Performance Evaluation of Fan-Ventilated Swine Trailer with Air Filtration for Maintaining Satisfactory Transport Conditions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Prototype Trailer

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Temperature Level Distribution

3.1.1. Temperature Time Series for the Entire Transport

3.1.2. Temperature During the Stable Transport Period

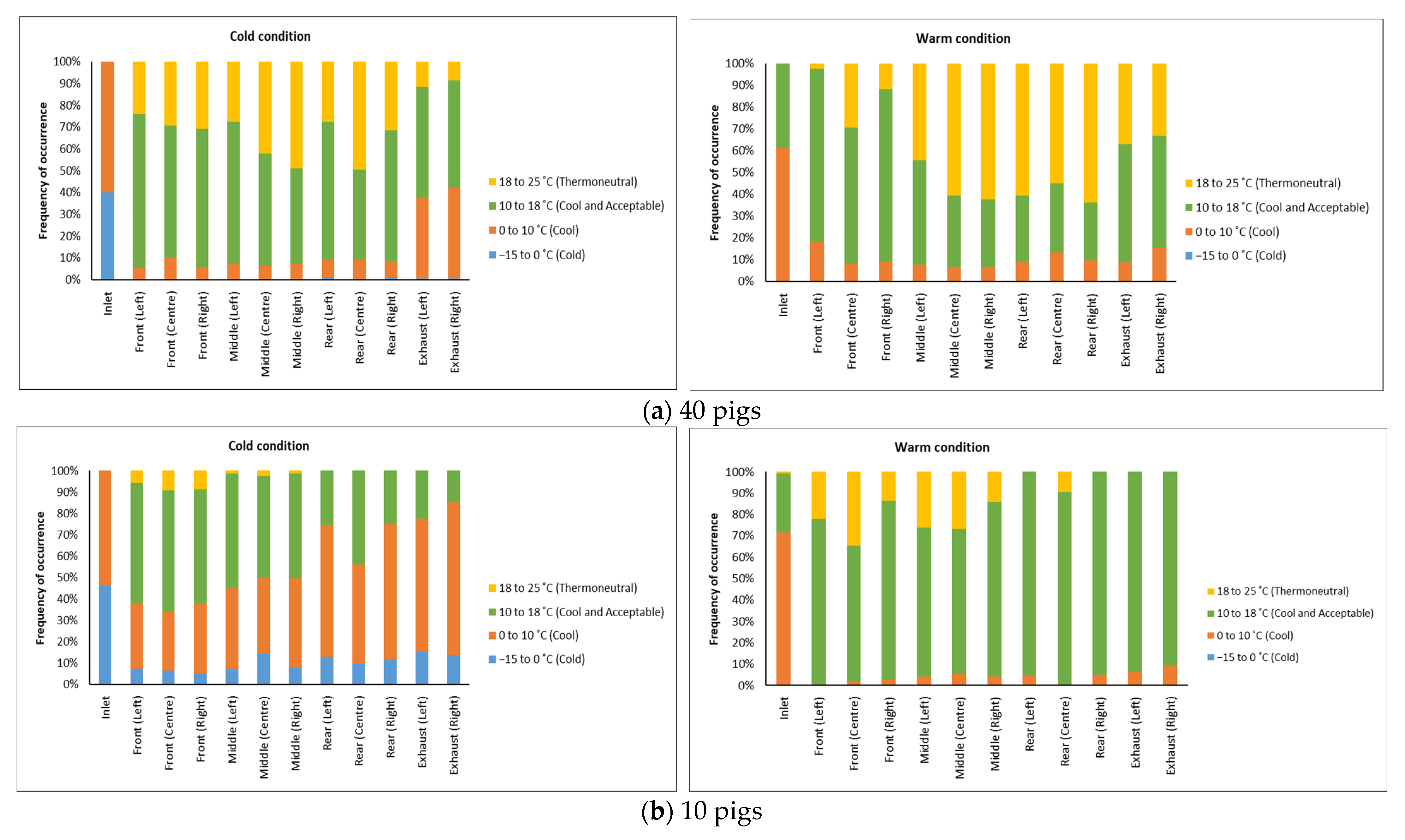

3.1.3. Thermal Comfort Classification

