Smaller Size of Nesting Loggerhead Sea Turtles in Northwest Florida

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

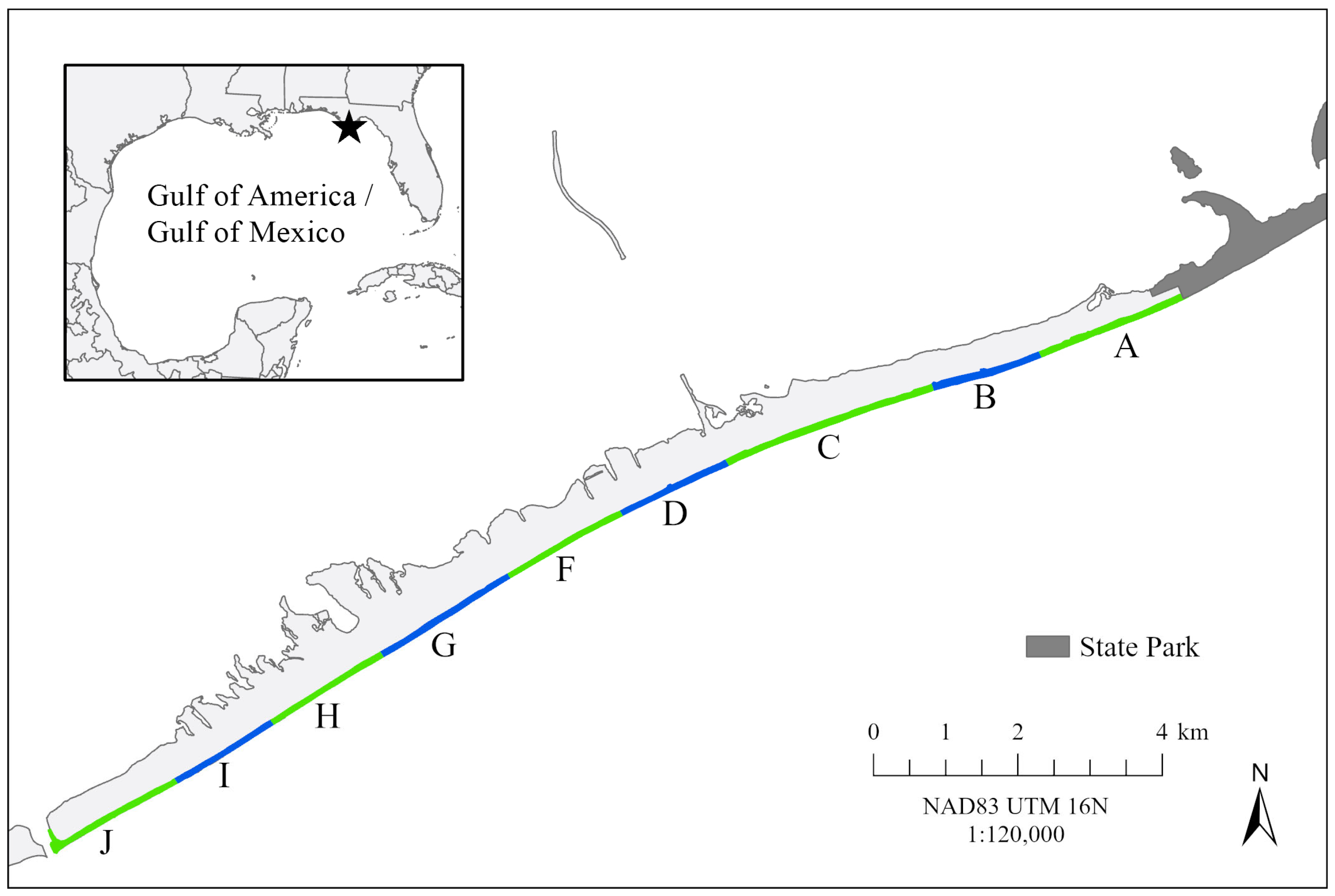

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Beach Surveys

2.3. Statistical and GIS Analyses

3. Results

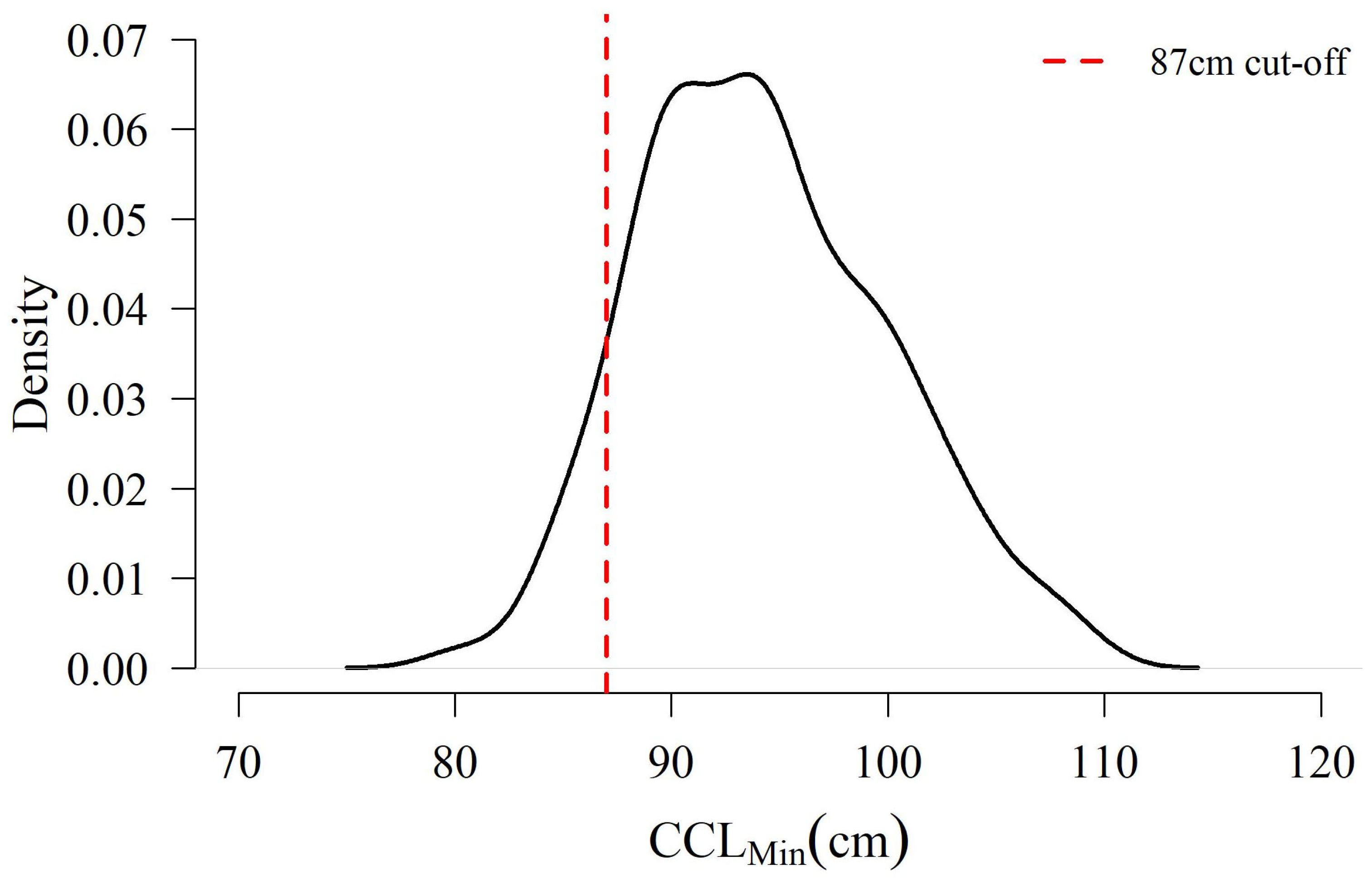

3.1. Proportion of Females < 87 cm CCLmin

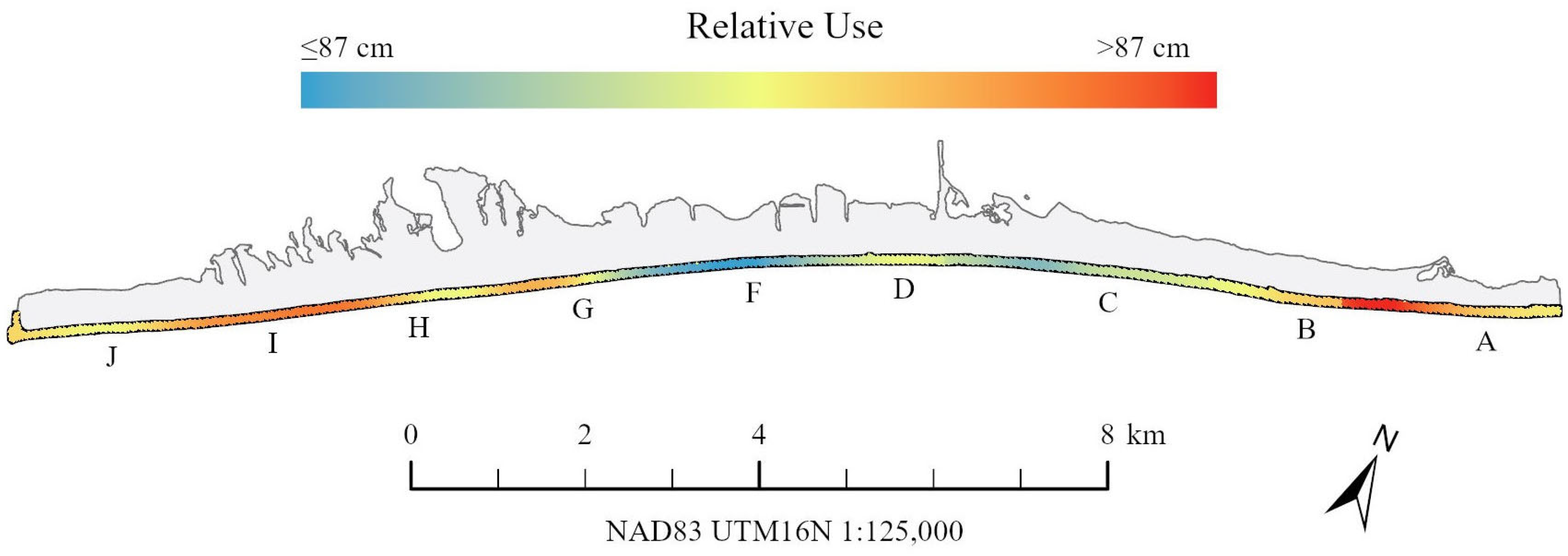

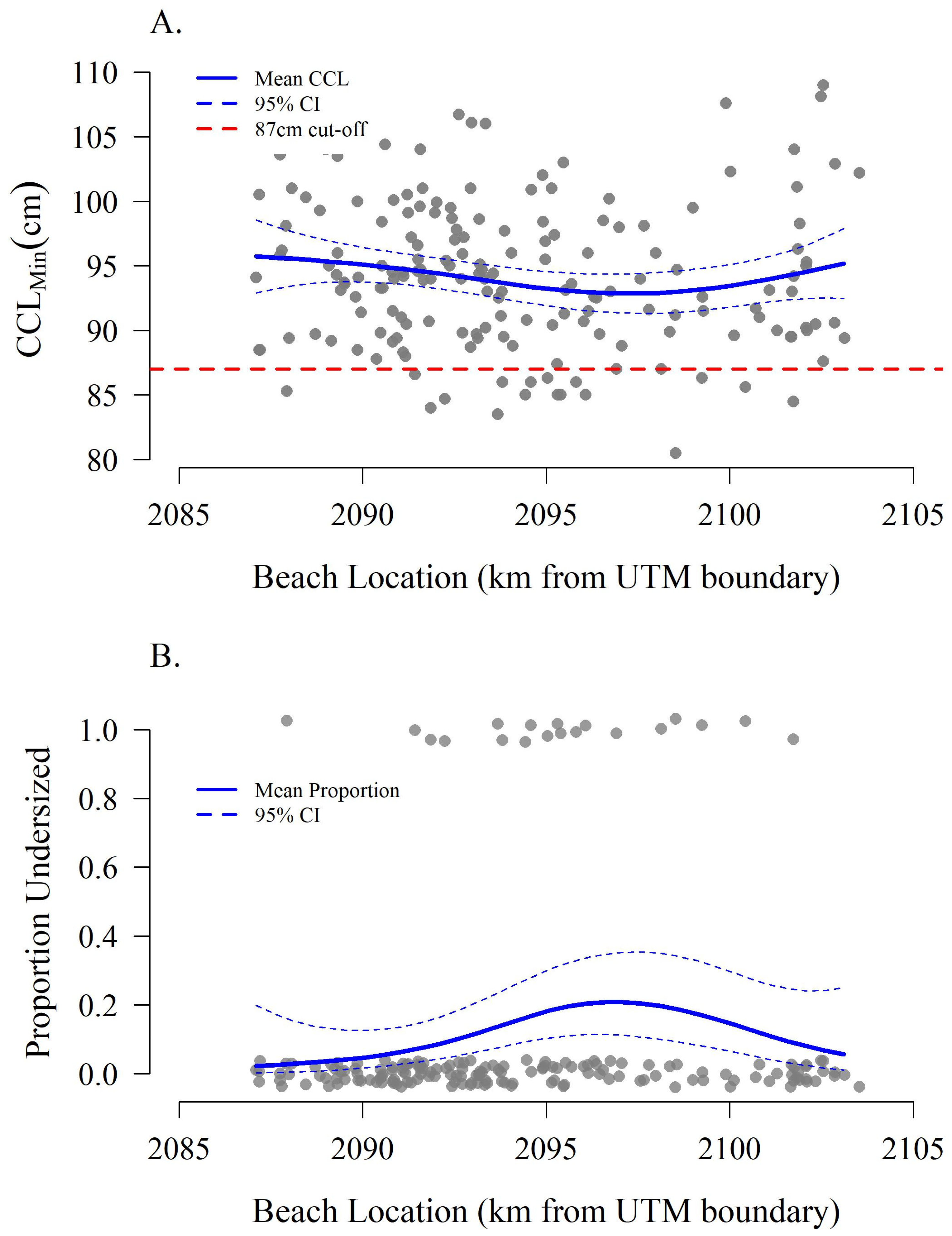

3.2. Spatial Emergence Patterns

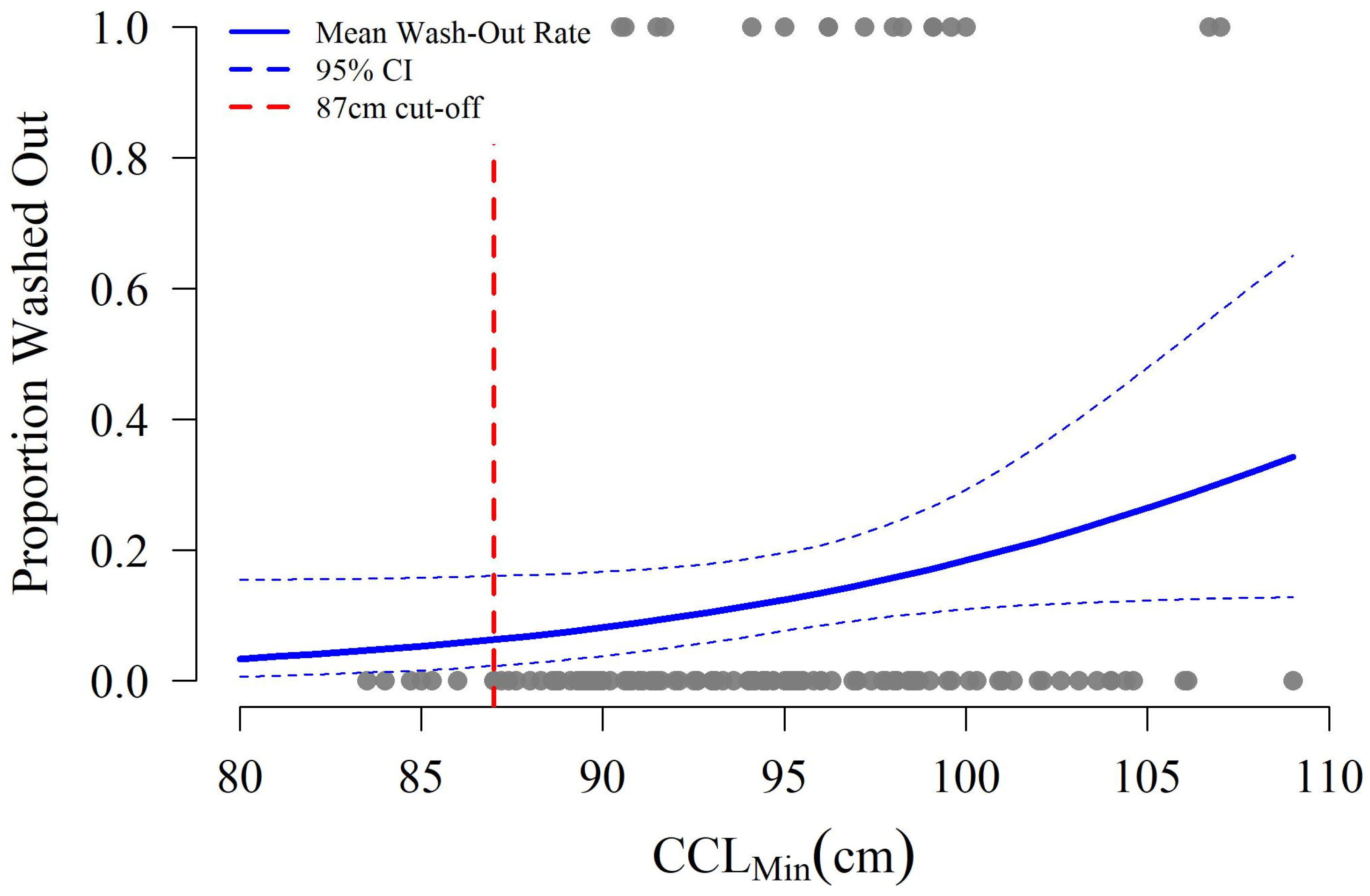

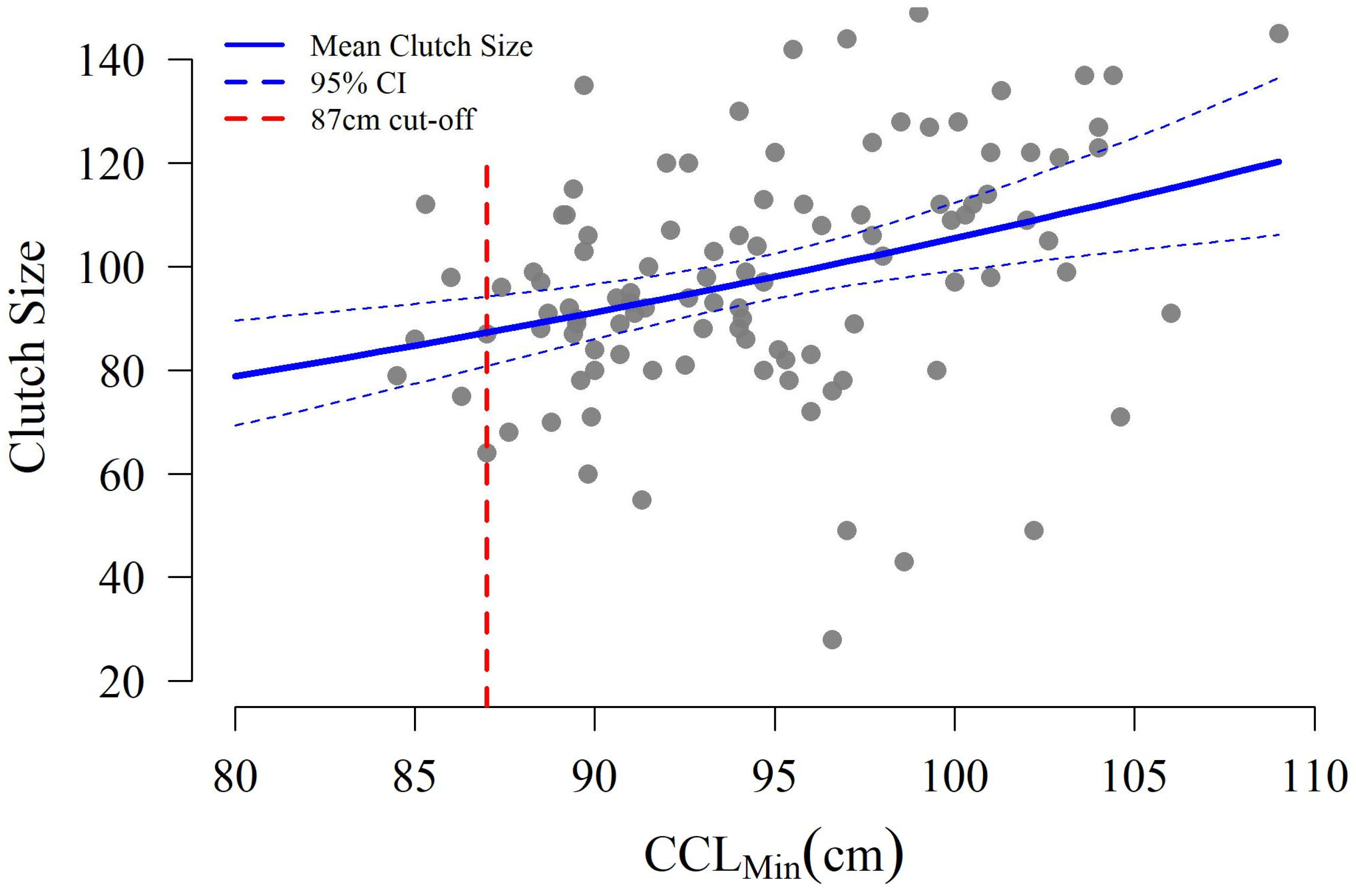

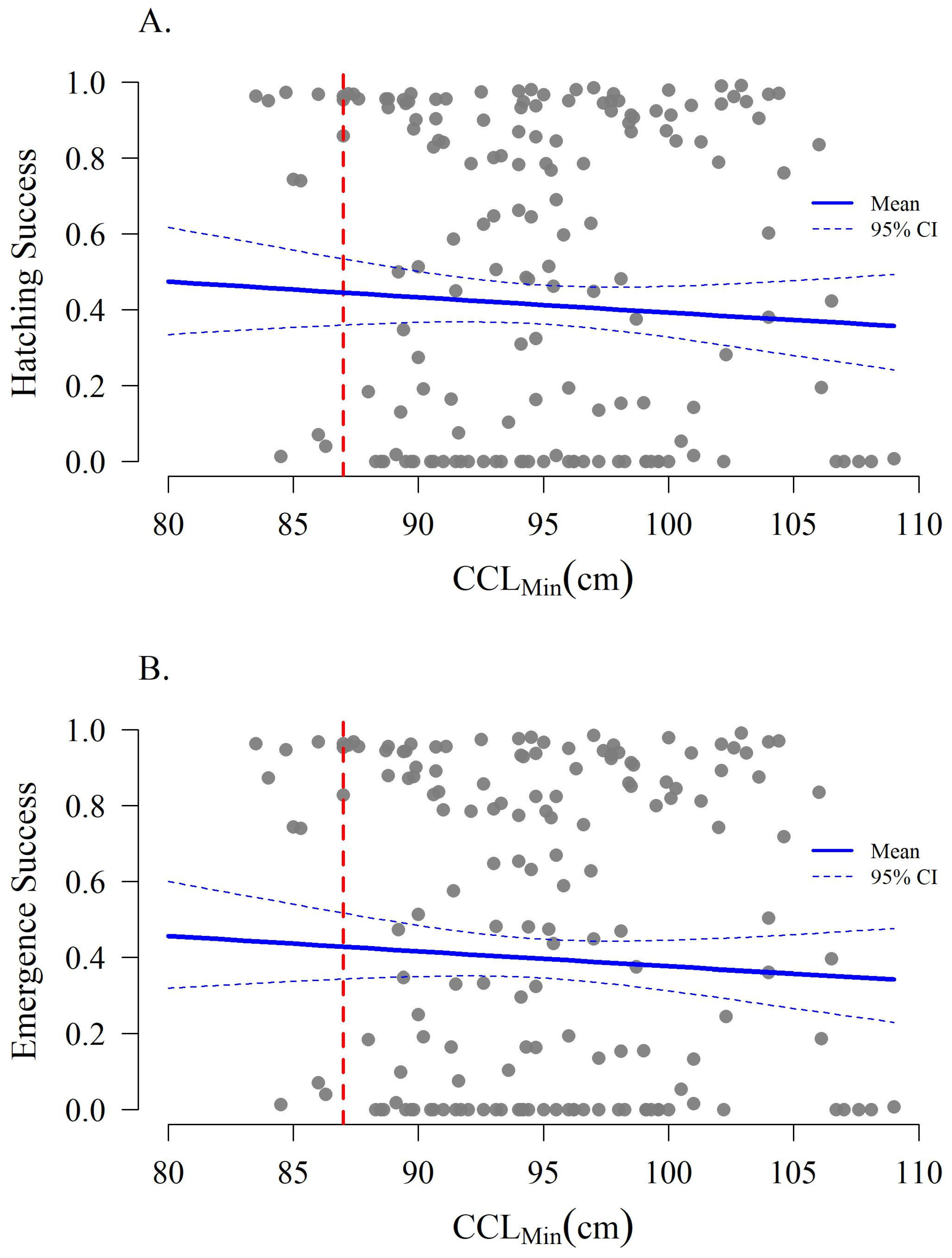

3.3. Hatchling Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCLmin | Minimum curved carapace length |

| FSU MTRECG | Florida State University Marine Turtle Research, Ecology, and Conservation Group |

Appendix A

| Zone | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2021 | 2022 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 13 | 0 | 28 |

| B | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 87 |

| C | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 59 |

| D | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 87 |

| F | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 87 |

| G | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 87 |

| H | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 87 |

| I | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 87 |

| J | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 0 | 80 |

References

