Integrated Targeted and Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals the Toxic Mechanisms of Zearalenone in Goat Leydig Cells

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Sampling

2.2. Isolation, Culture and Identification of Testicular LCs

2.3. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Analysis

2.4. Electron Microscopy Observation

2.5. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

2.6. Cells Healing Ability Test

2.7. Assessment of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Using JC-1 Assay

2.8. Flow Cytometric Cycle Assay

2.9. Targeted Metabolomics Analysis

2.10. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cell Purity Identification

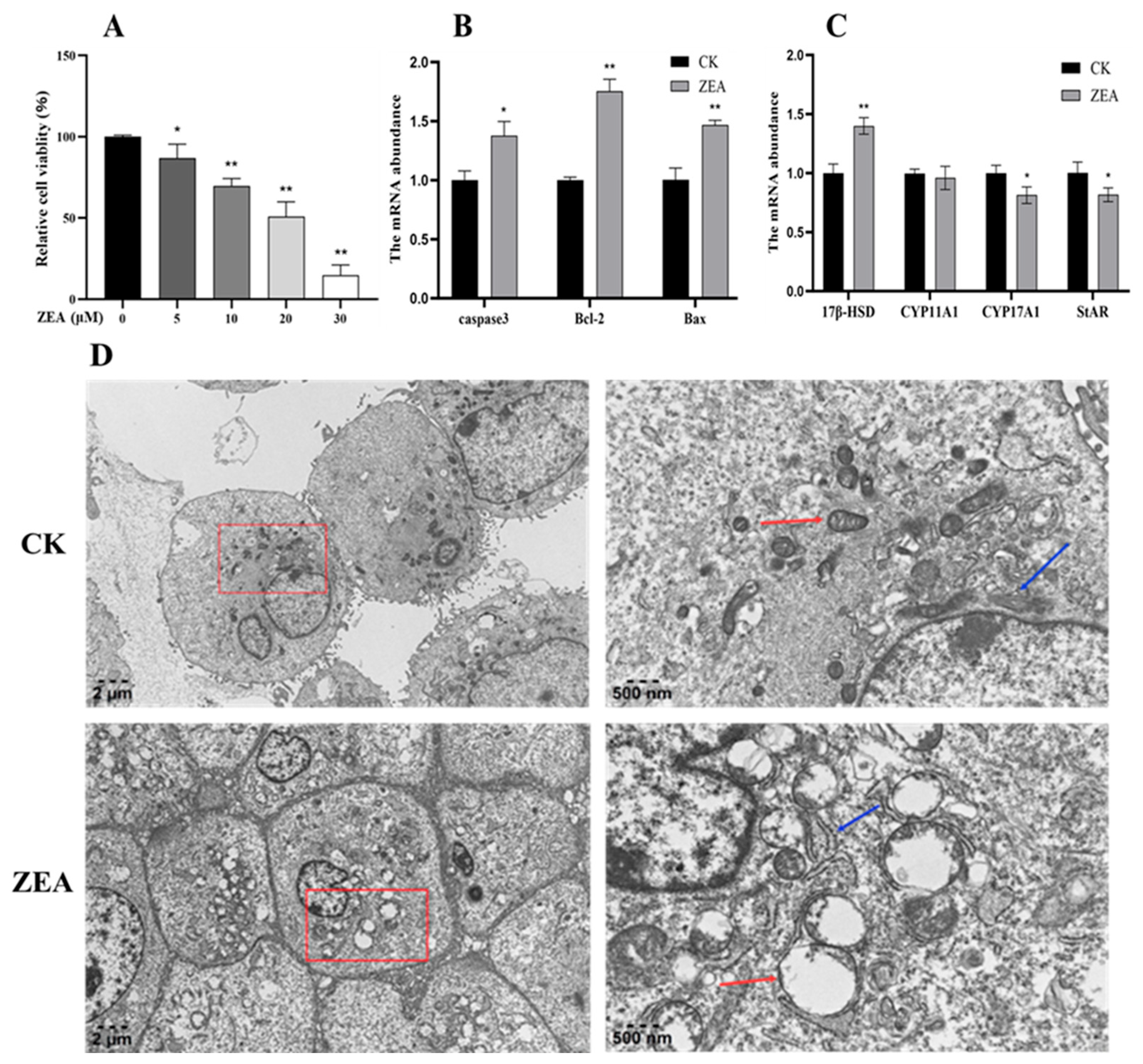

3.2. Effects of ZEA on LCs Viability

3.3. Effects of ZEA on mRNA Expression of Genes Related to LCs

3.4. ZEA Affects the Ultrastructure of the LCs in Goats

3.5. ZEA Impairs the Wound-Healing Ability of LCs

3.6. Effects of ZEA on Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in LCs

3.7. ZEA Affects the Cell Cycle of Goat LCs

3.8. Targeted Metabolomics Study of ZEA Effects on Goat LCs

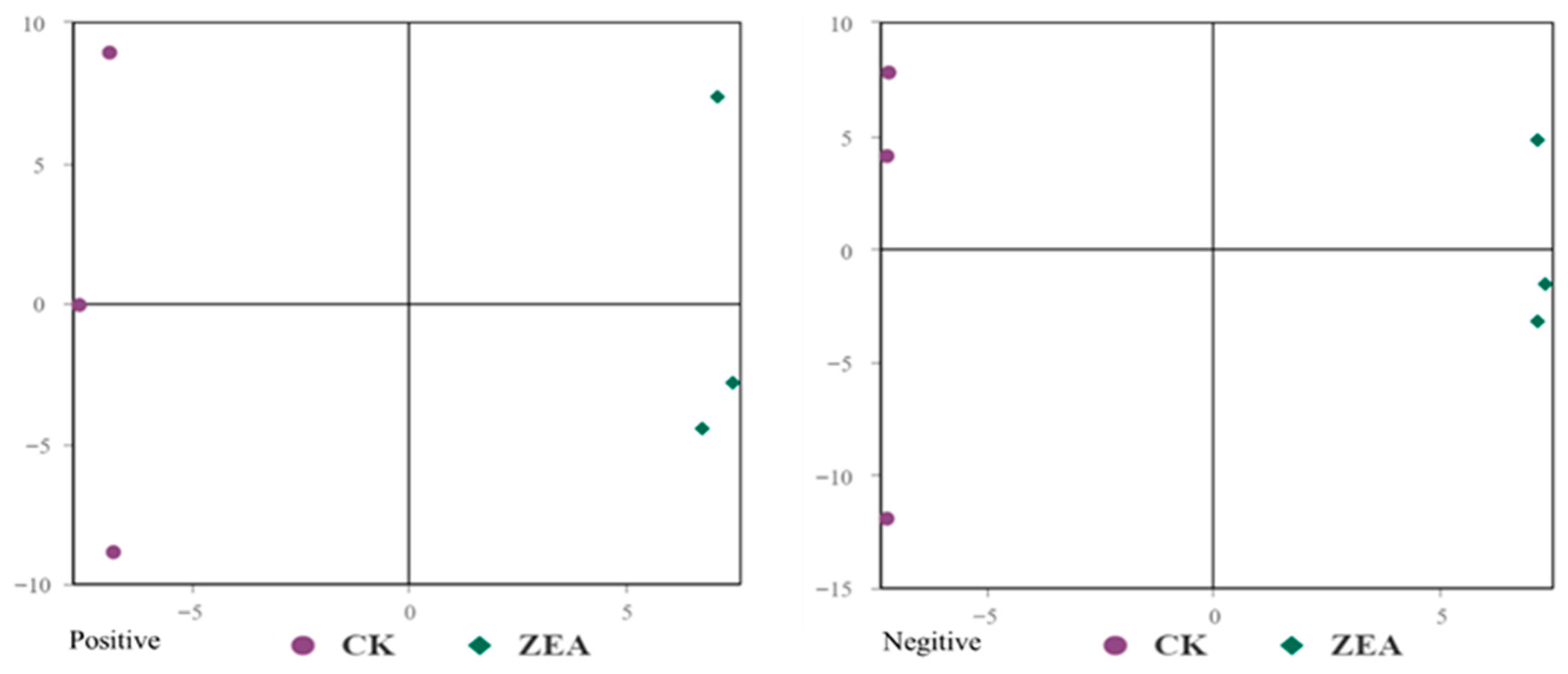

3.9. Untargeted Metabolomic Investigation of ZEA Effects on Goat LCs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gerald, T.; Raj, G. Testosterone and the androgen receptor. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 49, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Garcia, T.M.S.; Low, J.S.; Bauer, C.M. Baseline testosterone levels peak during the inactive period in male degus (Octodon degus). Integr. Org. Biol. 2025, 7, obaf033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diala, E.D.; Arlt, W.; Merke, D.P. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Lancet 2017, 390, 2194–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, M.K.; Nordenström, A.; Lajic, S.; Reisch, N. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Lancet 2023, 401, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balló, A.; Busznyákné, S.K.; Czétány, P.; Márk, L.; Török, A.; Szántó, Á.; Máté, G. Estrogenic and non-estrogenic disruptor effect of zearalenone on Male reproduction: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, X.; Hai, J.; Si, X.; Li, J.; Fu, H.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z. Roles of stress response-related signaling and its contribution to the toxicity of zearalenone in mammals. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3326–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abassi, H.; Ayed-Boussema, I.; Shirley, S.; Abid, S.; Bacha, H.; Micheau, O. The mycotoxin zearalenone enhances cell proliferation, colony formation and promotes cell migration in the human colon carcinoma cell line HCT116. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 254, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.-Q.; Sun, X.-F.; Wu, R.-Y.; Cheng, S.-F.; Zhang, G.-L.; Zhai, Q.-Y.; Liu, X.-L.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, W.; Li, L. Zearalenone exposure elevated the expression of tumorigenesis genes in mouse ovarian granulosa cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 356, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Cao, X.; Ren, H.; Wu, L.; Yan, Y.; Hua, R.; Xing, W.; Lei, M.; Liu, J. Immunotoxicity and uterine transcriptome analysis of the effect of zearalenone (ZEA) in sows during the embryo attachment period. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 357, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, C.; Huang, L.; Niu, Q.; Jiang, S.; Chi, F. Zearalenone Altered the Serum Hormones, Morphologic and Apoptotic Measurements of Genital Organs in Post-weaning Gilts. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Zuo, N.; Tang, J.; Cheng, S.; Li, L.; Tan, J.; Zhang, J.; Shen, W. Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside protects Zearalenone-induced in vitro maturation disorders of porcine oocytes by alleviating NOX4-dependent oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress in cumulus cells. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.; Das, M.; Tripathi, A. Occurrence and toxicity of a fusarium mycotoxin, zearalenone. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2710–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatay, E.; Espín, S.; García-Fernández, A.J.; Ruiz, M.J. Estrogenic activity of zearalenone, α-zearalenol and β-zearalenol assessed using the E-screen assay in MCF-7 cells. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2018, 28, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalsky Paris, M.P.; Schweiger, W.; Hametner, C.; Stückler, R.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Varga, E.; Krska, R.; Berthiller, F.; Adam, G. Zearalenone-16-O-glucoside: A new masked mycotoxin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.Z.; Yang, Z.B.; Yang, W.R.; Gao, J.; Liu, F.X.; Broomhead, J.; Chi, F. Effects of purified zearalenone on growth performance, organ size, serum metabolites, and oxidative stress in postweaning gilts. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 3008–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, L.; Huang, S.; Liu, Q.; Ao, X.; Lei, Y.; Ji, C.; Ma, Q. Zearalenone toxicosis on reproduction as estrogen receptor selective modulator and alleviation of zearalenone biodegradative agent in pregnant sows. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordić, B.; Pribićević, S.; Muntanola-Cvetković, M.; Nikolić, P.; Nikolić, B. Experimental study of the effects of known quantities of zearalenone on swine reproduction. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 1992, 11, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Althali, N.J.; Hassan, A.M.; Abdel-Wahhab, M.A. Effect of grape seed extract on maternal toxicity and in utero development in mice treated with zearalenone. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 5990–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Hai, S.; Chen, J.; Ma, L.; Rahman, S.U.; Zhao, C.; Feng, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Zearalenone Induces Apoptosis in Porcine Endometrial Stromal Cells through JNK Signaling Pathway Based on Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Toxins 2022, 14, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Ji, H.; Xu, Y. ZEA exerts toxic effects on reproduction and development by mediating Dio3os in mouse endometrial stromal cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2019, 33, e22310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ma, J.; Wei, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Wan, Y. Effects of Zearalenone on Apoptosis and Copper Accumulation of Goat Granulosa Cells In Vitro. Biology 2023, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Han, J.; Dong, S.; Chen, X.; He, J. Proanthocyanidin protects against acute zearalenone-induced testicular oxidative damage in male