First-Stage Algorithm for Photo-Identification and Location of Marine Species

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The content of the image contains elements unrelated to the marine species to be studied, the number of animals in the captured image, or the image has no sufficient representative elements for its use;

- The image acquired can be affected by lighting, blurring, distortion, exposure level, focal length, and others.

- A novel algorithm for the first stage of marine species photo-identification and location methods is presented.

- The proposed method can resolve the limitations (large training data) presented in the deep learning approaches.

- The NGMR (Normalized Green Minus Red) and NBMG (Normalized Blue Minus Green) color indexes are proposed to provide better information about the color of regions (marine animal, sky, and land) found in the scientific sightings

- The proposed method is simple, efficient, and feasible for use under real conditions and in real time in marine species applications. It does not require a lot of computing resources, and its implementation is straightforward on any device and could provide a real-time solution to process marine animal video frames.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proposed Method

2.1.1. Step 1: The Image Dataset

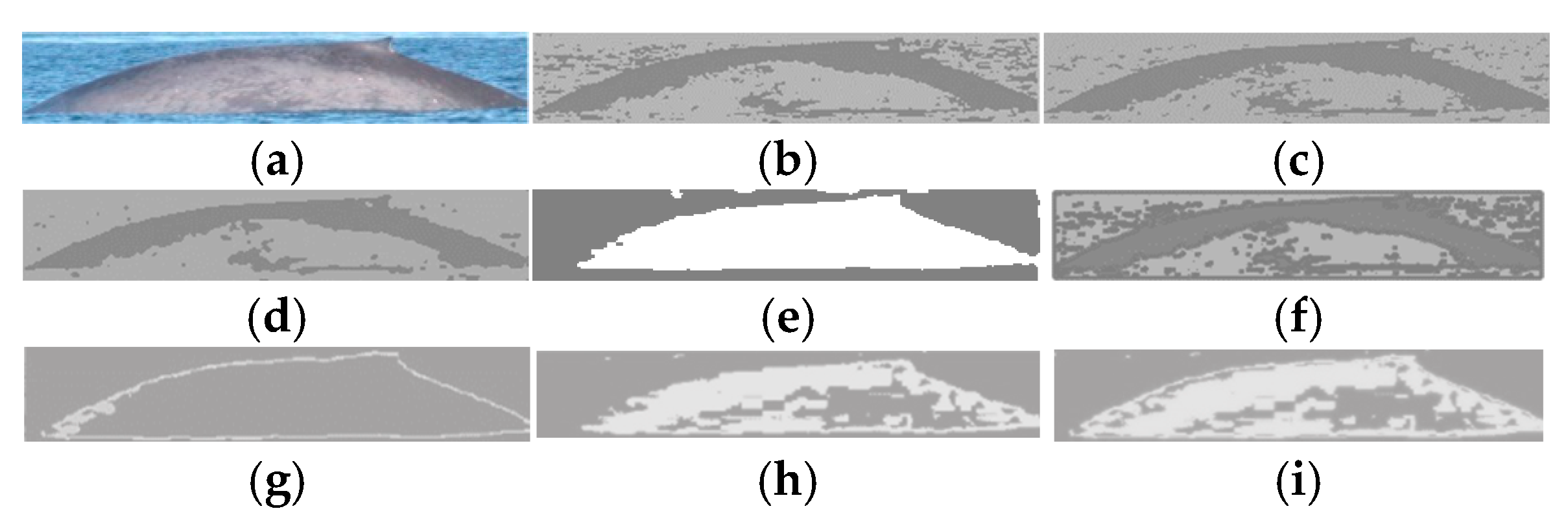

2.1.2. Step 2: Calculation of the Color Indexes

2.1.3. Step 3: Segmentation by Thresholding

- The NGMRCj and NBMGCj images for all ImgCj images of the three classes are computed;

