Duckweed as a Sustainable Aquafeed: Effects on Growth, Muscle Composition, Antioxidant and Immune Markers in Grass Carp

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish and Diets

2.2. Experimental Set-Up

2.3. Feed Conversion Ratio

2.4. Analysis of Muscle Quality, Physiological and Biochemical Indicators of C. idella

2.5. RNA Extraction, Transcriptomic Analysis, and qRT-PCR Analysis

2.6. Genomics DNA Extraction of Gut Microbes

2.7. Metagenomic Data Analysis

2.8. Analysis of Experimental Data

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Overview of Nutritional Quality of Commercial Feed and S. polyrhiza

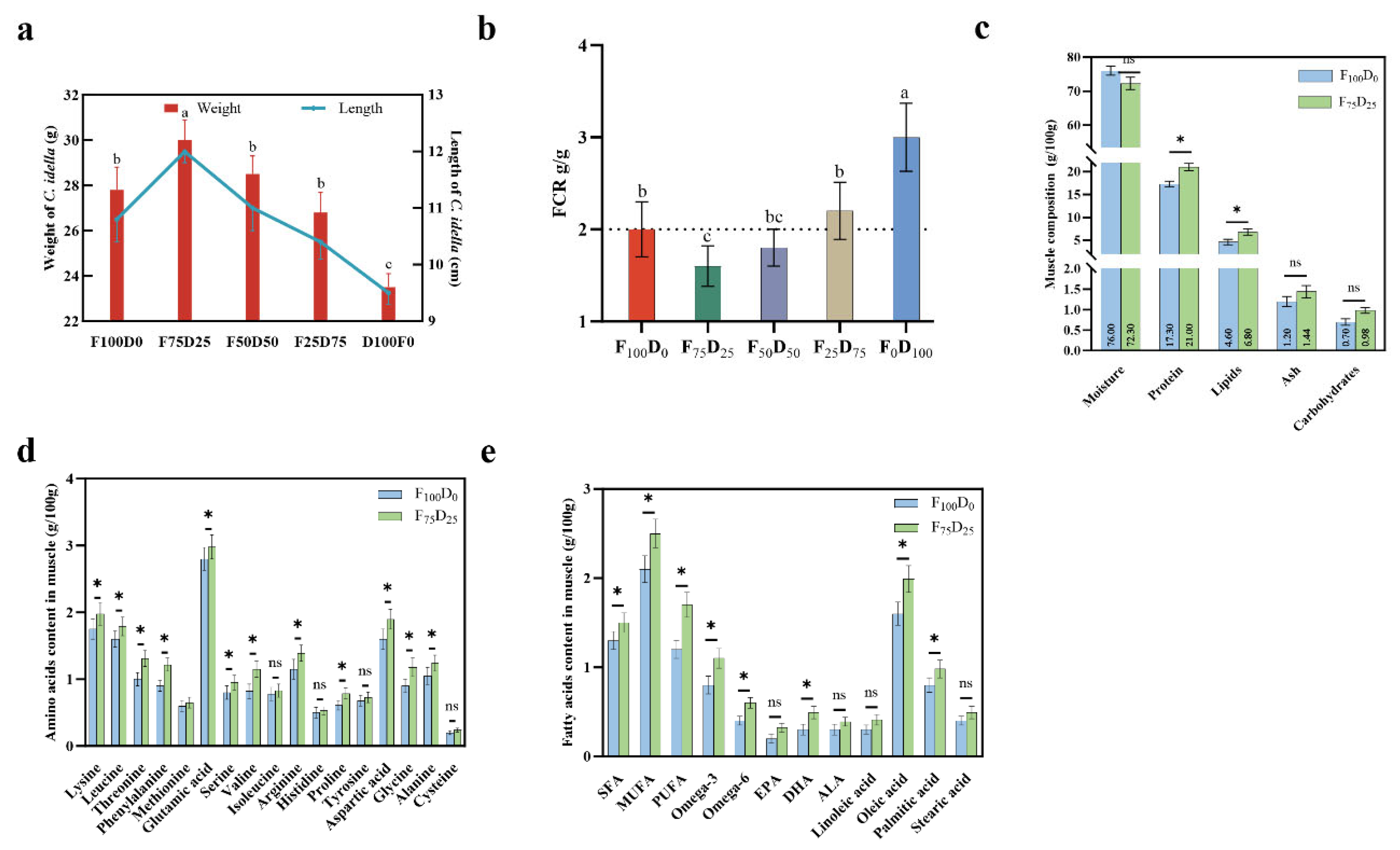

3.2. Growth Performance and Muscle Quality of C. idella with Different S. polyrhiza Proportion

3.3. Biochemical Parameters in the Liver, Muscle, and Blood of C. idella

3.4. Transcriptomic Analysis of C. idella Reveals Enhanced Immune Response, Muscle Quality, and Amino Acid Composition with F75D25 Diet