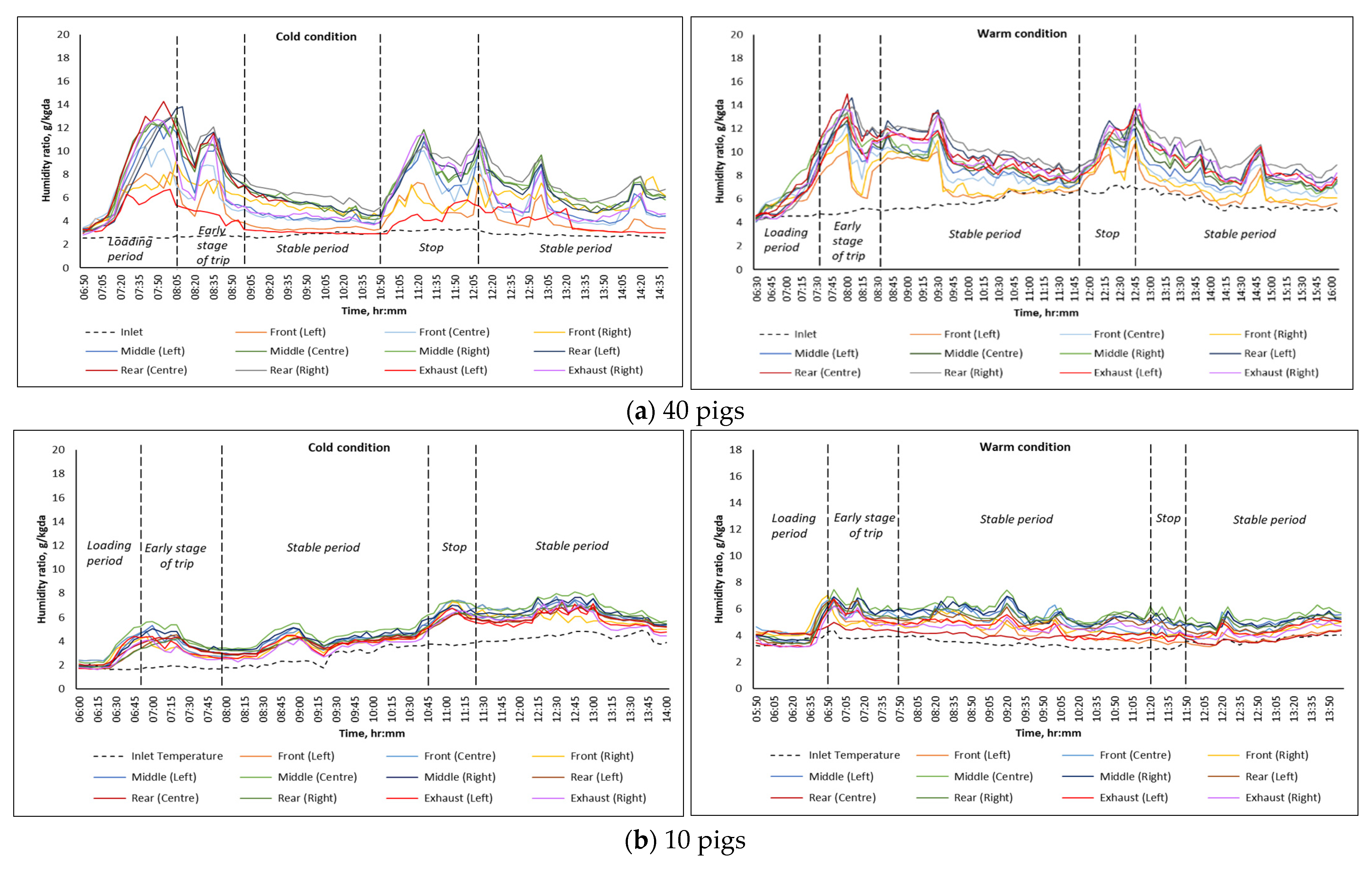

3.2. Moisture Levels and Distribution

3.2.1. Humidity Ratio for the Entire Transport

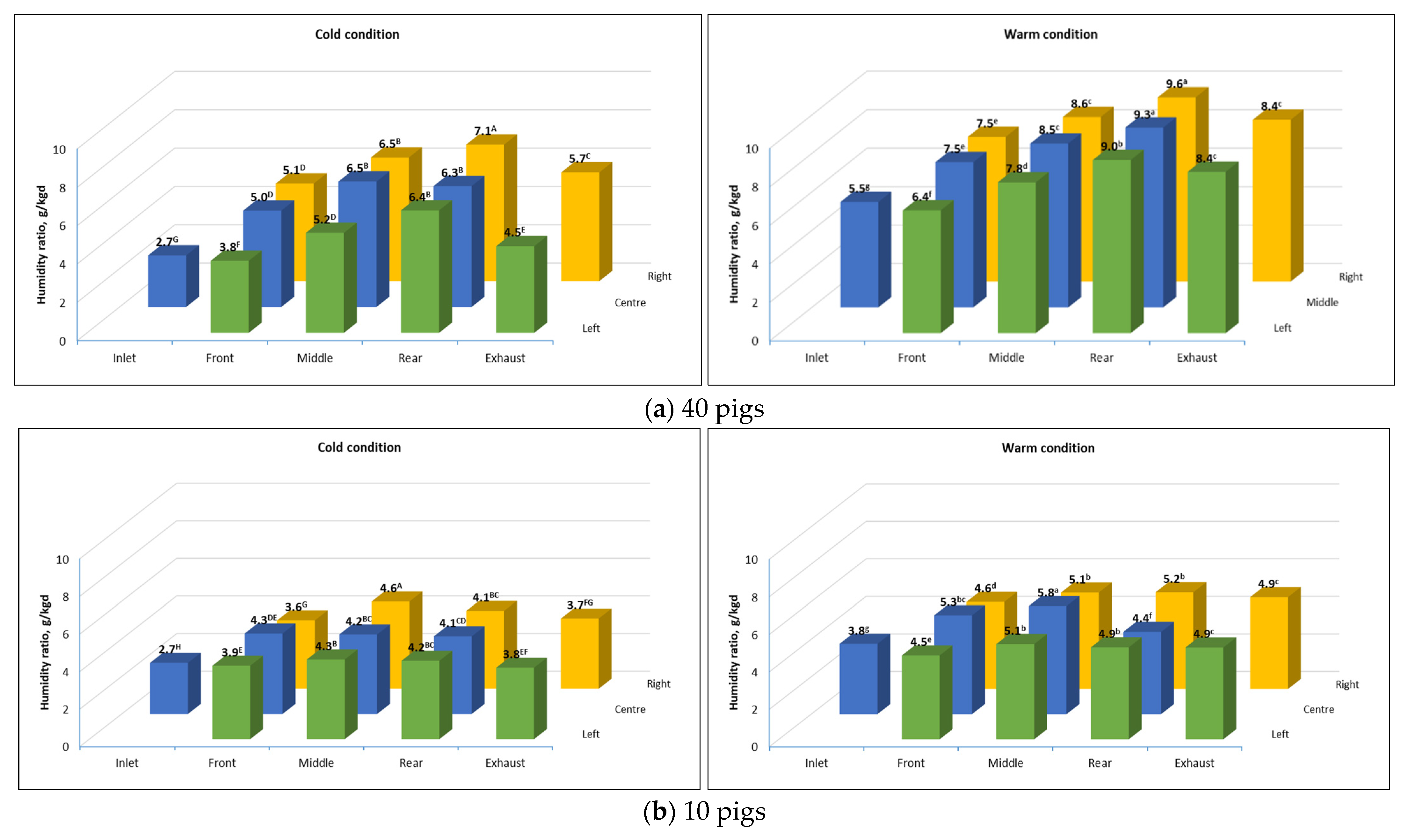

3.2.2. Average Humidity Ratio During the Stable Transport Period