- Morphological operations of dilation and then erosion to all NGMRCj and NBMGCj images from Step 1 are realized to provide more uniform regions in intensity that correspond to the regions that make up a sighting image, obtaining the NGMRmorphCj and NBMGmorphCj images [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Simulations of morphological operations are carried out with different neighborhood sizes of 9 × 9, 10 × 10, 11 × 11, 12 × 12, 13 × 13, and 14 × 14 to find the optimal neighborhood size where the shape and the intensity of pigmentation in the skin of the marine animal are better preserved, and the uniformity of the different objects that make up the land and the sky. This is achieved using a neighborhood size of 11 × 11 pixels;

- The histograms for all NGMRmorphCj and NBMGmorphCj images of each class are obtained, and a threshold for a determined class (land, marine animal, or sky region) of each histogram is found. The optimal thresholds are determined with the average of the thresholds obtained for each class (region). The segmentation thresholds for sky, land, and marine animals were calculated based on the variability of illumination presented in the sightings and the quality of the collected images, where automatic thresholding methods tend to be unstable. This proposal reduces the impact of noise and has a low computational cost. There exist other alternatives, such as automatic thresholding, unsupervised clustering, or deep learning-based segmentation, but these require unmet assumptions, big computational complexity, or unavailable volumes of labeled data. Therefore, the proposed approach is suitable for the objective of this work, which is to optimize resources in the detection of marine animals in heterogeneous images.

