Coexistence of Humans and Hamadryas Baboons in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia—Emotional, Social, and Financial Aspects

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Selected Interviews

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondents’ Characteristics

3.2. Responses According to the Four Dimensions

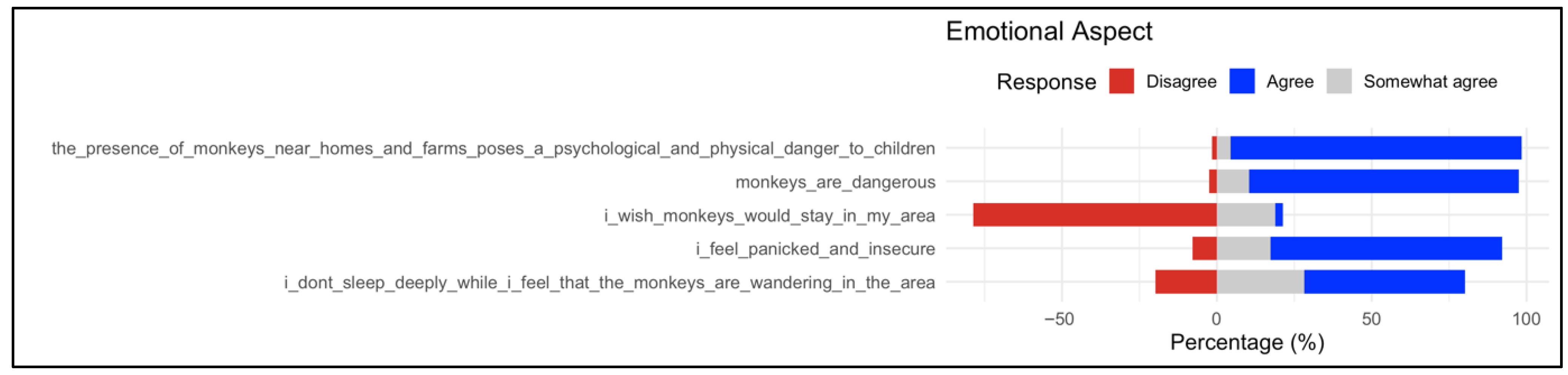

3.2.1. Emotional Aspect

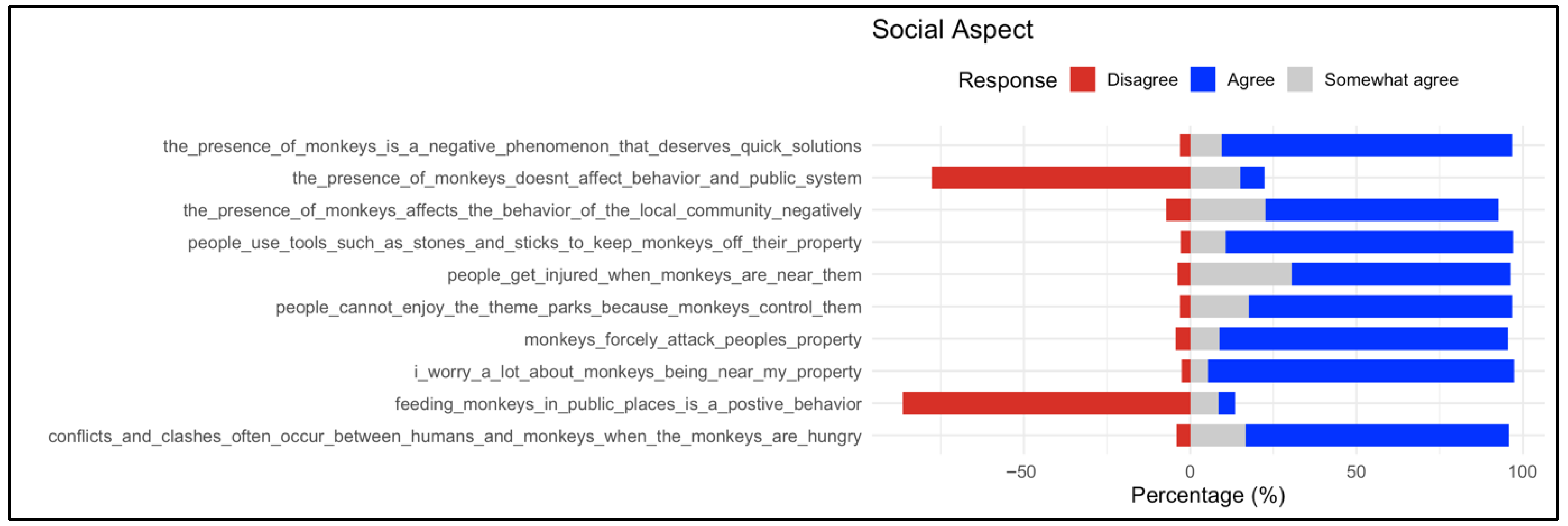

3.2.2. Social Aspect

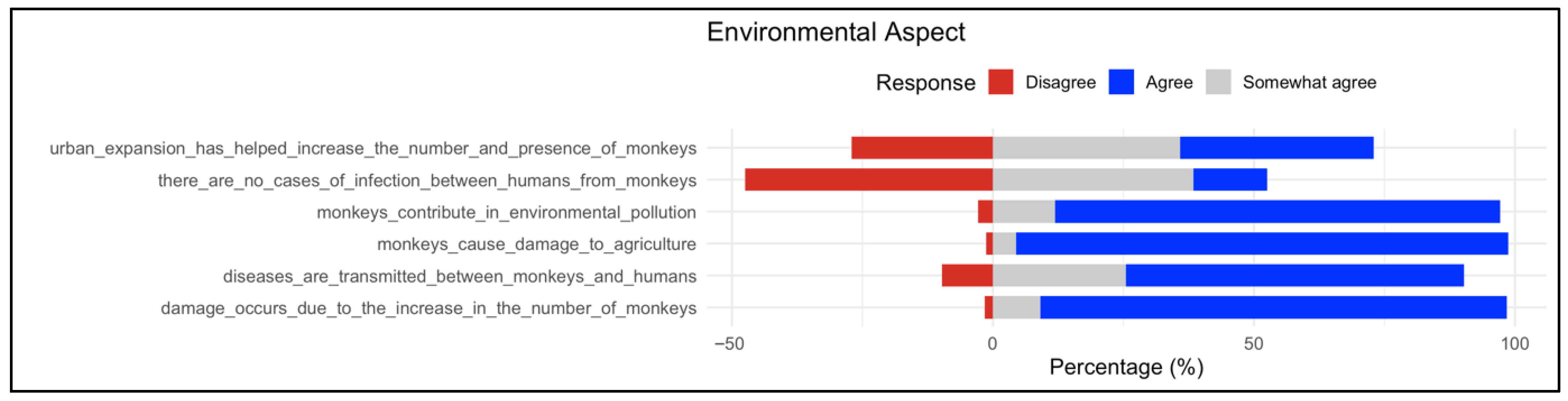

3.2.3. Environmental Aspect

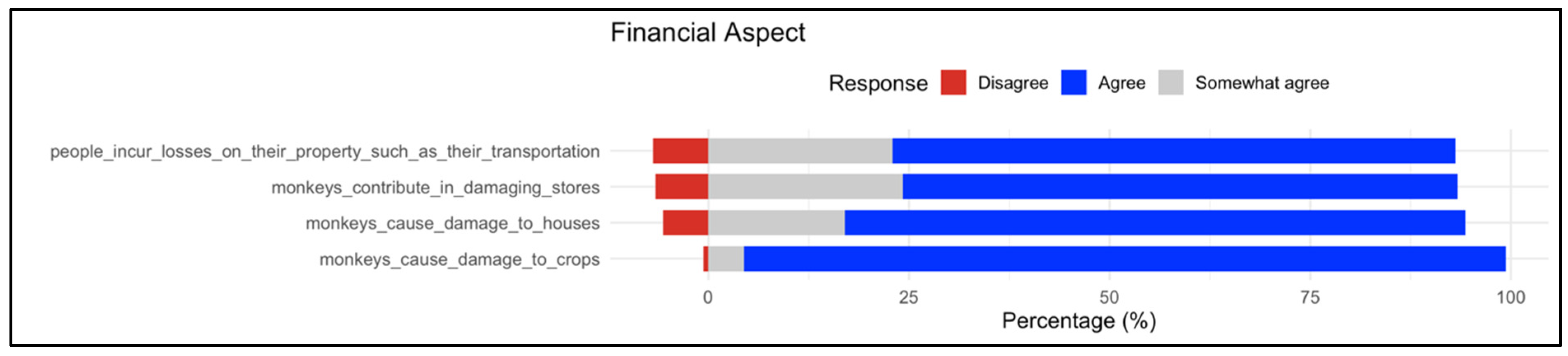

3.2.4. Financial Aspect

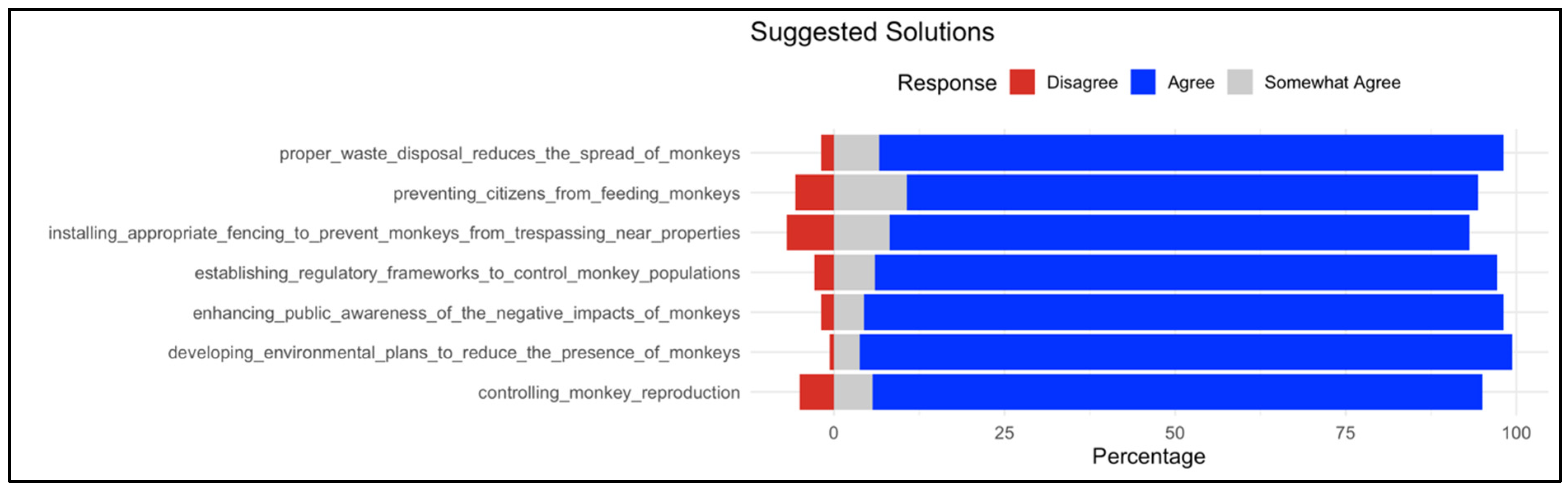

3.2.5. Suggested Solutions to Control the Presence of Baboons

3.3. Selected Interviews

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cowlishaw, G.; Dunbar, R.I.M. Primate Conservation Biology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN World Park Congress (WPC). Preventing & Mitigating Human–Wildlife Conflicts; WPC Recommendation 20; IUCN: Durban, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsbury, C.D.; White, P.C.L. Human–wildlife interactions in urban areas: A review of conflicts, benefits and opportunities. Wildl. Res. 2016, 42, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; McQuinn, B.; Macdonald, D.W. Levels of conflict over wildlife: Understanding and addressing the right problem. