Changes in Fish Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Diversity and Their Driving Factors in a Reservoir in the Karst Basin of Southwest China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

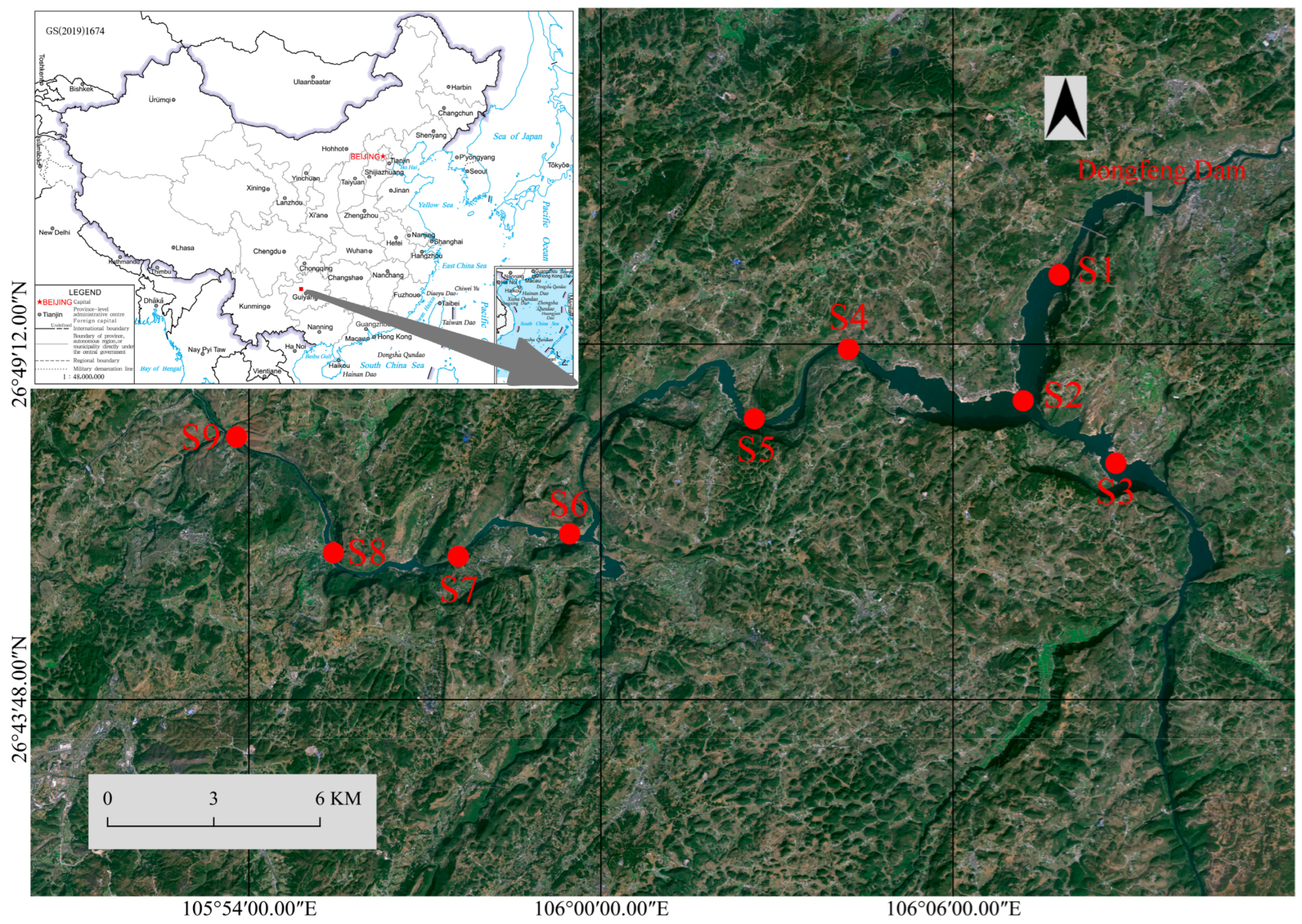