2.1.4. Step 4: Selection and Classification of Regions

3. Results

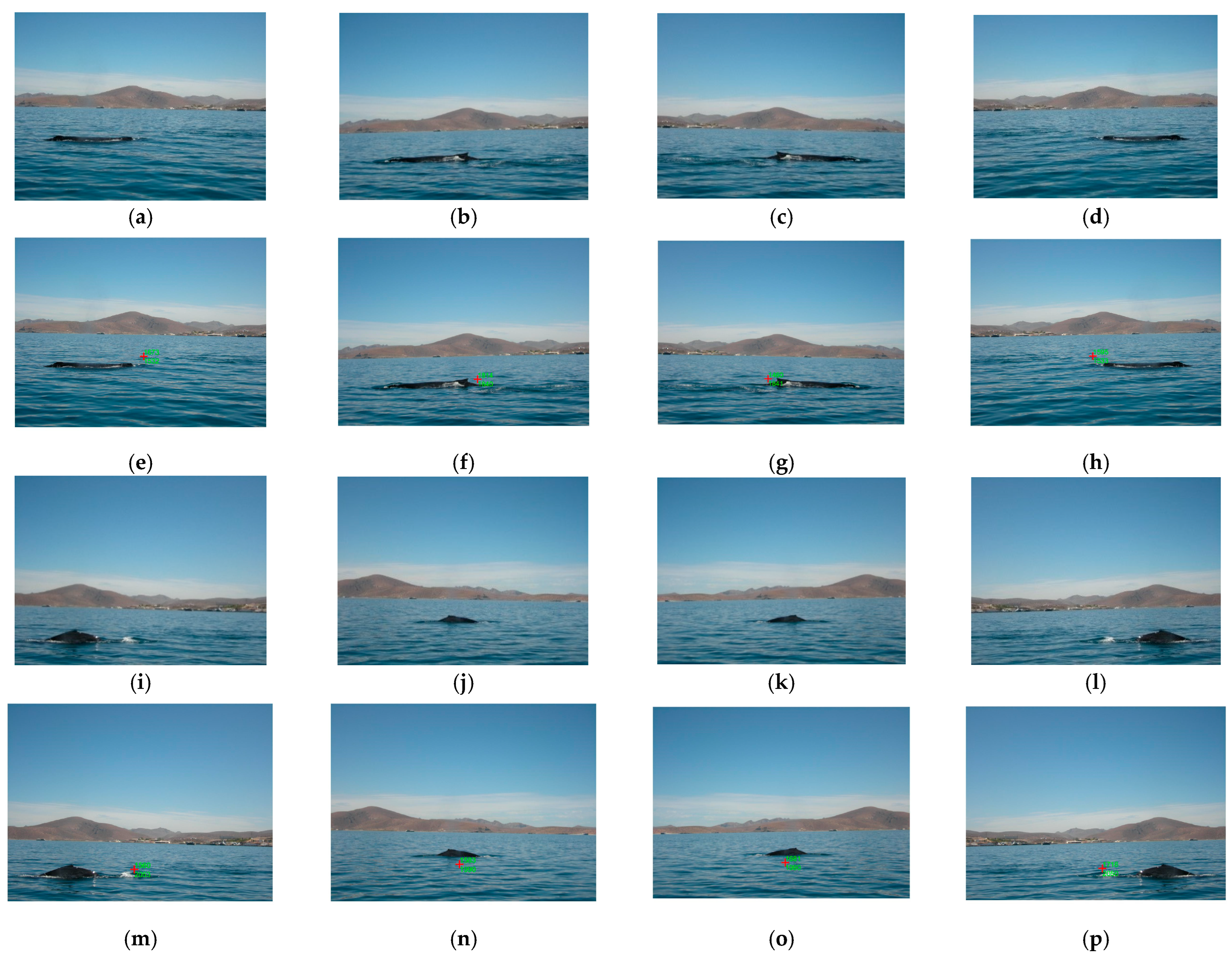

- The coordinates of the marine animal location in the real world can be obtained by transforming the marine animal location coordinates found in each frame, utilizing a computer vision system, and then using these real-world coordinates to move a smart camera to track the specific animal target. In our case, this process is not possible to realize because the dataset used only contains images, and we do not have access to smart cameras with a coordinate mechanism to provide the tracking.

- The proposed algorithm does not use the voxel processing concept or temporal information between video frames by using the information of frame (t − 1) and/or frame (t + 1) to process the actual frame (t); that is, previous or successive frames are not taken into account. The use of various frames improves the performance results because during the tracking process, the algorithm utilizes more information about the movement of the marine animal, which, when utilizing only one frame, is limited by the fact that the processing time is increased. Therefore, the proposed location algorithm for tracking by using one video frame could be limited to solving problems of rapid changes in environmental conditions and/or illumination and other types of problems related to the location of marine animals, such as occlusion, deformation, and rapid movements. These rapid changes could not provide a good segmentation; if the segmentation is not correct, the location of the marine animal is not provided, and the tracking fails. We are sure of the limitations of the proposed algorithm described above, but one of the contributions of the proposed algorithm is the real-time processing of a video frame in any device; the precision and/or accuracy could be decreased.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bogucki, R.; Cygan, M.; Khan, C.B.; Klimek, M.; Milczek, J.K.; Mucha, M. Applying deep learning to right whale photo identification. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendron, D.; Ugalde de la Cruz, A. A new classification method to simplify blue whale photo-identification technique. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 2012, 12, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wursig, B.; Jefferson, T.A. Methods of photo-identification for small cetaceans. Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 1990, 12, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, E.; Iñíguez, M. The State of Whale Watching in Latin America; WDCS: Chippenham, UK.; IFAW: Yarmouth Port, MA, USA; Global Ocean: London, UK, 2008; 60p. [Google Scholar]

