Early-Onset Negative Energy Balance in Transition Dairy Cows Increases the Incidence of Retained Fetal Membranes

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Housing and Experimental Design

2.2. Phenotypic Indicators of Dairy Cows

2.2.1. Body Weight and Dry Matter Intake (DMI)

2.2.2. Body Temperature

2.2.3. Respiratory Rate

2.2.4. Step Count

2.3. Plasmic Biochemical Analyses and Metabolomic Profiling

2.3.1. Blood Sampling Protocol

2.3.2. Plasmic Biochemical Analyses

2.3.3. Plasmic Metabolome

2.4. Metabolomics Analysis of Placenta and Fetal Membrane

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Characteristic of RFM Dairy Cow

3.2. Plasmic Biochemical Indicators of RFM Dairy Cows

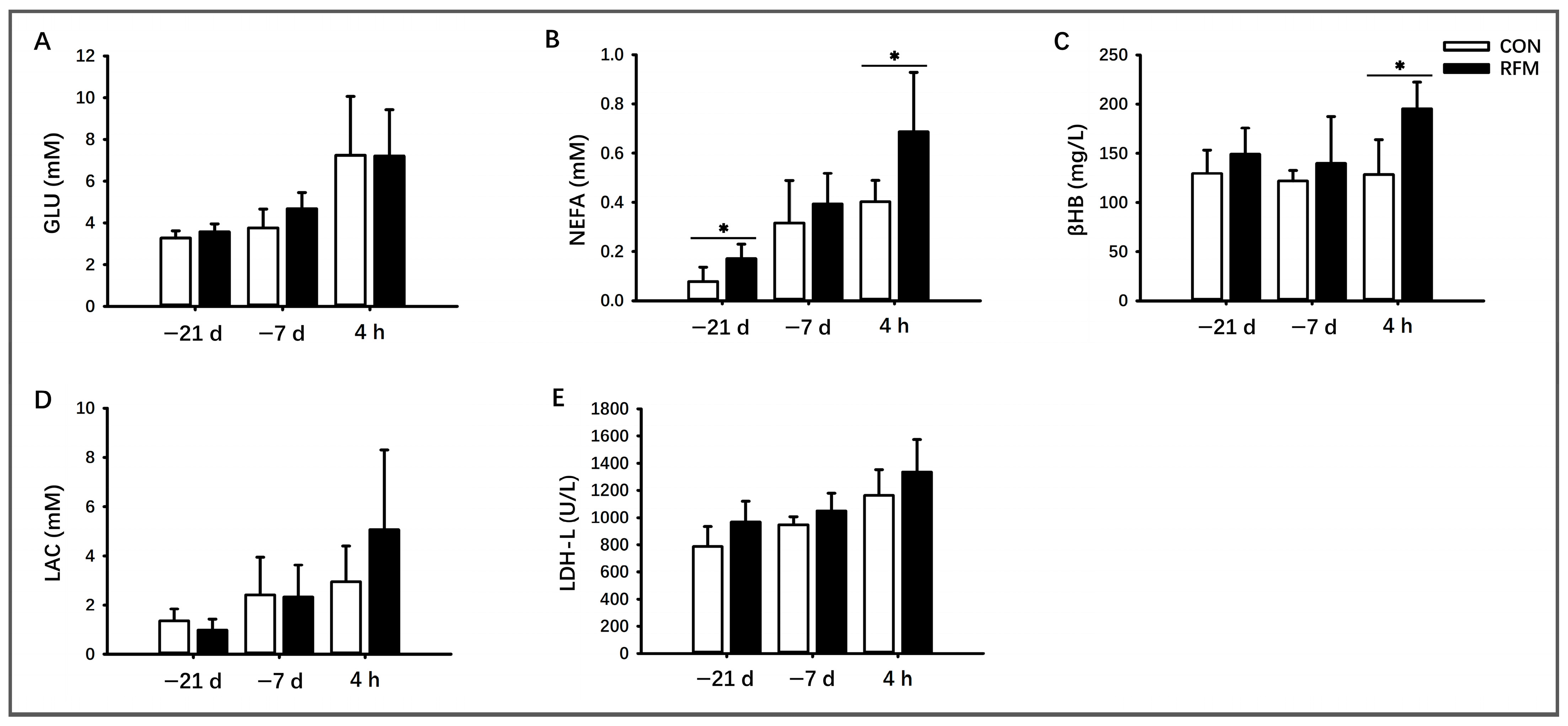

3.2.1. Lipid Mobilization

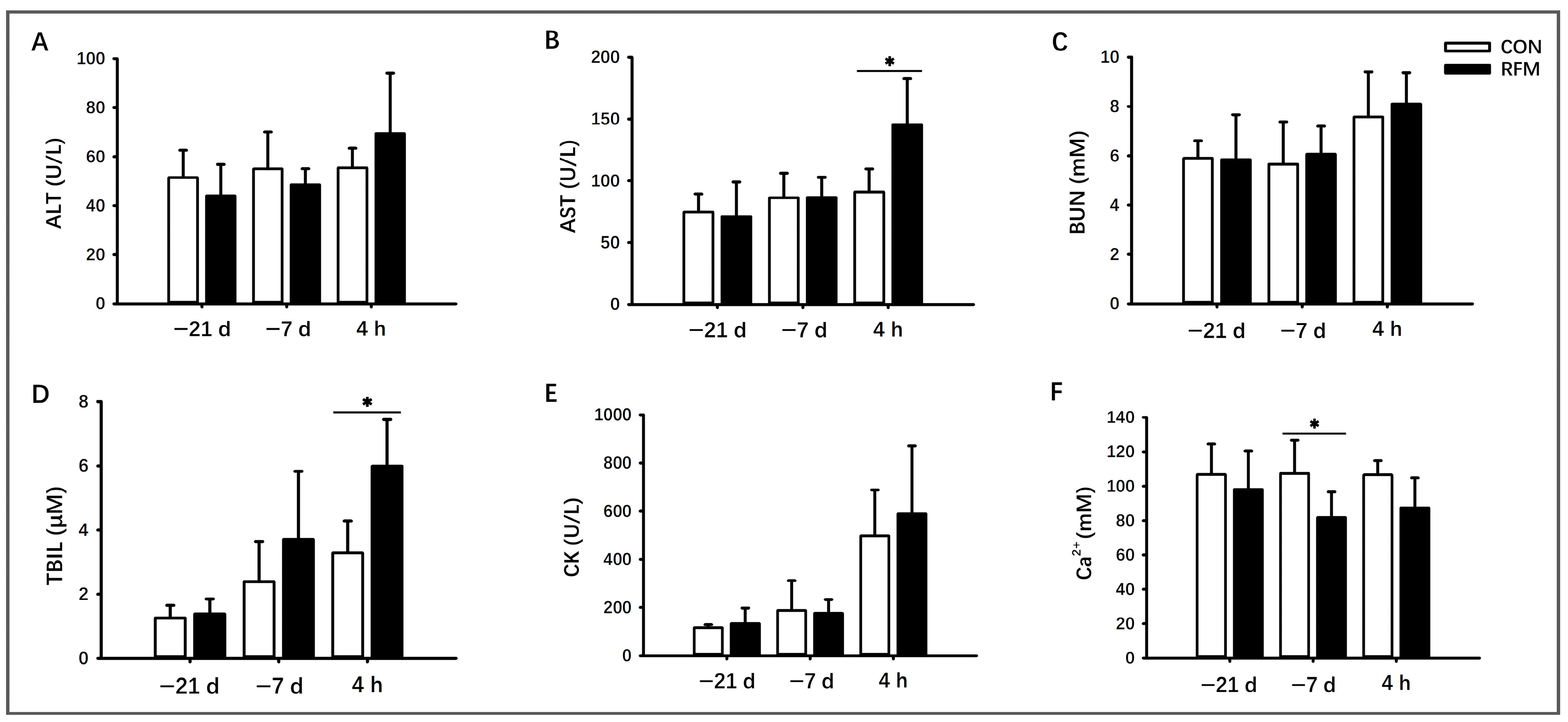

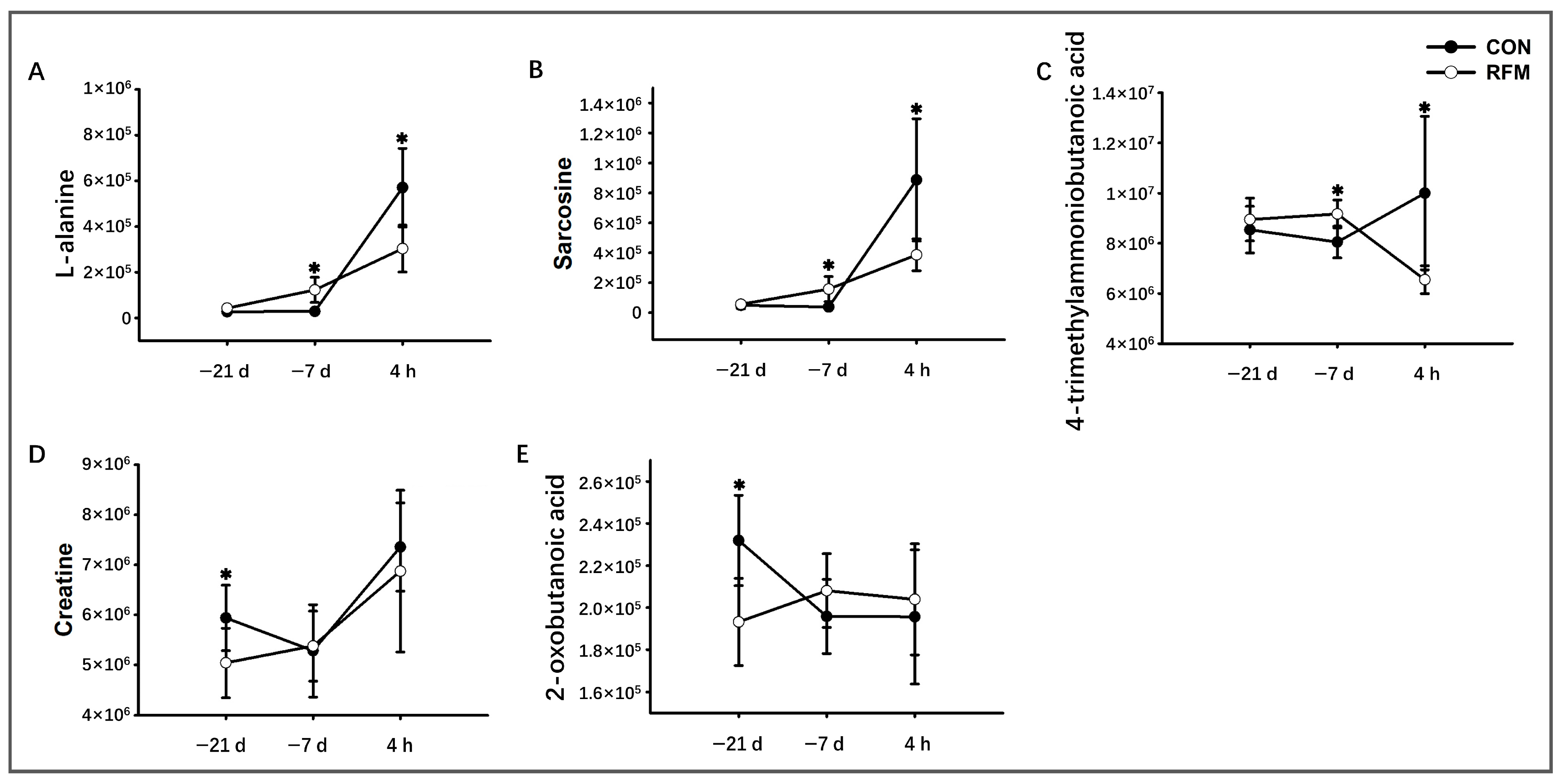

3.2.2. Muscle Tissue Mobilization

3.2.3. Plasma Ca2+ Dynamics

3.2.4. Antioxidant Ability