- Blanckenhorn, W.U. Behavioral Causes and Consequences of Sexual Size Dimorphism. Ethology 2005, 111, 977–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsbeek, R. Experimental Evidence That Competition and Habitat Use Shape the Individual Fitness Surface. J. Evol. Biol. 2009, 22, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnick, S.; Di Stefano, J.; Elgar, M.A.; Coulson, G. Inter- and Intraspecific Effects of Body Size on Habitat Use among Sexually-Dimorphic Macropodids. Oikos 2014, 123, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, S.R.; Silla, A.J.; Dingemanse, N.J.; Byrne, P.G. Body Size Predicts Between-Individual Differences in Exploration Behaviour in the Southern Corroboree Frog. Anim. Behav. 2017, 129, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, L.; De Roos, A.M. Adaptive Habitat Use in Size-Structured Populations: Linking Individual Behavior to Population Processes. Ecology 2003, 84, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tershy, B.R. Body Size, Diet, Habitat Use, and Social Behavior of Balaenoptera Whales in the Gulf of California. J. Mammal. 1992, 73, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, M.J.; Harvey, J.T.; Costa, D.P. The Role of Body Size in Individual-Based Foraging Strategies of a Top Marine Predator. Ecology 2010, 91, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, D.T.; Crowder, L.B.; Caswell, H. A Stage-based Population Model for Loggerhead Sea Turtles and Implications for Conservation. Ecology 1987, 68, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, L.B.; Crouse, D.T.; Heppell, S.S. Predicting the Impact of Turtle Excluder Devices on Loggerhead Sea Turtle Populations. Ecol. Appl. 1994, 4, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppell, S.S.; Crowder, L.B.; Crouse, D.T.; Epperley, S.P.; Frazier, N.B. Population Models for Atlantic Loggerheads: Past, Present, and Future. In Loggerhead Sea Turtles; Bolten, A.B., Witherington, B.E., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Piacenza, S.E.; Balazs, G.H.; Hargrove, S.K.; Richards, P.M.; Heppell, S.S. Trends and Variability in Demographic Indicators of a Recovering Population of Green Sea Turtles Chelonia Mydas. Endanger. Species Res. 2016, 31, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorndal, K.A.; Bowen, B.W.; Chaloupka, M.Y.; Crowder, L.B.; Heppell, S.S.; Jones, C.M.; Lutcavage, M.E.; Solow, A.R.; Witherington, B.E. Assessment of Sea-Turtle Status and Trends: Integrating Demography and Abundance; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorndal, K.A.; Parsons, J.; Mustin, W.; Bolten, A.B. Variation in Age and Size at Sexual Maturity in Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtles. Endanger. Species Res. 2014, 25, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, J.M.; Haas, H.L.; Richards, P.M.; Rose, K.A. Life-history Constraints on Maximum Population Growth for Loggerhead Turtles in the Northwest Atlantic. