1. Introduction

Thirty percent of American households have a pet cat [

1], and 15% of cat owners lose their pet at least once in a 5-year period [

2]. Many of these animals are not reunited with their owner, despite the owner desiring them back. A common outcome for a proportion of missing cats is to be taken into a shelter or municipal animal control facility. Many are ultimately euthanized if not reclaimed after a standard holding period that varies among shelters but is usually between 3 to 5 business days [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Of stray animals entering shelters in USA and Australia, reported reclaim percentages for cats are typically 2–4% compared to reclaim percentages for dogs which usually range from 26–40%, but can be as high as 90% [

6,

7,

8]. Cats are 13 times more likely to return to owners by means other than a visit to a shelter [

9]. For example, reunification may occur directly via the general public if the cat has identification such as an ID tag, or as a result of signage (e.g., lost and found posters). Alternatively, local neighborhood searches and owner-initiated trapping may be successful [

2,

10].

However, there is little published information to inform searches for lost cats, particularly regarding the likely location of the pet and effective search methods. Current literature informs on different methods used to find lost pets [

10], but the authors could find no peer-reviewed studies reporting the efficacy of methods used for finding missing cats, the most common locations missing cats were found, and the distance that lost cats travelled from where they went missing. This information is important so searches for lost pets are more effective at reuniting cats with their owners, therefore reducing euthanasia of unclaimed cats in shelters and municipal facilities.

The aim of the current study is to address gaps in the literature by reporting search methods used to find missing cats, methods most often associated with locating missing cats, and the location and distance travelled by missing cats that were found. It is anticipated that this information would assist in improving recovery percentages for lost cats.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective case series of owned cats that had become missing was conducted with cases (episodes of cats becoming lost, hereafter referred to as ‘cats’ or ‘missing cats’) recruited using a convenience sample, including snowball sampling. The study was approved by The University of Queensland’s (UQ) Human Ethics Committee (approval number 2016000737). The questionnaire format and content was formulated by a team consisting of a 5th year research elective student and staff within The University of Queensland’s School of Veterinary Science and members of Missing Pet Partnership (MPP), a not-for-profit organization in the United States involved in reuniting lost companion animals with their owners.

This study was conducted from June through to August 2016 via an online questionnaire, using commercial survey software (SurveyMonkey®, San Mateo, CA, USA), which was promoted by MPP. Promotional methods used were primarily through social media, word-of-mouth, and on the organization’s own website. Potential respondents were told that the questionnaire was to be completed by people over 18 years of age. Each completed questionnaire collected data for one cat that went missing once (i.e., for one case). If the respondent had multiple cats that went missing, they could complete the questionnaire separately for each cat. If the same cat had gone missing multiple times, the respondent could complete the questionnaire separately for each episode of their cat going missing.

Question formats used a combination of multi-choice answers, free-text answers as well as rating scales for questions that were more qualitative/emotive (e.g., describing the cat’s personality type). The questionnaire consisted of 47 questions relating to the following:

Signalment and basic history of lost cat—age, neuter status, duration of pet ownership, where it was obtained from, possession of any type of identification, experience with the environment outside, where it lived, personality type, degree of human-pet bond.

Circumstances in which it went missing—age at time it went missing, number of people home at time it went missing, how long it was missing for, approximate time when it went missing, where did it go missing from, number of hiding places around where it went missing;

Search methods used to locate the cat—how long was the search for, if cat was still being searched for, search methods used to locate the cat split into five broad categories of ‘physical search’, ‘placing an advert’, ‘contacting professional help’, ‘trap techniques’, ‘recovered via identification device’, ‘waiting’, in which each had sub-headings with more specific options and search methods that the participant thought was most effective;

Circumstances in which the cat was found (if applicable)—whether the cat was found or not, condition and behavior of the cat when found, where the cat was found, how far the cat was found from where it went missing.

Respondents were also asked to rank their cat for each of four cat personality traits consisting of curious/clown cat, aloofness, cautiousness and timidity/fearfulness [

11] on scale from 1 to 5 where 1 indicated ‘not at all’ and 5 indicated ‘perfectly describes my cat’s personality’.

The questionnaire was pilot tested by several UQ and MPP colleagues for clarity one month before launching, and it was subsequently modified. Responses were accepted from anywhere in the world.

Statistical analyses were completed using Stata (version 14, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Each cat’s possible outcomes were: found alive, found dead, and not found by the time the respondent completed the questionnaire. Outcomes were allocated to cats based on an algorithm that used responses to four study questions (

Table 1). Times from going missing to being found were as provided by respondents; for cats not found, time intervals were right-censored at the time the respondent completed the questionnaire using their reported time since the cat went missing. Cats whose times were not provided were excluded from analyses of time to being found alive (i.e., cats found, but time missing was not provided; and cats not found, and time since cat went missing was not provided). Cats whose times ended on the same day as they went missing were allocated a time of 0.5 day. Cumulative incidences of being found alive by time from when the cat went missing were then calculated using competing risks survival analyses, where being found dead was the competing event, using Stata’s-stcompet-command. These cumulative incidences described the probability that an individual cat would be found alive by time since the cat went missing. Cumulative incidence values are always on or between 0 and 1 (100%). Ninety-five percent point-wise confidence intervals were calculated using formula 4 described by Choudhury [

12]. Potential determinants of being found alive were assessed using competing risks regression, using Stata’s-stcrreg-command. These used the method of Fine and Gray [

13] and modeled the sub-hazard of being found alive, calculated such that cats that experienced the competing risk (i.e., were found dead) then were no longer at risk of being found alive. If the sub-hazard ratio is above 1 for cats exposed to a factor relative to non-exposed cats, the sub-hazard and the cumulative incidence are higher in exposed cats.