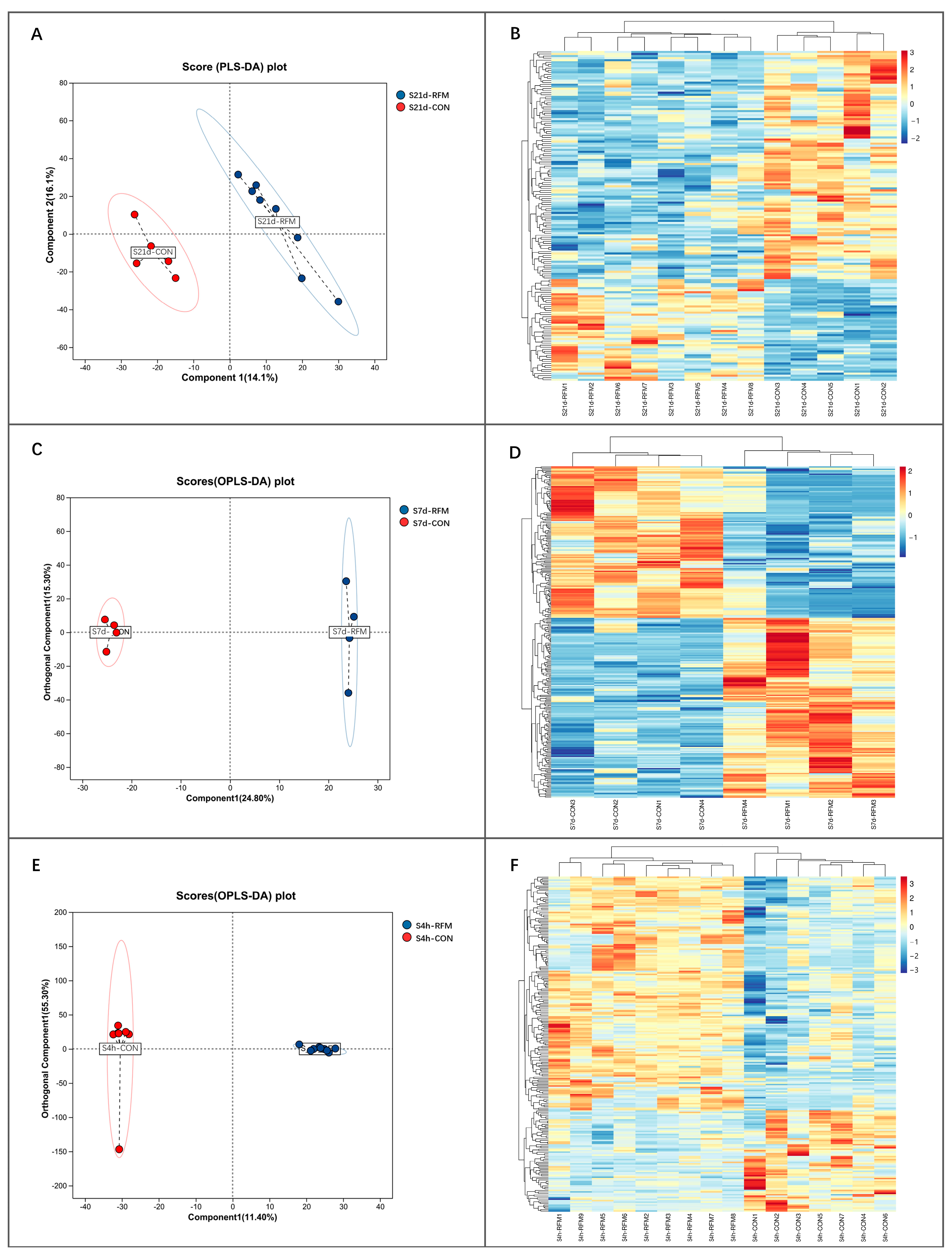

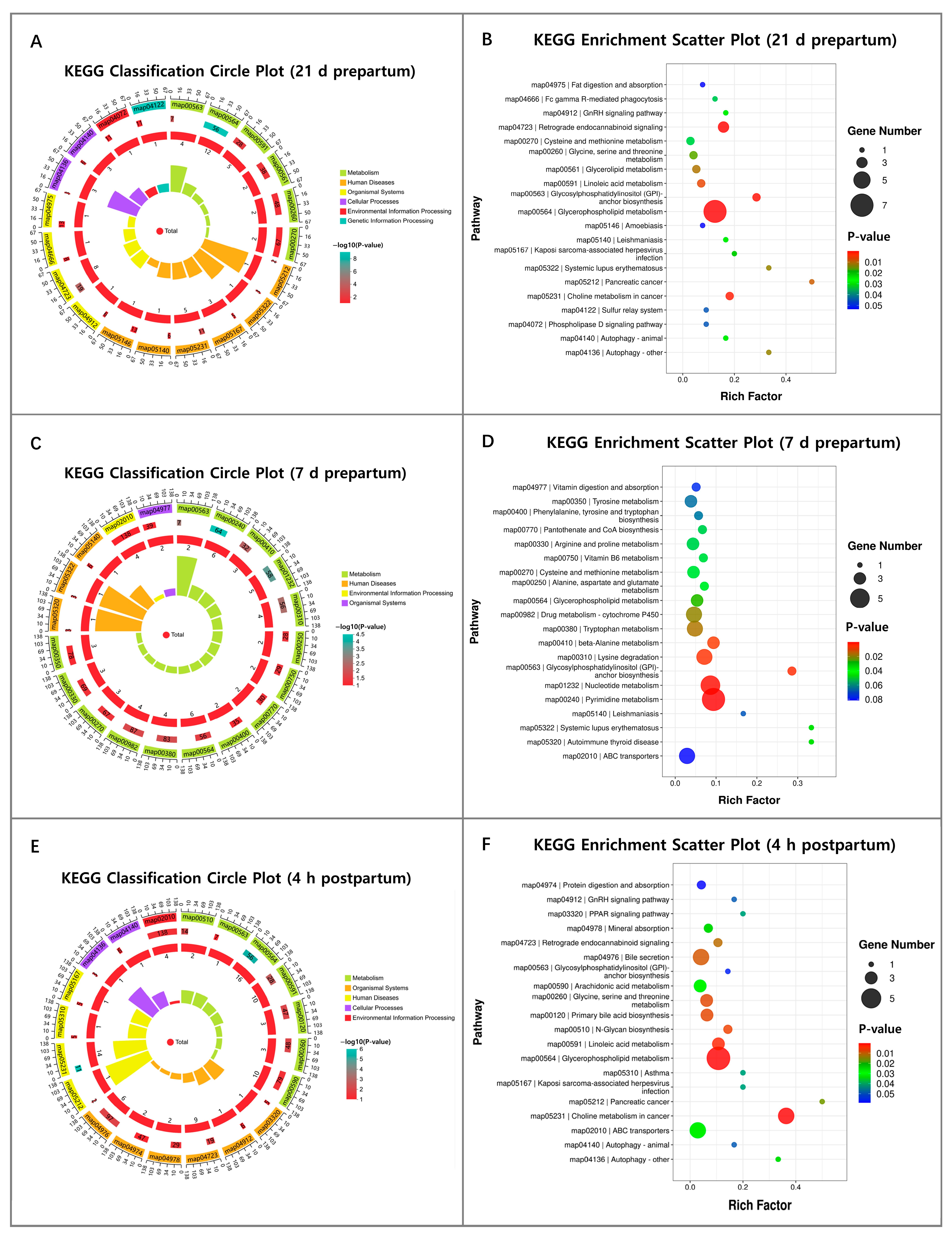

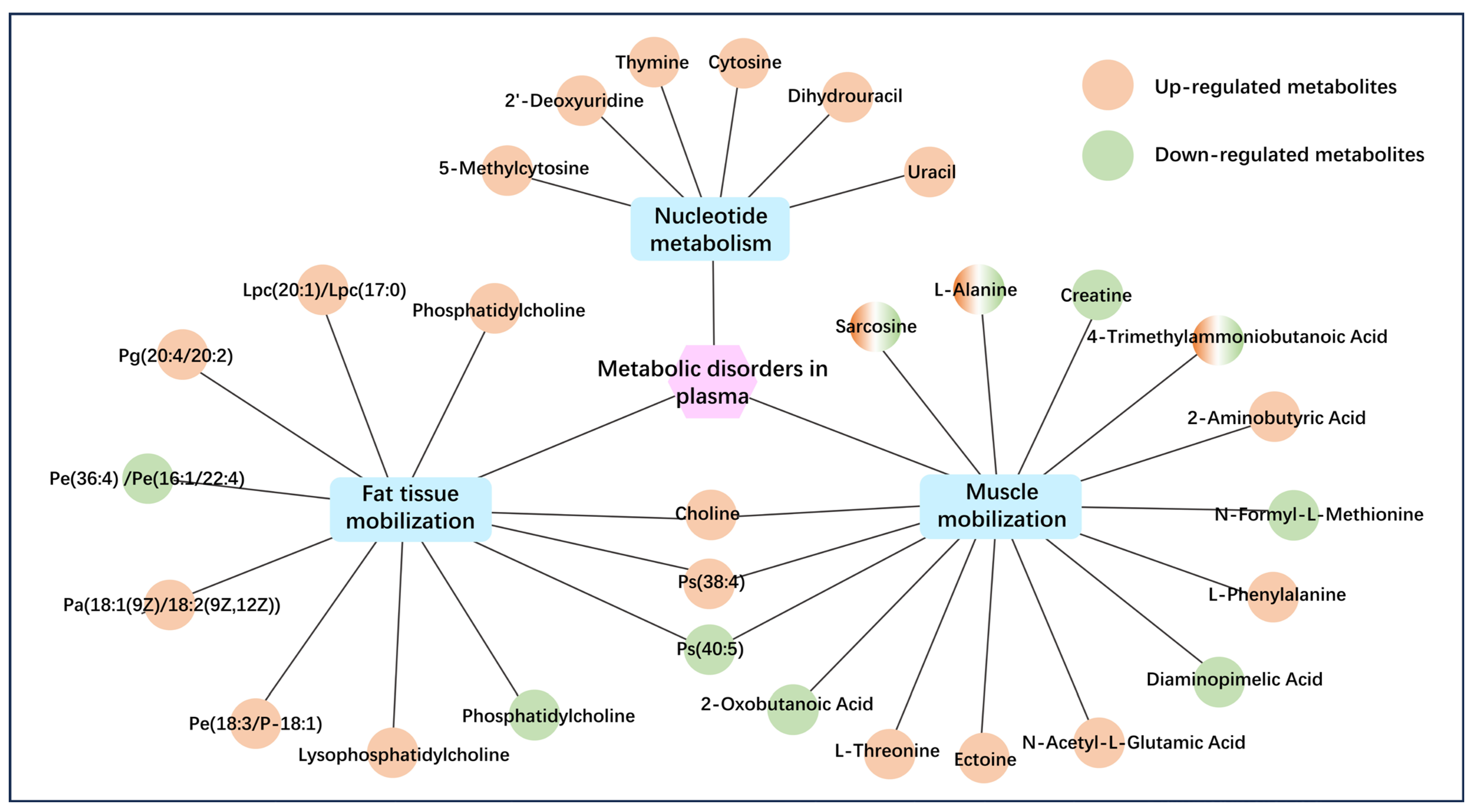

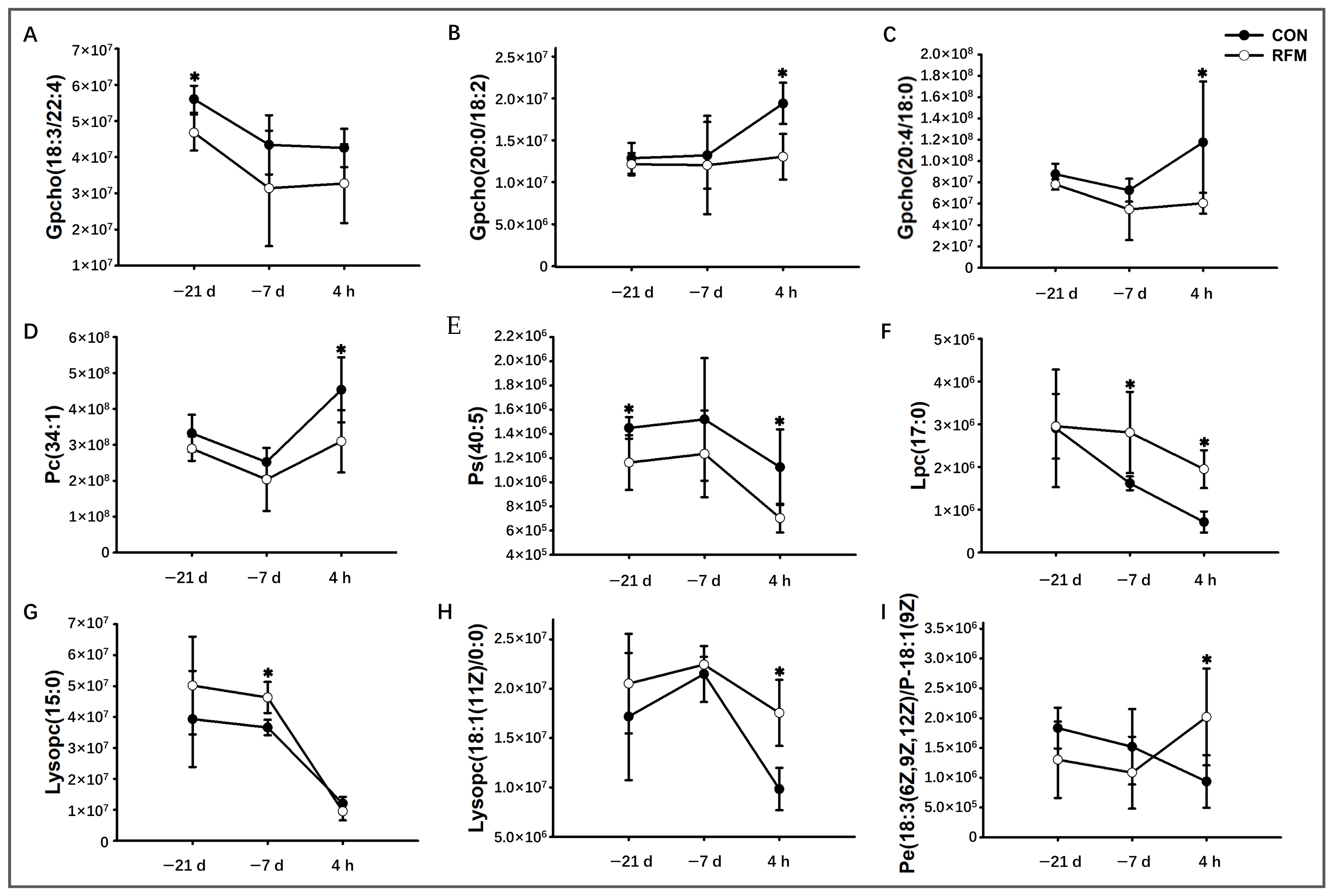

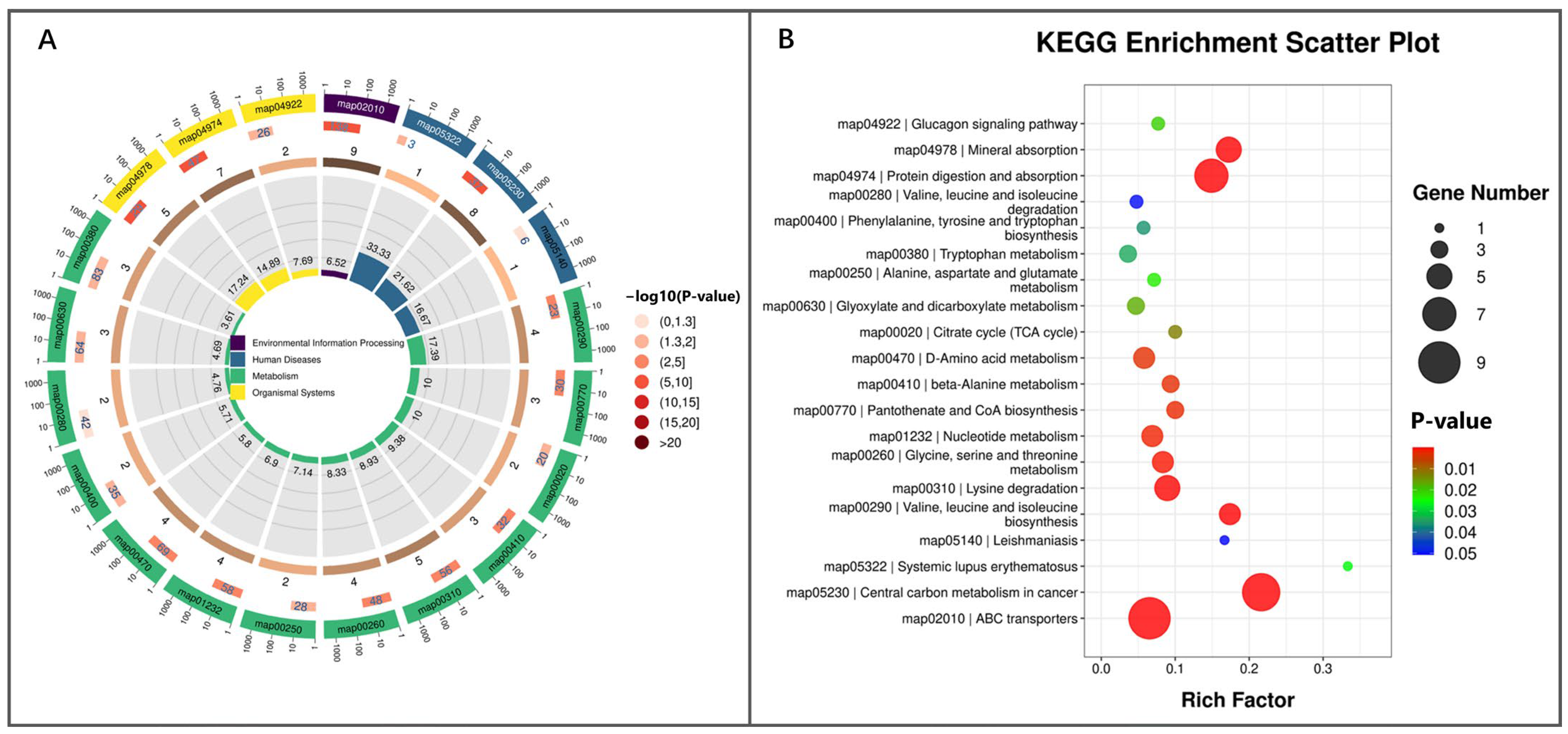

3.3. Plasma Metabolome Alteration of RFM Dairy Cow During the Peripartum Period

3.4. Metabolomic Analysis of RFM Dairy Cows’ Placenta and Fetal Membrane

3.4.1. Metabolomic Analysis of Placenta

3.4.2. Metabolomic Analysis of Fetal Membranes

3.4.3. The Correlation Between DMs and Metabolic Dysfunction in Placenta and Fetal Membranes of RFM Dairy Cows

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RFM | retained fetal membranes |