mice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhu, L.; Gao, X.; Kong, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Y.; Wen, L.; Li, R.; Wu, J.; et al. Ameliorative effect of betulinic acid against zearalenone exposure triggers testicular dysfunction and oxidative stress in mice via p38/ERK MAPK inhibition and Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defense activation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 238, 113561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeira, S.P.; Funck, V.R.; Filho, C.B.; Del’fabbro, L.; de Gomes, M.G.; Donato, F.; Royes, L.F.F.; Oliveira, M.S.; Jesse, C.R.; Furian, A.F. Lycopene protects against acute zearalenone-induced oxidative, endocrine, inflammatory and reproductive damages in male mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 230, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Wang, T.; Nepovimova, E.; Long, M.; Li, P.; Kuca, K.; Wu, W. Procyanidins inhibit zearalenone-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress of porcine testis cells through activation of Nrf2 signaling pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 165, 113061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xi, H.; Han, S.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J. Zearalenone induces oxidative stress and autophagy in goat Sertoli cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 252, 114571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Sun, D.; Cui, S. Zearalenone affects reproductive functions of male offspring via transgenerational cytotoxicity on spermatogonia in mouse. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 234, 108766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adibnia, E.; Razi, M.; Malekinejad, H. Zearalenone and 17 β-estradiol induced damages in male rats reproduction potential: Evidence for ERα and ERβ receptors expression and steroidogenesis. Toxicon 2016, 120, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.S.; Rezk, W.R.; El-Naby, A.-S.A.-H.; Mahmoud, K.G.; Takagi, M.; Miyamoto, A.; Megahed, G.A. In vitro effect of zearalenone on sperm parameters, oocyte maturation and embryonic development in buffalo. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 23, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pan, L.; Zou, Z.; Wang, D.; Lu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Zhu, L. Hypoxia reduces testosterone synthesis in mouse Leydig cells by inhibiting NRF1-activated StAR expression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 16401–16413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.R.; Estermann, M.A.; Gruzdev, A.; Scott, G.J.; Hagler, T.B.; Ray, M.K.; Yao, H.H.-C. Generation of a Nr2f2-driven inducible Cre mouse to target interstitial cells in the reproductive system. Biol. Reprod. 2025, 113, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Jiang, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W. Zearalenone exposure affects the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway and glucose nutrient absorption related genes of porcine jejunal epithelial cells. Toxins 2022, 14, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zheng, H.; Fu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Zou, H.; Yuan, Y.; Gu, J.; Liu, Z.; Bian, J. Role of PI3K/Akt-mediated Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in resveratrol aleviation of zearalenone induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in TM4 cells. Toxins 2022, 14, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Bi, J.; Shi, C.; Wang, D.