Distances from where the cat went missing to where it was found were compared between cats found alive and those found dead using the Mann-Whitney (or Wilcoxon) rank sum test, using Stata’s-ranksum-command. Distances were also compared by cat’s prior exposure to outdoors using the Kruskal-Wallis test using Stata’s-kwallis-command and pair-wise comparison between those never allowed outside and each other category were performed using Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests. Respondents’ ranks for each of the four cat personality traits were compared by location where the cat was found using Kruskal-Wallis tests. Responses recorded as 0 were reallocated as 1 (‘not at all’). Responses of 5 indicated ‘perfectly describes my cat’s personality’; responses recorded as numbers greater than 5 were excluded from analysis of that trait. For Kruskal-Wallis tests, chi-squared statistic adjusted for ties were used.

Distributions of study cats were expressed as percentages of cats whose status for the attribute was recorded or could be deduced from the provided data. For questions where the respondent could choose one or more options, cats were only included when calculating percentages if at least one option was selected.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of Cats

In total, 1210 cats were recruited from 10 June to 17 August 2016. Of the 686 cats where country of residence was specified, most of the cats resided in the USA (59%), Australia (20%), and Canada (14%). Cats from 12 other countries were also recruited; these were from the United Kingdom (30 cats), and between 1 and 4 cats from each of Belgium, Bermuda, Brunei, Finland, France, Mexico, Philippines, Scotland, Spain, and South Africa.

Most cats were male (57%), most had been neutered (96%), and had been acquired from a shelter or rescue (33%) or from family or acquaintance (18%) (

Table 2). Half had gone missing 2 years or less prior to the date when the respondent completed the questionnaire (5th and 95th percentiles 4 days and 14 years, respectively).

The majority of cats (67%) were 1 to 7 years old when they went missing (

Table 2). Just over half of the cats (57% or 681/1196) had at least one form of identification (collars with no ID tag were not regarded as identification) and microchip was the most common form used (46% of all cats) (

Table 2). Other forms of identification used were, in decreasing order of frequency, collars with an ID tag, identification tattoo, and collar with a tracking device (

Table 2).

Nearly 90% of respondents strongly agreed with statements that they were attached to their missing cat and regarded it as a family member (

Table 3). The cat’s dwelling was most commonly a house, townhouse or condominium with a yard (77%) (

Table 2).

In the 6 months period prior to going missing, most cats were indoor-outdoor cats (69%), with 46% of all cats being allowed outdoors unsupervised. Some (28%) of respondents reported their cat was kept strictly indoors and never allowed outdoors (

Table 2). Of these cats, 42% had experience more than 6 months previously of the outdoors (

Table 2) and of all study cats, 85% had previous and/or recent experience of the outdoors.

Respondents ranked on a scale from 1 to 5 how well each of four personality descriptions fitted their cat, where 1 indicated ‘not at all’ and 5 indicated ‘perfectly describes my cat’s personality’. Ranks varied widely for ‘curious/clown cat’ and ‘cautious cat’ (n = 1049 and 1022 valid responses, respectively) but 62% of cats were scored 1 or 2 for ‘aloof cat’ (indicating that they were not aloof), and 73% of cats were scored 1 or 2 for ‘timid/fearful cat’ (indicating that they were not timid or fearful; n = 1004 and 1011 valid responses, respectively).

3.2. Circumstances Preceding and Leading to Cats Going Missing

At the time the cat went missing, 95% were in a familiar location and similar proportions of cats were indoors (37%), outdoors (25%), or had indoor-outdoor access (31%) (

Table 4). Of those cats that were indoors at time of disappearance whose escape route was known (

n = 403), the majority escaped through an open door or garage (74%). Of cats that were outdoors whose escape route was known (

n = 169), most escaped while outdoors without supervision (64%) (

Table 4). Of those cats that escaped while being transported (

n = 25), the majority escaped from the carrier (52%) (

Table 4). Most cats that disappeared from unfamiliar locations and whose escape route was known (

n = 57) escaped shortly after moving into a new house (51%) or from a friend or pet-sitter’s home (34%) (

Table 4).