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Survey

2.3. Taxonomic Diversity

2.4. Phylogenetic Diversity

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

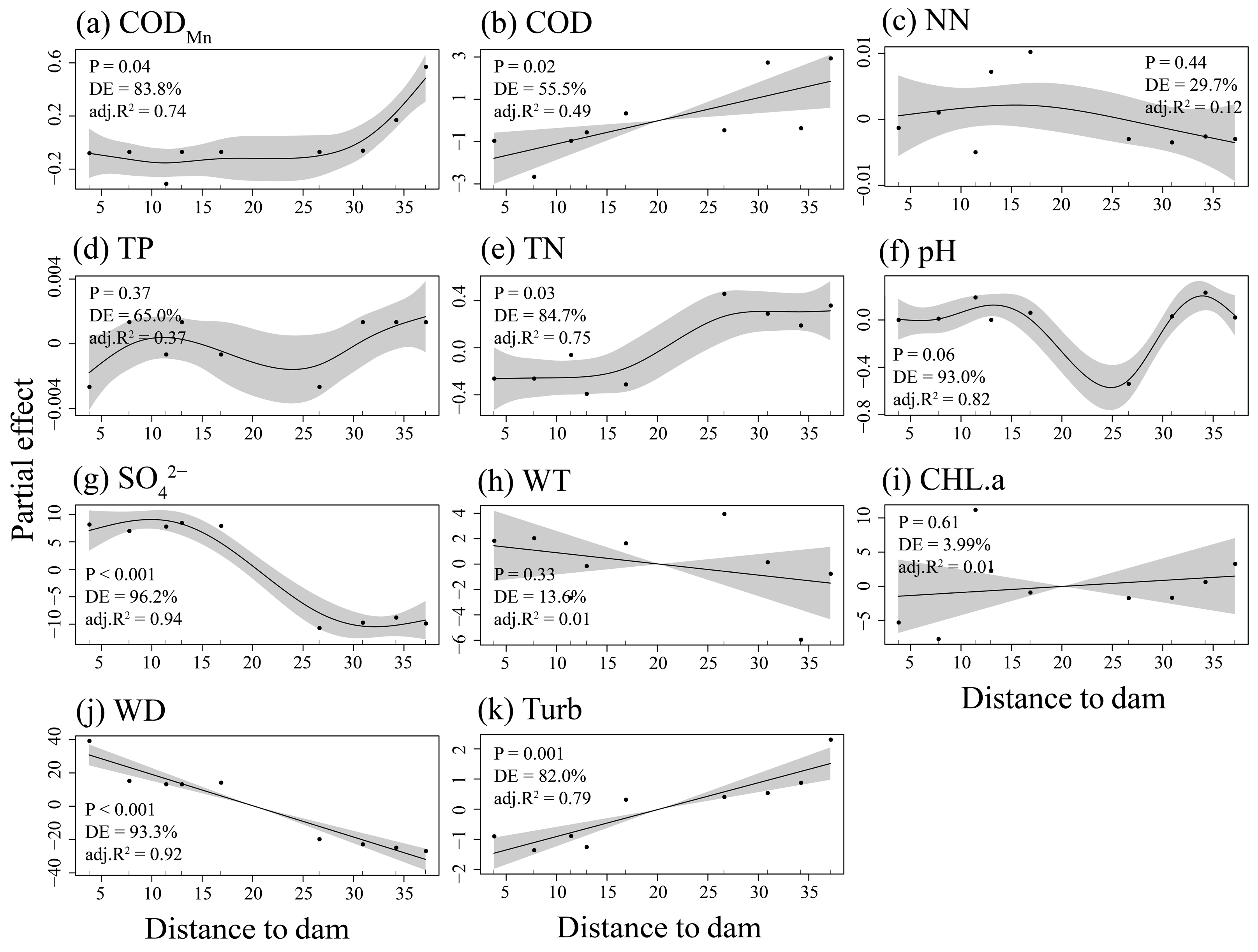

3.1. The Distribution Patterns of Environmental Characteristics of the Dongfeng Reservoir

