Exploring Attitudes and Beliefs towards Implementing Cattle Disease Prevention and Control Measures: A Qualitative Study with Dairy Farmers in Great Britain

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

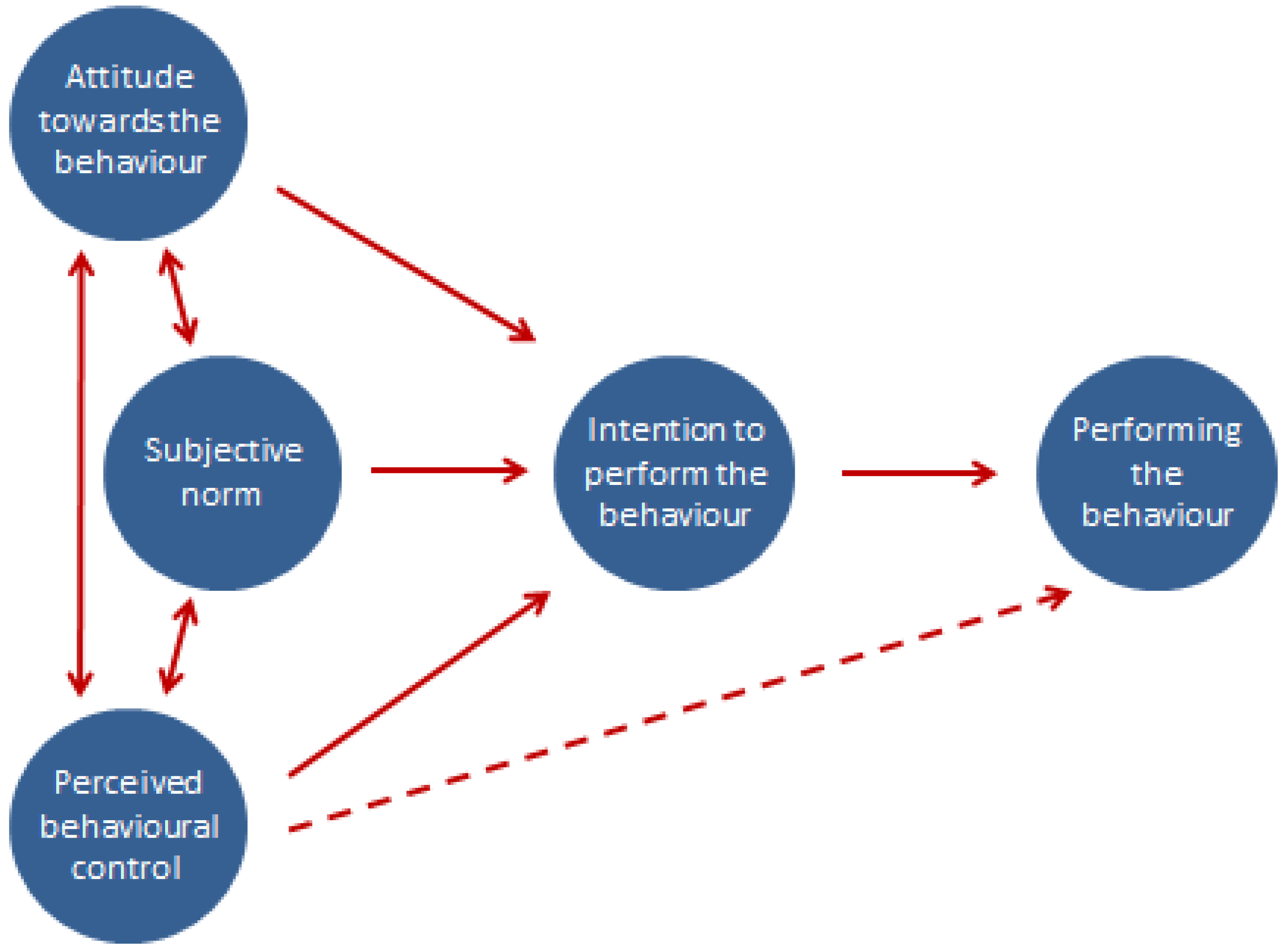

- Behavioural belief (Attitude towards the behaviour)—The belief that a behaviour leads to a certain outcome, for example, a farmer feels that by implementing biosecurity measures, the productivity of their cattle will subsequently improve.

