Understanding the Preferences of Genetic Tools and Extension Services for the Northern Australia Beef Industry

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Analysis

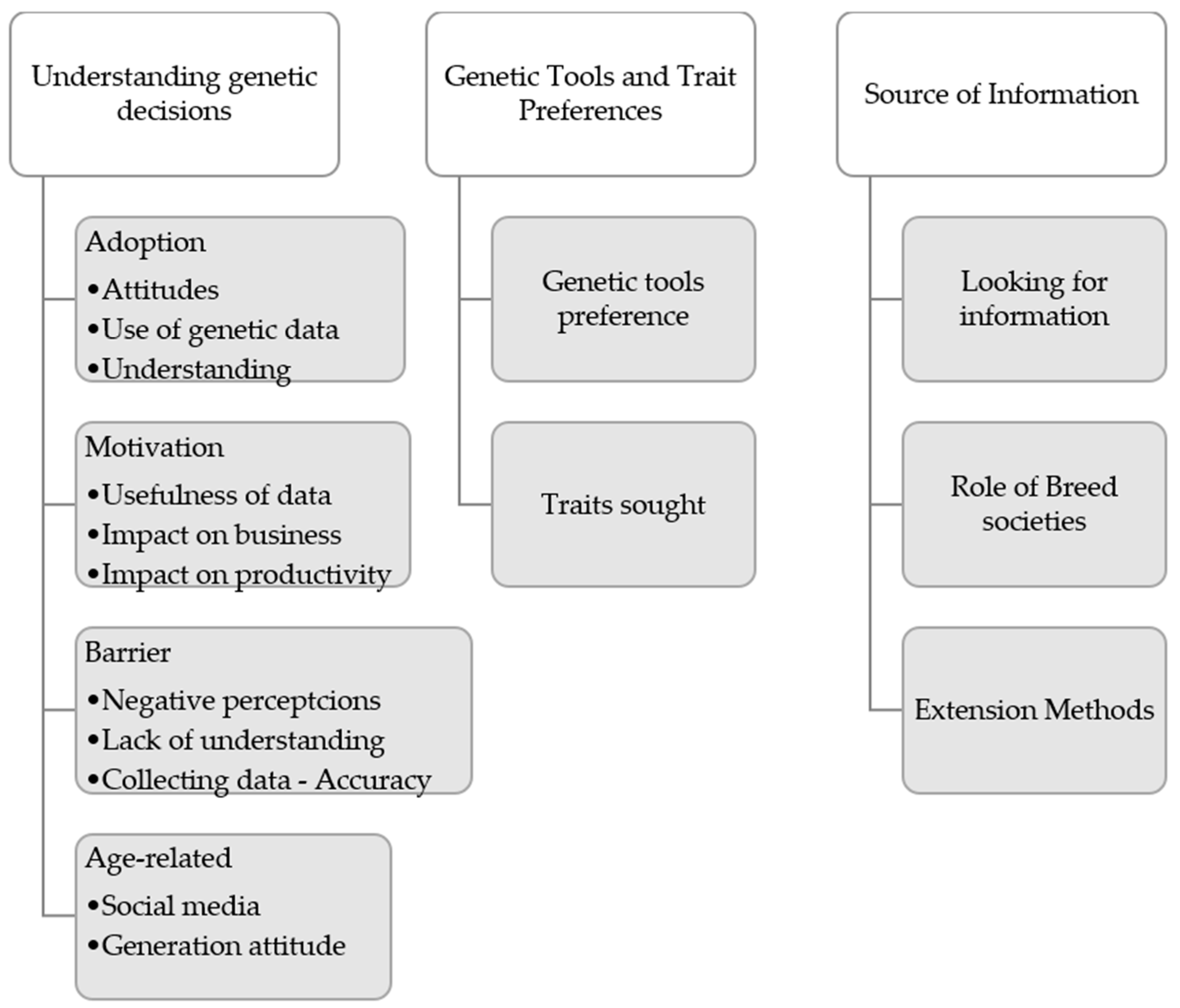

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Understanding Genetic Decisions