3.2. Fish Composition in the Dongfeng Reservoir

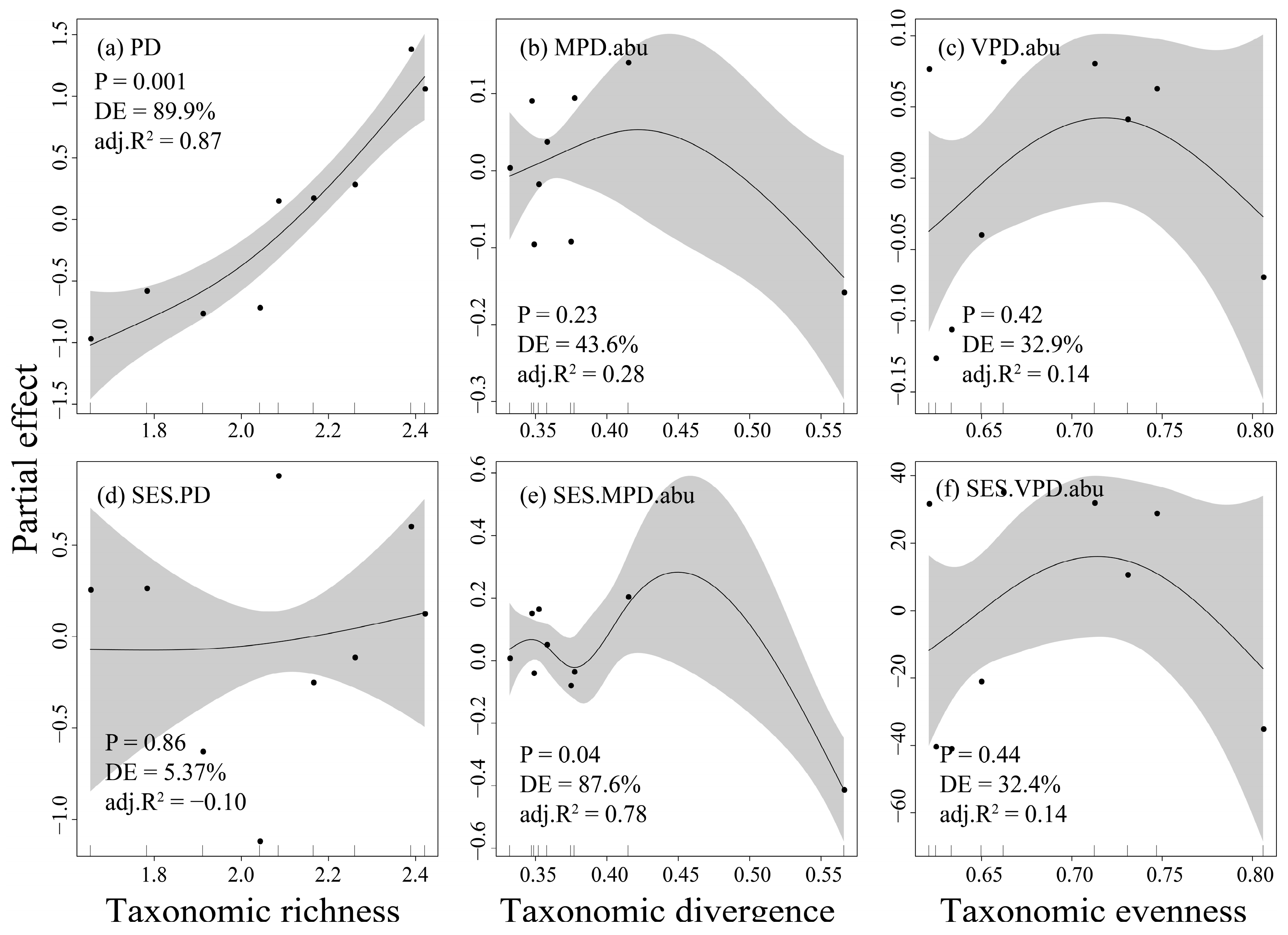

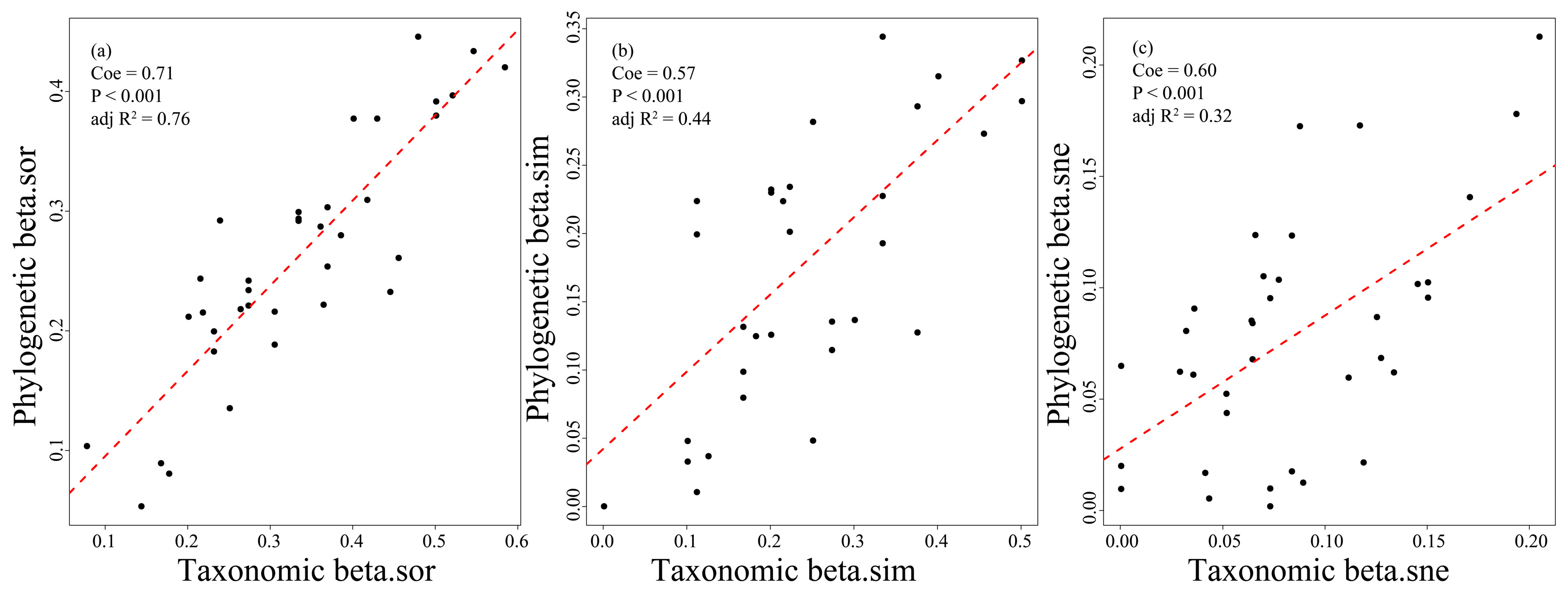

3.3. The Relationships Between Fish Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Diversity in the Dongfeng Reservoir