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 9442–9452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heppell, S.S.; Caswell, H.; Crowder, L.B. Life Histories and Elasticity Patterns: Perturbation Analysis for Species with Minimal Demographic Data. Ecology 2000, 81, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avens, L.; Lamont, M.M.; Foley, A.M.; Higgins, B.M.; Howell, L.N.; Lovewell, G.; Shaver, D.J.; Stacy, B.A.; Walker, J.S.; Clark, J.M.; et al. Regional Differentiation in Somatic Growth and Maturation Attributes for Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta) in the Northwest Atlantic. Mar. Biol. 2025, 172, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, C.R.; Robinson, N.J.; Spotila, J.R.; Paladino, F.V.; Santidrián Tomillo, P. Body Size Constrains Maternal Investment in a Small Sea Turtle Species. Mar. Biol. 2020, 167, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, G.C.; Taxonera, A.; Renom, B.; Fairweather, K.; Lopes, A.; Cozens, J.; Laloë, J.-O. Changes in Mean Body Size in an Expanding Population of a Threatened Species. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 289, 20220696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heithaus, M.R.; Frid, A.; Dill, L.M. Shark-Inflicted Injury Frequencies, Escape Ability, and Habitat Use of Green and Loggerhead Turtles. Mar. Biol. 2002, 140, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buskirk, J.; Crowder, L.B. Life-History Variation in Marine Turtles. Copeia 1994, 1994, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Mohapatra, S.K.; Tripathy, B.; Swain, A.; Mohapatra, A. Do