| NEB | negative energy balance |

| DMI | dry matter intake |

| GLU | glucose |

| NEFA | non-esterified fatty acid |

| βHB | β-hydroxybutyric acid |

| LAC | lactic acid |

| LDH | lactic dehydrogenase |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| CK | creatine kinase |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| TBIL | total bilirubin |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| GSH-Px | glutathione peroxidase |

| CAT | catalase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| PLS-DA | Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| DMs | differential metabolites |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Gpcho | phosphatidylcholines |

| Pc | Phosphatidylcholine |

| Ps | Phosphatidylserine |

| Dg | diacylglycerols |

References

- Attupuram, N.M.; Kumaresan, A.; Narayanan, K.; Kumar, H. Cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in placental separation in the bovine: A review. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2016, 83, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnani, A.; Sadeghi-Sefidmazgi, A.; Ansari-Mahyari, S.; Ghorbani, G.R. Assessing the consequences and economic impact of retained placenta in Holstein dairy cattle. Theriogenology 2021, 175, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, E.P.; Christley, R.M.; Dobson, H. Effects of periparturient events on subsequent culling and fertility in eight UK dairy herds. Vet. Rec. 2012, 170, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melendez, P.; Marin, M.P.; Robles, J.; Rios, C.; Duchens, M.; Archbald, L. Relationship between serum nonesterified fatty acids at calving and the incidence of periparturient diseases in Holstein dairy cows. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Y.A.; Hussein, H.A. Latest update on predictive indicators, risk factors and ‘Omic’ technologies research of retained placenta in dairy cattle—A review. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2022, 57, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsanollah, S.; Pouya, R.; Risco, C.A.; Hernandez, J.A. Observed and expected combined effects of metritis and other postpartum diseases on time to conception and rate of conception failure in first lactation cows in Iran. Theriogenology 2021, 164, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Arnold, L.M.; Stowe, C.J.; Harmon, R.J.; Bewley, J.M. Estimating US dairy clinical disease costs with a stochastic simulation model. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 1472–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohary, K.; LeBlanc, S.J. Cost of retained fetal membranes for dairy herds in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2018, 252, 1485–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Haeger, J.D.; Hambruch, N.; Pfarrer, C. The bovine placenta in vivo and in vitro. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boos, A.; Stelljes, A.; Kohtes, J. Collagen types I, III and IV in the placentome and interplacentomal maternal and fetal tissues in normal cows and in cattle with retention of fetal membranes. Cells Tissues Organs 2003, 174, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, A.T. Bovine placenta: A review on morphology, components, and defects from terminology and clinical perspectives. Theriogenology 2013, 80, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.A.; Bazer, F.W.; Seo, H.; Burghardt, R.C.; Wu, G.; Pohler, K.G.; Cain, J.W. Understanding placentation in ruminants: A review focusing on cows and sheep. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2023, 36, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streyl, D.; Kenngott, R.; Herbach, N.; Wanke, R.; Blum, H.; Sinowatz, F.; Wolf, E.; Zerbe, H.; Bauersachs, S. Gene expression profiling of bovine peripartal placentomes: Detection of molecular pathways potentially involved in the release of foetal membranes. Reproduction 2012, 143, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, A.P.; Murray, R.D. Structure and function of the bovine fetomaternal unit in relation to the causes of retained fetal membranes. Vet. Rec. 2009, 165, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, J.F. The effect of nutritional management of the dairy cow on reproductive efficiency. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2006, 96, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafa, H.; Oroian, I.; Cozma, O.M.; Morohoschi, A.G.; Dumitras, D.A.; Ștefănuț, C.L.; Neagu, D.; Borzan, A.; Andrei, S. Peripartal changes of metabolic and hormonal parameters in Romanian spotted cows and their relation with retained fetal membranes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1409666. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiamadis, V.; Panousis, N.; Siachos, N.; Gelasakis, A.I.; Banos, G.; Kougioumtzis, A.; Arsenos, G.; Valergakis, G.E. Subclinical hypocalcaemia follows specific time-related and severity patterns in post-partum Holstein cows. Animal 2021, 15, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huzzey, J.M.; Nydam, D.V.; Grant, R.J.; Overton, T.R. Associations of prepartum plasma cortisol, haptoglobin, fecal cortisol metabolites, and nonesterified fatty acids with postpartum health status in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5878–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, I.; Barca, J.; Pereira, I.; Meikle, A.; Ruprechter, G. Association between non-esterified fatty acids and calcium concentrations at calving with early lactation clinical diseases, fertility and culling in grazing dairy cows in Uruguay. Prev. Vet. Med. 2024, 230, 106294. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, G.A.; Strieder-Barboza, C.; Raphael, W. Adipose tissue lipolysis and remodeling during the transition period of dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venjakob, P.L.; Neuhaus, L.K.; Heuwieser, W.; Borchardt, S. Associations between time in the close-up group and milk yield, milk components, reproductive performance, and culling of Holstein dairy cows fed acidogenic diets: A multisite study. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 6858–6869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufarelli, V.; Puvača, N.; Glamočić, D.; Pugliese, G.; Colonna, M.A. The Most Important Metabolic Diseases in Dairy Cattle during the Transition Period. Animals 2024, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.; Nydam, D.V.; Abuelo, A.; Leal Yepes, F.A.; Overton, T.R.; Wakshlag, J.J. Insulin signaling, inflammation, and lipolysis in subcutaneous adipose tissue of transition dairy cows either overfed energy during the prepartum period or fed a controlled-energy diet. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 6737–6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, H. Invited Review: Increasing Milk Yield and Negative Energy Balance: A Gordian Knot for Dairy Cows? Animals 2023, 13, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascottini, O.B.; LeBlanc, S.J. Modulation of immune function in the bovine uterus peripartum. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotas, M.E.; Medzhitov, R. Homeostasis, inflammation, and disease susceptibility. Cell 2015, 160, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Chang, J.; Yao, W.; Qian, W.; Bai, Y.; Fu, S.; Xia, C. Mechanism of collagen type IV regulation by focal adhesion kinase during retained fetal membranes in dairy cows. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilly, M.; Hambruch, N.; Shenavai, S.; Schuler, G.; Froehlich, R.; Haeger, J.D.; Ozalp, G.R. Pfarrer C: Expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-14 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP)-2 during bovine placentation and at term with or without placental retention. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, K.M.; Ortega, M.S.; Johnson, G.A.; Seo, H.; Spencer, T.E. Review: Implantation and placentation in ruminants. Animal 2023, 17, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, J.P. Major advances in our understanding of nutritional influences on bovine health. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, R.; Rosic, N.; Beer, L.B.; Vince, S. Effects of Summer Heat on Adipose Tissue Activity in Periparturient Simmental Cows. Metabolites 2024, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.J.; Piersanti, R.L.; Ramirez-Hernandez, R.; de Oliveira, E.B.; Bishop, J.V.; Hansen, T.R.; Ma, Z.; Jeong, K.C.C.; Santos, J.E.P.; Sheldon, M.I. Experimentally Induced Endometritis Impairs the Developmental Capacity of Bovine Oocytes†. Biol. Reprod. 2020, 103, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubner, A.; Canisso, I.F.; Peixoto, P.M.; Coelho, W.M.; Ribeiro, L.; Aldridge, B.M.; Menta, P.; Machado, V.S.; Lima, F.S. Characterization of metabolic profile, health, milk production, and reproductive outcomes of dairy cows diagnosed with concurrent hyperketonemia and hypoglycemia. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9054–9069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raboisson, D.; Mounié, M.; Maigné, E. Diseases, reproductive performance, and changes in milk production associated with subclinical ketosis in dairy cows: A meta-analysis and review. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 7547–7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, S. Monitoring metabolic health of dairy cattle in the transition period. J. Reprod. Dev. 2010, 56, S29–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, N.; Risco, C.A.; Lima, F.S.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Greco, L.F.; Ribeiro, E.S.; Maunsell, F.; Galvão, K.; Santos, J.E. Evaluation of peripartal calcium status, energetic profile, and neutrophil function in dairy cows at low or high risk of developing uterine disease. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 7158–7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guo, H.; Yang, W.; Li, M.; Zou, Y.; Loor, J.J.; Xia, C.; Xu, C. Effects of ORAI calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1 (ORAI1) on neutrophil activity in dairy cows with subclinical hypocalcemia1. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 3326–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Engelen, E.; de Groot, M.W.; Breeveld-Dwarkasing, V.N.; Everts, M.E.; van der Weyden, G.C.; Taverne, M.A.; Rutten, V.P. Cervical ripening and parturition in cows are driven by a cascade of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009, 44, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankofer, M. The levels of lipid peroxidation products in bovine retained and not retained placenta. Prostag. Leukotr. ESS 2001, 64, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedernera, M.; Celi, P.; García, S.C.; Salvin, H.E.; Barchia, I.; Fulkerson, W.J. Effect of diet, energy balance and milk production on oxidative stress in early-lactating dairy cows grazing pasture. Vet. J. 2010, 186, 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Sordillo, L.M.; Raphael, W. Significance of metabolic stress, lipid mobilization, and inflammation on transition cow disorders. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2013, 29, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džermeikaitė, K.; Krištolaitytė, J.; Sutkevičienė, N.; Vilkonienė, T.; Vaičiulienė, G.; Rekešiūtė, A.; Girdauskaitė, A.; Arlauskaitė, S.; Bajcsy, Á.C.; Antanaitis, R. Relationships Among In-Line Milk Fat-to-Protein Ratio, Metabolic Profile, and Inflammatory Biomarkers During Early Stage of Lactation in Dairy Cows. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonekura, S. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in metabolic diseases and mammary epithelial cell homeostasis in dairy cows. Anim. Sci. J. 2024, 95, e13935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Kong, Y.; Li, B.; Zhao, C.; Loor, J.J.; Tan, P.; Yuan, Y.; Zeng, F.; Zhu, X.; Qi, S.; et al. Effects of perinatal stress on the metabolites and lipids in plasma of dairy goats. Stress Biol. 2023, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Rahman, A.; Chen, M.; Li, N.; Wu, T.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, N.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J. Rumen microbiota succession throughout the perinatal period and its association with postpartum production traits in dairy cows: A review. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 18, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluck, A.C.; Macagnan, R.; Skonieski, F.R.; Costa, O.A.D.; Cardinal, K.M.; Borba, L.P.d.; Schmitz, B.; Fischer, V. Is there an appropriate energy level in the diet during the cow transition period? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dairy Res. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummer, R.R. Etiology of Lipid-Related Metabolic Disorders in Periparturient Dairy Cows. J. Dairy S. 1993, 76, 3882–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drackley, J.K. ADSA Foundation Scholar Award. Biology of dairy cows during the transition period: The final frontier? J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 2259–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, H.A.; Rhyaf, A.G.; Alyasari, N.K.H.; Al-Karagoly, H. Assessing Serum Vaspin Dynamics in Dairy Cows during Late Pregnancy and Early Lactation in Relation to Negative Energy Balance. Dairy 2024, 5, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, J.W. Review: Lipid biology in the periparturient dairy cow: Contemporary perspectives. Animal 2020, 14, s165–s175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.R.; Zhao, H.Y.; Li, L.L.; Tan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.C.; Jiang, L.S. Metabolic lipid alterations in subclinical ketotic dairy cows: A multisample lipidomic approach. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 8887–8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kang, J.H.; Bae, Y.-S. The role and regulation of phospholipase D in metabolic disorders. Adv. Biol. Reg. 2024, 91, 100988. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, M.I.; Wang, Y.; Wakelam, M.J.O.; Bankaitis, V.A. Mammalian phospholipase D: Function, and therapeutics. Prog. Lip. Res. 2020, 78, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervishi, E.; Zhang, G.; Mandal, R.; Wishart, D.S.; Ametaj, B.N. 043 Metabolomics uncovers serum biomarkers that can predict the risk of retained placenta in transition dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Tymoczko, J.L. Stryer L: Phospholipid Metabolism. In Biochemistry, 9th ed.; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sadri, H.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Sauerwein, H. Invited review: Muscle protein breakdown and its assessment in periparturient dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 822–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, H.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Sauerwein, H.; Schuchardt, S.; Martín-Tereso, J.; Doelman, J.; Daniel, J.B. Longitudinal characterization of the muscle metabolome in dairy cows during the transition from lactation cessation to lactation resumption. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 1062–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouveia, K.M.; Beckett, L.M.; Casey, T.M.; Boerman, J.P. Production responses of multiparous dairy cattle with differing prepartum muscle reserves and supplementation of branched-chain volatile fatty acids. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 11655–11668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wen, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, H.; Li, H.; Huang, M. Potential prognostic markers of retained placenta in dairy cows identified by plasma metabolomics coupled with clinical laboratory indicators. Vet. Quart. 2022, 42, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, A.N.; Fan, T.W. Regulation of mammalian nucleotide metabolism and biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 2466–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, S.; Rafa, H.; Oroian, I.; Cozma, O.M.; Morohoschi, A.G.; Dumitraș, D.A.; Dulf, F.; Ștefănuț, C.L. The Interplay between Oxidative Stress and Fatty Acids Profile in Romanian Spotted Cows with Placental Retention. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 499. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Long, M.; Guo, Y. Effects of non-esterified fatty acids on relative abundance of prostaglandin E2 and F2α synthesis-related mRNA transcripts and protein in endometrial cells of cattle in vitro. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 221, 106549. [Google Scholar]