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkin, R.D.; Seto, K.C.; McDonald, R.I.; Jetz, W. Biodiversity impacts and conservation implications of urban land expansion projected to 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117297119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilthuizen, M. Darwin Comes to Town: How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution; Picador: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Else, J.G. Nonhuman primates as pests. In Primate Responses to Environmental Change; Box, H.O., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strum, S.C. Prospects for management of primate pests. Rev. Écol. 1994, 49, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strum, S.C. The development of primate raiding: Implications for management and conservation. Int. J. Primatol. 2010, 31, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.M. Conflict of interest between people and baboons: Crop raiding in Uganda. Int. J. Primatol. 2000, 21, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.M. Crop foraging, crop losses, and crop raiding. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2018, 47, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton-Treves, L. Farming the forest edge: Vulnerable places and people around Kibale National Park, Uganda. Geogr. Rev. 1997, 87, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagoro-Rugunda, G. Crop raiding around Lake Mburo National Park. Afr. J. Ecol. 2004, 42, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsvanga, C.A.T.; Jimu, L.; Mupangwa, J.F.; Zinner, D. Susceptibility of pine stands to bark stripping by chacma Papio ursinus baboons in the Eastern Highlands of Zimbabwe. Curr. Zool. 2009, 55, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, L.J. Human-Primate Conflict: An Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Wildlife Crop Raiding on Commercial Crop Farms in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2016. Available online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11872/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Kifle, Z.; Bekele, A. Human–hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas) conflict in the Wonchit Valley, South Wollo, Ethiopia. Afr. J. Ecol. 2021, 59, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleta, M.; Tekalign, W. Crop loss and damage by primate species in Southwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Ecol. 2023, 2023, 8332493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, N.U. Crop and livestock depredation caused by wild animals in protected areas: The case of Sariska Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, India. Environ. Conserv. 1998, 25, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, S.; Garber, P.A.; Somasundaram, D.; Katuwal, H.B.; Ren, B.; Huang, C.; Li, M. Factors affecting the crop raiding behavior of wild rhesus macaques in Nepal: Implications for wildlife management. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudran, R.; Cabral de Mel, S.J.; Sumanapala, A.; De Mel, R.K.; Mahindarathna, K.K.T. An ethnoprimatological approach to mitigating Sri Lanka’s human–monkey conflicts. Primate Conserv. 2021, 35, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Priston, N.E.C.; McLennan, M.R. Managing humans, managing macaques: Human–macaque conflict in Asia and Africa. In The Macaque Connection: Cooperation and Conflict Between Humans and Macaques; Radhakrishna, S., Huffman, M.A., Sinha, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 225–249. [Google Scholar]