3.4.1. Immune-Related Genes in the Liver

3.4.2. Genes Related to Muscle Quality in C. idella

3.4.3. Genes Related to Amino Acid Composition in Muscle

3.5. Gut Microbiota Composition and Enhances Functional Capabilities in C. idella with F75D25

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sha, S.; Cheng, M.; Hu, K.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Q. Toxic effects of Pb on Spirodela polyrhiza (L.): Subcellular distribution, chemical forms, morphological and physiological disorders. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 181, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, Z.; Du, X. Physiological responses and transcriptome analysis of Spirodela polyrhiza under red, blue, and white light. Planta 2022, 255, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, N.; Gusain, R.; Suthar, S. Exploring the efficacy of powered guar gum (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba) seeds, duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza), and Indian plum (Ziziphus mauritiana) leaves in urban wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthan, B.; Wang, J.; Welti, R.; Kosma, D.K.; Yu, L.H.; Deo, B.; Khatiwada, S.; Vulavala, V.K.R.; Childs, K.L.; Xu, C.C.; et al. Mechanisms of Spirodela polyrhiza tolerance to FGD wastewater-induced heavy-metal stress: Lipidomics, transcriptomics, and functional validation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, T.; Hanaoka, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Morikawa, M.; Mori, K. Comprehensive evaluation of nitrogen removal rate and biomass, ethanol, and methane production yields by combination of four major duckweeds and three types of wastewater effluent. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.L.; Tan, L.; Guo, L.; Yang, G.L.; Li, Q.; Lai, F.; He, K.Z.; Jin, Y.L.; Du, A.P.; Fang, Y.; et al. Increasing starch productivity of Spirodela polyrhiza by precisely control the spectral composition and nutrients status. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 134, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtlander, T.; Bandy, J.; Rosskothen, D.; Pietsch, C.; Tschudi, F.; Sigrist, M.; Seitz, A.; Leiber, F. Dilution rates of cattle slurry affect ammonia uptake and protein production of duckweed grown in recirculating systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Clark, W.D.; Shrivastav, A.K.; Goswami, R.K.; Tocher, D.R.; Chakrabarti, R. Production potential of greater duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza (L. Schleiden) and its biochemical composition evaluation. Aquaculture 2019, 513, 734419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.G.; Yang, C.; Tang, X.Y.; Zhu, Q.L.; Pan, K.; Cai, D.G.; Hu, Q.C.; Ma, D.W. Carbon and energy fixation of great duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza growing in swine wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 15804–15811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Kalkar, S.; Tinker-Kulberg, R.; Ignatova, T.; Josephs, E.A. The “Duckweed Dip”: Aquatic Spirodela polyrhiza Plants Can Efficiently Uptake Dissolved, DNA-Wrapped Carbon Nanotubes from Their Environment for Transient Gene Expression. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 13, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremikael, M.T.; Ranasinghe, A.; Hosseini, P.S.; Laboan, B.; Sonneveld, E.; Pipan, M.; Oni, F.E.; Montemurro, F.; Höfte, M.; Sleutel, S.; et al. How do novel and conventional agri-food wastes, co-products and by-products improve soil functions and soil quality? Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, I.; Seo, J.; Jung, M.; Kim, Y.; Yim, N.; Bae, K. Vitexin, Orientin and Other Flavonoids from Spirodela polyrhiza Inhibit Adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 Cells. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, C.S.; Lee, M.Y.; Shin, I.S.; Lee, J.A.; Ha, H.; Shin, H.K. Spirodela polyrhiza (L.) Sch ethanolic extract inhibits LPS-induced inflammation in RAW264.7 cells. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2012, 34, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Nam, Y.R.; Kim, E.J.; Nam, J.H.; Kim, W.K. Spirodela polyrhiza and its Chemical Constituent Vitexin Exert Anti-Allergic Effect via ORAI1 Channel Inhibition. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 1243–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowinski, E.E.; Gilbert, S.; Lam, E.; Carpita, N.C. Linkage structure of cell-wall polysaccharides from three duckweed species. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 223, 115119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, S.; Lyu, J.H.; Park, S.; Park, Y.C.; Kim, H. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Spirodela polyrhiza (L.) SCHLEID. Extract on Contact Dermatitis in Mice-Its Active Compounds and Molecular Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minich, J.J.; Michael, T.P. A review of using duckweed (Lemnaceae) in fish feeds. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1212–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltko, R.; Majewska, M.P.; Fraczek, N.; Kowalik, B. Evaluation of the biochemical composition of the greater duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza (L. Schleiden). J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2024, 33, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Kumar, D.; Soni, V. Copper and mercury induced oxidative stresses and antioxidant responses of Spirodela polyrhiza (L.) Schleid. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2020, 23, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Liu, H.; Venkateshan, K.; Yan, S.; Cheng, J.; Sun, X.S.; Wang, D. Functional, physiochemical, and rheological properties of duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) protein. Trans. ASABE 2011, 54, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.W.; Shen, Y.T.; Zheng, Y.; Smith, G.; Sun, X.; Wang, D.H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.H. Duckweed (Lemnaceae) for potentially nutritious human food: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 3620–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.L.; Jiang, Y.J.; Li, F.F.; Yang, Y.R.; Lu, Q.Q.; Zhang, T.L.; Hu, D.; Xu, Q.S. Investigation of subcellular distribution, physiological, and biochemical changes in Spirodela polyrhiza as a function of cadmium exposure. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 142, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.A.; Sultana, N.; Huque, K.S.; Huque, Q.M.E. Manure based duckweed production in shallow sink: Effect of genera on biomass and nutrient yield of duckweed under the same nutritional and management conditions. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 13, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtlander, T.; Tschudi, F.; Seitz, A.; Sigrist, M.; Refardt, D.; Leiber, F. Partial Replacement of Fishmeal with Duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) in Feed for Two Carnivorous Fish Species, Eurasian Perch (Perca fluviatilis) and Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac. Res. 2023, 2023, 6680943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, T.; Han, P.R.; Miao, M.S.; Inc, D.E.P. Influence of Duckweed Decoction Used Externally on Delayed Type Hypersensitivity and Pruritus Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering Applications (CSEA), Sanya, China, 26–27 December 2015; pp. 551–557. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, R.; Weeks, R.; Huang, Q.R.; Dai, W.J.; Cao, Y.; Liu, G.; Guo, Y.J.; Chistyakov, V.A.; Ermakov, A.M.; Rudoy, D.; et al. Fermented Duckweed as a Potential Feed Additive with Poultry Beneficial Bacilli Probiotics. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Sharma, J.; Goswami, R.K.; Shrivastav, A.K.; Tocher, D.R.; Kumar, N.; Chakrabarti, R. Freshwater Macrophytes: A Potential Source of Minerals and Fatty Acids for Fish, Poultry, and Livestock. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 869425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Xie, C. Biology and Ecology of Grass Carp in China: A Review and Synthesis. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2020, 40, 1379–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, A.m.; Tan, H.; Li, M.; Geng, C.; Wang, S.; Zhao, R.; Qin, Q.; Luo, K.; Xu, J.; et al. The comparative studies on growth rate and disease resistance between improved grass carp and common grass carp. Aquaculture 2022, 560, 738476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB5009.3-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Moisture Content in Foods. Chinese Standard Publisher: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB5009.4-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Ash in Foods. Chinese Standard Publisher: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 5009.9-2023; National Food Safety standard—Determination of Starch in Foods. Chinese Standard Publisher: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Xiong, Q.; Feng, J.; Li, S.T.; Zhang, G.Y.; Qiao, Z.X.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, T.; Ge, F.; et al. Integrated Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis of the Global Response of Synechococcus to High Light Stress. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2015, 14, 1038–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, K.V.; Henske, J.K.; Theodorou, M.K.; O’Malley, M.A. Robust and effective methodologies for cryopreservation and DNA extraction from anaerobic gut fungi. Anaerobe 2016, 38, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.H.; Lomsadze, A.; Borodovsky, M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agusti, A.; Moya-Pérez, A.; Campillo, I.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Cerrudo, V.; Perez-Villalba, A.; Sanz, Y. Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum CECT 7765 Ameliorates Neuroendocrine Alterations Associated with an Exaggerated Stress Response and Anhedonia in Obese Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 5337–5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.M.; Niu, B.F.; Zhu, Z.W.; Wu, S.T.; Li, W.Z. CD-HIT: Accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3150–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huson, D.H.; Auch, A.F.; Qi, J.; Schuster, S.C. MEGAN analysis of metagenomic data. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357-U354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Yekutieli, D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1165–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.A.; Boguñá, M.; Sagués, F. Uncovering the hidden geometry behind metabolic networks. Mol. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtey, A.P.; Lamberti, P.W.; Prato, D.P. Jensen-Shannon divergence as a measure of distinguishability between mixed quantum states. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 72, 052310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, P.; Grochowicz, J.; Lusiak, P.; Zukiewicz-Sobczak, W. Development of Alternative Protein Sources in Terms of a Sustainable System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhang, K.J.; Khan, F.A.; Pandupuspitasari, N.S.; Guan, K.F.; Sun, F.; Huang, C.J. A comprehensive review on signaling attributes of serine and serine metabolism in health and disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.Y.; Bazer, F.W.; Davis, T.A.; Jaeger, L.A.; Johnson, G.A.; Kim, S.W.; Knabe, D.A.; Meininger, C.J.; Spencer, T.E.; Yin, Y.L. Important roles for the arginine family of amino acids in swine nutrition and production. Livest. Sci. 2007, 112, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagawany, M.; Elnesr, S.S.; Farag, M.R.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Taha, A.E.; Tiwari, R.; Yatoo, M.I.; Bhatt, P.; Khurana, S.K.; et al. Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids in Poultry Nutrition: Effect on Production Performance and Health. Animals 2019, 9, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002, 56, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, V.S.; Braakhuis, A.J.; Hopkins, W.G. Effect of Flavonoids on Upper Respiratory Tract Infections and Immune Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.L.; Li, G.H.; Li, Y.R.; Wu, X.Y.; Ren, D.M.; Lou, H.X.; Wang, X.N.; Shen, T. Lignan and flavonoid support the prevention of cinnamon against oxidative stress related diseases. Phytomedicine 2019, 53, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.M.; Ren, Z.Y.; Zhao, L.; Chen, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, D.X.; Mao, X.J.; Cao, G.T.; Zhao, Z.L.; Yang, H.S. Unique roles in health promotion of dietary flavonoids through gut microbiota regulation: Current understanding and future perspectives. Food Chem. 2023, 399, 133959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, M.; Qu, M.; Kumar, V. Effect of oil source on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, fatty acid composition and fillet quality of juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquac. Nutr. 2020, 26, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, R.; Stambolie, J.; Bell, R.J.L.R.f.R.D. Duckweed-a potential high-protein feed resource for domestic animals and fish. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 1995, 7, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Saurabh, S.; Sahoo, P.K. Lysozyme: An important defence molecule of fish innate immune system. Aquac. Res. 2008, 39, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-Y.; Zhang, X.-C.; Jia, R.-Y. Toll-Like Receptors and RIG-I-Like Receptors Play Important Roles in Resisting Flavivirus. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 6106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, H.; Coelho, A.R.; Wan, J.; Mehta, H.H.; Yen, K.; Huang, A.; Zempo, H.; Fuku, N.; Maeda, S.; Oliveira, P.J.; et al. MOTS-c reduces myostatin and muscle atrophy signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Endoc. Metab. 2021, 320, E680–E690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Goraksha-Hicks, P.; Li, L.; Neufeld, T.P.; Guan, K.-L. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafie, S.K.; Al-Mulla, F.; Abubaker, J. mTOR: Its Critical Role in Metabolic Diseases, Cancer, and the Aging Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.J.; Qiang, J.; Li, Q.J.; Nie, Z.J.; Gao, J.C.; Sun, Y.; Xu, G.C. Multi-kingdom microbiota and functions changes associated with culture mode in genetically improved farmed tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 974398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.H.; Yu, H.Y.; Yan, Y.L.; Ping, S.Z.; Lu, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, M.; Lin, M. Benzoate Catabolite Repression of the Phenol Degradation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus PHEA-2. Curr. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.H.; Yan, Y.L.; Zhang, W.; Chen, M.; Lu, W.; Ping, S.Z.; Lin, M. Comparative analysis of the complete genome of an Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain adapted to a phenol-polluted environment. Res. Microbiol. 2012, 163, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S.D.; Ivanova, I.V.; Popov, I.; Weeks, R.; Chikindas, M.L. Bacillus spore-forming probiotics: Benefits with concerns? Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 48, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomartire, S.; Marques, J.C.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. An Overview to the Health Benefits of Seaweeds Consumption. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatlin, D.M.; Barrows, F.T.; Brown, P.; Dabrowski, K.; Gaylord, T.G.; Hardy, R.W.; Herman, E.; Hu, G.S.; Krogdahl, Å.; Nelson, R.; et al. Expanding the utilization of sustainable plant products in aquafeeds: A review. Aquac. Res. 2007, 38, 551–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venold, F.F.; Penn, M.H.; Krogdahl, A.; Overturf, K. Severity of soybean meal induced distal intestinal inflammation, enterocyte proliferation rate, and fatty acid binding protein (Fabp2) level differ between strains of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 2012, 364, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category of Nutrients | Nutrient | Content (g/100 g Dry Weight) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Feed | S. polyrhiza | ||