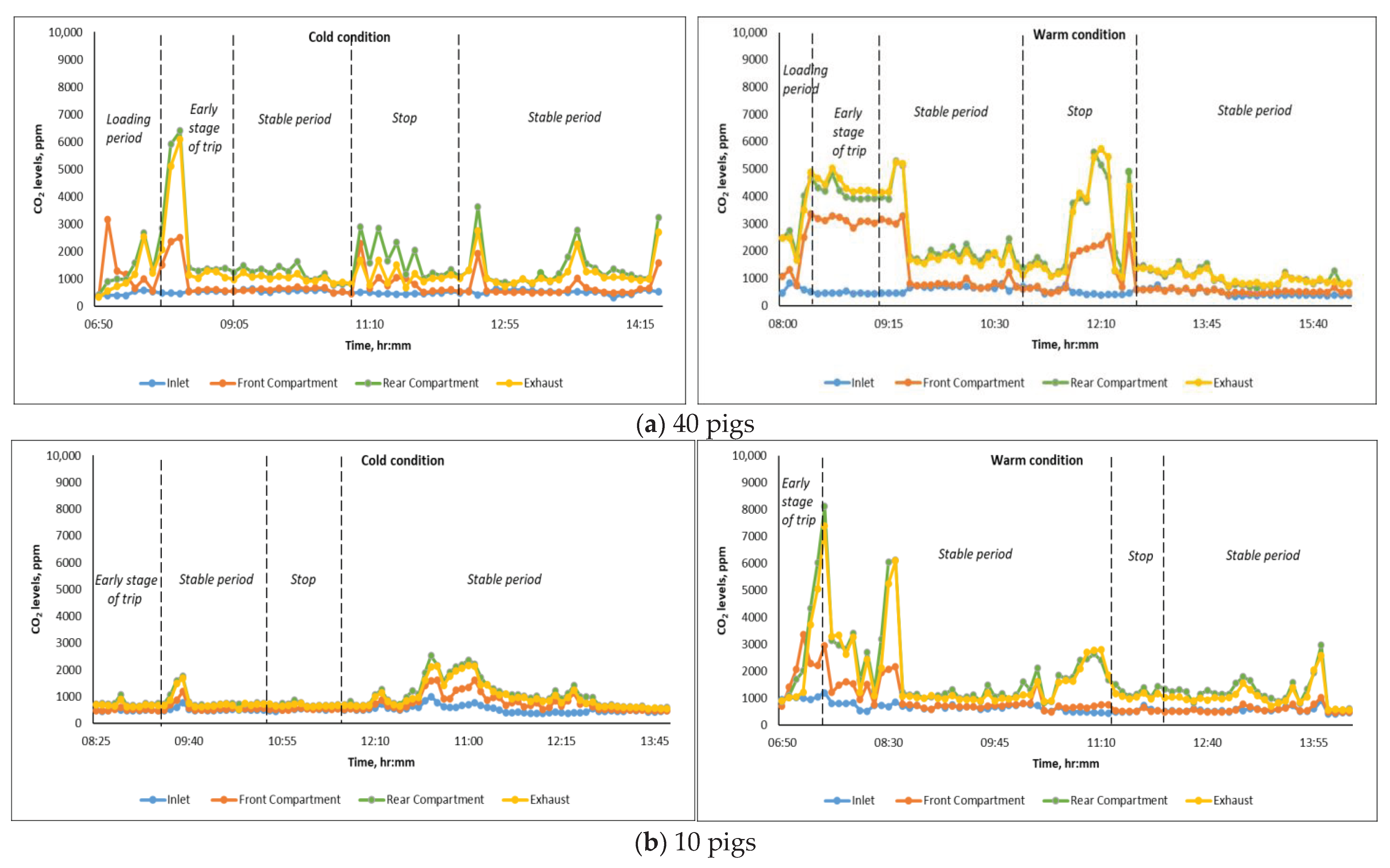

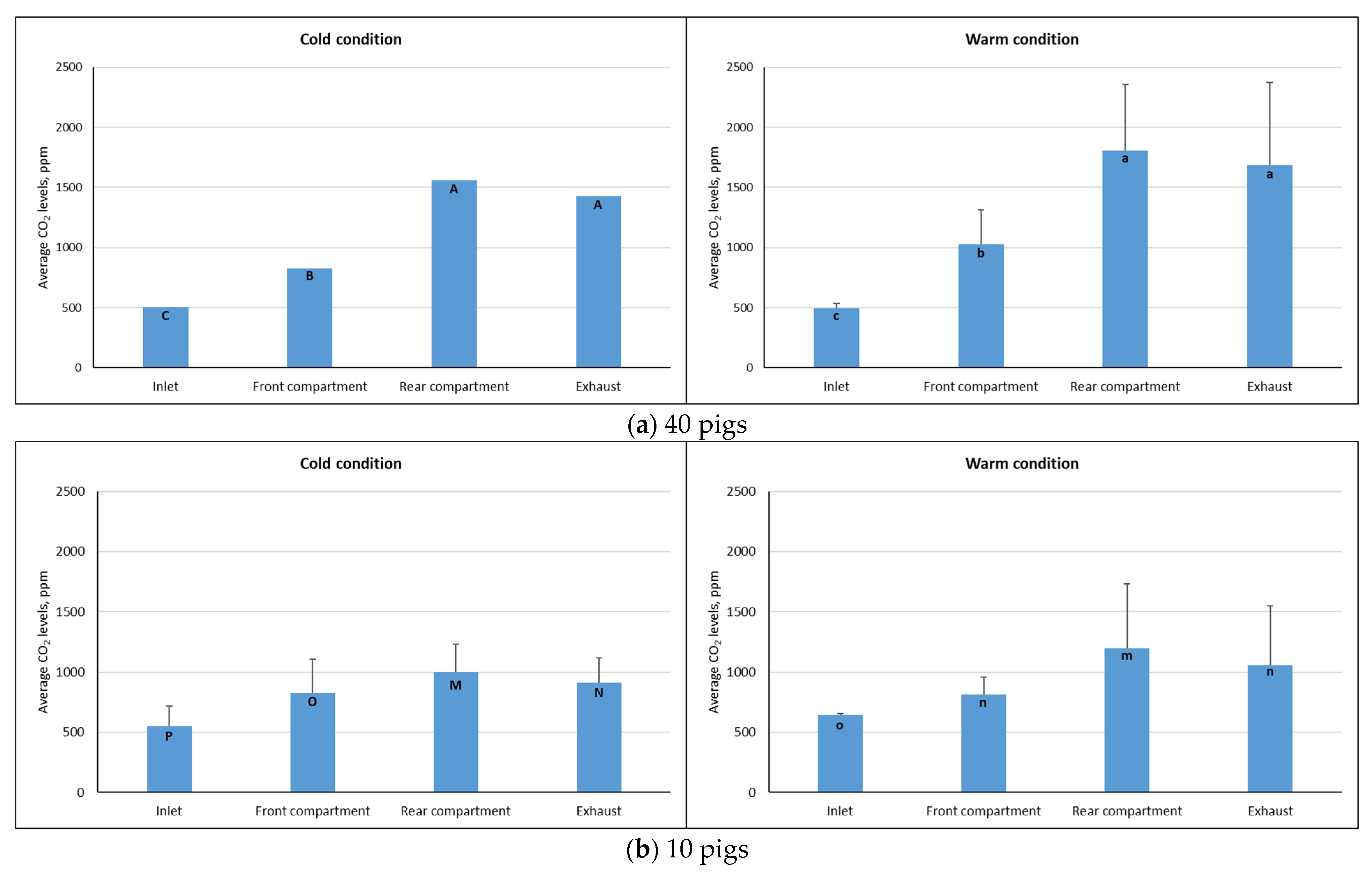

3.3. Carbon Dioxide Levels and Distribution

3.3.1. Carbon Dioxide Levels for the Entire Transport