- Biquand, S.; Boug, A.; Biquand-Guyot, V.; Gautier, J.P. Management of commensal baboons in Saudi Arabia. Rev. Écol. 1994, 49, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, T.S.; O’Riain, M.J. Monkey management: Using spatial ecology to understand the extent and severity of human–baboon conflict in the Cape Peninsula, South Africa. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlmann, G.; O’Riain, M.J.; Fürtbauer, I.; King, A.J. Behavioral causes, ecological consequences, and management challenges associated with wildlife foraging in human-modified landscapes. BioScience 2021, 71, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, G.; Alzahrani, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.; Alzahrani, W.; Zinner, D. Potential hotspots of hamadryas baboon–human conflict in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia. Diversity 2023, 15, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazué, F.; Guerbois, C.; Fritz, H.; Rebout, N.; Petit, O. Less bins, less baboons: Reducing access to anthropogenic food effectively decreases the urban foraging behavior of a troop of chacma baboons (Papio hamadryas ursinus) in a peri-urban area. Primates 2023, 64, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. Block, push or pull? Three responses to monkey crop-raiding in Japan. In Understanding Conflicts About Wildlife: A Biosocial Approach; Hill, C.M., Webber, A.D., Priston, N.E.C., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, S.J.; Prasad, T.; Deeyagoda, T.P.; Weerakkody, S.N.; Nadarajah, A.; Rudran, R. Investigating Sri Lanka’s human–monkey conflict and developing a strategy to mitigate the problem. J. Threat. Taxa 2018, 10, 11391–11398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittus, W.P.J.; Gunathilake, S.; Felder, M. Assessing public perceptions and solutions to human–monkey conflict from 50 years in Sri Lanka. Folia Primatol. 2019, 90, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebsworth, P.A.; Radhakrishna, S. The costs and benefits of coexistence: What determines people’s willingness to live near nonhuman primates? Am. J. Primatol. 2021, 83, e23310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimullah, K.; Widdig, A.; Sah, S.; Amici, F. Understanding potential conflicts between human and non-human primates: A large-scale survey in Malaysia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 1249–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poornima, A.M.N.S.; Weerasekara, W.M.L.S.; Vinobaba, M.; Karunarathna, K.A.N.K. Community-level awareness and attitudes towards human–monkey conflict in Polonnaruwa district, Sri Lanka. Primates 2022, 63, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D.L. The Mammals of Arabia, Vol. I. Insectivora, Chiroptera, Primates; Ernest Benn: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D.L. The large mammals in Arabia. Oryx 1968, 9, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT). Statistical Yearbook of 2021; Saudi General Authority for Statistics: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/annual-report (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Dunford, C.; Faure, J.; Ross, M.; Spalton, J.; Drouilly, M.; Pryce-Fitchen, K.; Mann, G. Searching for spots: A comprehensive survey for the Arabian leopard Panthera pardus nimr in Saudi Arabia. Oryx 2024, 58, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HABITAT City Prosperity Index: Al-Baha. United Nations Saudi Arabia. 2019. Available online: https://saudiarabia.un.org/en/40072-city-prosperity-index-albaha (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Mahmoud, S.H.; Alazba, A.A. Land cover change dynamics mapping and predictions using EO data and a GIS-cellular automata model: The case of Al-Baha region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, M.; Alzandi, A.A.; Shrahily, R.; Mobarak, B. Land use land cover change analysis for urban growth prediction using Landsat satellite data and Markov Chain Model for Al-Baha Region Saudi Arabia. Forests 2022, 13, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasher, A.K.A. Zoonotic parasite infections of the Arabian sacred baboon Papio hamadryas arabicus Thomas in Asir Province, Saudi Arabia. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1988, 63, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandour, A.M.; Zahid, N.Z.; Banaja, A.A.; Kamal, K.B.; Bouq, A.I. Zoonotic intestinal parasites of hamadryas baboons Papio hamadryas in the western and northern regions of Saudi Arabia. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1995, 98, 431–439. [Google Scholar]