- Normative belief (Subjective norm)—The belief that particular individuals or groups think a person should or should not perform the behaviour, for example, a farmer believes his/her milk buyer thinks it is important that he/she implements biosecurity measures on his/her farm.

- Control belief (Perceived behavioural control)—Someone’s perception of their own ability to perform a behaviour, for example, how able a farmer feels they are to prevent diseases coming onto their farm.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

2.2. Participant Selection

2.3. Farmer Recruitment

2.4. Farmer Interviews

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. General Findings

“I think it’s quite highly likely to get disease in. Especially if you’re buying in stock, which I’m not doing. But dairy farms have an awful lot of visitors and different people coming through, which could potentially be possibly carrying or unknowingly carrying disease. It just takes your neighbours who have got the disease to go and put something in your field. I don’t think we’re immune to it, no.”(F10)

3.2. Behavioural Beliefs

“We have, we are very strict about keeping a close monitoring (of) them, a close eye on the animals so that if there is something that goes amiss that you are there at the beginning rather than you know towards the disastrous stage.”(F7)

“It’s just about being conscientious about your animals’ health status and trying to protect it at all costs.”(F3)

However, the alternative argument was also made in relation to having disease on farms resulting in “protective exposure”.

F6’s experience with the introduction of digital dermatitis into a closed herd: “…there’s a certain amount of resistance that definitely develops with the cows we have now because they have had it all the way through…”

“But, you know, I could spend hundreds of pounds on chemicals to try and keep everything clean, and spend hours and hours keeping it all clean, but at the end of the day the chances are we’re not likely to get that disease anyway, or whatever. Some of the big ones only come every once in a blue moon hopefully.”(F8)

“And quite a lot of those cows are actually slaughtered unnecessarily because the test (for bovine tuberculosis) in cattle is not very reliable.”(F13)

“…Because you can put a lot of effort into it and give yourself ten out of ten for what you’re doing…There’s a lot of backdoor ways or other routes into the farm for disease problems to come that are beyond your control.”(F4)

“…because all of these things are alright in isolation but when we are not really being paid sufficiently for our product to cover all of the time that they then spend, then you know you have to look at that and think well actually you know is it more important to do that or to go in and monitor the cows that are calving in the next field. You have to make day to day assessments of where your time is best spent.”(F7)

3.3. Normative Beliefs

“Er, I wanted to introduce more Jersey into the herd, the vet said breed it in yourself, whatever you do, don’t buy anything in because your herd health status is so high, don’t risk buying in any other diseases.”(F4)

“Well, at the moment it’s just a closed herd, so we’re obviously not bringing animals in. And then if there was a threat of a disease from a neighbouring farm I would speak to the vet and take his advice and go from there.”(F9)

“Well, DEFRA bring out some quite extraordinary rules but they don’t seem to want…they don’t seem to work. They don’t seem to be practical enough. It’s just, a lot of farmers think it’s just to keep people in work thinking up the next rule and regulation.”(F20)

“I mean I suppose DEFRA would like to think it is sort of them but they often don’t make a very good job of it…”(F19)

“Well, in general, I think the public want you to use as little medicine as possible. I think—and they’re probably…generally…they want you to use preventative measures, probably want you to use preventative measures than actual using medicines, I’d say that would be.”(F11)

“Well I think lots of people have got opinions, probably agriculture suffers, more from other people’s perceptions and their opinions derived from those perceptions than any other industry. I mean we all have opinions on the health service and the police service and all the rest of it. But I think because we are, we’ve come from hunter gatherers everybody feels they have got the right to have an opinion on the land, on the way we produce our products from our animals. And I have got no problem with that except for a lot of it is you know a little bit of information is dangerous.”(F7)