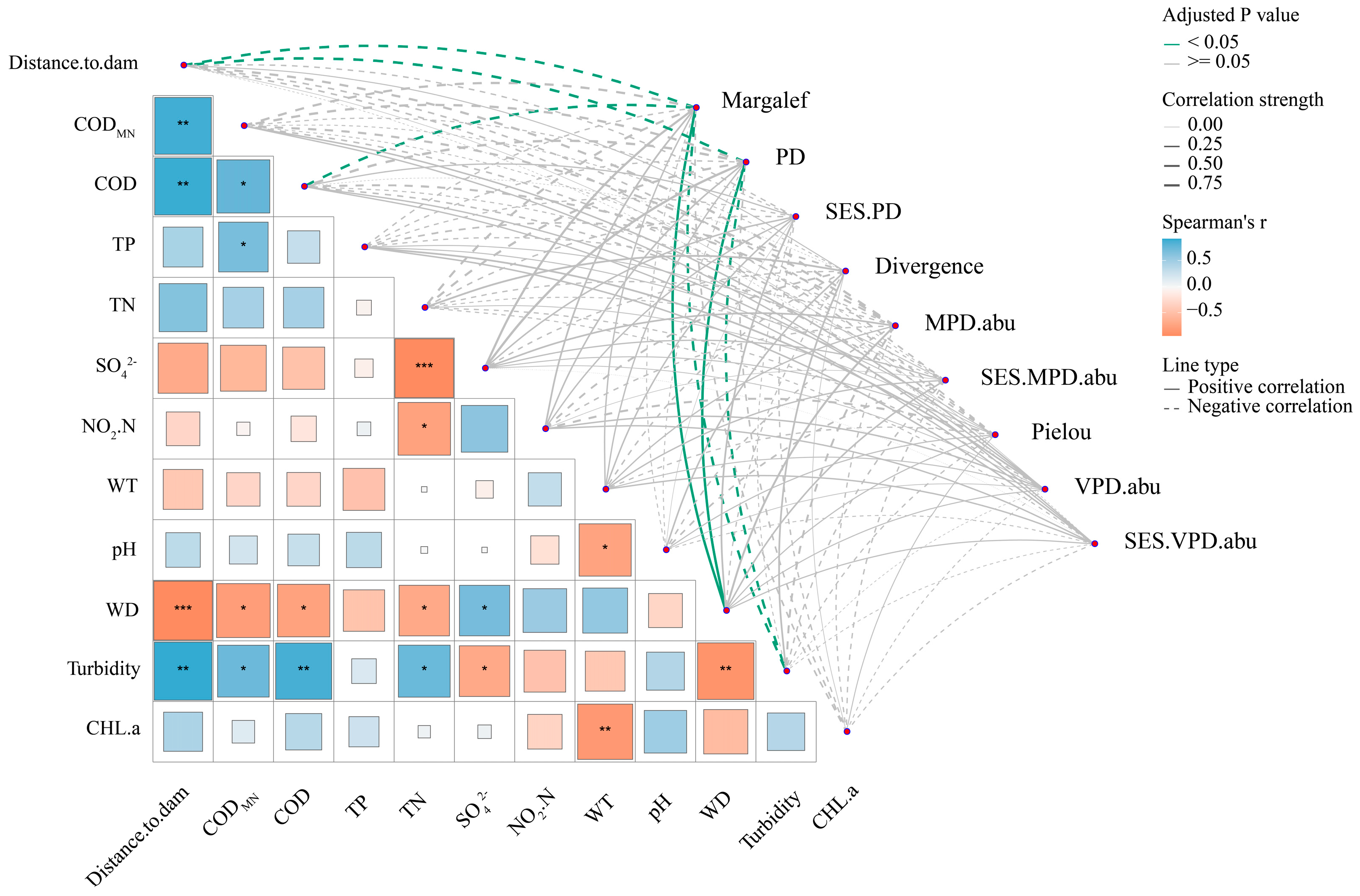

3.4. Drivers of Fish Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Diversity in the Dongfeng Reservoir

4. Discussion

4.1. The Homogeneous Environmental Characteristics in the Dongfeng Reservoir

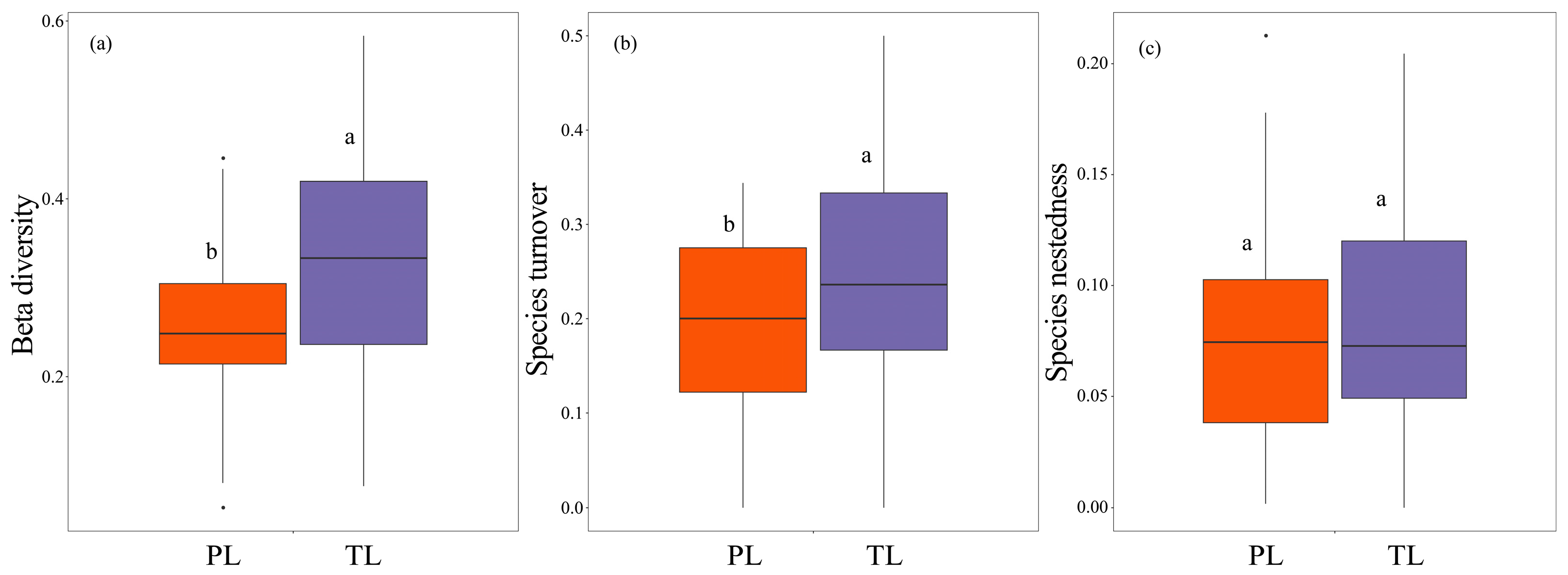