3.1.1. Current Level of Adoption

3.1.2. Motivations for Adoption of Genetic Tools

3.1.3. Barriers to Adoption of Genetic Tools

3.1.4. Generational Attitudes

3.2. Genetic Tools and Traits Preferences

3.2.1. Genetic Tools Preferences

3.2.2. Traits Sought by Beef Producers

3.3. Genetic Information Resources

3.3.1. Looking for Genetic Information

3.3.2. The Role of Breed Societies

3.3.3. Extension Methods

4. Theoretical Framework

5. Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Macintosh, A.; Simpson, A.; Chilcot, C.; Ash, A.; Sigrid, L.; Stokes, C.; Ed, C.; Collins, K.; Pavey, C.; Berglas, R.; et al. Northern Australia Beef Situation Analysis. A Report to the Cooperative Research Centre for Developing Northern Australia; CRCNA: Townsville, QLD, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cottle, D.; Kahn, L. Beef Cattle Production and Trade; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2014; p. 583. [Google Scholar]

- Lavender, S.; Cowan, T.; Hawcroft, M.; Wheeler, M.; Jarvis, C.; Cobon, D.; Nguyen, H.; Hudson, D.; Sharmila, S.; Marshall, A.; et al. The Northern Australia Climate Program: Overview and Selected Highlights. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 103, E2492–E2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.; Sangster, N. Research, development and adoption for the north Australian beef cattle breeding industry: An analysis of needs and gaps. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2023, 63, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North Australia Beef Research Council (NABRC) (2022) North Australia Beef Research Council (NABRC) Producer Identified RD&A Priorities for 2023 2024 RDA Priorities. Available online: https://www.nabrc.com.au/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Jakku, E.; Farbotko, C.; Curnock, M.; Watson, I. Insights on Technology Adoption and Innovation Among Northern Australian Beef Producers; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Synthesis and the Road Ahead. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 328–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devitt, S.K. Cognitive factors that affect the adoption of autonomous agriculture. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannell, D.J.; Vanclay, F. Changing Land Management: Adoption of New Practices by Rural Landholders; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Munguia, O.M.d.O.; Pannell, D.J.; Llewellyn, R.; Stahlmann-Brown, P. Adoption pathway analysis: Representing the dynamics and diversity of adoption for agricultural practices. Agric. Agric. Syst. 2021, 191, 103173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Hyland, P.; Bosch, O. A Systemic View of Innovation Adoption in the Australian Beef Industry. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2015, 32, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 22, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, E.; Stevenson, M.; Beggs, D.; Mansell, P.; Pryce, J.; Murray, A.; Pyman, M. Herd manager attitudes and intentions regarding the selection of high-fertility EBV sires in Australia. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 4375–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, C.A.; Coleman, G.J.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Campbell, A.J.D.; Doyle, R.E. Positive attitudes, positive outcomes: The relationship between farmer attitudes, management behaviour and sheep welfare. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton-Regester, K.J.; Wright, J.D.; Rabiee, A.R.; Barnes, T.S. Understanding dairy farmer intentions to make improvements to their management practices of foot lesions causing lameness in dairy cows. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019, 171, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski, L.E.; Zarestky, J.; Gonzalez, E. Planning Qualitative Research: Design and Decision Making for New Researchers. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406920967174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saengwong, S.; Thannithi, W.; Intawicha, P.; Porkaew, C. Development of a mobile app for recording and management alert on-farm to supporting beef cattle smallholder farmers. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2021, 17, 697–712. [Google Scholar]

- Halkias, D.; Neubert, M.; Thurman, P.W.; Harkiolakis, N. The Multiple Case Study Design: Methodology and Application for Management Education; Taylor & Francis Group: Milton, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.; Blackman, D. A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnier, S.; Magne, M.; Pailleux, J.; Poupart, S.; Ingrand, S. Management priorities of livestock farmers: A ranking system to support advice. Livest. Sci. 2012, 144, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, Y.; Sow, F.; Govoeyi, B.; Moula, N.; Sissokho, M.M.; Antoine-Moussiaux, N. Stakeholder involvement in cattle-breeding program in developing countries: A Delphi survey. Livest. Sci. 2019, 228, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Khooharo, A.A.; Mirani, Z.; Siddiqui, B.N. Analysis of extension system of Pakistan dairy development company perceived by the field staff. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 6, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, R.; La, N.; Smith, E. Research Report C: The Advisory and Extension System. Prepared for: ‘Stimulating Private Sector Extension in Australian Agriculture to Increase Returns from R&D’; A project of the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR) Rural R&D for profit program; University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Otter.ai. Why Otter.ai. Available online: https://Otter.ai (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- NVivo, Release 1.7.1 (1534); QSR International Pty Ltd.: Doncaster, Australia, 2024.

