Identifying the Genetic Basis of Fetal Loss in Cows and Heifers Through a Genome-Wide Association Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Phenotypes

2.2. Genotyping and Imputation

2.3. Genotyping Quality Control

2.4. Genome-Wide Association Analysis

2.5. Identification of Population Stratification

2.6. Proportion of Variance Explained

2.7. Estimation of Heritability

2.8. Positional Candidate Genes

2.9. Loci Reported in Previous Fertility Studies

2.10. Comparison of Loci Associated with Fetal Loss and Production Traits

3. Results and Discussion

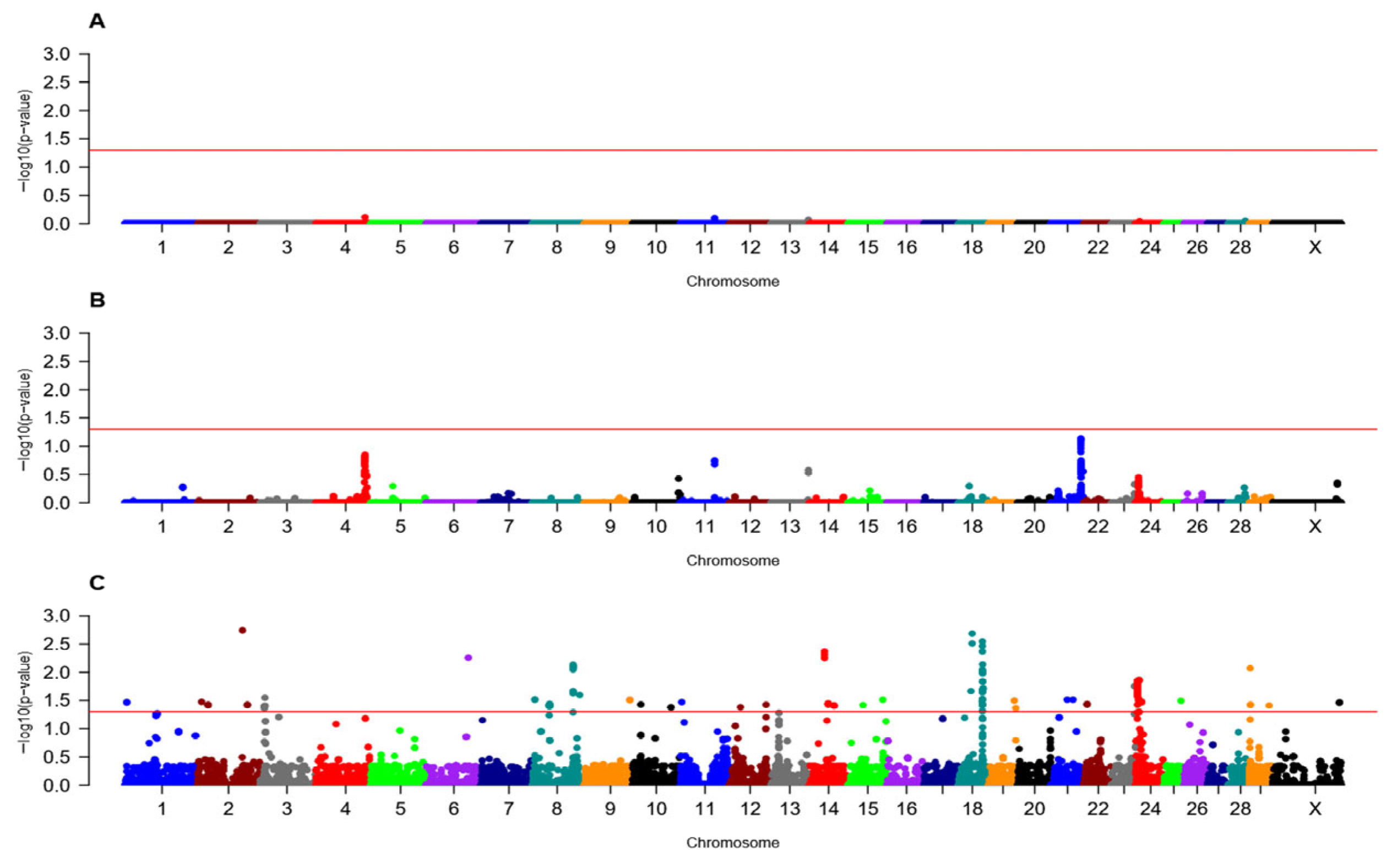

3.1. Loci Associated with Fetal Loss in Heifers

3.2. Loci Associated with Fetal Loss in Primiparous Cows

3.3. Loci Associated with Fetal Loss That Are Shared with Production Traits

3.4. Recessive Inheritance of Fetal Loss

3.5. Estimated Heritability of Fetal Loss

3.6. Comparison of Loci Associated with Fetal Loss in Heifers and Primiparous Cows

3.7. Comparison of Loci Associated with Fetal Loss and Other Fertility Traits

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial insemination |

| AI-REML | Average information restricted maximum likelihood |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| Bp | Base pairs |