4.2. The Significant Differences in Fish Taxonomic and Phylogenetic β-Diversity with High Turnover Pattern

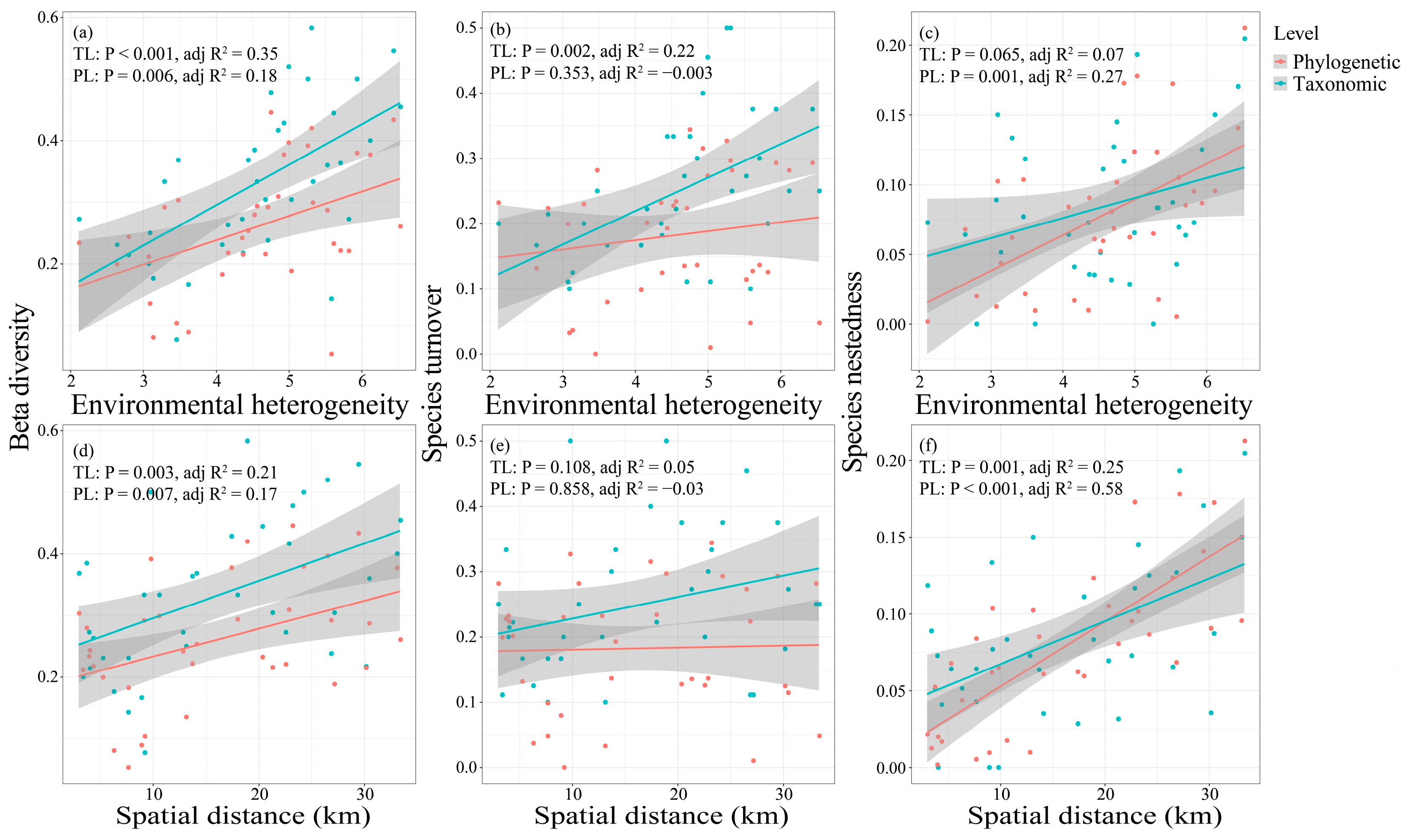

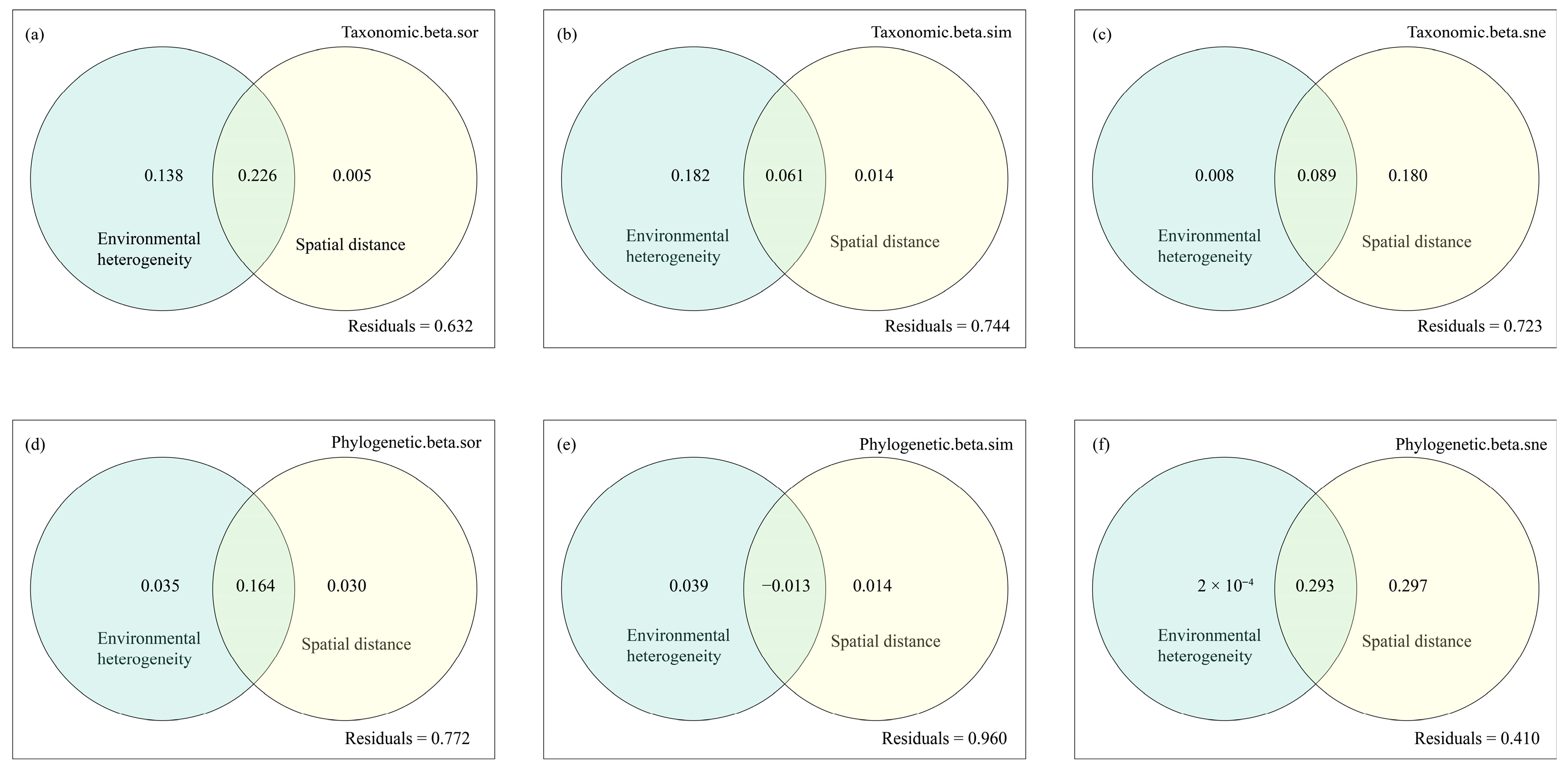

4.3. Environmental Heterogeneity Mainly Drives Taxonomic and Phylogenetic β-Diversity and Turnover Processes, While Spatial Distance Dominates Nestedness Processes