3.4. Control Beliefs

“I just take a decision on a daily/monthly/yearly basis which may or may not vary, for instance things altering, there’s a foot and mouth outbreak obviously we shut the farm gate and we let virtually no one on.”(F23)

“If it comes to the push, yes, just shut the gates and stop anybody coming in.”(F2)

“I think really like highly infectious airborne diseases I have got no control over. You know if we get foot and mouth come through, I mean short of putting snipers on the farm borders and shooting everything that crosses across including birds and everything else, you know I mean prevent everything…”(F6)

“If you’re trying to, it’s very hard to try and keep TB out, unless you fence all your farm with ten feet high fences so that the deer can’t come over, dig it ten feet deep in the ground so the badgers can’t bore underneath it and that’s the only way you can stop it.”(F20)

“I’ve had that (Schmallenberg). There’s nothing I can do about that, I don’t think. If it’s midges flying, you know, across the Channel or whatever, and they attack my cows, that’s the way it is, there’s not much I can do with that. So no, I don’t think I can do much for that sort of thing.”(F8)

“Well, we do it, we’re doing our best but um, we can only do so much.”(F20)

“You know, you can only, you can only do so much, you can only do foot bathing and, um, well, nobody really has got the time to wash themselves down with disinfectant.”(F1)

3.5. Specific Factors Encouraging Farmers to Implement Biosecurity Measures

“…If there’s serious contagious disease in or near the farm or not in the farm, in or near, in the country or near the farm then that’s what we would do.”(F23)

“…so we try to keep it away from other cattle. We don’t do anything else I don’t think, too much. The disinfecting side, it sort of was very popular when we were—with Foot and Mouth—but after that it seems to have died a death now.”(F24)

“Well, we have them tested to see what we’ve got. And then we, you know, go by that, rather than just injection willy-nilly for this that and the other. There’s no point trying to prevent something they haven’t got is it?”(F18)

“Biosecurity on a farm is, it’s a bit of a, I don’t know, it’s kind of a tricky thing because we all know what we should do but what actually gets done is very little until you have actually a problem…but if there was an outbreak I’d have a foot dipper, a wheel wash up. So biosecurity is kind of, it’s doing the least possible when necessary.”(F6)

“And then if there was a threat of a disease from a neighbouring farm I would speak to the vet and take his advice and go from there.”(F9)

“If it worked, if it was shown to work. It’s no good making yourself do more work than you have to is there. Farming’s hard enough.”(F20)

“What would make (you take up a new biosecurity measure)—well, if it was guaranteed to do something I’d perhaps do it. If it was feasible and economical and not too difficult. But feasibility and economical would be the best bet. If I knew it was—if I knew it cost me five pounds to implement something and took me no time at all to do it, and it was earning me ten quid, then you’re quite happy, aren’t you, really?”(F8)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide for the Farmer Interviews

