Genome-Wide Characterization of Four Gastropod Species Ionotropic Receptors Reveals Diet-Linked Evolutionary Patterns of Functional Divergence

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Availability and Sample Collection

2.2. Identification, Chromosomal Localization, and Collinearity Analysis of iGluR and IR Genes

2.3. Physicochemical Property and Subcellular Localization Analyses of IR Gene Family

2.4. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Construction of the IR Gene Family

2.5. Characterization of IR Gene Family: Motif, Gene Structure, and Domain Prediction Analyses

2.6. Selection Pressure Analysis of the IR Gene Family

2.7. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Analysis of the IR Gene Family

2.8. Transcriptome Analysis

2.9. RT-qPCR

3. Results

3.1. Identification, Classification, and Chromosomal Distribution of IR Gene Families in Four Gastropod Species

3.2. Physicochemical Properties and Subcellular Localization of the IR Gene Family

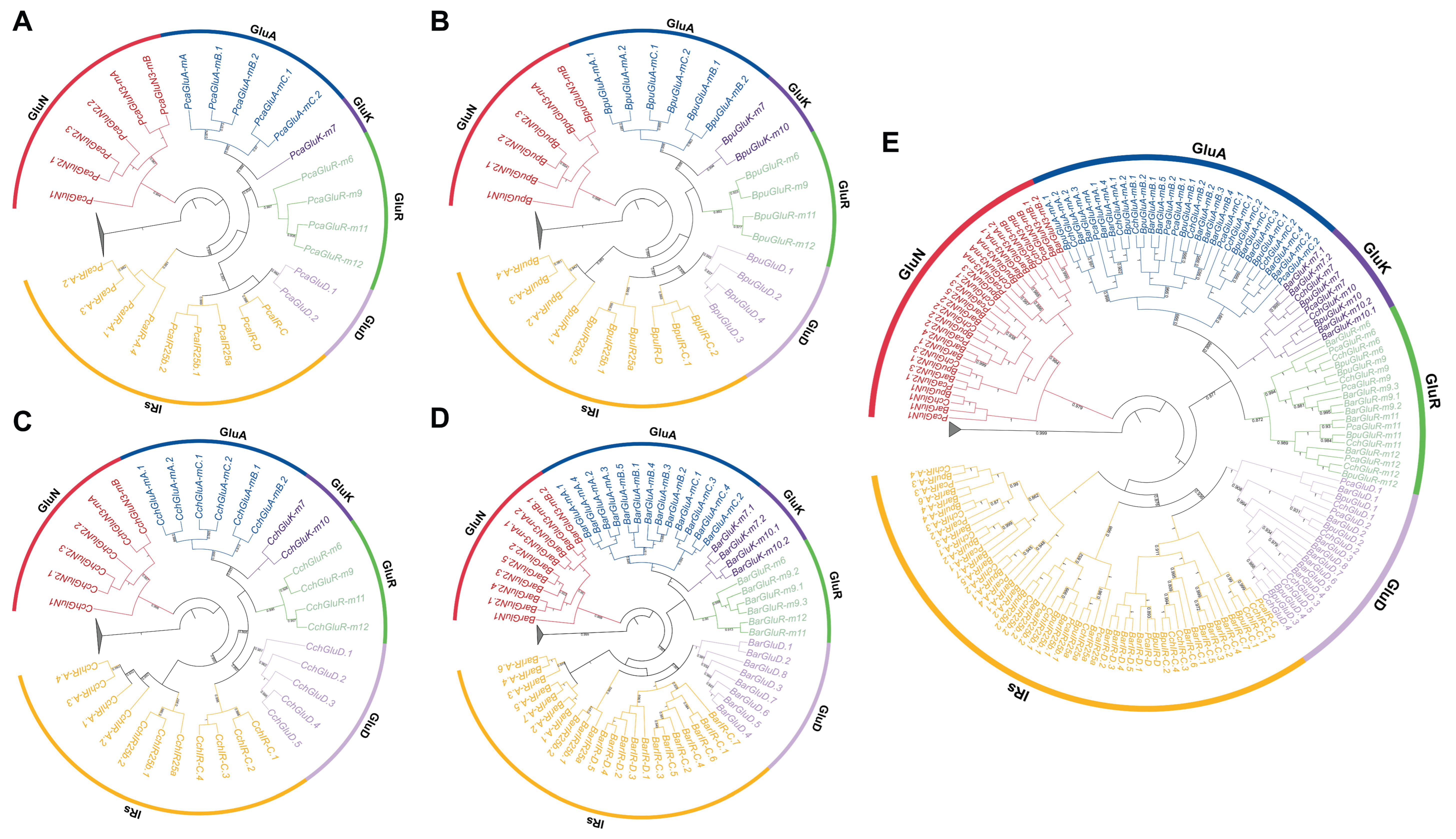

3.3. Phylogenetic Analyses of the IR Gene Family at Both Interspecific and Intraspecific Levels

3.4. Motif, Gene Structure, and Domain Prediction of the IR Gene Family

3.5. Selection Pressure Analysis of IR Genes

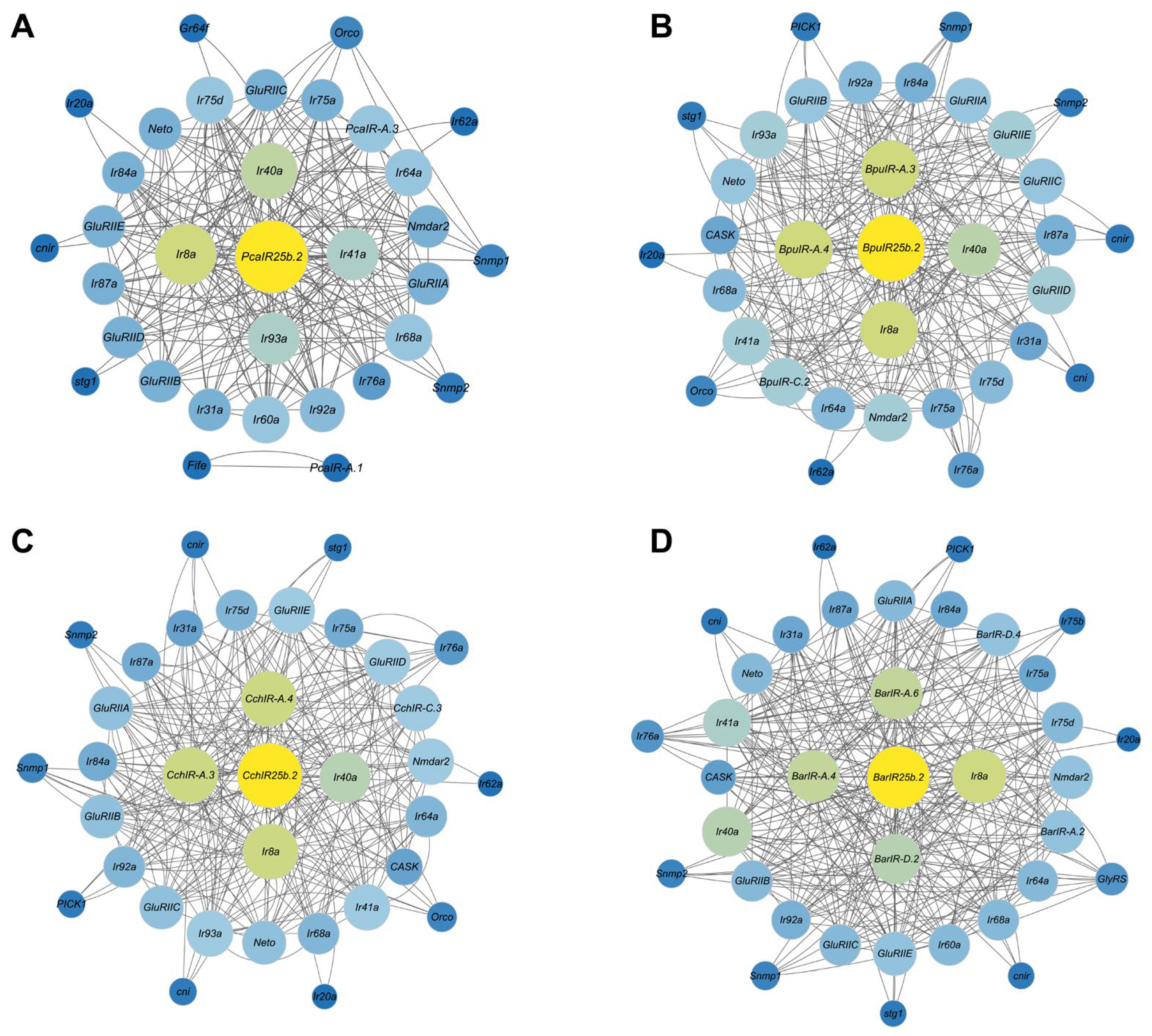

3.6. PPI Analysis of the IR Gene Family

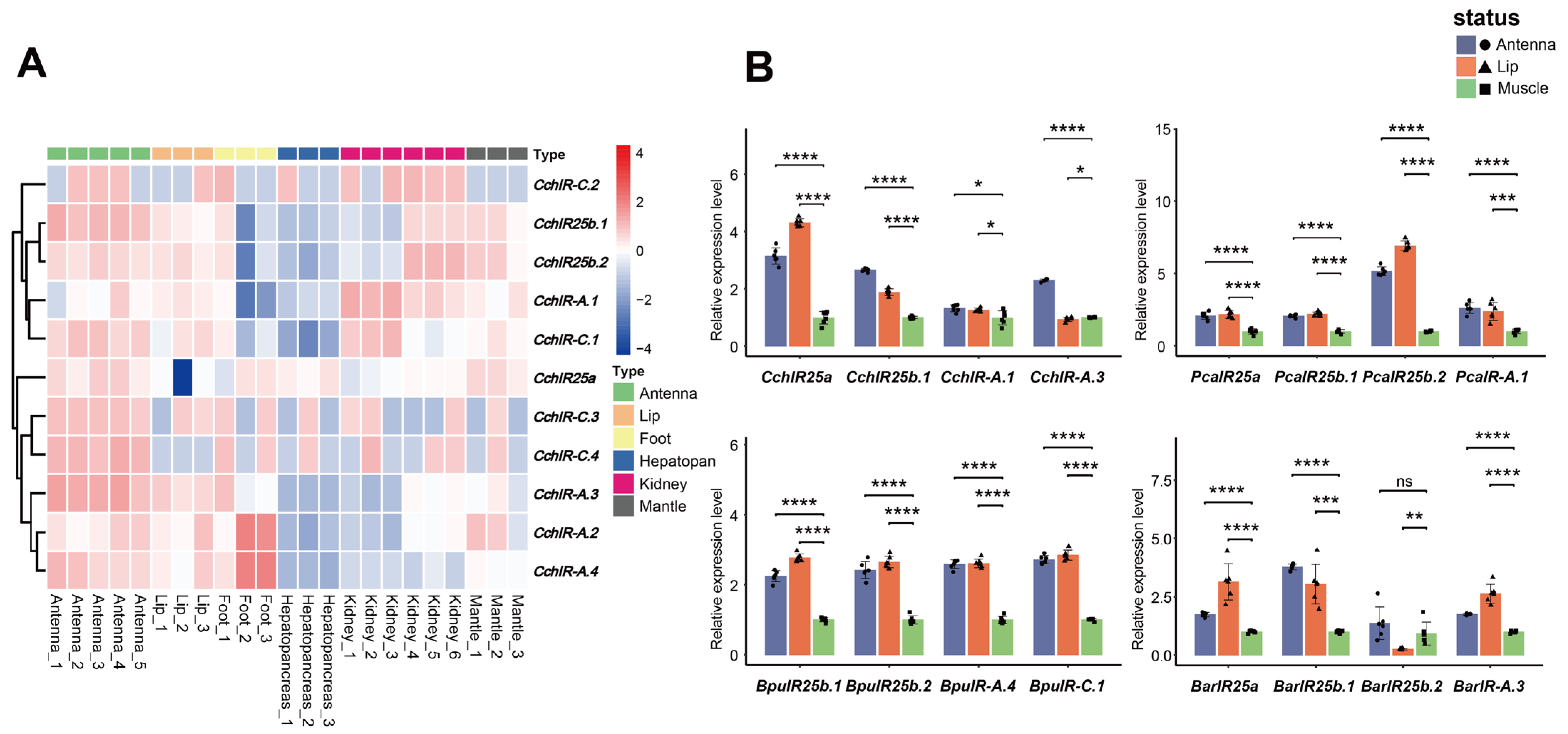

3.7. Tissue-Specific Expression Levels of CchIR Genes

3.8. Comparative Expression Levels of IR Genes Across Four Gastropod Species

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamio, M.; Yambe, H.; Fusetani, N. Chemical cues for intraspecific chemical communication and interspecific interactions in aquatic environments: Applications for fisheries and aquaculture. Fish. Sci. 2022, 88, 203–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohe, L.R.; Brand, P. Evolutionary ecology of chemosensation and its role in sensory drive. Curr. Zool. 2018, 64, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.-L.; Yang, M.-J.; Song, H.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, X.-T. Gastropod chemoreception behaviors—Mechanisms underlying the perception and location of targets and implications for shellfish fishery development in aquatic environments. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1042962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.C. Sensory ecology of predator-induced phenotypic plasticity. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollo, E.; Boero, F.; Peñuelas, J.; Fontana, A.; Garson, M.J.; Roussis, V.; Cerrano, C.; Polese, G.; Cattaneo, A.M.; Mudianta, I.W.; et al. Taste and smell: A unifying chemosensory theory. Q. Rev. Biol. 2022, 97, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-Y.; Menuz, K.; Carlson, J.R. Olfactory perception: Receptors, cells, and circuits. Cell 2009, 139, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhara, K.; Vosshall, L.B. Sensing odorants and pheromones with chemosensory receptors. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009, 71, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, R.; Vannice, K.S.; Gomez-Diaz, C.; Vosshall, L.B. Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila. Cell 2009, 136, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croset, V.; Rytz, R.; Cummins, S.F.; Budd, A.; Brawand, D.; Kaessmann, H.; Gibson, T.J.; Benton, R. Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twomey, E.C.; Sobolevsky, A.I. Structural mechanisms of gating in ionotropic glutamate receptors. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, E.; Regan, M.C.; Furukawa, H. Emerging structural insights into the function of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traynelis, S.F.; Wollmuth, L.P.; McBain, C.J.; Menniti, F.S.; Vance, K.M.; Ogden, K.K.; Hansen, K.B.; Yuan, H.; Myers, S.J.; Dingledine, R. Glutamate receptor ion channels: Structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 405–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, L. The structure and function of ionotropic receptors in Drosophila. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 638839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuin, L.; Prieto-Godino, L.L.; Pan, H.; Gutierrez, C.; Huang, L.; Jin, R.; Benton, R. In vivo assembly and trafficking of olfactory ionotropic receptors. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytz, R.; Croset, V.; Benton, R. Ionotropic receptors (IRs): Chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors in Drosophila and beyond. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 43, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.L. Glutamate receptors at atomic resolution. Nature 2006, 440, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Wang, T.; Rotgans, B.A.; McManus, D.P.; Cummins, S.F. Ionotropic Receptors identified within the tentacle of the freshwater snail Biomphalaria glabrata, an Intermediate Host of Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Giesen, L.; Garrity, P.A. More than meets the IR: The expanding roles of variant ionotropic glutamate receptors in sensing odor, taste, temperature and moisture. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, J.; Pregitzer, P.; Breer, H.; Krieger, J. Access to the odor world: Olfactory receptors and their role for signal transduction in insects. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2018, 75, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelchenko, A.A.; Bai, H.; Spina, E.C.; Tyrrell, J.J.; Wilbourne, J.T.; Ni, L. Cool and warm ionotropic receptors control multiple thermotaxes in Drosophila larvae. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1023492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M.; Blais, S.; Park, J.-Y.; Min, S.; Neubert, T.A.; Suh, G.S.B. Ionotropic glutamate receptors IR64a and IR8a form a functional odorant receptor complex in vivo in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 10741–10749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enjin, A.; Zaharieva, E.E.; Frank, D.D.; Mansourian, S.; Suh, G.S.B.; Gallio, M.; Stensmyr, M.C. Humidity sensing in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Zhang, M.; Üçpunar, H.K.; Svensson, T.; Quillery, E.; Gompel, N.; Ignell, R.; Kadow, I.C.G. Ionotropic chemosensory receptors mediate the taste and smell of polyamines. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, Z.A.; Silbering, A.F.; Ni, L.; Klein, M.; Budelli, G.; Bell, R.; Abuin, L.; Ferrer, A.J.; Samuel, A.D.; Benton, R.; et al. Distinct combinations of variant ionotropic glutamate receptors mediate thermosensation and hygrosensation in Drosophila. eLife 2016, 5, e17879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, T.