- Morris, C.; Holloway, L. Genetics and livestock breeding in the UK: Co-constructing technologies and heterogeneous biosocial collectivities. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 33, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.L.; Johnston, D.J.; Grant, T.P. An investigation into potential genetic predictors of birth weight in tropically adapted beef cattle in northern Australia. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2023, 63, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.; Speight, S.; Ross, E.; Dodd, E.; Fordyce, G. Accelerating Genetic Gain for Productivity and Profitability in Northern Beef Cattle with Genomic Technologies; Final Report P.PSH.0833; Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA): Sydney, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ule, A.; Erjavec, K.; Klopčič, M. Influence of dairy farmers’ knowledge on their attitudes towards breeding tools and genomic selection. Animal 2023, 17, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menchon, P.; Manning, J.K.; Swain, D.L.; Cosby, A. Exploration of Extension Research to Promote Genetic Improvement in Cattle Production: Systematic Review. Animals 2024, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Munguia, O.M.d.O.; Llewellyn, R. The Adopters versus the Technology: Which Matters More when Predicting or Explaining Adoption? Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2020, 42, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, B.; Walker, L. MLA Genetics Insights-Finall Report L.GEN.2205; Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA): Sydney, Australia, 2023. Available online: https://www.mla.com.au/contentassets/f0758d90686b48eca21cebbfd2d03000/l.gen.2205---genetics-insights-final-report-public.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Bell, A.; Sangster, N. Needs and Gaps Analysis for NB2; Final Report of Project B.GBP.0055; Meat & Livestock Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- BREEDPLAN—Agricultural Business Research Institute. Understanding EBV Accuracy; BREEDPLAN: Armidale, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://breedplan.une.edu.au/general/understanding-ebv-accuracy/#:~:text=By%20definition%2C%20an%20EBV%20is%20an%20estimate%20of,been%20used%20in%20the%20calculation%20of%20that%20EBV (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Martin-Collado, D.; Díaz, C.; Benito-Ruiz, G.; Ondé, D.; Rubio, A.; Byrne, T.J. Measuring farmers’ attitude towards breeding tools: The Livestock Breeding Attitude Scale. Animal 2021, 15, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitienei, I.; Gillespie, J.; Scaglia, G. Adoption of management practices and breed types by US grass-fed beef producers. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2018, 34, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.; Randhawa, I.L. GEN.1713–Improving the Australian Poll Gene Marker Test [Report]; M. L. A. Limited: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Understanding Extension. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/t0060e/T0060E03.htm#:~:text=Extension%20is%20any%20activity%20that,for%20their%20own%20future%20development (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Nettle, R.; Major, J.; Turner, L.; Harris, J. Selecting methods of agricultural extension to support diverse adoption pathways: A review and case studies. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2024, 64, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Oca Munguia, O.; Pannell, D.J.; Llewellyn, R. Understanding the Adoption of Innovations in Agriculture: A Review of Selected Conceptual Models. Agronomy 2021, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre, Y.H.; Gebru, G.W.; Gebre, K.T. Adoption of artificial insemination technology and its intensity of use in Eastern Tigray National Regional State of Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2022, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Collado, D.; Byrne, T.; Amer, P.; Santos, B.; Axford, M.; Pryce, J. Analyzing the heterogeneity of farmers’ preferences for improvements in dairy cow traits using farmer typologies. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 4148–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricultural Business Research Institute. Barriers to Adoption of Genetic Improvement Technologies in Norther Australia Beef Herds; Final Report. B.NBP.0753; Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA): Sydney, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, G. The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Menchon, P.; Cosby, A.; Swain, D.L.; Manning, J.K. Understanding the Preferences of Genetic Tools and Extension Services for the Northern Australia Beef Industry. Animals 2026, 16, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010132

Menchon P, Cosby A, Swain DL, Manning JK. Understanding the Preferences of Genetic Tools and Extension Services for the Northern Australia Beef Industry. Animals. 2026; 16(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenchon, Patricia, Amy Cosby, Dave L. Swain, and Jaime K. Manning. 2026. "Understanding the Preferences of Genetic Tools and Extension Services for the Northern Australia Beef Industry" Animals 16, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010132

APA StyleMenchon, P., Cosby, A., Swain, D. L., & Manning, J. K. (2026). Understanding the Preferences of Genetic Tools and Extension Services for the Northern Australia Beef Industry. Animals, 16(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010132