| BTA | Bos taurus chromosome |

| CR | Conception rate |

| D’ | Standardized disequilibrium coefficient |

| DPR | Daughter pregnancy rate |

| EMMAX | Efficient mixed model association eXpedited |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GBLUP | Genomic linear unbiased predictor |

| GWAA | Genome-wide association analysis |

| HCR1 | Heifer conception rate at first service |

| Kb | Kilobase |

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium |

| LPL | Length of productive life |

| Mb | Megabase |

| p | p value |

| PCG | Positional candidate gene |

| Pos | Position |

| PR | Pregnancy rate |

| PVE | Proportion of variance explained |

| QTL | Quantitative trait locus |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| SA | Spontaneous abortion or fetal loss |

| SVS | SNP and variation suite |

| TBRD | Number of times bred by artificial insemination before a pregnancy was achieved |

| λGC | Genomic inflation factor |

References

- Andrade, M.F.; Simões, J. Embryonic and Fetal Mortality in Dairy Cows: Incidence, Relevance, and Diagnosis Approach in Field Conditions. Dairy 2024, 5, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Kang, S.-S.; Won, J.I.; Kim, H.J.; Jang, S.S.; Kim, S.W. Analyzing Environmental Factors Influencing the Gestation Length and Birth Weight of Hanwoo Cattle. J. Anim. Reprod. Biotechnol. 2024, 39, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, S.I.; Buckley, F.; Ilatsia, E.D.; Berry, D.P. Gestation Length and Its Associations with Calf Birth Weight, Calf Perinatal Mortality, and Dystocia in Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 8685–8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szenci, O. Recent Possibilities for the Diagnosis of Early Pregnancy and Embryonic Mortality in Dairy Cows. Animals 2021, 11, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigdel, A.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Peñagaricano, F. Genes and Pathways Associated with Pregnancy Loss in Dairy Cattle. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.M.; Burato, S.; Neira, L.; Harvey, K.; Menegatti Zoca, S.; Mercadante, V.R.G.; Fontes, P.L.P. Impact of Late Embryonic and Early Fetal Mortality on Productivity of Beef Cows. Trans. Anim. Sci. 2025, 9, txaf071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigdel, A.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Peñagaricano, F. Genetic Analysis of Fetal Loss in Holstein Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9012–9020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltbank, M.C.; Baez, G.M.; Garcia-Guerra, A.; Toledo, M.Z.; Monteiro, P.L.J.; Melo, L.F.; Ochoa, J.C.; Santos, J.E.P.; Sartori, R. Pivotal Periods for Pregnancy Loss during the First Trimester of Gestation in Lactating Dairy Cows. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teja, A.; Sarkar, D.; Rahman, M.; Kumar, M.P.; Chandana, B.; Varma, C.G.; RaviKumar, M. Early Embryonic Mortality in Cattle and It’s Preventive Strategies: A Review. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husb. 2024, 9, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, K.; Chasco, A.; Pacheco, H.; Sigdel, A.; Guinan, F.; Lauber, M.; Fricke, P.; Peñagaricano, F. Genomic Selection in Dairy Cattle: Impact and Contribution to the Improvement of Bovine Fertility. Clin. Theriogenol. 2024, 16, 10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humblot, P. Use of Pregnancy Specific Proteins and Progesterone Assays to Monitor Pregnancy and Determine the Timing, Frequencies and Sources of Embryonic Mortality in Ruminants. Theriogenology 2001, 56, 1417–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.F.; Wahl, A.M.; Dick, M.; Toenges, J.A.; Kiser, J.N.; Galliou, J.M.; Moraes, J.G.N.; Burns, G.W.; Dalton, J.; Spencer, T.E.; et al. Genomic Analysis of Spontaneous Abortion in Holstein Heifers and Primiparous Cows. Genes 2019, 10, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, B.; Kindinger, L.; Mahindra, M.P.; Moatti, Z.; Siassakos, D. Stillbirth: Prevention and Supportive Bereavement Care. BMJ Med. 2023, 2, e000262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.E.P.; Thatcher, W.W.; Chebel, R.C.; Cerri, R.L.A.; Galvão, K.N. The Effect of Embryonic Death Rates in Cattle on the Efficacy of Estrus Synchronization Programs. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2004, 82–83, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, C.T.; Lean, I.J.; Garvin, J.K. Factors Influencing Fertility of Holstein Dairy Cows: A Multivariate Description. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 3225–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismael, A.; Strandberg, E.; Berglund, B.; Fogh, A.; Løvendahl, P. Seasonality of Fertility Measured by Physical Activity Traits in Holstein Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2837–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, J.E.; Royal, M.D.; Garnsworthy, P.C.; Mao, I.L. Fertility in the High-Producing Dairy Cow. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2004, 86, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mee, J. Reproductive Issues Arising from Different Management Systems in the Dairy Industry. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Guldbrandtsen, B.; Lund, M.S.; Sahana, G. Prioritizing Candidate Genes for Fertility in Dairy Cows Using Gene-Based Analysis, Functional Annotation and Differential Gene Expression. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrzecińska, M.; Czerniawska-Piątkowska, E.; Kowalczyk, A. The Impact of Stress and Selected Environmental Factors on Cows’ Reproduction. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2021, 49, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzeraa, L.; Martin, H.; Dufour, P.; Marques, J.C.S.; Cerri, R.; Sirard, M.-A. Epigenetic Insights into Fertility: Involvement of Immune Cell Methylation in Dairy Cows Reproduction. Biol. Reprod. 