-W.; He, Z.; Gorur-Shandilya, S.; Menuz, K.; Larter, N.K.; Stewart, S.; Carlson, J.R. The Drosophila IR20a clade of ionotropic receptors are candidate taste and pheromone receptors. Neuron 2014, 83, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Klein, M.; Svec, K.V.; Budelli, G.; Chang, E.C.; Ferrer, A.J.; Benton, R.; Samuel, A.D.; Garrity, P.A. The ionotropic receptors IR21a and IR25a mediate cool sensing in Drosophila. eLife 2016, 5, e13254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Pang, L.; Duong, V.-K.; Lee, A.; Schoniger, H.; Varady, E.; Dahanukar, A. A molecular and cellular context-dependent role for Ir76b in detection of amino acid taste. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z. Characterization of ionotropic receptor gene EonuIR25a in the tea green leafhopper, Empoasca onukii matsuda. Plants 2023, 12, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, S.; Hu, S.; Wang, P.; Liu, T.; Fan, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H. Ionotropic receptor 8a (Ir8a) plays an important role in acetic acid perception in the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 24207–24218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.-Q.; Zhang, D.-D.; Powell, D.; Wang, H.-L.; Andersson, M.N.; Löfstedt, C. Ionotropic receptors in the turnip moth Agrotis segetum respond to repellent medium-chain fatty acids. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Wang, S.-N.; Song, X.; Khashaveh, A.; Lu, Z.-Y.; Dhiloo, K.H.; Li, R.-J.; Gao, X.-W.; Zhang, Y.-J. Antennal ionotropic receptors IR64a1 and IR64a2 of the parasitoid wasp Microplitis mediator (Hymenoptera: Braconidate) collaboratively perceive habitat and host cues. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 114, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Y. Taste coding of heavy metal ion-induced avoidance in Drosophila. Iscience 2023, 26, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audino, J.A.; McElroy, K.E.; Serb, J.M.; Marian, J.E.A.R. Anatomy and transcriptomics of the common Jingle shell (Bivalvia, Anomiidae) support a sensory function for bivalve tentacles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andouche, A.; Valera, S.; Baratte, S. Exploration of chemosensory ionotropic receptors in cephalopods: The IR25 gene is expressed in the olfactory organs, suckers, and fins of Sepia officinalis. Chem. Senses 2021, 46, bjab047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.F.; Wangensteen, O.S.; Renema, W.; Meyer, C.P.; Fontanilla, I.K.C.; Todd, J.A. Global species hotspots and COI barcoding cold spots of marine Gastropoda. Biodivers. Conserv. 2024, 33, 2925–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.B.; Fogel, N.S.; Lambert, J.D. Growth and morphogenesis of the gastropod shell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 6878–6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, E.E.; Gargominy, O.; Ponder, W.F.; Bouchet, P. Global diversity of gastropods (Gastropoda; Mollusca) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 2008, 595, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, D.G. Fine structure of olfactory epithelia of gastropod molluscs. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1992, 22, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyeth, R.C. Olfactory navigation in aquatic gastropods. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb185843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.J.H.; Susswein, A.J. Comparative neuroethology of feeding control in molluscs. J. Exp. Biol. 2002, 205, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29–W37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collingridge, G.L.; Olsen, R.W.; Peters, J.; Spedding, M. A nomenclature for ligand-gated ion channels. Neuropharmacology 2009, 56, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvaud, S.; Gabella, C.; Lisacek, F.; Stockinger, H.; Ioannidis, V.; Durinx, C. Expasy, the swiss bioinformatics resource portal, as designed by its users. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W216–W227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Vicente, D.; Ji, J.; Gratacòs-Batlle, E.; Gou, G.; Reig-Viader, R.; Luís, J.; Burguera, D.; Navas-Perez, E.; García-Fernández, J.; Fuentes-Prior, P.; et al. Metazoan evolution of glutamate receptors reveals unreported phylogenetic groups and divergent lineage-specific events. eLife 2018, 7, e35774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Bo, Y.; Han, L.; He, J.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D200–D203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geourjon, C.; Deléage, G. SOPMA: Significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus prediction from multiple alignments. Bioinformatics 1995, 11, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: A toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2010, 8, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Dai, L. ParaAT: A parallel tool for constructing multiple protein-coding DNA alignments. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 419, 779–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Sahni, S. String correction using the Damerau-Levenshtein distance. BMC Bioinform. 2019, 20, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otasek, D.; Morris, J.H.; Bouças, J.; Pico, A.R.; Demchak, B. Cytoscape automation: Empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, R.; Khan, A.; Alghamdi, B.S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Alghanmi, M.; Ahmad, A.; Bashir, S.S.; Haq, Q.M.R. An insight into animal glutamate receptors homolog of Arabidopsis thaliana and their potential applications—A review. Plants 2022, 11, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.B.; Jelesko, J.; Okumoto, S. Glutamate receptor homologs in plants: Functions and evolutionary origins. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, J.B.; Khuri, S.; Fieber, L.A. Phylogenetic analysis of ionotropic L-glutamate receptor genes in the Bilateria, with special notes on Aplysia californica. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Si, Y.; Wen, X.; Wang, L.; Song, L. Unveiling the functional diversity of ionotropic glutamate receptors in the pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) by systematic studies. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1280553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Ai, M.; Shin, S.A.; Suh, G.S.B. Dedicated olfactory neurons mediating attraction behavior to ammonia and amines in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E1321–E1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derby, C.D.; Sorensen, P.W. Neural processing, perception, and behavioral responses to natural chemical stimuli by fish and crustaceans. J. Chem. Ecol. 2008, 34, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuin, L.; Bargeton, B.; Ulbrich, M.H.; Isacoff, E.Y.; Kellenberger, S.; Benton, R. Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron 2011, 69, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, S.; Lee, Y. The multidimensional ionotropic receptors of Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol. Biol. 2018, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Pellegrino, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Vosshall, L.B.; Touhara, K. Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature 2008, 452, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchler, J.A.; Yang, H. The multiple fates of gene duplications: Deletion, hypofunctionalization, subfunctionalization, neofunctionalization, dosage balance constraints, and neutral variation. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 2466–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadum, S.; Banerjee, U.; Murugan, P.; Gangapur, D.; Ravikesavan, R. Gene duplication as a major force in evolution. J. Genet. 2013, 92, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Nie, Y.; Xu, T.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Shi, P.; Liu, F.; Zhao, H.; Ma, Q.; et al. Evolutionary process underlying receptor gene expansion and cellular divergence of olfactory sensory neurons in honeybees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2025, 42, msaf080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Rokas, A.; Berger, S.L.; Liebig, J.; Ray, A.; Zwiebel, L.J. Chemoreceptor evolution in hymenoptera and its implications for the evolution of eusociality. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 2407–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidel-Fischer, H.M.; Kirsch, R.; Reichelt, M.; Ahn, S.-J.; Wielsch, N.; Baxter, S.W.; Heckel, D.G.; Vogel, H.; Kroymann, J. An insect counteradaptation against host plant defenses evolved through concerted neofunctionalization. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Mu, H.; Ip, J.C.H.; Li, R.; Xu, T.; Accorsi, A.; Sánchez Alvarado, A.; Ross, E.; Lan, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Signatures of divergence, invasiveness, and terrestrialization revealed by four apple snail genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 1507–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaurain, M.; Salabert, A.-S.; Payoux, P.; Gras, E.; Talmont, F. NMDA receptors: Distribution, role, and insights into neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolevsky, A.I.; Rosconi, M.P.; Gouaux, E. X-ray structure, symmetry and mechanism of an AMPA-subtype glutamate receptor. Nature 2009, 462, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, G.G.; Grebe, L.J.; Schinkel, R.; Lieb, B. The evolution of hemocyanin genes in Caenogastropoda: Gene duplications and intron accumulation in highly diverse gastropods. J. Mol. Evol. 2021, 89, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Name | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| CchIR25a | CGCACAGCACATCTACAT | TTCCGCATCCATCACAAG |