3.3. Probabilities of Being Found Alive by Time Since Lost

Of the 1210 cats, the outcome could be determined for 1075 (

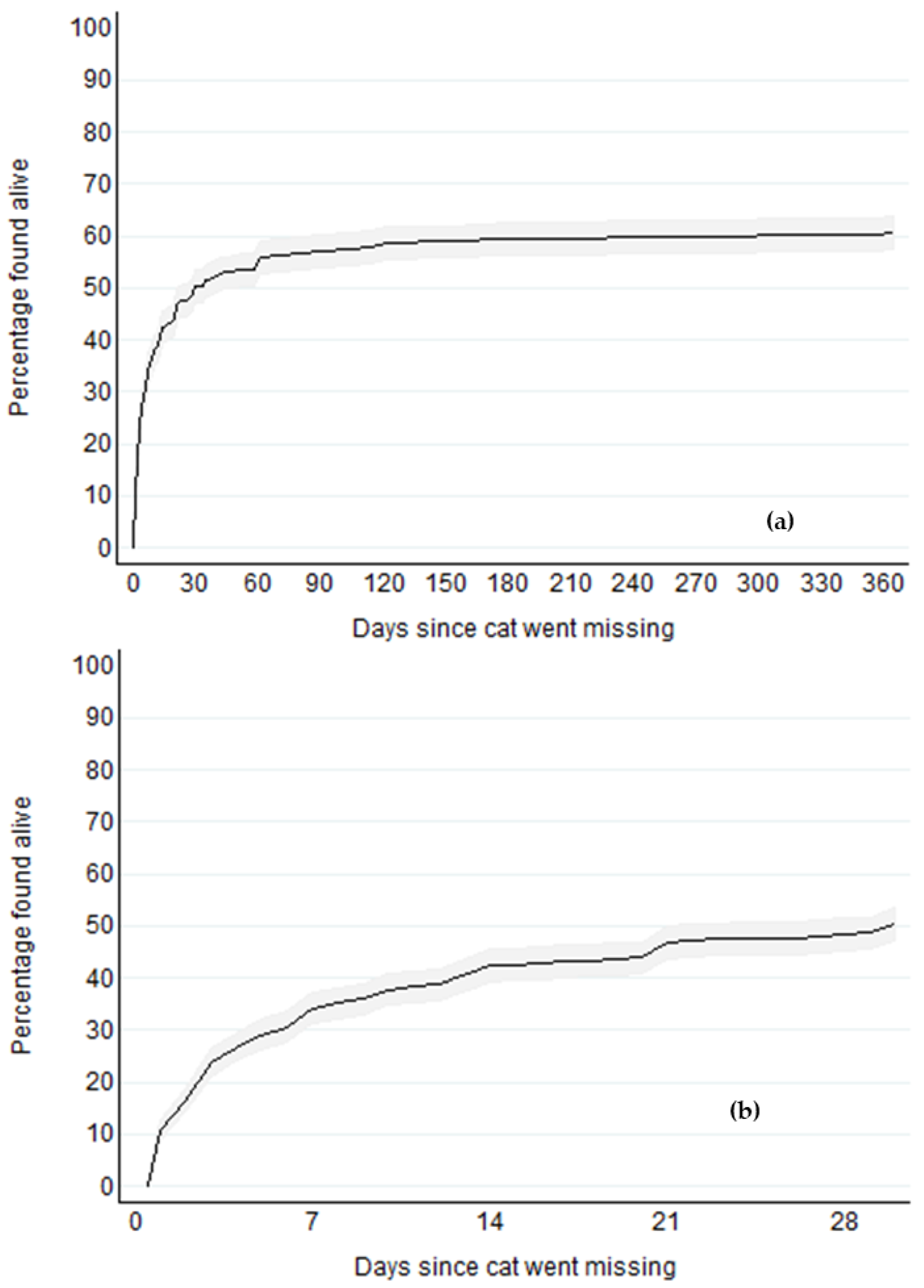

Table 1), and for 1044 of these cats, time from going missing to being found or, for cats not found, time to right-censoring (i.e., time since the cat went missing), were provided. Probabilities of an individual cat being found alive were calculated using these 1044 cats. Probabilities of an individual cat being found alive (i.e., cumulative incidences) by time since the cat went missing are shown in

Figure 1a,b. Of missing cats, approximately one-third (34%; 95% CI 31% to 37%) were found alive by day 7, 50% (95% CI 47% to 53%) by day 30, and 56% (95% CI 53% to 59%) by day 61. There was little increase in probability of being found alive after day 61. By one year, 61% of missing cats had been found alive (95% CI 57% to 64%) and this had increased to only 64% (95% CI 60% to 67%) by 4 years.

Of these 1044 cats, 601 were found alive, and the median time they remained lost was 6 days (25th and 75th percentiles 2 and 21 days, respectively). Of the 17 cats that were found dead, the median time they remained lost was 21 days (25th and 75th percentiles 6 and 91 days, respectively). For the 426 cats not found at the time the questionnaire was completed, the median time they had been lost for was 365 days (25th and 75th percentiles 35 and 1096 days, respectively).

3.4. Search Methods Used, Perceived Successful Methods, and Associations with the Cat Being Found Alive

To assess what methods were used to find each cat, respondents were offered five possible search methods—physically did a search, advertised, contacted a facility or sought professional help, used a trapping technique, and identification device. Respondents could select one or more of these, or they could indicate that they just waited for the cat to return. Of the 1044 cats whose time from going missing was provided, for 991, the respondent indicated what was done to find the cat. Distributions of these cats by search method and cat’s outcome are shown in

Table 5. Of respondents that used each method, the percentage who nominated that method as one that helped the most are also shown. For these 991 cats, the respondent used 0 (1%), 1 (18%), 2 (21%), 3 (35%), 4 (20%) or 5 (5%) of the five possible search methods. A physical search was the most common search method used (used for 96% of cats) and many people also advertised (74%) (

Table 5). Approximately half of respondents (57%) contacted a facility or sought professional help, with most of these contacting (83%) and/or visiting (53%) a shelter (

Table 5).

