The Effects of Reduced Glutathione on Growth Performance, Intestinal Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota in Immune-Stressed Broiler Chickens

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Animal Feeding Management

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Growth Performance

2.4. Intestinal Inflammation

2.5. Expression Levels of TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway-Related Factors

2.6. Analysis of Gut Microbiota

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

3.2. Immunoglobulin and Inflammatory Factor Content

3.3. Expression Levels of TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway Related Factors

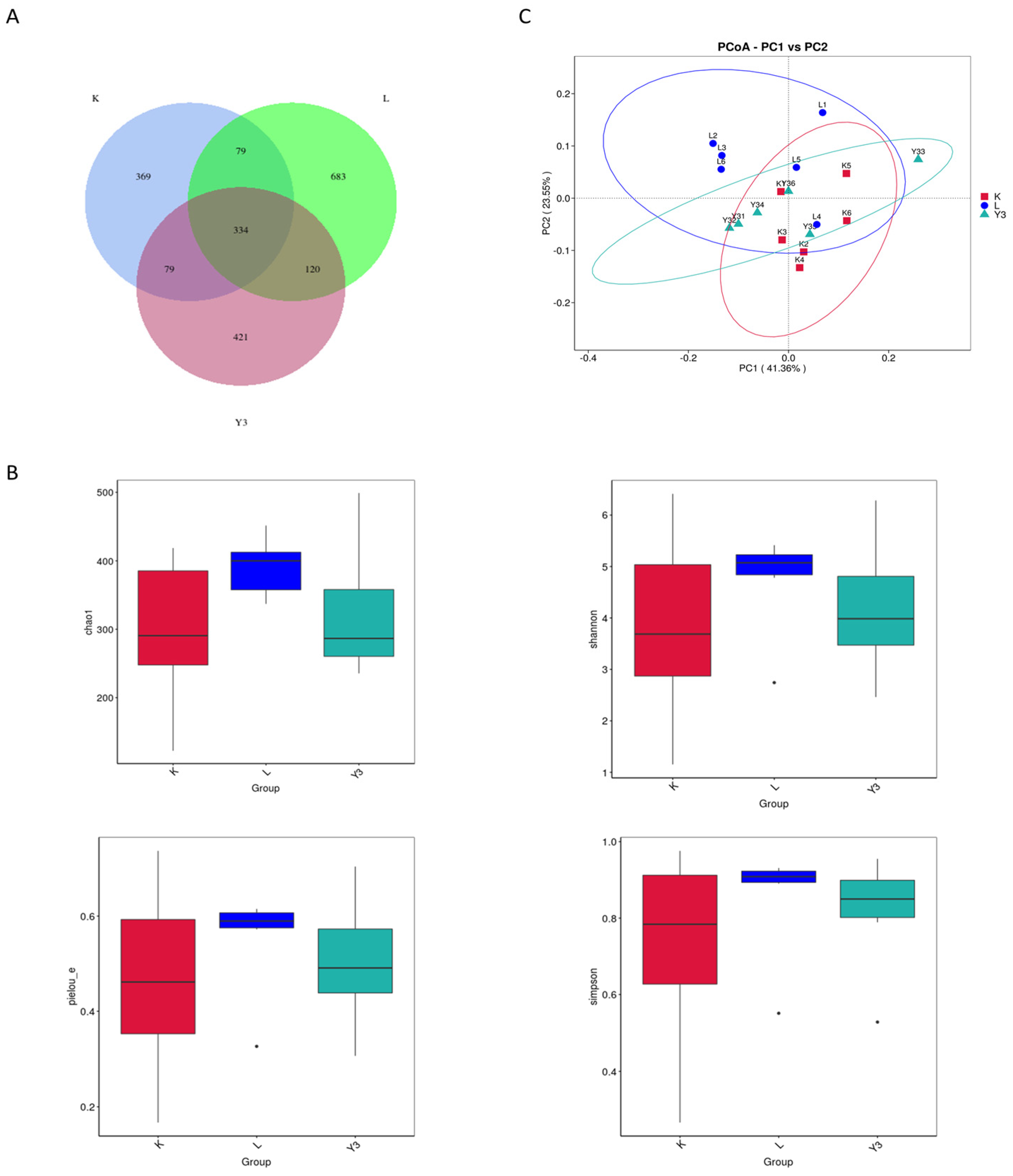

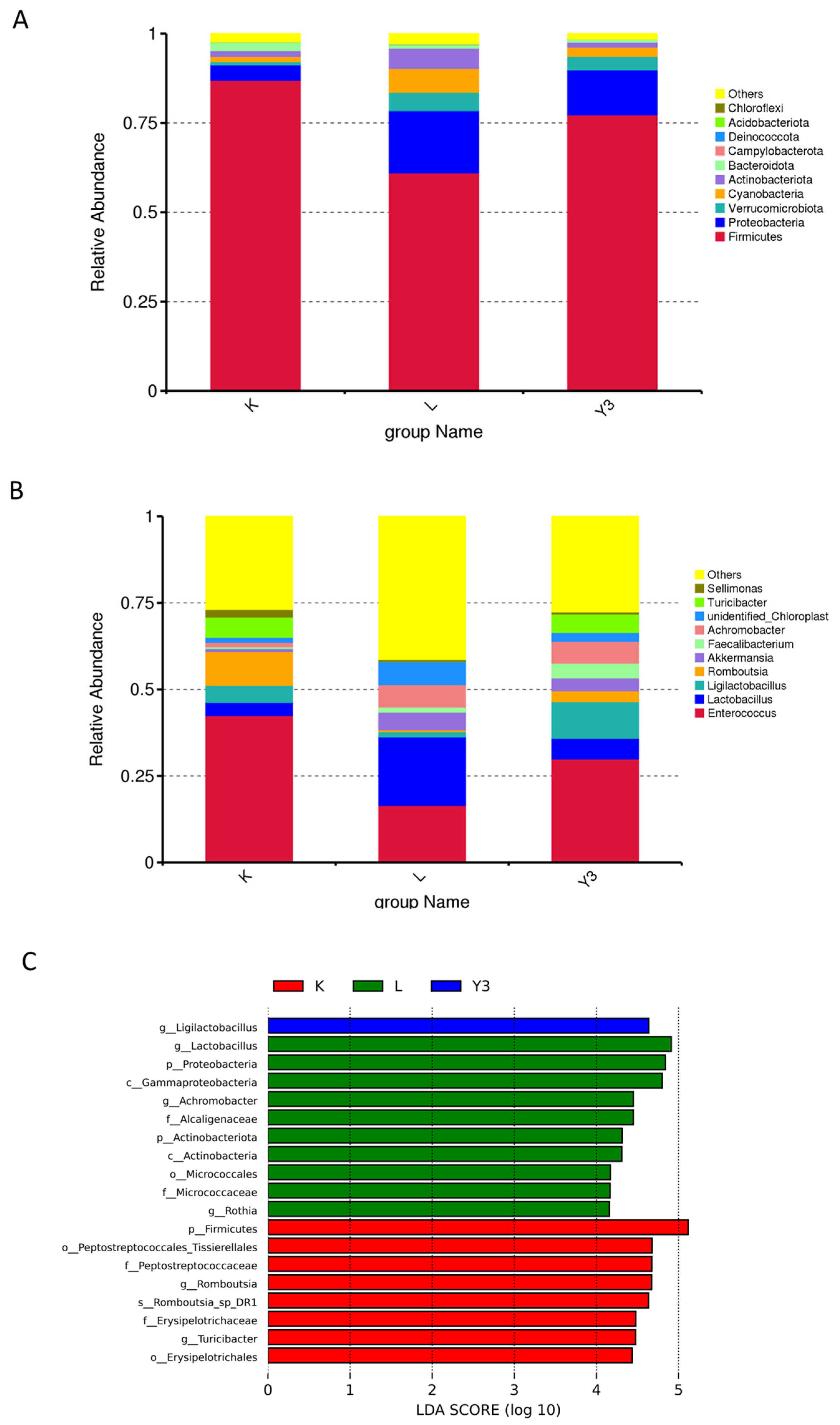

3.4. Intestinal Microbiota Community

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GSH | glutathione |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| ADG | average daily gain |