2025, ioaf020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneda, M.M.; Costa, C.B.; Zangirolamo, A.F.; Anjos, M.M.D.; Paula, G.R.D.; Morotti, F. From the Laboratory to the Field: How to Mitigate Pregnancy Losses in Embryo Transfer Programs? Anim. Reprod. 2024, 21, e20240032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.S. Identification of Genes Associated with Reproductive Function in Dairy Cattle. Anim. Reprod. 2018, 15, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catrett, C.C.; Moorey, S.E.; Beever, J.E.; Rowan, T.N. Quantifying Phenotypic and Genetic Variation for Cow Fertility Phenotypes in American Simmental Using Total Herd Reporting Data. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelson, V.C.; Kiser, J.N.; Davenport, K.M.; Suarez, E.M.; Murdoch, B.M.; Neibergs, H.L. Genomic Regions Associated with Embryonic Loss in Primiparous Holstein Cows. Front. Anim. Sci. 2024, 5, 1458088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelson, V.; Kiser, J.; Davenport, K.; Suarez, E.; Murdoch, B.; Neibergs, H. Genomic Regions Associated with Holstein Heifer Times Bred to Artificial Insemination and Embryo Transfer Services. Genomics 2025, 117, 110972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Shadparvar, A.A.; Baneh, H.; Ghovvati, S. Genome-Wide Scanning for Candidate Lethal Genes Associated with Early Embryonic Mortality in Holstein Dairy Cattle. Front. Anim. Sci. 2025, 6, 1513876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, E.M.; Kelson, V.C.; Kiser, J.N.; Davenport, K.M.; Murdoch, B.M.; Neibergs, H.L. Genomic Regions Associated with Spontaneous Abortion in Holstein Heifers. Genes 2024, 15, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, E.M.; Kelson, V.C.; Kiser, J.N.; Davenport, K.M.; Murdoch, B.M.; Herrick, A.L.; Neibergs, H.L. Loci Associated with Spontaneous Abortion in Primiparous Holstein Cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1599401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaglen, S.A.E.; Bijma, P. Genetic Parameters of Direct and Maternal Effects for Calving Ease in Dutch Holstein-Friesian Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 2229–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, A.J.; Meyre, D. Assessing the Heritability of Complex Traits in Humans: Methodological Challenges and Opportunities. Curr. Genom. 2017, 18, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele Lombebo, W.; Kang, H.; Mingxin, D.; Tesema Wondie, Z.; Mekuriaw Tarekegn, G.; Zheng, H. Genetic Parameter Estimates and Genetic Trends for Reproductive Traits of Holstein Dairy Cattle in China. J. Dairy Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Recio, O.; López de Maturana, E.; Gutiérrez, J.P. Inbreeding Depression on Female Fertility and Calving Ease in Spanish Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 5744–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryce, J.E.; Haile-Mariam, M.; Goddard, M.E.; Hayes, B.J. Identification of Genomic Regions Associated with Inbreeding Depression in Holstein and Jersey Dairy Cattle. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2014, 46, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Reinoso, M.A.; Aponte, P.M.; Cabezas, J.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L.; Garcia-Herreros, M. Genomic Evaluation of Primiparous High-Producing Dairy Cows: Inbreeding Effects on Genotypic and Phenotypic Production–Reproductive Traits. Animals 2020, 10, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Reinoso, M.A.; Aponte, P.M.; García-Herreros, M. A Review of Inbreeding Depression in Dairy Cattle: Current Status, Emerging Control Strategies, and Future Prospects. J. Dairy Res. 2022, 89, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranger, B.E.; Stahl, E.A.; Raj, T. Progress and Promise of Genome-Wide Association Studies for Human Complex Trait Genetics. Genetics 2011, 187, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M.; Bossé, Y.; Paré, G.; Meyre, D. Benefits and Limitations of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laisk, T.; Soares, A.L.G.; Ferreira, T.; Painter, J.N.; Censin, J.C.; Laber, S.; Bacelis, J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lepamets, M.; Lin, K.; et al. The Genetic Architecture of Sporadic and Multiple Consecutive Miscarriage. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, P.A.S.; Schenkel, F.S.; Cánovas, A. Genome-Wide Association Study Using Haplotype Libraries and Repeated-Measures Model to Identify Candidate Genomic Regions for Stillbirth in Holstein Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 1314–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoso, A.; Nandakumar, P.; Shi, J.; Bielenberg, J.; 23andMe Research Team; Holmes, M.V.; Aslibekyan, S. Trans-Ancestral Genome Wide Association Study of Sporadic and Recurrent Miscarriage. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, M.; García, J.E.; Véliz Deras, F.G.; de los Santiago, M.Á.; Mellado, J.; Gaytán, L.R.; Ángel-García, O.; Mellado, M.; García, J.E.; Véliz Deras, F.G.; et al. The Effects of Periparturient Events, Mastitis, Lameness and Ketosis on Reproductive Performance of Holstein Cows in a Hot Environment. Austral J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawneh, J.I.; Laven, R.A.; Stevenson, M.A. The Effect of Lameness on the Fertility of Dairy Cattle in a Seasonally Breeding Pasture-Based System. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5487–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.R.; Peñagaricano, F.; Santos, J.E.P.; DeVries, T.J.; McBride, B.W.; Ribeiro, E.S. Long-Term Effects of Postpartum Clinical Disease on Milk Production, Reproduction, and Culling of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 11701–11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.O. Symposium Review: Mechanisms of Disruption of Fertility by Infectious Diseases of the Reproductive Tract. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3754–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammad, A.; Khan, M.Z.; Abbas, Z.; Hu, L.; Ullah, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y. Major Nutritional Metabolic Alterations Influencing the Reproductive System of Postpartum Dairy Cows. Metabolites 2022, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, B.L.; Browning, S.R. Genotype Imputation with Millions of Reference Samples. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The Variant Call Format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.M.; Sul, J.H.; Service, S.K.; Zaitlen, N.A.; Kong, S.; Freimer, N.B.; Sabatti, C.; Eskin, E. Variance Component Model to Account for Sample Structure in Genome-Wide Association Studies. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.M. Genetic Association Studies: Design, Analysis and Interpretation. Brief. Bioinform. 2002, 3, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setu, T.J.; Basak, T. An Introduction to Basic Statistical Models in Genetics. Open J. Stat. 2021, 11, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otowa, T.; Maher, B.S.; Aggen, S.H.; McClay, J.L.; van den Oord, E.J.; Hettema, J.M. Genome-Wide and Gene-Based Association Studies of Anxiety Disorders in European and African American Samples. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewontin, R.C. The Interaction of Selection and Linkage. I. General Considerations; Heterotic Models. Genetics 1964, 49, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, K.M.; Clark, A.G. Linkage Disequilibrium and the Mapping of Complex Human Traits. Trends Genet. 2002, 18, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliou, J.M.; Kiser, J.N.; Oliver, K.F.; Seabury, C.M.; Moraes, J.G.N.; Burns, G.W.; Spencer, T.E.; Dalton, J.; Neibergs, H.L. Identification of Loci and Pathways Associated with Heifer Conception Rate in U.S. Holsteins. Genes 2020, 11, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohmanova, J.; Sargolzaei, M.; Schenkel, F.S. Characteristics of Linkage Disequilibrium in North American Holsteins. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing v. 4.5.1.; Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Devlin, B.; Roeder, K. Genomic Control for Association Studies. Biometrics 1999, 55, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiopoulos, G.; Evangelou, E. Power Considerations for λ Inflation Factor in Meta-Analyses of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Genet. Res. 2016, 98, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, V.; Vilhjálmsson, B.J.; Platt, A.; Korte, A.; Seren, Ü.; Long, Q.; Nordborg, M. An Efficient Multi-Locus Mixed-Model Approach for Genome-Wide Association Studies in Structured Populations. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhjálmsson, B.J.; Nordborg, M. The Nature of Confounding in Genome-Wide Association Studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanRaden, P.M. Efficient Methods to Compute Genomic Predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 4414–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.F. Implementation and Accuracy of Genomic Selection. Aquaculture 2014, 420–421, S8–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandén, I.; Mäntysaari, E.A.; Lidauer, M.H.; Thompson, R.; Gao, H. A Computationally Efficient Algorithm to Leverage Average Information REML for (Co)Variance Component Estimation in the Genomic Era. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2024, 56, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.B.; Schaffner, S.F.; Nguyen, H.; Moore, J.M.; Roy, J.; Blumenstiel, B.; Higgins, J.; DeFelice, M.; Lochner, A.; Faggart, M.; et al. The Structure of Haplotype Blocks in the Human Genome. Science 2002, 296, 2225–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.-L.; Fritz, E.R.; Reecy, J.M. AnimalQTLdb: A Livestock QTL Database Tool Set for Positional QTL Information Mining and Beyond. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D604–D609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-L.; Park, C.A.; Reecy, J.M. Bringing the Animal QTLdb and CorrDB into the Future: Meeting New Challenges and Providing Updated Services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D956–D961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker Gaddis, K.L.; Null, D.J.; Cole, J.B. Explorations in Genome-Wide Association Studies and Network Analyses with Dairy Cattle Fertility Traits. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 6420–6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, J.N.; Clancey, E.; Moraes, J.G.N.; Dalton, J.; Burns, G.W.; Spencer, T.E.; Neibergs, H.L. Identification of Loci Associated with Conception Rate in Primiparous Holstein Cows. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaneld, T.G.; Kuehn, L.A.; Thomas, M.G.; Snelling, W.M.; Smith, T.P.L.; Pollak, E.J.; Cole, J.B.; Keele, J.W. Genomewide Association Study of Reproductive Efficiency in Female Cattle1,2,3,4. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 1945–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.B.; Wiggans, G.R.; Ma, L.; Sonstegard, T.S.; Lawlor, T.J.; Crooker, B.A.; Van Tassell, C.P.; Yang, J.; Wang, S.; Matukumalli, L.K.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Thirty One Production, Health, Reproduction and Body Conformation Traits in Contemporary U.S. Holstein Cows. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglund, J.K.; Sahana, G.; Guldbrandtsen, B.; Lund, M.S. Validation of Associations for Female Fertility Traits in Nordic Holstein, Nordic Red and Jersey Dairy Cattle. BMC Genet. 2014, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Sun, L.; Xie, X.; Yao, X.; Tian, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, F.; Liu, J. TMEM225 Is Essential for Sperm Maturation and Male Fertility by Modifying Protein Distribution of Sperm in Mice. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2024, 23, 100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, K.M.; O’Neil, E.V.; Ortega, M.S.; Patterson, A.; Kelleher, A.M.; Warren, W.C.; Spencer, T.E. Single-Cell Insights into Development of the Bovine Placenta. Biol. Reprod. 