Protective Effects of Humic Acid on Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Inflammatory Activation in Canine Cell-Based Models

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

2.1.1. Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cell Line (IPEC-J2)

2.1.2. Canine Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

2.2. Humic Acid Extract Product Preparation

2.3. Inflammation Induction

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

2.5. Barrier Function (Paracellular Permeability) Assessment

2.6. Measurement of Intracellular ROS Levels

2.7. Cytokine Quantification in PBMC Supernatants

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Humic Acid Extract on Cell Viability

3.2. Effect of Humic Acid Extract on Intestinal Barrier Integrity

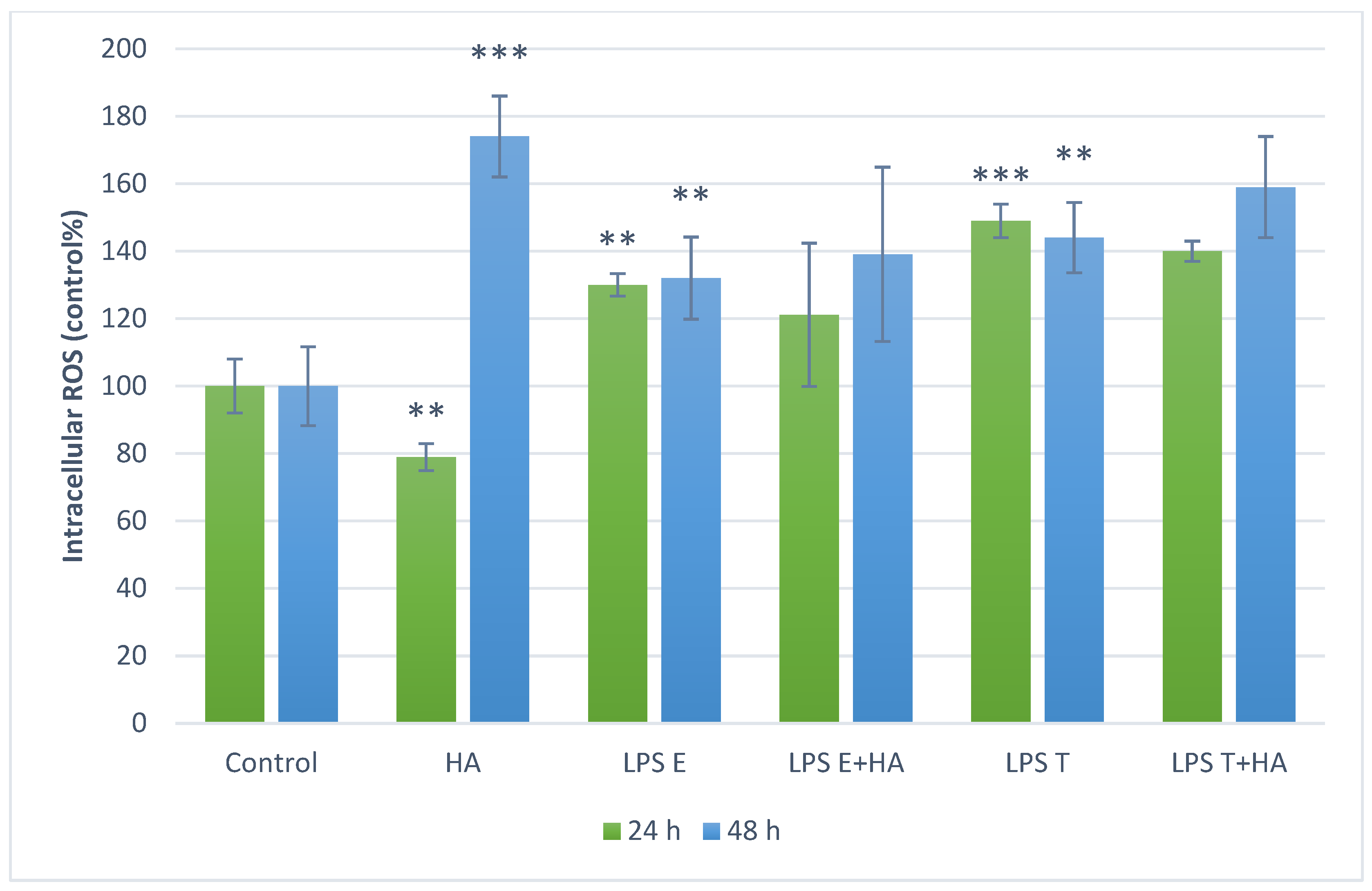

3.3. Measurement of Intracellular ROS Levels

3.4. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Humic Acid Extract on PBMC Cultures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghosh, S.S.; Wang, J.; Yannie, P.J.; Ghosh, S. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction, LPS Translocation, and Disease Development. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvz039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, M.F.; Artis, D.; Becker, C. The Intestinal Barrier: A Pivotal Role in Health, Inflammation, and Cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, P.; Saha, K.; Nighot, P. Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junction Barrier Regulation by Novel Pathways. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, G.; Barbaro, M.R.; Fuschi, D.; Palombo, M.; Falangone, F.; Cremon, C.; Marasco, G.; Stanghellini, V. Inflammatory and Microbiota-Related Regulation of the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 718356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulkens, J.; Vergauwen, G.; Van Deun, J.; Geeurickx, E.; Dhondt, B.; Lippens, L.; De Scheerder, M.-A.; Miinalainen, I.; Rappu, P.; De Geest, B.G.; et al. Increased Levels of Systemic LPS-Positive Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Patients with Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction. Gut 2020, 69, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, A.; Yan, F.; Polk, D.B.; Rao, R.K. Probiotics Ameliorate the Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Epithelial Barrier Disruption by a PKC- and MAP Kinase-Dependent Mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 294, G1060–G1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeckinghaus, A.; Ghosh, S. The NF-kappaB Family of Transcription Factors and Its Regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabal, M.; Calleja, D.J.; Simpson, D.S.; Lawlor, K.E. Stressing out the Mitochondria: Mechanistic Insights into NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 105, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D.K.; Heilmann, R.M.; Paital, B.; Patel, A.; Yadav, V.K.; Wong, D.; Jergens, A.E. Oxidative Stress, Hormones, and Effects of Natural Antioxidants on Intestinal Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1217165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenspach, K.; Mochel, J.P. Current Diagnostics for Chronic Enteropathies in Dogs. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 50, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matei, M.-C.; Andrei, S.M.; Buza, V.; Cernea, M.S.; Dumitras, D.A.; Neagu, D.; Rafa, H.; Popovici, C.P.; Szakacs, A.R.; Catinean, A.; et al. Natural Endotoxemia in Dogs—A Hidden Condition That Can Be Treated with a Potential Probiotic Containing Bacillus Subtilis, Bacillus Licheniformis and Pediococcus Acidilactici: A Study Model. Animals 2021, 11, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littman, M.P.; Dambach, D.M.; Vaden, S.L.; Giger, U. Familial Protein-Losing Enteropathy and Protein-Losing Nephropathy in Soft Coated Wheaten Terriers: 222 Cases (1983–1997). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2000, 14, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, M.; Steiner, J.M.; Fosgate, G.T.; Zentek, J.; Hartmann, S.; Kohn, B. Chronic Diarrhea in Dogs—Retrospective Study in 136 Cases. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerquetella, M.; Spaterna, A.; Laus, F.; Tesei, B.; Rossi, G.; Antonelli, E.; Villanacci, V.; Bassotti, G. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Dog: Differences and Similarities with Humans. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohs, S.J. Safety and Efficacy of Shilajit (Mumie, Moomiyo). Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, B.A.G.; Motta, F.L.; Santana, M.H.A. Humic Acids: Structural Properties and Multiple Functionalities for Novel Technological Developments. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 62, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.H. Humic Matter in Soil and the Environment: Principles and Controversies, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Swidsinski, A.; Dörffel, Y.; Loening-Baucke, V.; Gille, C.; Reißhauer, A.; Göktas, O.; Krüger, M.; Neuhaus, J.; Schrödl, W. Impact of Humic Acids on the Colonic Microbiome in Healthy Volunteers. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xu, P.; Shao, M.; Wei, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Humic Acids Alleviate Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis by Positively Modulating Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1147110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Wei, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, J. Sodium Humate Alters the Intestinal Microbiome, Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Eggshell Ultrastructure, and Egg Performance of Old Laying Hens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 986562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, K.; Deng, S.; Liu, Y. Sodium Humate Alleviates LPS-Induced Intestinal Barrier Injury by Improving Intestinal Immune Function and Regulating Gut Microbiota. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 161, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junek, R.; Morrow, R.; Schoenherr, J.I.; Schubert, R.; Kallmeyer, R.; Phull, S.; Klöcking, R. Bimodal Effect of Humic Acids on the LPS-Induced TNF-Alpha Release from Differentiated U937 Cells. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zheng, C.; Li, W. Alchemizing Earth’s Legacy: Bismuth-Engineered Humic Nanoparticles for IBD Theranostics through Mitochondrial Anti-Inflammation and Sustained Intestinal Delivery. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 33, 101948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, D.; Palkovicsné Pézsa, N.; Jerzsele, Á.; Süth, M.; Farkas, O. Protective Effects of Grape Seed Oligomeric Proanthocyanidins in IPEC-J2–Escherichia Coli/Salmonella Typhimurium Co-Culture. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palócz, O.; Pászti-Gere, E.; Gálfi, P.; Farkas, O. Chlorogenic Acid Combined with Lactobacillus Plantarum 2142 Reduced LPS-Induced Intestinal Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in IPEC-J2 Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Liu, X.; Dai, R.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Bi, D.; Shi, D. Enterococcus Faecium HDRsEf1 Protects the Intestinal Epithelium and Attenuates ETEC-Induced IL-8 Secretion in Enterocytes. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 7474306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, A.; Gonzalez, L.; Blikslager, A. Large Animal Models: The Key to Translational Discovery in Digestive Disease Research. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 2, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiveland, C.R. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. In The Impact of Food Bioactives on Health: In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models; Verhoeckx, K., Cotter, P., López-Expósito, I., Kleiveland, C., Lea, T., Mackie, A., Requena, T., Swiatecka, D., Wichers, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vašková, J.; Veliká, B.; Pilátová, M.; Kron, I.; Vaško, L. Effects of Humic Acids in Vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2011, 47, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalvon-Demersay, T.; Luise, D.; Le Floc’h, N.; Tesseraud, S.; Lambert, W.; Bosi, P.; Trevisi, P.; Beaumont, M.; Corrent, E. Functional Amino Acids in Pigs and Chickens: Implication for Gut Health. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 663727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierack, P.; Nordhoff, M.; Pollmann, M.; Weyrauch, K.D.; Amasheh, S.; Lodemann, U.; Jores, J.; Tachu, B.; Kleta, S.; Blikslager, A.; et al. Characterization of a Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cell Line for in Vitro Studies of Microbial Pathogenesis in Swine. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2006, 125, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Nuro-Gyina, P.K.; Islam, M.A.; Tesfaye, D.; Tholen, E.; Looft, C.; Schellander, K.; Cinar, M.U. Expression Dynamics of Toll-like Receptors mRNA and Cytokines in Porcine Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Stimulated by Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2012, 147, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Bruns, A.H.; Donnelly, H.K.; Wunderink, R.G. Comparative in Vitro Stimulation with Lipopolysaccharide to Study TNFalpha Gene Expression in Fresh Whole Blood, Fresh and Frozen Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. J. Immunol. Methods 2010, 357, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karancsi, Z.; Móritz, A.V.; Lewin, N.; Veres, A.M.; Jerzsele, Á.; Farkas, O. Beneficial Effect of a Fermented Wheat Germ Extract in Intestinal Epithelial Cells in Case of Lipopolysaccharide-Evoked Inflammation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1482482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruslanov, E.; Kusmartsev, S. Identification of ROS Using Oxidized DCFDA and Flow-Cytometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 594, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luise, D.; Bosi, P.; Raff, L.; Amatucci, L.; Virdis, S.; Trevisi, P. Bacillus Spp. Probiotic Strains as a Potential Tool for Limiting the Use of Antibiotics, and Improving the Growth and Health of Pigs and Chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 801827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhernov, Y.V.; Kremb, S.; Helfer, M.; Schindler, M.; Harir, M.; Mueller, C.; Hertkorn, N.; Avvakumova, N.P.; Konstantinov, A.I.; Brack-Werner, R.; et al. Supramolecular Combinations of Humic Polyanions as Potent Microbicides with Polymodal Anti-HIV-Activities. New J. Chem. 2016, 41, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palócz, O.; Szita, G.; Csikó, G. Alteration in Inflammatory Responses and Cytochrome P450 Expression of Porcine Jejunal Cells by Drinking Water Supplements. Mediat. Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 5420381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honneffer, J.B.; Minamoto, Y.; Suchodolski, J.S. Microbiota Alterations in Acute and Chronic Gastrointestinal Inflammation of Cats and Dogs. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 16489–16497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Al-Sadi, R.; Said, H.M.; Ma, T.Y. Lipopolysaccharide Causes an Increase in Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability in Vitro and in Vivo by Inducing Enterocyte Membrane Expression and Localization of TLR-4 and CD14. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezierski, A.; Czechowski, F.; Jerzykiewicz, M.; Chen, Y.; Drozd, J. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Studies on Stable and Transient Radicals in Humic Acids from Compost, Soil, Peat and Brown Coal. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2000, 56A, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-L.; Ho, H.-Y.; Huang, Y.-W.; Lu, F.-J.; Chiu, D.T.-Y. Humic Acid Induces Oxidative DNA Damage, Growth Retardation, and Apoptosis in Human Primary Fibroblasts. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003, 228, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, U.D.; Marković, M.M.; Cupać, S.B.; Tomić, Z.P. Soil Humic Acid Aggregation by Dynamic Light Scattering and Laser Doppler Electrophoresis. J. Plant Nutr. Soil. Sci. 2013, 176, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, J.F.L.; Wilkinson, K.J.; van Leeuwen, H.P.; Buffle, J. Humic Substances Are Soft and Permeable: Evidence from Their Electrophoretic Mobilities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 6435–6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.; Thiemermann, C. Role of Metabolic Endotoxemia in Systemic Inflammation and Potential Interventions. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 594150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gau, R.J.; Yang, H.L.; Chow, S.N.; Suen, J.L.; Lu, F.J. Humic Acid Suppresses the LPS-Induced Expression of Cell-Surface Adhesion Proteins through the Inhibition of NF-kappaB Activation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2000, 166, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rensburg, C.E.J. The Antiinflammatory Properties of Humic Substances: A Mini Review. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Liu, K.; He, Y.; Deng, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D. Sodium Humate Ameliorates LPS-Induced Liver Injury in Mice by Inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB and Activating NRF2/HO-1 Signaling Pathways. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.E.; van Sambeek, D.M.; Gabler, N.K.; Kerr, B.J.; Moreland, S.; Johal, S.; Edmonds, M.S. Effects of Dietary Humic and Butyric Acid on Growth Performance and Response to Lipopolysaccharide in Young Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 4172–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jergens, A.E.; Heilmann, R.M. Canine Chronic Enteropathy—Current State-of-the-Art and Emerging Concepts. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 923013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Móritz, A.V.; Farkas, O.; Jerzsele, Á.; Palkovicsné Pézsa, N. Protective Effects of Humic Acid on Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Inflammatory Activation in Canine Cell-Based Models. Animals 2026, 16, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020173

Móritz AV, Farkas O, Jerzsele Á, Palkovicsné Pézsa N. Protective Effects of Humic Acid on Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Inflammatory Activation in Canine Cell-Based Models. Animals. 2026; 16(2):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020173

Chicago/Turabian StyleMóritz, Alma Virág, Orsolya Farkas, Ákos Jerzsele, and Nikolett Palkovicsné Pézsa. 2026. "Protective Effects of Humic Acid on Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Inflammatory Activation in Canine Cell-Based Models" Animals 16, no. 2: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020173

APA StyleMóritz, A. V., Farkas, O., Jerzsele, Á., & Palkovicsné Pézsa, N. (2026). Protective Effects of Humic Acid on Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Inflammatory Activation in Canine Cell-Based Models. Animals, 16(2), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020173