| ADFI | average daily feed intake |

| F/G | average daily feed intake/average daily gain |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-B |

| TLR4 | toll-like receptor 4 |

References

- Liu, H.; Meng, H.; Du, M.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K. Chlorogenic acid ameliorates intestinal inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB and endoplasmic reticulum stress in lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, K.; Allen-Vercoe, E. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: Major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome 2019, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2015, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Hao, R.; Li, J. Effects of high fructose corn syrup on intestinal microbiota structure and obesity in mice. npj Sci. Food 2022, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, A.; Manzanilla, E.G.; Díaz, J.A.C.; Leonard, F.C.; A Boyle, L. Do weaner pigs need in-feed antibiotics to ensure good health and welfare? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielen, S.; Trischler, J.; Schubert, R. Lipopolysaccharide challenge: Immunological effects and safety in humans. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 11, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mireles, A.J.; Kim, S.M.; Klasing, K.C. An acute inflammatory response alters bone homeostasis, body composition, and the humoral immune response of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Li, W.L.; Feng, Y.; Yao, J.H. Effects of immune stress on growth performance, immunity, and cecal microflora in chickens. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 2740–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, T.; Du, Y.; Xing, C.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, R.F. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling and Its Role in Cell-Mediated Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 812774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Lee, J.; Vu, T.H.; Lee, S.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Hong, Y.H. Exosomes of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated chicken macrophages modulate immune response through the MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021, 115, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Shao, Q.; Chen, W.; Ma, L.; Xu, W.; Li, Y.; Huang, S.; Ma, Y. Effects of Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide in diet on growth performance, serum antioxidant capacity, and biochemistry of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dringen, R.; Pfeiffer, B.; Hamprecht, B. Synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione in neurons: Supply by astrocytes of CysGly as precursor for neuronal glutathione. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Eady, S.J. Glutathione: Its implications for animal health, meat quality, and health benefits of consumers. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2005, 56, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.B.; Butterfield, D.A. Measurement of oxidized/reduced glutathione ratio. In Protein Misfolding and Cellular Stress in Disease and Aging; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 648, pp. 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B.; Vicenzi, M.; Garrel, C.; Denis, F.M. Effects of N-acetylcysteine, oral glutathione (GSH) and a novel sublingual form of GSH on oxidative stress markers: A comparative crossover study. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X. Glutathione regulates CIA-activated splenic lymphocytes via NF-κB/MMP-9 and MAPK/PCNA pathways manipulating immune response. Cell Immunol. 2024, 405–406, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhai, T.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, S.; Yang, H. Glutathione-responsive chemodynamic therapy of manganese (III/IV) cluster nanoparticles enhanced by electrochemical stimulation via oxidative stress pathway. Bioconjug. Chem. 2022, 33, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.; Federici, G.; Bertini, E.; Piemonte, F. Analysis of glutathione: Implication in redox and detoxification. Clin. Chim. Acta 2003, 333, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.Z.; Yang, S.; Wu, G. Free radicals, antioxidants, and nutrition. Nutrition 2002, 18, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Chen, S.; Ge, Y.; Guan, T.; Han, Y. Regulation of glutathione on growth performance, biochemical parameters, non-specific immunity, and related genes of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) exposed to ammonia. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, Y.M.; Wang, T. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens supplementation alleviates immunological stress in lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers at early age. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoc, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassahn, K.S.; Crozier, R.H.; Prtner, H.O.; Caley, M.J. Animal performance and stress: Responses and tolerance limits at different levels of biological organisation. Biol. Rev. 2010, 84, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, V.; Galgani, M.; Santopaolo, M.; Colamatteo, A.; Laccetti, R.; Matarese, G. Nutritional control of immunity: Balancing the metabolic requirements with an appropriate immune function. Semin. Immunol. 