References

- Anderson, J. Biosecurity: A new term for an old concept: How to apply it. Bov. Pract. 1998, 32, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, G.; Stott, A.; Humphry, R. Modelling and costing BVD outbreaks in beef herds. Vet. J. 2004, 167, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, D.A. Economic aspects of agricultural and food biosecurity. Biosecur. Bioterror. Biodef. Strategy Pract. Sci. 2008, 6, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frössling, J.; Nöremark, M. Differing perceptions—Swedish farmers’ views of infectious disease control. Vet. Med. Sci. 2016, 2, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, E.; Brennan, M.; Barkema, H.; Wapenaar, W. A questionnaire-based survey on the uptake and use of cattle vaccines in the UK. Vet. Rec. Open 2014, 1, e000042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, R.G.; Sayers, G.P.; Mee, J.F.; Good, M.; Bermingham, M.L.; Grant, J.; Dillon, P.G. Implementing biosecurity measures on dairy farms in Ireland. Vet. J. 2013, 197, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrazin, S.; Cay, A.B.; Laureyns, J.; Dewulf, J. A survey on biosecurity and management practices in selected Belgian cattle farms. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 117, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nöremark, M.; Frössling, J.; Lewerin, S.S. Application of routines that contribute to on-farm biosecurity as reported by Swedish livestock farmers. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2010, 57, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahlström, L.; Virtanen, T.; Kyyrö, J.; Lyytikäinen, T. Biosecurity on Finnish cattle, pig and sheep farms—Results from a questionnaire. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 117, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, R.; Good, M.; Sayers, G. A survey of biosecurity-related practices, opinions and communications across dairy farm veterinarians and advisors. Vet. J. 2014, 200, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, K.; Wapenaar, W.; Brennan, M.L. Cattle veterinarians’ awareness and understanding of biosecurity. Vet. Rec. 2015, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottoms, K.; Dewey, C.; Richardson, K.; Poljak, Z. Investigation of biosecurity risks associated with the feed delivery: A pilot study. Can. Vet. J. 2015, 56, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heffernan, C.; Nielsen, L.; Thomson, K.; Gunn, G. An exploration of the drivers to bio-security collective action among a sample of UK cattle and sheep farmers. Prev. Vet. Med. 2008, 87, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, M.L.; Christley, R.M. Cattle producers’ perceptions of biosecurity. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garforth, C.J.; Bailey, A.P.; Tranter, R.B. Farmers’ attitudes to disease risk management in England: A comparative analysis of sheep and pig farmers. Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 110, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, L.; Stott, A.W.; Heffernan, C.; Ringrose, S.; Gunn, G.J. Determinants of biosecurity behaviour of British cattle and sheep farmers—A behavioural economics analysis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 108, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Abraham, C. Interventions to change health behaviours: Evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychol. Health 2004, 19, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behaviour relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willock, J.; Deary, I.J.; McGregor, M.M.; Sutherland, A.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Morgan, O.; Dent, B.; Grieve, R.; Gibson, G.; Austin, E. Farmers’ attitudes, objectives, behaviours, and personality traits: The Edinburgh study of decision making on farms. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K. Theory at A Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice, 2nd ed.; NIH: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, R.J. Reconceptualising the “behavioural approach” in agricultural studies: A socio-psychological perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M.; Zimmerman, R.S. Health behaviour theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviours: Are we moving in the right direction? Health Educ. Res. 2005, 20, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garforth, C.; Rehman, T.; McKemey, K.; Tranter, R.; Cooke, R.; Yates, C.; Park, J.; Dorward, P. Improving the design of knowledge transfer strategies by understanding farmer attitudes and behaviour. J. Farm Manag. 2004, 12, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Iversen, J.; Cook, A.J.; Watson, E.; Nielen, M.; Larkin, L.; Wooldridge, M.; Hogeveen, H. Perceptions, circumstances and motivators that influence implementation of zoonotic control programs on cattle farms. Prev. Vet. Med. 2010, 93, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeeva, N.; van Asseldonk, M.; Backus, G. Perceived risk and strategy efficacy as motivators of risk management strategy adoption to prevent animal diseases in pig farming. Prev. Vet. Med. 2011, 102, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, A.-K.; Thomsen, P.T.; Rintakoski, S.; Espetvedt, M.N.; Wolff, C.; Houe, H. The association between farmers’ participation in herd health programmes and their behaviour concerning treatment of mild clinical mastitis. Acta Vet. Scand. 2012, 54, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, A.H.; Norby, B.; Dean, W.R.; McIntosh, W.A.; Scott, H.M. Utilizing qualitative methods in survey design: Examining Texas cattle producers’ intent to participate in foot-and-mouth disease detection and control. Prev. Vet. Med. 2012, 103, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruijnis, M.; Hogeveen, H.; Garforth, C.; Stassen, E. Dairy farmers’ attitudes and intentions towards improving dairy cow foot health. Livest. Sci. 2013, 155, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espetvedt, M.; Lind, A.-K.; Wolff, C.; Rintakoski, S.; Virtala, A.-M.; Lindberg, A. Nordic dairy farmers’ threshold for contacting a veterinarian and consequences for disease recording: Mild clinical mastitis as an example. Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 108, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jääskeläinen, T.; Kauppinen, T.; Vesala, K.; Valros, A. Relationships between pig welfare, productivity and farmer disposition. Anim. Welf. 2014, 23, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, P.; Wieland, B.; Mateus, A.L.; Dewberry, C. Pig farmers’ perceptions, attitudes, influences and management of information in the decision-making process for disease control. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 116, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, A.H.; Norby, B.; Scott, H.M.; Dean, W.; McIntosh, W.A.; Bush, E. Distribution of cow-calf producers’ beliefs about reporting cattle with clinical signs of foot-and-mouth disease to a veterinarian before or during a hypothetical outbreak. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 117, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortall, O.; Ruston, A.; Green, M.; Brennan, M.; Wapenaar, W.; Kaler, J. Broken biosecurity? Veterinarians’ framing of biosecurity on dairy farms in England. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 132, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G.; Kok, G. The theory of planned behaviour: A review of its applications to health-related behaviours. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 11, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potente, S.; Coppa, K.; Williams, A.; Engels, R. Legally brown: Using ethnographic methods to understand sun protection attitudes and behaviours among young Australians “I didn’t mean to get burnt—It just happened!”. Health Educ. Res. 2011, 26, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.M.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Obst, P.L.; Graves, N.; Barnett, A.; Cockshaw, W.; Gee, P.; Haneman, L.; Page, K.; Campbell, M.; et al. Using a theory of planned behaviour framework to explore hand hygiene beliefs at the “5 critical moments” among Australian hospital-based nurses. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, J.; Van Schaik, G.; Renes, R.; Lam, T. The effect of a national mastitis control program on the attitudes, knowledge, and behaviour of farmers in The Netherlands. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 5737–5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryman, A. Sampling in qualitative research. In Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 415–429. [Google Scholar]