Olive Ridley Turtles Select Mates Based on Size? An Investigation of Mate Size Preference at a Major Arribada Rookery. Ecosphere 2025, 16, e70264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avens, L.; Ramirez, M.D.; Hall, A.G.; Snover, M.L.; Haas, H.L.; Godfrey, M.H.; Goshe, L.R.; Cook, M.; Heppell, S.S. Regional Differences in Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle Growth Trajectories and Expected Age at Maturation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2020, 654, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorndal, K.A.; Bowen, B.W.; Chaloupka, M.Y.; Crowder, L.B.; Heppell, S.S.; Jones, C.M.; Lutcavage, M.E.; Policansky, D.; Solow, A.R.; Witherington, B.E. Better Science Needed for Restoration in the Gulf of Mexico. Science 2011, 331, 537–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casale, P.; Heppell, S.S. How Much Sea Turtle Bycatch Is Too Much? A Stationary Age Distribution Model for Simulating Population Abundance and Potential Biological Removal in the Mediterranean. Endanger. Species Res. 2016, 29, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppell, S.S.; Crouse, D.T.; Crowder, L.B.; Epperly, S.P.; Gabriel, W.; Henwood, T.; Marquez, R.; Thompson, N.B. A Population Model to Estimate Recovery Time, Population Size, and Management Impacts on Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtles. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2005, 4, 767–773. [Google Scholar]