- Araabi, B.N.; Kehtarnavaz, N.; McKinney, T.; Hillman, G.; Würsig, B. A String Matching Computer-Assisted System for Dolphin Photoidentification. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2000, 28, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beirão, L.; Cantor, M.; Flach, L.; Galdino, C.A. Short Note Performance of Computer-Assisted Photographic Matching of Guiana Dolphins (Sotalia guianensis). Aquat. Mamm. 2014, 40, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renò, V.; Losapio, G.; Forenza, F.; Politi, T.; Stella, E.; Fanizza, C.; Hartman, K.; Carlucci, R.; Dimauro, G.; Maglietta, R. Combined Color Semantics and Deep Learning for the Automatic Detection of Dolphin Dorsal Fins. Electronics 2020, 9, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranguelova, E.; Huiskes, M.; Pauwels, E.J. Towards computer-assisted photo-identification of humpback whales. In Proceedings of the 2004 International Conference on Image Processing 2004, ICIP ‘04, Singapore, 24–27 October 2004; Volume 3, pp. 1727–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gope, C.; Kehtarnavaz, N.; Hillman, G.; Würsig, B. An affine invariant curve matching method for photo-identification of marine mammals. Pattern Recognit. 2005, 38, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawley, M.D.M.; Hupman, K.E.; Stockin, K.A.; Gilman, A. Examining the viability of dorsal fin pigmentation for individual identification of poorly-marked delphinids. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.; Wu, P.-Y.; Chou, L.-S.; Yang, W.-C. Skin Marks in Critically Endangered Taiwanese Humpback Dolphins (Sousa chinensis taiwanensis). Animals 2023, 13, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urian, K.; Gorgone, A.; Read, A.; Balmer, B.; Wells, R.S.; Berggren, P.; Durban, J.; Eguchi, T.; Reyment, W.; Hammond, P.S. Recommendations for photo-identification methods used in capture-recapture models with cetaceans. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2015, 31, 298–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadeiro, V.; Rodriguez, A.; Henry, J.; Wlodkowic, D.; Andersson, M. A review of 28 free animal-tracking software applications: Current features and limitations. Lab Anim. 2021, 50, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Feng, J.; Dong, S. Learning Rich Feature Representation and State Change Monitoring for Accurate Animal Target Tracking. Animals 2024, 14, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Bist, R.B.; Paneru, B.; Chai, L. Deep Learning Methods for Tracking the Locomotion of Individual Chickens. Animals 2024, 14, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanikommu, V.; Sura, A.; Chimirala, P. Deep learning-based detection and tracking of fin whales using high-resolution space-borne remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 38, 101580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollicelli, D.; Coscarella, M.; Delrieux, C. RoI detection and segmentation algorithms for marine mammals photo-identification. Ecol. Inform. 2020, 56, 101038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman Oion, M.S.; Islam, M.; Amir, F.; Ali, M.E.; Habib, M.; Hossain, M.S. Marine animal classification using deep learning and convolutional neural networks (CNN). In Proceedings of the 2023 26th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT) IEEE, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 13–15 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Xuan, C.; Ma, Y.; Tang, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhang, H. High-similarity sheep face recognition method based on a Siamese network with fewer training samples. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhou, P.; Wang, C.-S.; Fu, G.-Y.; Xu, X.-W.; Niu, Z. FishAI: Automated hierarchical marine fish image classification with vision transformer. Eng. Rep. 2024, 6, e12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, B.-Y.; Paeng, D.-G. Bottlenose dolphin identification using synthetic image-based transfer learning. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 84, 102909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Xiao, X. Multiobject Tracking of Wildlife in Videos Using Few-Shot Learning. Animals 2022, 12, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkozhayeva, D.; Cisar, P. Image-Based Automatic Individual Identification of Fish without Obvious Patterns on the Body (Scale Pattern). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, T.; Southerland, K.; Park, J.; Olio, M.; Flynn, K.; Calambokidis, J.; Clapham, P. Advanced image recognition: A fully automated, high-accuracy photo-identification matching system for humpback whales. Mamm. Biol. 2022, 102, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J. Estimating nitrogen status of rice using the image segmentation of G-R thresholding method. Field Crops Res. 2013, 149, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Martínez, M.A.; Gallegos-Funes, F.J.; Carvajal-Gámez, B.E.; Urriolagoitia-Sosa, G.; Rosales-Silva, A.J. Color index based thresholding method for background and foreground segmentation of plant images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 178, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, S.; Haralick, R.M. Feature normalization and likelihood-based similarity measures for image retrieval. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2001, 22, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Boomgaard, R.; Van Balen, R. Methods for fast morphological image transforms using bitmapped binary images. CVGIP Graph. Models Image Process. 