Outcomes are reported by search method in

Table 5. Where a physical search was conducted, 59% of cats were found alive. There was some evidence that cats were more likely to be found alive if physical searching was conducted than if no physical searching was conducted (

p = 0.071;

Table 5). Percentages of cats that were found alive were similar (57% to 62%) for all of the particular types of physical searching other than ‘drove around the area’ (52%;

Table 5). The relative time taken to find the cat alive due to the particular search method, relative to the time taken to find the cat alive by other methods or waiting, is shown in the right-hand column in

Table 5 (‘Where this method was used and the cat was found alive, % of those cats where this method helped the most’). A high percentage indicates that the particular search method was generally more rapid in resulting in the cat being found alive relative to the time that the alternative other methods and types and /or just waiting collectively took to result in the cat being found alive. Relative to other methods or waiting, the most rapid relative times taken to find the cat alive using a physical search strategy were when the search methods included ‘spoke with neighbors and asked them to look or assist in the search for my cat’, ‘walked around the area at night, using a flashlight (or spotlight)’, ‘asked and received neighbors’ permission to search their property using a slow methodical search’ and ‘searched my yard or the immediate area’ (

Table 5).

Where any type of advertising were used or if the owner contacted a facility or sought professional help at any stage, the cat was less likely to be ultimately found alive compared to if that search method was not conducted (

p < 0.001 for both;

Table 5). For most of the particular types of these methods, between 41% and 55% of cats were found alive (

Table 5). Of the advertising strategies, highest percentages of cats were found alive (52% to 55%) when fliers were distributed or posters mounted.

For cats with an identification device (microchip, ID tag etc.) where the owner contacted a facility or sought professional help, there was no evidence that cats were more likely to be found alive (

p = 0.331). Similarly, there was also no evidence that cats were more likely to be found alive with use of trapping techniques (

p = 0.307). For the particular trapping techniques and identification devices, 50% to 65% of cats were found alive (

Table 5). These associations between the various search methods and being found alive are univariable and did not account for time since the cat went missing when the search method was implemented.

3.5. Distances to Where Cat Found

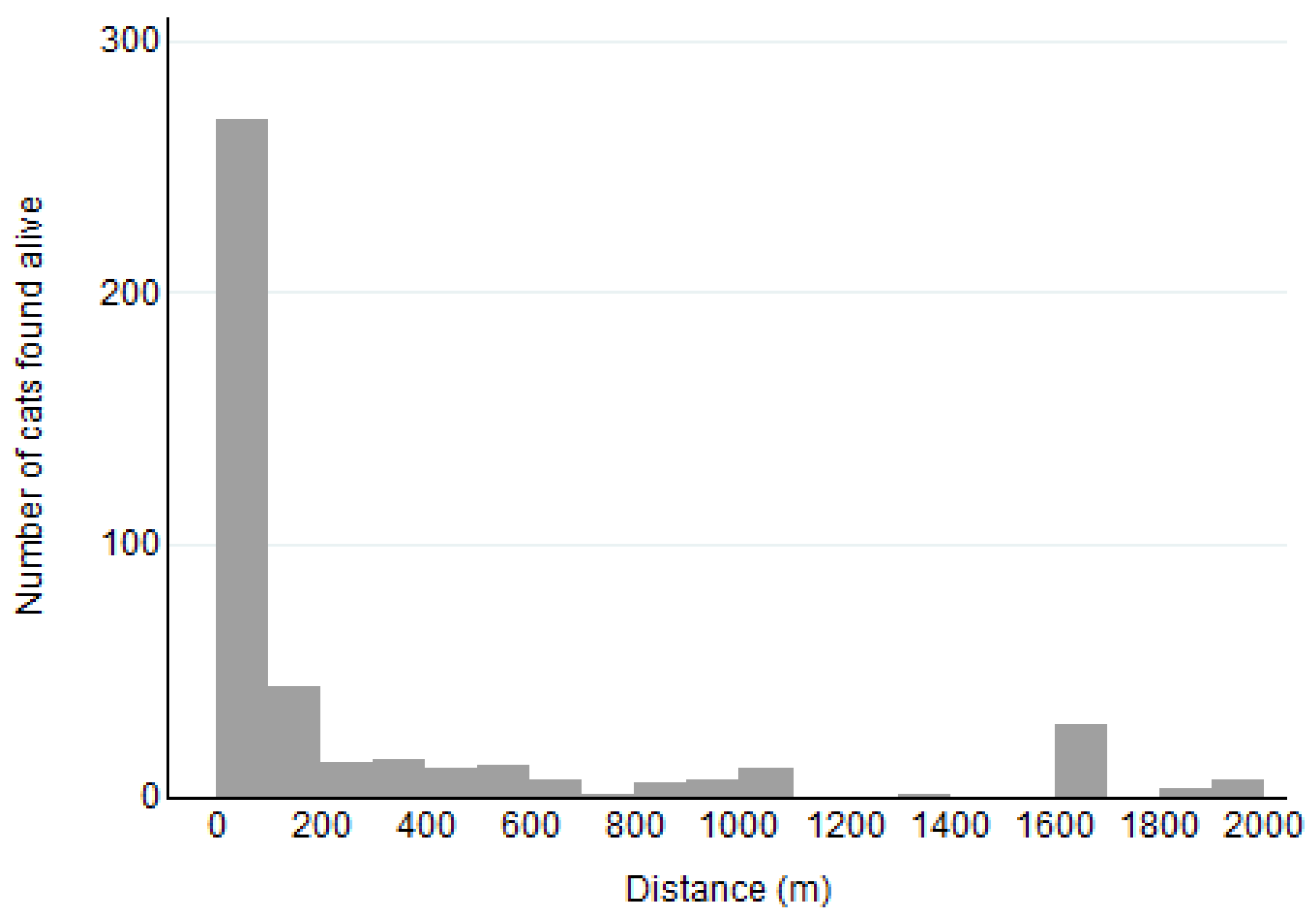

Of the 602 cats found alive, the distance from where the cat went missing to where it was found was recorded for 479 cats. Of these cats, 2 had implausibly high distances for cats to travel unassisted (>321 km) and these were disregarded. For the remaining 477 cats found alive, the median distance was 50 m (25th and 75th percentiles 9 and 500 m, respectively) (