- DEFRA. Field Services Offices (Animal Health & Welfare). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/animal-and-plant-health-agency/about/access-and-opening#field-services-offices-animal-health--welfare (accessed on 23 September 2016).

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, L.; Stavisky, J.; Dean, R. What is a feral cat? Variation in definitions may be associated with different management strategies. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2013, 15, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scottish Government. The Scottish Bvd Eradication Scheme. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/farmingrural/Agriculture/animal-welfare/Diseases/disease/bvd/eradication (accessed on 23 September 2016).

- TB Hub. Available online: http://www.tbhub.co.uk/ (accessed on 23 September 2016).

- Brownlie, J.; Thompson, I.; Curwen, A. Bovine virus diarrhoea virus-strategic decisions for diagnosis and control. Practice 2000, 22, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson-West, P. “Trusting blindly can be the biggest risk of all”: Organised resistance to childhood vaccination in the UK. Sociol. Health Illn. 2007, 29, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S.; Fozdar, F.; Sully, M. The effect of trust on West Australian farmers’ responses to infectious livestock diseases. Sociol. Rural. 2009, 49, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, G.; Heffernan, C.; Hall, M.; McLeod, A.; Hovi, M. Measuring and comparing constraints to improved biosecurity amongst GB farmers, veterinarians and the auxiliary industries. Prev. Vet. Med. 2008, 84, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enticott, G.; Franklin, A.; Van Winden, S. Biosecurity and food security: Spatial strategies for combating bovine tuberculosis in the UK. Geogr. J. 2012, 178, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Jover, M.; Gilmour, J.; Schembri, N.; Sysak, T.; Holyoake, P.; Beilin, R.; Toribio, J.A. Use of stakeholder analysis to inform risk communication and extension strategies for improved biosecurity amongst small-scale pig producers. Prev. Vet. Med. 2012, 104, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richens, I.F.; Hobson-West, P.; Brennan, M.L.; Lowton, R.; Kaler, J.; Wapenaar, W. Farmers’ perceptions of the role of veterinary surgeons in vaccination strategies on British dairy farms. Vet. Rec. 2015, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruston, A.; Shortall, O.; Green, M.; Brennan, M.; Wapenaar, W.; Kaler, J. Challenges facing the farm animal veterinary profession in England: A qualitative study of veterinarians’ perceptions and responses. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 127, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, M.D.; Rouner, D. Value-affirmative and value-protective processing of alcohol education messages that include statistical evidence or anecdotes. Commun. Res. 1996, 23, 210–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Jansen, J.; Van den Borne, B.; Renes, R.; Hogeveen, H. What veterinarians need to know about communication to optimise their role as advisors on udder health in dairy herds. N. Z. Vet. J. 2011, 59, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerlich, B.; Wright, N. Biosecurity and insecurity: The interaction between policy and ritual during the foot and mouth crisis. Environ. Values 2006, 15, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadori, L.; Savio, S.; Nicotra, E.; Rumiati, R.; Finucane, M.; Slovic, P. Expert and public perception of risk from biotechnology. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Presseau, J.; Araújo-Soares, V. Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, J.A. Ritual and magic in the control of contagion. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1957, 22, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year Published | Citation | Subject | Population | Health Psychology Model Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garforth et al., 2004 | [23] | Knowledge and technologies transfer strategies | Cattle and sheep farmers | TRA |