4.4. Fish Conservation Measures for the Dongfeng Reservoir

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| βtax | Taxonomic β-diversity |

| PD | Faith’s phylogenetic diversity |

| MPD.abu | Abundance-based mean pairwise distances |

| VPD.abu | Abundance-based variation of pairwise distances |

| SES | Standardized effect size |

| Obs.phy.alpha | Observed phylogenetic α-diversity |

| Mean.rand.phy.alpha | Mean of the randomized phylogenetic α-diversity |

| SD.rand.phy.alpha | Standard deviation of the randomized phylogenetic α-diversity |

| beta.dev | Beta deviation |

| βphy | Phylogenetic β-diversity |

| IRI | Relative importance index |

| Fi | Occurrence frequency |

| Ni | Proportion of individuals |

| Wi | Proportion of biomass |

| GAMs | Generalized additive models |

References

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington, A.H.; Gessner, M.O.; Kawabata, Z.I.; Knowler, D.J.; Lévéque, C.; Naiman, R.J.; Prieur-Richard, A.H.; Soto, D.; Stiassny, M.L.J.; et al. Freshwater biodiversity: Importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. 2006, 81, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.J.; Carlson, A.K.; Creed, I.F.; Eliason, E.J.; Gell, P.A.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Kidd, K.A.; MacCormack, T.J.; Olden, J.D.; Ormerod, S.J.; et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickner, D.; Opperman, J.J.; Abell, B.; Acreman, M.; Arthington, A.H.; Bunn, S.E.; Cooke, S.J.; Dalton, J.; Darwall, W.; Edwards, G.; et al. Bending the curve of global freshwater biodiversity loss: An emergency recovery plan. BioScience 2020, 70, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBD. First Draft of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework; CBD/WG2020/3/3; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon, D.; Strayer, D.L. Bending the curve of global freshwater biodiversity loss: What are the prospects? Biol. Rev. 2025, 100, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götzenberger, L.; de Bello, F.; Bråthen, K.A.; Davison, J.; Dubuis, A.; Guisan, A.; Leps, J.; Lindborg, R.; Moora, M.; Pärtel, M.; et al. Ecological assembly rules in plant communities-approaches, patterns and prospects. Biol. Rev. 2012, 87, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socolar, J.B.; Gilroy, J.J.; Kunin, W.E.; Edwards, D.P. How should beta-diversity inform biodiversity conservation? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, A.S.; Isbell, F.; Seidl, R. β-diversity, community assembly, and ecosystem functioning. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo-Madrid, R.; González-Suárez, M.; Rosvall, M.; Rueda, M.; Revilla, E.; Carrete, M.; Tella, J.L.; Astigarraga, J.; Calatayud, J. A general rule on the organization of biodiversity in Earth’s biogeographical regions. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 9, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.H. Vegetation of the Siskiyou mountains, Oregon and California. Ecol. Monogr. 1960, 30, 279–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, T.A.; Cooper, M.J.; Reisinger, L.S.; Reisinger, A.J.; Uzarski, D.G. Water depth and lake-wide water level fluctuation influence on α-and β-diversity of coastal wetland fish communities. J. Gt. Lakes Res. 2018, 44, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Cáceres, M. Beta diversity as the variance of community data: Dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, R.E.; He, F.L. Region effects influence local tree species diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianuca, A.T.; Declerck, S.A.J.; Lemmens, P.; De Meester, L. Effects of dispersal and environmental heterogeneity on the replacement and nestedness components of β-diversity. Ecology 2017, 98, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez, O.; Pavanelli, C.S. Environmental heterogeneity and dispersal limitation explain different aspects of β-diversity in Neotropical fish assemblages. Freshw. Biol. 2019, 64, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.T.; Magoulick, D.D. Fish beta diversity associated with hydrologic and anthropogenic disturbance gradients in contrasting stream flow regimes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 173825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, D.P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 1992, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.H.; Fine, P.V.A. Phylogenetic beta diversity: Linking ecological and evolutionary processes across space in time. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, D.S.; Cadotte, M.W.; MacDonald, A.A.M.; Marushia, R.G.; Mirotchnick, N. Phylogenetic diversity and the functioning of ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, C.M.; Cadotte, M.W.; Carvalho, S.B.; Davies, T.J.; Ferrier, S.; Fritz, S.A.; Grenyer, R.; Helmus, M.R.; Jin, L.S.; Mooers, A.O.; et al. A guide to phylogenetic metrics for conservation, community ecology and macroecology. Biol. Rev. 2017, 92, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, T.K.; Grenouillet, G.; Villéger, S. Species contribute differently to the taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic alpha and beta diversity of freshwater fish communities. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.C.; Lv, Y.Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.C.; Peng, W.Q.; Qu, X.D. Understanding the relative roles of local environmental, geo-climatic and spatial factors for taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic β-diversity of stream fishes in a large basin, Northeast China. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leprieur, F.; Albouy, C.; Bortoli, J.; Cowman, P.F.; Bellwood, D.R.; Mouillot, D. Quantifying phylogenetic beta diversity: Distinguishing between ‘true’ turnover of lineages and phylogenetic diversity gradients. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Cao, Y.; Chu, C.J.; Li, D.J.; Sandel, B.; Wang, X.L.; Jin, Y.; Soininen, J. Taxonomic and phylogenetic β-diversity of freshwater fish assemblages in relationship to geographical and climatic determinants in North America. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbell, S. The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Leibold, M.A.; Holyoak, M.; Mouquet, N.; Amarasekare, P.; Chase, J.M.; Hoopes, M.F.; Holt, R.D.; Shurin, J.B.; Law, R.; Tilman, D.; et al. The metacommunity concept: A framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecol. Lett. 2004, 7, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, J.; Melo, A.S.; Bini, L.M. Reconceptualising the beta diversity-environmental heterogeneity relationship in running water systems. Freshw. Biol. 2015, 60, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soininen, J.; McDonald, R.; Hillebrand, H. The distance decay of similarity in ecological communities. Ecography 2007, 30, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Jin, Y.; Leprieur, F.; Wang, X.L.; Deng, T. Geographic patterns and environmental correlates of taxonomic and phylogenetic beta diversity for large-scale angiosperm assemblages in China. Ecography 2020, 43, 1706–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soininen, J.; Heino, J.; Wang, J.J. A meta-analysis of nestedness and turnover components of beta diversity across organisms and ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganassin, M.J.M.; Muñoz-Mas, R.; de Oliveira, F.J.M.; Muniz, C.M.; dos Santos, N.C.L.; García-Berthou, E.; Gomes, L.C. Effects of reservoir cascades on diversity, distribution, and abundance of fish assemblages in three Neotropical basins. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timpe, K.; Kaplan, D. The changing hydrology of a dammed Amazon. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.W.; Li, Q.Y.; Lin, Y.Q.; Zhang, J.Y.; Xia, J.; Ni, J.R.; Cooke, S.J.; Best, J.; He, S.F.; Feng, T.; et al. River Damming Impacts on Fish Habitat and Associated Conservation Measures. Rev. Geophys. 2023, 61, e2023RG000819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loures, R.C.; Pompeu, P.S. Temporal changes in fish diversity in lotic and lentic environments along a reservoir cascade. Freshw. Biol. 2019, 64, 1806–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ding, C.Z.; Ding, L.Y.; Chen, L.Q.; Hu, J.M.; Tao, J.; Jiang, X.M. Large-scale cascaded dam constructions drive taxonomic and phylogenetic differentiation of fish fauna in the Lancang River, China. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 2019, 29, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.H.; Wen, X.X.; Wang, H.J.; Wu, Y.Z.; Yi, Y.J. Research on the driving factors of fish community structure and phylogenetic diversity in the Three Gorges Dam based on environmental DNA. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, A.; Peláez, Ó.; Velho, L.F.M.; de Carvalho, P.; Rodrigues, L.C. A Run-of-River Mega-Dam in the Largest Amazon Tributary Changed the Diversity Pattern of Planktonic Communities and Caused the Loss of Species. Freshw. Biol. 2025, 70, e70025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.Q. Biogeochemical Process of Nitrogen/Phosphorus and Modelling of Water Environment in Cascade Reservoirs, Southwest China; Tianjin University: Tianjin, China, 2023. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, T.; He, L.; Deng, W. Analysis on bryophyte flora in fluctuating belt of Dongfeng Reservoir area in Wujiang River of Guizhou Province. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2017, 26, 97–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Lin, L.; Wang, L.L.; Zhang, Y.P.; Kang, B. Prioritizing the multifaceted community and species uniqueness for the conservation of lacustrine fishes in the largest subtropical floodplain, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 363, 121301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olinger, C.T.; Hart, J.L.; Howeth, J.G. Functional trait sorting increases over succession in metacommunity mosaics of fish assemblages. Oecologia 2021, 196, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. The Fishes of Guizhou Province; Guizhou People’s Press: Guiyang, China, 1989. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Fishes of Guizhou; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, T.C.; Ma, K.H.; Chao, A. iNEXT: iNterpolation and EXTrapolation for Species Diversity. R Package Version 3. 2022. Available online: http://chao.stat.nthu.edu.tw/wordpress/software-download/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- HJ 493-2009; Water Quality. Technical Regulation of the Preservation and Handling of Samples. China Environmental Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Baselga, A.; Orme, D.; Villeger, S.; De Bortoli, J.; Leprieur, F.; Logez, M.; Martinez-Santalla, S.; Martin-Devasa, R.; Gomez-Rodriguez, C.; Crujeiras, R. Betapart: Partitioning Beta Diversity into Turnover and Nestedness Components. R Package Version 1.6. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=betapart (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, W.P.; Maddison, D.R. Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis, Version 3.81. 2023. Available online: http://www.mesquiteproject.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, V.; Longueville, J.E.; Gascuel, O. SMS: Smart model selection in PhyML. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 2422–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, N.G. Functional and Phylogenetic Ecology in R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. ape 5.0: An environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembel, S.W.; Cowan, P.D.; Helmus, M.R.; Cornwell, W.K.; Morlon, H.; Ackerly, D.D.; Blomberg, S.P.; Webb, C.O. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearse, W.D.; Cadotte, M.W.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Ives, A.R.; Tucker, C.M.; Walker, S.C.; Helmus, M.R. pez: Phylogenetics for the environmental sciences. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2888–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, F.P.; Villalobos, F.; Melo, A.S.; Diniz-Filho, J.A.F.; Loyola, R.; Rangel, T.F.; Cianciaruso, M.V. Geographical patterns of phylogenetic beta-diversity components in terrestrial mammals. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhu, F.Y.; Liu, S.P.; Duan, X.B.; Chen, D.Q. Seasonal variations of fish community structure of Lake Hanfeng in Three Gorges Reservoir region. J. Lake Sci. 2017, 29, 439–447. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.S.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.G.; Mao, L.F.; Zhang, W.H. glmm.hp: An R package for computing individual effect of predictors in generalized linear mixed models. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.F.; Chen, W.M.; Cai, Q.M. Survey, observation and analysis of lake ecology. In Standard Methods for Observation and Analysis in Chinese Ecosystem Research Network, Series V; Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 1999. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, T.; Syvitski, J.P. Turbidity currents generated at river mouths during exceptional discharges to the world oceans. J. Geol. 1995, 103, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.L.; Cheng, L.L.; Li, C.; Zheng, L.G. A hydrochemical and multi-isotopic study of groundwater sulfate origin and contribution in the coal mining area. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2022, 248, 114286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eme, D.; Anderson, M.J.; Myers, E.M.V.; Roberts, C.D.; Liggins, L. Phylogenetic measures reveal eco-evolutionary drivers of biodiversity along a depth gradient. Ecography 2020, 43, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, C.; Bacaro, G.; Caccianiga, M.; Cerabolini, B.E.; Pavoine, S. A new method for quantifying the phylogenetic redundancy of biological communities. Oecologia 2018, 186, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pool, T.K.; Olden, J.D. Taxonomic and functional homogenization of an endemic desert fish fauna. Divers. Distrib. 2012, 18, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Zhou, T.T.; Heino, J.; Castro, D.M.P.; Cui, Y.D.; Li, Z.F.; Wang, W.M.; Chen, Y.S.; Xie, Z.C. Land conversion induced by urbanization leads to taxonomic and functional homogenization of a river macroinvertebrate metacommunity. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 153940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, N.G. Phylogenetic Beta Diversity Metrics, Trait Evolution and Inferring the Functional Beta Diversity of Communities. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahel, F.J. Homogenization of freshwater faunas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002, 33, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D.; Comte, L.; Giam, X. Biotic Homogenisation. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Comte, L.; Olden, J.D. Fish dispersal in flowing waters: A synthesis of movement- and genetic-based studies. Fish Fish. 2018, 19, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacone Santos, A.B.; Albieri, R.J.; Araújo, F.G. Seasonal response of fish assemblages to habitat fragmentation caused by an impoundment in a Neotropical river. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2013, 96, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellend, M.; Srivastava, D.S.; Anderson, K.M.; Brown, C.D.; Jankowski, J.E.; Kleynhans, E.J.; Kraft, N.J.B.; Letaw, A.D.; Macdonald, A.A.M.; Maclean, J.E.; et al. Assessing the relative importance of neutral stochasticity in ecological communities. Oikos 2014, 123, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.j.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Deng, J.M.; Qin, B.Q.; Yin, H.B.; Wang, X.L.; Gong, Z.J.; Heino, J. Metacommunity ecology meets bioassessment: Assessing spatio-temporal variation in multiple facets of macroinvertebrate diversity in human-influenced large lakes. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 103, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.A.; Peres-Neto, P.R.; Olden, J.D. What controls who is where in freshwater fish communities—The roles of biotic, abiotic, and spatial factors. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2001, 58, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracheil, B.M.; McIntyre, P.B.; Lyons, J.D. Enhancing conservation of large-river biodiversity by accounting for tributaries. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T. Space-for-time substitution as an alternative to long-term studies. In Long-Term Studies in Ecology: Approaches and Alternatives; Likens, G.E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.R.; Zhu, Q.; Li, Y.R.; Kang, B.; Chu, L.; Yan, Y.Z. Effects of low-head dams on fish assemblages in subtropical streams: Context dependence on species category and data type. River Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Tang, W.J.; Heino, J.; Jiang, X.M. Effects of dam construction and fish invasion on the species, functional and phylogenetic diversity of fish assemblages in the Yellow River Basin. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order/Family/Species | OF | RA | RB | IRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cypriniformes | ||||