Figure 2) with the maximum distance being 25 km. For the 17 cats found dead where distance was recorded, the median distance was 200 m (25th and 75th percentiles 91 and 500 m, respectively), with the maximum distance being 5 km (

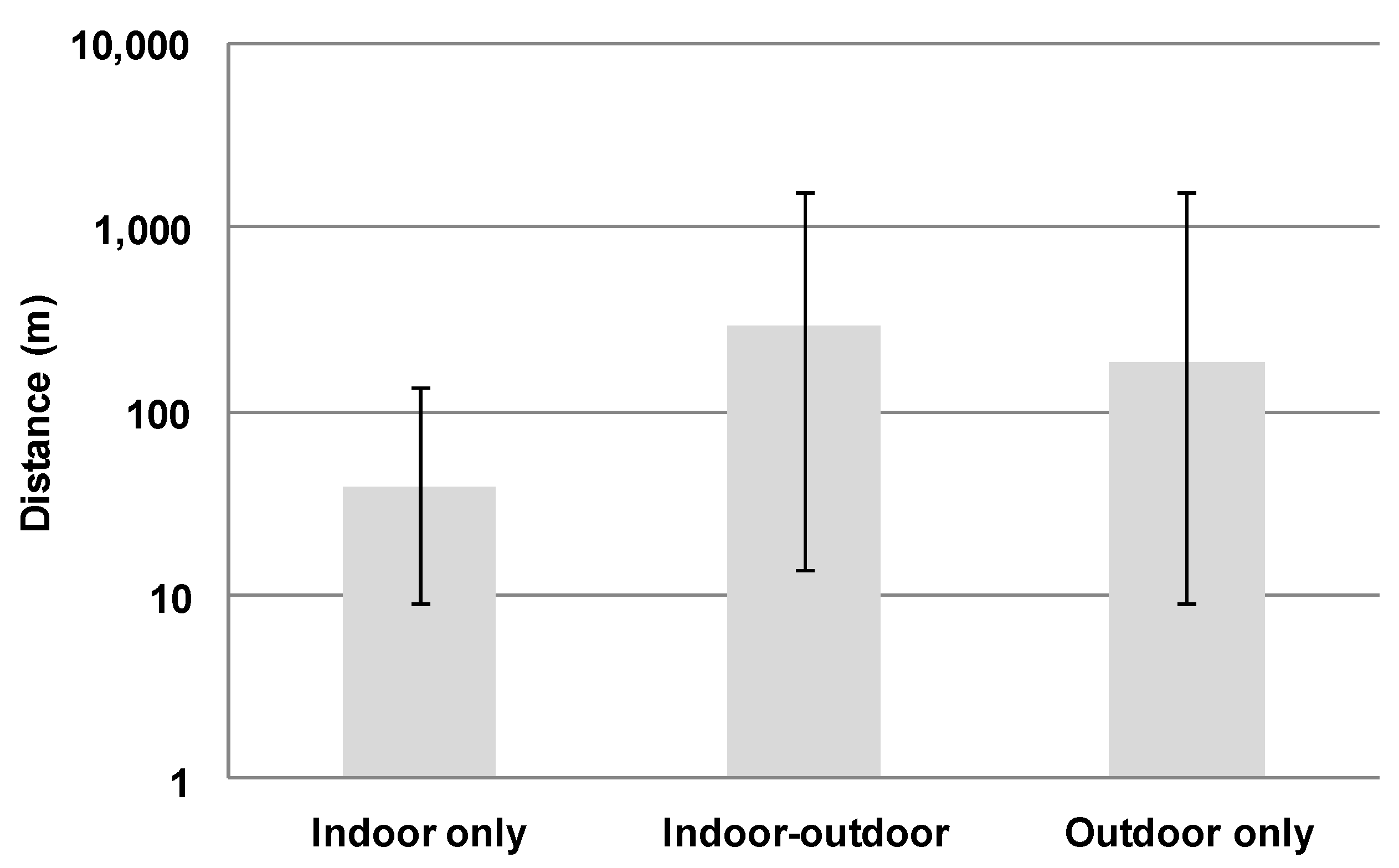

p = 0.07). Of cats found alive, distances varied by outside experience in the 6 months before going missing (overall

p < 0.001). Those cats that were indoor-outdoor and allowed outside unsupervised had longer distances compared with indoor cats that were never allowed outside (

p ≤ 0.001) (

Figure 3). The median distance for indoor-outdoor cats was 300 m (25th and 75th percentiles 14 and 1609 m (i.e., 1 mile), respectively;

n = 150 cats) and indoor-only cats was 39 m (25th and 75th percentiles 9 and 137 m, respectively;

n = 164 cats). Median distance for outdoor-only cats was 183 m (25th and 75th percentiles 9 and 1609m;

n = 15 cats). These did not differ significantly from indoor-only cats (

p = 0.173).

3.6. Locations Where Cats were Found and Cats’ Demeanors When Found

Of the cats that were found alive, the vast majority were found outside (83%) (

Table 6). This was followed by the option offered as ‘cat being found inside someone else’s house’ (11%), inside the house where they lived (4%), and inside a public building (2%) (

Table 6), therefore less than 2% of found cats were in a shelter or municipal animal facility. Specific locations are also shown in

Table 6. Under ‘other’, respondents commonly described their cat as “coming home by itself” or being found waiting at the front door or entrance points to the house. Other common responses were finding their cat near their house, their neighbor’s house, or in nearby woods, vegetation or roads.