3.3.2. Carbon Dioxide Levels During the Stable Transport Period

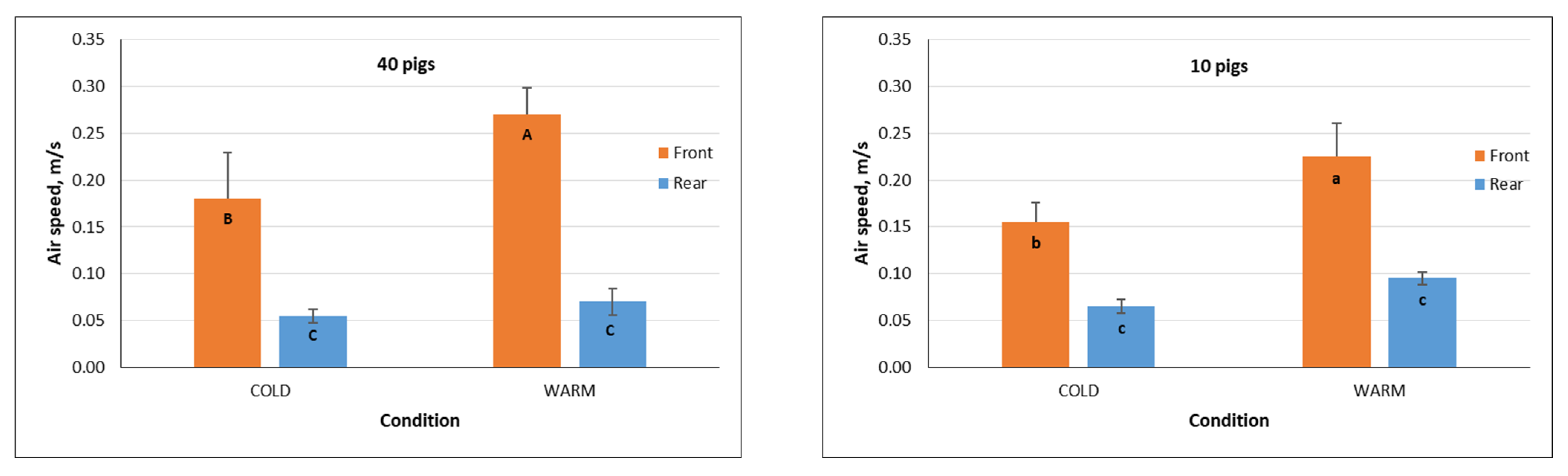

3.4. Air Speed

3.5. Animal Welfare

4. Discussion

4.1. Temperature Distribution and Thermal Comfort Classification

4.2. Moisture Levels and Distribution

4.3. Carbon Dioxide Levels and Distribution

4.4. Animal Welfare

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| DOA | Dead on arrival |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| RH | Relative humidity |