| CchIR25b.1 | TGAACGATTACCAGAAGGAA | GAAGTGCCAGAGAACCAA |

| CchIR-A.1 | ACACAATCTCGCTCCAAG | GGTAATGAGTAGTCCACAATG |

| CchIR-A.3 | TTCTGTTGCTCTTCTTATGC | GATGTTCTTCGTCTTCCAAT |

| PcaIR25a | ATGGAGTCAGCAGTGGTA | CATCTACAGTCGTGAGGTTA |

| PcaIR25b.1 | GCGATGTCTGGAATGTCA | AACGAGGAAGGAAGGAATG |

| PcaIR25b.2 | GCAACTTACTCGTGACAAC | GCAGGCATTCCAACCATA |

| PcaIR-A.1 | CAGGAAGACAACACAACAC | TGAGACAGAGCACCAAGA |

| BpuIR25b.1 | CTGATGAAGAAGCCTGACA | CGAAGACGAAGAGCAAGA |

| BpuIR25b.2 | AGGACAGTTGTGCCAGTA | CGAAGCGGTAGTTGAAGT |

| BpuIR-A.4 | GGTCTTCTTGTGGAGTTAGT | CTGTATGCTGGTTGTCTGA |

| BpuIR-C.1 | TTCTCGTCACCATTCATCTT | CCGTTACCACAGCAATCA |

| BarIR25a | TCATCATCGCCACCTACA | CTTCATCGTCTGCCACAA |

| BarIR25b.1 | GCACAGAGAAGGAGGATG | TGATGACCACCGAGAAGA |

| BarIR25b.2 | TGGAAGAACATCAGCAACA | GAAGAGCGAAGGCATAGG |

| BarIR-A.3 | TTCTGATTGGACGGTTCTC | AGGTGTAGGCGATGATGA |

| Cchβ-actin | CTGGAAGGTGGACAGAGAGG | AAATCATCGCTCCACCAGAG |

| Pcaβ-actin | TCACCATTGGCAACGAGCGAT | TCTCGTGAATACCAGCCGACT |

| Bpuβ-actin | CAAGCGTGGTATCCTGAC | TGGAGCCTCTGTAAGAAGTA |

| Barβ-actin | GGTTCACCATCCCTCAAGTACCC | GGGTCATCTTTTCACGGTTGG |

| Gene Name | Amino Acid Length (aa) | Molecular Weights (kDa) | Isoelectric Point (pI) | Instability Index | Aliphatic Index | Grand Average of Hydropathicity (GRAVY) | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PcaIR25a | 876 | 98.59 | 5.21 | 41 | 90.34 | −0.15 | Plasma membrane |

| PcaIR25b.1 | 949 | 105.94 | 5.9 | 42.53 | 100 | 0.063 | Plasma membrane |

| PcaIR25b.2 | 839 | 92.98 | 4.9 | 32.37 | 93.89 | 0.084 | Plasma membrane |

| PcaIR-A.1 | 499 | 55.56 | 5.9 | 43.22 | 91.86 | 0.142 | Plasma membrane |

| PcaIR-A.2 | 540 | 59.61 | 5.16 | 43.93 | 88 | −0.286 | Plasma membrane |

| PcaIR-A.3 | 436 | 49.60 | 8.82 | 39.16 | 99.31 | 0.056 | Plasma membrane |

| PcaIR-A.4 | 462 | 52.31 | 5.92 | 40.96 | 89.44 | −0.068 | Plasma membrane |

| PcaIR-C | 655 | 74.40 | 6.77 | 40.36 | 88.38 | 0.004 | Plasma membrane |

| PcaIR-D | 855 | 96.73 | 4.7 | 49.34 | 91.54 | −0.143 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR25a | 847 | 95.51 | 5.07 | 43.93 | 100.65 | 0.001 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR25b.1 | 891 | 100.07 | 5.48 | 38.62 | 89.57 | −0.054 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR25b.2 | 827 | 92.27 | 5.14 | 33.45 | 91.93 | 0.099 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR-A.1 | 497 | 56.05 | 8.07 | 45.96 | 92.39 | −0.002 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR-A.2 | 505 | 56.63 | 6.91 | 43.83 | 100.73 | 0.132 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR-A.3 | 484 | 54.09 | 8.83 | 28.98 | 93.9 | −0.055 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR-A.4 | 533 | 59.51 | 5.17 | 49.67 | 83.3 | −0.285 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR-C.1 | 595 | 66.73 | 6.25 | 54.39 | 95.13 | 0.18 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR-C.2 | 454 | 51.43 | 7.53 | 37.96 | 96.81 | −0.031 | Plasma membrane |