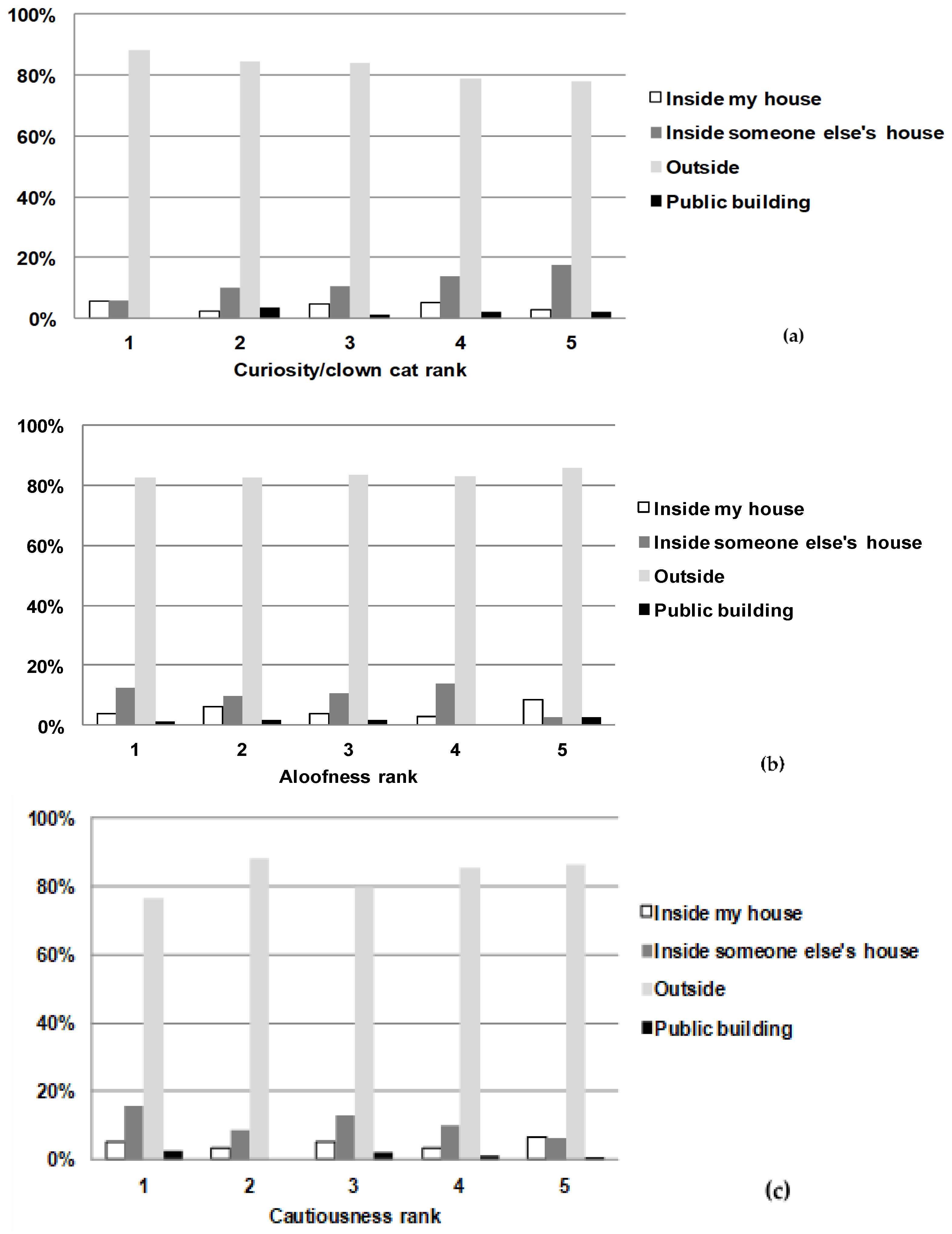

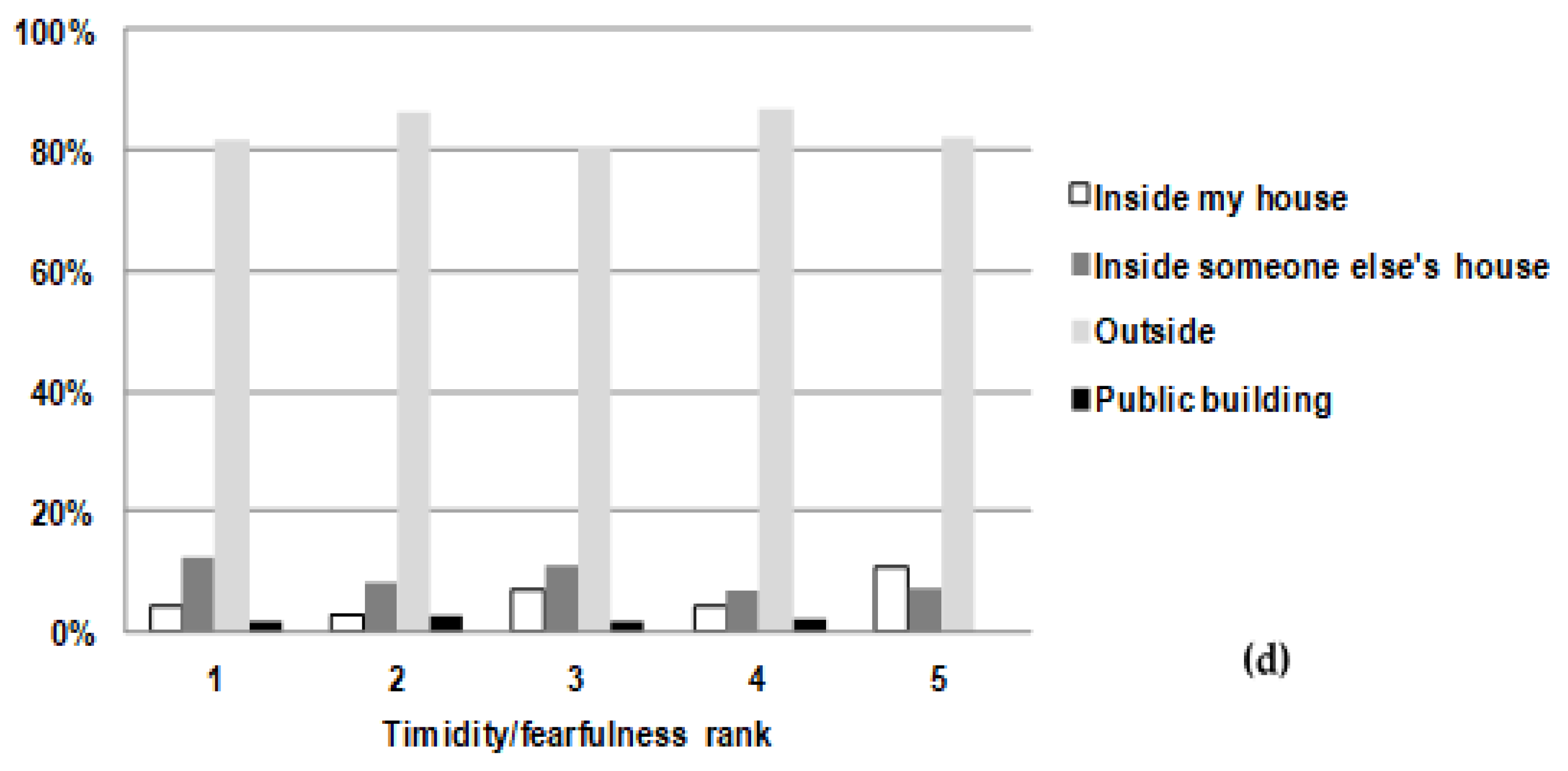

When looking at cats’ personalities with respect to location where the cat was found, for curious/clown cat, 6% of score 1 cats (indicating that they were not curious) were found inside someone else’s house compared with 10% of score 2 cats, 10% of score 3 cats, 14% of score 4 cats, and 17% of cats that were considered very curious (score 5) (

p = 0.005) (

Figure 4a). For the personality traits aloofness (

p = 0.848), cautiousness (

p = 0.123) and timidity/fearfulness (

p = 0.192), there were no consistent associations between percentages of cats found in each location and the personality trait (

Figure 4b–d).

Of the 585 cats that were found and at least one behavior when found was reported, only a minority (10%) of cats hissed or acted in a manner of a feral cat. Most cats appeared scared (50%), quiet but alert (30%), and/or friendly/relaxed (25%). A quarter of cats were vocalizing or meowing when found, and 9% were sick or injured when found.

4. Discussion

The outcomes of the present study provide valuable information on successful search methods to recover missing cats, likely locations where they are found, distances travelled and ways in which cats go missing. It also provides information on the likely locations where missing cats could be found based on their personalities and outdoor experience.

4.1. Locations of Missing Cats and Distances Travelled

An important finding was that most cats were found near their point of escape, with half being found within 50 m and three quarters within 500 m. This is in line with recent studies that have found most cats (66%) were recovered by either returning home on their own or being found in the neighboring vicinity (7%) [