| Xenocyprididae | ||||

| Opsariichthys bidens | 88.89 | 2.80 | 2.43 | 464.75 |

| Hemiculter leucisculus | 100 | 6.01 | 2.63 | 863.69 |

| Culter alburnus | 11.11 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 2.01 |

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix | 11.11 | 0.08 | 9.48 | 106.27 |

| Gobionidae | ||||

| Pseudorasbora parva | 55.56 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 34.84 |

| Abbottina rivularis | 22.22 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 4.01 |

| Acheilognathidae | ||||

| Rhodeus sinensis | 66.67 | 3.21 | 0.27 | 231.82 |

| Rhodeus ocellatus | 11.11 | 0.49 | 0.08 | 6.36 |

| Cyprinidae | ||||

| Spinibarbus sinensis | 22.22 | 0.49 | 9.20 | 215.35 |

| Onychostoma yunnanense | 11.11 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 3.34 |

| Onychostoma simum | 22.22 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 13.24 |

| Cyprinus carpio | 77.78 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 168.02 |

| Carassius auratus | 100 | 22.55 | 14.69 | 3724.24 |

| Pseudogyrinocheilus prochilus | 55.56 | 4.77 | 8.22 | 721.86 |

| Discogobio yunnanensis | 33.33 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 10.14 |

| Cobitidae | ||||

| Misgurnus dabryanus | 11.11 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 4.60 |

| Siluriformes | ||||

| Siluridae | ||||

| Silurus asotus | 44.44 | 0.33 | 3.77 | 182.36 |

| Silurus meridionalis | 11.11 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.65 |

| Bagridae | ||||

| Tachysurus sinensis | 33.33 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 67.05 |

| Tachysurus crassilabris | 55.56 | 1.81 | 1.40 | 178.35 |

| Gobiiformes | ||||

| Gobiidae | ||||

| Rhinogobius similis | 66.67 | 1.15 | 0.03 | 78.83 |

| Cichliformes | ||||

| Cichlidae | ||||

| Coptodon zillii | 100 | 19.34 | 17.77 | 3711.27 |

| Centrarchiformes | ||||

| Centrarchidae | ||||

| Lepomis cyanellus | 100 | 32.92 | 27.14 | 6006.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Yao, W.; Ma, H.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Ouyang, L. Changes in Fish Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Diversity and Their Driving Factors in a Reservoir in the Karst Basin of Southwest China. Animals 2026, 16, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010145

Qiao J, Liu Y, Yao W, Ma H, Yu L, Zhao Q, Ouyang L. Changes in Fish Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Diversity and Their Driving Factors in a Reservoir in the Karst Basin of Southwest China. Animals. 2026; 16(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiao, Jialing, Yang Liu, Weiwei Yao, Hong Ma, Liang Yu, Qin Zhao, and Lijian Ouyang. 2026. "Changes in Fish Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Diversity and Their Driving Factors in a Reservoir in the Karst Basin of Southwest China" Animals 16, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010145

APA StyleQiao, J., Liu, Y., Yao, W., Ma, H., Yu, L., Zhao, Q., & Ouyang, L. (2026). Changes in Fish Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Diversity and Their Driving Factors in a Reservoir in the Karst Basin of Southwest China. Animals, 16(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010145