbild. Qual. 2004, 98, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, D.B.; Curran, P.J. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol. Methods 2004, 9, 466–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, L.J.; Croucamp, C.J.; Rees, C.S. What do people really think about grief counseling? Examining community attitudes. Death Stud. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, J.W. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner, 5th ed.; Springer Publishing Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N.; Yee-Melichar, D. Review of Principles and practice of grief counseling. Educ. Gerontol. 2015, 41, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.L.; Winokuer, H.R. Principles and Practice of Grief Counseling, 2nd ed.; Springer Publishing Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2015-45854-000&site=ehost-live (accessed on 30 January 2017).

- Burke, L.A.; Neimeyer, R.A. Prospective risk factors for complicated grief: A review of the empirical literature. In Complicated Grief: Scientific Foundations for Health Care Professionals; Stroebe, M., Schut, H., van den Bout, J., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 145–161. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2012-25312-011&site=ehost-live (accessed on 30 January 2017).

- Zhang, B.; El-Jawahri, A.; Prigerson, H.G. Update on Bereavement Research: Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Complicated Bereavement. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 1188–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazina, C.; Abrams, E. Working with men and their dogs: How context informs clinical practice when the bond is present in males’ lives. In Clinician’s Guide to Treating Companion Animal Issues: Addressing Human-Animal Interaction; Kogan, L., Blazina, C., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 223–252. [Google Scholar]

| Questionnaire | N | Factors | Chi-square | df | p | CFI 5 | TLI 6 | RMSEA [90% CI] 7 | WRMR 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARE 1 | 343 | 1 | 5.022 | 35 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.000 [0.000–0.000] | 0.302 |

| SDM 2 | 316 | 1 | 52.914 | 27 | 0.002 | 0.994 | 0.992 | 0.055 [0.033–0.077] | 1.084 |

| PBQ 3 | 327 | 3 | 281.02 | 101 | <0.001 | 0.953 | 0.944 | 0.074 [0.064–0.084] | 1.437 |

| RBFM 4 | 338 | 2 | 17.852 | 13 | 0.163 | 0.995 | 0.992 | 0.033 [0.000–0.068] | 0.798 |

| Variables | Range | M | SD | alpha | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CARE 1 Total score | 10–50 | 38.10 | 12.52 | 0.98 | |||||||||

| 2. SDM 2 Total score | 0–45 | 29.40 | 13.55 | 0.94 | 0.67 *** | ||||||||

| 3. PBQ 3 Grief | 0–21 | 14.66 | 4.93 | 0.87 | 0.01 | -0.03 | |||||||

| 4. PBQ 3 Anger | 0–15 | 3.52 | 3.10 | 0.60 | −0.38 *** | −0.39 *** | 0.49 *** | ||||||

| 5. PBQ 3 Guilt | 0-12 | 4.68 | 3.63 | 0.75 | −0.25 *** | −0.27 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.57 *** | |||||

| 6. PBQ 3 Total score | 0–48 | 22.87 | 9.43 | 0.86 | −0.21 *** | −0.25 *** | 0.84 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.78 *** | ||||

| 7 RBFM 4 Intrusive Thoughts of Regrets | 3–5 | 5.70 | 3.24 | 0.77 | −0.22 *** | −0.17 ** | 0.29 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.49 *** | |||

| 8. RBFM 4 Decisional Regrets | 4–20 | 7.95 | 4.48 | 0.86 | −0.34 *** | −0.38 *** | 0.07 | 0.41 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.50 *** | ||

| 9. RBFM 4 Total score | 7–35 | 13.64 | 6.71 | 0.85 | −0.33 *** | −0.33 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.82 *** | 0.91 *** | |

| 10. TDRS 5 Total score | 6–30 | 18.01 | 6.81 | 0.83 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.002 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.03 |

| Participant’s and Pet’s Characteristics | CARE 1 Total | SDM 2 Total | PBQ 3 Grief | PBQ 3 Anger | PBQ 3 Guilt | PBQ 3 Total | RBFM 4 Intrusive Thoughts of Regrets | RBFM 4 Decisional Regrets | RBFM 4 Total | TDRS 5 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants’ characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age (year) | 0.20 *** | 0.17 ** | −0.03 | −0.17 ** | −0.26 *** | −0.17 ** | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.05 |

| Gender a | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.19 *** | −0.12 * | −0.08 | −0.17 ** | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.05 |

| Educational level b | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.15 ** | −0.11 * | −0.08 | −0.15 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.19 *** | 0.00 |

| Work c | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.05 | −0.18 ** | −0.24 *** | −0.18 ** | −0.24 *** | −0.16 ** | −0.22 *** | 0.01 |

| Children d | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.17 ** | −0.13 * | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Live alone d | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.10 | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.10 |

| Pets’ characteristics | ||||||||||

| Animal species e | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Time from pet’s death (year) | −0.14 ** | −0.13 * | −0.25 *** | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.11 * | −0.18 ** | 0.09 | −0.03 | −0.12 * |

| Pet’s age at death (year) | 0.19 *** | 0.23 *** | −0.05 | −0.18 ** | −0.19 *** | −0.16 ** | −0.10 | −0.25 *** | −0.21 *** | 0.02 |

| Pet’s Ownership duration (year) | 0.16 ** | 0.19 *** | −0.01 | −0.18 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.13 * | −0.11 | −0.17 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.02 |

| Pet’s euthanasia d | 0.20 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.05 | −0.13 * | −0.19 *** | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.31 *** | −0.24 *** | 0.04 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Testoni, I.; De Cataldo, L.; Ronconi, L.; Colombo, E.S.; Stefanini, C.; Dal Zotto, B.; Zamperini, A. Pet Grief: Tools to Assess Owners’ Bereavement and Veterinary Communication Skills. Animals 2019, 9, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9020067

Testoni I, De Cataldo L, Ronconi L, Colombo ES, Stefanini C, Dal Zotto B, Zamperini A. Pet Grief: Tools to Assess Owners’ Bereavement and Veterinary Communication Skills. Animals. 2019; 9(2):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9020067

Chicago/Turabian StyleTestoni, Ines, Loriana De Cataldo, Lucia Ronconi, Elisa Silvia Colombo, Cinzia Stefanini, Barbara Dal Zotto, and Adriano Zamperini. 2019. "Pet Grief: Tools to Assess Owners’ Bereavement and Veterinary Communication Skills" Animals 9, no. 2: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9020067

APA StyleTestoni, I., De Cataldo, L., Ronconi, L., Colombo, E. S., Stefanini, C., Dal Zotto, B., & Zamperini, A. (2019). Pet Grief: Tools to Assess Owners’ Bereavement and Veterinary Communication Skills. Animals, 9(2), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9020067