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Diabetes induced autophagy dysregulation engenders testicular impairment via oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2023, 3, 4365895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.O.; Aydin, Y. New insights into the mechanisms underlying 5-hydroxymethylfurfural-induced suppression of testosterone biosynthesis in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2024, 493, 117142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, F.; Caloni, F.; Schreiber, N.; Cortinovis, C.; Spicer, L. In vitro effects of deoxynivalenol and zearalenone major metabolites alone and combined, on cell proliferation, steroid production and gene expression in bovine small follicle granulosa cells. Toxicon 2016, 109, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, N.; Peng, Y.; Qi, D. Interaction of zearalenone and soybean isoflavone on the development of reproductive organs, reproductive hormones and estrogen receptor expression in prepubertal gilts. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 122, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, W.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Bian, J. Zearalenone inhibits testosterone biosynthesis in mouse Leydig cells via the crosstalk of estrogen receptor signaling and orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 expression. Toxicol. In Vitro 2014, 28, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Han, L.; Miao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Pan, L. Estrogen receptor knockdown suggests its role in gonadal development regulation in Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 243, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Jiang, X.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Jiao, R.; Peng, Z.; Li, Y.; Bai, W. Toxic effects of zearalenone on gametogenesis and embryonic development: A molecular point of review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 119, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Huangfu, B.; Xu, T.; Huang, K.; He, X. Zearalenone exacerbates lipid metabolism disorders by promoting liver lipid droplet formation and disrupting gut microbiota. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmihi, K.A.; Leonard, K.A.; Nelson, R.; Thiesen, A.; Clugston, R.D.; Jacobs, R.L. The emerging role of ethanolamine phosphate phospholyase in regulating hepatic phosphatidylethanolamine and plasma lipoprotein metabolism in mice. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdaway, C.M.; Leonard, K.-A.; Nelson, R.; van der Veen, J.; Das, C.; Watts, R.; Clugston, R.D.; Lehner, R.; Jacobs, R.L. Alterations in phosphatidylethanolamine metabolism impacts hepatocellular lipid storage, energy homeostasis, and proliferation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2025, 1870, 159608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, B.; Si, M.; Zou, H.; Song, R.; Gu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, G.; Bai, J.; et al. Zearalenone altered the cytoskeletal structure via ER stress-autophagy-oxidative stress pathway in mouse TM4 Sertoli cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, C.; Hai, S.; Wang, C.; Rahman, S.U.; Huang, W.; Zhao, C.; Feng, S.; Wang, X. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission alleviates zearalenone-induced mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane dysfunction in piglet sertoli cells. Toxins 2023, 15, 253. [Google Scholar]