2024, 110, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhra, G.; Rakhra, G. Zinc Finger Proteins: Insights into the Transcriptional and Post Transcriptional Regulation of Immune Response. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 5735–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.; Lazaridis, A.; Grammatis, A.; Hirsch, M. The Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Infertility. Curr. Opin. Obs. Gynecol. 2022, 34, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpova, N.; Dmitrenko, O.; Nurbekov, M. Polymorphism Rs259983 of the Zinc Finger Protein 831 Gene Increases Risk of Superimposed Preeclampsia in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabath, K.; Jonas, S. Take a Break: Transcription Regulation and RNA Processing by the Integrator Complex. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2022, 77, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razew, M.; Fraudeau, A.; Pfleiderer, M.M.; Linares, R.; Galej, W.P. Structural Basis of the Integrator Complex Assembly and Association with Transcription Factors. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 2542–2552.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalpour, S.; Zain, S.M.; Vazifehmand, R.; Mohamed, Z.; Pung, Y.F.; Kamyab, H.; Omar, S.Z. Analysis of Serum Circulating MicroRNAs Level in Malaysian Patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Role of microRNAs in Embryo Implantation. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2017, 15, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico-Sordo, L.; García-Velasco, J.A. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets in Female Infertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmann, H.; Kiesel, L. The Role of miRNA in Endometriosis-Related Infertility—An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberianpour, S.; Abkhooie, L. MiR-1307: A Comprehensive Review of Its Role in Various Cancer. Gene Rep. 2021, 25, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jia, Q.; Xi, J.; Zhou, B.; Li, Z. Integrated Analysis of lncRNA, miRNA and mRNA Reveals Novel Insights into the Fertility Regulation of Large White Sows. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A Review of Programmed Cell Death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haanen, C.; Vermes, I. Apoptosis: Programmed Cell Death in Fetal Development. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1996, 64, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, H.M.; Valadão, L.I.; da Silva, F.M. Apoptosis as the Major Cause of Embryonic Mortality in Cattle. In New Insights into Theriogenology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Molchadsky, A.; Rivlin, N.; Brosh, R.; Rotter, V.; Sarig, R. P53 Is Balancing Development, Differentiation and de-Differentiation to Assure Cancer Prevention. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, M.H.; He, Y.; Huang, J. Embryonic Stem Cells Shed New Light on the Developmental Roles of P53. Cell Biosci. 2013, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Xu, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liao, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Mei, X.; et al. Programmed Cell Death 11 Modulates but Not Entirely Relies on P53-HDM2 Loop to Facilitate G2/M Transition in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Oncogenesis 2023, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, G.; Yan, H.; Malik, N.; Huang, J. An Updated View of the Roles of P53 in Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2022, 40, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Arenas, A.; Piña-Medina, A.G.; González-Flores, O.; Galván-Rosas, A.; Porfirio, G.A.; Camacho-Arroyo, I. Sex Hormones and Expression Pattern of Cytoskeletal Proteins in the Rat Brain throughout Pregnancy. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 139, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.K.; Guan, Y.-L.; Shi, S.-R. MAP2 Expression in Developing Dendrites of Human Brainstem Auditory Neurons. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1998, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, J.E.; Jacobson, M.; Kosik, K.S. Ontogenesis of Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 (MAP2) in Embryonic Mouse Cortex. Dev. Brain Res. 1986, 28, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, K.B.; Crandall, J.E.; Kosik, K.S.; Williams, R.S. Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 (MAP 2) Immunoreactivity in Human Fetal Neocortex. Brain Res. 1988, 449, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.J.; Shatz, C.J. The Earliest-Generated Neurons of the Cat Cerebral Cortex: Characterization by MAP2 and Neurotransmitter Immunohistochemistry during Fetal Life. J. Neurosci. 1989, 9, 1648–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; Song, K.-S.; Xu, B.; Wang, T. Role of Potassium Channels in Female Reproductive System. Obs. Gynecol. Sci. 2020, 63, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnitz, W.; Lorca, R.A. Potassium Channels in the Uterine Vasculature: Role in Healthy and Complicated Pregnancies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-Q.; Zhang, L. Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels and the Regulation of the Uteroplacental Circulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, K.M.; Lockhart, K.; Stoecklein, K.; Schnabel, R.D.; Spencer, T.E.; Ortega, M.S. Genome-Wide Association Analyses Identify Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Associated with in Vitro Embryo Cleavage and Blastocyst Rates in Holstein Bulls. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 7775–7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Qi, Y.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Y. Cryo-EM Structure of SMG1–SMG8–SMG9 Complex. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwain, D.R.; Pan, Q.; Reilly, P.T.; Elia, A.J.; McCracken, S.; Wakeham, A.C.; Itie-Youten, A.; Blencowe, B.J.; Mak, T.W. Smg1 Is Required for Embryogenesis and Regulates Diverse Genes via Alternative Splicing Coupled to Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12186–12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, C.-H.; Chousal, J.; Goetz, A.; Shum, E.Y.; Brafman, D.; Liao, X.; Mora-Castilla, S.; Ramaiah, M.; Cook-Andersen, H.; Laurent, L.; et al. Nonsense-Mediated RNA Decay Influences Human Embryonic Stem Cell Fate. Stem Cell Rep. 2016, 6, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, R.; Anazi, S.; Ben-Omran, T.; Seidahmed, M.Z.; Caddle, L.B.; Palmer, K.; Ali, R.; Alshidi, T.; Hagos, S.; Goodwin, L.; et al. Mutations in SMG9, Encoding an Essential Component of Nonsense-Mediated Decay Machinery, Cause a Multiple Congenital Anomaly Syndrome in Humans and Mice. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahikkala, E.; Urpa, L.; Ghimire, B.; Topa, H.; Kurki, M.I.; Koskela, M.; Airavaara, M.; Hämäläinen, E.; Pylkäs, K.; Körkkö, J.; et al. A Novel Variant in SMG9 Causes Intellectual Disability, Confirming a Role for Nonsense-Mediated Decay Components in Neurocognitive Development. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, V.B.; Schenkel, F.S.; Chen, S.-Y.; Oliveira, H.R.; Casey, T.M.; Melka, M.G.; Brito, L.F. Genomewide Association Analyses of Lactation Persistency and Milk Production Traits in Holstein Cattle Based on Imputed Whole-Genome Sequence Data. Genes 2021, 12, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyesus, G.; Buitenhuis, A.J.; Poulsen, N.A.; Visker, M.H.P.W.; Zhang, Q.; van Valenberg, H.J.F.; Sun, D.; Bovenhuis, H. Combining Multi-Population Datasets for Joint Genome-Wide Association and Meta-Analyses: The Case of Bovine Milk Fat Composition Traits. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 11124–11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, D.P.; Friggens, N.C.; Lucy, M.; Roche, J.R. Milk Production and Fertility in Cattle. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2016, 4, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinet, A.; Mattalia, S.; Vallée, R.; Bertrand, C.; Barbat, A.; Promp, J.; Cuyabano, B.C.D.; Boichard, D. Effect of Temperature-Humidity Index on the Evolution of Trade-Offs between Fertility and Production in Dairy Cattle. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2024, 56, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloo, R.D.; Mrode, R.; Ekine-Dzivenu, C.C.; Ojango, J.M.K.; Bennewitz, J.; Gebreyohanes, G.; Okeyo, A.M.; Chagunda, M.G.G. Genetic Relationships Among Resilience, Fertility and Milk Production Traits in Crossbred Dairy Cows Performing in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2025, 142, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Castillero, M.; Pegolo, S.; Sartori, C.; Toledo-Alvarado, H.; Varona, L.; Degano, L.; Vicario, D.; Finocchiaro, R.; Bittante, G.; Cecchinato, A. Genetic Correlations between Fertility Traits and Milk Composition and Fatty Acids in Holstein-Friesian, Brown Swiss, and Simmental Cattle Using Recursive Models. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 6832–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.L.; Pryce, J.E.; Xu, Z.Z.; Montgomerie, W.A. Development of New Fertility Breeding Values in the Dairy Industry. Proc. New Zealand Soc. Anim. Prod. 2006, 66, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jayawardana, J.M.D.R.; Lopez-Villalobos, N.; McNaughton, L.R.; Hickson, R.E. Genomic Regions Associated with Milk Composition and Fertility Traits in Spring-Calved Dairy Cows in New Zealand. Genes 2023, 14, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, J.M.; Totir, L.R.; Kachman, S.D.; Fernando, R.L.; Wilson, D.E. Pregnancy Rate and First-Service Conception Rate in Angus Heifers1. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 2022–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, H.; Pakdel, A.; Nejati-Javaremi, A.; Mehrabani-Yeganeh, H.; Honarvar, M.; González-Recio, O.; Carabaño, M.J.; Alenda, R. Genetic Variance Components for Female Fertility in Iranian Holstein Cows. Livest. Sci. 2011, 139, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.O.; Kizilkaya, K.; Garrick, D.J.; Fernando, R.L.; Reecy, J.M.; Weaber, R.L.; Silver, G.A.; Thomas, M.G. Heritability and Bayesian Genome-Wide Association Study of First Service Conception and Pregnancy in Brangus Heifers1. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahbar, R.; Aminafshar, M.; Abdullahpour, R.; Chamani, M. Genetic Analysis of Fertility Traits of Holstein Dairy Cattle in Warm and Temperate Climate. Acta Scientiarum. Anim. Sci. 2016, 38, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxworthy, H.M.; Enns, R.M.; Thomas, M.G.; Speidel, S.E. The Estimation of Heritability and Repeatability of First Service Conception and First Cycle Calving in Angus Cattle. Trans. Anim. Sci. 2019, 3, 1646–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezende, F.M.; Dietsch, G.O.; Peñagaricano, F. Genetic Dissection of Bull Fertility in US Jersey Dairy Cattle. Anim. Genet. 2018, 49, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, S.; Sargolzaei, M.; Abo-Ismail, M.K.; Miller, S.; Schenkel, F.; Moore, S.S.; Stothard, P. Genome-Wide Association Study for Lactation Persistency, Female Fertility, Longevity, and Lifetime Profit Index Traits in Holstein Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 1246–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| BTA 1 | Locus 2 | SNP Count 3 | FDR 4 | PVE (%) 5 | Positional Candidate Genes for Locus 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 4.98 × 10−2 | 0.003 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 3.83 × 10−2 | 0.0037 | SLC19A1, LOC100849587, PCBP3 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 1.96 × 10−3 | 0.0051 | |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 1.52 × 10−3 | 0.005 | |