| BpuIR-D | 729 | 81.48 | 4.7 | 37.18 | 96.65 | 0.072 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR25a | 914 | 102.66 | 5.15 | 42.08 | 100.57 | −0.005 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR25b.1 | 883 | 99.17 | 5.54 | 37.33 | 89.72 | −0.048 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR25b.2 | 1013 | 113.76 | 5.53 | 36.18 | 88.08 | −0.086 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR-A.1 | 502 | 56.20 | 5.61 | 46.34 | 98.43 | 0.089 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR-A.2 | 518 | 58.43 | 6.06 | 44.46 | 87.7 | −0.105 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR-A.3 | 533 | 59.51 | 5.17 | 49.61 | 82.93 | −0.282 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR-A.4 | 484 | 54.15 | 8.83 | 28.82 | 94.5 | −0.058 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR-C.1 | 582 | 65.04 | 6.58 | 53.47 | 93.04 | 0.172 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR-C.2 | 633 | 72.13 | 8 | 41.19 | 90.03 | −0.008 | Plasma membrane |

| CchIR-C.3 | 696 | 79.07 | 8.56 | 39.07 | 91.15 | −0.087 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| CchIR-C.4 | 650 | 74.21 | 7.53 | 36.75 | 98.91 | 0.047 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR25a | 1001 | 112.56 | 5.02 | 43.21 | 86.45 | −0.118 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR25b.1 | 831 | 92.99 | 4.92 | 42.02 | 84.19 | −0.116 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR25b.2 | 733 | 81.34 | 5.62 | 47.55 | 87.24 | −0.004 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-A.1 | 497 | 55.50 | 7.18 | 31.05 | 90.76 | 0.034 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| BarIR-A.2 | 472 | 52.63 | 5.53 | 37.92 | 95.34 | 0.072 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-A.3 | 505 | 55.66 | 5.46 | 39.39 | 90.02 | −0.182 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-A.4 | 477 | 52.22 | 8.8 | 35.61 | 90.29 | 0.034 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-A.5 | 496 | 55.28 | 6.18 | 41.15 | 88.87 | 0.042 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-A.6 | 503 | 55.41 | 6.44 | 32.87 | 90.02 | 0.028 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-A.7 | 510 | 56.60 | 6.56 | 45.74 | 91.59 | 0.127 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-C.1 | 794 | 88.86 | 7.86 | 44.94 | 81.1 | −0.292 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-C.2 | 548 | 61.04 | 5.71 | 38.52 | 91.9 | −0.005 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-C.3 | 1239 | 138.13 | 6.3 | 35.45 | 94.51 | 0.087 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-C.4 | 453 | 49.23 | 6.41 | 37.69 | 99.87 | 0.242 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-C.5 | 599 | 66.99 | 7.59 | 28.37 | 94.16 | 0.086 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| BarIR-C.6 | 631 | 68.65 | 5.1 | 53.86 | 99.1 | 0.128 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-C.7 | 679 | 74.69 | 6.61 | 37.72 | 100.75 | 0.15 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| BarIR-D.1 | 903 | 100.33 | 5.56 | 38.88 | 80.71 | −0.322 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-D.2 | 1361 | 152.26 | 5.63 | 40.24 | 83.5 | −0.229 | Plasma membrane |

| BarIR-D.3 | 1134 | 127.98 | 8.08 | 55.78 | 81.29 | −0.351 | Plasma membrane |

| Gene ID | Alpha Helix/% | Extended Strand/% | Beta Turn/% | Random Coil/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PcaIR25a | 42.92% | 15.18% | 3.20% | 38.70% |