10]. In the current study, indoor-only cats tended to be found nearer to their escape point compared with indoor-outdoor and outdoor-only cats, highlighting the importance of tailoring the distance radius of a physical search to the outdoor experience of the cat. A larger radius of search may be required to find cats that are indoor-outdoor or outdoor-only under no supervision (distance traveled 1600 m for up to 75% of cats) compared with strictly indoor cats (distance traveled 137 m for up to 75% of cats) and thus may require investing more time, effort and resources. Therefore, a search in a 200-m radius is more likely to suffice in a search for a missing indoor-only cat, but a search for an outdoor or indoor-outdoor cat is more likely to have to be extended up to 2 km radius or more.

Cats most commonly escaped into areas that had 7 or more places to hide in, such as nearby shrubbery, under motor vehicles, decks, porches, or in sheds. Most cats when found outside were hiding under porches, cars or under objects near the house where they resided. Of these cats, 18% were found directly outside the entrance points of the owner’s house (e.g., by the door or by the porch) or described as “simply came home”, which is in line with American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) observations that while “dogs are sought, cats come home” [

2,

8]. Our study has also shown that the personality of the cat may be indicative of the likely location where it will be, with cats described as highly curious more likely to be found inside someone else’s house or in public buildings. The percentage of missing cats found outside decreased steadily with increasing curiosity scores, and the percentage that were found inside someone else’s house increased steadily with increasing curiosity scores.

