Dynamics and Health Risks of Fungal Bioaerosols in Confined Broiler Houses During Winter

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Sites and Poultry House Environment

2.2. Determination of Fungal Aerosol Size Distribution and Concentration

2.3. Air Sample Collection for Fungal Community Analysis

2.4. DNA Extraction and ITS High-Throughput Sequencing

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

3. Results

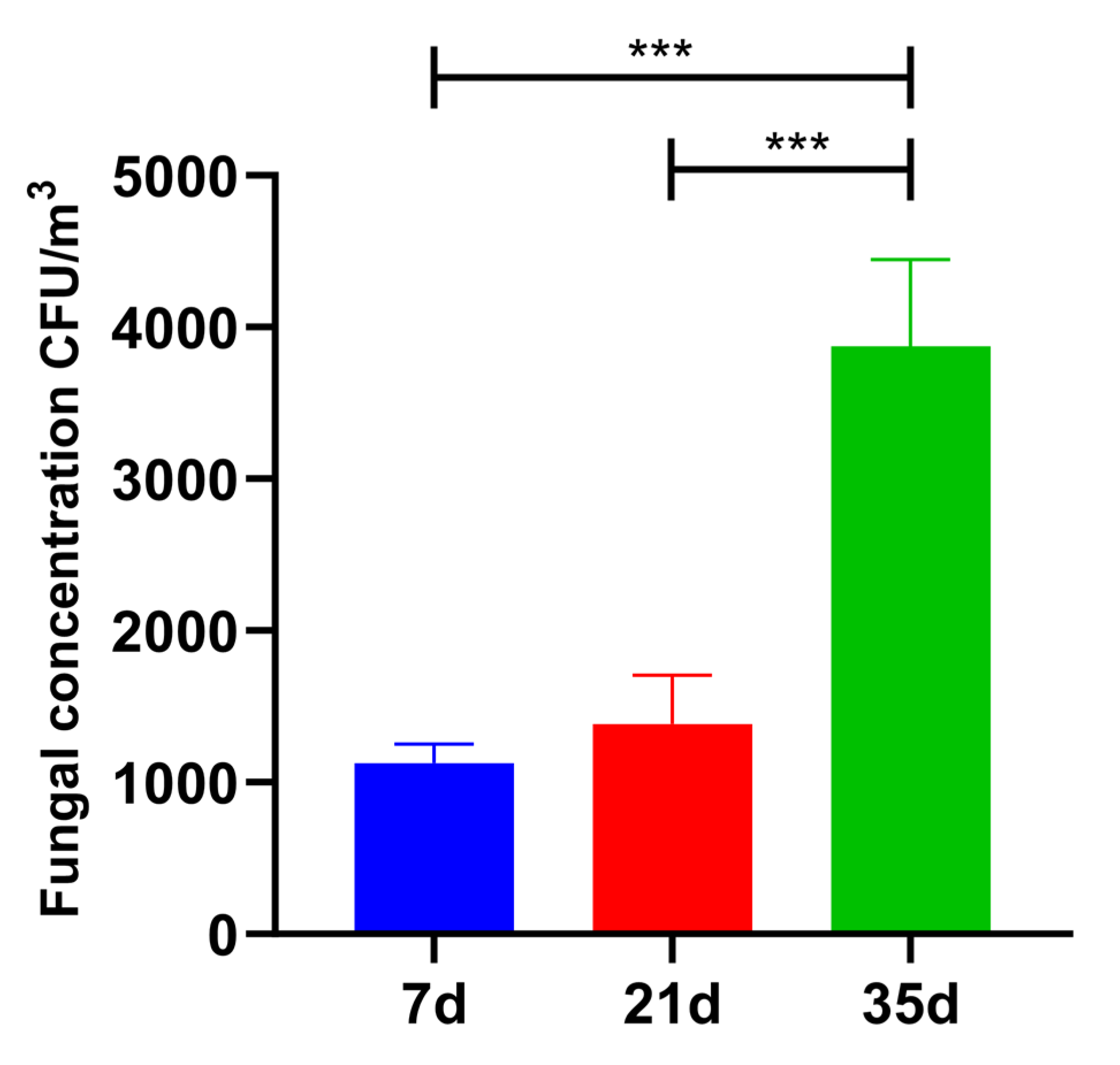

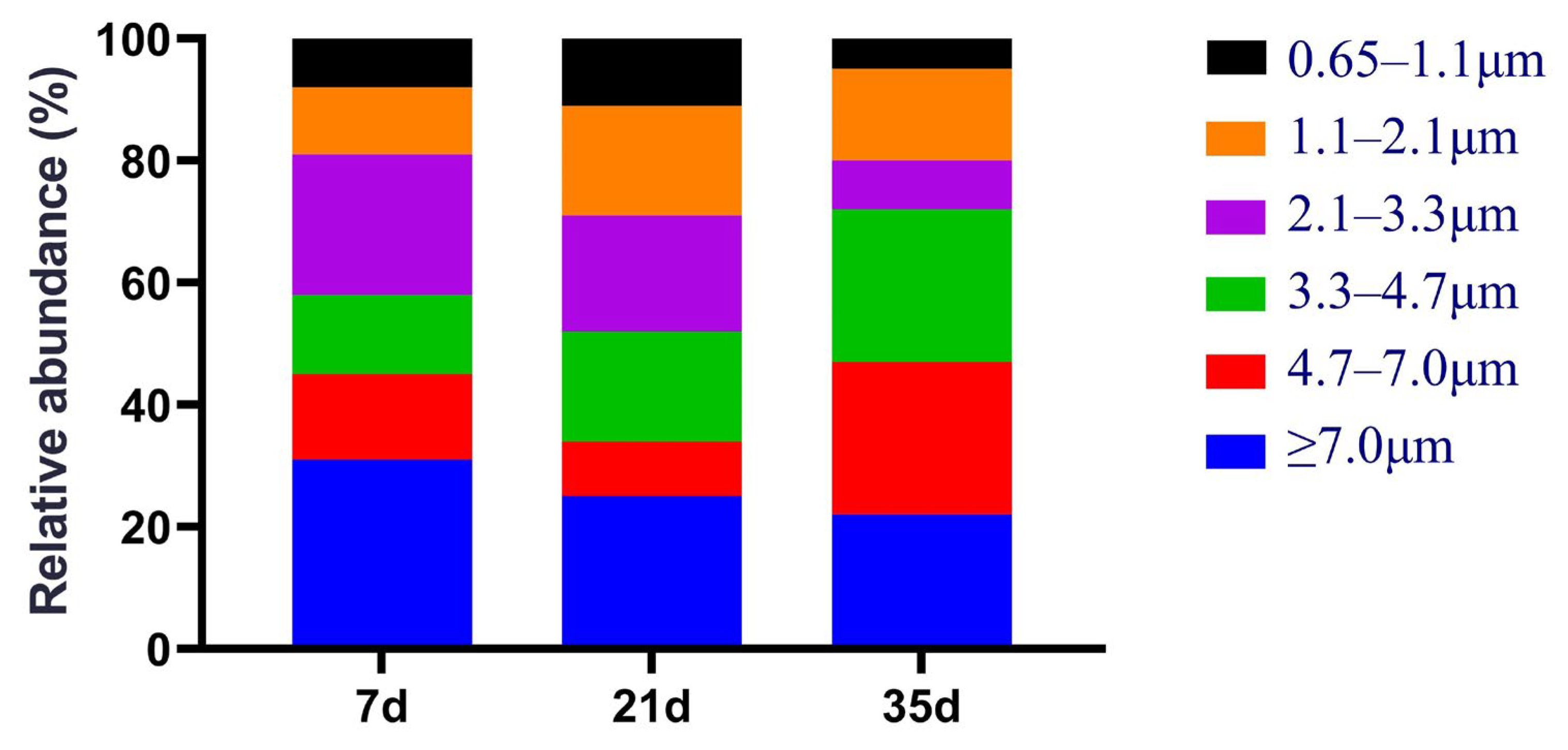

3.1. Concentration and Size Distribution of Colony Fungal Bioaerosols in Broiler Houses

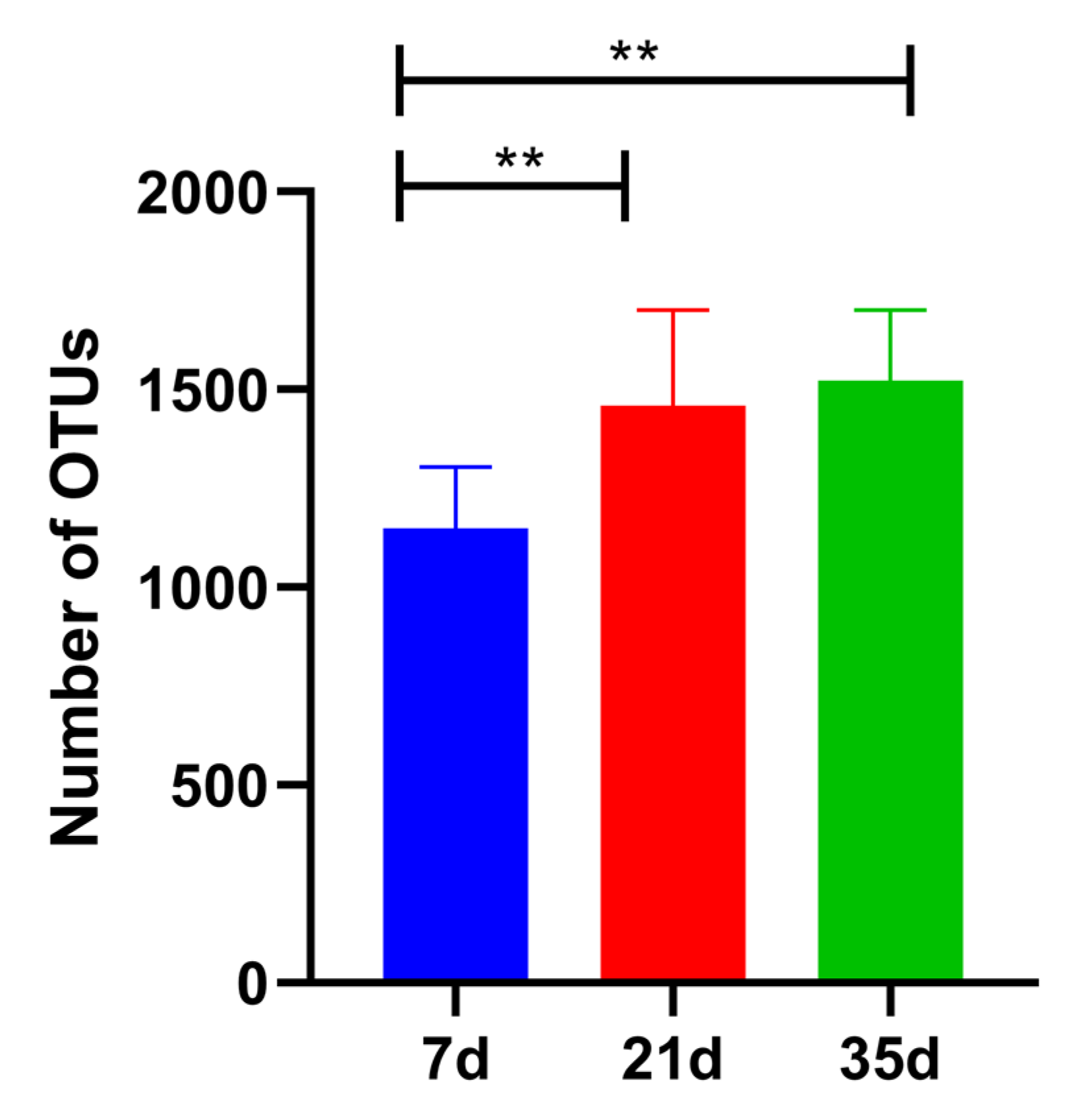

3.2. Fungal Community Analysis Based on ITS Gene Sequencing

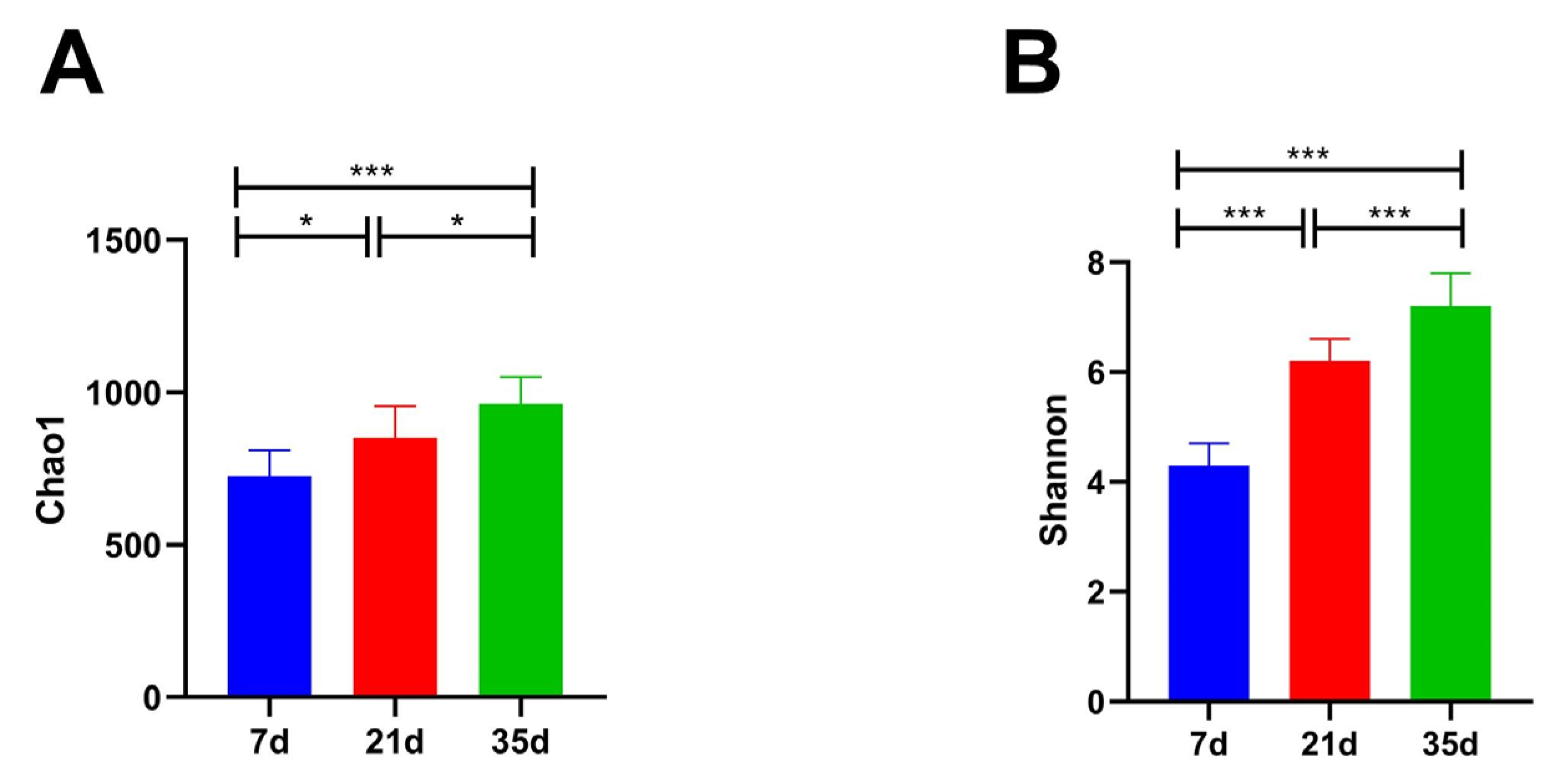

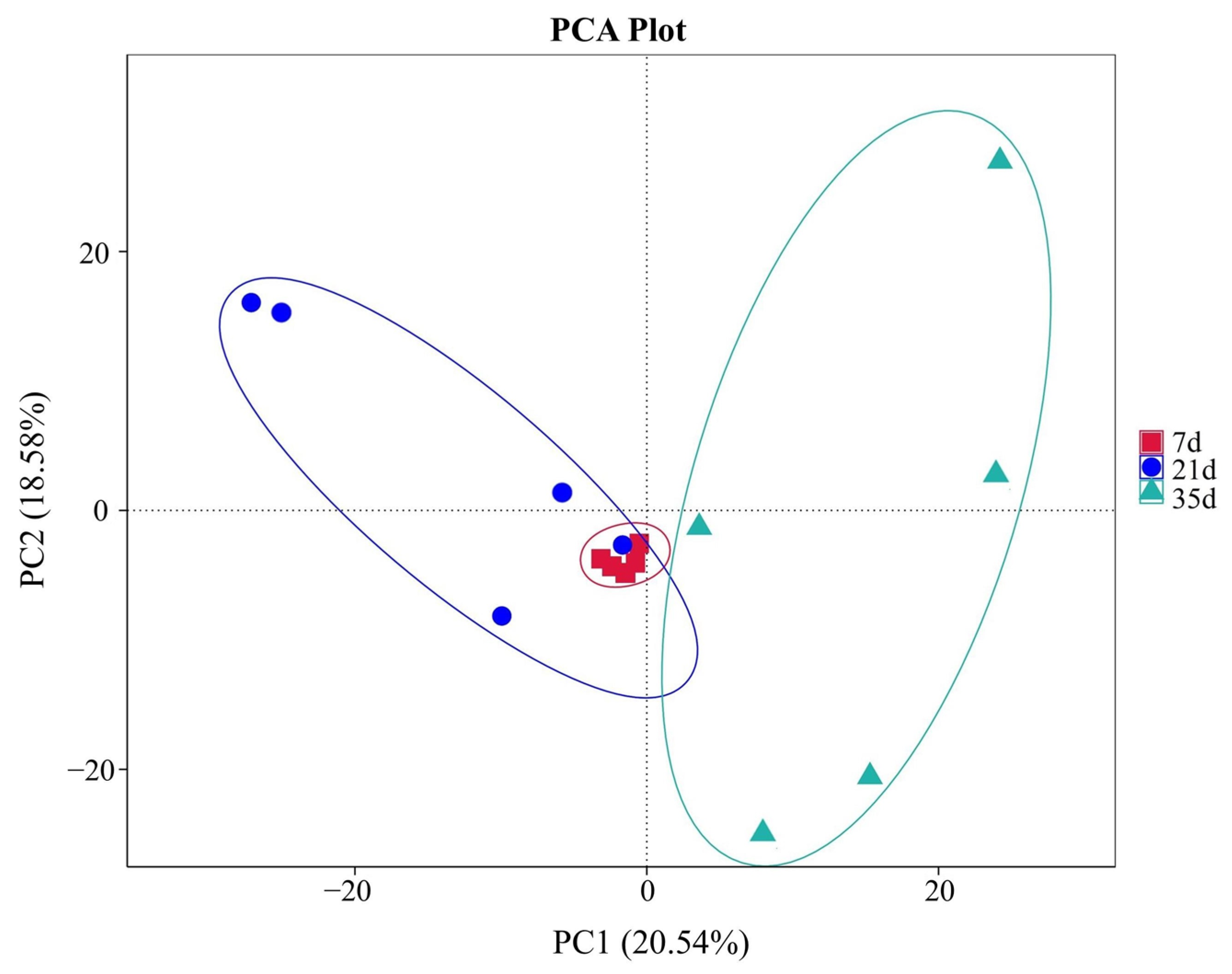

3.3. Fungal Community Diversity Analysis

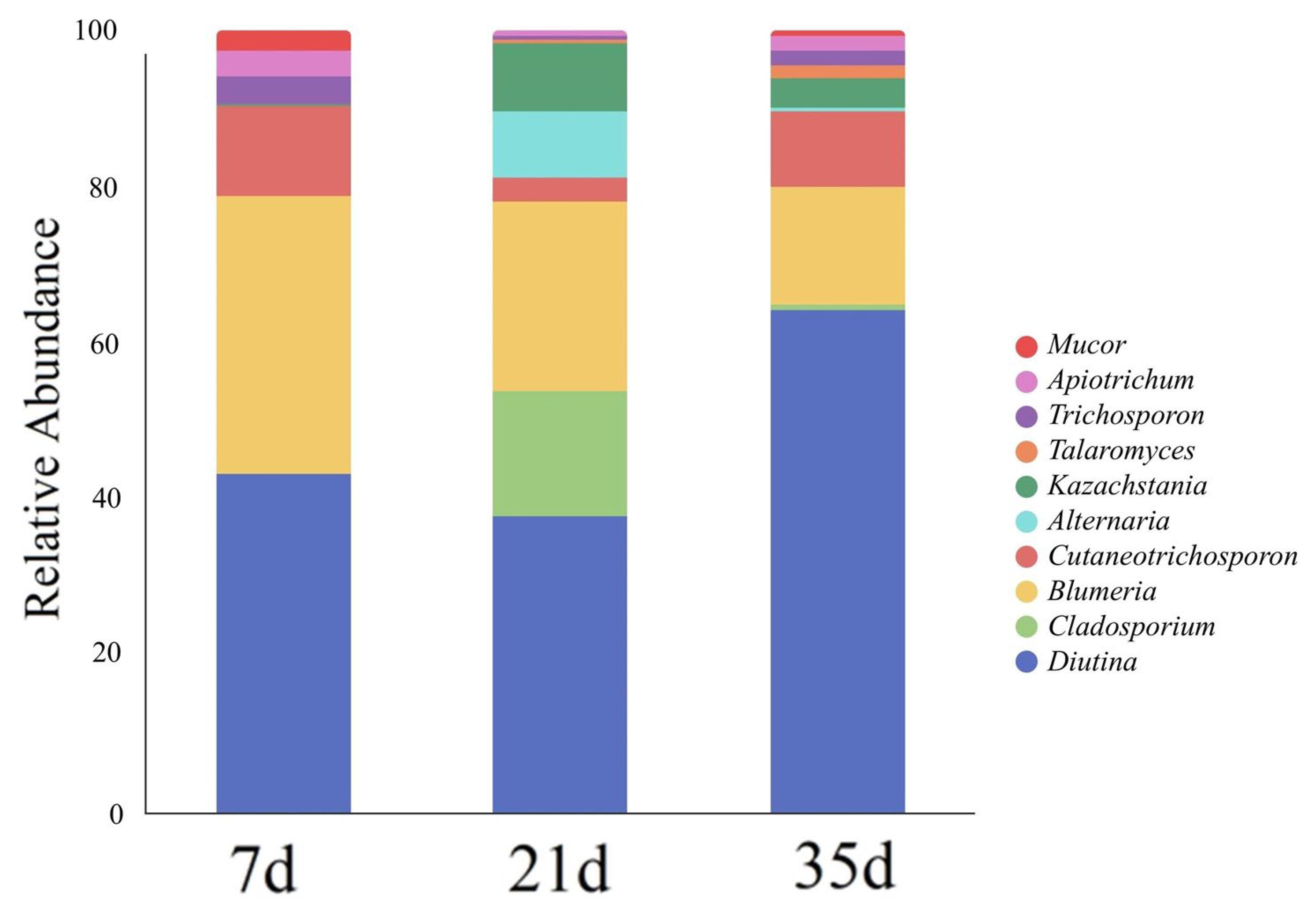

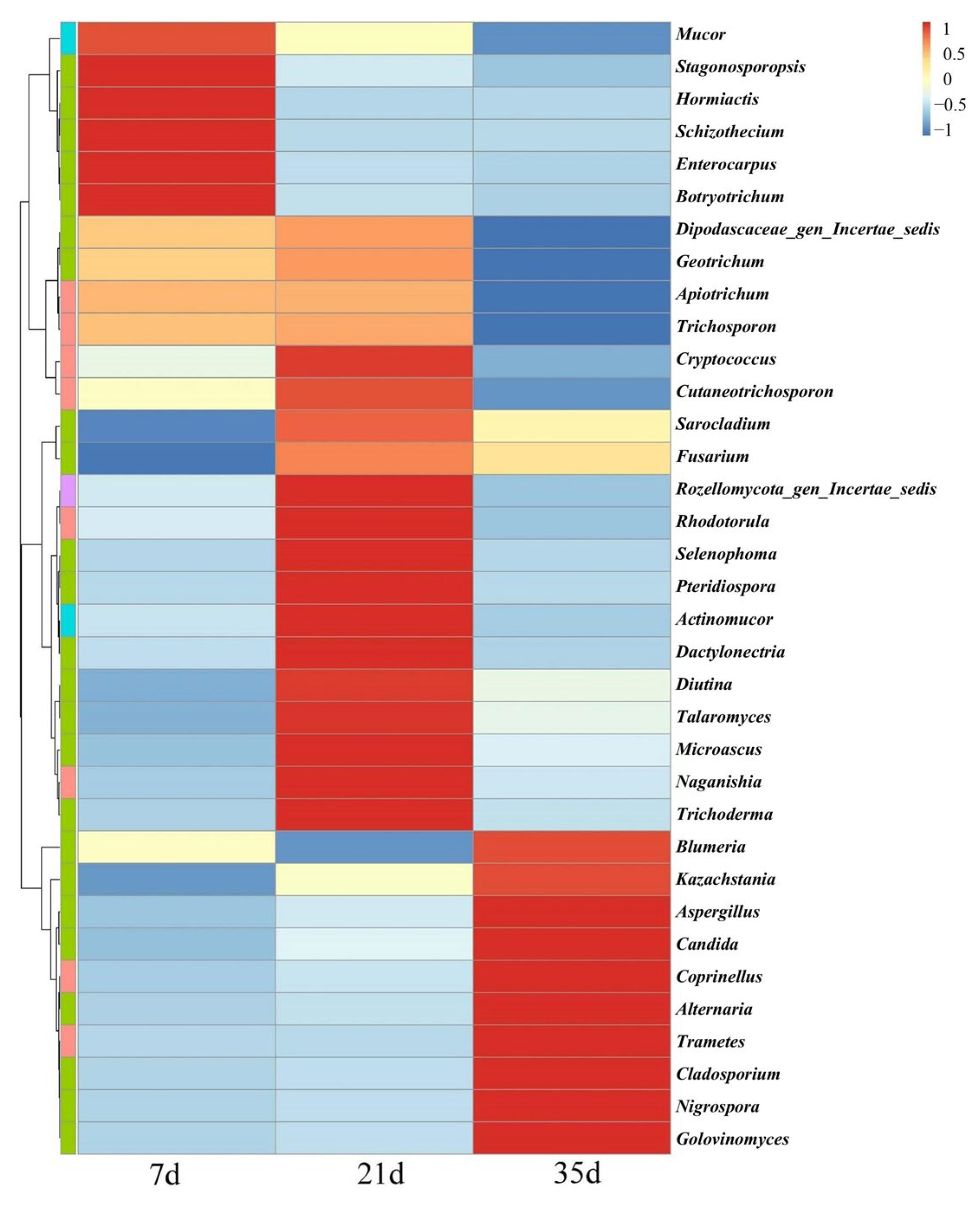

3.4. Fungal Community Composition and Succession Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gomes, B.; Dias, M.; Cervantes, R.; Pena, P.; Santos, J.; Pinto, M.V.; Viegas, C. One health approach to tackle microbial contamination on poultries—A systematic review. Toxics 2023, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, B.; Rasool, K.; Siddique, A.; Jabbar, K.A.; El-Malaha, S.S.; Sohail, M.U.; Almomani, F.; Alfarra, M.R. Size-resolved ambient bioaerosols concentration, antibiotic resistance, and community composition during autumn and winter seasons in qatar. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Yang, G.; Cai, Y.; Yu, G. Bacterial and fungal aerosols in poultry houses: PM(2.5) metagenomics via single-molecule real-time sequencing. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Sun, X.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, T.; Xin, H.; Yu, A.; Wang, X.; Gao, M. Particle-size stratification of airborne antibiotic resistant genes, mobile genetic elements, and bacterial pathogens within layer and broiler farms in Beijing, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 112799–112812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Germain, M.-W.; Létourneau, V.; Cruaud, P.; Lemaille, C.; Robitaille, K.; Denis, É.; Boulianne, M.; Duchaine, C. Longitudinal survey of total airborne bacterial and archaeal concentrations and bacterial diversity in enriched colony housing and aviaries for laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, N.; Tsameret, S.; Gaire, T.N.; Mendoza, K.M.; Cortus, E.L.; Cardona, C.; Noyes, N.; Li, J. Influence of rainfall on size-resolved bioaerosols around a livestock farm. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielowiec-Korzeniowska, A.; Trawińska, B.; Tymczyna, L.; Bis-Wencel, H.; Matuszewski, Ł. Microbial contamination of the air in livestock buildings as a threat to human and animal health—A review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2021, 21, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, W.; Xie, C.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, W.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, H. Airborne bacterial communities in the poultry farm and their relevance with environmental factors and antibiotic resistance genes. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 846, 157420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannaa, M.; Kim, K.D. Effect of temperature and relative humidity on growth of aspergillus and penicillium spp. and biocontrol activity of pseudomonas protegens as15 against aflatoxigenic aspergillus flavus in stored rice grains. Mycobiology 2018, 46, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saeed, B.A.; Elshebrawy, H.A.; Zakaria, A.I.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Imre, K.; Morar, A.; Herman, V.; Sallam, K.I. Multidrug-resistant proteus mirabilis and other gram-negative species isolated from native egyptian chicken carcasses. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, C. One health: A holistic approach for food safety in livestock. Sci. One Health 2022, 1, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuhanna, E.; Ahmed, A.; Al-Yousif, Y. Effect of air contaminants on poultry immunological and production performance. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2011, 10, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ma, D.; Huang, Q.; Tang, W.; Wei, M.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, H.; Yu, X.; Zheng, W.; et al. Aerosol concentrations and fungal communities within broiler houses in different broiler growth stages in summer. Front. Veter-Sci. 2021, 8, 775502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Ying, S.; Xiang, R. Spatial analysis of airborne bacterial concentrations and microbial communities in a large-scale commercial layer facility. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Yang, L.; Yang, C.; Dominy, R.; Hu, C.; Du, H.; Li, Q.; Yu, C.; Xie, L.; Jiang, X. Investigation of bio-aerosol dispersion in a tunnel-ventilated poultry house. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 167, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatawah, Q.A.; Al-Khalaifah, H.S.; Aldameer, A.S.; Ali, A.K.; Benhaji, A.H.; Varghese, J.S. Microbiological indoor and outdoor air quality in chicken fattening houses. J. Environ. Public Health 2023, 2023, 3512328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovanh, N.; Cook, K.L.; Rothrock, M.J.; Miles, D.M.; Sistani, K. Spatial shifts in microbial population structure within poultry litter associated with physicochemical properties. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 1840–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, N.; Furneaux, B.; Hardwick, B.; Somervuo, P.; Palorinne, I.; Aguilar-Trigueros, C.A.; Andrew, N.R.; Babiy, U.V.; Bao, T.; Bazzano, G.; et al. Airborne DNA reveals predictable spatial and seasonal dynamics of fungi. Nature 2024, 631, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraïs, S.; Winkler, S.; Zorea, A.; Levin, L.; Nagies, F.S.P.; Kapust, N.; Lamed, E.; Artan-Furman, A.; Bolam, D.N.; Yadav, M.P.; et al. Cryptic diversity of cellulose-degrading gut bacteria in industrialized humans. Science 2024, 383, eadj9223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.; Manrique, A.; Sabo-Attwood, T.; Coker, E.S. A narrative review of occupational air pollution and respiratory health in farmworkers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villena, J.F.; Vargas, D.A.; López, R.B.; Chávez-Velado, D.R.; Casas, D.E.; Jiménez, R.L.; Sanchez-Plata, M.X. Bio-mapping indicators and pathogen loads in a commercial broiler processing facility operating with high and low antimicrobial intervention levels. Foods 2022, 11, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastuszka, J.S.; Paw, U.K.T.; Lis, D.O.; Wlazło, A.; Ulfig, K. Bacterial and fungal aerosol in indoor environment in Upper Silesia, Poland. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 3833–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cui, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Feng, W.; Liu, Z.; Yan, M.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, R.; Yang, Y.; et al. Ecological succession of airborne bacterial aerosols in poultry houses: Insights from taihang chickens. Animals 2025, 15, 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. Distribution of aerosol bacteria in broiler houses at different growth stages during winter. Animals 2025, 15, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möller, E.; Bahnweg, G.; Sandermann, H.; Geiger, H. A simple and efficient protocol for isolation of high molecular weight DNA from filamentous fungi, fruit bodies, and infected plant tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20, 6115–6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. Its primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostović, M.; Ravić, I.; Kovačić, M.; Kabalin, A.E.; Matković, K.; Sabolek, I.; Pavičić, Ž.; Menčik, S.; Tomić, D.H. Differences in fungal contamination of broiler litter between summer and winter fattening periods. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2021, 72, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yan, H.; Xiu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, G.; Yu, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Seasonal dynamics in bacterial communities of closed-cage broiler houses. Front. Veter-Sci. 2022, 9, 1019005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.; Malta-Vacas, J.; Sabino, R.; Viegas, S.; Veríssimo, C. Accessing indoor fungal contamination using conventional and molecular methods in portuguese poultries. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Chen, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, G.; Yu, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Tang, W.; et al. Spatial distribution of airborne bacterial communities in caged poultry houses. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2023, 73, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secondo, L.E.; Sagona, J.A.; Calderón, L.; Wang, Z.; Plotnik, D.; Senick, J.; Sorensen-Allacci, M.; Wener, R.; Andrews, C.J.; Mainelis, G. Estimating lung deposition of fungal spores using actual airborne spore concentrations and physiological data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 1852–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, K.; He, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yun, Y.; Sang, N. Diel variations of airborne microbes and antibiotic resistance genes in response to urban PM(2.5) chemical properties during the heating season. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 352, 124120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, C.; Yang, L.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiong, X.; Peng, H.; Chen, J.; et al. Aerosol dynamics in the respiratory tract of food-producing animals: An insight into transmission patterns and deposition distribution. Animals 2025, 15, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, E.; Poothong, S.; Koekkoek, J.; Lucattini, L.; Padilla-Sánchez, J.A.; Haugen, M.; Herzke, D.; Valdersnes, S.; Maage, A.; Cousins, I.T.; et al. Estimating human exposure to perfluoroalkyl acids via solid food and drinks: Implementation and comparison of different dietary assessment methods. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Denning, D.W. The WHO fungal priority pathogens list as a game-changer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Ghany, W. Avian aspergillosis: A potential occupational zoonotic mycosis especially in Egypt. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2021, 9, 1564–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, F.; Salem, E. Respiratory health disorders associated with occupational exposure to bioaerosols among workers in poultry breeding farms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 19869–19876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.-J.; Li, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-H.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Ruan, S.-M.; Jiang, B.-G.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Y.-S.; Wang, L.-P.; Liu, W.; et al. Short-term exposure to ambient air pollution and influenza: A multicity study in China. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 127010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, K.J. The microevolution of antifungal drug resistance in pathogenic fungi. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, E.B. A comprehensive longitudinal study of gut microbiota dynamic changes in laying hens at four growth stages prior to egg production. Anim. Biosci. 2023, 36, 1727–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, D.H.; Ravić, I.; Kabalin, A.E.; Kovačić, M.; Gottstein, Ž.; Ostović, M. Effects of season and house microclimate on fungal flora in air and broiler trachea. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ren, Z.; Feng, W.; Li, Z.; Lu, Y.; Yan, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, R.; Liu, M.; et al. Fungal aerosol exposure and stage-specific variations in taihang chicken houses during winter. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, X.; Cheng, S.; et al. Dynamics and Health Risks of Fungal Bioaerosols in Confined Broiler Houses During Winter. Animals 2026, 16, 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030437

Yan M, Liu Z, Liu M, Liu H, Li Z, Yang Z, Lu Y, Feng W, Chen X, Cheng S, et al. Dynamics and Health Risks of Fungal Bioaerosols in Confined Broiler Houses During Winter. Animals. 2026; 16(3):437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030437

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Mengxi, Zhuhua Liu, Mingli Liu, Huage Liu, Zhenyue Li, Zitong Yang, Yi Lu, Wenhao Feng, Xiaolong Chen, Shuang Cheng, and et al. 2026. "Dynamics and Health Risks of Fungal Bioaerosols in Confined Broiler Houses During Winter" Animals 16, no. 3: 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030437

APA StyleYan, M., Liu, Z., Liu, M., Liu, H., Li, Z., Yang, Z., Lu, Y., Feng, W., Chen, X., Cheng, S., Yang, Y., Zhang, C., Wang, X., & Cui, H. (2026). Dynamics and Health Risks of Fungal Bioaerosols in Confined Broiler Houses During Winter. Animals, 16(3), 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030437