- Piacenza, S.E.; Richards, P.M.; Heppell, S.S. Fathoming Sea Turtles: Monitoring Strategy Evaluation to Improve Conservation Status Assessments. Ecol. Appl. 2019, 29, e01942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, C.; McMichael, E.; Witherington, B.E.; Foley, A.M.; Hardy, R.; Meylan, A.B. In-Water Sea Turtle Research in Florida: Review and Recommendations; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, K.L.; Wyneken, J.; Luo, J. First Atlantic Satellite Tracks of “lost Years” Green Turtles Support the Importance of the Sargasso Sea as a Sea Turtle Nursery. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 288, 20210057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, H.J.; Mortimer, J.A.; Laloë, J.-O.; Hays, G.C.; Esteban, N. Synergistic Use of UAV Surveys, Satellite Tracking Data, and Mark-recapture to Estimate Abundance of Elusive Species. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, I.P.; Meager, J.J.; Eguchi, T.; Dobbs, K.A.; Miller, J.D.; Madden Hof, C.A. Twenty-Eight Years of Decline: Nesting Population Demographics and Trajectory of the North-East Queensland Endangered Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Castro, M.C.; Cuevas, E.; Guzmán Hernández, V.; Raymundo Sánchez, Á.; Martínez-Portugal, R.C.; Reyes, D.J.L.; Chio, J.Á.B. Trends in Reproductive Indicators of Green and Hawksbill Sea Turtles over a 30-Year Monitoring Period in the Southern Gulf of Mexico and Their Conservation Implications. Animals 2022, 12, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, J.A.; Appoo, J.; Bautil, B.; Betts, M.; Burt, A.J.; Chapman, R.; Currie, J.C.; Doak, N.; Esteban, N.; Liljevik, A.; et al. Long-Term Changes in Adult Size of Green Turtles at Aldabra Atoll and Implications for Clutch Size, Sexual Dimorphism and Growth Rates. Mar. Biol. 2022, 169, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.F.; Stahelin, G.D.; Chabot, R.M.; Mansfield, K.L. Long-Term Trends in Marine Turtle Size at Maturity at an Important Atlantic Rookery. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.R.; Johnson, C.; Godfrey, M.H. The Minimum Size of Leatherbacks at Reproductive Maturity, with a Review of Sizes for Nesting Females from the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean Basins. Herpetol. J. 2007, 17, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, G.C.; Rusli, M.U.; Booth, D.; Laloë, J.O. Global Decline in the Size of Sea Turtles. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, M.H.; Berkson, J.; Rivalan, P. Estimating Demographic Parameters for Loggerhead Sea Turtles Using Mark-Recapture Data and a Multistate Model. Popul. Ecol. 2010, 53, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turtle Expert Working Group. An Assessment of the Loggerhead Turtle Population in the Western North Atlantic Ocean; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Miami, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Avens, L.; Snover, M.L. Age and Age Estimation in Sea Turtles. In The Biology of Sea Turtles, Volume 3; Wyneken, J., Lohmann, K.J., Musick, J.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 97–133. [Google Scholar]