- Holeček, M. Branched chain amino acids in health and disease: Metabolism, alterations in blood plasma, and as supplements. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.; Yang, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; He, J. The influence of selenium yeast on hematological, biochemical and reproductive hormone level changes in kunming mice following acute exposure to zearalenone. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016, 174, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Feng, N.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, H.; Zou, H.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Gu, J.; Bian, J. Treatment with, resveratrol, a SIRT1 activator, prevents zearalenone-induced lactic acid metabolism disorder in rat sertoli cells. Molecules 2019, 24, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Peng, S. Prepubertal exposure to an oestrogenic mycotoxin zearalenone induces central precocious puberty in immature female rats through the mechanism of premature activation of hypothalamic kisspeptin-GPR54 signaling. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2016, 437, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Gao, L.; Li, F.; Cui, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, B. Effects of zearalenone on ovarian development of prepubertal gilts through growth hormone axis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 950063. [Google Scholar]

- Gajęcka, M.; Zielonka, Ł.; Babuchowski, A.; Gajęcki, M.T. Exposure to low zearalenone doses and changes in the homeostasis and concentrations of endogenous hormones in selected steroid-sensitive tissues in pre-pubertal gilts. Toxins 2022, 14, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Prime Sequence | Size (bp) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bcl-2 | F: ATGTGTGTGGAGAGCGTCA R: AGAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATC | 182 | 60 |