2015, 27, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, J.H.; Ye, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Xu, P.; Xie, J. Effects of dietary reduced glutathione on growth performance, non-specific immunity, antioxidant capacity and expression levels of IGF-I and HSP70 mRNA of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture 2015, 438, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.D.; Ma, G.; Cai, J.; Fu, Y.; Yan, X.Y.; Wei, X.B.; Zhang, R.J. Effects of Clostridium butyricum on growth performance, antioxidation, and immune function of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.T.; Coussens, L.M. Humoral immunity, inflammation and cancer. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007, 19, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V. Epithelial cell contributions to intestinal immunity. In Advances in Immunology; Alt, F.W., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 129–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.W.; Cavacini, L. Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, S41–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. LPS-induced inflammation disorders bone modeling and remodeling by inhibiting angiogenesis and disordering osteogenesis in chickens. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 69, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Gao, M.; Li, G.; Nie, W.; Xiao, L.; Lv, Z.; Guo, Y. Effects of Dietary Supplemental Chlorogenic Acid and Baicalin on the Growth Performance and Immunity of Broilers Challenged with Lipopolysaccharide. Life 2023, 13, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fang, X.; Niimi, M.; Huang, Y.; Piao, H.; Gao, S.; Fan, J.; Yao, J. Glutathione inhibits antibody and complement-mediated immunologic cell injury via multiple mechanisms. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.T.; Huang, L.; Pan, W.; Ren, Y.L. Antioxidant glutathione inhibits inflammation in synovial fibroblasts via PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway: An in vitro study. Arch. Rheumatol. 2022, 37, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.G.; Chen, R.; Wang, H.; Lin, L.M.; Xia, X.P. Cryptotanshinone inhibits prostaglandin E2 production and COX-2 expression via suppression of TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated Caco-2 cells. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 116, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.; von der Weid, P.Y. Lipopolysaccharides modulate intestinal epithelial permeability and inflammation in a species-specific manner. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilchovska, D.; Barrow, D.M. An overview of the NF-κB mechanism of pathophysiology in rheumatoid arthritis, investigation of the NF-κB ligand RANKL and related nutritional interventions. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhao, T.; Liu, L.; Jiao, H.; Lin, H. Effect of copper on antioxidant ability and nutrient metabolism in broiler chickens stimulated by lipopolysaccharides. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2011, 65, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.D.; Liu, W.B.; Zhang, D.D.; Xu, C.Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zheng, X.C.; Chi, C. Dietary reduced glutathione supplementation can improve growth, antioxidant capacity, and immunity on Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 100, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.J.; Harb, H.L. L-γ-Glutamyl-L-cysteinyl-glycine (glutathione; GSH) and GSH-related enzymes in the regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines: A signaling transcriptional scenario for redox(y) immunologic sensor(s)? Mol. Immunol. 2005, 42, 987–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portincasa, P.; Bonfrate, L.; Vacca, M.; De Angelis, M.; Farella, I.; Lanza, E.; Khalil, M.; Wang, D.Q.-H.; Sperandio, M.; Di Ciaula, A. Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids: Implications in Glucose Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, J.; Chang, E.B. The gut microbiota and inflammatory bowel diseases. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhya, I.; Hansen, R.; El-Omar, E.M.; Hold, G.L. IBD-what role do Proteobacteria play? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Yan, W.; Xu, J.; Song, Z.; Su, M.; Zeng, J.; Han, Q.; Ruan, G.; et al. Gut microbiota-derived glutathione from metformin treatment alleviates intestinal ferroptosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meimandipour, A.; Shuhaimi, M.; Soleimani, A.F.; Azhar, K.; Hair-Bejo, M.; Kabeir, B.M.; Javanmard, A.; Anas, O.M.; Yazid, A.M. Selected microbial groups and short-chain fatty acids profile in a simulated chicken cecum supplemented with two strains of Lactobacillus. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, K.; Isobe, J.; Hattori, K.; Hosonuma, M.; Baba, Y.; Murayama, M.; Narikawa, Y.; Toyoda, H.; Funayama, E.; Tajima, K.; et al. Turicibacter and Acidaminococcus predict immune-related adverse events and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1164724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Dhadi, S.R.; Mai, N.N.; Taylor, C.; Roy, J.W.; Barnett, D.A.; Lewis, S.M.; Ghosh, A.; Ouellette, R.J. The polysaccharide chitosan facilitates the isolation of small extracellular vesicles from multiple biofluids. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredient (%) | 0~21 d (%) | Nutrient Levels | 0~21 d (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 56.60 | (MJ/Kg) | 11.63 |