- Piovano, S.; Clusa, M.; Carreras, C.; Giacoma, C.; Pascual, M.; Cardona, L. Different Growth Rates between Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta) of Mediterranean and Atlantic Origin in the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Biol. 2011, 158, 2577–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, D.; Walters, R.; Gotthard, K. What Limits Insect Fecundity? Body Size- and Temperature-Dependent Egg Maturation and Oviposition in a Butterfly. Funct. Ecol. 2008, 22, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, J.; Beranek, C.; Valdez, J.; Mahony, M. Quantity versus Quality: A Balance between Egg and Clutch Size among Australian Amphibians in Relation to Other Life-History Variables. Austral Ecol. 2022, 47, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honěk, A. Intraspecific Variation in Body Size and Fecundity in Insects: A General Relationship. Oikos 1993, 66, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, H. Life History Patterns in Female Moose (Alces alces): The Relationship between Age, Body Size, Fecundity and Environmental Conditions. Oecologia 1996, 106, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.C.; Rusli, M.U.; Broderick, A.C.; Barneche, D.R. Size Scaling of Sea Turtle Reproduction May Reconcile Fundamental Ecology and Conservation Strategies at the Global Scale. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, A.C.; Glen, F.; Godley, B.J.; Hays, G.C. Variation in Reproductive Output of Marine Turtles. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2003, 288, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gouvello, D.Z.M.; Nel, R.; Cloete, A.E. The Influence of Individual Size on Clutch Size and Hatchling Fitness Traits in Sea Turtles. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2020, 527, 151372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Marine Fisheries Service; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery Plan for the Northwest Atlantic Population of the Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta), Second Revision; National Marine Fisheries Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, M.D.; Schwenter, J.A.; Owens, D.W. Climate-Mediated Population Dynamics for the World’s Most Endangered Sea Turtle Species. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazaris, A.D.; Matsinos, Y.G. An Individual Based Model of Sea Turtles: Investigating the Effect of Temporal Variability on Population Dynamics. Ecol. Model. 2006, 194, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacenza, S.E.; Richards, P.M.; Heppell, S.S. An Agent-Based Model to Evaluate Recovery Times and Monitoring Strategies to Increase Accuracy of Sea Turtle Population Assessments. Ecol. Model. 2017, 358, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, J. Maternal Effects in Animal Ecology. Am. Zool. 1996, 36, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gouvello, D.Z.M.; Girondot, M.; Bachoo, S.; Nel, R. The Good and Bad News of Long-Term Monitoring: An Increase in Abundance but Decreased Body Size Suggests Reduced Potential Fitness in Nesting Sea Turtles. Mar. Biol. 2020, 167, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, A.M.; Rostal, D.C.; Drake, K.K.; Williams, K.L.; Frick, M.G.; Robinette, J.; Barnard-Keinath, D.E. The Influence of Maternal Size on the Eggs and Hatchlings of Loggerhead Sea Turtles. Southeast. Nat. 2014, 13, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherington, B.E. Human and Natural Causes of Marine Turtle Clutch and Hatchling Mortality and Their Relationship to Hatchling Production on an Important Florida Nesting Beach. Master’s Thesis, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, S.J.; Mrosovsky, N. Nest Site Selection in Leatherbacks, Dermochelys coriacea: Individual Patterns and Their Consequences. Anim. Behav. 2004, 68, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Abella, E.; Martins, S.; López, O.; Patino-Martinez, J. Female Nesting Behaviour Affects Hatchling Survival and Sex Ratio in the Loggerhead Sea Turtle: Implications for Conservation Programmes. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 30, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, A.R.; Varela, M.R.; Barbosa, C.; Broderick, A.C.; Ferreira Airaud, M.B.; Godley, B.J.; Regalla, A.; Tilley, D.; Catry, P. Nest Site Selection Repeatability of Green Turtles, Chelonia mydas, and Consequences for Offspring. Anim. Behav. 2018, 139, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaller, J.B.; Limpus, C.J.; Bjorndal, K.A. Nest-Site Selection in Individual Loggerhead Turtles and Consequences for Doomed-Egg Relocation. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caughley, G. Directions in Conservation Biology. J. Anim. Ecol. 1994, 63, 215–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traill, L.W.; Brook, B.W.; Frankham, R.R.; Bradshaw, C.J.A. Pragmatic Population Viability Targets in a Rapidly Changing World. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorndal, K.A.; Bolten, A.B.; Koike, B.; Schroeder, B.A.; Shaver, D.J.; Teas, W.G.; Witzell, W.N. Somatic Growth Function for Immature Loggerhead Sea Turtles, Caretta caretta, in Southeastern U.S. Waters. Fish. Bull. 2001, 99, 240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, J.; Murphy, S.; Von Harten, A. Morphometric Analysis of the Northern Subpopulation of Caretta caretta in South Carolina, USA. Mar. Turt. Newsl. 2005, 107, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart, L.M. A Continuation of Base-Line Studies for Environmentally Monitoring Space Transport Systems at John F. Kennedy Space Center. Volume 4: Threatened and Endangered Species of the Kennedy Space Center: Marine Turtle Studies; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Orlando, FL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, N.B. Demography and Life History Evolution of the Atlantic Loggerhead Sea Turtle, Caretta caretta. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Benscoter, A.M.; Smith, B.J.; Hart, K.M. Loggerhead Marine Turtles (Caretta caretta) Nesting at Smaller Sizes than Expected in the Gulf of Mexico: Implications for Turtle Behavior, Population Dynamics, and Conservation. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2022, 4, e581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriani, S.A.; Casale, P.; Brost, M.; Leone, E.H.; Witherington, B.E. Conservation Implications of Sea Turtle Nesting Trends: Elusive Recovery of a Globally Important Loggerhead Population. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobes, E.M.; Ware, M.; Beckwith, V.K.; Fuentes, M.M.P.B. Beach Crabbing as a Possible Hindrance to Loggerhead Marine Turtle Nesting Success. Mar. Turt. Newsl. 2019, 159, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- National Marine Fisheries Service; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta) Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; National Marine Fisheries Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson Sella, K.A.; Fuentes, M.M.P.B. Exposure of Marine Turtle Nesting Grounds to Coastal Modifications: Implications for Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 169, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver-Gorges, I.; Ceriani, S.A.; Ware, M.; Lamb, M.; Lamont, M.M.; Becker, J.; Carthy, R.R.; Matechik, C.; Mitchell, J.; Pruner, R.; et al. Using Systems Thinking to Inform Management of Imperiled Species: A Case Study with Sea Turtles. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 260, 109201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, M.; Ceriani, S.A.; Long, J.W.; Fuentes, M.M.P.B. Exposure of Loggerhead Sea Turtle Nests to Waves in the Florida Panhandle. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M.M.; Fujisaki, I.; Carthy, R.R. Estimates of Vital Rates for a Declining Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta) Subpopulation: Implications for Management. Mar. Biol. 2014, 161, 2659–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamblin, B.M.; Dodd, M.G.; Bagley, D.A.; Ehrhart, L.M.; Tucker, A.D.; Johnson, C.; Carthy, R.R.; Scarpino, R.A.; McMichael, E.; Addison, D.S.; et al. Genetic Structure of the Southeastern United States Loggerhead Turtle Nesting Aggregation: Evidence of Additional Structure within the Peninsular Florida Recovery Unit. Mar. Biol. 2011, 158, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Marine Turtle Conservation Handbook; Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.D. Determining Clutch Size and Hatching Success. In Research and Management Techniques for the Conservation of Sea Turtles; Eckert, K.L., Bjorndal, K.A., Abreu-Grobois, F.A., Donnelly, M., Eds.; IUCN/SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- National Marine Fisheries Southeast Fisheries Science Center. Sea Turtle Research Techniques Manual; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Miami, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, K.L.; Bjorndal, K.A.; Abreu-grobois, F.A.; Donnelly, M. (Eds.) Research and Management Techniques for the Conservation of Sea Turtles; Consolidated Graphic Communications: Blanchard, PA, USA, 1999; ISBN 2831703646. [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez, B. Morphological Variations in the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas): A Field Study on an Eastern Mediterranean Nesting Population. Zool. Stud. 2019, 58, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ArcGIS Pro, version 3.5.4; ESRI Inc.: Redlands, CA, USA, 2025.