- Zahed, N.Z.; Ghandour, A.M.; Banaja, A.A.; Banerjee, R.K.; Dehlawi, M.S. Hamadryas baboons Papio hamadryas as maintenance hosts of Schistosoma mansoni in Saudi Arabia. Trop. Med. Int. Health 1996, 1, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqumber, M.A. Association between Papio hamadryas populations and human gastrointestinal infectious diseases in southwestern Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2014, 34, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarinmoye, A.O.; Olugasa, B.O.; Niphuis, H.; Herwijnen, R.V.; Verschoor, E.; Boug, A.; Ishola, O.O.; Buitendijk, H.; Fagrouch, Z.; Al-Hezaimi, K. Serological evidence of coronavirus infections in native hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas hamadryas) of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasem, S.; Hussein, R.; Al-Doweriej, A.; Qasim, I.; Abu-Obeida, A.; Almulhim, I.; Alfarhan, H.; Hodhod, A.A.; Abel-latif, M.; Hashim, O.; et al. Rabies among animals in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climate and Average Weather Year Round in Al Bahah, Saudi Arabia. WeatherSpark. Available online: https://weatherspark.com/y/101924/Average-Weather-in-Al-Bahah-Saudi-Arabia-Year-Round (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Saudi Census. General Authority of Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Marisa, L.; Chimwe, M.; Zhou, K.; Chinofunga, A.T.; Njini, B.; Mugadza, L.; Nkomo, P.; Dirwayi, T.P. Baboon–human conflict (BHC), an emerging urban crisis faced by residents in Redcliff Municipality, Zimbabwe. Glob. Sci. J. 2022, 10, 886–894. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay, L.J.; Hill, R.A. Field guarding as a crop protection method: Preliminary implications for improving field guarding. Hum.-Wildl. Interact. 2020, 14, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.M.; Wallace, G.E. Crop protection and conflict mitigation: Reducing the costs of living alongside non-human primates. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 2569–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distefano, E. Human-Wildlife Conflict Worldwide: Collection of Case Studies, Analysis of Management Strategies and Good Practices; FAO Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development Initiative: Rome, Italy, 2005; Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents (accessed on 30 November 2025).

| Variable | Category | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 94 (30%) |

| Male | 224 (70%) | |

| Age | <30 | 89 (28%) |

| 30–39 | 81 (25%) | |

| 40–49 | 84 (27%) | |

| >50 | 64 (20%) | |

| Education | None | 1 (0.3%) |

| Primary | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Intermediate | 4 (1.3%) | |

| Secondary | 53 (16.7%) | |

| High education | 259 (81.4%) | |

| Employment | Unemployed | 100 (31%) |

| Government employee | 164 (51%) | |

| Private sector employee | 38 (12%) | |

| Farmer | 8 (3%) | |

| Seller | 8 (3%) | |

| Housing geography | Big city | 66 (21%) |

| Medium city | 49 (15%) | |

| Small town | 53 (17%) | |

| Village | 150 (47%) | |

| Damaged property | Farm | 153 (48%) |

| Residence | 95 (30%) | |

| Store | 2 (0.6%) | |

| Others | 68 (21.4%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alghamdi, S.; Zinner, D.; AlMalki, M.; Salamah, S.; Al-Ghamdi, S.; Althubyani, M.; Al-Ghamdi, A.; Alzahrani, W.; Alzahrani, A.; Al-Ghamdi, G. Coexistence of Humans and Hamadryas Baboons in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia—Emotional, Social, and Financial Aspects. Animals 2026, 16, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010047

Alghamdi S, Zinner D, AlMalki M, Salamah S, Al-Ghamdi S, Althubyani M, Al-Ghamdi A, Alzahrani W, Alzahrani A, Al-Ghamdi G. Coexistence of Humans and Hamadryas Baboons in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia—Emotional, Social, and Financial Aspects. Animals. 2026; 16(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlghamdi, Salihah, Dietmar Zinner, Mansour AlMalki, Seham Salamah, Saleh Al-Ghamdi, Mohammed Althubyani, Abdullah Al-Ghamdi, Wael Alzahrani, Abdulaziz Alzahrani, and Ghanem Al-Ghamdi. 2026. "Coexistence of Humans and Hamadryas Baboons in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia—Emotional, Social, and Financial Aspects" Animals 16, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010047

APA StyleAlghamdi, S., Zinner, D., AlMalki, M., Salamah, S., Al-Ghamdi, S., Althubyani, M., Al-Ghamdi, A., Alzahrani, W., Alzahrani, A., & Al-Ghamdi, G. (2026). Coexistence of Humans and Hamadryas Baboons in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia—Emotional, Social, and Financial Aspects. Animals, 16(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010047