The finding that owned cats are often found not far from where they go missing provides evidence to support shelter-neuter and return (SNR) strategies, also known as return to field and cat diversion. This is a process whereby stray cats that are likely to be euthanized in shelters or animal control facilities are temporarily sheltered, then neutered and returned to the original location they were found as an alternative to euthanasia [

14]. The rationale for this is that lost owned, semi-owned and community cats who are cared for by people [

4,

15,

16], do not travel far from the location where they are fed. Our results also support returning unidentified owned, semi-owned and community cats to their home territory as an alternative to euthanasia. Shelter-neuter and return strategies markedly reduce euthanasia in facilities with large intakes of stray cats, and are also reported to reduce intake of stray cats [

14].

4.2. Search Timing and Methods

Of the cats found alive, almost all were recovered within the first 2 months, with approximately half recovered within the first 7 days. This was probably largely because cats that were in situations making them easier to find were, accordingly, found more quickly. However, it may also have been partly because finding cats soon after they go missing prevents such cats from being harmed or subsequently becoming irretrievably lost if not found quickly. Physical searching, advertising, and contacting a facility or seeking professional assistance were the 3 most common search methods used. Physical searching was used most commonly, and there was some evidence that the probability of recovering a missing cat alive is increased if this method is conducted. More specifically, the most successful physical search strategies were ‘searched my yard and the immediate area’, ‘while I was looking for my cats, I called its name’, ‘walked around the area during daylight hours’ and ‘spoke with neighbors and asked them to look or assist in the search for my cat’.

Cats were less likely to be found alive if any type of advertising were used, or if the owner contacted a facility or sought professional help. As these strategies are unlikely to reduce the probability of missing cats being found alive, these observed associations were probably due to selective implementation of these strategies more commonly when lost cats had not been found for some time, and thus already had reduced chances of being found alive. As our study was retrospective, it was not possible to collect the chronology of search strategies. These data may be collectable in prospective studies. If available, confounding for this reason should be reduced if effects of various search strategies were assessed using survival analysis with search strategies fitted as time-varying covariates. In addition, for many lost cats, multiple search strategies are used, and multivariable models would be useful when assessing the effect of particular search strategies

Fifty seven percent of cats were recovered alive if pet detective or volunteer lost pet recovery service was used. This probably reflects the ability of these services to provide appropriate advice and use efficient methods for the recovery of the missing cat, such as conducting a thorough physical search, distributing flyers and using a humane trap. Although less than 2% of cats found alive were in a shelter, 36% of respondents who found their cat alive and visited or called a shelter rated it as one of the two most helpful methods, possibly because shelter staff provided advice on appropriate search methods to be used.

Only approximately half of the study cats were microchipped, emphasizing the importance of minimum holding periods in shelters and animal control facilities to allow time for owners of non-microchipped cats to search for them. In the current study, microchipping was not found to improve the chance of missing cats being found alive. This may have been because few lost cats were taken to a facility where microchips can be read (shelter, animal control facility or veterinary clinic). It may also have been due, in part, to the fact that for recovery via microchipping, it must have updated owner’s contact details. For a substantial proportion of microchipped dogs and cats (37% in one study [

17]), the chip was registered to incorrect owner data such as the cat’s previous owner, or incorrect or disconnected phone lines, or the microchip was not properly registered. The proportion of animals reclaimed from a shelter declines significantly if microchipped animals have data problems (41% compared to 75% for microchipped cats with no such data problems [

17].

4.3. Respondent and Missing Cat-Related Demographics

The respondents in this study seemed to have a strong human-pet bond with their cat compared with the general population. Of all respondents, 90% answered they were strongly attached to their pet and regarded them as a family member. This is a higher proportion than in other studies of pet owners in Western countries describing a strong human-pet bond [

18,

19,

20,

21], and only 35–45% of respondents in one survey would have regarded their pet (dog or cat) as a family member [

18]

4.4. Limitations

There were likely to have been recall errors in the reported study data as a substantial proportion of respondents (71%) had lost their cat more than 6 months ago prior to the date when they completed the questionnaire, with the median duration being 731 days (i.e., 2 years). This may have caused misclassification of related variables, possibly distorting measures of association and reducing the statistical power of the study. The strong human-animal attachment respondents reported having with their cat could also mean that respondents and thus their responses are not representative of the general population, but of a sub-sample of the general population that is more closely bonded to their cat than average. The generalizability of the findings may thus be limited, e.g., the study population may have comprised people more likely to put in more effort to find their cat than the average pet owner.

The exact proportion of cats found in a shelter or animal control facility was not able to be ascertained because of an oversight in the questionnaire design, however based on results, this represented less than 2% of cats found alive. Analysis of recovery by microchipping was challenging to interpret because any benefits of microchipping would only be expected if the cat was taken to a location where a scanner was available. Benefits of microchipping could also be affected by the duration of the minimum holding period for cats in the facility, and accuracy of the owner contact details in animal identification databases.

Our analyses did not sub-divide cats into those that were indoor-only cats versus those that had had outdoor experience. Cat’s experience with the outside world could affect their behaviors when displaced with respect to distance travelled, location found and likelihood of recovery. Future studies in this field could look into analyzing how these two groups of cats behave and how that may affect the effectiveness of search methods and probabilities of recovery.

In this study, cats found dead were found further away than cats found alive. It is possible this could be a misrepresentation if, for example, the cats found deceased were actually admitted into a shelter, animal control facility or veterinary clinic by a member of the public before the owner was notified. Similarly, those found deceased close to home were less likely to be classified as “missing” by their owners. As the sample group was small (1.7% of total cats in the study), analysis for this category of cats was limited.