| PcaIR25b.1 | 45.63% | 14.86% | 3.16% | 36.35% |

| PcaIR25b.2 | 46.84% | 13.11% | 3.58% | 36.47% |

| PcaIR-A.1 | 41.68% | 15.23% | 3.61% | 39.48% |

| PcaIR-A.2 | 41.30% | 12.78% | 3.70% | 42.22% |

| PcaIR-A.3 | 43.35% | 16.51% | 4.13% | 36.01% |

| PcaIR-A.4 | 46.54% | 13.20% | 3.90% | 36.36% |

| PcaIR-C | 43.66% | 17.25% | 2.14% | 36.95% |

| PcaIR-D | 42.92% | 14.39% | 3.16% | 39.53% |

| CchIR25a | 39.18% | 16.31% | 4.08% | 40.43% |

| CchIR25b.1 | 42.13% | 12.67% | 2.11% | 43.09% |

| CchIR25b.2 | 43.37% | 14.16% | 2.60% | 39.86% |

| CchIR-A.1 | 44.55% | 15.96% | 3.32% | 36.18% |

| CchIR-A.2 | 44.50% | 18.56% | 3.95% | 32.99% |

| CchIR-A.3 | 33.42% | 11.17% | 2.53% | 52.88% |

| CchIR-A.4 | 34.23% | 8.96% | 2.69% | 54.12% |

| CchIR-C.1 | 42.82% | 17.53% | 3.16% | 36.49% |

| CchIR-C.2 | 40.92% | 14.66% | 2.63% | 41.79% |

| CchIR-C.3 | 44.46% | 17.38% | 3.23% | 34.92% |

| CchIR-C.4 | 43.73% | 15.89% | 3.75% | 36.62% |

| BpuIR25a | 41.32% | 15.70% | 3.07% | 39.91% |

| BpuIR25b.1 | 41.19% | 14.14% | 3.25% | 41.41% |

| BpuIR25b.2 | 42.44% | 17.17% | 3.14% | 37.24% |

| BpuIR-A.1 | 41.05% | 14.29% | 4.63% | 40.04% |

| BpuIR-A.2 | 41.98% | 15.64% | 4.16% | 38.22% |

| BpuIR-A.3 | 41.18% | 12.81% | 3.93% | 40.08% |

| BpuIR-A.4 | 37.52% | 13.13% | 3.56% | 45.78% |

| BpuIR-C.1 | 42.86% | 17.82% | 3.19% | 36.13% |

| BpuIR-C.2 | 48.24% | 16.74% | 4.41% | 30.62% |

| BpuIR-D | 44.99% | 13.85% | 3.57% | 37.59% |

| BarIR25a | 37.16% | 15.18% | 2.90% | 44.76% |

| BarIR25b.1 | 44.77% | 14.56% | 2.77% | 37.91% |

| BarIR25b.2 | 47.20% | 13.23% | 3.14% | 36.43% |

| BarIR-A.1 | 43.43% | 17.52% | 4.56% | 34.49% |

| BarIR-A.2 | 43.01% | 13.14% | 4.87% | 38.98% |

| BarIR-A.3 | 45.94% | 11.29% | 3.96% | 38.81% |

| BarIR-A.4 | 40.46% | 14.47% | 3.56% | 41.51% |

| BarIR-A.5 | 40.52% | 15.12% | 3.83% | 40.52% |

| BarIR-A.6 | 41.75% | 13.32% | 4.17% | 40.76% |

| BarIR-A.7 | 41.37% | 14.12% | 3.73% | 40.78% |

| BarIR-C.1 | 44.71% | 12.97% | 2.27% | 40.05% |

| BarIR-C.2 | 43.66% | 13.48% | 4.23% | 38.63% |

| BarIR-C.3 | 44.63% | 16.14% | 2.99% | 36.24% |

| BarIR-C.4 | 41.72% | 15.89% | 3.97% | 38.41% |

| BarIR-C.5 | 40.90% | 16.53% | 3.51% | 39.07% |

| BarIR-C.6 | 42.31% | 16.32% | 3.17% | 38.19% |

| BarIR-C.7 | 48.60% | 14.58% | 3.39% | 33.43% |

| BarIR-D.1 | 37.10% | 15.17% | 3.99% | 43.74% |

| BarIR-D.2 | 39.16% | 14.11% | 3.01% | 43.72% |

| BarIR-D.3 | 41.27% | 15.08% | 3.62% | 40.04% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, G.; Sun, Y.-Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Sun, N.-Y.; Wei, M.-J.; Shen, Y.-T.; Li, Y.-J.; Sun, Q.-Q.; Fujaya, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Characterization of Four Gastropod Species Ionotropic Receptors Reveals Diet-Linked Evolutionary Patterns of Functional Divergence. Animals 2026, 16, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020172

Wang G, Sun Y-Q, Wang F, Wang Z-Y, Sun N-Y, Wei M-J, Shen Y-T, Li Y-J, Sun Q-Q, Fujaya Y, et al. Genome-Wide Characterization of Four Gastropod Species Ionotropic Receptors Reveals Diet-Linked Evolutionary Patterns of Functional Divergence. Animals. 2026; 16(2):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020172

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Gang, Yi-Qi Sun, Fang Wang, Zhi-Yong Wang, Ni-Ying Sun, Meng-Jun Wei, Yu-Tong Shen, Yi-Jia Li, Quan-Qing Sun, Yushinta Fujaya, and et al. 2026. "Genome-Wide Characterization of Four Gastropod Species Ionotropic Receptors Reveals Diet-Linked Evolutionary Patterns of Functional Divergence" Animals 16, no. 2: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020172

APA StyleWang, G., Sun, Y.-Q., Wang, F., Wang, Z.-Y., Sun, N.-Y., Wei, M.-J., Shen, Y.-T., Li, Y.-J., Sun, Q.-Q., Fujaya, Y., Bian, X.-G., Yang, W.-Q., & Tan, K. (2026). Genome-Wide Characterization of Four Gastropod Species Ionotropic Receptors Reveals Diet-Linked Evolutionary Patterns of Functional Divergence. Animals, 16(2), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020172