1992, 54, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R. Radial decomposition of disks and spheres. CVGIP Graph. Models Image Process. 1993, 55, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Kim, C.-S.; Jay, K.C.-C. Interactive Segmentation Techniques: Algorithms and Performance Evaluation, 1st ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Maloigne, C. Advanced Color Image Processing and Analysis, 1st ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Soltani, S.; Wong, A.K.C. A survey of thresholding techniques. Comput. Vis. Graph. Image Process. 1988, 41, 233–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, P. Machine Learning: The Art and Science of Algorithms That Make Sense of Data, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shapiro, L.G. Computer and Robot Vision, 1st ed.; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, G. Pattern Recognition and Classification: An Introduction, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labatut, V.; Cherifi, H. Accuracy measures for the comparison of classifiers. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information Technology, Amman, Jordan, 11–13 May 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E.; Eddins, S.L. Digital Image Processing Using. MATLAB, 3rd ed.; MathWorks Gatesmark Publishing: Natick, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, H.; Ess, A.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. Speeded Up Robust Features (SURF). Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2008, 110, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, P.P.R.; Moreira, F.D.L.; Xavier, F.G.D.L.; Gomes, S.L.; Santos, J.C.D.; Freitas, F.N.C.; Freitas, R.G. New Analysis Method Application in Metallographic Images through the Construction of Mosaics via Speeded up Robust Features and Scale Invariant Feature Transform. Materials 2015, 8, 3864–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.K.; Choi, I.H.; Lim, M.T. MDGHM-SURF: A robust local image descriptor based on modified discrete Gaussian–Hermite moment. Pattern Recognit. 2015, 48, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykora, P.; Kamencay, P.; Hudec, R. Comparison of SIFT and SURF Methods for Use on Hand Gesture Recognition based on Depth Map. AASRI Procedia 2014, 9, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.deeplearningbook.org (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Borchers, D.L.; Buckland, S.T.; Zucchini, W. Estimating Animal Abundance: Closed Populations; Springer: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, P.T.; Cheeseman, T.; Abe, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Reade, W.; Southerland, K.; Howard, A.; Oleson, E.M.; Allen, J.B.; Ashe, E.; et al. A deep learning approach to photo–identification demonstrates high performance on two dozen cetacean species. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 2611–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, C.; Blount, D.; Parham, J.; Holmberg, J.; Hamilton, P.; Charlton, C.; Christiansen, F.; Johnston, D.; Rayment, W.; Dawson, S.; et al. Artificial intelligence for right whale photo identification: From data science competition to worldwide collaboration. Mamm. Biol. 2022, 102, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, V.; Dussert, G.; Spataro, B.; Chamaillé-Jammes, S.; Allainé, D.; Bonenfant, C. Revisiting animal photo-identification using deep metric learning and network analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraggi, D.; Reiser, B. Estimation of the area under the ROC curve. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 3093–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Gamez, B.E.; Trejo-Salazar, D.B.; Gendron, D.; Gallegos Funes, F.J. Photo-id of Blue Whale by means of the Dorsal Fin using Clustering algorithms and Color Local Complexity Estimation for Mobile Devices. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2017, 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamino-Sánchez, F.; Hernández-Gutiérrez, I.V.; Rosales-Silva, A.J.; Gallegos-Funes, F.J.; Mújica-Vargas, D.; Ramos-Diaz, E.; Carvajal-Gámez, B.E.; Kinani, J.M.V. Block-Matching Fuzzy C-Means (BMFCM) clustering algorithm for segmentation of color images degraded with Gaussian noise. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 73, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siang, K.; Ashidi Mat Isa, N. Color image segmentation using histogram thresholding–Fuzzy C-means hybrid approach. Pattern Recognit. 2011, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Au, O.; Zou, R.; Yu, W.; Tian, J. An adaptive unsupervised approach toward pixel clustering and color image segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2010, 43, 1889–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Song, Y.; Chen, J.; Xie, C.; Zhu, F. Color image segmentation using nonparametric mixture models with multivariate orthogonal polynomials. Neural Comput. Appl. 2012, 22, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Adhami, R.; Bhuiyan, S.; Sobieranski, A. A customized Gabor filter for unsupervised color image segmentation. Image Vis. Comput. 2009, 27, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Sang, N.; Lou, D.; Tang, Q. Image segmentation via coherent clustering in L*a*b color space. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2011, 32, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Images | NGMR | NBMG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNGMRC1 | TNGMRC2a | TNGMRC2b | TNGMRC3 | TNBMGC1 | TNBMGC2a | TNBMGC2b | TNBMGC3 | |