| Ellis-Iversen et al., 2010 | [24] | Zoonotic disease control | Cattle farmers | TPB/SEM |

| Valeeva et al., 2011 | [25] | Risk of animal disease and risk management strategies | Pig farmers | HBM |

| Lind et al., 2012 | [26] | Mastitis | Cattle farmers | TPB |

| Delgado et al., 2012 | [27] | Foot and mouth disease detection and control | Cattle farmers | TPB |

| Bruijnis et al., 2013 | [28] | Foot health | Cattle farmers | TPB |

| Espetvedt et al., 2013 | [29] | Contact with veterinarian (mastitis) | Cattle farmers | TPB |

| Garforth et al., 2013 | [15] | Disease risk management | Sheep and pig farmers | TRA/TPB/HBM |

| Jaaskelainen et al., 2014 | [30] | Animal welfare and production; farmer disposition | Pig farmers | TPB |

| Alarcon et al., 2014 | [31] | Disease control | Pig farmers | TPB |

| Delgado et al., 2014 | [32] | Movement ban compliance during FMD control | Cattle farmers | TPB |

| Shortall et al., 2016 | [33] | Biosecurity | Cattle farmers | SEM |

| Herd Size and Type | Scotland | Wales | South West | South East | Midlands | North |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (Conventional) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Medium (Conventional) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Large (Conventional) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Organic | Medium | Medium | Large | Large | Medium | Medium |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brennan, M.L.; Wright, N.; Wapenaar, W.; Jarratt, S.; Hobson-West, P.; Richens, I.F.; Kaler, J.; Buchanan, H.; Huxley, J.N.; O’Connor, H.M. Exploring Attitudes and Beliefs towards Implementing Cattle Disease Prevention and Control Measures: A Qualitative Study with Dairy Farmers in Great Britain. Animals 2016, 6, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6100061

Brennan ML, Wright N, Wapenaar W, Jarratt S, Hobson-West P, Richens IF, Kaler J, Buchanan H, Huxley JN, O’Connor HM. Exploring Attitudes and Beliefs towards Implementing Cattle Disease Prevention and Control Measures: A Qualitative Study with Dairy Farmers in Great Britain. Animals. 2016; 6(10):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6100061

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrennan, Marnie L., Nick Wright, Wendela Wapenaar, Susanne Jarratt, Pru Hobson-West, Imogen F. Richens, Jasmeet Kaler, Heather Buchanan, Jonathan N. Huxley, and Heather M. O’Connor. 2016. "Exploring Attitudes and Beliefs towards Implementing Cattle Disease Prevention and Control Measures: A Qualitative Study with Dairy Farmers in Great Britain" Animals 6, no. 10: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6100061

APA StyleBrennan, M. L., Wright, N., Wapenaar, W., Jarratt, S., Hobson-West, P., Richens, I. F., Kaler, J., Buchanan, H., Huxley, J. N., & O’Connor, H. M. (2016). Exploring Attitudes and Beliefs towards Implementing Cattle Disease Prevention and Control Measures: A Qualitative Study with Dairy Farmers in Great Britain. Animals, 6(10), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6100061