| Bax | F: CATCGGAGATGAATTGGACAGTAA R: GGCCTTGAGCACCAGTTTGC | 178 | 60 |

| Caspase 3 | F: CATTATTCAGGCCTGCCGAG R: CTCGAGCTTGTGAGCGTACT | 220 | 58 |

| StAR | F: GCGACCAAGAGCTTGCCTATATCC R: CTCTCCTTCTTCCAGCCCTCCTG | 94 | 57 |

| CYP17A1 | F: GGCCCAAGACCAAGCACTC R: GGAACCCAAACGAAAGGAATAG | 161 | 60 |

| CYP11A1 | F: ATGGCTCCAGAGGCAATAAA R: AAGGCAAAGTGAAACAGGTC | 146 | 56 |

| 17β-HSD | F: GGCGGTCCTCGTGGTCCTATAC R: TGGTTCCCGAAGCCTGAGTCAC | 117 | 58 |

| β-actin | F: CTGAGCGCAAGTACTCCGTGT R: GCATTTGCGGTGGACGAT | 125 | 60 |

| Name | Standard Curve Equation | CK | ZEA | SEM | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone (pg/mL) | y = 0.9x − 0.000396 | 2.53 b | 5.10 a | 0.0007 | <0.05 |

| Corticosterone (pg/mL) | y = 0.452x − 0.00676 | 19.07 b | 24.10 a | 0.0018 | <0.05 |

| 5-α-Dihydrotestosterone (pg/mL) | y = 0.246x − 0.00172 | 16.40 a | 13.27 b | 0.0005 | <0.05 |

| Pregnenolone (pg/mL) | y = 0.105x − 0.000895 | 10.87 | 11.37 | 0.0029 | >0.05 |

| Progesterone (pg/mL) | y = 0.384x − 0.000954 | 4.00 b | 5.50 a | 0.0003 | <0.05 |

| 11-Deoxycortisol (pg/mL) | y = 0.77x − 0.000355 | 1.57 | 2.27 | 0.0003 | >0.05 |

| 11-Deoxycorticosterone (pg/mL) | y = 0.995x + 0.00039 | 0.06 b | 0.57 a | 0.0001 | <0.05 |

| Androstenedione (pg/mL) | y = 1.06x + 0.0006 | 16.70 b | 27.20 a | 0.0014 | <0.05 |

| Cortisone (pg/mL) | y = 0.649x − 0.000319 | 2.81 b | 4.40 a | 0.0001 | <0.05 |

| Testosterone (pg/mL) | y = 0.584x + 0.000157 | 2.11 | 2.00 | 0.0002 | >0.05 |

| Cortisol (pg/mL) | y = 0.465x + 0.000628 | 7.83 | 20.10 | 0.0091 | >0.05 |

| Dehydroepisndrosterone (pg/mL) | y = 0.243x + 0.00264 | 34.85 | 40.37 | 0.0065 | >0.05 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | y = 0.852x − 0.00285 | 5.05 | 3.73 | 0.0006 | >0.05 |

| Aldosterone (pg/mL) | y = 0.271x + 0.00109 | 0.0002 | 0.0036 | 0.0013 | >0.05 |

| Estriol (pg/mL) | y = 0.628x + 0.000594 | 2.46 | 2.73 | 0.0021 | >0.05 |

| Estrone (pg/mL) | y = 0.663x + 5.21 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.00004 | >0.05 |

| 17A-Hydroxypregnenolone (pg/mL) | y = 0.256x + 0.00146 | 3.43 | 1.57 | 0.0001 | >0.05 |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate (ng/mL) | y = 0.011x − 0.0116 | 1.16 | 1.17 | 0.0065 | >0.05 |

| Number | Name | Fold Change | p | VIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (+)-6-aminopenicillanic acid | 0.84 | 0.04 | 4.42 |

| 2 | (r)-butyrylcarnitine | 0.29 | 0.00 | 3.25 |

| 3 | 1-(1z-hexadecenyl)-sn-glycero-3- 2-phosphocholine | 0.41 | 0.03 | 1.24 |

| 4 | 1-(1z-octadecenyl)-2-(9z-octadecenoyl)- 2-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (18:0/18:1) | 1.26 | 0.01 | 4.16 |

| 5 | 1-hexadecanoyl-2-octadecadienoyl-sn- 2-glycero-3-phosphocholine (16:0/16:2) | 1.22 | 0.00 | 5.31 |

| 6 | 1-hexadecyl-2-(8z,11z,14z-eicosatrienoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (16:0/20:3) | 1.24 | 0.00 | 2.93 |