| 5 | 0.3905 | 0.3906 | 0.6211 | 0.6212 | 0.4022 | 0.4023 | 0.6172 | 0.6173 |

| 10 | 0.4335 | 0.4336 | 0.5977 | 0.5978 | 0.4101 | 0.4102 | 0.6211 | 0.6212 |

| 20 | 0.4413 | 0.4414 | 0.5977 | 0.5978 | 0.4101 | 0.4102 | 0.6133 | 0.6134 |

| 40 | 0.4374 | 0.4375 | 0.5820 | 0.5821 | 0.4687 | 0.4688 | 0.6016 | 0.6017 |

| 60 | 0.4491 | 0.4492 | 0.6016 | 0.6017 | 0.4452 | 0.4453 | 0.5898 | 0.5899 |

| 80 | 0.4257 | 0.4258 | 0.5781 | 0.5782 | 0.4608 | 0.4609 | 0.5820 | 0.5821 |

| 100 | 0.4608 | 0.4609 | 0.5781 | 0.5782 | 0.4491 | 0.4492 | 0.5898 | 0.5899 |

| NGMR | NBMG | NGMR + NBMG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classifier Result | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| Positive | 527 | 48 | 461 | 136 | 563 | 13 |

| Negative | 93 | 332 | 104 | 299 | 119 | 305 |

| Total | 620 | 380 | 565 | 435 | 682 | 318 |

| Metric | NGMR | NBMG | NGMR + NBMG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.98 |

| Specificity | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.96 |

| Accuracy | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.87 |

| F-measure | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.90 |

| Recall | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ramos-Arredondo, R.I.; Gallegos-Funes, F.J.; Carvajal-Gámez, B.E.; Urriolagoitia-Sosa, G.; Romero-Ángeles, B.; Rosales-Silva, A.J.; Velázquez-Lozada, E. First-Stage Algorithm for Photo-Identification and Location of Marine Species. Animals 2026, 16, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020281

Ramos-Arredondo RI, Gallegos-Funes FJ, Carvajal-Gámez BE, Urriolagoitia-Sosa G, Romero-Ángeles B, Rosales-Silva AJ, Velázquez-Lozada E. First-Stage Algorithm for Photo-Identification and Location of Marine Species. Animals. 2026; 16(2):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020281

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos-Arredondo, Rosa Isela, Francisco Javier Gallegos-Funes, Blanca Esther Carvajal-Gámez, Guillermo Urriolagoitia-Sosa, Beatriz Romero-Ángeles, Alberto Jorge Rosales-Silva, and Erick Velázquez-Lozada. 2026. "First-Stage Algorithm for Photo-Identification and Location of Marine Species" Animals 16, no. 2: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020281

APA StyleRamos-Arredondo, R. I., Gallegos-Funes, F. J., Carvajal-Gámez, B. E., Urriolagoitia-Sosa, G., Romero-Ángeles, B., Rosales-Silva, A. J., & Velázquez-Lozada, E. (2026). First-Stage Algorithm for Photo-Identification and Location of Marine Species. Animals, 16(2), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020281