| 7 | 5 | 3 | 1.96 × 10−3 | 0.004 | LOC100140613 |

| 14 | 6 | 3 | 1.59 × 10−3 | 0.004 | |

| 17 | 7 | 1 | 3.80 × 10−3 | 0.004 | |

| 24 | 8 | 1 | 5.30 × 10−3 | 0.004 | BCL2 |

| 25 | 9 | 1 | 4.21 × 10−2 | 0.003 | |

| 25 | 10 | 9 | 5.80 × 10−4 | 0.005 | TMEM225B, LOC112444278, ZNF655, ZNF789 |

| 25 | 11 | 1 | 2.41 × 10−2 | 0.004 | OCM, LOC100850875, CCZ1, RSPH10B |

| 25 | 12 | 1 | 1.62 × 10−2 | 0.004 | MMD2, RADIL |

| 26 | 13 | 2 | 1.44 × 10−3 | 0.005 | CNNM2, TAF5, ATP5MK, MIR1307, PDCD11, LOC104975977 |

| 27 | 14 | 3 | 1.67 × 10−3 | 0.005 | |

| 27 | 15 | 3 | 1.34 × 10−3 | 0.005 | LOC112444679, LOC107131907, LOC781220 |

| X | 16 | 6 | 1.66 × 10−3 | 0.004 | MORF4L2, LOC101901997, GLRA4 |

| BTA 1 | Locus 2 | SNP Count 3 | FDR 4 | PVE (%) 5 | Positional Candidate Genes for Locus 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3.43 × 10−2 | 0.007 | SCAF4, SOD1, TRNAG-CCC |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 3.36 × 10−2 | 0.007 | GULP1 |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 3.77 × 10−2 | 0.007 | SCRN3, CIR1, LOC112443637 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 1.81 × 10−3 | 0.013 | MAP2 |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | 3.82 × 10−2 | 0.007 | |