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1986; ISBN 9780412246203. [Google Scholar]

- Derville, S.; Constantine, R.; Baker, C.S.; Oremus, M.; Torres, L.G. Environmental Correlates of Nearshore Habitat Distribution by the Critically Endangered Maui Dolphin. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2016, 551, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, M.; Long, J.W.; Fuentes, M.M.P.B. Using Wave Runup Modeling to Inform Coastal Species Management: An Example Application for Sea Turtle Nest Relocation. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 173, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benscoter, A.M.; Hart, K.M. Tagging Date, Site, Turtle Size, and Migration and Foraging Behavioral Data for Loggerheads (Caretta caretta) Nesting at Three Sites in the Gulf of Mexico from 2011–2019; Wetland and Aquatic Research Center: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goshe, L.R.; Avens, L.; Scharf, F.S.; Southwood, A.L. Estimation of Age at Maturation and Growth of Atlantic Green Turtles (Chelonia mydas) Using Skeletochronology. Mar. Biol. 2010, 157, 1725–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Cardona, L.; Abella, E.; Silva, E.; de Santos Loureiro, N.; Roast, M.; Marco, A. Effect of Body Size on the Long-Term Reproductive Output of East Atlantic Loggerhead Turtles Caretta caretta. Endanger. Species Res. 2022, 48, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.J.; Bobyn, M.L.; Galbraith, D.A.; Layfield, J.A.; Nancekivell, E.G. Maternal and Environmental Influences on Growth and Survival of Embryonic and Hatchling Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Can. J. Zool. 1991, 69, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.J.; Mrosovsky, N. Repeatability of Nesting Preferences in the Hawksbill Sea Turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, and Their Fitness Consequences. Anim. Behav. 2005, 70, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Patrício, A.R.; Clarke, L.J.; de Santos Loureiro, N.; Marco, A. High Variability in Nest Site Selection in a Loggerhead Turtle Rookery, in Boa Vista Island, Cabo Verde. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2022, 556, 151798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosenburg, W.M. Maternal Condition and Nest Site Choice: An Alternative for the Maintenance of Environmental Sex Determination? Am. Zool. 1996, 36, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpus, C.J.; Miller, J.D.; Pfaller, J.B. Flooding-Induced Mortality of Loggerhead Sea Turtle Eggs. Wildl. Res. 2020, 48, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.P.; von Holle, B.; Weishampel, J.F. Why Do Sea Turtle Nests Fail? Modeling Clutch Loss across the Southeastern United States. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.T.; Drye, B.; Domangue, R.J.; Paladino, F.V. Exploring the Role of Artificial Lighting in Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta) Nest-Site Selection and Hatchling Disorientation. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 13, 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Reising, M.; Salmon, M.; Stapleton, S.P. Hawksbill Nest Site Selection Affects Hatchling Survival at a Rookery in Antigua, West Indies. Endanger. Species Res. 2015, 29, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, E.; Wibbels, T.; Najera, B.M.Z.; Martinez, M.A.C.; Martinez, L.A.S.; Reyes, D.J.L.; Hernandez, M.H.; Gamez, D.G.; Pena, L.J.; Burchfield, P.M. In Situ Nest and Hatchling Survival at Rancho Nuevo, the Primary Nesting Beach of the Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle, Lepidochelys kempii. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 9, 563–577. [Google Scholar]

- Marco, A.; da Graça, J.; García-Cerdá, R.; Abella, E.; Freitas, R. Patterns and Intensity of Ghost Crab Predation on the Nests of an Important Endangered Loggerhead Turtle Population. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2015, 468, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, M.; Fuentes, M.M.P.B. A Comparison of Methods Used to Monitor Groundwater Inundation of Sea Turtle Nests. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2018, 503, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avens, L.; Goshe, L.R.; Coggins, L.; Shaver, D.J.; Higgins, B.M.; Landry, A.M., Jr.; Bailey, R. Variability in Age and Size at Maturation, Reproductive Longevity, and Long-Term Growth Dynamics for Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtles in the Gulf of Mexico. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorndal, K.A.; Bolten, A.B.; Dellinger, T.; Delgado, C.; Martins, H.R. Compensatory Growth in Oceanic Loggerhead Sea Turtles: Response to a Stochastic Environment. Ecology 2003, 84, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Bjorndal, K.A. Variation in Morphology and Reproduction in Loggerheads, Caretta caretta, Nesting in the United States, Brazil, and Greece. Herpetologica 2000, 56, 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Lagueux, C.J.; Campbell, C.L.; Strindberg, S. Artisanal Green Turtle, Chelonia mydas, Fishery of Caribbean Nicaragua: I. Catch Rates and Trends, 1991–2011. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Koch, V. Sea Turtle Consumption and Black Market Trade in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Endanger. Species Res. 2009, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, M.; Casale, P. Sea Turtle Bycatch and Consumption in Egypt Threatens Mediterranean Turtle Populations. Oryx 2011, 45, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.B.; Weber, N.; Ellick, J.; Avery, A.; Frauenstein, R.; Godley, B.J.; Sim, J.; Williams, N.; Broderick, A.C. Recovery of the South Atlantic’s Largest Green Turtle Nesting Population. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 3005–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, T.A.; Dutton, P.H.; Eguchi, T.; Epperly, S.P.; Fahy, C.C.; Godfrey, M.H.; MacPherson, S.L.; Possardt, E.E.; Schroeder, B.A.; Seminoff, J.A.; et al. Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta) 2009 Status Review Under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Report of the Biological Review Team to the National Marine Fisheries Service; National Marine Fisheries Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 167–222. [Google Scholar]

- Witherington, B.E.; Kubilis, P.; Brost, B.; Meylan, A.B. Decreasing Annual Nest Counts in a Globally Important Loggerhead Sea Turtle Population. Ecol. Appl. 2009, 19, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ware, M.; Oliveira de Mello Vieira, L.; Fuentes-Tejada, L.; Silver-Gorges, I.; Fuentes, M.M.P.B. Smaller Size of Nesting Loggerhead Sea Turtles in Northwest Florida. Animals 2026, 16, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010071

Ware M, Oliveira de Mello Vieira L, Fuentes-Tejada L, Silver-Gorges I, Fuentes MMPB. Smaller Size of Nesting Loggerhead Sea Turtles in Northwest Florida. Animals. 2026; 16(1):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010071

Chicago/Turabian StyleWare, Matthew, Luna Oliveira de Mello Vieira, Laura Fuentes-Tejada, Ian Silver-Gorges, and Mariana M. P. B. Fuentes. 2026. "Smaller Size of Nesting Loggerhead Sea Turtles in Northwest Florida" Animals 16, no. 1: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010071

APA StyleWare, M., Oliveira de Mello Vieira, L., Fuentes-Tejada, L., Silver-Gorges, I., & Fuentes, M. M. P. B. (2026). Smaller Size of Nesting Loggerhead Sea Turtles in Northwest Florida. Animals, 16(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010071