| 7 | 1-hexadecyl-2-(9z-octadecenoyl)-sn- 2-glycero-3-phosphocholine (16:0/18:1) | 1.18 | 0.01 | 7.22 |

| 8 | 1-hexadecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (O-16:0/0:0) | 0.36 | 0.05 | 3.22 |

| 9 | 1-oleoyl-2-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3- 2-phosphocholine (18:1/16:0) | 0.92 | 0.04 | 4.71 |

| 10 | 1-palmitoyl-2-lauroyl-sn-glycero-3- phosphorylcholine | 1.34 | 0.00 | 1.99 |

| 11 | 1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3- Phosphocholine (16:0/16:0) | 0.80 | 0.00 | 5.33 |

| 12 | 1,2-dipalmitoleoyl-sn-glycero-3- Phosphocholine (16:1/16:1) | 1.41 | 0.00 | 2.57 |

| 13 | 18-β-glycyrrhetic acid methyl ester | 0.17 | 0.00 | 2.25 |

| 14 | 4-hydroxy-1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2,2,6,6- tetramethylpiperidine | 0.21 | 0.00 | 13.03 |

| 15 | 7-α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one | 2.74 | 0.00 | 2.60 |

| 16 | Acetylcholine | 0.54 | 0.00 | 1.43 |

| 17 | Citrulline | 2.00 | 0.05 | 1.04 |

| 18 | Diethanolamine | 0.42 | 0.01 | 1.75 |

| 19 | Dimethyl phthalate | 0.60 | 0.02 | 1.21 |

| 20 | Glutamic acid | 1.16 | 0.00 | 1.16 |

| Number | Name | Fold Change | p | VIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (16:0/18:2) | 1.85 | 0.00 | 1.51 |

| 2 | 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (18:0/18:2) | 1.27 | 0.01 | 1.57 |

| 3 | 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol | 1.23 | 0.04 | 2.43 |

| 4 | 6-Hydroxydopamine | 1.45 | 0.00 | 1.07 |

| 5 | Cis-7,10,13,16-docosatetraenoic acid | 0.63 | 0.02 | 1.91 |

| 6 | Cis-9-palmitoleic acid | 1.48 | 0.01 | 2.85 |

| 7 | D-aspartic acid | 2.25 | 0.00 | 1.06 |

| 8 | Lactate acid | 0.44 | 0.00 | 1.97 |

| 9 | Glutamic acid | 1.30 | 0.01 | 1.44 |

| 10 | Linoleic acid | 1.15 | 0.01 | 1.32 |

| 11 | N-benzyloxycarbonylglycine | 1.32 | 0.03 | 2.79 |

| 12 | Pantothenate | 1.78 | 0.00 | 3.97 |

| 13 | PC (18:1/9) | 1.14 | 0.03 | 1.37 |

| 14 | PG (36:2) | 2.03 | 0.00 | 4.82 |

| 15 | PG (36:3) | 1.62 | 0.01 | 1.98 |

| 16 | Taurine | 1.91 | 0.01 | 1.48 |

| 17 | Zearalenone | 55.25 | 0.00 | 4.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ning, C.; Sun, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.; Wu, W.; Yang, Y. Integrated Targeted and Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals the Toxic Mechanisms of Zearalenone in Goat Leydig Cells. Animals 2026, 16, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020283

Ning C, Sun J, Zhao Y, Xu H, Wu W, Yang Y. Integrated Targeted and Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals the Toxic Mechanisms of Zearalenone in Goat Leydig Cells. Animals. 2026; 16(2):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020283

Chicago/Turabian StyleNing, Chunmei, Jinkui Sun, Ying Zhao, Houqiang Xu, Wenxuan Wu, and Yi Yang. 2026. "Integrated Targeted and Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals the Toxic Mechanisms of Zearalenone in Goat Leydig Cells" Animals 16, no. 2: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020283

APA StyleNing, C., Sun, J., Zhao, Y., Xu, H., Wu, W., & Yang, Y. (2026). Integrated Targeted and Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals the Toxic Mechanisms of Zearalenone in Goat Leydig Cells. Animals, 16(2), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020283