References

- Rioja-Lang, F.C.; Brown, J.A.; Brockhoff, E.J.; Faucitano, L. A review of swine transportation research on priority welfare issues: A Canadian perspective. Front. Vet. Sc. 2019, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumon, S.; Faucitano, L. Influence of loading handling and facilities on the subsequent response to pre-slaughter stress in pigs. Livest. Sci. 2017, 200, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, D.M. The effects of transport on animal welfare. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2005, 24, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrey, S.; Bergeron, R.; Faucitano, L.; Widowski, T.; Lewis, N.; Crowe, T.; Correa, J.A.; Brown, J.; Hayne, S.; Gonyou, H.W. Transportation of market-weight pigs: II. Effect of season and location within truck on behavior with an eight-hour transport. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 2872–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weschenfelder, A.V.; Torrey, S.; Devillers, N.; Crowe, T.; Bassols, A.; Saco, Y.; Piñeiro, M.; Saucier, L.; Faucitano, L. Effects of trailer design on animal welfare parameters and carcass and meat quality of three Pietrain crosses being transported over a long distance. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 3220–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A.; Samarakone, T.S.; Crowe, T.; Bergeron, R.; Widowski, T.; Correa, J.A.; Faucitano, L.; Torrey, S.; Gonyou, H.W. Temperature and humidity conditions in trucks transporting pigs in two seasons in eastern and western Canada. Trans. ASABE 2011, 54, 2311–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.; Dybkjær, L.; Herskin, M. Road transport of farm animals: Effects of journey duration on animal welfare. Animals 2011, 5, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilcher, C.M.; Ellis, M.; Rojo-Gómez, A.; Curtis, S.E.; Wolter, B.F.; Peterson, C.M.; Ritter, M.J.; Brinkmann, J. Effects of floor space during transport and journey time on indicators of stress and transport losses of market-weight pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 3809–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averos, X.; Herranz, A.; Sanchez, R.; Comella, J.; Gosalvez, L. Serum stress parameters in pigs transported to slaughter under commercial conditions in different seasons. Vet. Med. 2007, 52, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M.J.; Ellis, M.; Brinkmasnn, J.; DeCecker, J.M.; Keffaber, K.K.; Kocher, M.E.; Peterson, B.A.; Schlipf, J.M.; Wolter, B.F. Effect of floor space during transport of market-weight pigs on the incidence of transport losses at the packing plant and the relationships between transport conditions and losses. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 2856–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speer, N.C.; Slack, G.; Troyer, E. Economic factors associated with livestock transportation. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 79, E166–E170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M.J.; Ellis, M.; Berry, N.L.; Curtis, S.E.; Anil, L.; Berg, E.; Benjamin, M.; Butler, D.; Dewey, C.; Driessen, B.; et al. Review: Transport losses in market weight pigs: I. A review of definitions, incidence, and economic impact. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2009, 25, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.; Gonyou, H.; Torrey, S.; Widowski, T.; Bergeron, R.; Crowe, T.; Laforest, J.-P.; Faucitano, L. Welfare of pigs being transported over long distances using a pot-belly trailer during winter and summer. Animals 2014, 4, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kettlewell, P.J.; Hampson, C.J.; Green, N.R.; Teer, N.J. Heat and Moisture Generation of Livestock during Transportation. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Livestock Environment, Louisville, KY, USA, 21–23 May 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.; Wang, X.; Funk, T.; Wolter, B.; Murphy, C.; Lenkaitis, A.; Sun, Y.; Pilcher, C. Development of Improved Trailer Designs and Transport Management Practices That Create the Optimum Environment for Market Weight Pigs During Transport and Minimize Transport Losses; National Pork Board Pork Checkoff Animal Welfare Research Report; National Pork Board: Des Moines, IA, USA, 2008; Available online: https://porkcheckoff.org/research/development-of-improved-trailer-designs-and-transport-management-practices-that-create-the-optimum-environment-for-market-weight-pigs-during-transport-and-minimize-transport-losses/ (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Fox, J. The Effect of Water Sprinkling Market Pigs Transported During Summer on Pig Behavior, Gastrointestinal Tract Temperature and Trailer Micro-Climate. Master’s Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McGlone, J.; Johnson, A.; Sapkota, A.; Kephart, R. Temperature and relative humidity inside trailers during finishing pig loading and transport in cold and mild weather. Animals 2014, 4, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, J.; Sapkota, A.; Johnson, A.; Kephart, R. Establishing trailer ventilation (boarding) requirements for finishing pigs during transport. Animals 2014, 4, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Pork Council (CPC). Pig Transport Stocking Density. 2022. Available online: https://www.cpc-ccp.com/file.aspx?id=a8a17b90-5c8e-4e84-99d3-431868b306e8 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Albright, L.D. Ventilation rates. In Environment Control for Animals and Plants, 1st ed.; American Society of Agricultural Engineers: St Joseph, MI, USA, 1990; Volume 1, pp. 180–181. [Google Scholar]