| Basic Components | Protein | 28.00 | 35.43 |

| Starch | 30.48 | 14.50 | |

| Total Lipids | 4.45 | 5.87 | |

| Ash | 9.56 | 7.74 | |

| Amino Acid Composition | Lysine | 1.82 | 2.13 |

| Leucine | 2.05 | 2.68 | |

| Threonine | 1.24 | 1.61 | |

| Phenylalanine | 1.31 | 1.72 | |

| Methionine | 0.60 | 0.46 | |

| Glutamic Acid | 4.08 | 6.68 | |

| Serine | 1.25 | 1.89 | |

| Isoleucine | 1.18 | 1.78 | |

| Arginine | 1.67 | 2.35 | |

| Histidine | 0.70 | 0.74 | |

| Proline | 1.12 | 1.58 | |

| Tyrosine | 1.05 | 1.46 | |

| Glycine | 1.53 | 2.56 | |

| Alanine | 2.03 | 2.94 | |

| Cysteine | 0.40 | 0.49 | |

| Fatty Acid Composition | SFA | 2.06 | 1.44 |

| MUFA | 1.51 | 1.08 | |

| PUFA | 1.53 | 3.48 | |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | 1.47 | 2.88 | |

| Omega-6 Fatty Acids | 0.81 | 0.60 | |

| α-Linolenic Acid | 0.35 | 2.64 | |

| Linoleic Acid | 0.80 | 0.60 | |

| Oleic Acid | 1.03 | 0.96 | |

| Palmitic Acid | 1.09 | 1.20 | |

| Stearic Acid | 0.55 | 0.24 | |

| Flavonoid Compounds (mg/100 g) | Total Flavonoids | - | 158.43 |

| Quercetin | - | 28.50 | |

| Rutin | - | 24.38 | |

| Chlorogenic Acid | - | 13.25 | |

| Catechin | - | 31.23 | |

| Apigenin | - | 10.45 | |

| Kaempferol | - | 14.74 | |

| Fisetin | - | 5.65 | |

| Component (g/kg DM) | F100D0 | F75D25 | F50D50 | F25D75 | F0D100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial feed | 1000.0 | 720.0 | 480.0 | 240.0 | 0.0 |

| Duckweed meal | 0.0 | 240.00 | 480.0 | 720.0 | 940.0 |

| Added fish meal | 0.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 |

| Added wheat starch | 0.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 20.0 | 30.0 |

| Added vegetable oil | 0.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 30.0 |

| Total (g/kg DM) | 1000.0 | 1000.0 | 1000.0 | 1000.0 | 1000.0 |

| Proximate composition (% DM) | |||||

| Crude protein | 28.0 | 28.8 | 29.5 | 30.2 | 30.8 |

| Crude lipid | 4.50 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.8 |

| Starch | 30.5 | 28.5 | 26.5 | 24.5 | 22.5 |

| Ash | 9.6 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 8.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, Y.; Hu, Z.; Yang, X.; An, Y.; Lu, Y. Duckweed as a Sustainable Aquafeed: Effects on Growth, Muscle Composition, Antioxidant and Immune Markers in Grass Carp. Animals 2026, 16, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010053

Song Y, Hu Z, Yang X, An Y, Lu Y. Duckweed as a Sustainable Aquafeed: Effects on Growth, Muscle Composition, Antioxidant and Immune Markers in Grass Carp. Animals. 2026; 16(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yingjie, Zhangli Hu, Xuewei Yang, Yuxing An, and Yinglin Lu. 2026. "Duckweed as a Sustainable Aquafeed: Effects on Growth, Muscle Composition, Antioxidant and Immune Markers in Grass Carp" Animals 16, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010053

APA StyleSong, Y., Hu, Z., Yang, X., An, Y., & Lu, Y. (2026). Duckweed as a Sustainable Aquafeed: Effects on Growth, Muscle Composition, Antioxidant and Immune Markers in Grass Carp. Animals, 16(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010053