| Soybean meal | 26.20 | CP | 18.0 |

| Fish meal | 4.50 | CF | 6.00 |

| Limestone | 1.50 | Ash | 8.00 |

| Corn protein flour | 3.65 | Ca | 1.20 |

| Vegetable oil | 2.00 | AP | 0.60 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.00 | Met | 0.58 |

| DL-Met (99%) | 0.35 | H2O | 14.00 |

| NaCl | 0.4 | ||

| FeSO4 | 1.20 | ||

| CuSO4 | 1.10 | ||

| ZnSO4 | 0.87 | ||

| MnSO4 | 0.60 | ||

| Vitamin premix * | 0.03 | ||

| Total | 100 |

| Gene | Accession Number | Primer Sequences (5′→3′) | bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | NM_205518.2 | F: GCCAACAGAGAGAAGATGACACAG R: CATCACCAGAGTCCATCACAATACC | 133 |

| TNF-α | NM_204267.2 | F: TCAGGACAGCCTATGCCAACAAG R: TCACGATCATCTGGTTACAGGAAG | 127 |

| IL-1β | NM_204524.2 | F: GCCGAGGAGCAGGGACTTTG R: GAAGGACTGTGAGCGGGTGTAG | 136 |

| IL-2 | NM_204153.2 | F: CTCAAGAGTCTTACGGGTCTAAATCAC R: TCTCACAAAGTTGGTCAGTTCATGG | 111 |

| IL-6 | NM_204628.2 | F: GAAATCCCTCCTCGCCAATCTG R: CCTCACGGTCTTCTCCATAAACG | 106 |

| IFN-γ | NM_205149.2 | F: GCTGACGGTGGACCTATTATTGTAG R: GTTTGATGTGCGGCTTTGACTTG | 139 |

| NF-κB | NM_001396395.1 | F: GCCAACAGAGAGAAGATGACACAG R: CATCACCAGAGTCCATCACAATACC | 91 |

| TLR4 | NM_001030693.2 | F: CCATCCCAACCCAACCACAGTAG R: ACCCACTGAGCAGCACCAATG | 122 |

| Stage | Item | K | L | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | SEM | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–16 d | BW/g | 43.04 | 41.61 | 41.54 | 42.90 | 42.36 | 0.28 | 0.257 |

| 1–16 d | ADG/g | 22.56 bc | 21.00 c | 22.83 bc | 23.34 ab | 24.04 a | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| 1–16 d | ADFI/g | 41.76 | 40.92 | 41.07 | 39.74 | 41.17 | 2.47 | 1 |

| 1–16 d | BW/g | 381.45 bc | 377.30 c | 384.02 bc | 392.95 ab | 403.27 a | 2.07 | <0.001 |