- Chankeaw, W.; Lignier, S.; Richard, C.; Ntallaris, T.; Raliou, M.; Guo, Y.; Plassard, D.; Bevilacqua, C.; Sandra, O.; Andersson, G. Analysis of the transcriptome of bovine endometrial cells isolated by laser micro-dissection (2): Impacts of post-partum negative energy balance on stromal, glandular and luminal epithelial cells. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 450. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; van Knegsel, A.; Saccenti, E.; van Hoeij, R.; Kemp, B.; Vervoort, J. Metabolomics of Milk Reflects a Negative Energy Balance in Cows. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 2942–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.; van Dorland, H.A.; Bruckmaier, R.M.; Schwarz, F.J. Performance and metabolic profile of dairy cows during a lactational and deliberately induced negative energy balance with subsequent realimentation. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Vervoort, J.; Saccenti, E.; Kemp, B.; van Hoeij, R.J.; van Knegsel, A.T.M. Relationship between energy balance and metabolic profiles in plasma and milk of dairy cows in early lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 4795–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, D.G.; Waters, S.M.; McCarthy, S.D.; Patton, J.; Earley, B.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Murphy, J.J.; Diskin, M.G.; Kenny, D.A.; Brass, A.; et al. Pleiotropic effects of negative energy balance in the postpartum dairy cow on splenic gene expression: Repercussions for innate and adaptive immunity. Physiol. Genom. 2009, 39, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, J.; Janowski, T. Expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα in the retained placenta of mares. Theriogenology 2019, 126, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Yu, Y.L. The interconnected roles of TRIM21/Ro52 in systemic lupus erythematosus, primary Sjögren’s syndrome, cancers, and cancer metabolism. Cancer Cell Inter. 2023, 23, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervishi, E.; Zhang, G.; Hailemariam, D.; Dunn, S.M.; Ametaj, B.N. Occurrence of retained placenta is preceded by an inflammatory state and alterations of energy metabolism in transition dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechno. 2016, 7, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Jamioł, M.; Wawrzykowski, J.; Mojsym, W.; Hoedemaker, M.; Kankofer, M. Activity of selected glycosidases and availability of their substrates in bovine placenta during pregnancy and parturition with and without retained foetal membranes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2020, 55, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beagley, J.C.; Whitman, K.J.; Baptiste, K.E.; Scherzer, J. Physiology and Treatment of Retained Fetal Membranes in Cattle. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items 1 | Ingredients and Chemical Composition |

|---|---|

| Ingredient | |

| Corn silage | 38.72 |

| Oat hay | 24.34 |

| Beet pulp | 6.49 |

| Rolled corn | 4.06 |

| Soybean meal | 22.71 |

| Yeast | 0.16 |

| Choline chloride | 0.28 |

| Vitamin-mineral mix | 3.24 |

| Nutrient composition | |

| DM, % | 48.0 |

| NEL 2, Mcal/kg DM | 1.5 |

| CP, % of DM | 15.8 |

| Starch, % of DM | 15.0 |

| NDF, % of DM | 36.2 |

| ADF, % of DM | 21.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Guo, S.; Yang, J.; Hou, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Jin, Y. Early-Onset Negative Energy Balance in Transition Dairy Cows Increases the Incidence of Retained Fetal Membranes. Animals 2026, 16, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020229

Zhang Z, Guo S, Yang J, Hou X, Zhang X, Liu H, Liu T, Jin Y. Early-Onset Negative Energy Balance in Transition Dairy Cows Increases the Incidence of Retained Fetal Membranes. Animals. 2026; 16(2):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020229

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhihong, Shanshan Guo, Jianhao Yang, Xinfeng Hou, Xia Zhang, Huifeng Liu, Tao Liu, and Yaping Jin. 2026. "Early-Onset Negative Energy Balance in Transition Dairy Cows Increases the Incidence of Retained Fetal Membranes" Animals 16, no. 2: 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020229

APA StyleZhang, Z., Guo, S., Yang, J., Hou, X., Zhang, X., Liu, H., Liu, T., & Jin, Y. (2026). Early-Onset Negative Energy Balance in Transition Dairy Cows Increases the Incidence of Retained Fetal Membranes. Animals, 16(2), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020229