| 3 | 6 | 1 | 2.85 × 10−2 | 0.008 | TRNAG-UCC, OR10J30P, APCS |

| 6 | 7 | 1 | 5.54 × 10−3 | 0.01 | |

| 8 | 8 | 2 | 3.03 × 10−2 | 0.007 | GALNTL6 |

| 8 | 9 | 15 | 3.65 × 10−2 | 0.007 | LOC132345943 |

| 8 | 10 | 12 | 7.33 × 10−3 | 0.01 | SYK |

| 8 | 11 | 1 | 2.53 × 10−2 | 0.008 | ECPAS |

| 9 | 12 | 2 | 3.08 × 10−2 | 0.007 | PRKN |

| 10 | 13 | 1 | 3.71 × 10−2 | 0.007 | |

| 11 | 14 | 1 | 3.39 × 10−2 | 0.007 | KANSL3, FER1L5 |

| 12 | 15 | 1 | 3.76 × 10−2 | 0.007 | FARP1, LOC112449164 |

| 14 | 16 | 3 | 4.34 × 10−3 | 0.01 | CPA6 |

| 14 | 17 | 6 | 3.56 × 10−2 | 0.007 | |

| 14 | 18 | 4 | 3.86 × 10−2 | 0.007 | |

| 15 | 19 | 1 | 3.82 × 10−2 | 0.007 | LOC101903557, LOC100848689, MIR125B-1 |

| 15 | 20 | 1 | 3.07 × 10−2 | 0.008 | LOC132342364 |

| 18 | 21 | 1 | 2.17 × 10−2 | 0.008 | |

| 18 | 22 | 2 | 2.07 × 10−3 | 0.012 | |

| 18 | 23 | 1 | 3.26 × 10−2 | 0.007 | ARHGEF1, CD79A, RPS19, DMRTC2, LYPD4 |

| 18 | 24 | 11 | 2.04 × 10−2 | 0.008 | PHLDB3, ETHE1, XRCC1, PINLYP, IRGQ, ZNF575, SRRM5, ZNF428, CADM4, PLAUR |

| 18 | 25 | 11 | 2.87 × 10−3 | 0.011 | LYPD5, ZNF283, IRGC, KCNN4, SMG9, LOC104974883, LOC512005, LOC526915, LOC616722 |

| 18 | 26 | 6 | 9.57 × 10−3 | 0.009 | ZNF226, ZNF227, ZNF233 |

| 18 | 27 | 2 | 1.97 × 10−2 | 0.008 | NOVA2, LOC112442342 |

| 19 | 28 | 1 | 3.18 × 10−2 | 0.007 | RNF157, FOXJ1 |

| 21 | 29 | 1 | 3.08 × 10−2 | 0.007 | STXBP6 |

| 21 | 30 | 1 | 3.06 × 10−2 | 0.008 | TTC6 |

| 22 | 31 | 3 | 3.65 × 10−2 | 0.007 | CRTAP, SUSD5, FBXL2, LOC112443433 |

| 23 | 32 | 1 | 1.77 × 10−2 | 0.008 | LYRM4, PPP1R3G |

| 24 | 33 | 21 | 1.43 × 10−2 | 0.008 | ZNF407 |

| 24 | 34 | 1 | 3.76 × 10−2 | 0.007 | DIPK1C, C24H18orf63, SPACDR |

| 24 | 35 | 1 | 2.89 × 10−2 | 0.008 | |

| 24 | 36 | 1 | 3.09 × 10−2 | 0.008 | |

| 24 | 37 | 1 | 3.05 × 10−2 | 0.008 | |

| 24 | 38 | 1 | 1.42 × 10−2 | 0.008 | RTTN |

| 24 | 39 | 1 | 1.36 × 10−2 | 0.008 | CD226 |

| 24 | 39 | 1 | 1.39 × 10−2 | 0.008 | CD226 |

| 24 | 40 | 4 | 3.31 × 10−2 | 0.007 | SERPINB8, TRNAK-UUU, LOC112444149 |

| 25 | 41 | 1 | 3.20 × 10−2 | 0.007 | NYAP1, TSC22D4, SPACDR, PPP1R35, MEPCE, ZCWPW1 |

| 29 | 42 | 3 | 8.52 × 10−3 | 0.01 | FAT3, LOC112444945 |

| 29 | 43 | 1 | 3.89 × 10−2 | 0.007 | MEN1, TRNAE-CUC, CDC42BPG, EHD1 |

| X | 44 | 2 | 3.42 × 10−2 | 0.007 | LOC101902122, TRNAC-ACA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Issaka Salia, O.; Suarez, E.M.; Murdoch, B.M.; Kelson, V.C.; Herrick, A.L.; Kiser, J.N.; Neibergs, H.L. Identifying the Genetic Basis of Fetal Loss in Cows and Heifers Through a Genome-Wide Association Analysis. Animals 2026, 16, 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020293

Issaka Salia O, Suarez EM, Murdoch BM, Kelson VC, Herrick AL, Kiser JN, Neibergs HL. Identifying the Genetic Basis of Fetal Loss in Cows and Heifers Through a Genome-Wide Association Analysis. Animals. 2026; 16(2):293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020293

Chicago/Turabian StyleIssaka Salia, Ousseini, Emaly M. Suarez, Brenda M. Murdoch, Victoria C. Kelson, Allison L. Herrick, Jennifer N. Kiser, and Holly L. Neibergs. 2026. "Identifying the Genetic Basis of Fetal Loss in Cows and Heifers Through a Genome-Wide Association Analysis" Animals 16, no. 2: 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020293

APA StyleIssaka Salia, O., Suarez, E. M., Murdoch, B. M., Kelson, V. C., Herrick, A. L., Kiser, J. N., & Neibergs, H. L. (2026). Identifying the Genetic Basis of Fetal Loss in Cows and Heifers Through a Genome-Wide Association Analysis. Animals, 16(2), 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020293