| 1–16 d | F/G | 1.88 | 1.86 | 1.72 | 1.73 | 1.69 | 0.12 | 0.956 |

| 16–21 d | ADG/g | 34.93 a | 22.51 c | 23.32 c | 24.01 bc | 28.93 b | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| 16–21 d | ADFI/g | 94.50 b | 81.56 a | 84.97 a | 86.92 ab | 91.40 ab | 1.43 | 0.049 |

| 16–21 d | BW/g | 588.65 a | 498.75 d | 523.15 cd | 542.30 bc | 576.40 ab | 5.44 | <0.001 |

| 16–21 d | F/G | 2.76 b | 3.89 a | 3.56 ab | 3.66 ab | 3.25 ab | 0.3 | 0.027 |

| 1–21 d | ADG/g | 25.99 ab | 21.76 a | 22.88 ab | 23.80 bc | 25.40 c | 0.26 | <0.001 |

| 1–21 d | ADFI/g | 56.84 | 52.53 | 53.61 | 53.22 | 55.52 | 2.78 | 0.988 |

| 1–21 d | F/G | 2.24 | 2.48 | 2.40 | 2.30 | 2.20 | 0.12 | 0.877 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | L | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | |||

| sIgA (μg/mL) | 14.00 b | 11.62 c | 14.90 ab | 14.13 b | 16.10 a | 0.201 | <0.001 |

| IgM (μg/mL) | 540.46 c | 802 a | 729.98 b | 726.99 b | 590.67 c | 9.522 | <0.001 |

| IgG (μg/mL) | 2245.31 d | 2584.38 a | 2468.75 b | 2315.63 c | 2310.16 c | 3.29 | <0.001 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | L | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | |||

| IL-2 (p g/mL) | 226.50 b | 285.65 a | 269.31 a | 267.35 a | 231.73 b | 4.387 | 0.006 |

| IL-6 (p g/mL) | 26.4 a | 34.65 b | 31.25 ab | 30.84 ab | 30.24 ab | 0.669 | 0.024 |

| IL-4 (p g/mL) | 11.06 c | 12.61 a | 12.42 ab | 12.07 b | 10.62 d | 0.055 | <0.001 |

| IL-1β (p g/mL) | 909.48 d | 1340.52 a | 1246.55 b | 1018.53 c | 981.90 c | 7.17 | <0.001 |

| TNF-α (p g/mL) | 113.74 c | 128.34 a | 120.75 ab | 123.79 ab | 107.10 c | 1.835 | 0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, X.-Q.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.-K.; Li, H.-J.; Makatjane, K.A.; Lai, Z.; Bi, J.-X.; Zhou, H.-Z.; Guo, W. The Effects of Reduced Glutathione on Growth Performance, Intestinal Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota in Immune-Stressed Broiler Chickens. Animals 2026, 16, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020178

Wang X-Q, Zhang T, Liu Y-K, Li H-J, Makatjane KA, Lai Z, Bi J-X, Zhou H-Z, Guo W. The Effects of Reduced Glutathione on Growth Performance, Intestinal Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota in Immune-Stressed Broiler Chickens. Animals. 2026; 16(2):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020178

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xin-Qi, Tao Zhang, Ying-Kun Liu, Hao-Jia Li, Kabelo Anthony Makatjane, Zhen Lai, Jian-Xin Bi, Hai-Zhu Zhou, and Wei Guo. 2026. "The Effects of Reduced Glutathione on Growth Performance, Intestinal Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota in Immune-Stressed Broiler Chickens" Animals 16, no. 2: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020178

APA StyleWang, X.-Q., Zhang, T., Liu, Y.-K., Li, H.-J., Makatjane, K. A., Lai, Z., Bi, J.-X., Zhou, H.-Z., & Guo, W. (2026). The Effects of Reduced Glutathione on Growth Performance, Intestinal Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota in Immune-Stressed Broiler Chickens. Animals, 16(2), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020178