- Cabahug, J. Evaluation of a Prototype Mechanically Ventilated Swine Transport Trailer Fitter with Air Filtration System. Master’s Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Green, A.; Gates, R. Characteristics of trailer thermal environment during commercial swine transport managed under U.S. industry guidelines. Animals 2015, 5, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC). Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pigs: Review of Scientific Research on Priority Issues. Available online: https://www.nfacc.ca/pdfs/codes/pig_code_of_practice.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Papatsiros, V.G.; Maragkakis, G.; Papakonstantinou, G.I. Stress biomarkers in pigs: Current insights and clinical application. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, C.E.; Straw, B.E. Herd examination. In Diseases of Swine, 9th ed.; Straw, B.E., Zimmerman, J.J., D’Alliare, S., Taylor, D.J., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, J.D.; Hoff, S.J.; Baas, T.J.; Zhao, Y.; Xin, H.; Follett, L.R. Evaluation of conditions during weaned pig transport. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2017, 33, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, E.; Deprez, K.; Beckers, F.; De Baerdemaeker, J.; Aubert, A.; Geers, R. Effect of driver and driving style on the stress responses of pigs during a short journey by trailer. Anim. Welf. 2008, 17, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.A.; Kettlewell, P.J. Engineering and design of vehicles for long distance road transport of livestock (ruminants, pigs and poultry). Vet. Ital. 2008, 44, 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y. Evaluation of Trailer Thermal Environment During Commercial Swine Transport. Master’s Thesis, University of Illinois, Champaign, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Costa, O.A.; Faucitano, L.; Coldebella, A.; Ludke, J.V.; Peloso, J.V.; Dalla Roza, D.; Paranhos Da Costa, M.J.R. Effects of the season of the year, truck type and location on truck on skin bruises and meat quality in pigs. Livest. Sci. 2007, 107, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predicala, B.; Alvarado, A.; Cabahug, J.; Kirychuk, S. Reducing Pathogen Distribution from Animal Transportation; ADF Project #20140282 Final Report; Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture: Regina, SK, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://agriculturereports.saskatchewan.ca/ADF/ADF_Admin/Reports/20140282.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Sommavilla, R.; Faucitano, L.; Gonyou, H.; Seddon, Y.; Bergeron, R.; Widowski, T.; Crowe, T.; Connor, L.; Scheeren, M.; Goumon, S.; et al. Season, transport duration and trailer compartment effects on blood stress indicators in pigs: Relationship to environmental, behavioral and other physiological factors, and pork quality traits. Animals 2017, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warriss, P.D.; Brown, S.N.; Knowles, T.G.; Wilkins, L.J.; Pope, S.J.; Chadd, S.A.; Kettlewell, P.J.; Green, N.R. Comparison of the effects of fan-assisted and natural ventilation of vehicles on the welfare of pigs being transported to slaughter. Vet. Rec. 2006, 158, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goumon, S.; Brown, J.A.; Faucitano, L.; Bergeron, R.; Widowski, T.M.; Crowe, T.; Connor, M.L.; Gonyou, H.W. Effects of transport duration on maintenance behavior, heart rate and gastrointestinal tract temperature of market-weight pigs in 2 seasons. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 4925–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Monitoring Trips | Blood Cortisol, nmol/L | Rectal Temperature, °C | Body Temperature, °C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | Start | End | Start | End | |

| 1 | 82.3 ± 40.2 | 72.0 ± 21.6 | 39.4 ± 0.5 | 38.1 ± 0.7 | 32.9 ± 1.4 | 35.1 ± 0.7 |

| 2 | 109.0 ± 57.5 | 114.8 ± 57.5 | 38.9 ± 0.3 | 39.2 ± 0.4 | 33.4 ± 0.8 | 34.0 ± 0.9 |

| 3 | 148.0 ± 35.0 | 81.7 ± 40.6 | 39.7 ± 0.4 | 39.6 ± 0.3 | 34.1 ± 1.4 | 39.6 ± 0.2 |

| 4 | - | - | 39.8 ± 0.3 | 39.6 ± 0.3 | 32.0 ± 1.2 | 33.5 ± 1.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alvarado, A.; Baguindoc, M.; Bolo, R.; Kirychuk, S.; Predicala, B. Performance Evaluation of Fan-Ventilated Swine Trailer with Air Filtration for Maintaining Satisfactory Transport Conditions. Animals 2026, 16, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010083

Alvarado A, Baguindoc M, Bolo R, Kirychuk S, Predicala B. Performance Evaluation of Fan-Ventilated Swine Trailer with Air Filtration for Maintaining Satisfactory Transport Conditions. Animals. 2026; 16(1):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010083

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarado, Alvin, Marjorette Baguindoc, Roger Bolo, Shelley Kirychuk, and Bernardo Predicala. 2026. "Performance Evaluation of Fan-Ventilated Swine Trailer with Air Filtration for Maintaining Satisfactory Transport Conditions" Animals 16, no. 1: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010083

APA StyleAlvarado, A., Baguindoc, M., Bolo, R., Kirychuk, S., & Predicala, B. (2026). Performance Evaluation of Fan-Ventilated Swine Trailer with Air Filtration for Maintaining Satisfactory Transport Conditions. Animals, 16(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010083